Genesis: The Scientific Quest for Life's Origin (2005)

Chapter: Part III The Emergence of Macromolecules -- 10 The Macromolecules of Life

Part III

The Emergence of Macromolecules

The beginning and end points of life’s emergence on Earth seem reasonably well established. At the beginning, more than 4 billion years ago, life’s simplest molecular building blocks—amino acids, sugars, hydrocarbons, and more—emerged inexorably through facile chemical reactions in numerous prebiotic environments, from deep space to the deep crust. A half-century of compelling synthesis research has amplified Stanley Miller’s breakthrough experiments. Potential biomolecules must have littered the ancient Earth.

The end point of life’s chemical origin was the emergence of the simple, encapsulated precursors to modern microbial life, with all of life’s essential traits: the ability to grow, to reproduce, and to evolve. Top-down studies of the fossil record hint that such cellular life was firmly established almost 4 billion years ago.

The great mystery of life’s origin lies in the huge gap between molecules and cells. Ancient Earth boasted oceans of promising biomolecules but, like a pile of bricks and lumber at a building supplier, more than a little assembly was required to achieve a useful structure. Life requires the organization of just the right combination of small molecules into much larger collections—macromolecules with specific functions. Making macromolecules from lots of little molecules may sound straightforward, but what most books don’t mention is that for every potentially useful small molecule in that prebiotic environment, there were dozens of other molecular species with no obvious role in modern biology. Life as we know it is incredibly picky about its building blocks; the vast majority of carbon-based molecules synthesized in prebiotic processes have no obvious biological use whatsoever. That’s why, in laboratories around the world, many origins researchers have shifted their focus to the emergent steps by which just the right molecules might have been selected, concentrated, and organized into the essential structures of life.

10

The Macromolecules of Life

To purify and characterize thoroughly all [biomolecules] would be an insuperable task were it not for the fact that each class of macromolecules … is composed of a small, common set of monomeric units.

Lehninger et al., Principles of Biochemistry, 1993

We are chemical beings. Every living organism, from the simplest microbes to multicellular fungi, plants, and animals, incorporates thousands of intricate molecular components. All of nature’s diverse life-forms grow, develop, reproduce, and respond to changes in their external environment—vital tasks that must be accomplished by exquisitely balanced cascades of chemical reactions.

The more biologists learn about life, even the most “primitive” single-celled organisms, the more amazingly complex life seems to be. Everywhere you look, living entities have found their niche, and they survive in wonderfully varied ways. Indeed, in a sense, chemical complexity seems synonymous with life. Yet emergent systems, however complex, are usually built from relatively simple parts, and life is no exception.

One of the transforming discoveries of biology is that all known life-forms rely on only a few basic types of chemical reactions, and these reactions produce a mere handful of molecular building blocks. Virtually all of life’s essential construction materials are carbon-based organic molecules that combine by the thousands to form layered enclosures or chainlike polymers. In every instance, just a few kinds of small molecules assemble into a great variety of larger structures.

In the early nineteenth century, conventional wisdom held that life’s chemical compounds formed by their own mysterious rules, perhaps governed by a “vital force.” Many scholars assumed that the na-

scent science of chemistry applied only to the inorganic world—the world of rocks, minerals, and metals. This perception changed in 1828, when the young German chemist, mineral collector, and gynecologist Friedrich Wöhler demonstrated that biological molecules are no different in principle from other chemicals. He combined the common laboratory reagent cyanic acid with ammonia and succeeded in producing urea, which is extracted in the kidneys and found in urine. Wöhler’s letter announcing his important discovery displayed a sense of whimsy not always associated with German academicians: “I can no longer, as it were, hold back my chemical urine: and I have to let out that I can make urea without needing a kidney, whether of man or dog.” By employing straightforward lab techniques to produce a chemical substance known only from life, Wöhler convinced his colleagues of the ordinariness of organic chemistry.

MODULAR LIVING

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of the molecules of living organisms is their modular design. This familiar strategy is similar to that of modern architects, who rely for the most part on standard building materials. They use mass-produced bricks, beams, windows, doors, stairs, lighting fixtures, and so on to assemble an almost infinite variety of commercial and private buildings.

You don’t have to build in that way. A multimillionaire acquaintance recently created the most extraordinary mansion, with every square foot of walls and floor, every light and bath fixture, every door and window custom-designed and hand-crafted. It’s an amazing house, with secret passages, unexpected nooks, and hidden closets, all lovingly constructed of the finest woods, stone, and other extravagant materials. Such personalized craftsmanship is wonderful to see, but inordinately expensive. Most of us choose a more economical path. By relying on a few standard construction modules, buildings are faster and cheaper to design and build. But modularity doesn’t imply uniformity. You can design a unique dwelling of almost any size or shape from simple components available through any hardware or building supply store.

The same modular principle holds for life’s carbon-based molecular building blocks. Four key types of molecules—sugars, amino acids, nucleic acids, and hydrocarbons—exemplify life’s chemical parsimony.

Sugars are the basic building blocks of carbohydrates, Earth’s most abundant biomolecules. Many common sugars in our diets, including the fructose of honey, the sucrose of cane sugar, and the glucose of fruits, are small molecules consisting of at most a few dozen atoms. These energy-rich molecules incorporate carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen typically in about a 1:1:2 ratio. But most of life’s sugar molecules are locked into macromolecules—countless individual sugar molecules linked together to form giant polymers, such as the fibrous cellulose of plant stems or the bulky starch of potatoes.

Amino acids are small molecules that link together to form proteins. Proteins serve as the chemical workhorses of life, with myriad vital functions: They form tissues and strengthen bone; they act as hormones to control glandular functions; they clot blood, digest food, and promote the thousands of chemical operations essential to life. All proteins form from long chains of hundreds to thousands of individual amino acid molecules, lined up like beads on a string. These chains fold into the most wonderful shapes, each protein folded in such a way as to accomplish a specific chemical task.

The vital genetic molecules DNA and RNA are also lengthy chainlike polymers, assembled from small molecules called nucleotides. Each nucleotide, in turn, is constructed from three small molecular parts: a 5-carbon sugar (ribose in RNA, its cousin deoxyribose in DNA); a base (one of five closely related ring-shaped molecules); and a phosphate group (a tiny cluster made up of a phosphorus atom surrounded by four oxygen atoms). RNA consists of a long chain of single nucleotides, while in DNA two such chains link together and twist into the famed “double helix” structure.

Finally (as we’ll see in the next chapter), arrays of elongated hydrocarbon molecules called lipids, including a wide variety of fats and oils, coalesce in every cell to form membranes, store energy, and perform other critical functions.

The most enticing aspect of Stanley Miller’s experiment and the discoveries of subsequent prebiotic researchers was that they synthesized components (or at least close relatives) of all four groups—carbohydrates, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipid membranes. No wonder so many researchers were optimistic that an understanding of life’s emergence was at hand.

But this molecular catalog of success ignores a puzzling part of the prebiotic synthesis story. For every useful molecule produced, many

other species with no obvious biological function complicate the picture. Take sugar molecules, for example. All living cells rely on two kinds of 5-carbon sugar molecules: ribose and deoxyribose. Sure enough, several plausible prebiotic synthesis pathways yield small amounts of these essential sugars. But for every one of these molecules produced, many other 5-carbon sugar species also appear—xylose, arabinose, and lyxose, for example. Adding to this chemical complexity is a bewildering array of more than 100 3-, 4-, 6-, and 7-carbon sugars, in chain, branching, and ring structures—of which life uses only a small handful.

As if that weren’t enough of a problem, life is even choosier about its molecules. Many organic molecules, including ribose and deoxyribose, come in mirror-image pairs. These left- and right-handed varieties are in most respects chemically identical. They possess the same chemical formula and many of the same physical properties—identical melting and boiling points, for example. But they differ in their shapes, just like your left and right hands. Laboratory synthesis usually yields equal amounts of left- and right-handed sugars, but finicky life employs only the right-handed sugars, never the left.

Given the disparity between the rich variety of prebiotic molecules and the apparent paucity of biomolecules, is it possible that we’re fooling ourselves? Might the earliest life-forms have used a more diverse suite of organic molecules and a different repertoire of biochemical pathways? It turns out that living cells hold clues that are now being teased out by the remarkable field of molecular phylogeny.

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENY AND THE “LAST COMMON ANCESTOR”

The complete chemical arsenal of each living species is recorded in its unique genome, an encoded sequence of millions to billions of DNA “letters,” the base pairs that form the rungs of DNA’s double helical ladder. The four-letter DNA alphabet—A, G, T, and C (for the purines adenine and guanine and the pyrimidines thymine and cytosine)—is sufficient to spell out all the genetic information of any organism. What’s more, all cells share the same mechanism for converting genetic instructions into the proteins that serve in many chemical and structural roles. That’s why genetic engineers can use a simple bacte-

rium, such as E. coli, to synthesize human growth hormone, or insulin, or other valuable pharmaceuticals.

A central assumption of molecular phylogeny is that the genomes we see today evolved over billions of years from earlier ancestral cells, via the gradual mutation of DNA sequences. Comparative examination of many genomes reveals marked similarities, as well as important differences that have inexorably arisen by this slow evolutionary process. Differences among DNA sequences suggest the evolutionary branching; the more dissimilar the sequences of two species, the longer ago they are likely to have split from a common ancestor. DNA sequences that show little variation among many diverse species (so-called highly conserved sequences) are more likely to represent ancient, essential biochemical traits.

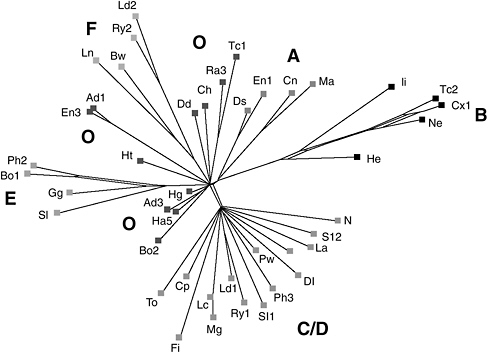

The power and promise of phylogenetic analysis is epitomized in a remarkable recent study of early English literature. University of Cambridge biochemists Adrian Barbrook and Christopher Howe teamed with British literary scholars to analyze 58 different fifteenth-century manuscript copies of the Wife of Bath’s Prologue from Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. No copy of the late fourteenth-century original in Chaucer’s hand is known, and significant variations among the many early hand-copied sources raise doubts regarding the author’s original text.

For their Chaucer analysis, Barbrook, Howe, and co-workers employed the same computer techniques used by evolutionary biologists to identify the most primitive organisms. They entered each of the Prologue’s 850 lines from all 58 versions into the computer and searched for textual similarities and differences. Features common to most sources presumably reflected the original text, while variations that arose from copying errors or deliberate changes were used to construct a kind of genealogy of the manuscripts.

The British team found that 44 manuscripts fell neatly into 5 groups, evidently descended from 5 different copying sources. (The remaining 14 showed more extreme deviations and were eliminated from consideration.) One group of 11 manuscripts proved crucial, for it lay much closer to the presumed original than the others. Surprisingly, these 11 texts had received comparatively little study from literary scholars. “In time, this may lead editors to produce a radically different text of The Canterbury Tales,” Barbrook and colleagues concluded.

Computer-aided analysis of several dozen hand-copied manuscripts of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales points to several distinct groups of texts, denoted by letters. Each manuscript is represented as a line on this diagram; the length of the lines corresponds to the amount of deviation from a presumed primary source. Of these, the groups marked “O” appear to be closest to Chaucer’s lost original (after Barbrook et al., 1998).

Molecular phylogenists adopt the same analytical approach. Their “texts” consist of strands of genetic molecules—DNA or its close cousin, RNA—with long sequences of the genetic letters. Thanks to new, rapid sequencing techniques, numerous genomes have been documented, including more than a hundred genomes of various microbes. Phylogenists use powerful computer algorithms to compare their genetic texts.

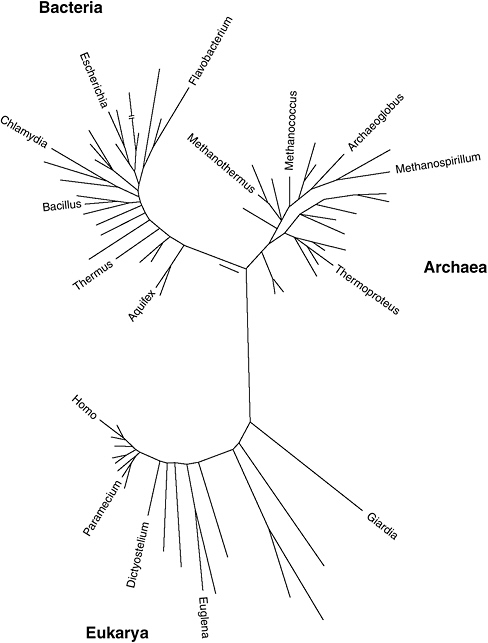

The universally acknowledged pioneer of molecular phylogeny is University of Illinois geneticist Carl Woese, a shy and retiring maverick who had to wait many years for widespread scientific acceptance of his ideas. In a landmark 1977 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: The primary kingdoms,” Woese and Illinois colleague George Fox uprooted what had become the firmly established tree of life. Prior

to the “Woesian revolution,” most biologists recognized five kingdoms of living organisms: animals, plants, fungi, protoctists (complex single-celled organisms with a membrane-bounded nucleus), and bacteria (metabolically diverse organisms that lack a nucleus). Based on his laborious phylogenetic analyses (which were much more difficult in the 1970s than they are today), Woese realized that animals, plants, fungi, and eukaryotes are remarkably similar in their biochemical characteristics and so constitute just one domain of life, the Eukarya. Prokaryotes, on the other hand, displayed astonishing chemical diversity and fell into two distinct kingdoms, which he called Bacteria and Archaea. Bacteria were well known for their role in causing disease, but the Archaea, that as prokaryotes resemble other bacteria in many ways, constituted an unrecognized group of microbes. So contentious was this view of life that it took almost two decades to gain general acceptance.

In retrospect, the lateness of Woese’s discovery should not seem too surprising. Most species in the two microbial kingdoms, Bacteria and Archaea, occur as nondescript microscopic spheres or rods that are virtually impossible to distinguish, even with sophisticated chemical and physiological tests. Consequently, previous workers lumped them all together. Only after the application of molecular phylogeny did the profound differences become obvious.

Woese’s initial intention was to unravel aspects of evolution—to establish a top-down family tree of life and infer the complex history of branchings from parent to daughter species. This evolutionary pursuit led quickly to insights regarding the nature of the last common ancestor. He proposed, for example, that Archaea and Bacteria arose long before Eukarya.

Other discoveries followed. Many of the most primitive microbes are extremophiles that thrive at elevated temperature. To many researchers, Woese’s discoveries thus lent credence to the idea of a deep, hot emergence of life. Other scientists, however, quickly took issue with that conclusion. Deep microbes might well have been the only survivors following a massive asteroid impact and thus, by default, became the last common ancestors of life on Earth today. But those heat-loving microbes might well have evolved from strains of earlier, surface-dwelling cells.

Recent studies point to other intriguing possible characteristics of the presumed last common ancestor. For example, many of the most primitive Archaea are autotrophs, organisms that synthesize their own

Carl Woese compared the genetic sequence of many different organisms, especially microbes, to construct a phylogenetic tree of life. He found three distinct branches of life, including the previously unrecognized Archaea. The majority of the most deeply rooted organisms are extremophiles living at high temperature (after Pace, 1997).

biomolecules. However, many origin specialists, Stanley Miller and his colleagues among them, have long argued that the first cells must have been heterotrophs, which scavenge molecules from their environment. Once again, the controversy cannot be resolved by phylogenetic studies, for deep-dwelling autotrophs that evolved from surface heterotrophs might have been the sole survivors of a globe-sterilizing event.

Additional complexity arises from the tendency of microbes to swap sections of DNA. Remarkably, throughout the history of life, cells have picked up chunks of DNA from completely different species to form new, hybrid genomes. Thus the idealized view of an unbroken branching history of DNA evolution from parent to daughter is invalid. There is no single “last common ancestor.”

In spite of these uncertainties, molecular phylogeny provides invaluable information regarding the shared biochemical heritage of all cells—information that continues to inform origins research. Two observations stand out. First, all cells employ RNA to carry genetic information and assemble proteins. The earliest genetic mechanism thus points to an ancient “RNA World” (see Chapter 16). Second, at the heart of every cell’s chemical machinery lies a simple metabolic strategy called the citric acid cycle, which is powered by simple chemical reactions. Any successful model of life’s emergence must thus account for the origin of this cycle (see Chapter 15).

An important conclusion from these phylogenetic studies is that Earth’s earliest cells were not so different from those of today. They probably relied on similar, though simpler, biochemical pathways. Those similarities provide a clear focus for experimental studies of emergent biochemistry.

![]()

The greatest challenge in understanding life’s emergence lies in finding mechanisms by which just the right combination of smaller molecules was selected, concentrated, and organized into the larger macromolecular structures like RNA and in self-replicating cycles of molecules like the citric acid cycle. But regardless of how much organic stuff was made, the primordial ocean—with an estimated volume greater than 320 cubic miles—formed a hopelessly dilute soup in which it would have been all but impossible for the right combination

of molecules to bump into one another and make anything useful in the chemical path to life. Complex emergent systems require a minimum concentration of interacting agents. Many scientists have therefore settled on an obvious solution: Focus on surfaces, where molecules tend to concentrate.

Interesting chemistry takes place on surfaces where two different materials meet and molecules often congregate. The surface of the ocean, where air meets water, is one such promising place. Perhaps a primordial “oil slick” concentrated organic molecules. Evaporating tidal pools, where rock and water meet and cycles of evaporation concentrate stranded chemicals, represent another appealing location for origin-of-life chemistry. Deep within the crust and in hydrothermal volcanic zones, mineral surfaces may have played a similar role, selecting, concentrating, and organizing molecules on their periodic, crystalline surfaces. Whatever the mise-en-scène, a surface seems a logical site for life’s origin.

But just suppose a collection of organic molecules could organize themselves in such a way that they provided their own surface? Now that would be a trick worth learning!