Genesis: The Scientific Quest for Life's Origin (2005)

Chapter: 13 Left and Right

13

Left and Right

Assemblage on corresponding crystal faces of enantiomorphic pairs of crystals, such as right-hand and left-hand quartz crystals, would provide us with a most simple and direct possibility of localized separate assemblage of right- and left-hand asymmetric molecules.

Victor M. Goldschmidt, 1952

Prebiotic processes produced a bewildering diversity of molecules. Some of those organic molecules were poised to serve as the essential starting materials of life—amino acids, sugars, lipids, and more. But most of that molecular jumble played no role whatsoever in the dawn of life. The emergence of concentrated suites of just the right mix remains a central puzzle in origin-of-life research.

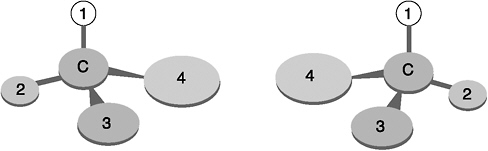

One of the stages of life’s emergence—an early and confounding one at that—must have been the incorporation of handedness. Many of the most important biomolecules, amino acids and sugars included, come in mirror-image pairs: something like your two hands, which have the exact same structure, but can’t be exactly superimposed. In the same way, pairs of these so-called chiral molecules have the exact same composition and structure, and many of the same physical properties, but they are mirror images of each other.

Virtually all known prebiotic synthesis pathways produce chiral molecules in 50:50 mixtures. No obvious inherent reason exists why left or right should be preferred. And yet living cells display the most exquisite selectivity, choosing right-handed sugars over left and left-handed amino acids over right. In spite of a century and a half of study, the origin of this biochemical “homochirality” remains a central mystery of life’s emergence.

THE HANDEDNESS OF LIFE

Molecular chirality arises from a common circumstance of organic molecules. In many molecules, one carbon atom forms four bonds to four different groups of atoms. The amino acid alanine, for example, has a central carbon atom linked to one NH2 molecule (an amino group), one COOH molecule (a carboxyl group), one CH3 molecule (a methyl group), and one lone hydrogen atom. If you orient the hydrogen atom up and look down on the molecule, there are two ways to arrange the remaining three components. So-called “right-handed” or D-alanine has a clockwise arrangement of carboxyl–amine–methyl groups. Chemists employ the letter “D” after the Greek “dextro” for “right” (though the designation of molecular “right” vs. “left” is a completely arbitrary convention.) Alternatively, “left-handed” or L-alanine features a clockwise arrangement of amine–carboxyl–methyl groups. In this case the “L” comes from the Greek “levo,” for “left.”

For reasons that are still not well understood, life selects L-amino acids and D-sugars almost exclusively over D-amino acids and L-sugars. One critical consequence of this selection is that our cells often respond very differently to other kinds of chiral molecules. The familiar flavoring limonene, for example, tastes like lemons in its right-handed form, but like oranges in the left-handed variant. More sinister is the behavior of the infamous drug thalidomide: The left-handed form cures morning sickness, while the right-handed form induces birth defects. Consequently, the Food and Drug Administration demands

Many biomolecules occur in both left-handed and right-handed variants, which are mirror images of each other. This situation arises when a central carbon atom is linked to four different groups of atoms—groups that can be arranged clockwise or counterclockwise.

chiral purity in many pharmaceuticals—a difficult processing step that adds more than $100 billion annually to our drug costs.

Chirality is an essential, diagnostic characteristic of cellular life. But how did this selectivity emerge in the seemingly random prebiotic world? A dozen theories, from the mundane to the exotic, have been proposed, but all ideas fall into one of two general categories.

Some experts suspect that prebiotic synthesis was an inherently asymmetrical process, leading to an inevitable global excess of L- over D-amino acids on the prebiotic Earth. More than a century and a half ago, Louis Pasteur demonstrated that left- and right-handed crystals cause polarized light to be rotated in opposite directions. Conversely, the orientation of polarized light shining on a chemical-rich environment might influence the relative proportions of left- versus right-handed molecules, either by selective synthesis of L-amino acids, or by selective breakdown of D-amino acids. Though the effect is generally small, this kind of chiral-selective process might conceivably have occurred in deep space near a rapidly rotating neutron star, or perhaps on Earth’s surface as the result of polarized sunlight reflected off the ocean surface. No one knows for sure what hundreds of millions of years of such processing might yield.

Other physicists echo this theme, but posit that asymmetric synthesis resulted from so-called parity violations that occur during radioactive beta decay. In physics, the parity principle states that physical processes appear exactly the same when viewed in a mirror. Beta decay, which occurs when an unstable radioactive atom loses an electron (or a positron) in the process of becoming a stable atom, is the only known physical event that violates this parity principle. Beta-decay events produce polarized radiation of only one handedness, and this chiral radiation, in turn, could have enhanced the synthesis of L -versus D-amino acids. One problem with these asymmetric processes is that they seem to yield only the slightest excess of one handedness over the other—generally less than a minuscule fraction of 1 percent. Such minute effects hardly seem sufficient to tip the global balance toward L-amino acids or D-sugars.

LOCAL SYMMETRY BREAKING

Many origin-of-life researchers (myself included) argue that chiral selectivity more likely occurred as the result of an asymmetric local, as

opposed to global, physical environment on Earth. After all, the emergence of life consisted of a series of chemical events, each of which occurred at a specific place and a specific time. It is very possible that those emergent steps were repeated countless millions of times across the globe, but each individual emergent event was local: It occurred at specific location with specific molecules. Consequently, if the local environment where a reaction occurred was strongly chiral, then chiral molecules might have emerged.

The chemical process of life’s origin is in some respects like the formation of a crystal. In life, as in crystals, two essential and largely independent steps are necessary. The first step in crystal formation, nucleation, requires the precise organization of a relatively small number of atoms or molecules into a “seed.” This seed might by chance have either a D or L character. Then comes growth, as the original seed provides a template for the ordered assembly of more atoms and molecules. Each step in the chemical origin of life must also have required nucleation, followed by growth.

In life, as in crystal formation, these two stages usually proceed at very different rates. Nucleation may take place with ease, while growth is slow. Such a situation leads to the myriad microscopic crystallites that give colorful agates and frosted glass their distinctive translucent optical properties. If, on the other hand, nucleation is rare while growth is rapid, then a single large crystal may form.

Since life is vastly more complex than any crystal, it is reasonable to think that nucleation—the self-organization of molecules into a replicating entity—is relatively rare, perhaps even a singular event in Earth’s history (though that is by no means a certainty). But, once formed, this protolife must have grown rapidly, in the process consuming every available molecular feedstock and frustrating further origin events. If that life-form was by chance homochiral, D or L, then that handedness would be passed on to subsequent generations. All it takes is an initial local chiral environment.

We now realize that such local environments abounded on the prebiotic Earth. Indeed, every chiral molecule is itself a tiny local chiral environment that might select other molecules of similar handedness. The pioneering chirality studies of Louis Pasteur relied on this characteristic: When he evaporated a 50:50 solution of D- and L-tartaric acid, the mixture spontaneously divided into pure D and pure L crystals. Such

a circumstance arises because D-D or L-L pairs of tartaric acid molecules happen to fit together more easily than D-L pairs.

Might prebiotic organic molecules have displayed the same behavior? Evidence is still spotty, but a few experiments do reveal a strong tendency for chiral self-selection in certain polymers. The Swiss chemist Albert Eschenmoser, who explored the stabilities of more than a dozen variants of RNA with modified sugar-phosphate backbones, has found that some (but not all) of these molecular chains grow spontaneously with greater than 90 percent chiral purity. Perhaps prebiotic polymers became homochiral by a similar self-selection process.

One caveat: In a dilute, complex primordial broth, the chances of linking together any two types of molecule, much less two useful monomers of the same handedness, would have been exceedingly small. That’s why James Ferris, Leslie Orgel, Graham Cairns-Smith, and others have resorted to mineral surfaces, which induce polymerization by concentrating and aligning desirable molecules. But some mineral surfaces have an added advantage. Every rock, every grain of sand or particle of silt also has the potential to offer chiral environments, in the form of asymmetric mineral surfaces. Left- and right-handed mineral surfaces might provide the perfect solution for concentrating and separating a 50:50 mixture of L and D molecules.

Minerals often display beautiful crystal faces, which might have provided ideal templates for the assembly of life’s molecules. A few minerals, most notably quartz (the commonest grains of beach sand), occur in both right-handed and left-handed structural variants. The quartz structure features helices of atoms that in some crystals spiral to the left and in other crystals to the right. Every grain of beach sand thus provides a chiral environment.

But even though the vast majority of minerals are “centrosymmet-ric,” and thus not inherently handed, their crystals commonly feature pairs of faces whose surface structures are mirror images of each other. Like quartz, these chiral surfaces have arrangements of atoms that are ideally suited to select and concentrate L versus D molecules, such as amino acids or sugars.

Natural left- and right-handed surfaces occur in roughly equal numbers, so there’s not much chance of chiral selection occurring on a global scale. But, once again, here’s the key: The chemical origin of life was not a global event. The first common ancestor—the precursor to

The common mineral quartz forms both left-handed and right-handed crystals.

all of the varied life-forms we see on Earth today—arose as a bundle of self-replicating chemicals at a specific place and time. Once that chiral system began making copies of itself, the handedness of life was fixed. To many experts in the field, the choice of L- versus D-amino acids seems to have been a one-time, chance event, and that scenario points to a simple mineralogical mechanism for chiral selection.

CHIRAL MINERAL SURFACES

As a mineralogist for more than a quarter of a century, I love the idea that crystals may have played a central role in life’s beginnings. For a time, the question of origins took me away from minerals, but they have called me back to some of the most delightful experiments of my career.

The chirality problem represents a particularly puzzling aspect of the more general question of molecular selection, but it’s also an as-

pect that can be studied with well-controlled experiments. We know that prebiotic synthesis processes yield huge numbers of different molecules, of which life uses relatively few. It would be impossible to study that full range of prebiotic products in one experiment. But using pairs of chiral molecules makes things a lot easier: Because all known prebiotic syntheses result in equal amounts of left- and right-handed molecules, it’s relatively easy to design an experiment that starts with a 50:50 mix and looks for environments that separate left from right. If we can discover the processes by which handed molecules were selected and concentrated, then there’s hope that we can solve the more general selection problem as well.

For most of the twentieth century, scientists have recognized the power of minerals to select molecules—processes in which one kind of molecule sticks more strongly to a surface than another. If two molecules differ significantly in size and shape, then such selection is easy to comprehend; it’s just a matter of which molecule fits best. But selection between two mirror-image molecules is more difficult. Such pairs of molecules are chemically identical, so each type of molecule forms exactly the same kinds of bonds with the mineral surface. The only way for chiral selection to occur is for the molecule to form three separate points of attachment, and those three bonds can’t be in a straight line. You’ve experienced this kind of selection process if you’ve ever gone bowling. The ball has three holes, for your thumb and second and third fingers. A left-handed bowler can’t use a right-handed ball and vice versa, because the three holes aren’t in a line.

By the 1930s, scientists in Greece and in Japan had applied these ideas and tried separating left- and right-handed molecules by pouring D- and L-solutions over left- or right-handed quartz. During the next half-century, a dozen similar experiments were attempted. The basic idea was sound: Different-handed molecules do have the potential to stick selectively to different-handed surfaces. Nevertheless, these early experiments were flawed. In an effort to maximize the surface area of interaction, and thus the magnitude of the desired effect, the scientists ground their beautiful quartz crystals into fine powder. Powdering increases the surface area of a peanut-sized crystal a thousand times or more, but it destroys the flat crystal surfaces that might promote selection. A powder displays every possible crystal surface simultaneously. Some of these surfaces may very well select L-amino acids with great efficiency, but surfaces with a different exposed atomic

structure might just as likely select D-amino acids. Even if an experiment revealed a small preference for L or D molecules, there would be no hope at all of determining which crystal surface was doing the selecting.

I decided to try a different approach.

![]()

Big crystals are the key—fist-sized crystals with fine flat faces. That’s the only way to understand the atomic-scale interaction between molecule and crystal. But what mineral fits the bill?

My crystals had to be big because a layer of molecules adsorbed onto a surface an inch square weighs at most a few billionths of a gram—a daunting analytical challenge. To measure that effect, I had to find crystals with faces at least a few square inches in area. Big crystals of most minerals tend to be astronomically expensive, thanks to the voracious appetite of mineral collectors; so I had to find a common rock-forming mineral that collectors don’t covet. As an added benefit, the commonest minerals are also likely to be the most relevant to origin scenarios. Most important, the crystals had to possess faces with surface structures that lack mirror symmetry. Only a chiral face could accomplish the chiral selection task.

I thumbed through my favorite mineralogy book, a frayed, dogeared copy of Edward Dana’s A Textbook of Mineralogy, purchased at the American Museum of Natural History when I was 14. Classic line drawings of crystal forms decorate almost every page. The vast majority of crystal faces, I realized, aren’t chiral. Many of the commonest minerals—garnet, olivine, mica, pyrite—won’t do.

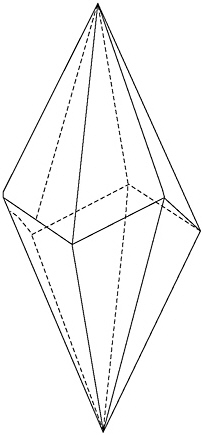

Then I turned to page 512—calcite, an abundant mineral and the one most closely associated with life. Calcite is the mineral of clamshells and snail shells, of pearls and coral. Lo and behold, its commonest crystal faces are chiral. Most calcite crystals feature a graceful, six-sided, pointed form with the fancy scientific name of scalenohedron. Everybody in the business calls it a dogtooth.

A quick search of eBay confirmed that dogtooth calcite crystals are both common and cheap. I bid on three pretty specimens from the then thriving (but now defunct) Elmwood lead-zinc mine outside Carthage, Tennessee. A week and $40 later I had the beginnings of what

The commonest crystal shape of the mineral calcite is the so-called “dogtooth.” All 12 faces of this form are chiral.

has become a sizable calcite crystal collection. Now to design an experiment.

![]()

I wanted to find out whether chiral crystal surfaces would selectively attract chiral molecules. I had fist-sized calcite crystals with left- and right-handed faces, and I had D- and L-amino acids. Would D- or L-amino acids attach themselves preferentially to left- or right-handed calcite faces?

Seventy years of false claims and ambiguous results had set the bar high; a casual, sloppy experiment wouldn’t do. I knew that many previous authors had started with concentrated D- or L-molecules, and then looked for a difference in behavior as those molecules interacted with a chiral crystal (usually quartz). That experimental path was fraught with

difficulties, since every nook and cranny of the environment is already contaminated with life’s excess L-amino acids and excess D-sugars. If you look for a chiral effect, you’re probably going to find a chiral effect.

Instead, I prepared a 50:50 solution of D- and L-aspartic acid, an amino acid known to have special affinity for calcite in the proteins that add strength and resiliency to all sorts of shells. The idea was to expose both left- and right-handed calcite faces to this mixed solution, and then see which molecules stuck to which face. If crystal faces really do have the ability to select chiral molecules, then left- and right-handed calcite faces should attract equal and opposite excesses of L- and D-molecules.

The experiment sounded easy in principle, but it took months to get right. First we had to figure out a way to clean the crystals, which had been handled by dozens of people, from Tennessee miners to Geophysical Lab scientists. The slightest contamination—a fingerprint, a breath, even a speck of dust—could skew our results. We settled on a procedure of repeatedly washing each crystal in a sequence of strong solvents.

In the first failed round of experiments, postdoc Tim Filley (now a professor at Purdue) and I glued little plastic reservoirs directly onto the calcite crystal faces in hopes of minimizing contamination from dust, bacteria, and other chiral influences in the air. After some practice, we got the little plastic pieces to stick to the smooth calcite surfaces. What we hadn’t realized is that our epoxy glue and our plastic containers were absolutely loaded with chiral molecules, which are part of the plastic-making process. Our careful procedure introduced far more chiral contamination than the atmosphere ever could.

Simple experiments are usually best, so I resorted to what seemed like an almost childish approach. I poured the 50:50 aspartic acid solution into glass beakers and just dunked the lustrous fist-sized calcite crystals into the liquid. Twenty-four hours seemed like a good amount of time to let the crystals soak. I came back the next day, removed the crystals, washed them off quickly in pure water, and then ever so carefully extracted the attached molecules from the crystal surfaces. It was an easy task, because calcite dissolves readily in dilute hydrochloric acid. I held a crystal in my gloved left hand and oriented one face parallel to the bench top. With my right hand, I used a long dropper to cover that face with a thin puddle of acid. We were fortunate that water beads strongly on calcite, so it was relatively easy to keep the acid from

spilling over the sides. After about 20 seconds, I sucked the acid back up into the dropper and emptied it into a waiting vial. We knew that any attached molecules would have been stripped off along with the outer layers of calcite.

Face by face, I applied the acid wash to each of four crystals—more than 20 surfaces in all. Most of these faces were left- or right-handed, but a few were flat, fracture surfaces—the natural breakage planes of the crystal—that are not chiral at all. Those faces would serve as a control on our methods, for they should show no preference for D-or L-amino acids. After an hour and a half of concentrated effort, we had 23 vials in hand. Would they show the desired effect?

In spite of the hassles with contamination, generating the amino acid samples turned out to be the easiest experimental task by far. The real trick, mastered by only a handful of analytical chemists in the world, was to determine whether the calcite crystal faces had preferentially selected D- or L-aspartic acid.

Tim Filley is an expert at organic chemical analysis, so we were confident that we could do the work ourselves. We had an adequate gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer, the analytical machine of choice; we had a chiral chromatographic column that should separate D- from L-aspartic acid; and we had a well-documented procedure for preparing our samples prior to injecting them into the GCMS. The setup took some time, but the methods seemed straightforward.

After a lot of practice with aspartic acid standards in different D:L ratios and different concentrations, we were ready to try the real thing. Our first analyses took place just before Christmas 1999.

GCMS affords a kind of rapid (if not instantaneous) gratification, because the ratio of two compounds, such as D- and L-aspartic acid, corresponds to the areas of two peaks that appear side by side on a graph. Joined by Tim’s wife, Rose, who is also a skilled analytical chemist, we injected our first sample and waited. It took the better part of 20 minutes for the molecules to work their way through the 50-meter-long coiled chiral column, which was packed with chemicals that slow down L-amino acids slightly more than D. D-aspartic acid passed through the column about 20 seconds faster than L-aspartic acid. The first peak showed up sharp and clear—plenty of D-aspartic acid molecules there. The next 20 seconds seemed to take a lot longer than any 20 normal seconds should, but the second peak, representing L-aspartic acid, appeared on schedule. And it was clearly bigger—at a guess,

more than 10 percent bigger. We allowed the machine to run just a few minutes longer, to make sure there weren’t any obvious contaminants, and then stopped to let the computer calculate the peak areas.

The actual ratio turned out to be closer to a 5-percent excess of L, but it was a tantalizing result that clearly pointed to chiral selection. We decided to run the same sample a second time, just to be sure. Twenty minutes later, the pair of peaks appeared again, but this time we saw no more than a 1-percent excess of L, not enough to be sure the effect was real. The average value was a 3-percent excess, while our experimental error was evidently close to ±2 percent. Tim suggested that we run a couple of more standards to be sure the machine was giving us clean peaks.

We were off and running, with 22 more samples, each to be prepared and run in duplicate, plus standards after every few sample injections. Given the prep time, it took more than two hours to test each sample or standard. We started running in three overlapping shifts. With two small girls, Rose was always up early and did the first few injections. Tim and I usually couldn’t stay away, so we’d take over in the morning and keep things running through the evening and into the wee hours. For the first couple of days, we were there 18 or more hours at a stretch, running sample after sample, eagerly watching the screen as the pair of peaks appeared 20 minutes into each run. It was addictive and exhausting, like a slow-motion video game.

So it went: Run a few samples with tantalizing results, then more standards. One encouraging sample suggested a 4-percent excess of D-aspartic acid—a critical result, since L contamination, the life sign, was everywhere, but an excess of D could come about only through crystal selection. Still, the results weren’t consistent. What was even worse, the peak shapes began to broaden and degrade after only about 25 injections. Broad peaks overlap, making analysis of the D:L ratio all but impossible.

We called the supplier of the chiral column to complain—a new $500 column like ours should have lasted for hundreds of runs, not just 25. They suggested that we bake out the column to make sure that large, unwanted molecules hadn’t contaminated it. We had been turning off the machine a few minutes after we saw the aspartic acid peaks, because we were eager to do the analyses as fast as possible. Perhaps other slower molecules hadn’t made it all the way through the column and were gumming up the system.

After the prescribed treatment, the column worked better for a few injections, but soon the peak shapes were worse than ever. We called the company again.

“What kind of samples are you running?” they asked.

“Just aspartic acid,” Tim said.

“Are you sure there’s nothing else in the samples?” they responded.

“Well, maybe a little bit of dissolved calcite; it’s just calcium carbonate.”

That was it. The company rep told us that the mineral residue had quickly degraded our column, making it useless for further work. They generously offered to send us another for free (probably suspecting that we’d be going through a great many $500 columns in the coming months).

So now we’d have to execute an additional chemical step to remove the calcium carbonate with acid before injection. We weren’t happy about that, because each additional treatment of the samples increased the chance of contamination.

We kept trying, but those first experiments were just too flaky. Lots of L excesses of a few percent, one or two D excesses, but nothing really systematic. What’s more, some of the L excesses came from the fracture surfaces, which should have had no effect, while the right- and left-handed calcite faces gave inconsistent results at best.

We had spent months at the project with nothing to show for it but a lot of experience under our belts. In the spring of 2000, Tim’s postdoc was nearly up. He and Rose were looking forward to setting up a new home in Indiana. I had to make a decision whether, and if so how, to continue.

![]()

I decided to give it another shot. One thing was absolutely clear: The experiments had to be performed in ultraclean facilities, with every possible precaution against contamination. My colleagues at our sister lab, the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (DTM for short), maintain a chemical clean lab at our Northwest Washington campus for isotope and trace-element work, and they generously let me use one of their high-tech chemical hoods for a few months.

In May of 2000, I hauled box upon box of chemicals, glassware, and crystals to the second-floor clean lab of DTM’s venerable experi-

ment building. The sparkling, well-lit labs could be entered only through a small glassed-in vestibule, where the transition to clean-room protocols took place. I removed my shoes and slipped into a pair of pale-blue booties, white coveralls, hood, respirator mask, and latex gloves. The protective gear wasn’t uncomfortable, but it took a bit of getting used to.

After organizing my supplies, I began the experiment. Leaving nothing to chance, I treated the thrice-washed crystals with extra care, used the highest-purity amino acids, ultra-pure water (at $40 per gallon!), and freshly baked glassware. Every step was carried out in a chemical hood, a glass-enclosed volume about 4 feet wide, 2 feet deep, and 3 feet high—plenty of room for my beakers. My hood was maintained with positive pressure to prevent outside air from entering the enclosed area.

The experiments were conducted almost exactly as before. First, soak four crystals for 24 hours in the 50:50 amino acid bath. This time I made sure that the pH of the solution remained close to 8, a value ensuring that the calcite would not start to dissolve. Then, after a day of soaking, I repeated the now-familiar wash process, applying acid to each crystal, face by face. The day’s work produced 23 small glass vials of acid extract. Over the next two days, I repeated the entire experiment two more times to be absolutely certain.

A week’s work yielded 69 vials of aspartic acid solution washed from crystal faces, plus several vials with individual samples of each day’s aspartic acid solution, of the pure water, and of the acid wash. I wanted samples of everything, in case I had to track down contaminants. More than 75 sample vials needed to be processed, each to be analyzed at least 3 times. Two-hundred-plus amino acid analyses is a huge job, and the Geophysical Lab facilities were not up to it. So for that crucial, final step I headed downtown, hat in hand, to George Washington University, to see geochemist Glenn Goodfriend, a former colleague at the Geophysical Laboratory.

Success in a scientific career can be measured in many ways. Some scientists crave admiration and respect from their peers. Others prize a flexible job that gives them the freedom to pursue any line of research. And for many researchers, the quiet exuberance of doing good science is the prime measure of a happy and successful career. By all these measures, Goodfriend was one of the most successful scientists I’d ever known.

At the agreed-upon late-morning hour, I arrived at his modest office in the basement of Lisner Hall, home of the Geology Department. Glenn was a research professor, his work sustained almost entirely by a succession of two- and three-year grants from the National Science Foundation. Few scientists have the stature and stamina to survive like that for long, but Glenn was a master with more than a decade of steady funding.

“Hi, Bob!” he said, with his usual big smile, his thick black mustache and curly black hair making him seem younger than his years. (“It comes from drinking lots of good red wine,” he’d say.) Piles of manuscripts and journals covered most of his desk and surrounding tables; banks of neatly labeled filing cabinets hinted that he had the upper hand on entropy. Glenn leaned back in his chair, hands behind his head—a characteristic gesture I’d soon come to learn. “What’s up?”

I described the chirality experiments and their implications for origins research in as sexy a way as I could. Glenn nodded often, but his smile slowly faded. When I had finished, he launched into an intimidating list of his own amino acid projects already underway.

Glenn’s research exploited the fact that although almost all of life’s amino acids are left-handed, as soon as an organism dies, a slow, inexorable process called racemization—the random flipping of molecules from L to D and vice versa—begins. Eventually, after a few tens of thousands of years, an organism’s amino acids will have completely randomized to a 50:50 mixture. This tendency for the D:L ratio of amino acids to change over time provides a powerful dating technique: The older the shell or bone, the closer its amino acids will be to a 50:50 mix. Other factors—notably the average water temperature, the acidity, and the salinity—also affect the rate of racemization; the D:L ratio in a fossil can thus provide evidence for changes in ancient environments. Glenn was one of the world’s experts in determining that crucial ratio, so scientists from all over asked for his help. In one ongoing collaboration, he determined the ages of fossil eggshells from Australia, to help understand long-term changes in the continent’s vegetation. Another project used clam shells to measure recent changes in the salinity of the Venetian Lagoon. He also was studying amino acids in fossil shells from the Baja Peninsula of Mexico to deduce patterns of climate change.

But his biggest and boldest effort was his long-term collaboration with Harvard paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould on the evolution of

Cerion, a beautiful little Bahamian land snail. Glenn had helped to collect countless thousands of these inch-long shells from deep pits dug into remote sand dunes. The major part of the collection was exhumed from a deserted stretch of Long Island in the Bahamas. Glenn’s Cerion specimens displayed remarkable variations, even though all were members of a single species. Some shells were elongated, while others were almost round; some richly decorated, others almost smooth. These and several dozen other morphological characteristics provided Gould with a perfect species to test his provocative theories of evolutionary change. Glenn’s job was to provide the critical dating by analyzing D:L ratios from thousands of individual shells. Once supplied with enough differently shaped shells, their ages, and the DNA analyses performed by another colleague, Gould hoped to tease out the evolutionary pathways of gradual morphological change. Years, maybe decades, of work lay ahead.

Given these commitments, Glenn was certainly too busy to take on a new project. Yet he was also intrigued. Chiral selection was a new challenge for his analytical system, and he knew a good project when he saw it.

“Looks like it’s about time for lunch!” he said, abruptly changing the subject.

“Let me take you.” I sensed a setup, but I would have done just about anything to secure his help.

“There’s a nice little place a couple of blocks from here. Kinkead’s.” It wasn’t a question.

“Sure, let’s go.”

Kinkead’s specializes in seafood, to which Glenn was deathly allergic; he even had to wear protective gloves when handling his favorite Cerion shells. But Kinkead’s had a great wine list, and Glenn had a passion for good red wines. Glenn ordered glasses of two different wines and extra glasses for each of us, so we could compare and contrast. Some months later, I learned that Kinkead’s was a kind of test; had I balked at the noontime diversion, our collaboration might never have happened.

Evidently I passed. “OK,” he said, and paused. “You’ll have to derivatize the samples, but I’ll do the analyses.” So I would have to do a bit of chemical prep work, but I was in business.

Glenn had to maintain his analytical facility in the same large room as the undergraduate anthropology lab at George Washington. The first

thing you notice on entering is the inordinate number of bones—dozens of human skulls, legs, ribs, and hip bones in wooden trays and glass display cases. A fully mounted human skeleton (lacking only the odd digit and forelimb) presides slack-jawed over the unsettling scene. A long, black-topped table surrounded by two dozen padded stools occupied the center of the 25 × 40-foot space. Glenn had a cramped 3-foot-square chemical hood on one side of the room and his arsenal of state-of-the-art gas chromatographs along the opposite wall, where any undergraduate might inadvertently bump into them. How could anyone work effectively under these conditions, I wondered? And yet one quickly learns to focus only on the diminutive vials and their secrets.

I showed up there mid-morning of the following week to prepare my amino acid samples for analysis. The aspartic acid had to be chemically modified so that the D- and L-amino acids could be separated more efficiently by gas chromatography. The amino acid molecules, which normally dry to a white powder, had to be treated so that they evaporated to a gas at high temperature. Under Glenn’s guidance, I made sure each sample was completely dried down, then added a milliliter of thionyl chloride, an orange-tinged toxic liquid, and tightly capped the vials under a stream of nitrogen gas. Then we cooked the samples, two dozen at a time, in the oven.

I have never watched a scientist more meticulous in his procedures than Glenn, who proved to be one of the most exacting, finicky experimentalists I’d ever met. Like a master chef, he prepared amino acid samples for analysis the same way every time. He heated them at 100°C for one hour in a small, squat oven, instructing me to open the oven door quickly and place the tray of vials on the shelf in one swift gesture. Close the door within 4 seconds to keep the temperature at the proper level. If the temperature dropped even 0.2°C, he recorded it in his lab notebook.

An hour later, to the second, I had to remove the samples from the oven with a similar smooth motion. If I was 10 or 15 seconds late, his mustache would twitch and the discrepancy went into the notebook. One secret to Glenn’s success was his absolute, rigorous reproducible procedures.

Once the rows of vials had cooled, I opened each one, dried them under a vacuum, added a second chemical (trifluoroacetic acid anhydride), sealed the vials, and heated them again for exactly five minutes. At the end of this process, each amino acid sample had been modified

to a volatile form that was ready to analyze. We transferred a small volume from each into glass autosampler vials, loaded up the gas chromatograph, and set it to run overnight.

Glenn and I were paranoid about the potential for unconscious bias. We knew exactly the chiral effects we were looking for—certain faces should select L-molecules and others D-molecules, while the fracture surfaces should display no preference. So I randomly renumbered the samples and Glenn renumbered them again in his own notebook. That way, neither of us would know which sample came from which face until after we’d completed all the analyses and compared numbers. It’s all too easy to see what you want to see in random data. Once the samples were prepared, we had only to wait for the automated machine to do the analyses. Glenn promised to call me the next day with our first results.

“Hi, Bob. Looks like we have some data,” he reported the next afternoon. “Got a pen?” I scribbled down a long list of specimen numbers and D:L ratios. Quite a few of the numbers were close to 1.00—no effect. But there were also several values significantly higher and lower: 0.958, 1.031, 0.965, and other numbers that pointed to a possible chiral effect.

“Of course we’ll have to repeat all these analyses a couple more times,” Glenn added. I was to learn that performing analyses in triplicate (at a minimum) was one of his trademarks.

“What sorts of reproducibility do we have?”

“Looks like about plus-or-minus half a percent. Not bad.” I was amazed. Errors smaller than 1 percent were almost unheard of in this business.

As soon as I had sorted out which analysis went with which face, a clear and compelling story began to emerge from the data. Left-handed calcite faces almost universally displayed D:L ratios a few percent less than 1.00. These faces preferentially retained L-aspartic acid. The right-handed calcite crystal faces displayed an equal and opposite affinity for D-aspartic acid. Equally important, all of the nonchiral fracture surfaces, which served as our experiment’s internal control yielded D:L ratios indistinguishable from 1.00. Glenn’s repeat analyses of each sample over the next week reinforced the story.

We wrote up the results quickly and submitted the short manuscript to the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, with Hat Yoder serving as the sponsoring Academy member. The discovery that

chiral crystal faces of calcite selectively adsorb D- and L-amino acids suggested not only a plausible chiral environment on the early Earth, but also a possible mechanism for making functional biological macromolecules. If adsorbed L-amino acids lined up sequentially on the crystal surface, then they might be poised to link to each other, forming a protein-like polymer of amino acids. Perhaps in this way mineral surfaces selected, organized, and assembled the first homochiral biomolecules.

As we had hoped, a few workers in the origin-of-life community noticed our results. What we had not anticipated was significant interest from chemical engineers engaged in the design and purification of chiral pharmaceuticals. Our work on chiral mineral surfaces had opened the door to a host of possible industrial applications in the $100-billion-a-year chiral drug business.

For our part, Glenn and I saw the aspartic acid study as the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration. Next on the agenda were similar experiments with D- and L-glutamic acid, another amino acid that binds readily to calcite. We also plotted out new experiments with left-and right-handed quartz crystals. As our friendship grew, so did my interest in his other research projects, and he signed up my wife and me as field hands for his next Bahamain field season the following December.

It was during these new experiments that Glenn, uncharacteristically, began to complain of an incessant pain in his jaw. A drug-resistant tooth infection had gradually spread through his mouth and into his sinuses. Worse than the pain, the disease numbed Glenn’s sense of taste. He began to lose weight rapidly. He stopped drinking wine. In March of 2002, the antibiotic Cipro seemed to turn the tide. Glenn rallied and he even agreed to visit a favorite lunch spot, Pizza Paradiso, where for the first time in weeks he managed to eat most of his lunch. We talked optimistically of our December trip to the Bahamas.

Though weakened, Glenn returned to his lab and began to recalibrate the sensitive analytical machines that had sat idle for so long. On March 27th, we enjoyed a brief, sobering visit from Steve Gould, whose magnum opus, On the Structure of Evolutionary Theory, had just appeared in print. Steve talked optimistically about the upcoming fieldwork, but he had just been diagnosed with a fast-spreading cancer and he tired quickly. During much of the visit, he sat in front of piles of his beloved Cerion, picking up one after another,

pointing out unusual features. He kept saying “I need another 20 years. I just need another 20 years.” [Plate 8]

But it was not to be. Stephen Jay Gould died of cancer on May 20th, fewer than two months later.

By the end of May, Glenn’s infection had returned with increased virulence, spreading to his brain, confusing his thoughts. During our last halting conversation, in early October, he fretted about the long hiatus in his research. He spoke eagerly of the December field trip to the Bahamas, as if in another few weeks he’d be well again. In his delirium, he anticipated meeting Steve Gould on the island.

Glenn Goodfriend died on October 15, 2002, at the age of 51. The chance to know and work with him was one of the greatest gifts of my career, and his decline and death one of the saddest events I’ve ever had to experience. For months I was paralyzed by the loss. Asking anyone else to fill Glenn’s shoes seemed disrespectful, like marrying again too soon after the death of a spouse. Colorful crystals lay idle in my lab. More than a hundred vials of amino acids sat unanalyzed. Only gradually, with the help of new collaborators, did the chiral-selection project get back on track.

![]()

Scientists don’t know for certain—and may never know for certain—how life’s homochirality emerged from the random prebiotic milieu, but we have targeted an expanded repertoire of promising local chiral environments. Perhaps life’s molecules self-select for handedness. Or perhaps they spontaneously assemble on chiral mineral surfaces. Whatever the answer, these ideas offer years of opportunities for origin-of-life researchers (and chemical engineers, as well).

What we can say for sure at this stage is that mineral surfaces are remarkably successful at selecting, concentrating, and organizing organic compounds. Thanks to quartz, calcite, and a growing list of other crystals, the mystery of the emergence of organized molecular systems from the complex prebiotic soup seems a lot closer to being solved. It would appear that minerals played a far more central role in the origin of life than previously imagined. Armed with that understanding, chemists, biologists, and geologists are embracing a more integrated approach to one of science’s oldest questions.