1

Introduction

The Clean Air Act (CAA) requires the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to set National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for six ambient air pollutants that are reasonably expected to present a danger to public health or welfare.1 These pollutants, known as the “criteria pollutants,” are carbon monoxide, lead, oxides of nitrogen, particulate matter, ozone and related photochemical oxidants, and sulfur oxides. The term “criteria pollutant” derives from the CAA requirement that EPA establish the scientific criteria for their regulation by describing the characteristics and evidence of health and welfare effects of those pollutants. Health effects are those adverse impacts on human health; welfare effects include impacts on soils, water, agriculture, forests, wildlife, human-made materials, atmospheric visibility, and climate. The CAA also requires periodic EPA review of the NAAQS for each criteria pollutant. Based on that review, the EPA administrator is to decide whether the existing NAAQS are adequate to protect public health and welfare and should be retained, or whether scientific evidence indicates revisions are necessary.

To carry out a NAAQS review, EPA’s Office of Research and Development (ORD) conducts Integrated Science Assessments (ISAs) that include evaluation of the relationship between the criteria pollutants and health and welfare effects. The general ISA approach, including the framework used to assess causality, is summarized in EPA’s Preamble to the Integrated Science Assessments (EPA, 2015a) and is applied to the ISAs for all of the criteria pollutants. ISAs published since 2015 have augmented the framework in some respects, but these changes have not been collected into a single comprehensive document. ISAs serve as the scientific foundation for NAAQS reviews and subsequent policy decisions.

The causal determination framework, as specified in the Preamble, provides an outline for evaluating weight of evidence and drawing scientific conclusions and causal judgments on health and welfare effects. The ISA combines information and data gleaned from the relevant scientific literature and expert scientific judgment to assess the causal relationship between the criteria pollutant

___________________

1 See 42 U.S.C. § 7408–7409 (https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2019-title42/html/USCODE-2019-title42-chap85-subchapI-partA-sec7408.htm and https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2019-title42/html/USCODE-2019-title42-chap85-subchapI-partA-sec7409.htm; both accessed January 10, 2022).

in question and various health and welfare impacts. A significant portion of the body of evidence on health and welfare effects of air pollution involves observational studies, so understanding design and analysis approaches for such studies becomes an important part of this assessment. Drawing causal inferences requires expanding understanding beyond evidence of associations, whether through individual study design or through combining multiple lines of evidence that bring in mechanistic understanding and address the strengths and limitations of individual studies.

There is a long historical basis for addressing the issue of causality. There are many different types of models in use in studies for making causal determinations, including both aspects of providing support for assessing a causal association (e.g., developing data that are then used in assessing associations) as well as for assessing causal associations directly. Numerous causal inference design and analysis tools have been developed and used over the past four decades, and with them, new understanding of the assumptions required to draw causal inferences. However, critics raise questions about these techniques or the appropriate level of reliance on these approaches by EPA for causal assessment in NAAQS reviews (see Chapter 6 for a discussion on critiques of the ISA). Given the importance of ISA results to establishing the primary and secondary NAAQS, the EPA ORD requested the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) to consider existing frameworks for integrating, documenting, and evaluating scientific evidence for assessing causality of health and welfare effects, describe how EPA’s methods for classifying the weight of evidence for causation (i.e., what EPA terms “causal determinations”) might be refined, and make recommendations related to the development and use of a future causal determination framework.

STATEMENT OF TASK

Under the sponsorship of EPA, the National Academies convened an ad hoc committee of experts to examine the current EPA framework used for the development of ISAs and to consider elements of other frameworks for assessing causality that might inform improvement of the Preamble’s causal determination framework. The Statement of Task provided to the committee is provided in Box 1.1. The committee is asked to examine the appropriateness of EPA’s criteria for and reporting of causal relationships, to assess new approaches for integrating and evaluating evidence (both within and among scientific disciplines) to inform causal determinations, and to consider issues regarding potential confounders.

The charge to the committee and this report are focused on the assessment of causality as determined by the Preamble’s framework. EPA uses a definition of “cause” originally articulated in the 1964 Surgeon General’s report (HEW, 1964) and highly related to the idea of potential outcomes: a “significant, effectual relationship between an agent and an associated disorder or disease in the host” (EPA, 2015a, p. 18). The committee was not asked to conduct a review of the ISA process, but rather to consider how the science that informs the causal determination framework might be advanced to increase confidence in ISA conclusions. The committee does not review conclusions of past ISAs, the NAAQS themselves, nor processes for deciding on NAAQS. The committee does examine specific processes that have been applied in past ISAs to determine their appropriateness for inclusion in a future causal determination framework.

COMMITTEE COMPOSITION

Members of the ad hoc committee that conducted the study and prepared this report were nominated by their peers and selected by the National Academies based on their professional qualifications and after careful consideration of any undue bias or conflict of interest. The committee includes researchers and practitioners with expertise in atmospheric sciences, statistics and bio-

statistics, epidemiology, biogeochemistry, toxicology, exposure science, dosimetry, public health, terrestrial and aquatic ecology, and regulatory decision making for air pollution control. Individuals who have served on EPA’s Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC), the advisory group that provides advice to the EPA administrator on the technical bases for EPA’s NAAQS since the development of the Preamble in 2015, were not considered for committee membership to avoid the appearance of bias or conflict, however, individuals that served on individual NAAQS review panels have been included as experts on the conduct of recent ISAs. Information about the National Academies’ review process may be found on the National Academies’ website.2

INTERPRETATION OF TASK AND STUDY BOUNDARIES

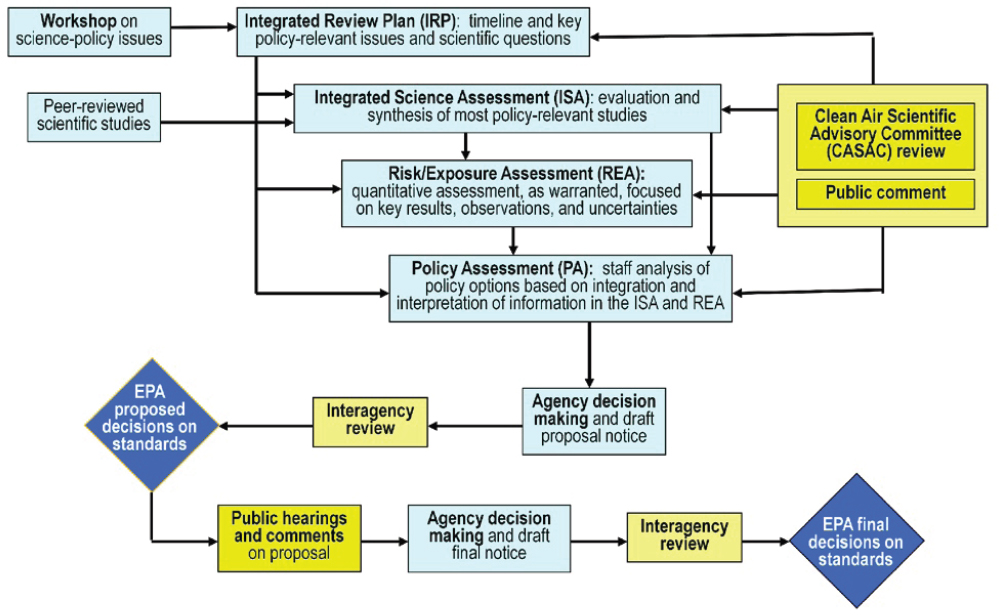

The committee interpreted its task based on early discussions with and presentations by EPA staff. The committee adopted definitions of “health” and “welfare” from those discussions, from the CAA, and from decisions of the courts (see Box 1.2). As stated above, the task is focused on the ISA and not on other parts of the NAAQS review process, including deciding whether NAAQS need to be revised (see Figure 1.1 for a diagram illustrating the different parts of the NAAQS review).

___________________

2 See https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/information.aspx?key=Committee_Appointment (accessed January 10, 2022).

SOURCE: EPA, 2015a.

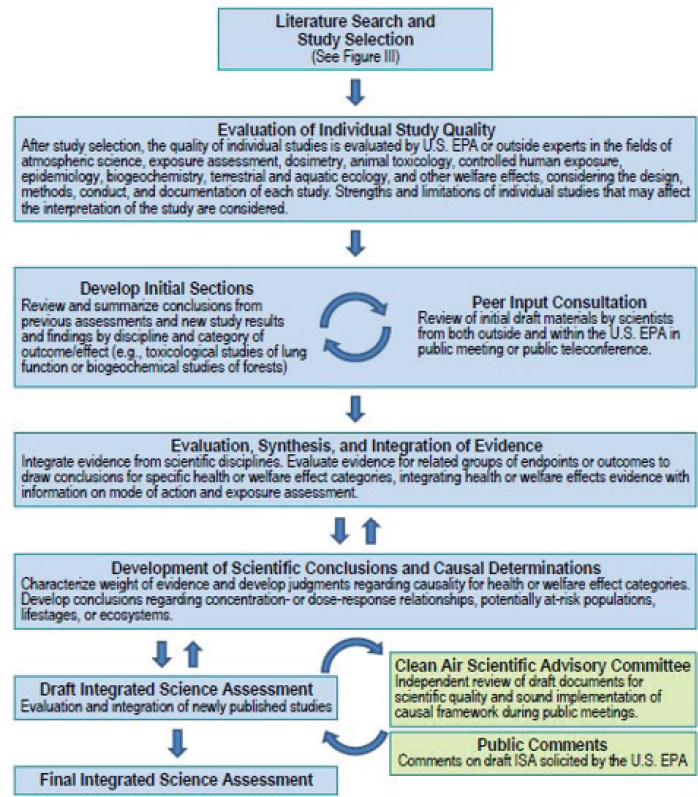

EPA staff described the Preamble (EPA, 2015a) as the framework for conducting ISAs, but also described that additional processes have been developed since the 2015 publication of the Preamble and published in subsequent ISAs. Those new processes have been used and refined in later ISAs, and their descriptions have become de facto addendums to the Preamble. To bound the task, the committee considers the Preamble to be the causality framework and cites those later processes separately, but the committee did not attempt to identify formally all those processes. A flowchart showing the EPA process for conducing its ISAs as described in the Preamble is shown in Figure 1.2. The committee focused its efforts only on processes that occur within Figure 1.2.

The Preamble includes a section titled “Framework for Causal Determinations” that describes the five-level hierarchy that classifies the weight of evidence for causation for both health and welfare effects. That section provides a general description for how to apply the weight of evidence approach, but provides no specificity on what the weight of evidence process is. Similarly, the framework does not specify each study to be used, but does inform how studies are chosen and used. Because integrating and evaluating scientific evidence involves weighing individual study importance, and therefore evaluation of individual study quality, the committee considers this an important aspect of causal determinations.

The committee does not provide a review of EPA or its processes, but rather examines processes for assessing causality that EPA might choose to incorporate into future causal determina-

SOURCE: EPA, 2015a.

tions. Similarly, the Statement of Task asks the committee to “consider frameworks for integrating, documenting, and evaluating scientific evidence to assess causality of health and welfare effects.” The committee considered numerous frameworks used by national and international organizations and ultimately focused on nine of those frameworks for determining causality or causal relationships that were most similar in purpose to the Preamble’s causal determination framework. The committee did not conduct comprehensive reviews of those frameworks, but rather considered processes within those other frameworks that might be further investigated by EPA as potential approaches that might be incorporated in a future causal determination framework.

The report includes recommendations related to the development and use of causal determination frameworks for causal determinations and areas appropriate for investigation to improve future causal determination frameworks. The notion of a framework is key—the committee viewed a framework as a blueprint that guides how a process or series of processes are conducted. The essential components of the Preamble’s causal determination framework are (1) the types of evidence to be used; (2) how studies are evaluated for quality and relevance; and (3) how causal determinations are inferred from the body of included studies. The causal determination framework is designed to support the ISA evidence review, the resulting causal determinations, and ultimately the NAAQS decisions. The results from applying the framework are based on what evidence is available. While the body of available evidence differs from one ISA review to another, the same framework may still be used.

CAUSAL DETERMINATIONS

The early focus for determining causality was on identifying the causative etiological agent for a specific disease diagnosed by a common set of chemical signs and symptoms in an individual and, then, in populations. Later, this would include a confirming diagnosis based on a pathologic examination or isolation and identification of the etiological agent. Concerns related to causality have broadened from a single etiological factor related to an individual disease (such as the smallpox virus), and a specific health endpoint (pox) to a more complete world. That world is concerned with a broad range of etiological factors and with a range of disease endpoints such as cancer (in reality more than 100 different diagnostic entities), cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, immune disorders, and other adverse health outcomes caused by or influenced by a growing array of factors.

The Statement of Task requires the committee to consider the appropriateness of EPA’s causal determinations, and specifically any refinement of the five categories described in the Preamble. In evaluating and integrating evidence on health effects of criteria pollutants, EPA considers various aspects of causality, principally those proposed by Bradford Hill (Hill, 1965). Hill proposed a set of nine aspects to establish which occupational hazards cause sickness and injury and to help identify evidence of causality from analyses of observational data. Those aspects have since been used as a basis for assessing causality in several fields, including air pollution epidemiology (Fedak et al., 2015), and are referenced in the current causal determination framework (Table I of the Preamble). Information about the evolution of the use of the Bradford Hill aspects of causality can be found in the Chapter 2 discussion of the history of the Preamble. The aspects include strength of association, consistency, specificity, temporality, biological gradient, plausibility, coherence, experiment, and analogy. The original term “aspects” is used in this report to avoid confusion with “criteria” as used in the CAA.

None of these aspects is operationally defined—it is not possible to simply examine a study or multiple studies and to automatically evaluate their contributions to any specific aspect. In every case, judgment is needed based on experience with similar studies, knowledge of the field of study, and detailed examination of methodologies used and results obtained, often guided by pitfalls found post hoc in conception, construction, implementation, and interpretation of prior studies. Such judg-

ments are applied by experts with the object of obtaining a weight of evidence as to the relevance and accuracy of each study in relation to each aspect.

ISAs apply such weight of evidence evaluations to classify causality of health and welfare effects of a criteria pollutant into one of five hierarchical causal categories defined by EPA and described in Table 1.1 (note that the committee’s discussion of the categories appears in later chapters). The descriptions of the categories were informed by previous reports including the U.S. Surgeon General’s report “The Health Consequences of Smoking” (CDC, 2004),1 the EPA Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment (EPA, 2005), and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Improving the Presumptive Disability Decision-Making Process for Veterans (IOM, 2008). The Preamble notes that a four-category weight of evidence hierarchy was used in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and IOM frameworks, but a five-category hierarchy was chosen “to be consistent with the five-level hierarchy used in the U.S. EPA Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment and to provide a more nuanced set of categories” (EPA, 2015a).

The Preamble’s causal determination framework does not call for formulaic approaches to causal determination in general and likewise does not quantitatively score study quality. Rather, the ISAs are intended to describe the strengths and limitations of studies to characterize the evidence and support judgments on the extent of error, bias, and strength of inference from results. Assessments of study quality are based on the judgments of ISA authors and are evaluated by CASAC as part of its review of a draft ISA.

COMMITTEE INFORMATION GATHERING

The committee relied on numerous sources of information in the formation of this report. Three public meetings were held during which the committee heard from a variety of experts with a range of perspectives. Appendix B includes agendas of the open session meetings, which were all held remotely due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The committee’s first open session meeting included presentations by and discussions with EPA representatives to be introduced to the Statement of Task, the Preamble’s causal determination framework, the purpose of the study, and the study boundaries. The second open session meeting included input from several industry representatives regarding critiques of the causal determination framework. Formal presentations were made by Dr. Tony Cox (Cox Associates and former chair of CASAC under Administrators Pruitt and Wheeler) and Dr. Julie Goodman (Gradient), and there were additional remarks by and a panel discussion with Barbara Beck (Gradient), Howard Feldman and Ted Steichen (American Petroleum Institute), and Giffe Johnson (National Council for Air and Stream Improvement). A second session of that meeting focused on evidence synthesis when assessing causality and included a panel discussion with Sherri Rose (Stanford University), David Savitz (Brown University), and Jon Samet (Colorado School of Public Health). A third open session meeting continued discussion of scientific critiques of the Preamble’s causal determination framework from the public health and welfare perspectives with a panel discussion including John Bachmann (Vision Air Consulting), Ananya Roy (Environmental Defense Fund), Gretchen Goldman (Union of Concerned Scientists), Georgia Murray (Appalachian Mountain Club), and Bret Schichtel (National Park Service).

In addition to the formal open session meetings, the committee organized webinars with individuals. In one webinar, the committee received input from Wim de Vries of Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands to learn about and discuss the history of relevant air pollutant protocols in the European Union in relation to the derivation of critical levels and loads for nitrogen and acidity and the science behind them. In a second webinar, the committee heard from Dan Greenbaum (president of the Health Effects Institute). Dr. Greenbaum compared frameworks from other countries with the framework used by EPA for developing causal determination frameworks as part of the ISAs.

TABLE 1.1 Weight of Evidence for Causal Determination

| Health Effects | Ecological and Other Welfare Effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Causal relationship | Evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship with relevant pollutant exposures (e.g., doses or exposures generally within one to two orders of magnitude of recent concentrations). That is, the pollutant has been shown to result in health effects in studies in which chance, confounding, and other biases could be ruled out with reasonable confidence. For example: (1) controlled human exposure studies that demonstrate consistent effects, or (2) observational studies that cannot be explained by plausible alternatives or that are supported by other lines of evidence (e.g., animal studies or mode of action information). Generally, the determination is based on multiple high-quality studies conducted by multiple research groups. | Evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship with relevant pollutant exposures. That is, the pollutant has been shown to result in effects in studies in which chance, confounding, and other biases could be ruled out with reasonable confidence. Controlled exposure studies (laboratory or small- to medium-scale field studies) provide the strongest evidence for causality, but the scope of inference may be limited. Generally, the determination is based on multiple studies conducted by multiple research groups, and evidence that is considered sufficient to infer a causal relationship is usually obtained from the joint consideration of many lines of evidence that reinforce each other. |

| Likely to be a causal relationship | Evidence is sufficient to conclude that a causal relationship is likely to exist with relevant pollutant exposures. That is, the pollutant has been shown to result in health effects in studies where results are not explained by chance, confounding, and other biases, but uncertainties remain in the evidence overall. For example: (1) observational studies show an association, but copollutant exposures are difficult to address and/or other lines of evidence (controlled human exposure, animal, or mode of action information) are limited or inconsistent, or (2) animal toxicological evidence from multiple studies from different laboratories demonstrate effects, but limited or no human data are available. Generally, the determination is based on multiple high-quality studies. | Evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a likely causal association with relevant pollutant exposures. That is, an association has been observed between the pollutant and the outcome in studies in which chance, confounding, and other biases are minimized but uncertainties remain. For example, field studies show a relationship, but suspected interacting factors cannot be controlled, and other lines of evidence are limited or inconsistent. Generally, the determination is based on multiple studies by multiple research groups. |

| Suggestive of, but not sufficient to infer, a causal relationship | Evidence is suggestive of a causal relationship with relevant pollutant exposures but is limited, and chance, confounding, and other biases cannot be ruled out. For example: (1) when the body of evidence is relatively small, at least one high-quality epidemiologic study shows an association with a given health outcome and/or at least one high-quality toxicological study shows effects relevant to humans in animal species, or (2) when the body of evidence is relatively large, evidence from studies of varying quality is generally supportive but not entirely consistent, and there may be coherence across lines of evidence (e.g., animal studies or mode of action information) to support the determination. | Evidence is suggestive of a causal relationship with relevant pollutant exposures, but chance, confounding, and other biases cannot be ruled out. For example, at least one high-quality study shows an effect, but the results of other studies are inconsistent. |

| Health Effects | Ecological and Other Welfare Effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate to infer a causal relationship | Evidence is inadequate to determine that a causal relationship exists with relevant pollutant exposures. The available studies are of insufficient quantity, quality, consistency, or statistical power to permit a conclusion regarding the presence or absence of an effect. | Evidence is inadequate to determine that a causal relationship exists with relevant pollutant exposures. The available studies are of insufficient quality, consistency, or statistical power to permit a conclusion regarding the presence or absence of an effect. |

| Not likely to be a causal relationship | Evidence indicates there is no causal relationship with relevant pollutant exposures. Several adequate studies, covering the full range of levels of exposu that human beings are known to encounter and considering at-risk populations and lifestages, are mutually consistent in not showing an effect at any level of exposure | Evidence indicates there is no causal relationship with relevant pollutant exposures. Several adequate studies re examining relationships with relevant exposures are consistent in failing to show an effect at any level of exposure. . |

SOURCE: EPA, 2015a.

Committee members augmented the information gathered through the above interactions with one-on-one discussions with national and international experts on a variety of topics; they consulted past ISAs and the scientific literature; and they relied on their own collective and extensive expertise.

REPORT ORGANIZATION

This report is organized into 10 chapters. Chapter 2 provides some historical and legal perspectives regarding the NAAQS and development of the EPA causal determination framework and publication of the Preamble. Chapter 3 defines causality from different perspectives relevant to the ISA. Chapter 4 provides perspectives regarding the types of evidence and the influence of the individual study on the body of evidence used in a weight of evidence approach. A discussion how evidence is integrated and synthesized for both health and welfare effects is provided in Chapter 5. Chapter 6 includes examples of critiques of the ISA process and EPA’s causal determination framework. In Chapter 7, the study committee summarizes various other frameworks for causal determination, or which contain aspects of such determinations, and contrasts them with the causal determination framework found in the Preamble. An exploration of emerging methods for observational studies that could contribute to causal determinations is provided in Chapter 8. The committee responds to the question raised in its task regarding the appropriateness of a single framework for assessing causality for both health and welfare effects and provides a synthesis of its conclusions and recommendations regarding improvements to a future causal determination framework in Chapters 9 and 10, respectively. Various kinds of models used for assessing causality are described throughout the report.

One requirement of the Statement of Task is to address “whether a single framework and practices related to it for assessing causality may be applied to both health and welfare effects.” Readers may feel that much of the discussion of the methods used for causal inference and causal determinations in this report is slanted toward health versus welfare. This reflects the literature in the area, not bias on the part of the committee. Any perceived bias should not be construed to suggest the importance of one over the other.

This page intentionally left blank.