Genesis: The Scientific Quest for Life's Origin (2005)

Chapter: 5 Idiosyncrasies

5

Idiosyncrasies

The ability of the major atomic components of the cell to combine into molecules of considerable complexity … is enormous. However, the actual number of compounds that are used in biology is relatively small, comprising only hundreds of compounds.

Noam Lahav, Biogenesis, 1999

In a sense, you are what you eat. Nutrition labels on the side of every packaged food underscore this biochemical fact: Fats, carbohydrates, and proteins satisfy life’s energy requirements (i.e., calories) and provide life’s most basic molecular building blocks as well.

Carbon, the essential element of life, combines with other atoms in every living cell to form the molecules of life. Even as ancient rocks can entomb the original carbon isotopes from cells, so too, under the right circumstances, they can preserve larger fragments of life’s biomolecules. Such molecular remnants hold great promise for identifying ancient life, because terrestrial life is so remarkably, uniquely idiosyncratic in its choice of chemical building blocks.

SYNTHETIC QUIRKINESS

Consider the example of life’s hydrocarbons, the molecular family that includes waxes, soaps, oils, and all manner of fuels, from gasoline to Sterno. All cells require a rich variety of these molecules, which incorporate long, chainlike segments of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Hydrocarbons, which we eat in the form of fats and oils, serve many cellular functions, including the production of flexible cell membranes, efficient energy storage, varied internal support structures, and more.

In life and in commerce, long hydrocarbon molecules are usually made by linking smaller pieces end-to-end. When industrial chemists want to synthesize hydrocarbons, or when these molecules arise by natural nonbiological processes, the molecular chains are usually lengthened one carbon group at a time. This process ordinarily yields a suite of molecules with many different lengths, from just a few to many dozens of carbon atoms long, but all formed by the same stepwise mechanism.

Life builds hydrocarbons differently and in a strikingly idiosyncratic way. In each cell an amazing tool kit featuring half-a-dozen different protein catalysts, collectively called the “fatty acid synthase,” facilitates the assembly of hydrocarbon chains by adding units of three carbon atoms to a growing chain and then stripping one away. The net result is carbon addition by pairs. So life’s biochemistry is often characterized by a preponderance of hydrocarbon chains with an even number of carbon atoms: chains of 12, 14, or 16 carbon atoms occur in preference to 11, 13, or 15. As a result, given a suite of molecules from some unknown source and a mass spectrometer that can analyze the size distribution of those molecules, it’s not too difficult to tell whether the hydrocarbons came from living cells or from nonbiological processes.

Polycyclic compounds, an even more dramatic example of life’s molecular idiosyncrasies, include a diverse group of carbon-based molecules with several interlocking 5- and 6-member rings. A variety of cyclic molecules are found everywhere in our environment. Even before Earth was born, they were produced abundantly by chemical reactions in interstellar space and during star formation—processes that littered the cosmos and seeded the primitive Earth with cyclic organic molecules. The PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) found in the Martian meteorite ALH84001 are examples of these ubiquitous compounds. Cyclic molecules continue to be synthesized on Earth as an inescapable by-product of all sorts of burning: They are found in the soot of fireplaces and candles, the smoke of incinerators and forest fires, and the exhaust of diesel engines. Travel to the remotest places on Earth—the driest deserts of North Africa, deep ocean sediments, even Antarctic ice—and you’ll find PAHs.

Every living cell manufactures a variety of polycyclic carbon compounds but, as with hydrocarbon chains, the polycyclic compounds

produced by life are much less varied than those produced by inorganic processes. The 4-ring molecules called sterols, including cholesterol, steroids, and a host of other vital biomolecules, underscore this point. Literally hundreds of different 4-ring molecules are possible, yet while the relatively random processes of combustion or interstellar synthesis yield a complex mixture of cyclic compounds, life zeroes in almost exclusively on sterols and their by-products.

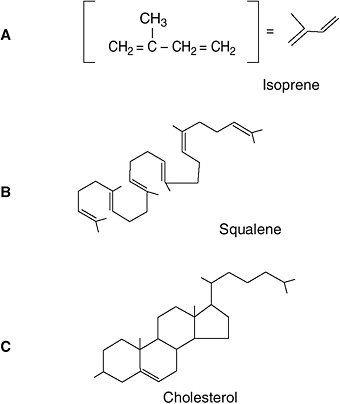

Again, cells employ a remarkably quirky synthesis pathway. The first step in forming a sterol is to manufacture lots of isoprene, a 5-carbon branching molecule (which the cell makes from three smaller molecules). Six isoprene molecules line up end-to-end to form

Cells manufacture polycyclic molecules in an idiosyncratic three-step process. First, three small molecules link together to form isoprene (A). Then six isoprene molecules line up end-to-end to make squalene (B). Finally, squalene folds up into the 4-ring cholesterol molecule (C). In these and subsequent drawings of molecules, each short line segment represents a chemical bond between two carbon atoms.

squalene, with 30 carbon atoms—24 of them in a chain, with six single carbon atoms branching off at regular intervals. This long molecule then folds up into the 4-ring sterol backbone.

Biochemical textbooks describe dozens of other examples of elaborate synthetic pathways: photosynthesis to make the sugar glucose, glycolysis (splitting glucose) to make the energy-rich molecule ATP (adenosine triphosphate), metabolism via the citric acid cycle, the production of urea, and countless other vital chemical processes. Over and over, we find that cells zero in on a few key molecules. DNA and RNA, which carry the genetic code, rely on ribose and deoxyribose alone, eschewing the dozens of other 5-carbon sugars. Proteins are constructed from only 20 of the hundreds of known amino acids. What’s more, sugars and amino acids often come in mirror-image pairs—so-called “right-handed” and “left-handed” variants—but life uses right-handed sugars and left-handed amino acids almost exclusively.

The take-home lesson is that life is exceedingly choosy about its chemistry. Of the millions of known organic molecules with up to a dozen carbon atoms, cells typically employ just a few hundred. This selectivity is perhaps the single most diagnostic characteristic of living versus nonliving systems. If an ancient rock is found to hold a diverse and nondescript suite of organic molecules, then there’s little we can conclude, yea or nay, about its biological origins. It may once have held life, or it may simply represent an abiotic accumulation of organic junk. If, on the other hand, an old rock holds a highly selective suite of carbon-based molecules—predominantly even-numbered hydrocarbon chains or left-handed amino acids, for example—then that’s strong evidence that life was involved.

A crucial requirement, if this logic is to be implemented in the search for life here or on other worlds, is that biomolecules must be stable over time spans of billions of years. Large protein molecules won’t last that long, and neither will the 20 amino acids that comprise the building blocks of proteins. Nor will most carbohydrates or hydrocarbon chains. Over time, water attacks the bonds of these biomolecules, breaking them into smaller fragments of no diagnostic use. But polycyclic compounds, like sterols, degrade more slowly and might survive over geological spans of time. Therein lies a possible top-down path to the discovery of life that is distant in space or time.

THE HOPANE STORY

Once in a very great while, extremely old rocks are found to hold microscopic droplets of a petroleum-like black residue—hydrocarbons that represent the remains of ancient marine algae. When such droplets were first discovered, decades ago, most scientists discounted the possibility that these organic remains were very old; no oil could survive billions of years of geological processing, they said. But subsequent discoveries and improved analytical techniques have convinced the geological community that a hardy breed of organic hydrocarbons can survive in ancient rock provided that temperatures never got too high.

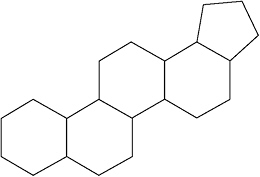

In their quest for life signs, a group of Australian scientists has focused upon what are perhaps the ideal biomarkers—distinctive sterol-derived polycyclic hydrocarbon molecules called hopanes. This group of elegant 5-ring molecules is known in nature only from the biochemical processes of cellular life, where it concentrates in protective cell membranes. Furthermore, different variants of hopanes point to specific groups of microbes with distinctive biochemical lifestyles. If an ancient rock happens to encase and preserve hopane-related molecular fragments with the diagnostic structures of once-living biomolecules, then we have convincing evidence of ancient life.

In 1999, a team of scientists led by Roger Summons (then at the Australian Geological Survey Organisation) presented compelling evidence for the survival of hopanes in a sequence of 2.7-billion-year-old

This 5-ring structure is characteristic of hopane, a distinctive biomolecule whose backbone may be preserved for billions of years in ancient sediments.

sedimentary rocks called the Pilbara Craton, in Western Australia. The black, carbon-rich shale layers in question came from a section of drill core extracted from a depth of about 700 meters. The mineralogy of the shale revealed that it had never experienced a temperature higher than about 300°C—an unusually benign history for such an ancient deposit.

Hopanes have been common biomolecules for a long time, so the Australian team’s principal challenge was ruling out contamination from more recent life. The rocks might have been contaminated hundreds of millions of years ago by subsurface microbes, or by groundwater carrying biomolecules from the surface, or perhaps even by oil, seeping from some other sedimentary horizon. Summons and his colleagues discounted the last of these possibilities because they found no trace of petroleum in adjacent sediment layers. Modern contamination from living cells, which abound in the lubricants that scientists use to drill their deep holes in the host rock, was also a concern. The team ruled out such contamination, too, because the suite of molecules preserved in the shale was “mature,” containing none of the fragile organic species that would point to recent lubricants and accompanying microbial activity.

Summons and his co-workers had to develop meticulous procedures to expose and clean unadulterated fresh rock surfaces: Break the rock, wash the surface, and measure the wash for contamination. They resorted to smaller and smaller rock fragments to avoid the inevitable impurities that had seeped in along cracks. Summons found that properly prepared powdered shale contained a distinct suite of ancient hydrocarbon molecules at hundreds of times higher concentrations than in adjacent chert and basalt layers from the same drill core. Nevertheless, the amount of hopanes was minuscule: of all the carbon-rich material extracted from the rock, no more than a precious few hundred parts per million were hopanes and related polycyclic molecules. Still, the very presence of hopanes provided evidence for ancient microbial life.

Having overcome daunting hurdles, Summons and his colleagues announced their finding in August 1999, in two remarkable papers, one in Science and the other in Nature. The Science article detailed extraction of hopanes from 2.7-billion-year-old shale—results that broke the previous record for the oldest molecular biomarker by about a billion years. The Nature article described the discovery of hopanes from

2.5-billion-year-old Australian black shale—a younger nearby formation, but with a twist. That formation included 2-methylhopanoid, a hopane variant known to occur in cyanobacteria, which are the primitive photosynthetic microbes responsible for generating Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere. The Australian team had found suggestive evidence that cyanobacteria were thriving long before 2 billion years ago, when Earth’s atmosphere is thought to have achieved modern levels of oxygen.

By extracting and identifying unambiguous biomarkers in ancient rocks, Summons and colleagues had made a major advance in detecting and characterizing ancient life. They also helped close the gap in our ignorance of life’s emergence by embellishing the top-down story and pushing it just a little bit further back in time.

BIOSIGNATURES AND ABIOSIGNATURES

The quest for unambiguous “biosignatures,” including hopanes and other distinctive molecules, represents an effective strategy in the search for ancient life on Earth and other worlds. However, the identification of “abiosignatures”—chemical evidence that life was never present in a particular environment—might also prove important in constraining models of life’s emergence.

Abiosignatures hold special significance to astrobiologists, who search for life in Martian meteorites and other exotic specimens. Are there physical or chemical tests that might preclude the presence of past life in those specimens? “NO LIFE ON MARS!” would be a bummer of a headline, but would nevertheless carry great scientific, not to mention philosophical, implications about the frequency of life’s emergence.

Hopanes not only represent biosignatures for ancient life on Earth, but they also point to a search strategy for other worlds, especially our nearest neighbor, Mars. Based on what we now know about life and its fossil preservation, we are unlikely to find unambiguous Martian fossils of single cells, much less animals or plants, at least not any time soon. A Mars sample return mission won’t happen for at least a dozen years, while human exploration of the red planet is many decades away. And even with such hands-on exploration, we’d be incredibly lucky to find a convincing fossil. We’re much more likely to find local concentrations of carbon-based molecules, from which we can determine the

carbon-isotopic composition. However, as the Greenland incident reveals, a simple isotopic ratio may not be sufficient to distinguish nonbiological chemical systems from those that were once living.

Suites of carbon-based molecules, if we can find them, hold much greater promise. An array of molecular fragments derived from a colony of cells, if not too degraded, will differ fundamentally from a geochemical suite synthesized in the absence of life. For now, molecules represent our best hope of finding proof of life both here and elsewhere in our solar system.

The ideal molecular biosignatures—and abiosignatures as well—must display three key characteristics. First, biosignatures should consist of distinctive molecules or their diagnostic fragments that are essential to cellular processes. Similarly, abiosignatures should consist of molecules that clearly point to nonbiological processes.

The second criterion is stability: biosignatures—and abiosignatures as well—must be molecules able to survive through geological time. Even the least altered ancient sediments have been subjected to billions of years of temperatures greater than the boiling point of water—conditions that significantly alter the chemical characteristics of any suite of organic molecules, whether biological or not. This criterion of stability, consequently, focuses our attention on unusually stable molecules.

Finally, the molecules must occur commonly and in reasonable abundance. A molecular biosignature or abiosignature is of no use unless it can be detected by mass spectrometry or other standard analytical techniques.

Hopanes, and the related sterols, are unquestionably excellent diagnostic biosignatures from the standpoint of stability, and they’re reasonably easy to analyze. Many ancient deposits yield traces of these molecules, and they will continue to be a tempting target for analysis, as well as a model for finding other biosignatures. But hopanes are probably not the ultimate answer in the search for signs of life: They seldom occur in abundance, and their absence cannot be taken as a reliable abiosignature.

An alternative to the search for reliable biosignatures and abiosignatures might be to identify diagnostic ratios of molecular fragments, akin to the carbon-12/carbon-13 isotopic ratio. However, we’re confronted with a vast multitude of possible molecule pairs. Which pair of molecules should we study?

My first foray into the search for biomarkers occurred in the summer of 2004. Preliminary studies by George Cody on organic compounds in meteorites prompted us to look at the ratio of two of the commonest PAHs: anthracene and phenanthrene. These 3-ring polycyclic molecules, both made up of 14 carbon atoms and 10 hydrogen atoms (C14H10), differ only in the arrangement of the rings: In anthracene the rings form a line, in phenanthrene a dogleg. We realized that the ratio of these two molecules might fulfill the essential biomarker requirements: Both are distinctive, relatively stable, common in the geological record, and easy to detect in trace amounts.

Phenanthrene and anthracene form in abundance through a variety of nonbiological processes, including any burning process that produces soot. These cyclic compounds are also synthesized in deep space, where they contribute to the molecular inventory of the carbon-rich meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites. The most celebrated of these is the Murchison meteorite, which fell to Earth in a cow field outside the small town of Murchison, about 100 miles north of Melbourne, Australia, on September 28, 1969. Meteorites hit Earth all the time, but the Murchison fall was special. For one thing, it was big—several kilograms of rock. For another, it was fresh and relatively un-

Phenathrene (top) and anthracene are 3-ring polycyclic molecules that differ only in their shape. The ratio of these two molecules differs in abiotic and biological systems.

contaminated—a number of pieces were collected while they were still warm. But, most important, the Murchison was a carbonaceous chondrite, containing more than 3 percent by weight of organic molecules. That black, resinous matter, formed billions of years ago in dense molecular clouds and protoplanetary disks, held a treasure trove of the molecules that could have accumulated on the prebiotic Earth.

George Cody had found that such meteorites often display about a 1:1 ratio of phenanthrene to anthracene. But biochemical processes seem to produce a different ratio. Many polycyclic biomolecules—including sterols and the varied hopanes—incorporate a 3-ring dogleg, so phenanthrene is a common and expected biomolecular fragment, and it should persist in rocks and soils, even when larger molecules break down. But for some reason, life almost never uses anthracene’s linear arrangement of three rings. Anthracene would thus seem to be correspondingly rare as a biomolecular fragment. Cody had found that biogenic coals typically hold 10 times more phenanthrene than anthracene.

Is the ratio of phenanthrene to anthracene a useful biomarker? Testing this idea required measuring the ratios of cyclic compounds in lots of samples, so that was the task I gave to Rachel Dunham, a bright and energetic undergraduate summer intern from Amherst College. Over the course of her 10-week stay in Washington, Rachel assembled dozens of natural and synthetic PAH-containing samples from around the world, analyzed them with our gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer, and managed to track down many more analyses from the vast coal and petroleum literature, since it turns out that PAHs are especially abundant in some fossil fuels.

The first few data points seemed to support the hypothesis. The Murchison and Allan Hills meteorites showed phenanthrene-to-anthracene ratios of 1.7:1 and 2:1, respectively. The biogenic Burgess Shale and a mature coal, on the other hand, yielded much higher ratios, close to 15:1. But then results began to scatter. Some low-grade coals had ratios less than 5:1, while the black, fossil-rich Enspel Shale was only about 2:1. The promising hypothesis began to crumble.

After several weeks of effort, and a thorough review of the published literature, Rachel discovered that we were simply reinventing the wheel. Coal experts have long known that anthracene is slightly less stable than phenanthrene. Consequently, “high-grade” coals that have experienced prolonged high temperatures and pressures have a

higher ratio of phenanthrene to anthracene, topping 20:1 in some specimens. Such a high ratio in any sample may have resulted from prolonged heating and have nothing at all to do with a biogenic past.

Our only useful conclusion was that unambiguously biological specimens never seem to display ratios less than about 2. So a lower ratio of phenanthrene to anthracene, as found in meteorites, synthetic-run products, and soot from burning carbon, may provide a valid abiomarker.

The next step? Perhaps we’ll try another PAH ratio, such as that of phenanthrene to pyrene, a particularly stable diamond-shaped molecule with four interlocking rings (C16H10). One thing is certain: we’ll never run out of molecules to try.

LOOKING FOR LIFE ON MARS

The most exciting, important, and potentially accessible field area to look for ancient alien life is Mars, which, like Earth, formed some 4.5 billion years ago. A mass of new data points to an abundance of surface water during the planet’s first billion years, dubbed the Noachian epoch by Mars geologists. Sunlit lakes, hydrothermal volcanic systems, and a benign temperature and atmosphere might have sparked life and made Mars habitable long before Earth. Perhaps fossils, molecular and otherwise, litter the surface.

The quest for Martian life has a checkered history. A century ago, American astronomer Percival Lowell reported observations of a network of canals on the red planet—evidence of an advanced civilization, he thought. Such speculation fueled the imaginations of science fiction writers, but hardened the scientific community to such unsubstantiated claims. NASA’s remarkable Viking Mars lander of the mid-1970s carried an array of experiments designed to find organic compounds and to detect cellular activity, but ambiguous results merely led to more controversy. Hot debates over purported fossils in the Allan Hills Martian meteorite represent just one more chapter in this contentious saga. Given such a troubled context, NASA will choose its next round of life detection experiments with the greatest of care.

Humans aren’t going to set foot on Mars anytime soon, but that’s what NASA’s amazing rovers are for. Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, and other robotic vehicles provide the experimental platform; they haul the instruments across the desolate Martian surface to probe tantaliz-

ing rocks and soils. The key to finding life (or the lack thereof) is to design and build a flight-worthy chemical analyzer for life. That has been the occupation of Andrew Steele throughout much of his career.

“Steelie,” my ebullient colleague at the Geophysical Laboratory, is a microbial ecologist who got his start studying the microbial corrosion of stainless steel in nuclear reactors. British Nuclear Fuels Ltd. sponsored his PhD thesis, which is still largely classified and unpublished. Radioactive isotopes often contaminate the thin outer layer of stainless steel that lines nuclear reactors—a difficult and costly cleanup problem. Steelie invented new microscopic techniques to study the steel surfaces, and he found that some microbes secrete biofilms that rapidly eat away steel, thus stripping off the affected layers and greatly simplifying decontamination. [Plate 4]

In 1996, just two weeks after defending his PhD thesis in England, the Allan Hills meteorite story broke. The timing was perfect, and Steelie was hooked. Setting his sights on nonradioactive ecosystems, he became obsessed with attempts to detect ancient life from the faint molecular traces in rocks. He contacted the NASA team, who were lacking in microbiology expertise and thus eager for his help. David McKay sent him a sample of the precious Martian rock, and within a year Steele had applied his microscopic techniques to investigations of the purported microbes. He made a memorable presentation at NASA’s annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston and landed himself a job as a NASA microbiologist working at the Johnson Space Center under McKay’s guidance.

Steelie’s assignment at NASA was to head the JSC Blue Team (consisting of Steele and a fellow gadfly), who were to try out every possible idea to disprove the hypothesis of Martian life in the Allan Hills meteorite. McKay led the significantly larger competing Red Team. McKay’s strategy of examining both sides of the issue was laudable and in the best tradition of scientific objectivity, but it may have backfired when Steelie did his job too well. He performed a series of high-resolution microscope studies and by 1998 had discovered that the Allan Hills specimen (like virtually every other meteorite he had ever examined) was riddled with contaminating Earth microbes. McKay was unconvinced and continued to promote his original interpretation of ALH84001. Discouraged at the cool reception accorded his findings, and missing his wife and family in England, Steele left his steady NASA employment in early 1999 for a hectic schedule of visiting professor-

ships and research jobs at the Universities of Montana, Oxford, and Portsmouth, along with more NASA consulting.

About the time that Andrew Steele’s research was making him something of a persona non grata at the Johnson Space Center, the Carnegie Institution’s Geophysical Laboratory found itself under new leadership. Wes Huntress, the former associate administrator of the NASA Office of Space Science (and the man who introduced the term “astrobiology” to the NASA community), had been hired to shake things up and expand Carnegie’s fledgling astrobiology effort. In a bold and welcome move, Huntress made Steele his first staff appointment in 2001. Steelie’s peripatetic scientific lifestyle seemed unsuited to the traditional academic world, but his unconventional background was just the ticket for the Geophysical Lab.

He arrived like a whirlwind, his shoulder-length blond hair and open tie-dyed lab coat flying behind him as he dashed between office and lab. Crates and boxes arrived by the dozen at his second-floor domain, two doors down from my own office. He crammed his lab space with DNA sequencers, chip writers and chip readers (benchtop machines that prepare and read slides), and a bewildering array of other microbiological hardware, most of which none of us geologists had ever seen before. A small army of bustling postdocs followed and the corridor took on new life. Chemist Mark Friese brought his collection of orchids to grace one alcove with a forest of exotic blooms. Molecular biologist Jake Maule maintained his pro-level golf game by challenging all comers to putting contests—a regular stream of golf balls began rolling past my open doorway.

In such an environment, new ideas fly thick and fast. Steelie had a master plan. He wanted to build a life-detecting machine to fly to Mars—a huge interdisciplinary project, given how much we still don’t know. On the scientific side, he had to figure out what constitutes a legitimate biosignature, so Steelie embarked on various paleontology projects, principally with German postdoc Jan Toporski, who happens to be his brother-in-law and soccer buddy. (There are also a lot of soccer balls and other soccer paraphernalia in the corridor.) They focused on a 25-million-year-old fossil lake in Enspel, Germany, where well-preserved fish, tadpoles, and other animals are found. Studies of their molecular preservation would provide important hints about life’s most stable and diagnostic molecular markers.

Then there was the detection part. It was essential to develop an

unambiguous procedure to find the tiniest amounts of any target molecule. That’s where Jake Maule came in. An aspiring astronaut trained in clinical medical technology, Jake’s job was to develop molecular antibodies—proteins with specialized shapes that would lock onto only one type of target molecule. [Plate 4]

Jake focused on producing hopane antibodies for use in a rapid and sensitive field test for microbes. His procedure involved injecting mice with hopanes and letting their immune systems do most of the work. Hopanes are too small to evoke an immune response by themselves, so Jake attached hopane molecules to a big protein called BSA (for bovine serum albumin). He injected 30 mice with a hopane–BSA solution, waited a week, and gave each a booster shot. In about three weeks, the mice manufactured a suite of hopane-sensitive antibodies. From each mouse, Jake extracted a syringe full of blood, which was centrifuged to separate out the red and white blood cells from the watery fluid that held the antibodies. Ultimately, each mouse yielded one tiny, precious droplet of that antibody-rich fluid.

Armed with hopane antibodies, Maule was ready to analyze ancient rocks, in an elegant four-step process.

Step 1: He crushed various promising rock samples and washed them in a solvent, which concentrated any hopane residues. Those solutions were loaded into the chip writer, a sleek benchtop machine about the size of a breadbox that placed an array of tiny dots of the solutions (some containing hopane and others not) and various standards onto a glass slide.

Step 2: With the chip writer, he applied a tiny amount of hopane antibody onto each of the sample spots, then rinsed. Some spots then retained hopanes with attached antibodies, while other spots were washed clean.

Step 3: He then treated each spot with another solution, this one containing a second antibody that locks onto any mouse antibody and is also highly fluorescent. All the spots with hopanes attached to mouse antibodies would thus fluoresce.

Step 4: Finally, he took the glass slide with its array of spots and put it into a second sleek machine, the chip reader, which, as its name suggests, recorded which spots fluoresced and which spots didn’t. Like microscopic lightbulbs, his antibodies glowed when hopanes were present in the rock sample.

Jake had devised a fast, automated process for identifying hopanes. But all that work and more was mere prelude to the most crucial aspect of a flight-ready analytical instrument—the design and engineering. Concepts and benchtop demonstrations were one thing, but an instrument on Mars has to be absolutely reliable, shock resistant, and very, very small. Steelie began dealing with nitty-gritty questions of how to collect a soil sample, how to introduce a small amount of sterile solvent to dissolve the target molecules, how to excite a fluorescent signal, and how to relay the information home to Earth, all in a tiny box. Soon, armed with a million dollars of NASA funding, he planned to fly the instrument on NASA’s 2013 mission to Mars.

Steelie’s baby is called MASSE—the Microarray Assay for Solar System Exploration. Adapting the latest in chip writer/chip reader technology, his team is building both flight-ready and handheld devices that use antibodies to detect trace amounts of dozens of diagnostic biomolecules: hopanes, sterols, DNA, amino acids, a variety of proteins, even rocket exhaust. Carnegie is not alone in developing such an instrument, and given the intense competition of other dedicated design teams, there’s no guarantee that MASSE will ever fly. Steelie is also competing against a seductive sample-return mission—a technically challenging effort to return a soda can-sized canister of Martian rock and soil to Earth on the same 2013 mission. Only one instrument package will be selected. Even if MASSE does fly, there’s no guarantee that it will arrive safely, and if it does arrive safely that it will find anything of interest. Of course, Steelie and his group are learning lots of fascinating stuff along the way. And I’ve never seen scientists have so much fun.

![]()

In our quest to understand life’s emergence, fossils provide essential clues. Even lacking morphological evidence, fossil elements, isotopes, and molecules point to the nature of primitive biochemical processes. These microscopic remains also reveal a diversity of life-supporting environments and help to constrain the timing of life’s genesis. What’s more, if we’re lucky, fossils from Mars or some other extraterrestrial body may eventually provide the best evidence that life has emerged more than once in the universe.

And yet, valuable as these insights may be, all known fossils represent remains of advanced cellular organisms similar to those alive today. Few, if any, clues remain regarding the emergent biochemical steps that must have preceded cells. To understand how life arose, therefore, we must go back to the beginning and approach the question of origins from the bottom up.