Genesis: The Scientific Quest for Life's Origin (2005)

Chapter: Part IV The Emergence of Self-Replicating Systems -- 14 Wheels Within Wheels

Part IV

The Emergence of Self-Replicating Systems

Four billion years ago, life began to emerge on an Earth hellish almost beyond imagining. Volcanoes poured rivers of lava onto the land and belched noxious sulfurous vapors into the atmosphere, while meteors fell in a fitful bombardment. Violent weather and epic tides lashed the primordial coastlines. Nothing remotely lifelike graced the desolate surface.

Yet the seeds of life had been planted. The Archean Earth boasted vast repositories of serviceable organic molecules that had emerged from chemical reactions in the sunlit oceans and atmosphere, the depths of the crust, and the distant reaches of space. These molecules inevitably concentrated and assembled into vesicles, polymers, and other macromolecules of biological interest. Yet accumulations of organic macromolecules, no matter how highly selected and intricately organized, are not alive unless they also possess the ability to reproduce.

Most experts agree that life can be defined as a chemical phenomenon possessing three fundamental attributes: the ability to grow, the ability to reproduce, and the ability to evolve. The first of these three characteristics, individual cell growth, has occurred on an all but invisible scale for most of Earth’s history; for 3 billion years—from about 3.8 billion years ago to about 700 million years ago—the largest living organisms on Earth were microscopic single-celled objects. The third characteristic, evolution, proved to be slow and subtle: It took billions of years for cells to learn some of the most familiar biochemical tasks, such as using sunlight for energy or oxygen for respiration. But reproduction, life’s most dynamic overriding imperative, must have operated with an inexorable, geometric swiftness. In the geological blink of an eye, rapidly reproducing populations of cells doubled and redoubled, spreading through Earth’s oceans, colonizing and transforming the globe. Reproduction, more than any other characteristic of life, set the world of life apart from the prebiotic era.

For origin-of-life researchers, creating a self-replicating molecular system in a test tube has become the experimental Holy Grail. It has proved vastly more difficult to devise an experiment to study chemical self-replication than to simulate the earlier stages of life’s emergence—prebiotic synthesis of biomolecules, or the selective concentration and organization of those molecules into membranes and polymers, for example. In a reproducing chemical system, one small group of molecules must multiply again and again at the expense of other molecules, which serve as food. It’s an extraordinarily difficult chemical feat, but the rewards for success are immense. Imagine being the first scientist to create a lifelike chemical system in the laboratory!

14

Wheels Within Wheels

The origin of metabolism is the next great virgin territory which is waiting for experimental chemists to explore.

Freeman Dyson, Origins of Life, 1985

Scientists who study life’s origins divide into many camps. One group of researchers claims that life is a cosmic imperative that emerges anywhere in the universe if conditions are appropriate, while their rivals view life on Earth as a chance (and probably unique) event. One camp claims that some sort of enclosing membrane must have preceded life; another counters with models of “flat” surface life. Some researchers insist that life’s origin depended on solar energy, while others point to Earth’s internal heat as a more likely triggering source. Lacking adequate observational or experimental evidence to arbitrate these divergent views, positions sometimes become polarized and inflexible.

Perhaps the most fundamental of the scientific debates on origin events relates to the timing of two essential biological processes, metabolism and genetics. Metabolism is the ability to manufacture biomolecular structures from a source of energy (such as sunlight) and matter scavenged from the surroundings (usually in the form of small molecules). An organism can’t survive and grow without an adequate supply of energy and matter. Genetics, by contrast, deals with the transfer of biological information from one generation to the next—a blue-print for life via the mechanisms of information-rich polymers, such as DNA and RNA. An organism can’t reproduce without a reliable means to pass on its genetic information.

The problem as it relates to origins is that metabolism and genetics constitute two separate, chemically distinct systems in today’s cells,

much as your circulatory and nervous systems are physically distinct networks in your body. Nevertheless, just like your blood and your brains, metabolism and genetics are inextricably linked in modern life. DNA holds genetic instructions to make hundreds of molecules essential to metabolism, while metabolism provides both the energy and the basic building blocks to make DNA and other genetic materials. Like the dilemma of the chicken and the egg, it’s difficult to imagine a time when metabolism and genetics were not intertwined. Consequently, origin-of-life researchers engage in an intense ongoing debate about whether these two aspects of life arose simultaneously or independently and, if the latter, which one came first.

Most experts seem to agree that the simultaneous emergence of metabolism and genetics is unlikely. The chemical processes are just too different, and they rely on completely different sets of molecules. It’s much easier to imagine life arising one small step at a time, but what is the sequence of emergent steps?

Those who favor genetics as the first step argue in part on the basis of life’s incredible complexity. They point to the astonishing intricacy of even the simplest living cell. Without a genetic mechanism, there would be no way to ensure the faithful reproduction of all that complexity. Metabolism without genetics, they say, is nothing more than a bunch of overactive chemicals. Biologists, who must deal with complex cells and whose academic curriculum is dominated by the powerful, unifying spell of the genetic code, seem inclined to adopt this view without reservation.

Other scientists, myself included, tend to be more influenced by what we perceive as the underlying chemical simplicity of primitive metabolism. We are persuaded by the principle that life emerged through stages of increasing complexity. Metabolic chemistry, at its core, is vastly simpler than genetics, because it requires relatively few small molecules working in concert to duplicate themselves. Harold Morowitz and Günter Wächtershäuser, among others, agree that the core metabolic cycle—the citric acid cycle, which lies at the heart of every modern cell’s metabolic processes—survives as a chemical fossil almost from life’s beginning. This comparatively simple chemical cycle is an engine that can bootstrap all of life’s biochemistry, including the key molecules of genetics.

We conclude that if life arose through a sequence of ever more complex emergent steps, then bare-bones metabolism seems the more

likely precursor. Such a no-frills metabolic system, furthermore, might easily be enclosed in a primitive membrane of the type David Deamer makes in his lab. My sense is that many chemists, physicists, and geologists (not many of whom deal with DNA on a regular basis) are persuaded by this metabolism-first point of view.

Origin-of-life scientists aren’t shy about voicing their opinions on the metabolism-first versus genetics-first problem, which will probably remain one of the hottest controversies in the field for some time. Meanwhile, as this debate fuels animated discussions at conferences and in print, several groups of researchers are attempting to shed light on the issue by devising self-replicating chemical systems—metabolism in a test tube.

SELF-REPLICATING MOLECULES

The simplest imaginable self-replicating system consists of a single molecule that makes copies of itself. In the right chemical environment, such an isolated molecule will become two, then four, then eight molecules and so on in a geometrical expansion. Such a molecule is autocatalytic—that is, it acts as a template that attracts and assembles its own components from an appropriate chemical broth. Single self-replicating molecules are intrinsically complex in structure, but or-

Self-replicating molecules catalyze their own formation from smaller building blocks. In this example, one molecule AB plus individual A and B molecules combine to make new AB molecules.

ganic chemists have managed to devise several varieties of these curious beasts.

Self-replicating molecules possess a distinctive feature known as self-complementarity. Pairs of complementary molecules—molecules of different species that fit snugly together because of their shape and the arrangement of their chemical bonds—turn out to be relatively common in nature. Many of the proteins in your body, for example, function because they are complementary to food, neurotransmitters, toxins, or other molecules of biological importance. For this very reason, the synthesis of complementary molecules has become a central task of computer-aided drug design. If you can design a molecule that fits into pain receptors and thereby blocks pain signals, you can make a lot of money. Only a handful of known molecules are self-complementary, however, and even fewer can self-replicate.

Hungarian-born chemist Julius Rebek, Jr., now at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, has spent many years designing such molecules. In 1989 Rebek’s group employed three smaller molecules: the purine adenine; the two-ring cyclic molecule napthalene; and imide, a nitrogen-containing compound. When bonded end-to-end, the resulting adenine–napthalene–imide molecule is self-complementary and, if immersed in a solution containing lots of these three individual molecules, will make copies of itself.

Reza Ghadiri, leader of another productive research group at the Scripps Institute, focuses on yet another chemical system—self-replicating peptides, which are arguably much more relevant than most other molecules when it comes to the origin of life. Peptides, like proteins, are chainlike molecules built from long sequences of amino acids; their constituents are drawn from the same library of 20 amino acids that make up proteins, but they are typically dozens instead of hundreds of amino acids long. In 1996, Ghadiri’s group reported the first synthesis of a self-replicating peptide—a sequence of 32 amino acids. For self-replication to occur, however, this peptide had to be “fed” two reactive fragments, one of them 15 and the other 17 amino acids long. Given a steady supply of these two precursor fragments, new peptides formed spontaneously.

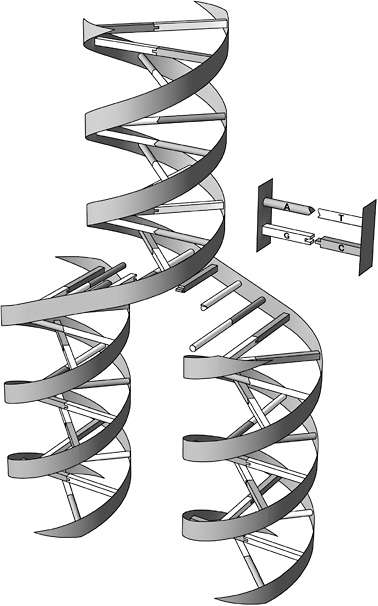

Self-complementary strands of the genetic molecule DNA display similar self-replicating behavior. As James Watson and Francis Crick famously discovered in 1953, the classic double-helix structure of the DNA molecule is like a long, twisted ladder, whose vertical supports

are chains of alternating phosphate and sugar molecules and whose rungs consist of the complementary pairs of molecules called bases: Cytosine (C) always pairs with guanine (G), while adenine (A) always pairs with thymine (T). Consequently, a single DNA strand with the base sequence ACGTTTCCA, say, is complementary to a second single

The double-helix structure of DNA features two complementary sequences of the bases A, C, G, and T. A always binds to T, while C always binds to G. The molecule replicates by splitting down the middle and adding new bases to each side. Thus, one strand becomes two.

strand TGCAAAGGT. When the two strands separate, each can then make a copy of the original double helix—as noted in one of the most celebrated and oft-quoted sentences in the history of biology, from Watson and Crick’s landmark paper: “It has not escaped our attention that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.”

The vast majority of DNA strands are not self-complementary, because the two halves of the double helix have different base sequences. But in 1986, German chemist Guenter von Kiedrowski and co-workers synthesized the first of the so-called “palindromic,” self-complementary DNA strands—the six-nucleotide sequence CCGCGG, which makes exact copies of itself if sufficient supplies of fresh C and G are provided.

It seems almost magical for a molecule to make copies of itself. Nevertheless, these self-replicating macromolecules do not meet the minimum requirements for life on at least two counts. First, such systems require a steady input of smaller highly specialized molecules—synthetic chemicals that must be supplied to the system from somewhere. Under no plausible natural environment could sufficient numbers of these component molecules have arisen independently. Furthermore—and this is a key point in distinguishing life from non-life—self-replicating molecules do not change and evolve, any more than a photocopy can evolve from an original.

SELF-REPLICATING MOLECULAR SYSTEMS

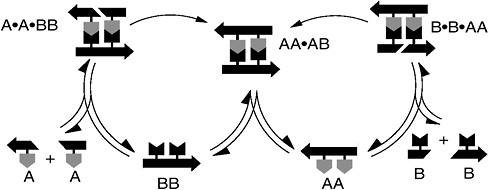

More relevant to metabolism are systems of two or more molecules that form a self-replicating cycle or network. Such systems are now the subject of intense research, and a variety of strategies for molecular self-replication have been identified. In the simplest so-called “cross-catalytic” system, two molecules (call them AA and BB) form from smaller feedstock molecules A and B. If AA catalyzes the formation of BB, and BB in turn catalyzes the formation of AA, then the system will sustain itself as long as researchers maintain a reliable supply of food molecules A and B.

It’s easy for theorists to elaborate on such a model. Rather than two cross-catalytic molecules, imagine a system with 10 or 20 molecules, each of which promotes the production of another species in the system. Santa Fe Institute theorist Stuart Kauffman points to such

In a cross-catalytic system, two different molecules (in this example designated AA and BB) catalyze the formation of each other. More complicated cross-catalytic systems with numerous molecules may have been the first self-replicating cycle on the early Earth.

“autocatalytic networks” as the most likely form of metabolic protolife, since that’s exactly what modern life does. Given the complexity of living cells, he proposes that the molecular repertoire of the first autocatalytic network might have to be expanded to as many as 20,000 different interacting molecular species. Accordingly, Kauffman drafts complex spaghetti-like illustrations of hypothetical reactants, each playing a key role in the integrated network.

Kauffman sees an important payoff in the behavior of such elaborate catalytic networks. Unlike a single self-replicating molecule, such vast networks of reactive molecules have the potential to increase in complexity and efficiency through numerous different interactions among molecules. The large number and variety of molecular interactions foster the emergence of new metabolic pathways and nested cycles of synthesis. Like a living metabolic cycle, Kauffman’s networks incorporate a certain degree of sloppiness. Through such variations, the system can change by shifting to new, more efficient reaction pathways and in the process display a defining trait of life—the ability to evolve.

THE GAME OF METABOLISM

Kauffman’s theory provides an intuitively appealing model for the emergence of primordial metabolic life. For one thing, if molecules in

a complex autocatalytic system efficiently catalyze each other, then there’s no need, at least at first, for a genetic mechanism. Accurate replication of the entire system is, in effect, intrinsic to the network. At the same time, the system has the potential to vary and gradually evolve. Growth, reproduction, evolution—the autocatalytic network would appear to meet the minimum criteria for life.

Kauffman’s model sounds good on paper, but there’s a dramatic gap between plausible theory and actual experiment. For example, what exactly is the chemical “A”? What is “B”? When asked, Kauffman shrugs and says, “That’s for the chemists to figure out.” And that’s what chemists have done.

If you want to make protolife in the lab, it’s best to start by designing a simple metabolic cycle. Metabolism is a special kind of cyclical chemical process with two essential inputs. First you need a source of energy—preferably chemical energy, since that’s what all known simple living cells use. (Photosynthetic cells use sunlight, to be sure, but these advanced organisms possess layers of chemical complexity far beyond those of more ancient, simple cells.) Second, you need reliable supplies of simple molecules, such as carbon dioxide and water, to provide the raw materials.

Living cells undergo chemical reactions not unlike burning, in which two chemicals (oxygen and some carbon-rich fuel) react and release energy. However, the objective in metabolism, unlike in an open fire, is to capture part of that released energy to make new useful molecules that reinforce the cycle. So metabolism requires a sequence of chemical reactions that work in concert.

Three basic rules govern this game of metabolism:

Rule 1—The Cycle: Describe a cycle consisting of a sequence of progressively larger molecules. The largest of these molecules should then be able to split into two smaller molecules, both of which are also in the cycle. In this way you end up with two sets of molecules, where before there was only one set and the cycle keeps on reproducing itself.

Rule 2—The Environment: Identify a plausible prebiotic environment that provides a reliable supply of raw materials (i.e., small molecules made up of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and other essential elements) and energy (preferably the chemical energy of unstable minerals). Furthermore, all of the different types of molecules in the cycle have to be able to survive in that environment long enough to keep the

cycle going. Extremes in temperature, pressure, or acidity, for example, may stabilize some kinds of molecules, while destroying others.

Rule 3—Continuity: An unbroken chemical history must link Earth’s earliest metabolic cycle with the metabolism of today’s cells. Deep within the metabolism of all of us, there are likely to be “fossil” biochemical pathways that point to life’s simpler beginnings. So any plausible model must conform to this “principle of continuity” and use molecules and energy sources that lie close to the basic metabolism of modern organisms.

Experimental evidence provides the ultimate test of any chemical theory. Each chemical step in a hypothetical metabolic cycle is a potential experiment, so you get bonus points if these crucial experiments work.

Three influential models exemplify the metabolism game at its best: the “Protenoid World” of Sidney Fox, the “Thioester World” of Christian de Duve, and a group of related hypotheses based on the reverse citric acid cycle, including the elaborate “Iron–Sulfur World” hypothesis of Günter Wächtershäuser.

THE PROTENOID WORLD

The granddaddy of all metabolism-first models emerged as the brain-child of protein chemist Sidney Fox, who began thinking about origin-of-life chemistry shortly after the publication of Stanley Miller’s 1953 paper. Fox’s career was strongly influenced by Thomas Hunt Morgan, a famed geneticist and a member of Fox’s Caltech thesis committee. “Fox,” Morgan would often remark, “all the important problems of life are problems of proteins.” Fox took this lesson to heart and began studying proteins’ role in life’s origin as a faculty member at Florida State University in the mid-1950s.

He imagined a hot primordial Earth where amino acids from the soup dried and baked on cooling volcanic rocks. He mimicked these conditions in his lab, drying amino acids on a hot surface at 170°C, and found that his chemicals quickly polymerized into a lumpy substance he called “protenoid.” This discovery, announced in 1958, would shape his checkered three-decade career in origins research.

Fox’s protenoids displayed fascinating behavior. They acted as catalysts, though to a rather modest degree compared to the modern pro-

tein catalysts that promote chemical reactions in every cell. When placed in hot water, they spontaneously turned into microbe-sized spheres, and sometimes these divided. He claimed that these spheres, though not as orderly as biological proteins, possessed a nonrandom structure with a permeable bilayer membrane. Increasingly, Fox suggested that the protenoids were “lifelike” and represented the key to life’s origins.

Fox and a small army of students carried out experiments to bolster his origin model. Solutions of protenoids were heated and cooled in a cycle that produced structures he called “microspheres”—cell-like entities that could absorb more protenoids, grow, and divide, thus forming a second generation of microspheres. These self-replicating objects, growing from nutrients in solution and lacking any genetic mechanism, formed the basis of a true metabolism-first model.

At first blush, the Protenoid World might seem to score well in the game of metabolism. Rule 1: The cycle is formed from widely available amino acids, which readily form protenoids that grow and divide. Rule 2: The environment, a volcanic setting near a tidal zone, is realistic for the early Earth. Rule 3: Protenoids seemed to conform to the principle of biological continuity, because closely related proteins are fundamental to modern life. What’s more, experiments seemed to support each step of the hypothesis.

For a time, Fox’s career thrived. Starting in 1960, he received generous grants from NASA’s Exobiology program, which supported a variety of research projects on the origin and evolution of life. Fox’s funds soon exceeded $1.5 million and allowed him to establish his own Institute of Molecular Evolution at the University of Miami in 1964. A steady stream of graduate students investigated protenoid properties.

As Sidney Fox increasingly fell in love with his Protenoid World model, his claims became more and more extreme. The origin-of-life problem had been solved, he said, and protenoids are “alive in some primitive way.” In his 1988 book, The Emergence of Life, he even made the bizarre and unsubstantiated claim that his protenoid microspheres possessed a kind of “rudimentary consciousness.”

As early as 1959, the mainstream origin-of-life community, led principally by Stanley Miller and Harold Urey, had begun distancing themselves from Fox’s claims. They resented what they regarded as the sensationalistic use of terms such as “protenoid” and “lifelike.” They scoffed at the idea that amino acids might have baked into anything

useful on a bed of lava. They questioned whether the protenoid structures were truly nonrandom in structure. The purported lifelike behaviors of microspheres were also challenged, especially the idea that they “replicated” in the biological sense. Equally strong was their objection that the Protenoid World scenario ignored the knotty problem of genetics. How would DNA and RNA have arisen in such a world?

Despite myriad objections to the theory, and the increasing scientific isolation of Fox, the Protenoid World was influential for at least two reasons. Not only did Fox develop the first comprehensive metabolism-first model, but he also championed the important philosophical position that origin processes might be nonrandom and deterministic—a view later embraced by numerous other origins workers. Nevertheless, by the late 1970s, Sidney Fox’s efforts had been marginalized, and they remained the target of jokes and derision until his death in 1998.

THE THIOESTER WORLD

The Belgian chemist Christian de Duve made his scientific name studying the structural and functional organization of cells—work that won him the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 1974. In an oft-repeated pattern, he then turned his attention to the origin of life, tackling the classic question from his perspective as a cell biologist. Not surprisingly, that background influences his origins theory.

De Duve takes a rather ambiguous stand in the metabolism- versus genetics-first controversy. For him, the simplest imaginable living thing is a cell-like entity that has a full complement of genetic material to control cellular functions. But he also recognizes the futility of jump-starting genetics without a well-established, elaborate arsenal of chemical reactions—what he calls “protometabolism” (as opposed to the more complex metabolism of modern cells). It’s really a question of where you place the boundary between nonliving and living systems. I’ve argued that the complex sequence of emergent events leading from geochemistry to life requires a rich taxonomy of intermediate states. De Duve appears to agree: His “Age of Chemistry” (protometabolism) precedes the “Age of Information” (genetics), which in turn precedes the “Age of the Protocell” (genetics and metabolism combined). Only then, with the merger of metabolism and genetics, does modern life truly emerge.

Let’s assume, de Duve says, that some early Earth environment (rather vaguely specified as a “volcanic setting” in his writings) was rich in hydrogen sulfide gas and iron sulfide minerals, along with the usual cast of carbon-based molecules. One chemical consequence of this sketchy scenario might be the production of sulfur-containing molecules called thioesters, which incorporate a strong bond between one sulfur atom and one carbon atom—a bond that can release a lot of energy if broken. De Duve’s hypothesis rests on the assumption that a steady supply of these energy-rich thioester molecules was available on the ancient Earth—hence the Thioester World.

Why focus on thioesters? For one thing, they are essential in the metabolism of modern cells. By breaking the strong carbon–sulfur bond, they can transfer energy to promote metabolic reactions, thus building larger molecules from smaller ones. In the Thioester World, a steady supply of thioesters provides the chemical energy required to drive protometabolism.

Of particular import, thioesters have a propensity to bond with amino acids, which would have been readily available in the prebiotic soup. Remarkably, when placed in solution, these amino acid–thioester groups spontaneously assemble into peptidelike chains (de Duve calls them “multimers,” because they differ in some chemical details from true peptides). At first, the multimers thus formed would have had little effect on the chemical mix. But, he speculates, eventually some of these big molecules by chance acquired catalytic properties (reminiscent of Fox’s protenoids). Gradually, as the environment became enriched in chemically active multimers, an autocatalytic cycle might have emerged, producing, he says, “protoenzymes required for protometabolism.”

The Thioester World hypothesis fits nicely with the primordial-soup paradigm favored by Miller and his allies. De Duve’s scenario relies on the environment to provide a steady input of various molecular building blocks, including amino acids, carbohydrates, and of course the essential energy-rich thioesters themselves. Such a model metabolism, in which the first cells eat and assemble components from their surroundings, is said to be heterotrophic (from the Greek, “other nourishment”). Heterotrophs must scavenge their molecules from the environment.

So how does de Duve’s Thioester World score in the game of metabolism? He certainly gets high marks for identifying a viable prebi-

otic environment rich in plausible simple molecules. Using thioesters as a reliable, renewable energy source is especially attractive, because it echoes the action of thioesters in modern biology. But he never specifies the molecules that comprise his metabolic cycle; the chemistry is vague. For de Duve, protometabolism is an awkward, transient, ill-defined phase that is necessary to set the stage for genetics. Thioesters promote the synthesis of catalytic multimers, which in turn promote the manufacture of a genetic molecule such as RNA. Only then does a well-defined biochemistry take root.

The bottom line: de Duve’s scenario is appealing in its broad outlines, but lacking in specific chemical details. And so, if you like details, there’s no better place to turn than Günter Wächtershäuser’s Iron–Sulfur World.