Genesis: The Scientific Quest for Life's Origin (2005)

Chapter: Notes

Notes

PREFACE

p. xiii It is possible: A significant literature explores the contrasting views of life as a chance event (Monod 1971) versus a cosmic imperative (de Duve 1995a, Morowitz 2002).

p. xvi James Trefil: Hazen and Trefil (1991), Trefil and Hazen (1992).

p. xvii “the unfolding of life …”: Morowitz (2002, p. 84).

p. xvii conference in Modena, Italy: The “Workshop on Life” was held September 3–8, 2000, as one of the satellite meetings before the Millennial World Meeting of University Professors in Rome, September 8–10. The conference proceedings are collected in Pályi et al. (2002).

PROLOGUE

p. 1 This idea had received a boost: Corliss et al. (1979, 1981). See Chapter 7 for more details on Jack Corliss’s controversial claims.

p. 2 Morowitz’s dense tabulation: The table of water’s dielectric constant as a function of temperature and pressure came from Tödheide (1972, Table XI, p. 492). See also Uematsu and Franck (1981), Franck (1987), Shaw et al. (1991), and Franck and Weingartner (1999) for subsequent measurements by the same group at the Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, University of Karlsruhe. In spite of our surprise at seeing these results, experts in petroleum chemistry had long known about water’s distinctive changes in properties at elevated temperature and pressure (e.g., Simoneit 1995). Theorist Everett Shock had incorporated these effects into his calculations of hydrothermal reactions relevant to prebiotic chemistry

(Shock 1990a, 1990b, 1992a, 1993; Shock et al. 1995). Nevertheless, few researchers in the origin-of-life community had made this connection, and no relevant experiments had been performed at high temperature and pressure.

p. 2 detailed chemical scenario: Wächtershäuser (1988a, 1990a, 1992). His work is reviewed in Chapters 8 and 15.

p. 3 His name provided: A perspective on Harold Morowitz’s contributions to the founding of astrobiology is provided by Dick and Strick (2004, pp. 61-65).

p. 4 Hat’s pressure lab: The apparatus and its operation is described in Yoder (1950).

p. 8 “Humpane”: Jack Szostak writes, “It’s the normal result to obtain a mess of hundreds of compounds. The central problem of prebiotic chemistry is how to avoid the universal tar of organic chemistry, and channel the chemistry into the products needed for the origin of life.” [Jack Szostak to RMH, 21 August 2004]

1

THE MISSING LAW

p. 11 “It is unlikely …”: J. H. Holland (1998, p. 3).

p. 11 Two great laws: Von Baeyer (1998) provides a history of the laws of thermodynamics.

p. 12 The discovery of a dozen: For a review of the principal laws of nature and their discovery, see Hazen and Trefil (1991).

p. 12 scholars of the late nineteenth century: The history of the idea that science has learned everything of significance appears in Horgan (1996), who defends and amplifies the idiotic claim.

p. 12 Ilya Prigogine: Prigogine’s influential analyses of emergent systems, which he called “dissipative systems,” appears in his books Order Out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature (Prigogine 1984) and Exploring Complexity: An Introduction (Nicolis and Prigogine 1989). Of special interest to Prigogine were patterns that arise spontaneously in a shallow pan of boiling water (Bénard cells) and in certain types of slowly reacting chemicals (Belousov–Zhabotinski, or B–Z, systems). These systems, which could be analyzed with mathematical rigor, are representative of a larger class of phenomena in which energy flows through a collection of interacting particles. In the words of Wicken (1987, p. 5), “dissipation through structuring is an evolutionary first principle.”

p. 13 complex, turbulent convection: The peculiar behavior of boiling water is addressed, for example, in Nicolis and Prigogine (1989, pp. 8-15).

p. 14 patterns in water and sand: An extensive technical literature analyzes the formation of sand patterning. Of special note are the classic works of Ralph Bagnold (1941, 1988).

p. 14 understanding such simple systems: Several reviewers question the idea that studies of patterning in simple mechanical systems such as sand can elucidate the behavior of much more complex biological systems. Graham Cairns-Smith writes: “I think that your discussion of emergent systems could do with a more explicit reference to the two main ways in which interestingly complex systems arise in biology—development and evolution. Development is modeled by, say, the Mandelbrot set: an amazing infinitely complex product with a childishly simple specification. And incidentally I don’t see any new physical law here, just mathematics.” (G. Cairns-Smith to RMH, 31 August 2004).

Jack Szostak echoes this opinion: “Part of the problem is the lack of a clear definition or understanding of what we mean by emergent phenomena, which leads to people referring to distinct things with the same term. So, in one sense, phenomena such as vortices or sand ripples are ‘emergent’ since they are collective phenomena not exhibited by the individual components of the system. On the other hand, there seem to be different kinds of phenomena one could also call ‘emergent’…. Darwinian evolution emerges from the combination of replicating informational polymers and compartmentalization.” [Jack Szostak to RMH, 21 August 2004] In other words, some scientists argue that emergent systems that become complex through a competitive selection process are fundamentally different from those that obey simple rules of interaction.

I’m more inclined to think that all emergent systems, whether shifting sand dunes or biological evolution, may ultimately be modeled based on a small set of “selection rules” reducible to mathematical statements. Ultimately, evolution through competitive selection represents simply another (though admittedly more elaborate) way that systems tend toward the most efficient way to dissipate energy.

p. 15 A small band of scientists: The Santa Fe Institute and its studies in emergence are discussed in Waldrop (1992) and Regis (2003).

p. 15 John Holland: Holland’s influential works include Hidden Order (J. H. Holland 1995) and Emergence: From Chaos to Order (J. H. Holland 1998).

p. 15 BOIDS: This program is available at www.red3d.com/cwr/boids. The program tracks the flocking behavior of a hundred or so “BOIDS,” each of which moves according to three rules: separation to avoid crowding flockmates, alignment to follow the flock’s average direction, and cohesion to steer toward the average position of flockmates.

p. 15 Physicist Stephen Wolfram: Wolfram (2002).

p. 16 Danish physicist Per Bak: Bak’s most accessible writings are found in his popular book, How Nature Works: The Science of Self-Organized Criticality (Bak 1996).

p. 16 Santa Fe theorist Stuart Kauffman: Kauffman (1993).

p. 16 Nobel Laureate Murray Gell-Mann: Gell-Mann and Tsallis (2004). Ideas of non-extensive entropy and related definitions of complexity are provided by Lopez-Ruiz et al. (1995), Shiner et al. (1999), Gell-Mann and Lloyd (2004), Latora and Marchiori (2004), Plastino et al. (2004). See also Gell-Mann (1994, 1995).

p. 17 fossil-rich hundred-foot-tall cliffs: The Miocene formations of Calvert County, Maryland, have been a Mecca for fossil collectors for two centuries. Details of the geology and paleontology are recorded in W. B. Clark (1904).

p. 17 Factor 1: The relationship between concentration of agents and complexity has the qualitative form of the so-called error function. This function begins at zero complexity for low concentrations of agents. As the

p. 17 The relationship between the concentration of interacting agents in a system (N) and the complexity of the system (C) has the qualitative form of the error function. At low N, no emergent structures arise, but as N increases, so does C, to an upper limit.

concentration rises, it reaches some critical value, and complexity begins to rise. Eventually, at a higher concentration of agents, the system’s complexity achieves a maximum value.

p. 19 One ant species: Camazine et al. (2001, pp. 256-283). [Also E. O. Wilson to RMH, 9 April 2004; B. Fisher to RMH, 5 May 2004; C. W. Rettenmeyer to RMH, 12 May 2004]

p. 19 Studies of termite colonies: Solé and Goodwin (2000, p. 151).

p. 19 spiral arm structure: The formation of spiral arms requires “a central mass and a velocity large enough to produce a significant shear…. You also need time for the patterns to be established. The low mass objects don’t survive long enough.” [Vera Rubin to RMH, 7 April 2004]

p. 19 Factor 2: I suspect that one of the principal difficulties in quantifying emergent complexity is related to the varied ways that agents may be interconnected. The shifting interactions by immediate contacts of adjacent sand grains are not easily equated to the persistent chemical markers of moving ants or the elaborate networks of variable impulses that connect neurons. Nor are any of these examples exactly analogous to the interactions of molecules necessary for the origin of life.

p. 19 A rounded grain: Bagnold (1941, p. 85).

p. 20 The conscious brain: See, for example, Johnson (2001).

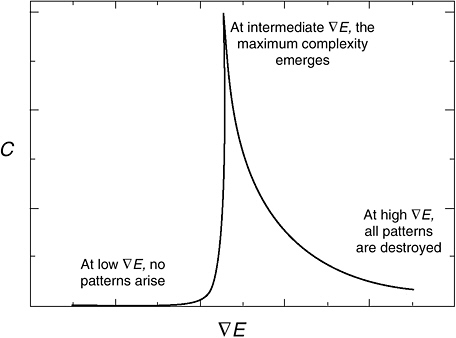

p. 20 Factor 3: The relationship between energy flow and complexity bears a qualitative similarity to a bell-shaped curve. At low energy flux, no patterning occurs and the complexity is zero. At some minimum energy flux, pattern formation begins and complexity quickly achieves a maximum value. Above a critical value, however, the energy flux is too great and the emergent patterns begin to disperse.

p. 20 no pattern can emerge: Physicist Paul C. W. Davies examines this issue from the standpoint of gravity, which is the initial and ultimate source of ordering in the universe (Davies 1999, p. 64).

p. 21 Factor 4: Cycling may be important in origin-of-life scenarios, but the imposition of any kind of cycle adds at least two new variables to an experiment. In the case of a temperature cycle, for example, one must select the duration of the cycle (typically on the order of minutes to days) and the two end-point temperatures. It may also be desirable to control the rate of temperature change (gradual versus abrupt), which adds additional variables. Needless to say, such added variables complicate an experiment and its interpretation.

p. 22 amazing stone circles: Kessler and Werner (2003).

p. 22 ∇E(t): This expression indicates both the flow of energy through the system, ∇E, and the cycling of that energy, which is a function of time, t.

p. 20 The relationship between the energy flowing through a system of interacting agents (∇E) and the complexity of the system (C) has the form of a critical curve. At low ∇E, no emergent structures arise, but as ∇E increases above a critical value, structure rapidly appears and C increases. At high ∇E, however, patterns are destroyed.

2

WHAT IS LIFE?

p. 25 “I know it when I see it.”: Associate Justice Potter Stewart of the U.S. Supreme Court made this statement as part of his concurring opinion in the 6-3 ruling that overturned the ban on pornographic films, June 22, 1964: “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material … but I know it when I see it.”

p. 25 A recent origin-of-life text: Lahav (1999, pp. 117-121).

p. 25 “What is life?”: Pályi et al. (2002).

p. 26 “top-down” approach: Jack Szostak states “I don’t think the earliest fossils tell us anything about life’s earliest chemistry. These fossils are all quite sophisticated organisms.” [Jack Szostak to RMH, 21 August 2004] Gustaf Arrhenius echoes this view: “The most ‘primitive’ organisms that we can lay our hands on are already hopelessly sophisticated biochemically; they are more like us than anything original.” [Gustaf Arrhenius to RMH, 23 December 2004]

Indeed, a principal discovery of Precambrian paleontology is that modern-type cells have populated Earth for at least 80 percent of its history. The window for life’s emergence is correspondingly brief.

p. 27 “working definition”: See Joyce (1994).

p. 28 thin molecular coating: The idea of “flat life” has been explored by Wächtershäuser (1988a, 1992) among others. For more details see Chapter 15.

p. 28 Claude Lévi-Strauss: Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology, argued that all humans share similar patterns of thought. His analysis of myths from various cultures, for example, stresses the common reliance on dichotomies in dealing with our role in the cosmos. See Lévi-Strauss (1969, 1978).

p. 28 neptunists, … plutonists: This debate, as well as that between catastrophists and uniformitarianists, was fueled by a conflict between scientific and religious interpretation of natural history. See, for example, Rudwick (1976) and Laudan (1987).

p. 29 “The unfolding of life …”: Morowitz (2002, p. 84). Several other authors, notably Christian de Duve (1995a), have adopted a similar framework of sequential episodes in life’s emergence. See also Davies (1999), Maynard-Smith and Szathmáry (1999), and Bada (2004).

p. 30 semantic question: For a fuller explanation of these ideas, see Hazen (2002). Jack Szostak writes: “I used to think of the transition from non-life to life as a discontinuous event marked by the sudden start-up of Darwinian evolution. But as I’ve started to work on more aspects of the problem and look at it in more detail, what I see is more of a series of smaller steps.” [Jack Szostak to RMH, 7 September 2004]

p. 30 philosopher Carol Cleland: Cleland and Chyba (2002).

p. 31 Saturn’s recently visited moon: Evidence for volatiles at Titan’s surface are presented by Lunine et al. (1999), Campbell et al. (2003), Griffith et al. (2003), and Lorenz et al. (2003). For the latest results from the Huygen’s probe, see: http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/home/index.cfm.

3

LOOKING FOR LIFE

p. 33 “Scientists turn reckless …”: Lightman (1993, p. 41).

p. 33 meteorite from Mars: For an overview of Martian meteorites and their identification see McSween (1994). Goldsmith (1997) provides a popular account of the Allan Hills controversy.

p. 33 Theorists maintained: Calculations by Jay Melosh and co-workers of Caltech (Melosh 1988, 1993; Head et al. 2002) reveal that, although a lot of material is vaporized in large planetary impacts, rocks at the periphery of

the impact site may be hurled unscathed off the surface into space. Such a process is thought to have transferred material from Mars to Earth. Similar impacts on Earth have certainly blasted terrestrial rocks into space, though the transfer of Earth rocks to Mars is much more difficult because of two gravitational impediments: Mars is much farther from the Sun, and it has a smaller gravitational field.

An alternative intriguing hypothesis is that cellular life may have arisen very early in Earth’s history, and that some of these microbes may have been blasted into space by large asteroid impacts. Even if a subsequent globe-sterilizing giant impact occurred, life could have been reseeded by an Earth meteorite.

p. 33 Allan Hills region of Antarctica: The ice deserts of Antarctica are ideal hunting grounds for meteorites. These clean, dry regions persist for thousands of years, and dark-colored meteorites stand out starkly against their white surface. Scientists in helicopters or on snowmobiles can collect dozens of pristine specimens in a short field season. These areas are also valuable because they provide a relatively unbiased inventory of meteorite types. In more temperate regions, stony meteorites often blend into the surrounding rocky landscape, where they just weather away; only the resistant iron meteorites stand out, so they have always constituted the majority of meteorite finds. Antarctic collecting areas reveal that stony meteorites are much more common. For an informative visual overview, see the Web site of ANSMET, the Antarctic Search for Meteorites program, cosponsored by NASA and the Smithsonian Institution: http://geology.cwru.edu/~ansmet/.

p. 34 A team of biologists: D. S. McKay et al. (1996).

p. 34 On August 7, 1996: Dick and Strick (2004, pp. 179-201) provide a detailed history of this incident. The timing of the prepublication press conference was unusual because Science nearly always holds up press announcements until the afternoon before an article’s publication date (in this case, Friday, August 16). However, the important story leaked more than a week before publication because, according to Goldsmith (1997), a top official in the Clinton administration told a prostitute, who, in turn, sold the information to a tabloid. Science, in agreement with the authors and NASA, therefore made the article available on their Web site eight days before print publication. [R. Brooks Hanson to RMH, 15 April 2004]

p. 35 “Although there are alternative …”: In subsequent years, team leader David McKay elaborated on this argument by attempting to calculate the degree to which several weak lines of evidence coalesce to produce a strong probability when taken together. See, for example, D. S. McKay et al. (2002).

p. 36 aggressively challenged: Science received dozens of letters to the editor and technical comments challenging aspects of the D. S. McKay et al.

(1996) paper. Of these submissions, three letters were published in the September 20, 1996, issue and a technical comment appeared in the December 20, 1996, issue.

p. 36 Point number one: The most abundant organic molecules in the Allan Hills meteorite are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or PAHs, which are a ubiquitous component of carbon-rich meteorites as well as of soot, diesel exhaust, and myriad industrial processes. See, for example, Allamandola et al. (1985, 1989).

p. 36 Point two: An extensive and often contradictory literature has arisen around the question of Allan Hills’ carbonate origins, particularly the temperature of their formation. See, for example, Harvey and McSween (1996) and Scott et al. (1997).

p. 36 Skeptical experts: The distinctive magnetite crystals, which possess a purity, crystal form, magnetic structure, and chainlike distribution characteristic of Earth microbes, provide the greatest remaining hope for proponents of the Martian life hypothesis. No plausible nonbiological explanation for these features has yet been proposed.

p. 36 purported fossil microbes are too small: Morowitz (1996). See also Schopf (1999, pp. 317-320).

p. 36 The story became even more confused: Steele et al. (2000a, 2000b).

p. 37 J. William Schopf: Schopf (1999, pp. 304-325).

p. 37 “I was like Daniel …”: Schopf (1999, p. 309).

p. 37 “The minerals can’t prove it …”: Schopf (1999, p. 316).

p. 37 “There are fine lines …”: Schopf (1999, p. 325).

p. 38 Such catastrophic events: Maher and Stevenson (1988), Sleep et al. (1989). Estimates of the rate and magnitude of large impacts come largely from statistical studies of the sizes and ages of lunar craters.

p. 38 We don’t know: Jack Szostak notes that “some people now think that a Hadean origin is likely, and that totally sterilizing impacts may have ended earlier than previously thought. And even following a sterilizing event, cells blasted into space might have reseeded the Earth.” [Jack Szostak to RMH, 21 August 2004]

p. 38 oldest known fossilized penis: The original report was Siveter et al. (2003). The story appeared in USA Today on December 12, 2003. There was much scientific interest in this discovery because highly varied penile appendages constitute the basis for classifying the group of crustaceans called copepods.

p. 39 Apex Chert: Schopf (1993). Apex Chert fossils had been reported earlier, for example in Awramik et al. (1983) and in Schopf and Packer (1987). The 1993 paper was the first to enumerate 11 species of ancient Apex microbes.

Bruce Runnegar writes, “Although it is more dramatic to highlight the 1993 announcement of Schopf’s discovery of Earth’s oldest fossils, one should be aware that the same kind of announcement came out of the Schopf lab in the late 1970s from rocks of about the same age in the North Pole area of Western Australia. These were discovered by Stan Awramik at UC Santa Barbara and some people still believe these are the ‘best of the oldest.’ However, there are problems with these as well.” [B. Runnegar to RMH, 4 March 2005]

p. 39 world’s leading experts: Among Schopf’s most noted works is the volume he edited on Precambrian paleontology, Earth’s Earliest Biosphere: Its Origin and Evolution (Schopf 1983). In that work he presents his own review of the earliest known microbes (Schopf and Walter 1983).

p. 39 UCLA protocol: Schopf (1999, pp. 71-100).

p. 40 Bonnie Packer: [James Strick to RMH, 1 September 2004] The initial publication was Schopf and Packer (1987). Packer was the first person to observe unusual microstructures in Apex Chert samples.

p. 40 Controversy erupted: Brasier et al. (2002). An account of the controversy is presented by Knoll (2003, pp. 60-65).

p. 41 Further study: The geology of the Apex Chert site is still a matter of considerable debate. Brasier and Australian geologist John Lindsey highlighted these concerns at subsequent seminars, including a joint presentation at the Carnegie Institution’s Geophysical Laboratory on July 1, 2002. For opposing viewpoints see Lindsay et al. (2003a, 2003b), Brasier et al. (2004), and Schopf et al. (2002).

p. 41 “We reinterpret …”: Brasier et al. (2002, p. 77).

p. 41 a rebuttal: Schopf et al. (2002).

p. 42 “News and Views”: Gee (2002). See also Dalton (2002).

p. 42 This debate: The Astrobiology Science Conference 2002 (the second such meeting) took place from April 7 to April 11 at NASA Ames Research Center. Abstracts of the meeting are available at http://web99.arc.nasa.gov/abscon2.

p. 42 Schopf spoke: The original NASA videotape of this debate was provided by Lynn Rothschild of the NASA Ames Research Center. A description of the session, including a photograph of Schopf peering at Brasier, appears in Dalton (2002).

p. 42 soften his assertion: While Schopf did back off his claim of fossil cyanobacteria in the lecture, he repeated the arguments in a later article, claiming that “Several of the Apex species seem almost indistinguishable from living cyanobacteria.” (Schopf 2002, p. 173).

p. 43 Raman spectroscopic data: see also Pasteris and Wopenka (2003).

p. 44 equally difficult to disprove: Scientists are taught to evaluate

alternative hypotheses based on Occam’s razor: Accept the hypothesis that requires the fewest assumptions. But how does one choose between evidence for and against the existence of ancient microbial life, or life in a Martian meteorite, for that matter? If your philosophical bias is that life emerges rapidly and is thus ubiquitous in the universe, then any tantalizing sign of life—carbon smudges or scrappy fossils—will provide encouraging supporting evidence. If you think life rare or unique, then the tenuous character of the same data will prevail. Consequently, to prove either case—that an ancient rock does or does not hold evidence for life—is extraordinarily difficult. Brasier et al. were successful in casting doubt on Schopf’s claims of microbial fossils, but they came nowhere close to disproving that the carbon residues were biogenic in origin.

p. 44 Meanwhile, paleontologists: Claims of 3.5-billion-year-old microfossils from South Africa were published by Furnes et al. (2004).

4

EARTH’S SMALLEST FOSSILS

p. 47 “Millions of brutal years …”: Simpson (2003, p. 72).

p. 48 Andrew Knoll: The “Origin of Life” Gordon Research Conference took place from July 27 to 31, 1997. Two of Knoll’s reviews (Knoll 1996, 2003) provide accessible overviews of Earth’s earliest fossil cells.

p. 50 severe analytical challenge: Simultaneously with our efforts, Derek Briggs and co-workers at the University of Bristol produced similar electron microprobe maps of fossils (Orr et al. 1998).

p. 51 Rhynie, Scotland: The fossils of the Rhynie Chert are documented in the classic studies of Kidston and Lang (1917-1921).

p. 51 Kevin Boyce: Boyce’s analytical work on Devonian plant fossils is described in Boyce et al. (2001, 2003).

p. 54 Analytical studies: Schidlowski et al. (1983), Schidlowski (1988).

p. 54 mammoth bones: Koch (1998).

p. 54 fossil coal: McRae et al. (1999).

p. 54 Burgess Shale: Butterfield (1990) reports bulk isotopic values of approximately −27 for the Burgess Shale. The classic 525-million-year-old Burgess Shale deposits of British Columbia preserve a diverse soft-bodied fauna in exquisite detail. These fossil forms are vividly described in Gould (1989).

p. 55 Values as low as −50: The distribution of ancient carbon isotope values has been tabulated, for example, by Schidlowski et al. (1983) and H. D. Holland (1997).

p. 55 Walter’s work: See, for example, Walter et al. (1972), Walter (1976, 1983).

p. 55 “It’s Strelley Pool Chert …”: The age and geological setting of the Strelley Pool Chert has been described by C. P. Marshall et al. (2004) and Allwood et al. (2004).

p. 59 Earth’s Oldest “Fossils”?: Bruce Runnegar writes, “I would prefer to title this section “Earth’s Oldest Life” …. Fossils have been reported, even named (Isuasphaera), from the Isua rocks by Hans-Dieter Pflug but no one accepts them as remains of living organisms. What is being discussed here is only, at best, ‘isotopic fossils.’” [B. Runnegar to RMH, 4 March 2005]

p. 59 oldest known rocks: Moorbath et al. (1986), Nutman et al. (1996, 1997).

p. 59 Stephen J. Mojzsis: Mojzsis et al. (1994, 1996). See also E. K. Wilson (1996) and H. D. Holland (1997) for analyses of the report.

Bruce Runnegar writes, “This is a dramatic way to present the discovery, but light carbon had been reported from the Isua rocks since the 1960s, I believe. Manfred Schidlowski, in particular, published many articles arguing that Isua provided evidence for life on Earth prior to the Mojzsis et al. article in Nature.” [B. Runnegar to RMH, 4 March 2005]

p. 59 Akilia rocks posed problems: Fedo and Whitehouse (2002). See also Whitehouse (2000), Lepland et al. (2005). Kerr (2002a), Simpson (2003), and Dick and Strick (2004) provide analyses of the controversy. Aivo Lepland of the Geological Survey of Norway, who spent five years attempting to duplicate Mojzsis’s results without success, has raised additional questions about the validity of the results. As a consequence, Gustaf Arrhenius, a coauthor on the 1996 paper, has distanced himself from the original conclusions (Lepland et al. 2005). “I think there must have been a mix-up of the samples,” he says (Dalton 2004, p. 688).

More convincing evidence for ancient biogenic carbon is provided by Rosing (1999), who reported negative carbon isotope values from 3.7-billion-year-old sediments from the Isua region of Greenland. [Gustaf Arrhenius to RMH, 8 August 2004]

p. 60 plausible explanations: See, for example, van Zuilen et al. (2002). Negative carbon isotope fractionation is known to occur inorganically, for example, at high temperature, when iron carbonate breaks down to graphite plus iron oxide.

5

IDIOSYNCRASIES

p. 61 “The ability of …”: Lahav (1999, p. 64).

p. 62 industrial chemists: The standard industrial process for synthesizing chainlike carbon molecules is called Fisher–Tropsch synthesis.

p. 62 Life builds hydrocarbons: The biochemical process for synthesizing chainlike molecules is detailed in Lehninger et al. (1993, pp. 642-649).

p. 62 produced abundantly: Allamandola et al. (1985, 1989, 1997), Allamandola and Hudgins (2003). PAHs are identified by their distinctive infrared emission spectra.

p. 63 4-ring molecules called sterols: Lehninger et al. (1993, pp. 669-674).

p. 64 A crucial requirement: For a survey of molecular biomarkers see K. E. Peters and Moldowan (1993).

p. 65 The Hopane Story: Hopanes were discovered by Guy Ourisson of the Université Louis Pasteur and co-workers (Rohmer et al. 1979, Ourisson and Albrecht 1992, Ourisson and Rohmer 1992, Tritz et al. 1999). The identification of hopane-related compounds in ancient Australian rocks is reported by Summons et al. (1999), with a commentary by Knoll (1999). For related work on ancient biomolecules from Australian rocks, see Summons and Walter (1990), Summons et al. (1996), and Buick et al. (1998).

p. 65 In 1999: Brocks et al. (1999).

p. 67 2-methylhopanoid: Bruce Runnegar writes, “As all extant cyanobacteria, so far as is known, make 2α-methylhopanes, the time of origin of this innovation may significantly predate the origin of the last common ancestor of living cyanobacteria.” [B. Runnegar to RMH, 4 March 2005]

p. 67 Biosignatures and Abiosignatures: This section is adapted from Hazen et al. (2002).

p. 70 biomolecular fragment: See the Web site www.biocyc.org for a database that illustrates many of the hundreds of common small molecules found in cells.

p. 72 microbial corrosion: Steele et al. (1994).

p. 72 Steelie’s assignment: Steele et al. (2000a, 2000b).

p. 73 the term “astrobiology”: Dick and Strick (2004, p. 205).

p. 73 Enspel, Germany: Toporski et al. (2002).

p. 75 MASSE: For information on the project development visit http://astrobiology.ciw.edu/main.php. The group proposes to look for morphological as well as chemical evidence (Cady et al. 2003). For an overview of Andrew Steele’s life-detection experiments, see Whitfield (2004). The difficulties of detecting life remotely on Mars are underscored by the ambiguous results of the Viking mission in the 1970s (Levin and Straat 1976, 1981).

INTERLUDE—GOD IN THE GAPS

p. 77 Darwinists rarely mention the whale: This quote comes from Alan Haywood’s (1985) Creation and Evolution. These sentiments are ech-

oed in Duane T. Gish’s (1985) Evolution: The Challenge of the Fossil Record, in which he says: “There are simply no transitional forms in the fossil record between marine mammals and their supposed land mammal ancestors…. It is quite entertaining, starting with cows, pigs, or buffaloes, to attempt to visualize what the intermediates may have looked like. Starting with a cow, one could even imagine one line of descent which prematurely became extinct, due to what might be called an “udder failure” (pp. 78-79).

p. 78 35-million-year-old Basilosaurus: Gingerich et al. (1990).

p. 78 Rodhocetus: Gingerich et al. (1994).

p. 78 Ambulocetus: Thewissen et al. (1994).

p. 78 new proto-whale species: Thewissen et al. (2001). See also the companion commentary by Muizon (2001).

p. 80 Michael Behe and William Dembski: Behe (1996) and Dembski (1999, 2004). For opposing views see, for example, Pennock (2002) and Forrest and Gross (2004).

p. 80 deeper problem: K. R. Miller (1999) presents a compelling case against the idea of “God in the gaps.”

6

STANLEY MILLER’S SPARK OF GENIUS

p. 83 “The idea that …”: S. L. Miller (1953, p. 528). Günter Wächtershäuser writes: “Oparin, in fact, never suggested such an atmosphere, as can be verified by reading his books of 1924 and 1938” [Günter Wächtershäuser to RMH, 24 June 2004]

p. 83 spontaneous generation: The complex story of spontaneous generation, a theory that persisted throughout the nineteenth century, is described by Farley (1977), Fry (2000), and Strick (2000).

p. 83 seventeenth-century invention: The invention of the microscope was to biology what the invention of the telescope was to astronomy. Discoveries of microorganisms, the cell, and even smaller internal cellular structures transformed biology. See Ford (1985).

p. 84 Lazzaro Spallanzani: See, for example, Dolman (1975) for a biographical account and bibliographic citations.

p. 84 Englishman John Needham: Westbrook (1974) provides a biographical sketch and bibliographic sources.

p. 84 Louis Pasteur: Pasteur’s motivation for these experiments in spontaneous generation is explored in Geison (1974), who also provides extensive bibliographic citations.

p. 85 In 1871, Charles Darwin: The letter is item 7471 in the Darwin online database: http://darwin.lib.cam.ac.uk. For a discussion of Darwin’s views, see Fry (2000, pp. 54-57).

p. 85 life requires liquid water: See, however, the intriguing speculations of Steven Benner of the University of Florida (Benner 2002), who warns against “Earth-o-centrism.” Perhaps, he notes, some other medium, such as liquid ammonia, might foster an alternative biochemistry on other worlds. Exploring this idea further, The Royal Society of London held a conference on “The Molecular Basis of Life: Is Life Possible Without Water?” December 3–4, 2003 (Ball 2004).

p. 86 Alexander Oparin: Oparin’s 1924 work first appeared in English in 1938 (Oparin 1924, 1938), but it was not widely available to English-speaking audiences until Bernal (1967), which included a translation. According to Günter Wächtershäuser, the rarely cited book Mechanische-Physiologische Theorie der Abstammungslehre by Swiss botanist Carl Wilhelm von Nägeli (1884) includes a prescient description of “the origin of life in a broth of emerging, growing and evolving protein particles.” [Günter Wächtershäuser to RMH, 24 June 2004]

p. 86 “primordial soup”: This phrase follows J. B. S. Haldane’s (1929) description of the early ocean as achieving “the consistency of hot dilute soup” (p. 247).

p. 86 J. B. S. Haldane: Haldane’s choice of The Rationalist Annual, a periodical largely devoted to the promotion of rationalism and secular education, may seem an odd one for a theoretical paper on origin-of-life chemistry. Cooke (2004) chronicles the colorful history of the Rationalist Press Association, including Haldane’s participation.

p. 87 chemist Harold Urey: Urey, a scientist of unusual breadth, won the 1934 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his discovery of deuterium, the heavy isotope of hydrogen and the essential component of “heavy water.” He was also an authority on Earth’s primitive atmosphere (Urey 1951, 1952), which led to his speculations about the prebiotic formation of organic compounds.

p. 87 Jeffrey Bada: Wills and Bada (2000).

p. 87 Scientists revere simple: Miller’s original article (S. L. Miller 1953) contains a rather sketchy outline of the experiment. Additional details are provided by S. L. Miller (1955) and Wills and Bada (2000).

p. 90 mid-February: Wills and Bada (2000, p. 47) quote Stanley Miller’s recollection of a mid-December 1953 submission. However, records in the Harold Clayton Urey papers (Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives) include a manuscript receipt from Science dated February 16, 1953. [Antonio Lazcano to RMH, 30 August 2004; Jeffrey Bada to RMH, 1 September 2004]

p. 90 Miller’s first publication: S. L. Miller (1953). The New York Times article, “Life and a glass Earth,” appeared on May 17, 1953, page E10.

p. 90 The Miller–Urey experiment: Historical perspectives are provided by Wills and Bada (2000) and Bada and Lazcano (2003).

While Miller has received widespread acclaim for his experiment, some scientists and historians are less convinced of the originality of the Miller–Urey research. Similar experiments were conducted decades earlier by the German chemist Walter Löb (1906, 1914), who employed similar apparatus and also succeeded in synthesizing the amino acid glycine (see Mojzsis et al. 1998). Löb’s research, however, was not designed to probe the chemistry of life’s origins, nor was it meant to mimic prebiotic environments.

p. 90 Independent confirmation: Miller’s experiments were repeated first by Hough and Rogers (1956) and Abelson (1956).

p. 90 Walter Löb: Löb (1906, 1914). Gustaf Arrhenius decries the lack of credit given to Löb. He states that the reverence accorded to the Chicago work is “an American myth originally based on cultural and linguistic ignorance, later on unwillingness to acknowledge the original work.” [Gustaf Arrhenius to RMH, 26 December 2004] In addition, Löb died at a relatively early age and was thus unable to promote his findings.

p. 91 John Oró: Oró (1960, 1961a). Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute chemist James Ferris and co-workers elaborated on the role of HCN in prebiotic chemistry (Ferris et al. 1978).

p. 91 Other chemists: See Shapiro (1988) for a measured assessment of efforts to synthesize ribose by plausible prebiotic pathways.

p. 92 Orgel and co-workers: Sanchez et al. (1966). It is important to note that global dilution need not imply local dilution. Regarding this point, Louis Allamandola writes: “This is where I think an exogenic ice/ice residue has a great intrinsic advantage over endogenous processes, even given the total amounts are small with respect to a planetary reservoir. These ices and residues are not dilute.” [Louis Allamandola to RMH, 6 July 2004]

p. 92 the longest experiments: The use of freezing to synthesize HCN polymers is related in Wills and Bada (2000, pp. 51-52).

p. 92 by the 1960s: The composition of the Archean Earth’s atmosphere is a matter of significant debate. Few scientists today accept Miller’s model atmosphere of methane, ammonia, and hydrogen. The majority view is that carbon dioxide and nitrogen were the dominant constituents of a relative unreactive atmosphere (H. D. Holland 1984; Walker 1986; Kasting 1990, 1993, 1994, 2001). Hiroshi Ohmoto of Pennsylvania State University, by contrast, has long argued that the early atmosphere featured significant oxygen content (Ohmoto et al. 1993, Ohmoto 1997). Tian et al. (2005) proposed an alternative hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

Nevertheless, it is likely that local pockets of reducing gases may have promoted organic synthesis. [Jack Szostak to RMH, 21 August 2004] Bada (2004) writes, “Even though reducing conditions may not have existed on a global scale, localized high concentrations of reduced gases may have existed around volcanic eruptions…. The localized release of reduced gases by

volcanic eruptions on the early Earth would likely have been immediately exposed to intense lightning” (p. 6).

p. 93 Miller and his supporters continue to counter: There is a kind of logic to the argument that the early atmosphere must have been reducing because the resulting synthesis mimics biochemistry. Orgel (1998a, p. 491) states, “It is hard to believe that the ease with which sugars, amino acids, purines and pyrimidines are formed under reducing-atmosphere conditions is either a coincidence or a false clue planted by a malicious creator.”

p. 93 “If God did not …”: as quoted in Wills and Bada (2000, p. 41).

p. 93 extremely dilute solution: The improbability of biochemical reactions arising from the dilute primordial soup has emerged as the central objection to the Miller hypothesis in the theories of Günter Wächtershäuser. In a dilute solution with hundreds or thousands of different solutes, the chance that a desired chemical reaction will occur between any two molecules is small. He states, “As far as I’m concerned, the soup theory is more of a myth than a theory, because it doesn’t explain anything.” (Hagmann 2002, p. 2007). For a more comprehensive critique, see Wächtershäuser (1994).

p. 93 another nagging problem: Stanley Miller himself often acknowledges this difficulty. In a 1992 Discover article, he said, “The first step, making the monomers, that’s easy. We understand it pretty well. But then you have to make the first self-replicating polymers…. Nobody knows how it’s done.” (Radetsky 1992, p. 78). Miller repeated this refrain in a 1998 Discover article: “It’s a problem. How do you make polymers? That’s not so easy.” (Radetsky 1998, p. 36).

7

HEAVEN OR HELL?

p. 95 “It is we …”: Gold (1999, p. v).

p. 96 Metabolism: For a useful overview of the surprising diversity of microbial metabolism, see Nealson (1997a).

p. 96 Our view of life: For a description of this research, see Radetsky (1992).

p. 97 On this particular dive: In 1979, scientists discovered that some of these vents spew out lots of dissolved minerals that precipitate in a thick black cloud as ocean and vent waters mix—a so-called “black smoker.”

p. 97 “Could the hydrothermal vents …”: Jack Corliss as quoted in Radetsky (1992, p. 76).

p. 97 others close to the story: [John Baross to RMH, 24 June 1998 and 10 March 2004; Sarah Hoffman to RMH, 23 July 2004] Jack Corliss did not respond to requests for information. Hoffman provided a 28-page docu-

ment with a detailed history of the development of the hydrothermal-origins hypothesis and its subsequent presentation at lectures and in print.

p. 98 “ideal reactors …”: Corliss et al. (1981, p. 62).

p. 98 much too hot: Several papers from the Miller group focus on the supposed instability of amino acids under hydrothermal conditions, including S. L. Miller and Bada (1988), Bada et al. (1995), and Bada and Lazcano (2002). Other authors attempted to counter these arguments (Holm 1992).

p. 98 “… a real loser”: Stanley Miller as quoted in Radetsky (1992, p. 82).

p. 99 Eventually the Corliss: The Corliss et al. (1981) paper appeared in a supplementary section of papers presented at a symposium on the “Geology of the Oceans,” which was part of the 26th International Geological Congress in Paris. A later paper was authored by Baross and Hoffman (1985).

p. 99 John Baross remains active: Much of John Baross’s recent work focuses on barophilic (pressure-loving) and thermophilic (heat-loving) microbes. See, for example, Baross and Deming (1995).

p. 99 Sarah Hoffman’s graduate: Corliss’s abandonment of origins research was underscored when he delivered a lecture on his origin hypothesis, “Emergence of Living Systems in Archean Sea Floor Hot Springs,” at the Geophysical Laboratory on January 8, 2001. The lecture offered no new insights beyond his work of the 1980s; indeed, he often interjected that “this is a 1986 lecture.” He seemed to forget many of the details of his model—temperatures, depths, organic chemistry—and his answers to several questions were vague and uninformative.

p. 100 Everywhere they looked: Dozens of recent books and articles document microbes in extreme environments (Madigan and Marrs 1997, Wharton 2002), including Antarctic ice (Price 2000, Thomas and Dieckmann 2002), boiling hot springs (Stetter et al. 1990, Hoffman 2001), acidic pools and streams (Zettler et al. 2002), deep-ocean hydrothermal zones (Pedersen 1993), and crustal rocks (Krumholz et al. 1997, Chapelle et al. 2002).

Concurrent with discoveries of abundant deep microbes were the findings of molecular biologist Carl Woese (Woese and Fox 1977; Woese 1978, 1987). Woese applied the techniques of molecular phylogeny to construct a tree of life (see Chapter 10). He discovered that the traditional divisions of life into five kingdoms was incorrect and that the most primitive living cells (i.e., microbes deeply rooted in the evolutionary tree of life) are extremophiles that live in hydrothermal conditions (Pace 1997). This result suggested to some researchers that the first life-forms might have been similar extremophiles. Such a conclusion is not certain, however, because life might have arisen in a cooler surface environment and subsequently radi-

ated into extreme environments. A large impact might then have killed off all surface organisms, leaving extremophiles as our last common ancestors.

p. 100 Savannah River: Frederickson and Onstott (1996) provide a popular account of this research.

p. 100 loaded with microbes: The Savannah River samples from a depth of 400 meters support from 100 to 10 million microbes per gram of rock. By comparison, a typical gram of topsoil might hold a billion microbes per gram.

p. 101 Subsequent drilling studies: Parkes et al. (1993), Stevens and McKinley (1995), Krumholz et al. (1997), Pedersen et al. (1997), Chapelle et al. (2002), and D’Hondt et al. (2002, 2004).

p. 101 Tullis Onstott: Frederickson et al. (1997), Colwell et al. (1997), Tseng and Onstott (1998) and Onstott et al. (1998). For popular accounts of this research, see Frederickson and Onstott (1996), Monastersky (1997), and Kerr (2002b).

p. 101 “It was ‘Don’t …’ ”: Schultz (1999, p. 1).

p. 102 Thomas Gold: Bondi (2004).

p. 103 In 1977: Gold (1977). The first peer-reviewed publication of these ideas appeared two years later (Gold 1979). See also Gold and Soter (1980).

p. 104 Siljan Ring: Gold (1999, pp. 105-123).

p. 104 Seven years: The controversy was summarized for Science by reporter Richard Kerr (1990). Additional points of view are provided by Donofrio (2003) and by reviewers of Gold’s book (Brown 1999, Margulis 1999, Parkes 1999, Von Damm 1999). Brown’s review in American Scientist, “Upwelling of Hot Gas,” is particularly contemptuous. Few authors seem to have considered the possibility of a middle ground. Might hydrocarbons arise from both surface life and from deep sources? After all, there’s a lot of carbon, and hydrocarbons happen.

p. 104 “the deep hot biosphere”: Gold (1992, 1997, 1999).

p. 104 invited Gold: The seminar, entitled “The Deep Hot Biosphere,” took place on April 28, 1998.

p. 105 Tommy Gold helped: Gold died on June 22, 2004, two weeks after suffering a massive heart attack. On June 7, 2004, he had sent me a preliminary review of the first half of this book. “The only comment I want to make before I have read it all very carefully is that you refer too often to the ocean vents,” he wrote. He argued that many other deep environments also contribute organic molecules and might have been more conducive to the origin of life. “But more about all this when I have read with some care what you sent me.” Sadly, that addendum never came. [Thomas Gold to RMH, 7 June 2004]

p. 105 Heaven Versus Hell: A version of this text appeared in Hazen (1998).

p. 106 ancient Mars or Venus: Speculations on the habitability of various bodies in the solar system include Reynolds et al. (1983), Sagan et al. (1992), Thompson and Sagan (1992), and Boston et al. (1992).

8

UNDER PRESSURE

p. 107 “Where is this …”: Wächtershäuser (1988a, p. 480).

p. 108 Geophysical Laboratory: High-pressure research at the Geophysical Laboratory is described in Hazen (1993) and Yoder (2004). For a general history of the Carnegie Institution, see Trefil and Hazen (2002).

p. 108 well funded by NASA: NASA’s Astrobiology Institute (NAI) was founded in 1998 with the Carnegie Institution as one of 11 charter research teams. Additional groups were added in 2001 and 2003. For more information, see the NAI Web site: http://nai.arc.nasa.gov.

p. 108 Our first experiments: Cody et al. (2000).

p. 108 In a later set of experiments: Brandes et al. (1998).

p. 108 Carrying on with this line: Brandes et al. (2000).

p. 109 “This proposal is based …”: S. L. Miller and Bada (1988, p. 609).

p. 109 “a real loser”: Stanley Miller as quoted in Radetsky (1992, p. 82).

p. 110 again and again: These quotes appear in Wills and Bada (2000, pp. 98 and 101). “Ventists,” annoyed at this condescending label, have been known to refer to Bada and colleagues as “Millerites”—or, after a couple of beers, “Miller lites.” In fact, the name “ventists” was coined by RPI chemist James Ferris, who also dubbed Miller and his followers “arcists” (as quoted in Simoneit 1995, p. 133).

p. 111 roles as varied: The possible roles of minerals in life’s origin are reviewed by Hazen (2001).

p. 111 “Before enzymes …”: Wächtershäuser’s ideas initially appeared in four papers (Wächtershäuser 1988a, 1988b, 1990a, 1990b). The central tenets were summarized in “Pyrite formation, the first energy source for life: A hypothesis” (Wächtershäuser 1988b), which emphasizes the role that Popperian philosophy played in the theoretical effort. That paper was submitted to Systematic Applied Microbiology in March of 1988 and published later that year. A more elaborate presentation, “Before enzymes and templates: Theory of surface metabolism” (Wächtershäuser 1988a) soon followed in Microbiology Review. The paper that first brought his ideas to the

attention of a wide audience appeared two years later in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Wächtershäuser 1990a). Articles submitted to the Proceedings are often communicated by an Academy member; Wächtershäuser’s paper, “Evolution of the first metabolic cycles,” was sponsored by Karl Popper himself. The full-blown theory is articulated in the massive “Groundworks for an evolutionary biochemistry: The iron–sulfur world” (Wächtershäuser 1992). Several subsequent papers clarify and elaborate on the model and respond to a growing barrage of comment and criticism (Wächtershäuser 1993, 1994, 1997).

p. 111 Karl Popper: Popper’s key ideas are summarized in three of his books, The Logic of Scientific Discovery (Popper 1959), Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (Popper 1963), and Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach (Popper 1972). Wächtershäuser’s presentation of his own hypothesis in terms of “Theory Darwinism” (essentially, competition among rival hypotheses and survival of the fittest) is most clearly presented in Wächtershäuser (1988a).

p. 111 “During breakfast …”: As quoted in Nicholas Wade, “Gunter Wachtershauser: Amateur Shakes up on Recipe for Life” (New York Times, April 22, 1997).

p. 112 patched together a theory: A number of widely cited origin-of-life hypotheses, including those based on a primordial soup, can be criticized for their poor predictive ability.

p. 113 “You don’t mind …”: Günter Wächtershäuser as quoted in Radetsky (1998, p. 36). Experiments designed to test aspects of Wächtershäuser’s theory include Blöchl et al. (1992), Keller et al. (1994), Huber and Wächtershäuser (1997, 1998), and Huber et al. (2003).

p. 113 “It takes maybe two weeks”: Günter Wächtershäuser in response to Robert Hazen at his Geophysical Laboratory seminar, March 23, 1998. Other estimates vary widely. De Duve (1995b, p. 428) suggests, “millennia or centuries, perhaps even less.” See also Lazcano and Miller (1994) and Fry (2000, pp. 125-126).

p. 113 “not a new idea”: Bada and Lazcano (2002, p. 1983). The paper they refer to, “A note on the origin of life” (Ycas 1955), introduces the idea of an autocatalytic cycle of metabolites as the first living system. Dick and Strick (2004, p. 64) agree that “Ycas had pioneered the ‘metabolism first’ idea.” However, Noam Lahav notes that Alexander’s (1948) discussion of autocatalysis predates that of Ycas. [Noam Lahav to RMH, 27 August 2004]

p. 114 January 1998: “We have not met, but your work of the past decade on the role of sulfides in organic synthesis and the origin of life is having a profound effect on our current research,” I wrote. “We would be delighted if you could schedule a trip to the States, for which we would pay expenses.” [RMH to Günter Wächtershäuser, 14 January 1998]

p. 114 Wächtershäuser delivered his lecture: The Geophysical Laboratory seminar, “Chemoautotrophic Origin of Life in an Iron–Nickel–Sulfur World,” took place on March 23, 1998.

p. 114 “We would like to explore …”: [RMH to Günter Wächtershäuser, 8 April 1998]

p. 115 I was left: That memorable meeting was the last contact any of us had with Günter Wächtershäuser until Harold Morowitz received a stern letter on Wächtershäuser & Hartz legal stationary dated October 11, 2000. Copies of the letter were also sent to the bosses of everyone involved, including Bruce Alberts, president of the National Academy of Sciences; Maxine Singer, president of the Carnegie Institution; and Alan Merten, president of George Mason University. Harold Morowitz, with three coauthors (including George Cody), had recently published a short article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on life’s most primitive metabolic cycle. Morowitz et al. (2000) proposed that molecules used in the so-called “reductive citric acid cycle” (what I refer to in the text as the “reverse citric acid cycle”) are highly selected, with a long list of distinctive features. Such selectivity, Harold concluded, suggests that life’s earliest metabolism is deterministic and likely to be the same on any planet or moon where life emerges. Wächtershäuser denounced the article as improperly claiming credit for ideas that were originally his, and he demanded an immediate retraction. Harold ignored the veiled threat of legal action, but we were saddened that a brilliant man with such creativity and vision could so remove himself from the cooperative spirit of scientific research.

p. 115 His first paper: Brandes et al. (1998).

p. 115 He followed up: Brandes et al. (2000).

p. 115 In spite of these successes: Bada et al. (1995). The hydrothermal stability of amino acids is also discussed by Shock (1990b), Hennet et al. (1992), and W. L. Marshall (1994).

p. 116 a few centuries: Wolfenden and Snider (2001).

p. 116 preserve proteins: Recent studies on the essential bone protein osteocalcin underscores the ability of minerals to stabilize organic molecules. Hoang et al. (2003) document the complex structure of osteocalcin and illustrate how it binds strongly to hydroxyapatite, the principal mineral constituent of bone. This binding not only provides strength and flexibility to bone but also protects osteocalcin from the rapid decay experienced by most other proteins. Christine Nielsen-Marsh and co-workers at the University of Newcastle (Nielsen-Marsh et al. 2002) exploit this feature to extract and sequence osteocalcin from fossil bison bones more than 50,000 years old. Over time, osteocalcin undergoes slight mutations in its amino acid sequence. Comparison of small differences in this sequence among fossils of various species and ages thus reveals patterns of mammalian evolution.

Bruce Runnegar writes, “I’m skeptical of the report of collagen in dinosaur bone. Osteocalcin maybe, but I wait to be convinced about collagen.” [B. Runnegar to RMH, 4 March 2005]

p. 116 Additional evidence: Lemke et al. (2002) and Ross et al. (2002a, 2002b).

p. 117 molecules might separate out: The idea of the separation from water of an amino-acid-rich phase first appeared in von Nägeli (1884). This idea was also a central feature of Oparin’s original hypothesis (Oparin 1924, 1938), as well as several subsequent proposals. See, for example, Fox and Harada (1958) and Fox (1965, 1988).

p. 117 more work to be done: In spite of these results, David Ross emphasizes that amino acids cannot survive long enough in a hydrothermal environment to start life. “The utility of hydrothermal work is that it allows us to accelerate reactions to convenient times so that we can study them. No more than that…. The key reactions leading to life involved very, very slow reactions. Half-lives of a million years or more would be the order of the day, and it would take a graduate student of unusual longevity, durability, and endurance to get any data on such reactions.” [David Ross to RMH, 14 July 2004]

p. 118 Such reactions occur rapidly: These experiments are detailed in Cody et al. (2004).

p. 118 Fischer–Tropsch (F–T) synthesis: A number of researchers have studied F–T synthesis under hydrothermal conditions (McCollom and Simoneit 1999, McCollom and Seewald 2001, Foustoukos and Seyfried 2004).

p. 118 Recent intriguing analyses: Sherwood-Lollar et al. (1993, 2002).

p. 119 thiols and thioesters: The possible role of these sulfur-containing compounds in life’s origins has been detailed by de Duve (1995a, 1995b).

9

PRODUCTIVE ENVIRONMENTS

p. 121 “The limits of life …”: Nealson (1997b, p. 23677). Nealson notes that the quote appeared “again in slightly different form in 1998 in a Caltech lecture, and in the final form in Nealson and Conrad (1999).”

p. 121 immense tenuous clouds: Ehrenfreund and Charnley (2000) enumerate several types of interstellar structures where organic synthesis occurs. The density of these structures ranges from about one atom per cubic centimeter in “interstellar clouds” to a million atoms per cubic centime-

ter in “dense molecular clouds.” Louis Allamandola writes: “A volume roughly the size of a large auditorium is home to only one tenth-micronsized dust grain. It is the dust which absorbs background starlight, making dark interstellar molecular clouds dark. Thus their sizes are enormous, often measured in thousands of light-years.” He notes that in these clouds, PAHs, which are produced primarily during earlier star-formation processes, are more abundant than all other interstellar molecules combined. [Louis Allamandola to RMH, 16 July 2004]

p. 122 more than 140 different compounds: Infrared spectroscopy of molecular clouds is reviewed by Pendleton and Chiar (1997) and Rawls (2002). An up-to-date list of all identified interstellar molecular species is available at: http://www-691.gsfc.nasa.gov/cosmic.ice.lab/interstellar.htm.

p. 122 Allamandola and co-workers’ experiments: See, for example, Bernstein et al. (2002). A lively, accessible, and richly illustrated account of this research appears in Scientific American (Bernstein et al. 1999a). Similar experiments have been performed by a research team based at the Leiden Observatory in The Netherlands (Muñoz Caro et al. 2002).

James Ferris writes: “[Allamandola] spent a good part of his career working in Mayo Greenberg’s lab in Leiden before going to Ames. Greenberg developed this apparatus and approach and Allamandola adopted the design after going to Ames.” [James Ferris to RMH, 22 August 2004]

p. 123 Evidence from space: Reviews of the rich variety of organic molecules recovered from meteorites include Cronin and Chang (1993), Glavin et al. (1999), Becker et al. (1999), Ehrenfreund and Charnley (2000), and Cody et al. (2001a). Cometary organic molecules, though less well documented, are described by Chyba et al. (1990) and Ehrenfreund and Charnley (2000). Kwok (2004) also emphasizes the important role of “proto-planetary nebulae”—the envelopes of gas and dust around newly forming stars—in the production of organic molecules. See also Oró (1961b), Urey (1966), Kvenvolden et al. (1970), Cronin and Pizzarello (1983), Anders (1989), Cronin (1989), Delsemme (1991), Engel and Macko (1997), Irvine (1998), and Pizzarello and Cronin (2000).

p. 123 seeded abundantly: Allamandola argues that interstellar ice particles could have provided much more than simple organic building blocks. “These could well have been a source of prebiotic/biogenic molecules which played a specific role in the origin of life. Going even further, I am beginning to think we should also consider the possibility that the chemistry in these ices might be even more advanced, perhaps being a fountainhead of life” [Louis Allamandola to RMH, 16 July 2004]

p. 123 “that’s garbage …”: Stanley Miller as quoted by Radetsky (1992, p. 80).

p. 123 “Even if cosmic debris …”: Jeffrey Bada as quoted by Radetsky (1998, p. 37). More recently Bada (2004, p. 7) has softened his objections and points to a combination of sources: “It is now generally assumed that the inventory of organic compounds on the early Earth would have been derived from a combination of both direct Earth-based syntheses and inputs from space.”

p. 123 It’s hard to imagine: In the mid-1990s, when NASA scientists subjected carbon-rich meteorite fragments to realistic impact velocities of 3 miles per second, about 99.9 percent of the amino acids were obliterated (Peterson et al. 1997). They concluded that impact velocities of the Murchison and other amino-acid-bearing meteorites must have been significantly less, perhaps owing to aerobraking, thus preserving more of the delicate organic molecules.

p. 123 impacts don’t destroy all: Other shock experiments to induce organic synthesis have been reported by C. P. McKay and Borucki (1997), who used a high-energy infrared YAG laser to shock-heat a gaseous sample to temperatures greater than 10,000°C. These experiments simulate the effects of an impact on the atmosphere.

p. 123 giant experimental gas gun: See Blank et al. (2001).

p. 124 idea of Friedemann Freund: Freund et al. (1980, 1999, 2001).

p. 124 “Maybe,” he remarked: Friedemann Freund to Wesley Huntress, undated note ca. 2000 attached to a copy of Freund et al. (1999).

p. 125 “I am a hundred percent sure …”: [Anne M. Hofmeister to RMH, 21 November 2002]

p. 125 synthetic magnesium oxide: Crystal growth of MgO is described by Freund et al. (1999), who also document the identity of extracted carboxylic acids. Freund’s studies on MgO properties include Kathrein and Freund (1983), Kötz et al. (1983), and Freund et al. (1983).

p. 126 gem-quality olivine: Freund’s olivine samples come from the classic San Carlos, New Mexico, locality, which is an active gem-producing area. The gemmy green olivine crystals (also known as peridot), as much as an inch across, comprise up to 50 percent of the basaltic rock, which was formed deep in the crust. Samples are widely available commercially, but the outcrops occur on the San Carlos Indian reservation, so access and collecting is restricted.

p. 126 100 parts per million carbon: Keppler et al. (2003) disagree with this claim for San Carlos olivine. Their experiments on olivine growth under carbon-saturated conditions produced crystals with no more than 0.5 part per million carbon.

p. 126 “I ran a sample …”: [George R. Rossman to Anne M. Hofmeister, 20 December 2002] Many mineralogists and solid-state chem-

ists discount Freund’s findings as experimental artifacts resulting from surface contamination. See, for example, Keppler et al. (2003) and M. Wilson (2003).

p. 127 no single dominant source: A few authors imply that it remains a mystery which of several sources of organic molecules—Miller-type surface synthesis, hydrothermal processes, impacts, or deep-space synthesis—was dominant. Orgel (1998a, p. 491), for example, states: “Three popular hypotheses attempt to explain the origin of prebiotic molecules: synthesis in a reducing atmosphere, input in meteorites and synthesis on metal sulfides in deep-sea vents. It is not possible to decide which is correct.” Similarly, Miller and his colleagues have at times discounted both hydrothermal zones and extraterrestrial sources as trivial (S. L. Miller and Bada 1988; Stanley Miller and Jeffrey Bada as quoted in Radetsky 1992, 1998). Other more ecumenical estimations of multiple organic sources include Chyba and Sagan (1992) and Lahav (1999).

INTERLUDE—MYTHOS VERSUS LOGOS

p. 129 “People of the past …”: Armstrong (2000, p. xiii). She continues, “Myth looked back to the origins of life, to the foundations of culture, and to the deepest levels of the human mind. Myth was not concerned with practical matters, but with meaning.” By contrast, “Logos was the rational, pragmatic, and scientific thought.” Armstrong argues, “People of Europe and America [have] achieved such astonishing success in science and technology that they began to think that logos was the only means to truth and began to discount mythos as false and superstitious.”

p. 129 “Whoa, …”: [Margaret H. Hazen to RMH, 30 May 2004]

10

THE MACROMOLECULES OF LIFE

p. 133 “To purify …”: Lehninger et al. (1993, p. 5).

p. 133 One of the transforming discoveries: Lehninger et al. (1993). The extraordinary Web site http://biocyc.org/ECOO157/new-image?object=Compounds tabulates all known small organic molecules from the microbe Escherichia coli.

p. 134 “I can no longer …”: Friedrich Wöhler to his teacher Jacob Berzelius, February 28, 1828. This discovery (Wöhler 1828) was made in the same year that Wöhler isolated and named the element beryllium.

p. 134 Four key types of molecules: For an overview of the character-

istics of sugars, amino acids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids, see Lehninger et al. (1993).

p. 135 Sugars are the basic building blocks: Estimates of Earth’s total biomass place cellulose, the abundant glucose polymer that forms leaves, stems, trunks, and other plant support structures, at the top of the list (Lehninger et al. 1993, pp. 298 et seq).

p. 135 For every useful molecule: Of the several proposed prebiotic mechanisms for biomolecular synthesis, Miller’s original spark experiments produce perhaps the highest percentage of useful molecules. Fully 6 percent of the carbon atoms introduced as CH4 in some of his experiments were incorporated into amino acids, for example (S. L. Miller and Urey 1959a). For this reason alone, Miller and his supporters often argue that electric discharge in a reducing atmosphere is the most likely origin scenario.

p. 136 life is even choosier: See, for example, Bonner (1995). The problem of chiral selection is discussed in more detail in Chapter 13.

p. 136 molecular phylogeny: See, for example, Pace (1997), Pennisi (1998), and Sogin et al. (1999).

p. 137 The Canterbury Tales: Barbrook et al. (1998). Similar techniques of textual comparison have long been employed for shorter manuscripts, but this study used the same computer algorithms as applied to genomic data.

p. 138 Carl Woese: The original proposal for three domains of life, including the Archaea, appears in Woese and Fox (1977). See also Woese (1978, 1987, 2000, 2002). A biographical sketch of Carl Woese, including an overview of his work, is provided by Morell (1997).

p. 139 thrive at elevated temperature: Perspectives on the proposition that the last common ancestor was an extremophile are provided, for example, by Gogarten-Boekels et al. (1995), Forterre (1996), and Reysenbach et al. (1999).

Bruce Runnegar writes, “There is a last common ancestor and it was a highly derived organism. It tells us very little about Earth’s earliest cells in the same way that living birds do not reveal the attributes of dinosaurs.” [B. Runnegar to RMH, 4 March 2005]

p. 141 swap sections of DNA: Gogarten et al. (1999), Doolittle (2000), and Woese (2002).

p. 141 “last common ancestor”: See, for example, Woese (1998) and Ellington (1999). An important conclusion of recent studies is that, because of gene transfer, there is no single last common cellular ancestor. Woese (1998, p. 6854) writes: “The universal ancestor is not a discrete entity. It is, rather, a diverse community of cells that survives as a biological unit. The universal ancestor has a physical history but not a genealogical one.”

p. 141 all cells employ RNA: Woese (2002).

p. 141 simple metabolic strategy: Woese (1998, p. 6855) states that the biochemical repertoire of the universal ancestor included “a complete tricarboxylic acid cycle, polysaccharide metabolism, both sulfur oxidation and reduction, and nitrogen fixation.” Pace (1997, p. 734) comments that “the earliest life was based on inorganic nutrition.”

p. 142 primordial “oil slick”: Lasaga et al. (1971). See also Morowitz (1992).

11

ISOLATION

p. 143 “The self-assembly process …”: Deamer (2003, p. 21).

p. 143 Lipid molecules: For an accessible overview of lipid molecules and their spontaneous organization into bilayers, see Tanford (1978) and Segré et al. (2001).

p. 144 Alec Bangham: See, for example, Bangham et al. (1965). Some researchers initially called these structures “banghasomes.” [Harold Morowitz to RMH, 10 August 2004]

p. 144 Luisi and co-workers: Luisi (1989, 2004), Luisi and Varela (1989), Luisi et al. (1994), Bachmann et al. (1992), and Szostak et al. (2001). See also Segré et al. (2001).

p. 145 counted as classics: Pasteur (1848), Miller (1953), and Bernstein et al. (1999b).

p. 146 Deamer returned: Deamer and Pashley (1989). For additional information, see Zimmer (1993) and Deamer and Fleischaker (1994).

p. 146 Murchison meteorite: For a description of the Murchison meteorite and related research, see Grady (2000, pp. 350-352).

p. 147 Their straightforward procedure: The eclectic mix of organic molecules in Murchison included some species, like amino acids, that were soluble in water; some, like lipids, that were soluble in chloroform or other organic solvents; and a complex tarry residue, called by the generic name “kerogen,” which is difficult to analyze. Recent studies by Cody et al. (2001a) suggest that this residue consists of a complexly linked mass of rings, chains, and other smaller groups of atoms. It is not evident that such insoluble matter could have played much of a role in prebiotic chemistry.

p. 148 breakthrough moment: The discovery paper by Deamer and Pashley (1989) was entitled “Amphiphilic components of the Murchison carbonaceous chondrite: Surface properties and membrane formation.” In this article they state, “If amphiphilic substances derived from meteoric infall and chemical evolution were available on the prebiotic earth following condensation of oceans, it follows that surface films would have been present at air-water interfaces…. This material would thereby be concentrated for

self-assembly into boundary structures with barrier properties relevant to function as early membranes.”(p. 37) This paper was especially noteworthy because it followed by a year the publication of a theoretical paper by Morowitz et al. (1988) that proposed such an origin scenario.

p. 148 NASA Ames team: Dworkin et al. (2001).

p. 149 a colorful photograph: The Washington Post (Kathy Sawyer, “IN SPACE; CLUES TO THE SEEDS OF LIFE,” January 30, 2001, p. A1).

p. 149 astrobiology meetings: The First Astrobiology Science Conference was held April 3–5, 2000, at the NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. Deamer’s lecture was entitled “Self-assembled Vesicles of Monocarboxylic Acids and Alcohols: A Model Membrane System for Early Cellular Life” (Apel et al. 2000).

p. 151 we had made bilayer membranes: These results were reported at the 221st Annual Meeting of the American Chemical Society, held in San Diego, California, April 1-5, 2001.

p. 151 Recent work: Knauth (1998) provides estimates of higher salinity in the Archean ocean. Salt inhibition of amphiphile self-organization is reported in Monnard et al. (2002).

p. 152 atmospheric aerosols: Dobson et al. (2000). See also Ellison et al. (1999), Tuck (2002), and Donaldson et al. (2004). These studies, which present theoretical analyses of aerosol dynamics and atmospheric residence times, build on earlier speculative comments regarding the possible roles of aerosols by Woese (1978) and Lerman (1986, 1994a, 1994b, 1996). Regarding Lerman’s contributions, James Ferris writes: “Unfortunately a head injury in an automobile accident had a major effect on his life and he was unable to get a full paper written on this proposal. He discussed this proposal at meetings and it was well known in the origins of life community.” [James Ferris to RMH, 22 August 2004].

12

MINERALS TO THE RESCUE

p. 155 “But I happen to know …”: Updike (1986, pp. 328-329).

p. 155 The first living entity: Portions of this chapter were adapted from Hazen (2001).

p. 156 Mineralogist Joseph V. Smith: J. V. Smith (1998), Parsons et al. (1998), and J. V. Smith et al. (1999). Other authors, including Cairns-Smith et al. (1992), have also proposed that porous minerals might have provided a measure of protection for proto-life.

p. 157 a primitive slick: The oil-slick hypothesis was championed by Morowitz (1992) in his influential book The Beginnings of Cellular Life: Metabolism Recapitulates Biogenesis. See also Lasaga et al. (1971), who estimated

that a primordial oil slick on the Archean ocean could have achieved a thickness of 1 to 10 meters.

p. 157 British biophysicist John Desmond Bernal: Bernal (1949, 1951). The Swiss-born geochemist Victor Goldschmidt also suggested that minerals played a role in life’s origin, but his thoughts, presented as a lecture in 1945 and published posthumously (Goldschmidt 1952), had little impact on the origins community (Lahav 1999, p. 250).

p. 157 In a 1978 study: Lahav et al. (1978). See also Lahav and Chang (1976) and Lahav (1994).

p. 157 NASA-sponsored teams: Among the chemists who have studied roles of clays and other fine-grained minerals in prebiotic processes, two NASA Specialized Center of Research and Training (NSCORT) groups at Scripps Institution of Oceanography (La Jolla, California) and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (Troy, New York) have made notable contributions.

p. 157 James Ferris: Reports by Ferris and colleagues on mineral-induced polymerization of RNA, principally by the common clay montmorillonite and the phosphate hydroxyapatite, include Ferris (1993, 1999), Holm et al. (1993), Ferris and Ertem (1992, 1993), Ferris et al. (1996), and Ertem and Ferris (1996, 1997). Images of organic molecules on ideally smooth mineral surfaces have been published, for example, by Sowerby et al. (1996) and Uchihashi et al. (1999).

p. 157 “activated” RNA: Ferris writes: “My experiments work only if activated nucleotides are reacted. The thermodynamics is against self-condensation of nucleotides to form the phosphodiester bond in aqueous solution. That’s why nature uses ATP in place of AMP to form RNA. By the way, ATP and ADP do not work in the clay catalyzed reaction so we use the imidazole activating group that was introduced first by other workers and popularized by Lohrmann and Orgel.” [James Ferris to RMH, 22 August 2004]

p. 158 Leslie Orgel: Experiments on polypeptide formation are described in Ferris et al. (1996), Hill et al. (1998), and Liu and Orgel (1998).

p. 158 “polymerization on the rocks”: Orgel (1998b). See also Acevedo and Orgel (1986).

p. 158 One possible answer: Chen et al. (2004). Subsequent work by Szostak’s group reveals that a wide variety of powdered minerals promotes similar vesicle formation.

p. 159 Gustaf Arrhenius: Arrhenius and co-workers’ studies of double-layer hydroxides appear in Arrhenius et al. (1993), Gedulin and Arrhenius (1994), and Pitsch et al. (1995).

p. 160 Joseph Smith: Smith’s mineralogical proposal on “Biochemical evolution” appeared in J. V. Smith (1998), Parsons et al. (1998), and J. V. Smith et al. (1999).

p. 160 A. G. (Graham) Cairns-Smith: The clay-life hypothesis first

appeared in “The structure of the primitive gene and the prospect of generating life” (manuscript dated October 1964). The first publication was Cairns-Smith (1968); see also Cairns-Smith (1977). Important book-length elaborations include Genetic Takeover and the Mineral Origins of Life (Cairns-Smith 1982) and Clay Minerals and the Origin of Life (Cairns-Smith and Hartman 1986). Popular accounts of these ideas include Seven Clues to the Origin of Life (Cairns-Smith 1985a) and a Scientific American article, “Clays and the origin of life” (Cairns-Smith 1985b).

p. 160 “I believe …”: Cairns-Smith (1985b, p. 900).

p. 160 “Evolution did not …”: Cairns-Smith (1985a, p. 107).

p. 161 “The answer”: Cairns-Smith (1985b, pp. 91-92).

p. 161 “I’m an organic chemist …”: A. G. Cairns-Smith seminar, “Clay Minerals and the Origin of Life,” Carnegie Institution, June 16, 2003.

p. 162 clay minerals commonly display: Varieties of clay defects are illustrated in Cairns-Smith (1988, 2001).

p. 162 “In two-dimensional …”: Cairns-Smith (1985b, p. 96).

p. 163 particularly stable sequences: Cairns-Smith writes: “The word stable sounds like thermodynamically most stable whereas in fact any informational structure has to be at least a little bit unstable. Like any genetic information it would owe its prevalence to indirect effects that favour its own survival and/or propagation—e.g., suppose that a particular defect arrangement catalyses (a little bit) the production of di- or tri-carboxylic acids, which in turn assist clay synthesis by transporting aluminum.” [A. Graham Cairns-Smith to RMH, 31 August 2004]

p. 164 In 1988: Cairns-Smith (1988).

p. 164 “The first step …”: Cairns-Smith (1988, p. 244).

p. 164 “Can the material …”: [A. Graham Cairns-Smith to RMH, 18 December 2003]

13

LEFT AND RIGHT

p. 167 “Assemblage on corresponding …”: Goldschmidt (1952, p. 101).

p. 167 One of the stages: A vast literature addresses the origin of biological chirality. Comprehensive reviews have been presented by Bonner (1991, 1995).

p. 169 global excess: Meticulous analyses of amino acids in some meteorites have revealed a small but significant excess of L-amino acids (Cronin and Pizzarello 1983, Engel and Macko 1997, and Pizzarello and Cronin 2000).

p. 169 Louis Pasteur: Pasteur (1848).

p. 169 polarized light: Numerous recent articles explore this idea (S. Clark 1999, Podlech 1999, and Bailey et al. 1998).

p. 169 parity violations: See, for example, Salam (1991).

pp. 169-170 local, as opposed to global: Some authors claim that an important philosophical distinction exists between deterministic global models of life (i.e., that some intrinsic feature of the universe demands left-handed amino acids) versus a chance local selection of left or right (i.e., life might have formed either way through stochastic processes). Note, however, that of the many symmetry-breaking models proposed, parity violations in beta decay provide the only truly universal chiral influence. Most authors conclude that this effect is so small as to be negligible in any realistic calculations of chiral selection (Bonner 1991, 1995). All other proposed symmetry-breaking mechanisms are local, though at vastly different scales (i.e., Popa 1997). Circularly polarized light from rapidly rotating neutron stars, for example, may selectively break down right-handed amino acids in one substantial volume of galactic space but will have the opposite effect in other volumes. Even if such a scenario led to a preponderance of left-handed amino acids in our region of the galaxy, an equal volume of space would have featured an excess of right-handed molecules.

p. 170 local environments abounded: Goldschmidt (1952), Lahav (1999), and Hazen (2004).

p. 171 Albert Eschenmoser: Eschenmoser (1994, 2004) and Bolli et al. (1997).

p. 173 For most of the twentieth century: For example, Ferris and Ertem (1992, 1993), Arrhenius et al. (1993), Gedulin and Arrhenius (1994), Pitsch et al. (1995), Ferris et al. (1996), Ertem and Ferris (1996, 1997), Hill et al. (1998), Liu and Orgel (1998), J. V. Smith (1998), Parsons et al. (1998), and J.V. Smith et al. (1999). See Chapter 12.

p. 173 three separate points: See, for example, Davankov (1997).

p. 173 By the 1930s: Tsuchida et al. (1935) and Karagounis and Coumonlos (1938). More recent work by Bonner et al. (1975) casts doubt on these accounts.