Test and Evaluation Challenges in Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Systems for the Department of the Air Force (2023)

Chapter: 2 Definitions and Perspectives

2

Definitions and Perspectives

An artificial intelligence (AI) system’s capability relies on the data corpus used to create the AI. This depzndency on data presents interesting challenges to traditional test and evaluation (T&E) architectures. The following chapter’s goal is to provide the reader with the fundamental definitions of these systems (Section 2.1), the role data plays in the AI life cycle (Section 2.2), and how T&E approaches have evolved in AI-enabled systems (Section 2.3). Additionally, the committee discusses the role of human-machine teaming in AI implementations and its impact on system T&E (Section 2.4). All of these distinctions warrant consideration when architecting AI-enabled systems for production deployment.

2.1 AI-ENABLED SYSTEMS

An AI-enabled system is a computer system that uses AI techniques to perform tasks that typically require advanced deductive or inductive tasks based on collected data of all types. These tasks include but are not limited to image and video analysis, predictive analytics, autonomous control and decision-making, and language and speech processing. AI-enabled systems have the potential to augment and enhance human capabilities.

There is a wide range of military applications for AI-enabled systems. A few key examples are as follows:

- Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance: AI can be used to analyze large amounts of data from sensors and other sources to identify patterns and trends and detect potential threats.

- Target identification and tracking: AI can identify and track targets, such as vehicles or individuals, using sensor data and other sources.

- Cybersecurity: AI can detect and prevent or limit cyberattacks by analyzing network traffic and identifying anomalies that may indicate an attempt to breach security.

- Enhancing situational awareness: AI-enabled systems can analyze data from various sources, such as sensors and radar, to provide military pilots with real-time situational awareness and help them make better-informed decisions.

- Autonomous weapons systems: Autonomous weapons systems may use AI to make decisions and take actions without human intervention.1

- Training and simulation: AI can create realistic training environments and simulations for military personnel, allowing them to practice and improve their skills in a controlled setting.

- Navigation and flight planning: AI-enabled systems can be used for route planning, airspace management, and obstacle avoidance tasks.

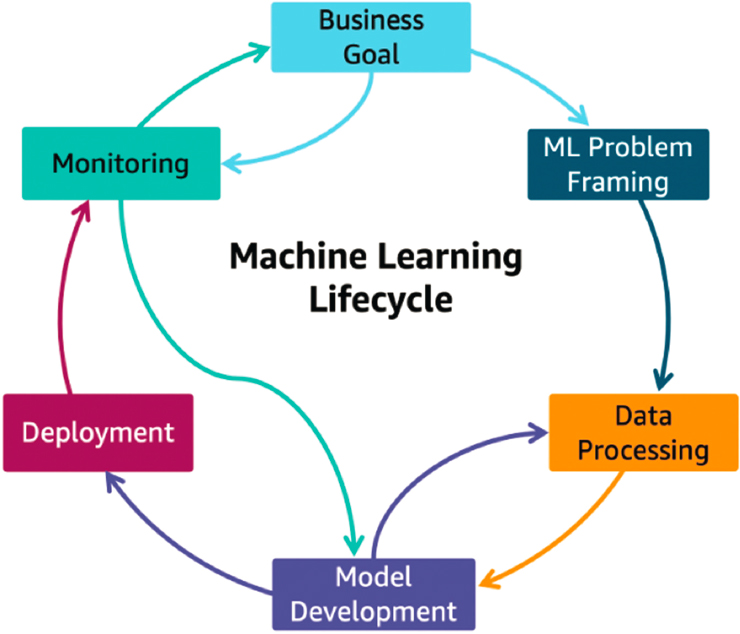

All AI-enabled systems are produced by the same cyclical generation process, known as the AI life cycle. The three basic components of the life cycle are training, inference, and re-training. Each of those three components can be further broken down into constituent steps that capture the nuance in each phase, as depicted in Figure 2-1 (although, in practice, this process is not always as linear as the figure may suggest). When combined, problem framing, data processing, and model development represent the training phase of the life cycle and yield an AI model trained to perform a given task. The deployment phase represents the operationalization of the trained model into a system where it will be asked to perform its task on new, incoming data. This phase is also referred to as the inference phase. The monitoring phase informs model development and initializes any re-training that is required. Re-training is necessary if the model’s performance deviates from what is expected once it is deployed and interacts with real-world data. The measurement and detection of that deviation, and the infrastructure and processes to manage it during training, inference, and re-training, are the subject of this report.

The training process for an AI-enabled system typically involves feeding the system large amounts of data and allowing it to learn from the patterns and relationships it discovers.

___________________

1 Department of Defense, 2023, “DoD Directive 3000.09: Autonomy in Weapon Systems,” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, https://www.esd.whs.mil/portals/54/documents/dd/issuances/dodd/300009p.pdf. In DoD, autonomous weapon systems are governed by DoD Directive 3000.09, “Autonomy in Weapon Systems.” This directive also governs the use of AI-enabled autonomous and semi-autonomous weapon systems.

2.2 ROLE OF DATA IN AI-ENABLED SYSTEMS

The amount of data that an AI requires can be enormous. For example, canonical computer vision models are trained on millions of images. Current state-of-the-art large language models have been trained on the content from millions of website pages. Training fleets for autonomous vehicle programs can produce petabytes a week that need to be processed. Data touch AI at every point in the AI life cycle, albeit in different ways, and is thus the most valuable part of the system. How data are collected, managed, curated (including labeling and assessing label quality), and maintained is crucial to the sustainability of AI systems.

Various statistical methods can be used to evaluate a model’s performance over the training period during the training of any of these systems. These statistics can be directly related to the objective function of the learning process and help to determine if the model has converged on a reasonable solution. Or they can be independent measurements that describe some other characteristic of what the model has learned so far. These measurements indicate a model’s performance relative to the data within its training corpus. For these measurements to have any

validity for operations, the training corpus must be representative of the defined operational deployment conditions. Therefore, it is a goal that the data be both sound and complete. In this context, a sound data sample is a valid sample from the input space—meaning it is a legitimate example of input data. The completeness of the data refers to how well the samples cover the input space—meaning all potential inputs have been sampled. Completeness is the distinctly more difficult characteristic to manage, yet it is incredibly important when fielding AI-enabled systems. If the completeness of a training corpus is poor, then a model will be unlikely to perform in an expected way in the field. Implicit in these requirements is that the label quality is highly emphasized.

In an AI-enabled system, operational data refers to the data collected and used by the system to perform its tasks. For example, in an autonomous vehicle system, operational data comes from various sources, such as sensors, cameras, and radar, and data from onboard systems, such as speed, location, and orientation. The AI system uses the operational data to draw conclusions about how to operate. For example, the AI system in a car may use data from the car’s sensors to detect obstacles or traffic signals and make decisions about how to safely navigate around them. The system may also use data from the car’s onboard systems to determine its location and track its progress toward its destination.

Unfortunately, real-world data are often complex, diverse, and constantly changing, making it impossible to capture and represent all possible scenarios in a single dataset. Furthermore, collecting data on all possible scenarios is often impractical or infeasible, as it may require extensive resources and time. Gathering data on rare or unusual events is extremely challenging, and the committee cannot gather data (except via simulations) on scenarios that have not yet occurred. As a result, it is generally necessary to make trade-offs when collecting and preparing data for AI training.

One common mitigation is to augment the data with synthetic or simulated data or use domain knowledge or expert insights to fill in gaps in the data. This approach may involve running full-scale simulations or modifying existing training data (e.g., different orientations). Usually, this augmentation is done in an iterative fashion wherein gaps in the learning are identified, and new data are added to fill in the gaps. It should be noted that identifying the gaps can be incredibly challenging in and of itself. Another common mitigation for many AI systems is learning continuously in real time, updating their underlying AI models based on new information. However, this is particularly vexing for testing since the system being tested is constantly changing.

These mitigations typically try to account for the lack of known or perceived completeness in the training corpus. However, even with all these adaptations, deployed models can still perform in unexpected ways when operational conditions change. The operational change can either be due to a domain shift or the advent of an unexpected scenario. This performance change is typically dealt with by retraining the model with the new observed data. The ability to re-train a deployed

model implies instrumentation in place at the deployment location to collect organized samples of the new scenario and either re-train in place or transmit the new data back to a training environment. Either way, the result of the retraining process is a newer version of the model that must be evaluated and redeployed. This process should continue for the lifetime of the model. Box 2-1 discusses some major types of training techniques.

2.3 HISTORY OF T&E IN AI-ENABLED SYSTEMS

Major applications of AI include computer vision, natural language processing, robotics, etc. Of these, computer vision applications have dominated largely due to decades of investment by DARPA and other agencies. Computer vision methods have found applications in many DoD and Intelligence Community applications

such as, automatic target recognition (ATR), image exploitation, 3D modeling and rendering, face recognition and identification, action detection and recognition, geolocation, navigation, etc., with the most recent example being Project Maven, described in Section 2.7. A recent survey2 of DARPA’s investment in computer vision and robotics summarizes the various DARPA programs since 1976 to date. The seminal paper on AlexNet, published in 2012,3 is considered a major catalyst for the re-emergence of deep learning methodologies with a tremendous impact on computer vision.

The field of AI has gone through many phases. In early years, game playing, search algorithms, rule-based systems and constraint satisfaction problems drew the attention of researchers. As an example, the famous Waltz algorithm developed in the 1970s exemplifies a constraint satisfaction problem. In the 1980s, Bayesian graphical models were developed for addressing a wide variety of decision and inference problems. In 1982, the introduction of Hopfield networks created new enthusiasm for neural networks.4 Traditional computer vision researchers were somewhat unappreciative of the three-layered neural networks that behaved like “black boxes.” Since 2012, given the performance of AlexNet on the ImageNet challenge, the tide has turned. Deep convolutional neural networks developed by LeCun and subsequently adopted in Alexnet for addressing the ImageNet challenge have become dominant in computer vision. However, some of the doubts expressed by CV researchers in the 1980s and 1990s have not gone away! AI models based on deep learning are not eminently interpretable (the black-box structure still lives on). They are as fragile as traditional CV methods, if not more so, when data are intentionally corrupted by adversarial attacks. The question of bias and fairness has emerged as a serious concern, especially in applications such as face recognition. Many concepts in AI have not transferred to data-driven AI. Only recently, efforts to integrate symbolic processing into neural computations, leading to neuro-symbolic processing,5 have emerged. The big issue is the inability of data-driven AI to incorporate rich domain knowledge. This is critical in domains such as medicine and, surely, in some DoD applications.

___________________

2 T.M. Strat, R. Chellappa, and V.M. Patel, 2020, “Vision and Robotics,” AI Magazine 41:49–65, https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v41i2.5299.

3 A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever, and G.E. Hinton, “Imagenet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks,” paper presented at Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25 (NIPS 2012), Lake Tahoe, NV.

4 J.J. Hopfield, 1982, “Neural Networks and Physical Systems with Emergent Collective Computational Abilities,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 79(8):2554–2558, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.79.8.2554.

5 G. Sir, 2022, “What Is Neuro-Symbolic Integration,” Towards Data Science, February 14, https://towardsdatascience.com/what-is-neural-symbolic-integration-d5c6267dfdb0.

While CV has existed for many decades, T&E started in earnest in the early 1980s. There are many reasons for the lag between algorithm development and T&E in computer vision: Insufficient data, lack of agreement on appropriate metrics, and the notion of end-to-end CV systems was in its infancy. One of the standard image databases available then was from the University of Southern California (USC), which had images of textures, aerial images of buildings, and some other images that were more appropriate for evaluating image compression algorithms. In the 1980s, the DARPA Image Understanding Program, in collaboration with the defense mapping agency, ventured to develop performance metrics for aerial image analysis. With the emergence of more applied programs, such as Research and Development for Image Understanding Systems (RADIUS), Uncrewed Ground Vehicle (UGV), Moving and Stationary Target Acquisition and Recognition (MSTAR), Dynamic Database (DDB), etc., from DARPA and the Face Recognition Technology (FERET) program from the Army, more data became available and standardized metrics and T&E protocols were put in place. Some examples of large-scale evaluations are the evaluation of stereo algorithms,6 face recognition algorithms,7 and SAR target recognition algorithms.8 The face recognition evaluations started in the early 1990s and morphed into a long-standing series of Face Recognition Vendor Tests9 conducted by NIST. FRVT evaluations are ongoing, involving over 300 companies and other entities, and have kept pace with changing technologies.

In computer vision, T&E efforts are often packaged as challenges that go on for some years with active participation from companies and academic groups. Some examples are given below:

PASCAL VOC Challenge

The PASCAL Visual Object Classes (VOC) challenge10 is a visual object category recognition and detection benchmark. The PASCAL VOC challenge includes three principal challenge tasks on classification, detection, and segmentation and

___________________

6 J. Kogler, H. Hemetsberger, B. Alefs, et al., “Embedded Stereo Vision System for Intelligent Autonomous Vehicles,” Pp. 64–69 in 2006 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Meguro-ku, Japan, https://doi.org/10.1109/IVS.2006.1689606.

7 DARPA, “AI Next Campaign (Archived),” https://www.darpa.mil/work-with-us/ai-next-campaign, accessed April 27, 2023.

8 SAR, 2020, “DARPA Looking for SAR Algorithms,” SAR Journal, August 3, http://syntheticapertureradar.com/darpa-looking-for-sar-algorithms.

9 National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2020, “Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT),” https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/face-recognition-vendor-test-frvt.

10 M. Everingham, L. Van Gool, C.K.I. Williams, J. Winn, and A. Zisserman, 2010, “The PASCAL Visual Object Classes (VOC) Challenge,” International Journal of Computer Vision (IJCV) 88:303–338, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-009-0275-4.

two subsidiary tasks on action classification and person layout. The challenge consisted of two components: (1) a publicly available dataset of annotated images with standardized evaluation tools and (2) an annual competition and corresponding workshop. The PASCAL VOC challenge was held annually from 2005 to 2012 and developed over the years. In 2005 when the PASCAL VOC challenge was first held, the dataset had only 4 classes and 1,578 images with 2,209 annotated objects. The number of images and annotations continued to grow, and in 2012 when the PASCAL VOC challenge was last held, the training and validation data had 11,530 images containing 27,450 ROI annotated objects and 6,929 segmentations. The PASCAL VOC challenge also witnessed a steady increase in performance over the years it was in operation. The PASCAL VOC challenge also contributed to establishing the importance of benchmarks in computer vision and provided valuable insights about organizing future challenges, which has led to a new generation of challenges, such as ImageNet.

ImageNet Challenge

The ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC)11 is arguably the most influential challenge in the computer vision community. It was run annually from 2010 to 2017 and has become the standard benchmark for large-scale object recognition. ILSVRC consists of a publicly available dataset, an annual competition, and a corresponding workshop. ILSVRC also followed the practice of PASCAL VOC, where the annotations of the test set were withheld from the public, and the results were submitted to the evaluation server. The backbone of ILSVRC is the ImageNet dataset. ILSVRC uses a subset of ImageNet images for training the algorithms and some of ImageNet’s image collection protocols for annotating additional images for testing the algorithms. ILSVRC scaled up to 1,461,406 images and 1,000 object classes in ILSVRC 2010. The ILSVRC challenge witnessed the success of deep learning and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The breakthrough came in 2012 when a deep CNN called AlexNet achieved a top-5 error of 15.3 percent, more than 10.8 percentage points lower than the runner-up. Since then, the best-performing algorithms in ILSVRC have been dominated by deep CNNs. For example, in 2015, ResNet12 achieved a 4.94 percent top-5 error rate on the ImageNet 2012 classification dataset, the first algorithm that surpasses human-level performance (5.1 percent) on the dataset.

___________________

11 O. Russakovsky, J. Deng, Hao Su, et al., 2015, “ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC),” International Journal of Computer Vision (IJCV) 115(3):211–252, https://www.image-net.org/challenges/LSVRC/index.php.

12 C. Shorten, 2019, “Introduction to ResNets,” Towards Data Science, January 24, https://towardsdatascience.com/introduction-to-resnets-c0a830a288a4.

AICity Challenge

NVIDIA Corporation, in collaboration with research groups across academia, launched an annual challenge known as AICity in 2017 to invite teams globally to compete for the development of high-performing systems for a few transportation-related tasks, including monocular speed estimation, city-scale multi-camera re-identification and tracking, anomaly detection, and natural language-based vehicle retrieval. These tasks address important and long-lasting problems in transportation which currently require many transportation analysts and significant amounts of time to solve. However, automating these tasks can provide actionable insights promptly. Traffic data for these tasks have been mainly collected from traffic cameras in the state of Iowa, curated and open-sourced accordingly. Since 2017, these datasets have motivated thousands of researchers to participate in the challenge, significantly contributed to the landscape of AI-powered transportation algorithms and extended the boundary to which computer vision can help the transportation industry.

2.4 HUMAN-MACHINE TEAMING

The modeling of human-AI (HAI) and human-machine team (HMT) interactions and how these interactions enhance or diminish human effectiveness and efficiency evolved from decades of research and development in human-systems, human-computer, and human-robot interactions. The Department of the Air Force (DAF) has over 70 years of experience integrating hardware and software of ever-increasing complexity into aircraft and spacecraft cockpits, back-end mission compartments, command and control and intelligence systems, and ground control stations.13 Aircrews’ comfort level in interacting with hardware and software systems in airplanes and spacecraft has derived primarily from extensive T&E and user feedback focused on issues such as ease of use, systems integration, reliability, failure modes, resilience, and upward compatibility. In the pre-HAI era, the combination of well-defined and well-understood developmental, operational, and follow-on T&E processes and extensive operational use led to a broad understanding of potential hardware and software failure modes, hardware and software fault or failure indications, and corrective actions. This approach generated a level of confidence that led to greater trust in aircraft systems. At the same time, lessons learned from performance limitations linked explicitly to poor cockpit design during the Vietnam War led to extensive attention on human-systems

___________________

13 The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) 711 Human Performance Wing, for example, serves as a DAF and Joint DoD Center of Excellence for human performance sustainment, readiness, and optimization. The 711th’s areas of research include biological and cognitive research, warfighter training and readiness programs, and systems integration.

teaming and aircraft cockpit and back-end ergonomics in the following decades. This culminated in developing DAF aircraft and space systems designed explicitly with human-system integration as a primary consideration.14 So far, DoD has been focused on AI that augments humans, rather than AI systems that might serve as teammates.

As one of the briefers to this committee noted however (see Appendix E), AI is fundamentally different: it is useful “to consider AI as a teammate of a different species.”15 This briefer suggested considering interactions between humans and AI-enabled machines as similar to how humans interact with their pets—a considerable difference from all previous human-machine interactions that acknowledges the differences inherent in rapidly evolving AI capabilities. AI’s incredible potential will never be unleashed without changing how humans and machines interact in a more digitized future. Optimizing the integration of humans and AI-enabled machines, which in turn depends on redesigning human-machine interfaces and recalibrating human and machine roles and responsibilities, will be one of the most important and defining features of an AI-enabled future.16 When used operationally, a human-AI system is evaluated by how well the human team using that system performs their given tasks. One fundamental measure of success is when the human-AI system performs better than either the human alone, the AI system alone, or the previous version of the human-AI system.17

As learned during Project Maven and with other AI projects at the DoD JAIC/CDAO, there are inherent limitations in adding an AI implementation as a “sidecar” to legacy systems instead of baking in AI while developing new systems. However impressive, the performance of AI-enabled legacy systems inevitably reaches a plateau. System design and development must be completely revamped to get the most out of a human-smart machine team—similar to, but much more extensive than, the approach taken to cockpit redesign in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. This applies to all AI-enabled systems, not only those embedded in aircraft or spacecraft. It demands a different approach to training humans to work with “smart”

___________________

14 The Boeing 737 Max aircraft crashes serve as a recent glaring example of poor human-system design.

15 N. Cooke, 2022, “Effective Human-Artificial Intelligence Teaming,” presentation to the committee, June 28, Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

16 This includes establishing the interdependencies between humans and machines. On the point of human-machine interdependence, see, for example, M. Johnson and J.M. Bradshaw, 2021, “How Interdependence Explains the World of Teamwork,” Pp. 122–146 in Engineering Artificially Intelligent Systems, W.F. Lawless, et al., eds., Vol. 13000 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89385-9_8.

17 The committee acknowledges the difficulty of formulating and assessing HSI-related measures of performance and measures of effectiveness, especially during the fielding of early versions of AI models that often initially perform worse than the non-AI system they are designated to replace.

machines, unlike any previous systems, to better understand how humans and machines learn and improve through repeated interactions and interventions.18 The committee underscores the importance of taking human-system integration and human-AI team effectiveness into account during the T&E of AI-enabled systems, including considering human needs and limitations as early as possible in the design and development process.19

Integrating AI elements into DAF weapon systems, decision support systems, and back-end office systems raises new challenges in the design, build, deployment, and employment stages, as well as in T&E. In addition to the human-systems integration issues noted above, T&E programs must address how to deal both with the best-case—and potentially unexpected—outcomes and unpredictable failures of AI-enabled systems. For example, AI-enabled systems are sensitive to domain shift, subject to adversarial attacks, and generally lack explainability or transparency (as discussed in Chapter 5). Additionally, a smart machine may assume more responsibilities from the human over time as human confidence in the system grows. As a result, the effective workload distribution between the end-user and the AI systems will change continuously. As systems become sufficiently advanced, the roles, responsibilities, and interdependencies between human and machine could constantly and seamlessly shift back and forth based on what humans and machines do best in each situation. In some cases, an AI-enabled machine may operate at speeds greater than the human operator is accustomed to or is comfortable with. These characteristics must all be dealt with during the AI T&E life cycle, but there are presently no clear standards to address them.

The concept of human-centered design, such as world-class user interface and user experience (UI/UX), is at the heart of every successful modern commercial software product. Too often, however, user-focused, intuitive UI/UX has not been prioritized while developing government systems. UI/UX must be one of the primary criteria considered during the design phase of all future AI-enabled systems. In a future environment characterized by the widespread fielding of AI-enabled systems, maximum performance can only be achieved by focusing on superior human-system integration, or what the U.S. Special Competitive Studies

___________________

18 See, for example, this story on the new roles of AI “prompt engineers”: D. Harwell, 2023, “Tech’s Hottest New Job: AI Whisperer. No Coding Required,” The Washington Post, February 25, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/02/25/prompt-engineers-techs-next-big-job.

19 See, for example, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022, Human-AI Teaming: State-of-the-Art and Research Needs, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. This report was written as a result of the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) 711th Human Performance Wing’s request to the National Academies to examine the requirements for appropriate use of AI in future operations.

Project (SCSP) refers to as human-machine cognitive collaboration (HMC).20 In an AI-enabled digital future, users of AI-enabled systems analysts should be able to train with smart machines so that those systems adapt to an individual’s preferences, the pace of their cognitive development, and even their past behaviors. As technology advances rapidly, highly-tailored human-machine interaction and interdependence are achievable.21 Human-machine testing and training processes will be vital to better understanding human-machine team composition, optimal assignment of human and machine roles and responsibilities, and effective and efficient workflow integration.22

In addition, these efforts should consider both technology readiness levels (TRLs) and human readiness levels (HRLs) and incorporate continuous assessments of human-machine team performance.23 The consideration of HRL, while always important, becomes critical for AI-enabled systems that depend on continuous human interaction, as opposed to traditional pre-AI systems that primarily report results for human consideration. Substantial and sustained human intervention has compensated for poor HRLs in earlier and current fielded military systems. In future AI-enabled systems, human-machine integration must accord equal consideration to HRL and TRL. Otherwise, the DAF can expect sub-optimal

___________________

20 This report makes the distinction between human-machine cognitive collaboration (HMC) and human-machine combat teaming (HMT). HMC focuses primarily on cognitive tasks, while HMT “will be essential for more effective execution of complex tasks, especially higher-risk missions at lower human costs” (p. 25). See Special Competitive Studies Project, 2022, Defense Interim Panel Report: The Future of Conflict and the New Requirements of Defense, Arlington, VA, https://www.scsp.ai/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Defense-Panel-IPR-Final.pdf.

21 Johnson and Vera examine the importance of human-machine “teaming intelligence.” They argue that “no AI is an island” (p. 18), meaning that there is no such thing as a completely autonomous system. Humans are always involved at some level, from design and development through oversight of fielded systems. M. Johnson and A. Vera, 2019, “No AI Is an Island: The Case for Teaming Intelligence,” AI Magazine 40(1):16–28, https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v40i1.2842.

22 Guillory and Carrola refer to the concept of “Cognitive Mission Support,” which they define as systems designed to help humans deal more effectively with the inevitability of information and cognitive overload (p. 3). S.A. Guillory and J.T. Carrola, 2022, “What Online-Offline (O-O) Convergence Means for the Future of Conflict,” Information Professionals Association, August 3, https://information-professionals.org/what-online-offline-convergence-means-for-the-future-of-conflict.

23 Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) are a method for estimating the maturity of technologies during the acquisition phase of a program. TRLs are measured from TRL 1 (basic principles observed) to TRL 9 (actual system proven in its operational environment). The Human Factors and Ergonomics Society notes that “many system development programs have been deficient in applying established and scientifically-based human systems integration (HSI) processes, tools, guidance, and standards, resulting in suboptimal systems that degrade mission performance” (p. 1). This draft paper includes a useful table assessing program risk due to HRL-Technology Readiness Level (TRL) misalignment (p. 6). See Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 2021, Human Readiness Level Scale in the Human Development Process, ANSI/HFES 400-2021, draft version, Washington, DC, https://www.hfes.org/Portals/0/Documents/DRAFT%20HFES%20ANSI%20HRL%20Standard%201_2_2021.pdf.

results from both humans and machines. During testing, training, and fielding, overall human-system team performance can be optimized through continuous human feedback to the system as it returns its results.

Human-AI interactions are more intriguing and interesting as all such interactions are based on trustworthiness. A recent review of the literature has identified the following six grand challenges that need to be addressed before efficient, resilient, and trustworthy HAI systems can be deployed. The six challenges are “developing AI that (1) is human well-being oriented, (2) is responsible, (3) respects privacy, (4) incorporates human-centered design and evaluation frameworks, (5) is governance and oversight enabled, and (6) respects human cognitive processes at the human-AI interaction frontier.”24 The committee recommends that the DAF adopt and adapt similar principles (although this list does not reflect a prioritization scheme) when designing, developing, testing, fielding, and sustaining AI-enabled systems (in Chapter 3, the committee discusses in more detail the core concepts of trust, justified confidence, AI assurance, and trustworthiness).

The pace at which humans and AI make decisions is a challenge for HAI systems. Whether humans will trust smart machines is a major concern. It is especially acute when considering AI’s role in supporting combat operations. However, since trust is typically perceived as a binary yes-or-no concept, rather than considering whether end-users will “trust” their AI-enabled machines, we should consider instead how users gain justified confidence in smart systems over time. The process of building confidence in any AI-enabled system is continuous and cumulative. It never ends. A user’s confidence in a smart system will depend on context: the nature and complexity of the task, the system’s previous performance record, the user’s familiarity with the system, and so on. In general, continued successful performance in lower-risk, lower-consequence tasks will give users more confidence in using AI when facing higher-risk, higher-consequence tasks. Until users gain more experience teaming with smart machines, they will face the dilemma of placing too much or too little confidence in their AI-enabled systems. The committee develops these concepts further in Chapter 3.

Finding 2-1: The DAF has not yet developed a standard and repeatable process for formulating and assessing HSI-specific measures of performance and measures of effectiveness.

Conclusion 2-1: The future success of human-AI systems depends on optimizing human-system interfaces. Measures of performance and effectiveness, to include

___________________

24 O.O. Garibay, B. Winslow, S. Andolina, et al., 2023, “Six Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Grand Challenges,” International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 39(3):391–437, https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2153320.

assessments of user trust and justified confidence, must be formulated during system design and development, and assessed throughout test and evaluation and after system fielding.

Recommendation 2-1: Department of the Air Force (DAF) leadership should prioritize human-system integration (HSI) or HSI across the DAF, with an emphasis on formulating and assessing HSI-specific measures of performance and measures of effectiveness across the design, development, testing, deployment, and sustainment life cycle.