Can we measure water underground from space?

Based on Science

Yes. Using satellites to detect changes in Earth’s gravitational pull can tell us about the movement of water on the planet, including water that is underground. Changes in those measurements over time let us know where groundwater is increasing or decreasing.

Last update May 24, 2022

Groundwater is an unseen but critical resource to our daily lives.

Fresh water comprises just 2.5% of the water on Earth. Of that 2.5%, about a third is available as groundwater—that is, water reserves found underground. A little over 1% of fresh water is on the surface of Earth, in rivers, lakes, streams, and reservoirs. The rest is trapped in ice.

Groundwater is a source of drinking water for billions of people. About half the people in the world get their drinking water from aquifers. Groundwater is also a major source of water used for crop irrigation. Much of the water used to run sanitation systems and operations in industrial processes also comes from underground sources.

Measuring changes in groundwater is important because small changes in the amount can have large negative consequences

Even though there is a lot of water below the ground compared to the water on the land surface, only a small amount can be pumped without causing negative side effects. Using too much water can cause the land surface to sink, a process called subsidence. Depleting groundwater can also dry up rivers and ecosystems that depend on water from those underground reserves (through baseflow). In coastal areas, excessive pumping of groundwater can reduce the flow of fresh water to the ocean, allowing saltwater to move toward the land and infiltrate the aquifer. If aquifers are contaminated with saltwater or depleted from over-pumping, people who depend on groundwater for personal consumption are at risk of having poor quality water and possibly no water at all.

Until recently, measuring changes in the amount of water underground was difficult. Groundwater is hidden under Earth’s surface, in some cases in deep aquifers or in aquifers that are in remote, hard-to-access areas. Equipment and techniques to measure this resource were expensive and time-consuming in high-income countries and simply not an option in low-income countries.

Taking measurements of Earth’s gravity from space has helped solve this problem.

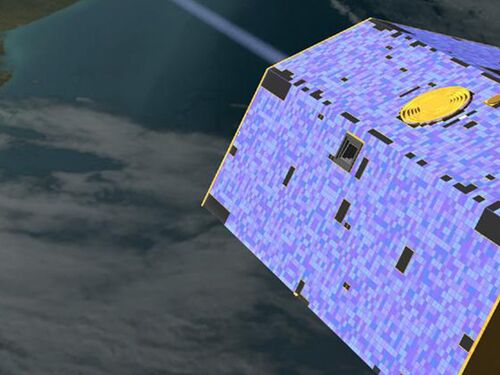

In 2002, the U.S. and German space agencies launched a pair of satellites called the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE). These two satellites, orbiting at the same altitude but 137 miles (220km) apart, used microwave pulses to measure, within a hair’s width, any change in the distance between them. For example, as the first satellite moved over a mountain, the landmass would strengthen Earth’s gravitational pull on the satellite, causing it to speed up. The microwave pulses would track the change in the distance between the two satellites as the first one sped ahead and then slowed once it moved beyond the gravitational pull from the mountain below. Then, as the second satellite passed over the same mountain, the change in distance would be detected again. Global positioning system (GPS) instruments identified the exact location of the satellites. With each orbit of the planet, the combined microwave and GPS data were used to make maps that showed how the gravity of the world changed, if it changed at all.

Earth’s gravitational pull does not change much because landmasses such as mountains do not move. But water does move, and the satellites’ measurement tools are sensitive to capture the movement. Therefore, by measuring the small changes in gravitational pull, scientists are able to tell where underground water resources are increasing or decreasing.

Scientists have used these measurements, along with hydrological models, to identify where groundwater is being depleted. For example, studies using GRACE data from 2003 to 2013 found that 13 of Earth’s 37 largest aquifers were being rapidly drained by humans, with little or no natural recharge.

The measurements taken by the GRACE satellites revealed many new insights into Earth’s water cycle. The first set of satellites ceased operating in 2017. A new set of satellites was launched in 2018 and continues to collect observations on Earth’s groundwater, the amount of water in lakes and rivers, changes in ice sheets and glaciers, and changes in sea level and ocean currents. Along with understanding changes of groundwater in aquifers, these observations help us track the melting of ice sheets and monitor drought.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine – Earth Sciences | Topic

Groundwater: Tracking Groundwater Changes Around the World – NASA

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

More like this

Events

Right Now & Next Up

Stay in the loop with can’t-miss sessions, live events, and activities happening over the next two days.

TRB Annual Meeting | January 11 - 15, 2026

January 11 - 15, 2026 | The TRB Annual Meeting brings together thousands of transportation professionals worldwide for sessions across all modes and sectors.