Health and Safety Needs of Older Workers (2004)

Chapter: 5 Physical and Cognitive Differences Between Older and Younger Workers

5

Physical and Cognitive Differences Between Older and Younger Workers

Older workers differ from their younger counterparts in a variety of physical/biological, psychological/mental, and social dimensions. In some cases these reflect normative changes of aging (e.g., presbyopia); in others they represent age-dependent increases in the likelihood of developing various abnormal conditions (e.g., coronary artery disease). In some cases these age-related differences (whether normative or pathologic) are disadvantageous to the older workers because their work performance is diminished relative to that of younger workers. For example, older workers are likely to have decreased capacity to sustain heavy physical labor for extended periods. In other cases these age-related differences are disadvan-tageous to older workers because their susceptibility to environmental hazards is increased. For example, Zwerling et al. (1998) reports that poor eyesight and hearing are associated with occupational injuries among older workers. In still other cases, however, changes associated with age may actually enhance capabilities and performance at work. For example, crystallized knowledge (that which has accumulated and is stored, often contrasted with fluid knowledge, which refers to the flexible solution of novel problems) and its positive impact on work is likely to be greater in 50-year-old than 20-year-old workers.

This chapter examines these age-related differences in function, capacity, and vulnerability, investigating the physical, psychological, and social characteristics that distinguish older from younger workers and how they affect differences in function, capacity, and vulnerability.

WELL-BEING OF OLDER WORKERS AND CHANGES WITH AGE

Because of changing workplace environments, job opportunities, and national and regional economic circumstances, maintaining the health and safety of older workers will become increasingly challenging as the number and proportion of older workers continue to grow. It is also likely that there will be important changes in the health status of succeeding cohorts of older workers in ways that may not be fully predictable. For example, overall health status and mortality of successive cohorts of Americans has been improving, but some persons with previously fatal diseases are now surviving to older adulthood and participating in the workforce. Thus, successive cohorts will require special consideration vis-à-vis future workplace threats to older workers. This section briefly reviews population and gerontological concepts relevant to aging, health, and work; delineates the current health and social characteristics of older workers; contrasts these characteristics with those of nonworking age mates; and defines a selected set of important issues related to maintaining optimal health in the face of age-related health changes.

Biological and Gerontological Perspectives on Age-Related Changes and Older Worker Health and Safety

Understanding the health of a given cohort of older workers is aided by important gerontological theory. Particularly important is the life course perspective on aging (Baltes, 1997), also discussed in previous chapters. The life course perspective suggests that a vast array of biological, social, and environmental factors that occur in child and adult development, beginning from conception, all play important roles in the nature and trajectory of aging. This concept acknowledges that the health, function, and survivorship of each older worker cohort will depend in part on exposures and events that occurred in the remote past, in addition to environmental exposures concurrent with aging—the subject of continuing epidemiological research. This trajectory may only be partially overcome by various clinical, social, and environmental interventions. Also, it is axiomatic that there is great interindividual variation in early developmental, genetic, and social factors within a particular birth cohort, and so it is not surprising that there are important differences among persons after 40 to 50 years of age in the capacity for various kinds of workplace activities and challenges. That is not to diminish the role of the social, political, physiochemical, and economic environment facing older workers, but only to point out that many determinants of aging outcomes are already in place.

It is likely that among the most important determinants of health and aging for older workers are the prior work experiences, in turn related to the levels of environmental exposures and hazards as well as the social and

health care opportunities created by work, with their effect on overall socioeconomic status, which is an extremely powerful determinant of the future occurrence of diseases, illnesses or disorders, disability, and death (Adler and Newman, 2002). The intimate association between types of work and the socioeconomic context in which that work takes place makes understanding the health impact of various workplace exposures extremely complex. In addition to prior and current workplace exposures, the trajectory of health and aging will be substantially affected by nonwork-related environmental, physiochemical, and social exposures, such as recreational and other avocational activities, intentional and unintentional injuries, communicable diseases, and unhealthy hygienic behaviors such as tobacco, alcohol, and other substance abuse, careless automobile driving habits, inadequate exercise, unhealthy diets, and many other risk-taking behaviors.

The nature and causes of age-related changes in individuals and populations are complex and in general beyond the scope of this volume. While theories abound, no one has identified a unique cause or biological process that is pure aging. Rather, there are a very large number of age-related changes that involve every bodily system and function to a greater or lesser extent. To the extent that these individual changes have been investigated, age-related change rates in individual bodily organ and system functions do not necessarily track at the same pace. The difference between the mechanisms of aging and disease pathogenesis may also be more apparent than real, with many common causes and opportunities for interdiction. For example, cigarette smoking accelerates the age-related decline in lower extremity function (Bryant and Zarb, 2002) as well as causing lung cancer and coronary heart disease.

Thus, removing or limiting many toxic environmental exposures, particularly the intensive ones that can occur in the workplace, may lead to lower disease rates and improved maintenance of general human function, irrespective of whether the intervention affects aging or disease pathogenesis. Disease phenomena, particularly the large number of chronic conditions that increase in frequency with age, have very important implications for health status and outcomes, including among older workers, but distinguishing a disease from other aging manifestations is often arbitrary or one of degree. Thus, it may be useful to consider aging as age-related change, in reality a large set of important but at least partly malleable processes and functions that are not necessarily biologically obligate or fully predetermined (Arking, 1998).

Observations from the gerontological and geriatric literature enhance the understanding of age-related change. Importantly, this approach avoids attributing older worker performance or function to aging, which may convey an erroneous prospect of immutability or nonpreventability. An example may be lower extremity pain or dysfunction, often related to

degenerative arthritis, an entity that is at least partly preventable and susceptible to treatment and rehabilitation. Many important age-related changes may begin in youth or midlife, which can allow early detection with physiological or other performance testing. Regardless of the causes of these early changes, early physiological abnormalities or behavioral changes can predict later overt dysfunction and disease (Whetstone et al., 2001), allowing the observational and experimental studies of possible interventions. However, not all age-related changes occur in slow, continuous decrements. Not only do acute changes in health and function occur with certain diseases and conditions, such as with injury and acute infectious diseases, but also with the rapid emergence of chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, and stroke (Ferrucci et al., 1996). This highlights the role of clinical disease prevention in deterring what might in populations be seen as age-related functional decline.

It is useful to invoke a phenomenon that is well described in the biology of aging literature: homeostasis (Pedersen, Wan, and Mattson, 2001). This refers to the observation that older human beings (as well as older organisms in other species) may function at a normative level, but when a large stress occurs, whether a disease, illness or disorder, injury, or social occurrence, the ability, ceteris paribus, to return to one’s prior health and functional status is impaired when contrasted with that of younger adults. This may have import for older workers, who may be able to function under usual environmental circumstances, but who have more severe consequences after an acute medical insult, such as a given amount of trauma, a respiratory infection, a toxic exposure, or an unusual climatic condition. Thus, there may be some circumstances where older workers may require more enhanced protection from environmental insults than younger workers, because the consequences of those insults may be greater, and there may be greater premium placed on prevention. When a certain acute insult occurs in the face of existing, if controlled, chronic illness or disorder, the consequences may be more devastating. However, little research has been conducted in this area.

It is important to always consider the role of mental illness or disorder among older persons, including older workers. Mental conditions take a substantial toll on health status, and while major mental illnesses or disorders may have their onset in young adulthood, they often persist into old age. Mental illnesses or disorders such as various psychoses, major depression, bipolar disorder, and substance abuse often have important functional, social, and health consequences and can be related to workplace performance, absenteeism, and the risk workplace-related conditions. Pharmaceutical treatments of some of these conditions may also place some workers at increased risk of work-related injuries, but whether this is a special problem for older workers is uncertain.

Whatever the nature of aging and age-related change, it is axiomatic in gerontology that most general physiological and biological functions in older persons tend to have greater variation than in younger persons, related to greater variation in age-related change, the selective occurrence in subpopulations of specific medical conditions, varied availability of and access to optimal treatments and rehabilitation for these conditions, varied individual capacity to cope with and adapt to these changes and conditions and the nature, compatibility, and adaptability of the social and work environments. It is this variation that provides the basis for the observation that function and performance often do not correlate very well with chronological age (Masuo et al., 1998). Much of this variation may be modified by the social environment outside of work.

Another general characteristic of older populations, including older workers, is the presence of comorbidity (Gijsen et al., 2001; Brody and Grant, 2001). This refers to the distribution and co-occurrence of medical conditions that may affect health status, health risk, and adaptability to the work environment. While some active conditions may limit or preclude employment, many prevalent conditions in older workers are well controlled and do not have a substantial functional impact on worker performance. Comorbidity may, however, affect the use and timing of medical care utilization or encompass treatments that may alter workplace activities, such as somnolent or other psychoactive drugs. However, there has not been very much research on the effects of various workplace exposures on health in the presence of even controlled clinical conditions or their treatments. Also, further evaluation is needed to determine the role of comorbidity as an indicator of increased risk to various workplace exposures, requiring administrative action such as altered job placement.

In addition to acquired comorbidity and the heterogeneity in age-related change is the increasing number of children and young adults with substantial disabilities due to congenital, inherited, or acquired conditions that manifest themselves in childhood or early adulthood. Due to improved medical and rehabilitative care, as well as specialized social support, many more of these individuals are now surviving into late adulthood; some may at certain points be eligible for certain types of productive employment under certain circumstances. How their trajectories of age-related illness or disorders and dysfunction compared to others in the population has not been well characterized and should be one focus of future research in order to determine the suitability for various workplace environments.

However, as noted above, it may be difficult to predict the health and functional status of subsequent cohorts of older populations and older workers. For example, there is emerging evidence that in recent decades each succeeding cohort of older populations, from whom older workers are drawn, have overall better levels of physical and cognitive function than the

prior ones (Manton, Corder, and Stallard, 1997; Schoeni, Freedman, and Wallace, 2001; Freedman, Aykan, and Martin, 2001). The issue is complex and sometimes disputed. However, if true, general, and persistent, this trend could have a positive impact on the net health and function of older workers and their responses to workplace challenges.

Defining Age-Related Health and Functional Changes: Epidemiological Findings and Implications

In general, almost all physiological and mental functions change with increasing age, even if at varying rates and intensities, including internal organ function, physical movement, and sense organ functional characteristics. However, as noted above, the causes for these changes are often unclear, and the consequences for complex activities such as individual job performance are even more uncertain because of personal adaptations and selective forces over time. Nor is it clear how many of the measurable changes are preventable or modifiable, but an increasing literature on intervention studies suggests that some mutability is possible.

When objectively evaluating and measuring the function and performance of older workers, several observations pertinent to assessing age-related physiological and metabolic changes should be considered in order to understand the impact of past or present work exposures on health and functional status:

-

While the rates of age-related change are highly variable by organ, organ system, and anatomic region, in general the slope declines at a greater rate with increasing age. Thus, an important research and clinical problem is that older workers may need more frequent assessments to characterize the impact of work-related exposures. Also, it should be noted that many studies infer age-related change from cross-sectional population measurement, an inference that may not always reflect the reality or trajectory of longitudinal change (for example, see Louis et al., 1986).

-

Age-related changes in workplace performance, particularly using job-related production measures, may not be due to age-related anatomic or physiological changes alone. Rather, there may be other social and psychological factors that impinge more prominently on that performance, such as caregiving chores, altered motivation, and social discord among workers. At least potentially, this may also be true of even more abstract physiological assessments. For example, the impact of social stress on immune function is well documented (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002).

-

There may be great differences between subtle physiological measures of organs and organ systems and their effects on complex human performance. It is often uncertain whether physiological or biochemical

-

measures adequately mirror the diverse challenges and functions of many occupations.

-

Physiological and metabolic tests also may not adequately reflect cognitive, adaptive skills that come with experience and extensive training, to meet job challenges and changes.

-

As noted above, in many instances it may not be possible to distinguish the various causes of laboratory-measured decrements in function. Candidate causes of these changes include genetic forces, modifiable environmental exposures, and nascent clinical illnesses or disorders; the implications for maintaining worker health and functions are very different for each of these factors.

-

Although maximum capacity to function may be important in certain instances, most occupations do not usually require performance at full individual capacity. Thus, workplace or other exposures may cause decrements in function from full capacity without affecting work performance or function at usual levels. At the level of national economies this is particularly true since there has been a decline in the proportion of physically demanding blue-collar jobs in many industrialized countries. Conversely, there has been an increase in cognitively demanding occupations.

-

Age-related decrements in bodily physiological functions may be related to the duration as well as the number and intensity of symptoms and acute responses to physiological work stresses that almost all persons experience. That is, functional decrements may relate to temporary symptoms and conditions that alleviate over time but may be more common among older workers. For example, certain stereotypic work activities may lead to painful muscles and joints, which are not different among older or younger persons in their onset but may take longer to dissipate in older workers. Similarly, common upper respiratory infections may have longer courses among older persons, including older workers. Age-related decrements may be related to the permanent performance decrements, but only to varied persistence of temporary acute stresses.

Age-Related Changes in Various Organ Systems and Relevance to the Job Experience

Despite the cautions and conceptual issues noted above, there is substantial data on organ system-specific physiological and functional changes with age. While the various causal and contributing factors are uncertain, they are likely to include environmental exposures (including those in the workplace); genetic factors; positive and negative health behaviors; as well as medical and preventive services. The following is a brief overview of important age-related changes in organ systems that are possibly important to job exposures among older workers and the job experience:

Skeletal Muscle

With increasing age, there is a gradual loss of muscle mass, and muscles become weaker (McArdle, Vasilaki, and Jackson, 2002). Specific contractile proteins undergo alteration, and contraction itself becomes more disorganized (Larrsson et al., 2001). Age-associated changes in muscle strength occur earlier in women, who also appear to have greater loss of muscle quality (Doherty, 2001). Also, with increasing age, the time it takes to repair damaged tissue increases (Khalil and Merhi, 2000), possibly having implications for high-level physical occupational activities among older persons. Because of age-related loss of muscle strength and cardiac capacity, maximal exercise capacity and oxygen consumption clearly decline with age, even in apparently healthy persons (Fielding and Meydani, 1997). In an excellent review of age and work capacity, de Zwart, Frings-Dresen, and van Dijk (1995) noted that physical work capacity clearly declines with age, but whether physical work demands are different for older versus younger workers has not been well documented. Age-related muscle loss may have an important effect on other organs, such as respiration (Franssen, Wouters, and Schols, 2002), joint function and mobility, and vocal function.

However, while the causes of age-related muscle changes are often uncertain, it is likely that lack of continued physical training (i.e., poor exercise habits or deconditioning) plays an important role (Franssen et al., 2002). Not only may aging decrease the capacity of workers for some exertional tasks, but an increased risk of falls and balance maintenance are possible secondary consequences, suggested to occur among frail elders (Rigler, 1996). However, little research of this issue has been conducted among older workers. Weight-bearing exercise improves muscle glucose and lipid uptake, as well as strength and exercise endurance (Mittendorfer and Klein, 2001), suggesting a possible role for exercise activity in older worker health promotion programs.

Vision

Visual functions clearly undergo decrements with increasing age, with important implications for many workplace activities (West and Sommer, 2001). Age-related changes in visual function are often due to a variety of diseases and conditions that have been subject to treatment, such as hyper-tensive retinopathy, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and cataract. Some late-occurring conditions, such as macular degeneration, may be subject to only modest treatment effects. Some of these conditions are related to systemic illnesses or disorders that themselves need detection and treatment in order to help maintain optimal vision. Ocular injuries are a well-recognized occupational hazard, and preventive programs should be part of worker

health programs for all ages. However, some elements of visual function are not altered with age (Enoch et al., 1999), and a substantial proportion of these sense organ decrements, such as myopia, hyperopia, and accommodation loss, are correctable with appliances or surgical procedures, with the expectation of improved function.

Hearing

Age-related hearing loss, known as presbycusis, is very common, and can occur in 20 to 25 percent of persons 65 to 75 years of age (Seidman, Ahmad, and Bai, 2002). The causes are not well understood, and a variety of genetic and environmental factors have been suggested. There are apparently substantial differences in presbycusis among populations defined geographically or socioeconomically, suggesting the importance of nonoccupational noise and other environmental factors. Among the most important occupational causes is noise exposure, and considerable effort has been spent understanding the mechanisms and management (Prince, 2002). Other toxic exposures, including exposures to chemicals and medications, have been linked to progressive hearing loss and may have occupational implications. Some of these factors may be synergistic with occupational noise exposure.

Occupational hearing loss is an important cause of monetary compensation in the United States (Dobie, 1996). Severe hearing loss is often related to systemic illness or disorder and cochlear disease, which may have concomitant balance, communication, and other health problems that can impair worker function. While some traumatic and infectious causes of hearing loss are treatable, most occupational hearing loss is not curable, and rehabilitation must be made available (Irwin, 2000). This highlights the importance of the availability of general safety and prevention programs throughout a worker’s career. There is relatively little research into the functional and health consequences to workers of mild to moderate hearing loss.

Pulmonary Function

Physiological aging of the lung is associated with dilation of the alveoli, enlargement of airspaces, decrease in exchange surface, and loss of supporting tissue for peripheral airways. These changes result in decreased elastic recoil and increased residual volume and functional residual capacity (Janssens, Pache, and Nicod, 1999). Most dimensions of pulmonary function, measured using physiological testing methods, decline with age, due to a variety of clinical, climatic, and other factors (Babb and Rodarte, 2000). How much of this is attributable to normal aging is uncertain because of

varied exposure to environmental lung stresses—occupational and non-occupational—including cigarette smoke, air pollution, various allergens, and occupational gases, fibers, and particulates. The role of cardiac and other nonpulmonary systemic conditions is also important is assessing lung function. A large number of specific occupational lung diseases have been documented; they are beyond the scope of this report. In addition, the aging lung is susceptible to increasing risk of infection, due at least in part to structural and immune alterations, increasing the importance of immunization programs for older workers and others (Petty, 1998). Less clearly understood is the impact of ongoing pulmonary occupational exposures on existing or developing lung conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema, and the effect of well-established occupational pulmonary pathogens when exposure begins at a later age. These exposures and related medical conditions may have an effect on general human function and hence on work capacity. The net impact on the older worker will depend on the job demands and environment, as well as on individual clinical illnesses or disorders, exercise, and other hygienic habits.

Bone Health and Fracture Risk

Bone anatomy and function are not often related to occupational conditions and the older worker, but they have an important role. For example, bone may be a repository for occupational exposures, such as heavy metals and certain chemicals. Synergy of bone structure with marrow activity may be important for immune and hematological status (Compston, 2002). Older persons have decreasing bone density and increased rates of traumatic fractures; this is particularly more common among postmenopausal women than in men (Riggs, 2002), but fracture rates also vary by ethnicity and other risk factors. Lower bone density may be a risk factor for degenerative arthritis (Sowers, 2001), the leading cause of disability among older persons within industrialized countries. Poor quality maxillary and mandibular bone may lead to the need for more dental prostheses and may contribute to poorer nutritional status, leading to other health problems (Bryant and Zarb, 2002).

In job situations where the risk of falls and other unintentional injury is high, older workers will likely sustain more fractures for a given amount of trauma, due to age-related increases in bone fragility and architectural changes (Seeman, 2002). Several approaches to preventing age-related osteoporosis, other bone loss, and fractures are possible, including increasing calcium and vitamin D intake, maintaining an active exercise program, and screening and treatment for osteoporosis. The emphasis on bone health is not often prominent in worker health promotion programs, but with an increasing number of older workers, this may become more important.

Hormone replacement therapies have received attention in both women and men and may have implications for bone, muscle, skin, and other organ systems if successfully applied on a widespread basis. However, their adverse effects have not been fully evaluated.

Skin Aging

A wide variety of occupationally related skin conditions have been described, with many pathogenic mechanisms (Peate, 2002). Skin aging may be thought of as intrinsic and extrinsic, with many genetic and environmental determinants and altered cellular and biochemical activity (Jenkins, 2002). A particularly important cause of extrinsic skin aging is related to sun exposure, which in some circumstances may have occupational dimensions. This in turn leads to wrinkling, blotching, dryness, and leathering (Schober-Flores, 2001), as well as important skin cancers. Photo-aged skin, of whatever origin, is anatomically thinner and acquires increased permeability, becoming at least potentially a poorer barrier to chemical and related exposures (Elias and Ghadially, 2002). This may have implications for the rates of absorption of occupationally associated chemical and biological agents, possibly exacerbated by occupations where major or minor skin injuries occur, although little work has been done in this area. Age-related decreases in the rate of skin wound healing may also be important in certain workplaces, although there is likely to be an important role for comorbid conditions in wound healing (Thomas, 2001). As research progresses, it may be possible to add skin topics to health promotional programs in occupational settings.

Metabolism

Many changes in intermediary and xenobiotic metabolism occur with age, and these undoubtedly have great import for the older worker. For example, with increasing age, mitochondria produce less adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the body’s main metabolic source of energy, and higher levels of reactive oxygen species, which have been related to several human diseases as well as DNA instability (Wei and Lee, 2002). The aging liver is characterized by a reduction in oxidative functions, including oxidative drug metabolism (Jansen, 2002). However, the impact of age on pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics may be difficult to predict, suggesting that more studies among elders are needed (Klotz, 1998). These observations and others have implications for the general determination of whether the metabolism, toxicology, and disposition of workplace chemical exposures differ between older and younger workers as well as for understanding the impact of polypharmacy (common among older persons) on organ function

and metabolism of environmental agents. In the experimental setting, there may be age-related declines in rodent xenobiotic metabolism (Williams and Woodhouse, 1996), including the hydroxylation of benzene, possibly due to age-related changes in xenobiotic action on liver microsomes (Sukhodub and Padalko, 1999). Cigarette smoke has an age-related differential effect on pulmonary xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes (Eke, Vural, and Iscan, 1997).

Immunity

Aging is associated with general changes in immune function, although the relation of these changes to disease occurrence and survival is uncertain (Meyer, 2001), and more research is needed. An example from animal experimentation is the observation that exposure to certain immuno-suppressive xenobiotics leads to greater T. spirilas infection rates among older than younger animals (Leubke, Copeland, and Andrews, 2000). It is possible that these age-related changes impair responses to vaccines, leading to lesser protection from preventable infections (Ginaldi et al., 2001). It is possible that infection risk is altered by overtly nonimmune mechanisms—there is evidence that metal fume exposure may alter the risk of community-acquired pneumonia (Palmer et al., 2003). These observations have two immediate implications for the older worker. One is the possibly increased risk of clinical infections and the need for clinical prevention to maintain worker health. The other is the potential for increased infection risk among older workers exposed to special biological agents in the work environment. An additional potential implication is that the altered immune function among older workers may diminish the response to and protection by various vaccines (Murasko et al., 2002). Much more research is needed in this area.

Thermoregulation

Age-related changes in thermoregulatory function may be important for older workers. Older people have seasonally higher mortality rates at both high and low extremes of temperatures. Older persons, particularly those over 60 years, have a lower capacity to maintain core temperature during a cold challenge and have a reduced thermal sensitivity and a reduced thermal perception during cooling (Smolander, 2002). Thermogenesis under situations of cold stress appears to decline with age (Florez-Duquet and McDonald, 1998). Similarly, reflex sweating to heat exposure may be diminished in older persons, making them more heat sensitive, and mechanisms for this have been suggested (Holowatz et al., 2003). Whether these phenomena are important for actual job exposures to temperature extremes should be further evaluated. Worker selection factors and the modulation

of temperature extremes through environmental controls may mitigate most challenges. Response to more extreme temperatures in the workplace may also be affected by other factors, such as the presence of chronic illness or disorder, as well as level of training and physical fitness (Kenney, 1997).

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES FOR THE OLDER WORKER

There has been increasing recognition of the work-related mental health, psychosocial, and organizational issues among older workers, (Griffiths, 2000), in addition to the emphasis on physiochemical workplace hazards. This recognition may be due in part to a shift in the United States and most industrialized countries from a manufacturing to a service economy, where interpersonal issues are more apparent. As shown in the data from the Health and Retirement Survey (see Chapter 2), older workers are overrepresented in many service occupations as well as in part-time work situations. It is likely that among older persons, workers are less likely than nonworkers to have serious or severe mental illness or disorder because of the debilitating nature of these conditions. Also, not all work-related mental health problems are age-related, and some approaches to assessment, prevention, and management may be suitable for all ages. Yet, as shown in the data from the Health and Retirement Study, certain workplace situations—such as ageism, increasing physical and cognitive demands, and pressure to retire—may have disparate effects on older workers’ mental health.

Mental health problems with job implications include the consequences of work-related stress, clinical depression, and a variety of other psychological problems such as burnout, alcohol and other substance abuse, un-explained physical symptoms, and chronic fatigue as well as the secondary consequences of these conditions, such as higher injury rates (Hotopf and Wessely, 1997). In many instances older workers bring to the workplace mental health problems that may have long histories and origins outside the job setting. Common or severe mental conditions such as depression may cause stress, conflict, poor productivity (Goetzel et al., 2002), and potentially threats to individual safety and health related to the conditions or their treatments. The following discussion highlights some of the more important mental health issues for older workers and summarizes results of selected relevant studies on these issues.

Complaints of Work-Related Stress

One important issue is the proportion of older and younger workers who suffer from job-related stress. There is evidence that work-related stress impairs worker satisfaction and productivity and may cause long-term physical diseases and conditions, as well as increase the costs of absen-

teeism and low productivity (Tennant, 2001). In the Netherlands, occupational health surveys are conducted every three to five years, querying workers from various occupational and demographic groups about health complaints, health care treatment, working conditions, and work demands. With increasing age, a general increase in health and stress complaints was seen for almost all item categories, although the relationship to age was only modest. In general, women reported relatively higher complaint levels than men in almost all survey domains (Lusk, 1997). The high levels of perceived job stress by older American workers, reported in the Health and Retirement Survey, were shown in Chapter 2.

In Great Britain in 1997, mental and behavioral disorders such as stress-related symptoms were one of the most prevalent types of claim for incapacity benefit. Incapacity benefit figures reveal the number of people of working age who are unavailable for work because of ill health (Griffiths, 2000). As part of the British Labour Force Survey, a stratified random sample of 40,000 people who were working or who had worked were surveyed in 1990. When surveyed again in 1995, the prevalence rates for most illness or disorder categories had fallen, but rates of work-related stress, anxiety, depression, and musculoskeletal disorders had increased (Griffiths, 2000). Compared to younger workers, twice as many cases of psychological ill health (stress, depression, and anxiety) were reported by workers between 45 years and retirement age. However, very few cases were found in the postretirement population. This pattern was consistent between two surveys. There is some but not full support for the hypothesis that older persons who are working and also serving as caregivers have more role conflict and role overload (Edwards et al., 2002).

The relationship between job stressors and mental health also has been documented for health workers (Sutherland and Cooper, 1992). In Japan, Shigemi and colleagues (2000) conducted a prospective cohort study to investigate the effect of job stressors on mental health, using the General Health Questionnaire. It was found that workers who complained of perceived job stressors had a greater risk of mental illness or disorder than those not reporting job stressors. Specific items from the job stressors questionnaire, such as “poor relationship with superior” and “too much trouble at work” were particularly associated with higher mental health risk. While such studies do not prove that perceived job stressors cause mental illness or disorder, they point to direction for further research on the causes and potential interventions for such problems.

Depression

Several studies have examined depressive disorders and symptoms in the workplace, and an estimated 1.8 to 3.6 percent of the U.S. workforce

has major depression (Goldberg and Steury, 2001). Druss, Rosenheck, and Sledge (2000) examined data from the health and employee files of 15,153 employees of a major U.S. corporation who filed health claims in 1995. Over 70 percent of people with major depression were thought to be actively employed, and employees treated for depression incurred annual per capita health and disability costs of $5,414, significantly higher than the cost for treating hypertension. Employees with depressive illness or disorder and any other medical condition cost 1.7 times more than those with the comparable medical conditions alone.

Depressive symptoms have also been reported to be common after work-related injuries, such as in the case of claims for cumulative trauma disorders (Keogh et al., 2000). Physiochemical workplace exposures should be considered as potential causes of some depression and other mental disorders. For example, suicide rates among electric utility workers exposed to electromagnetic fields have been reported to be increased (van Wijngaarden et al., 2000), and depression rates were reported increased among women occupationally exposed to organophosphate pesticides (Bazylewicz-Walczak, Majczakowa, and Szymczak, 1999).

The relationship between work-related stress or pressure and depression has been explored in several work settings. In a review of this issue, Tennant (2001) concluded that specific, acute work-related stressful experiences contributed to depression, and that enduring structural factors in some institutions lead to various psychological problems. For example, in nurses, Feskanich et al. (2002) found that the relation between self-reported work stress and suicide was U-shaped, after adjusting for age, smoking, coffee consumption, alcohol intake, and marital status. When stress at home was also considered, there was an almost fivefold increase in risk of suicide among women in the high-stress category. However, few studies of the association between job stress and depression report the age at onset of clinical depression in study subjects. When age was studied, it was usually used for adjustment in multivariate models (e.g., Druss et al., 2000).

It is unclear how retirement affects an individual’s psychological states, including self-esteem and depression. Work gives individuals not only financial security but also can provide identity and roles. Some researchers believe that retirement creates an identity crisis, given the prominent role of work (Reitzes, Mutran, and Fernandez, 1996). Others, such as Atchley (1974), argue that individuals occupy multiple roles and can proceed to imply family, friendship, and religious roles into retirement that would prevent an overall negative consequence. Reitzes et al. (1996) followed 826 workers for two years to explore the social and psychological consequences of retirement. When comparing workers who retired to those who continued to work, depression scores declined for workers who retired, while the self-esteem scores did not change in either group. In general, depression and

depressive symptoms decline with retirement in most studies, but this may differ by gender and reason for retirement (e.g., voluntary versus forced by health or job circumstances). Cohort studies that follow individuals of both genders through retirement offer an important opportunity to explore the role of the workplace in depression among older workers.

Several methodological issues are apparent when studying depression among older workers. Occupations vary in stress generation, and there may be individual differences in response to conflict and stress. In many studies, depression and depressive symptoms are not rigorously defined, and, as noted above, age-at-onset is rarely considered. Patients with major depression often have substantial psychiatric comorbidity, such as mania or alcoholism, and the effects of drug or other psychotherapeutic regimens should be considered in assessing health or economic outcomes. Identification of depression may be problematic in any population, including workers, and may depend in part on worker mental health benefits and the attitudes and programs of employers.

Sleep Problems

A substantial number of older persons report sleep problems, including difficulty in initiating sleep, early awakening, and daytime sleepiness (Foley et al., 1999). Sleep problems among certain occupational groups such as health care workers and truck drivers have been well recognized. In one study, approximately 20 percent of truck drivers had undiagnosed sleep disorders affecting their overall functioning (Stoohs et al., 1995). Sleep disturbances caused by shift work have been shown to affect work productivity and social functioning (Regestein and Monk, 1991). Results from the study on mental health status of female hospital workers in the Paris area showed that 32 percent of the sample had symptoms of fatigue (e.g., waking up tired, working despite exhaustion) (Estryn-Behar et al., 1990); about a third of these subjects also had sleep impairment. Sleep problems were more frequent among older women and those with higher numbers of children at home.

Sleep problems have a strong relationship with both mental and physical health in general. A study by Manocchia and colleagues (2001) indicated a strong association between sleep problems and the psychological wellness of older individuals. These data, on patients with chronic illnesses or disorders from the Medical Outcomes Study, showed that 45.6 percent of the sample reported mild to severe levels of sleep problems. Sleep problems were significantly associated with a higher percentage of respondents reporting losses in work productivity and quality. Further, sleep problems were strongly associated with worse levels on the mental health scale of the

SF-36, an instrument summarizing several dimensions of health-related quality of life.

One of the consequences of sleep disturbances is dependence on prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) sleep medications. It was found that older adults and females use greater amounts of sleep medication in order to manage their sleep problems (Ohayon, Caulet, and Lemoine, 1996; Pillitteri et al., 1994; Mullan, Katona, and Bellew, 1994). Individuals who do not seek formal care for sleep problems tend to overmedicate their condition using OTC drugs.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

In recent years, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) has become increasingly recognized as a common clinical problem (Sharpe et al., 1997). The causes of CSF are unknown, but there are many variables that appear to predispose individuals to develop CFS, including various lifestyle behaviors, personality traits, and work stress. Also, CFS may make individuals more susceptible to illnesses or disorders such as viral infection and worsen existing illnesses or disorders such as sleep problems and depression. Older individuals with a declining general health may be more susceptible to developing CFS. The relationship between CFS and work factors such as workload and hours and job-related stress, as well as home stress, should be investigated further for older workers.

Alcohol and Substance Abuse

It is reported that 70 percent of current illegal drug users are employed, and approximately 7 percent of Americans employed in full-time work report heavy drinking (Roberts and Fallon, 2001). Individuals who use alcohol or other drugs in the workplace are estimated to cost business $81 billion annually in lost productivity; 86 percent of these costs are attributed to alcohol use. Ruchlin (1997) used the 1990 Health Promotion and Disease Prevention supplement to the National Health Interview Survey to determine prevalence data on alcohol use among older adults. Close to half of the sample reported having consumed alcohol during the survey year. According to Rigler (2000), one-third of older alcoholic individuals developed problem drinking in later life, while the remainder grew older sustaining the medical and psychosocial consequences of early-onset alcoholism. However, the prevalence of problem drinking and alcoholism among older workers is not known. The reported prevalence of alcohol problems among older adults in the general population ranges from 1 to 22 percent. In all age groups, the rates are lower in women than in men. In any case, the consequences of alcohol abuse are known to be more serious among the

elderly. The problem of alcohol and drug abuse at work is predicted to increase as the baby boomer cohort grows older, because this cohort had higher rates of substance use, including alcohol, than previous generations.

Of course, not all individuals with a history of alcohol abuse exhibit serious problems with drinking. A substantial number seem to be managing their lives while engaging in controlled drinking or repeating a pattern of abstinence and remission. There are few studies on effects of controlled drinking and the abstinence-remission pattern of drinking on health and function of older adults, including older workers. It is likely that many middle-aged and older adults continue to function well enough to sustain employment. Researchers point out that the currently used criteria for alcohol or substance abuse may not be sensitive enough to screen older adults who exhibit a pattern of symptoms different from those exhibited by younger drinkers. For example, many older workers may be asymptomatic cases of alcoholism. Also, a different intervention approach may be needed to help older workers who have been drinking for decades. An important research direction is to explore the relation between job stressors and alcohol abuse, for example, whether job stressors triggers alcohol abuse among abstaining individuals. Also, there is a great need to better understand later life onset of alcoholism (Liberto and Oslin, 1995).

Another underevaluated area for the future research is problems associated with medication abuse among older women. There are few studies on alcoholic women, since the prevalence of alcoholism is lower in women across all age groups. However, older women are more problematic users of prescribed psychoactive drugs than men, and a prevailing comorbidity among older women alcohol abusers is depressive disorder (Gomberg, 1995).

PSYCHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF OLDER WORKERS

Effects of Normal Aging on Psychological Functioning

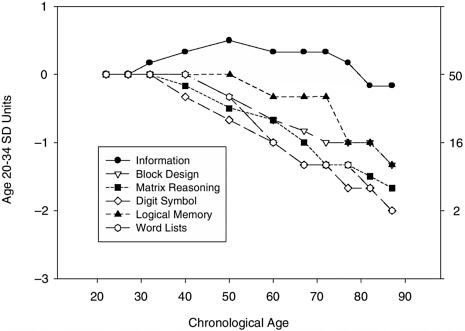

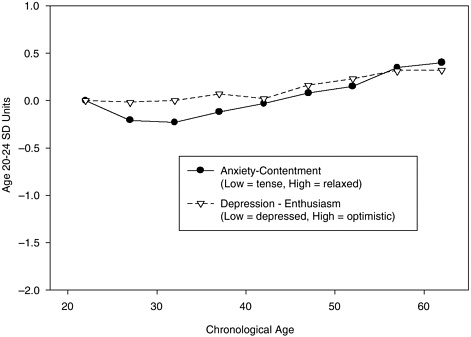

Among the major psychological characteristics of individuals are their personality or psychological adjustment and their mental (or cognitive) functioning. Relatively little change with age has been found in the level of most personality traits (see Ryff, Kwan, and Singer, 2001, and Warr, 1994, for reviews). However, increased age has been found to be associated with reports of greater happiness, less negative affect, reduced amounts of occupational stress (e.g., Mroczek and Kolarz, 1998), and lower levels of depression and anxiety (e.g., Christensen et al., 1999; Jorm, 2000). At least one study has also reported that older workers have slightly higher levels of occupational well-being than younger workers (Warr, 1992). This latter trend is illustrated in Figure 5-1. The average ratings from the question-

FIGURE 5-1 Occupational well-being.

SOURCE: See Warr, 1992.

naires are expressed in standard deviation units of young adults to provide a common scale for all variables. Use of this group as the reference distribution allows comparison levels of adults of different ages entering the workforce. Although young adults are only a subset of the total sample (and hence the estimate of the standard deviation from this subset may not be as precise as when the entire sample is used as the reference group), young adults may offer a more meaningful comparison when there are large age effects on the variable of interest because some of this variability will be due to effects of age. As is apparent in Figure 5-1, occupational well-being increases slightly across a 40-year age range, but the total effect is small, corresponding to less than .5 standard deviations of the reference distribution of young adults.

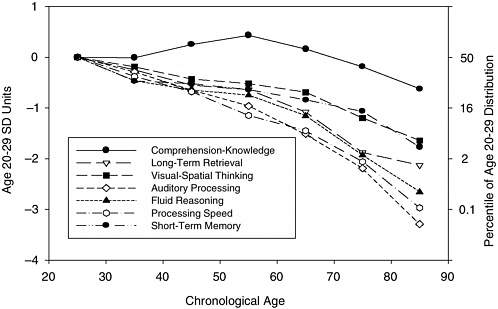

In contrast to the small and generally positive effects of age on variables related to personality or adjustment, age-related effects on many measures of cognitive functioning are large and negative. Figures 5-2 and 5-3 illustrate age trends in several cognitive variables from nationally representative samples used to establish norms from recent standardized cognitive test batteries (i.e., Wechsler, 1997a,b; Woodcock, McGrew, and Mather, 2001).

There is a slight increase up to about age 50 for measures of knowledge of word meaning and general information, but a continuous decline beginning in the 20s for variables representing memory, reasoning, and spatial abilities. The magnitude of these latter effects is about 1.5 to 2 (young adult) standard deviations between 20 and 70 years of age, which means that the average 70-year-old on these tests is performing at a level lower than that of over 90 percent of the young adults in the reference distribution. A similar pattern is evident in normative samples for other standardized tests (e.g., the WAIS, WAIS-R, WJ-R, K-BIT, and KAIT), as well as many studies examining a mixture of standardized tests and specially designed experimental tasks in convenience samples (e.g., Park et al., 2002; Salthouse, 1991, 2001; Salthouse and Maurer, 1996).

The distinction between two types of cognitive variables based on different age trends has been recognized since the 1920s. The most familiar labels for the two types of cognition are fluid and crystallized, but these terms are not very descriptive, and other labels have been proposed such as mechanics and pragmatics, or process and product. In each case the first type of cognition broadly refers to the efficiency of processing at the time of assessment, and the latter to the cumulative products of processing that occurred at earlier periods in one’s life. A considerable body of research has established that there are nearly continuous declines from early adulthood in the effectiveness of fluid, mechanics, or process cognition, as reflected in the detection and extrapolation of relationships, novel problem solving, memory of unrelated information, efficiency of transforming or manipulating unfamiliar or meaningless information, and real-time processing in continuously changing situations. In contrast, the research indicates that there are increases at least until about age 50 in crystallized, pragmatics, and product cognition, as assessed by measures of acquired knowledge. However, the true relation between age and knowledge may be underestimated in standardized test batteries, because in order to have broad applicability the assessments have focused on culturally shared information rather than idiosyncratic information specific to a particular vocation or avocation. It has therefore been suggested that continuous increases until very late in adulthood might be found if more comprehensive individualized assessments of knowledge were available (e.g., Cattell, 1972; Salthouse, 2001).

Although the group trends described above are firmly established, there is considerable variability at every age even in variables with large average age-related declines. That is, some people in their 60s and 70s perform above the average level of people in their 20s, and some people in their 20s perform below the average level of people in their 60s and 70s. The reasons for the across-person variability are still not well understood, but it is important to recognize that trends apparent at the group level may not apply at the level of specific individuals.

Two basic questions can be asked with respect to psychological aging in the context of health and safety in work. The first concerns the effects of psychological aging on safety and productivity in the workforce, and the second concerns the effects of work on the mental abilities of older workers.

Effects of Psychological Aging on the Productivity, Health, and Safety of Workers

As noted earlier, in many respects older workers appear to have higher levels of personality or emotional stability than young adults. There are consequently no reasons to expect adverse effects on health and safety related to the personality or psychological adjustment of older workers.

In contrast, negative relations might be expected between age and work performance, because cognitive abilities are important for work, and, as indicated above, increased age is associated with declines in certain aspects of cognitive functioning. However, reviews of research on aging and work performance have revealed little overall age trend in measures of job performance (e.g., Avolio, Waldman, and McDaniel, 1990; McEvoy and Cascio, 1989; Salthouse and Maurer, 1996; Waldman and Avolio, 1986; Warr, 1994). Although the reviews suggest that there is little relation between age and job performance, one should be cautious about any conclusions at the current time, because of weaknesses in many of the empirical studies. For example, most studies can be criticized for having a limited age range with few workers over the age of 50; questionable validity and sensitivity of the job performance assessments; and little control for selective survival such that only the highest performing workers may have continued on the job to advanced age (Warr, 1994). Furthermore, it is worth noting that moderate to strong negative relations between age and performance have been reported in certain cognitively demanding occupations, such as air traffic controllers (e.g., Becker and Milke, 1998) and pilots (e.g., Taylor et al., 2000), and in the magnitude of performance improvements associated with job training (Kubeck et al., 1996).

One explanation for the lack of stronger negative relations between age and work performance is a positive relation between age and job-relevant experience. Warr (1994) has speculated about a possible interaction of age and experience for performance in different types of jobs, based on hypothesized patterns of age-related and experience-related influences. He suggested that negative age relations would be expected in only a few jobs, and not in the jobs that involve knowledge-based judgment with no time pressure, relatively undemanding activities, or skilled manual work. Warr’s speculations are intriguing, but there is currently little understanding of the demands of particular jobs in terms of the relative involvement of process (or fluid or mechanics) and product (or crystallized or pragmatics) abilities,

and of the effects of experience on these abilities or on actual job performance. It is also possible that the specific effects of age and experience could vary depending on changes that occur in the workplace. For example, Hunt (1995:18) has suggested that “aging increases the value of a workforce when the workplace is static, but it may decrease the value of the same workforce if the methods and technology of the workplace are changing.”

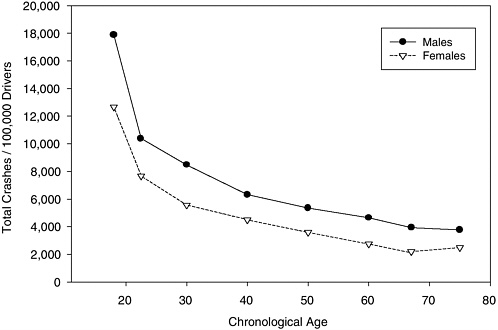

Little information is currently available about the relations between age and quality of work or about possible differences in how a given level of work is achieved by adults of different ages. Some insights on this latter issue may be available from research on driving, which is an activity with many parallels to work. Age-related declines in abilities related to driving, such as vision, reaction time, and selective and divided attention, have been well documented. However, as illustrated in Figure 5-4, there is no evidence of age-related increases in crash frequency when the data are expressed relative to the number of drivers of a given age.

FIGURE 5-4 Automobile crashes by age.

SOURCE: Table 63, Traffic Safety Facts 1999, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation.

Brouwer and Withaar (1997; also see Withaar, Brouwer, and van Zomeren, 2000) introduced a distinction among three aspects of driving that may help explain the absence of expected age-related increases in crashes (when crash rates are not adjusted for distance driven). In their classification scheme, operational aspects refer to control of the car in reaction to continuously changing traffic conditions; tactical aspects refer to voluntary choice of cruising speed, following distance, and maneuvers; and strategic aspects refer to choice of travel mode, route, and time of traveling. It is possible that older drivers rely on their stable or increasing strategic and tactical knowledge acquired through experience to minimize dependence on operational abilities that may be declining.

In fact, when crash rates are adjusted for distance driven they do start to increase with age after age 65, and it is reasonable to expect that they would increase to an even greater extent if it were also possible to take into consideration when the individual is driving and under what conditions (e.g., during the day or at night, in the middle of the day or during rush hour, etc.). The applicability of the strategic-tactical-operational distinction to occupational contexts is not yet known. However, it is certainly possible that increased age is associated with declines in operational abilities in many work situations, but that the consequences of these declines are offset by age-related increases in strategic and tactical knowledge. Furthermore, to the extent that safety is positively associated with quality or quantity of tactical and strategic knowledge, the safety of older workers may be at least as great as that of young workers because an age-related increase in job-relevant knowledge (Warr, 1994).

Certain adaptations may be required on the part of the older worker, and possibly some accommodations on the part of the employer in order to maximize the capabilities of older workers. However, there appears to be little reason to expect age-related changes in cognitive functioning to adversely affect the health, safety, or productivity of workers who are continuing in the same job and are performing familiar activities.

Experience and Expertise

Examination of the physical, psychological, and social differences between older and younger workers indicates that aging processes tend to lower some functional capacity. Increased age, however, is also associated with increased experience that tends to raise experience-related functional capacities. These two aspects of age may trade off, particularly when experience leads to skill and expertise, a point stressed in some of the earliest literature in this field (e.g., Welford, 1958).

Is there evidence that experience or expertise can mitigate general age-related declines in basic mental abilities? The reason for being concerned by

declines in general cognitive abilities is that in metanalysis studies these abilities are strong predictors (r = 0.5) of initial job performance and of job-related training performance (Schmidt and Hunter, 1998). Job experience typically correlates about r = 0.2 with job performance, with the best prediction achieved with experience levels below three years and for low complexity jobs (McDaniel, Schmidt, and Hunter, 1988). If experience compensates for age-related declines in mental ability, then older workers may not have special needs relative to younger ones. By virtue of longevity in a workplace, they might be expected to have acquired the knowledge and skills to work safely and productively.

The literature on how acquired skill may compensate for negative age-related changes is somewhat limited in scope (see reviews by Salthouse, 1990; Bosman and Charness, 1996). Research has focused on representative cognitive abilities such as spatial ability, as measured by psychometric test instruments, and memory ability, as measured by experimental tasks. Although experience and expertise usually covary, they may be only loosely connected (e.g., Charness, Krampe, and Mayr, 1996). Practice aimed at improving performance (deliberate practice) appears to be necessary for acquiring high levels of skill (Ericsson and Charness, 1994).

Experimental studies of age and skill in domains such as playing instrumental music (Krampe and Ericsson, 1996; Meinz, 2000; Meinz and Salthouse, 1998) show that experience does not fully mitigate age-related memory decline on domain-related tasks such as recalling briefly presented music notation segments. However, there is some compensation for do-main-relevant measures such as performance of music by pianists or violinists in the case of maintained practice schedules.

Studies on typing (Salthouse, 1984; Bosman, 1993, 1994) indicate that older skilled typists may compensate for normative age-related slowing in response time by using greater text preview to maintain high typing rates. The Bosman studies also indicate that for very skilled older typists there may be no need for compensation for typing the second character in a digraph.

Studies by Charness on chess playing (1981a,b) and bridge playing (1983, 1987) indicated that observed age-related declines in memory function were not predictive of game-related performance by older players. There were no age effects on problem-solving performance, just an effect of skill.

Cross-sectional studies by Salthouse and colleagues on architects and engineers showed similar rates of decline in spatial abilities for professionals whose work required spatial reasoning as for control professionals not working in environments demanding spatial reasoning (e.g., Salthouse, 1991). Archival data sources have been used to trace life-span performance in professions (e.g., Simonton, 1988, 1997). They typically show a sharp

rise in performance from the teen years to the early adult years followed by a peak in performance in the decades of the 30s followed by a slow decline. Career age seems to be the better predictor of this function than chronological age. A similar inverted backward j-shaped function can be seen for longitudinal Grandmaster performance in chess (Elo, 1965). The age of peak performance varies depending on the profession with earlier peaks observed in mathematicians and later ones in historians. The shape of the function depends on initial productivity rate, as seen in longitudinal publication patterns by psychologists. There is an earlier age of decline for higher-level performers (Horner, Rushton, and Vernon, 1986).

Studies by Morrow (Morrow, in press; Morrow et al., 1993, 1994, 2001) investigating pilot performance show that experience does not fully compensate for age-related decline when considering memory-related navigation activities such as plotting a route, read-back of air traffic control messages, answering probes about current position, and recall of the route. However, when pilots were allowed to take notes (Morrow et al., in press), minimizing the need to use internal memory, older and younger pilot accuracy was equivalent. A recent study by Guohua et al. (2003) suggests that crash rates among professional pilots do not increase as the pilots age from their 40s to their late 50s and, after age adjustment, increased flight experience was associated with markedly lower crash rates. A “healthy worker effect” may partly explain the absence of an age effect.

A concern with many of these studies (except typing, chess, and career performance) is that few had well-validated measures of expertise. Experience was used as a proxy for expertise. However, in the workplace it is also true that few firms can claim validated measures of employee expertise.

On balance, these studies suggest that acquired experience, while improving performance, may not fully compensate for age-related declines in component abilities (for instance, memory and spatial abilities), though acquired skill may play such a role for domain-related performance. As the workforce does become older, and more older adults in the higher age ranges are working, there are likely to be some issues related in the management of cognitive impairment. However, studies that attempt to address the links between basic abilities, knowledge, and professional performance specifically for older adults are relatively sparse and need to be expanded. To the extent that such laboratory behavior generalizes to the workplace, accommodative strategies would seem necessary to try to maintain and improve productivity in an aging workforce.

Effects of Work on Personality and Mental Abilities of Older Workers

The impact of work on psychological characteristics of older workers has been difficult to investigate because type of work is typically con-

founded with other factors such as intellectual ability, socioeconomic status, exposure to stressors, lifestyle, and diet. However, at least two categories of work-related influences on mental abilities can be identified. One concerns effects attributable to physical aspects of the work environment, such as exposure to toxins. An example of this type of research is a report by Schwartz et al. (2001) in which age-related declines in measures of cognitive functioning were greater for workers with a history of lead exposure than for workers without prior lead exposure. Exposure effects may be more pronounced for older workers than for younger workers because (a) the effects are often cumulative, and older workers typically have had a greater period of exposure; (b) some effects could have a long latency and may not be apparent for 10 to 20 years after the exposure when the workers are older; and (c) older adults may be more vulnerable to many types of biochemical stressors.

The second category of work-related influence on mental ability concerns the psychological nature of the work. The most relevant research within this category is a project by Schooler, Mulatu, and Oates (e.g., 1999) investigating the effects of the substantive complexity of work (based on characteristics such as closeness of supervision, variety, ambiguity, and decision making) on ideational flexibility (a form of fluid intelligence, based largely on examiner ratings). Reciprocal relations have been reported between the two constructs, such that higher ideational flexibility was associated with greater complexity of work, and more complex work was associated with less negative, or more positive, changes in ideational flexibility. The latter direction is particularly intriguing because it suggests that psychological aspects of the nature of work might influence the direction and magnitude of age-related change in cognitive ability.

Although the Schooler et al. (1999) results are encouraging, they should be viewed cautiously because some other evidence appears to be inconsistent with a positive influence of lifestyle or activity on cognitive functioning. For example, college professors, who might be assumed to have highly cognitively stimulating lives, have been found to exhibit age-related declines in cognitive abilities similar to those found in the general population (Christensen et al., 1999; Sward, 1945). Furthermore, although there are some reports of smaller age-related cognitive declines for people with more self-reported cognitive stimulation (e.g., Wilson et al., 2002), other studies have failed to find this pattern (e.g., Salthouse, Berish, and Miles, 2002), including studies focusing specifically on crossword puzzle experience, which is often recommended as a form of mental exercise (Hambrick, Salthouse, and Meinz, 1999).

Perhaps because of the difficulty in characterizing and isolating relevant dimensions of work, there has been relatively little research in which psychological characteristics have been considered as dependent variables