Advancing the Framework for Assessing Causality of Health and Welfare Effects to Inform National Ambient Air Quality Standard Reviews (2022)

Chapter: 7 Illustrative Frameworks for Causal Determinations

7

Illustrative Frameworks for Causal Determinations

Previous chapters describe the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) framework for assessing causality in its Integrated Science Assessments (ISAs), as described in the Preamble (EPA, 2015a). Other governmental or nongovernmental organizations have developed their own approaches for determining causality to inform environmental health decision making or in guiding public health recommendations. Those other frameworks might provide lessons and good practices for future iterations of EPA’s causal determination framework. The committee identified several such systems based largely on recommendations by speakers to the committee, mentions in public comments received by the committee, prior reports of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies), and on knowledge of the committee members. While a complete review of all such systems was not possible, nine frameworks were selected for further review and comparison. Some were designed specifically for regulatory purposes, but several are intended primarily to provide trustworthy guidance to decision makers including regulatory bodies. Some of the approaches nest causal decisions within the hazard identification portion of a risk assessment process; and one was entirely a risk assessment process but provided a useful comparison for parts of the process included in ISAs. The committee examined other systems not described in this report but concluded these were inapposite for the committee’s task. They were rejected as either not corresponding to causality assessments in the same sense as the Preamble (EPA, 2015a) or they already explicitly incorporate the approaches of frameworks discussed in this chapter.

Included in this chapter are short summaries of the ISA Preamble (EPA, 2015a), modifications applied to ISAs conducted after 2015, and nine additional frameworks. The nine other frameworks or reviews summarized here vary in their objectives, although all include (at least aspects of) the evaluation of causality of effects. For effects on human health, they may examine any substance (Toxic Substances Control Act [TSCA], Office of Health Assessment and Translation [OHAT], Integrated Risk Information System [IRIS], and International Agency for Research on Cancer [IARC]) or specific air pollutants (World Health Organizaton [WHO] and Canadian Smog Science Assessment [CSSA]) or class of substances (Institute of Medicine [IOM] Vaccines) or just one type

of consumer product (e-cigarettes); or may examine solely welfare effects of air pollutants (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe [UNECE]).

These frameworks vary in their approaches to the kinds of evidence they evaluate, their approaches to searching for evidence, and in selecting the evidence to evaluate in detail. A systematic approach to the literature review (dates, search strategy, types of data) is commonly adopted, specifying a standard for inclusion of a study for evaluation and providing a set of criteria to evaluate whether an individual study warrants further evaluation. Among the frameworks that evaluate primary evidence, it is common to limit assessment to articles published in the indexed, peer-reviewed literature. Some frameworks (i.e., TSCA, WHO, IRIS, National Toxicology Program [NTP], UNECE) allow the inclusion of gray literature if considered relevant. Subsequent evaluation of the quality of individual studies, the assessment of the evidence derived from those studies, and the integration of that evidence varies primarily in the formality of the approaches adopted, the explanation of those approaches, and their documentation. Ultimate classification of the evidence into causal categories is fairly uniform, with four or five categories being the norm. In the following sections we provide an overview of how the frameworks consider various steps in the evidence synthesis and causal assessment process.

For each framework, this chapter provides a brief summary of the purpose of the framework and a description of causal categories is provided. After an initial introduction describing their purpose, the text for the summaries below is organized under the following headings:

- Types of evidence and evidence selection process

- Assessing individual study relevance and quality

- Synthesis within a line of evidence

- Synthesis across lines of evidence

- Transparency and oversight of approach to study selection, study assessment, and evidence synthesis

Although it is difficult to separate some of these in some cases (e.g., the evidence selection process often incorporates aspects of assessing individual study relevance and quality). The causal determination framework as described in the Preamble (EPA, 2015a) and as applied in later ISAs is first similarly described in this chapter for the sake of comparison, with the other frameworks listed in inverse date order. Following the summaries is a short synthesis of conclusions to be drawn from comparisons among them. Readers interested only in the conclusions may wish to avoid the somewhat repetitive nature of the following individual discussions and immediately refer to the summary; however, some of the terms used there are only defined in the individual frameworks.

PREAMBLE TO THE INTEGRATED SCIENCE ASSESSMENTS (ISAs) (2015a)

Earlier chapters of this report summarize the causal determination framework and processes as described in the Preamble to the ISAs (EPA, 2015a). The following sections briefly summarize those processes under the headings (described above) that will be used for comparison to other frameworks in later sections of this chapter.

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

EPA deliberately casts a wide net to consider any potentially relevant studies to incorporate into the causal determination, and then winnows the studies by reviewing study quality and relevance. Evidence selection and quality and relevance reviews are part of the same process. To obtain the most comprehensive initial selection of materials, the Preamble requires an initial Federal Register

call-in and specifies a continuing search using citations and journal tables of contents, references from the EPA Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC) reviews and from other experts, and incorporating all references that were included in previous ISAs on the same pollutant. The evaluation is limited to peer-reviewed and published or accepted articles and requires that the studies be ethically conducted and limited to those about or including exposure-response relations, modes of action, populations, life stages/ecosystems at risk, atmospheric chemistry, air quality and emissions, environmental fate or transport, dosimetry, toxicokinetics, or exposure. Selection is initially by title and abstract followed by full-text review, based on the extent to which studies are “informative, pertinent, and policy relevant.” Studies considered for inclusion in the ISA are to be listed in EPA’s Health and Research Online (HERO) database.1

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality

Studies are considered relevant to the ISA if they are “informative, pertinent, and policy relevant,” and particularly so if they reflect current exposure conditions, demonstrate pollutant/effect relationships, provide innovations in methodology, reduce uncertainties, provide unique data, show a new effect or new mode of action, or examine multiple concentrations.

For quality, a general approach is applied to all studies, with additional considerations applied to specific types of studies. The general approach evaluates study design, methods, conduct, and documentation. Quality considerations include clear presentation of the groups, methods, data, and results relative to the study objectives, with limitations, assumptions, and other factors clearly stated. Other general aspects include adequate documentation for evaluation, adequately selected sites, populations, and subjects within groups, adequate air quality metrics, with effects well defined and validly and reliably measured. With respect to ecosystems, sites, populations, and subjects or organisms, there should be an adequate and well-defined selection methodology, with clear distinction between exposures. Dose metrics should be of adequate quality, representative, and correspond to ambient conditions, and the effects measured should again be valid, reliable, and meaningful. In all cases, analytical methods should be adequate to support conclusions, statistical methods should be appropriate and correctly applied, and covariates adequately controlled in design and analysis. Study results should not be considered in evaluation of quality.

Further quality considerations are applied specifically to four areas: atmospheric science and exposure assessment, epidemiology, controlled human exposure and animal toxicology, and ecological and other welfare effects. For each of these areas, the Preamble provides broad descriptions of features considered in the quality evaluation and/or particularly desirable for the ISA assessment.

The Preamble provides these lists of broad quality considerations but gives no indication of how they should be measured against one another or compared between studies, leaving it to expert judgment to weight studies and account for any disagreement.

Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence

The Preamble calls for evaluation of four lines of evidence to examination of the health effects of air pollution:

- Controlled human exposures,

- Epidemiology,

- Animal toxicity/mode of action, and

___________________

1 See https://hero.epa.gov (accessed May 16, 2022).

-

In vitro studies/mode of action (not separately discussed), while for ecological/welfare effects, three lines of evidence are selected:

- Laboratory studies (controlled conditions),

- Field observations (uncontrolled conditions), and

- “Intermediate” studies (field experiments), including laboratory examination of field-collected environmental media, and field studies controlling for some (but not all) environmental or genetic variability (e.g., mesocosm experiments).

Within each line of evidence, synthesis across multiple studies is by a weight of evidence evaluation with Bradford Hill aspects of association (Hill, 1965) providing a backdrop to aid judgment, while citing multiple “formalized” approaches. There is a substantial discussion of factors to consider, but no particular methodology is specified.

Synthesis Across Lines of Evidence

The Preamble calls for an “integration of findings from various lines of evidence from across health and environmental effect disciplines that are integrated into a qualitative statement about the overall weight of the evidence and causality,” with five categories of causal determinations, each specified (separately for health effects and ecological and other welfare effects) by a descriptive paragraph (EPA, 2015a). The selection of causal category must be characterized by the evidence on which judgment is based, including the strength of evidence for individual endpoints with groups of related endpoints.

Causal determinations must be made for exposures or doses within the range of relevant pollutant exposures, so the focus is on evidence from exposures or doses at or near those currently experienced by the U.S. population. Evidence from exposures or doses by up to about 100 times higher are considered where appropriate to account for intra- and interspecies differences, while higher exposures or doses may be considered if they shed light on relevant mode(s) of action.

Transparency and Oversight of Approach to Study Selection, Study Assessment, and Evidence Synthesis

The Preamble calls for entry of references considered for inclusion in an ISA in a public repository (EPA’s HERO), and for draft ISAs to be released for review before the final ISA is published. Further information is available on many aspects of the process on the EPA website2 referenced in the Preamble. Oversight of the process is to be accomplished by public reviews of draft ISAs by a seven-member independent federally chartered scientific advisory committee (CASAC), together with a requirement to take account of public comments. For each National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) review, ad hoc panels are typically convened to support the chartered CASAC. These panels are composed of individuals with pollutant-specific expertise in the relevant disciplines.

Early in the ISA process, EPA typically convenes a peer input meeting in which the content of preliminary draft materials is reviewed by subject-matter experts to ensure the ISA is up to date and focused on the most policy-relevant findings. Further requirements for transparency and oversight may be set by regulation, and further oversight and transparency are afforded by other parts of the NAAQS review process documented in the Preamble (see Figure 1.1), such as an initial workshop and the Integrated Review Plan (IRP).

___________________

2 See https://www.epa.gov/naaqs (accessed May 19, 2022).

RECENT ISAs (2016–2020)

As described earlier in the report, multiple processes have been modified or added into the ISA process since the publication of the Preamble. These are summarized below for the purpose of comparison with the Preamble and with other causal determination frameworks.

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

ISAs published more recently than 2015 employ the general procedures identified in the Preamble, but in some cases, most notably the 2020 ozone ISA (EPA, 2020a), they have adopted a more structured and potentially more comprehensive approach. In some cases, procedures described in general terms in the Preamble are refined or described in more detail in later ISAs, adding clarity and transparency. Recent ISA approaches to searching and screening include:

- (For health effects) broad, inclusive keyword searches of titles and abstracts in relevant peer-reviewed literature databases (PubMed,3 Web of Science,4 TOXLINE5).

- (For welfare effects) references identified by topic-specific citation mapping in the Web of Science of citations from previous ISAs that are cited in more recent publications.

- For each discipline (atmospheric science, exposure assessment, experimental health studies, epidemiology, ecology, and climate-related science), the machine learning SWIFT-AS (Howard et al., 2020) tool was employed to facilitate Level 1 (title and abstract) screening and sorting to determine if there was a quantifiable effect relevant to an identified discipline and the air pollutant that was within an explicitly defined scope.

- Discipline-specific PECOS (Population, Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design) tools were developed for experimental studies, epidemiologic studies, ecological studies, and studies on the effects of tropospheric ozone on climate. These were introduced in the Ozone IRP (EPA, 2019a), and helped determine the scope of the ISA and guide the identification of relevant studies.

- For certain atmospheric and global climate science topics, recent major reviews were employed as primary references for sections of the 2020 Ozone ISA (EPA, 2020a). For example Jaffe et al. (2018) and Gaudel et al. (2018) were primary references for assessment of U.S. background ozone. The National Climate Assessment (USGCRP, 2018a), and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC, 2013) were primary references for assessment of ozone effects on climate. However, review papers are not used in making causal determinations.

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality

Studies selected in Level 1 screening are subject to full text (Level 2) screening for both relevance and quality by teams of EPA subject matter experts. The same considerations are applied as in the Preamble, but have been formalized in the 2020 Ozone ISA (EPA, 2020a) by the application of discipline-specific PECOS tools, which are used to further screen experimental studies, epidemiologic studies, ecological studies, and for studies on the effects of tropospheric ozone on climate, and to determine which individual studies are (or are not) relevant to the scope of the ISA. The PECOS tools were based on evidence supporting the causal determinations from the previous 2013 Ozone ISA (EPA, 2013a) and consideration of uncertainties and limitations of that evidence.

___________________

3 See https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed May 16, 2022).

4 See https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science (accessed May 16, 2022).

5 See https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_Report.cfm?Lab=&dirEntryID=2794 (accessed May 16, 2022).

For the most recent ozone review, the PECOS tools were presented in the IRP (EPA, 2019a), and subject to review and comment in advance of the ISA.

Since 2016, study quality criteria tables have been developed for both experimental and epidemiological health studies to provide clear descriptions of how individual health study quality will be evaluated for each discipline. No numerical rating system is applied to assess study quality, but prompting questions are developed in advance for each study domain in the study quality table, with the aim of supporting consistent reviews and narrative descriptions of study quality. While study quality criteria tables are only developed for health effects studies, similar quality criteria are also specified in recent ISAs for atmospheric science, exposure assessment and welfare effects, as described in the Preamble and enhanced in recent ISAs.

While the screening procedures for study relevance and quality in recent ISAs are similar to those generally described in the Preamble, they have become more refined or are described in greater detail in the recent ISAs (e.g., contrast Figure III from the Preamble [EPA, 2015a]—similar to Figure II in the 2013 Ozone ISA [EPA, 2013a]—with the much more quantitatively detailed “Literature Flow” Figure 10-2 from the 2020 Ozone ISA [EPA, 2020a]). As in the Preamble, lists of quality considerations are provided, but there is no indication of how they should be measured against one another or compared among studies, leaving it to expert judgment to weight studies and account for any disagreements. For health studies considered “policy-relevant” (i.e., supporting a causal or likely causal determination or supporting changes in a previous causal category), detailed narrative descriptions of the study quality reviews are recorded in EPA’s Health Assessment Workspace Collaborative (HAWC) database,6 which can be accessed from the HERO project page7 for the Ozone ISA (EPA, 2020a).

Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence

There have been no general modifications of the evidence synthesis process in ISAs after the 2015 Preamble, although more pollutant-specific evidence synthesis processes are described in individual ISAs. For example, several standardized numerical constraints were applied in the 2020 Ozone ISA (EPA, 2020a) to assure consistency in comparing and combining study results. For example:

- Risk estimates from epidemiological studies were standardized to a 15-ppb increase in the 24-hour average ozone concentration, a 20-ppb increase in the 8-hour daily maximum, a 25-ppb increase in the 1-hour daily maximum ozone concentrations, or a 10-ppb increase in the seasonal/annual ozone.

- For assessing co-pollutants or other correlated variables in epidemiologic studies, high correlations are defined (using the correlation coefficient r) as r ≥ 0.70, moderate concentrations are defined as moderate correlation, r ≥ 0.40 and r < 0.70, and low correlations are defined r < 0.40.

Synthesis Across Lines of Evidence

Recent ISAs have followed the generic procedure outlined in the Preamble, with more pollutant-specific processes described in individual ISAs. External peer reviews of draft ISAs have assisted EPA with integration of evidence within and across disciplines.

___________________

6 See https://hawcproject.org (accessed May 16, 2022).

7 See https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/project/page/project_id/2737 (accessed May 16, 2022).

Transparency and Oversight of Approach to Study Selection, Study Assessment, and Evidence Synthesis

Recent ISAs have included elements included in and beyond requirements listed in the Preamble that enhance transparency:

- All references identified for consideration, included and excluded after Level 1 screening and included and excluded after Level 2 relevance screening and quality reviews are tagged and listed in the EPA HERO database.

- For references considered policy-relevant or identifying important new advances in scientific understanding, detailed narrative quality reviews are submitted to the HAWC database, publicly accessible from the HERO project page for the ISA.8

- ISAs are developed with extensive, open peer review. Each NAAQS review is initiated by a public formal call for information, typically (but omitted in 2020 Ozone ISA) followed by an open “science and policy issue workshop” during which subject area experts and the public are asked to highlight new/emerging research and make recommendations on design and scope of the review.

- EPA peer review seeks early feedback during ISA development from subject-matter experts from within and external to EPA to ensure that the ISA is up to date and focused on the most policy-relevant findings. This is mentioned in the Preamble (EPA, 2015a), but better documented in recent ISAs, including that the review is externally managed (ICF International for 2020 ozone ISA), and that it and other aspects of the ISA peer review are conducted in accordance with the EPA Peer Review Handbook, 4th edition.9

- Enhancement of review through the reviews by CASAC expert panels and the public of two drafts for each ISA.

- Detailed narrative quality reviews of “policy relevant” studies (supporting causal or likely causal determinations or changes in causal category from previous ISA) are registered in a HAWC database, publicly accessible via HERO (for the 2020 Ozone ISA).

- For all draft ISAs, public, CASAC, and CASAC expert panel comments and EPA responses to those comments are documented and publicly accessible.

- EPA constructs, publicly documents, and follows an Internal Quality Assurance Project Plan.

TOXIC SUBSTANCES CONTROL ACT (TSCA)

The TSCA as amended in 2016 requires EPA’s Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (OPPT) to determine whether regulation is required for any new or existing chemical if the chemical poses an “unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment,” with risk evaluations required to describe the “weight of the scientific evidence” (15 U.S.C. § 2604, § 2605). Decisions are to be based on the “weight of the scientific evidence” (15 U.S.C. § 2625(i)), which term EPA defined by regulation (40 CFR 702.33). TSCA reviews comprise a full risk evaluation, accounting for exposure and dose-response information in addition to hazard identification.

EPA published guidance for TSCA systematic review and weight of evidence assessments in 2018 (EPA, 2018c). The National Academies reviewed the 2018 guidance (NASEM, 2021), recommending modifications. In response, EPA released a new draft systematic review protocol for existing chemicals, which is still subject to comments and revision (EPA, 2021). The protocol is

___________________

8 See, for example, https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/project/page/project_id/2737 (accessed May 16, 2022).

9 See https://www.epa.gov/osa/peer-review-handbook-4th-edition-2015 (accessed May 16, 2022).

similar to the ISA causal determination framework in that it includes evaluation of causality in a hazard identification and also evaluates chemical properties, fate, and human exposures and risks.

The classification of weight of evidence for causation adopted in the TSCA draft systematic review protocol (EPA, 2021) has four categories for causation of environmental health hazards that may be summarized as:

- Evidence demonstrates that there is the environmental health outcome Y with relevant chemical X exposures.

- Evidence indicates there is likely an association between the environmental health outcome Y with relevant chemical X exposures.

- Evidence is inadequate to determine a relationship between the environmental health outcome Y with relevant chemical X exposures.

- Strong evidence supports no association between environmental health outcome Y with relevant chemical X exposures.

For human health, the TSCA draft systematic review protocol (EPA, 2021) has five categories for causation that may be summarized as:

- Evidence demonstrates that chemical X causes health effect Y in relevant exposure circumstances.

- Evidence indicates that chemical X likely causes health effect Y in relevant exposure circumstances.

- Evidence suggests but is not sufficient to conclude that chemical X may cause health effect Y in relevant exposure circumstances.

- Evidence is inadequate to assess whether chemical X exposure may cause health effect Y in relevant exposure circumstances.

- Strong evidence supports no effect in humans from chemical X exposures in relevant exposure circumstances.

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

Literature search and screening strategies are more extensively described in the TSCA draft protocol than in any other of the frameworks examined by the committee, partly because the search covers not only human and environmental hazard assessments, but also physical/chemical properties, fate and transport, occupational and other exposure, and environmental releases. Searches include databases of peer-reviewed literature, gray literature (a catchall category, including non-peer-reviewed material), data submitted under TSCA regulations, backward searches from literature citations, and references from public comments submitted during the process. The types of evidence searched for depend on the hazards evaluated. For environmental hazards, three lines of evidence are examined—apical endpoints (endpoints with potential population-level effects), mechanistic data, and community-level effects from field studies. For potential human health effects, lines of evidence are studies in humans, studies in animals, and mechanistic information.

The screening approach for peer-reviewed literature is a four-step process. Step 1 is the search using the chemical name, synonyms, and identifiers; search results are stored in EPA’s HERO database. Step 2 uses SWIFT-Review software10 (Howard et al., 2020) to categorize and filter references into separate disciplines using keyword filters. Step 3 screens the titles and abstracts of filtered studies according to relevance criteria (pre-derived PECO [Population, Exposure, Com-

___________________

10 See https://www.sciome.com/swift-review (accessed May 16, 2022).

parator, and Outcomes] statements for hazard and exposure studies, and comparable statements for other objectives) using SWIFT-Active Screener11 (Howard et al., 2020) or DistillerSR.12 Step 4 then involves full-text screening using DistillerSR. Gray literature goes through a pre-screening step involving a decision logic tree to evaluate relevance, remove duplication, and handle confidential information before application of discipline-specific PECO full-text screening.

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality

Assessment of individual study relevance was performed during the evidence selection process, as summarized above. The TSCA draft indicates that the study quality evaluation protocol was largely influenced by the IRIS Handbook (EPA, 2020c), although multiple sources were examined. Each study is evaluated for quality on a set of domains specific to the type of study—for example, animal toxicity study domains are test substance, test design, exposure characterization, test organism, outcome assessment, confounding/variable control, data presentation and analysis, and other (a catchall for specific circumstances). Each domain contains a set of metrics intended to assess an aspect of methodological quality, sensitivity, risk of bias, or lack of reporting. To evaluate each metric, criteria are defined based on professional judgment and existing systematic review frameworks. A data quality ranking with range 1 to 3 (high, medium, low), critically deficient, or not applicable is assigned to each relevant metric within a domain, and the average rank of all applicable metrics in a study is calculated to obtain an overall quality category of high, medium, or low (dividing the possible range of averages equally), or uninformative (critically deficient in at least one metric). Each data quality ranking for each metric is explained in tabulations. Studies with critical deficiencies may be used for some purposes, depending on the domain with the deficiency—for example, a study that is uninformative for dose-response may be informative and used as support for hazard evaluation. Data quality evaluation using this approach is tracked and recorded in DistillerSR, with an initial reviewer assigning quality ranks then a second assessor providing a quality review of the first, with both recorded in DistillerSR, and further comments encouraged and documented. Conflicts are resolved by discussion, and reviewers are trained and calibrated on common materials. The study quality ranking may be adjusted using professional judgment, but the reviewer would require a compelling reason for such a change.

Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence

In contrast to the highly prescriptive approaches described above for search and quality evaluation, the protocol leaves evidence integration primarily to professional judgment guided by pre-defined hierarchies. Evaluation of the strength of evidence is first done within evidence streams and then across evidence streams. Modified considerations adapted from those of Bradford Hill aspects of association (Hill, 1965) guide the determination of whether a causal relationship has been demonstrated. For environmental hazards, the modified considerations are quality of the database (risk of bias), consistency, strength (effect magnitude) and precision, biological gradient/dose response, biological relevance, physical and chemical relevance, and environmental relevance (EPA, 2021, Table 7-10). Strength of the evidence is summarized for in vivo apical endpoint studies in plants or animals, mechanistic studies, and field/mesocosm studies (EPA, 2021, Table 7-11). Overall weight of the evidence for causal determinations are categorized as “evidence demonstrates,” “evidence indicates likely,” “evidence is inadequate,” and “strong evidence supports no effect” (EPA, 2021,

___________________

11 See https://www.sciome.com/swift-activescreener (accessed May 16, 2022).

12 See https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software (accessed May 16, 2022).

Table 7-12). The descriptions provided for these categorizations are very similar to those used for welfare effects in the 2015 Preamble, with the “suggestive of but not sufficient” category excluded.

For human health, the strength of the evidence is first assessed separately for human studies, animal studies, and mechanistic studies, considering database quality, consistency, magnitude and precision, biological gradient/dose response, and biological plausibility (EPA, 2021, Table 7-13 and Figure 7-4). Strength of the evidence is characterized as “robust,” “moderate,” “slight,” “indeterminate,” or “compelling evidence of no effect.” The appropriate descriptor is selected on the basis of the judgment of “human health assessors,” with the judgment of each evidence stream presented in an “evidence profile table” (EPA, 2021, Table 7-15).

Synthesis Across Lines of Evidence

Judgments are drawn for the weight of evidence across evidence streams, based on coherence across evidence streams and giving the greatest weight to human evidence followed by evidence in animals and then mechanistic evidence. In contrast to the environmental hazards categorizations, five categories are used for human health effects, adding the middle category of “evidence suggests but not sufficient.” Combinations of strength of evidence assessments for human, animal, and mechanistic evidence streams that support each classification are provided in table form in the protocol (EPA, 2021, Table 7-14), although these combinations are characterized as guidance rather than prescriptions.

Transparency and Oversight of Approach to Study Selection, Study Assessment, and Evidence Synthesis

The TSCA protocol calls for extensive documentation in evidence collection, selection, and review. The collection and selection phase is to be recorded in EPA’s HERO, which is public; however, the review material is to be recorded in DistillerSR, and no information is provided in the protocol on access to the resulting database. Similarly, while the evidence synthesis implicitly or explicitly requires documentation of the steps involved (e.g., the preparation of the evidence profile table [EPA, 2021, Table 7-15]), the protocol is silent on how that documentation is to be maintained and provides no direction on access to any such documentation, although presumably most such documentation would appear in an EPA publication supporting a TSCA Risk Evaluation. The only oversight indicated in the protocol is internal to the entire assessment, with no specification of any external oversight.

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO)

WHO periodically issues and revises health-based air quality guidelines (AQGs) based on dose-response assessment to assist governments in reducing human exposure to air pollution and its adverse effects. The most recent WHO global AQGs (WHO, 2021) are for particulate matter (PM)2.5, PM10, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide, set at the lowest levels of exposure for which there is evidence of adverse health effects. The guidelines were developed following principles specified in the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development (WHO, 2014). WHO focused on outcomes for which causal or likely causal determinations had been determined in EPA ISAs, Canadian health assessments, and other publications. Thus, while the WHO guidelines do not contain a causal assessment, they do contain many of the requirements of such an assessment so are included here. The first three steps in the WHO process are formulation of the scope and key questions of the guidelines, systematic review of the relevant evidence, and assessment of the certainty level of the body of evidence resulting from systematic review.

WHO originally used five categories for causal description, but the document examined is restricted to examination of endpoints considered (by prior publications) to be causal, likely causal, or suggestive. For each derived guideline quantity for a pollutant/endpoint pair, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) review framework categorizes quality as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

The WHO evaluation process was initiated by a Guideline Development Group of external subject-matter experts who select priority pollutants (PM10, PM2.5, O3, NO2, SO2, CO) and prioritize health outcomes (based on prior Health Canada, EPA ISAs, and IARC evaluations). The focus of the evaluation is on causal, likely causal, and suggestive (if the outcome is severe) effects of the pollutants, with critical health outcomes selected as all-cause mortality, cause-specific mortality, hospital and ER visits due to asthma, and hospital and ER visits due to ischemic heart disease.

The approach was to identify critical pollutant-specific health outcome combinations and develop population, exposure, comparator, outcome, and study design (PECOS) questions for each critical pollutant, health outcome, study type, and averaging time combination. The PECOS questions were developed to screen short-term and long-term exposures studies, providing specific criteria for inclusion or exclusion, with an initial screen of titles and abstracts and a full text screen prior to inclusion. The screening was performed separately for each combination of pollutant and outcome included. References in included articles, and citations to them, were also screened for potential inclusion.

A preliminary literature search was conducted to identify available systematic reviews and meta-analyses on air quality and health, and such reviews were updated if necessary and feasible. The general literature search methods used are documented in the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development, 2nd edition.13 Specific literature search methods and databases are described for systematic reviews carried out for each critical pollutant/health outcome, selecting peer-reviewed articles in any language (provided abstracts were available in English) and published or accepted for publication, together with gray studies not indexed in commercial bibliographic database if considered relevant. The systematic reviews are summarized in WHO (2014) Annex 3 and are registered in PROSPERO.14

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality

The WHO Air Quality Guidelines (WHO, 2021) contains a comprehensive chapter detailing features of the systematic review of evidence as well as assessment of the quality of evidence obtained in the systematic review. Of note, their systematic review search and quality assessment involves different groups of people with defined roles and responsibilities and includes ample opportunity for outside expert feedback in the process, including dedicated teams for risk of bias assessment and for assessment of the “certainty of evidence” (explained below under “Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence”). Protocols for each systematic review are public and registered in the PROSPERO registry. Risk of bias is assessed based on a publicly available instrument developed a priori. This instrument explicitly states the criteria for risk of bias used (confounding, selection bias, exposure assessment, missing data, and selective reporting).

In the WHO approach, relevance is predetermined by responsiveness to the PECOS questions. Risk of bias was assessed for confounding, selection bias, exposure assessment, outcome measure-

___________________

13 See https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/145714 (accessed May 16, 2022).

14 See https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO (accessed May 16, 2022).

ment, missing data, and selective reporting, and is assessed separately for randomized controlled trials, nonrandomized trials, and observational studies. Factors specified as lowering confidence in individual study results include limitations in study design or execution, indirectness (study divergence from PECOS requirements), and imprecision, while factors specified as increasing confidence in individual study results include a dose-response gradient, the direction of plausible bias, and the magnitude of effect observed.

Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence

The WHO evidence synthesis evaluation was strictly aimed at evaluating guidelines for specific health effect endpoints already classified regarding causality (WHO, 2021, Table 2.1). However, the last step of the formulation of long-term guidelines (WHO, 2021, Table 2.5) involved reconsideration of the causal classification, so the procedures were presumably designed to account for this. The PECOS formulation limited evaluation to epidemiological studies, the only research approach considered. For each study, relative strengths and weaknesses and degree of confidence were assessed. For each endpoint, meta-analyses to obtain pooled estimates of risk for adverse health outcomes per unit increase in exposure to a given air pollutant were conducted or updated if three or more pollutant/effect studies were available. Statistical analyses were consistent with Blair et al. (1995), Higgins and Green (2011), and other authoritative guidance. Systematic reviews could be combined for health endpoints common to multiple pollutants (e.g., NO2 and O3 and all causes of respiratory mortality). The systematic reviews followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines15 and are published (Whaley et al., 2021). Confidence ratings were obtained for each pollutant/health endpoint using a GRADE (Schünemann et al., 2013) approach modified for use on epidemiological studies, using five factors to downgrade and three factors to upgrade the quality of evidence:

- Downgrade: limitations in study design or execution, inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision, publication bias (even if published studies show low risk of bias).

- Upgrade: large effect, all plausible confounding would either increase or decrease effect if none observed, dose/response gradient.

Risk of bias was assessed with the WHO Risk of Bias (RoB) tool for six key domains (confounding, selection bias, exposure assessment, outcome measurement, missing data, selective reporting). Within GRADE, randomized controlled trials started at high certainty; nonrandomized studies started at low certainty, and then each study was downgraded or upgraded as indicated above. The final GRADE rating was not used for causal evaluation, but to evaluate the certainty associated with the final air quality guideline.

Synthesis Across Lines of Evidence

Not applicable; only one research approach considered (see above).

___________________

15 See http://www.prisma-statement.org (accessed May 16, 2022).

Transparency and Oversight of Approach to Study Selection, Study Assessment, and Evidence Synthesis

The procedures adopted most recently are clearly summarized in the 2021 WHO Air Quality Guidelines (WHO, 2021). Summaries of the systematic review methods for all pollutant/endpoint pairs are summarized in Annex 3 of the Guidelines, with links to detailed reviews registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews), and published in an open access issue of Environment International (Whaley et al., 2021). However, the details are not always clear or necessarily reproducible, and the present study committee cannot find ready public access to any document(s) other than the final Guidelines. Oversight is afforded by “several rounds” of internal and external review, where the External Review Group included both invited “experts” from 31 countries, 65 of whom provided input, and 72 invited stakeholder groups, 14 commenting. The External Review Group review focused on identifying missing data, unclear information, factual errors, implementation issues, but not on changing recommendations.

INTEGRATED RISK INFORMATION SYSTEM (IRIS)

EPA maintains the IRIS16 program to develop risk assessments for chemicals in the environment. IRIS health assessments emphasize hazard identification and dose-response analyses and are used for both EPA risk assessment processes and by outside organizations. Like the ISA process, IRIS health assessments are used in determining regulatory priorities and are subject to public review and scrutiny by interested parties. Causal assessments are included in the hazard identification component of the IRIS assessment process, and require similar data extraction, synthesis, and causal determinations as the Preamble’s framework process. The IRIS process has been changing in response to criticism, and the draft considered in this report (and here called the IRIS Handbook) was published in 2020 (EPA, 2020c). That draft itself was the subject of a National Academies’ review published in 2022 (NASEM, 2022). The assessments result in selection of one of five categories of causality:

- Evidence demonstrates that chemical X causes health effect Y in humans under relevant exposure circumstances.

- Evidence indicates that chemical X likely causes health effect Y in humans under relevant exposure circumstances.

- Evidence suggests that chemical X may cause health effect Y in humans under relevant exposure circumstances.

- Evidence is inadequate to assess whether chemical X causes health effect Y in humans under relevant exposure circumstances.

- Strong evidence supports no effect in humans under relevant exposure circumstances.

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

The multidisciplinary team charged with an IRIS assessment must go through a scoping/problem formulation stage including design and implementation of a systematic review process. This process includes constructing PECO criteria that will be addressed in the assessment. Studies are to be located by searches of PubMed, Web of Science, EPA’s CompTox Chemicals Dashboard17 and

___________________

16 See https://www.epa.gov/iris (accessed May 16, 2022).

17 See https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard (accessed May 16, 2022).

Chemview,18 and NTP 2-year rodent bioassays.19 Supplemental databases are searched depending on topic (including AEGLs,20 Agricola,21 ChemIDPlus,22 DTIC,23 J-CHECK,24 FIFRA submission databases25), together with literature searches in specific services using specific keywords. In addition, regulatory submissions are searched for pertinent information. The aim is to obtain full reports of “Primary Studies” that are screened into the procedure following the PECO criteria, using primarily peer reviewed publicly accessible literature but also including all the previously identified sources including gray literature and non-peer-reviewed material if relevant to the PECO criteria. Non-peer-reviewed material may be included if it can be peer-reviewed by EPA-contractor-selected external reviewers, and the details and results made publicly accessible. The search is to be updated to no earlier than 1 year prior to publication of the final assessment.

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality

The IRIS Handbook does not pre-specify any aspects of a study that are required or recommended in evaluation of relevance, but it is clear that some studies will be determined to be of poor quality and hence excluded or considered not influential. Such studies, likely to be relegated to the “supplemental” category, include studies in nonmammalian models systems, toxicokinetic or pharmacokinetic studies, exposure characterization studies, mixture studies (unless epidemiological), and human case reports or case series.

For study quality, evaluation domains are specified, with criteria. Evaluation is by two reviewers with a conflict resolution process. Overall study quality is categorized as high, medium, low, or uninformative. Key study evaluation concerns are reporting quality, risk of bias, and study sensitivity. Quality evaluation criteria are evaluated separately for epidemiology, controlled human exposure, animal, and mechanistic studies, although there is limited discussion of controlled human exposure studies. The IRIS Handbook lists specific criteria to be evaluated for epidemiology and toxicology studies. There are no specific criteria listed for mechanistic studies, but it is recommended that the same criteria as listed for epidemiology and toxicology studies be used for human and animal studies reporting mechanistic outcomes. For in vitro studies, it is acknowledged that development of quality evaluation methods lags, but suggestions are provided.

Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence

The IRIS Handbook documents three lines of evidence to be considered:

- Epidemiology

- Animal experimental and Human controlled exposure studies

- Mechanistic (used in primarily supportive role)

While no particular method of evaluation is proposed, there is extensive discussion of aspects of the studies to be considered in evaluation of each line of evidence. For human and experimental animal studies, the Bradford Hill aspects of association (Hill, 1965) are listed as a general frame-

___________________

18 See https://chemview.epa.gov/chemview (accessed May 16, 2022).

19 See https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/publications/reports/index.html?type=Technical+Report (accessed May 19, 2022).

20 See https://www.epa.gov/aegl (accessed May 16, 2022).

21 See https://agricola.nal.usda.gov (accessed May 16, 2022).

22 See https://chem.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus (accessed May 16, 2022).

23 See https://www.dtic.mil/DTICOnline (accessed May 19, 2022).

24 See https://integbio.jp/dbcatalog/en/record/nbdc01383 (accessed May 16, 2022).

25 Accessible only to certain U.S. government employees.

work for synthesis. Where possible, formal combination (e.g., by meta-analysis, taking account of publication bias) is proposed, but when few studies are available an individual discussion is recommended. Additional considerations applied to animal evidence include exposure ranges evaluated, toxicokinetic differences between species, sensitivity of the studies, and comparisons of endpoints evaluated. Mechanistic evidence is evaluated to identify the strength of evidence for potential key events and modes of action and the relevance of those to the human and animal experimental results. Human and experimental animal studies are specified to be evaluated also in the light of the mechanistic study results.

Analyses of risk of bias and sensitivity (across studies), consistency, effect magnitude and precision, biological gradient, coherence, and biological plausibility (each provided with one or more reasons for increased or decreased strength or certainty) for human and animal studies are used to judge the overall strength of evidence for effects as robust, moderate, slight, indeterminate, or compelling for no effect, with descriptors of these terms provided (EPA, 2020c, Tables 11-3 and 11-4).

Synthesis Across Lines of Evidence

For evidence integration, the IRIS Handbook prescribes a near-deterministic approach to specifying the overall causal category for specific health effects in humans, based on the strength of evidence classifications (robust, moderate, slight, indeterminate, or compelling for no effect) in humans and animals. Table 7.1 summarizes the overall schema, with italic entries indicating possibilities dependent on further information on uncertainties or mechanisms as described in the IRIS Handbook (so human/animal pairs of entries may appear in more than one row).

TABLE 7.1 Summary Schema for IRIS Strength of Evidence Classificationsa

| Overall Causal Judgment | Human Evidence | Animal Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence demonstrates | Robust | Unnecessary |

| Moderate | Robust | |

| Evidence indicates | Slight-to-indeterminate | Robust |

| Moderate | Robust | |

| Moderate | Slight or indeterminate | |

| Slight or indeterminate | Moderate | |

| Evidence suggests but is not sufficient to infer | Slight | Indeterminate-to-slight |

| Indeterminate-to-slight | Slight | |

| Moderate | Slight or indeterminate | |

| Slight or indeterminate | Moderate | |

| Evidence inadequate | Indeterminate | Indeterminate |

| Compelling evidence of no effect | Slight | |

| Indeterminate | Compelling evidence of no effect | |

| Indeterminate | Slight-to-robust | |

| Strong evidence supports no effect | Compelling evidence of no effect | Compelling evidence of no effect |

| Indeterminate | Compelling evidence of no effect | |

| Compelling evidence of no effect | Moderate-to-robust |

a Italic entries indicate possibilities dependent on further information on uncertainties or mechanisms as described in the IRIS Handbook.

SOURCE: Based on Table 11-5 of the IRIS Handbook.

Transparency and Oversight of Approach to Study Selection, Study Assessment, and Evidence Synthesis

The Handbook in its illustration of the process states that “although public input and peer review are not depicted, they are viewed as integral components of the IRIS process.” All data used must be publicly accessible (or is made publicly accessible during the process) and is tracked through documentation in HERO. The initial IRIS Assessment Plan is to be presented at a Public Science Meeting to solicit input, and that Plan and the subsequent Assessment Protocol documents are to be made available with at least a 30-day public comment period, and the Draft Assessment document with typically a 60-day public comment period. Protocols and updates are to be published on the IRIS website,26 and protocols or updates should include literature screening results. Software tools used within IRIS are to be publicly available (and free when possible), including the EPA HAWC,27 which is used for study evaluation and data extraction. There is not documentation of any requirement for a formal external expert review of the final document, except that provided by public review comments. In principle, EPA internal documents may be obtained by Freedom of Information Act28 request.

OFFICE OF HEALTH ASSESSMENT AND TRANSLATION (OHAT)

The OHAT of the NTP under the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) recently developed a handbook to guide systematic review and evaluation of hazard assessment evidence for substances of interest, leading to NTP “Level of Concern” conclusions. NTP assessments are advisory to the public and to federal and state regulatory agencies, including EPA. The OHAT Handbook (NTP, 2019) calls for conclusions to be described in terms of the strength of the evidence for associations between a substance and the health endpoints of interest, but unlike ISAs does not evaluate exposures or describe dose-response relationships. As in ISAs, the assessment of the strength of associations includes the Bradford Hill aspects of association (Hill, 1965). The OHAT Handbook is considered a “living document;” an initial version was reviewed by the National Academies (NASEM, 2020). The conclusion of the hazard assessment is selected to be one of five possibilities:

- Known to be a hazard to humans

- Presumed to be a hazard to humans

- Suspected to be a hazard to humans

- Not classifiable as a hazard to humans

- Not identifiable as a hazard to humans

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

As for the IRIS process, evidence gathering is preceded by a scoping and problem formulation and protocol development, with study questions defined through a PECO statement (Step 1 of the OHAT Handbook process). The literature search and screening process (Step 2 of the Handbook process) is developed as part of the protocol, with literature searches to include any journals, searches in specific services with specific keywords, regulatory submissions, a public request for relevant materials, and updates on prior search results including evaluation of reference lists and

___________________

26 See www.epa.gov/iris (accessed May 16, 2022).

27 See https://hawcprd.epa.gov/portal (accessed May 16, 2022).

28 See https://www.foia.gov (accessed May 16, 2022).

citations. The OHAT Handbook makes special note of inclusion of opportunities for the public, researchers, and other stakeholders to identify relevant studies that may have been missed, and a list of included/excluded studies is published once screening is completed. The search approach is expected to be documented in sufficient detail that it could be reproduced, and the date when the search will be closed is specified in advance, typically 6 weeks before planned release of a draft assessment.

The aim is to identify original data, so reviews and commentaries may be excluded except for purposes of identifying relevant studies. The NTP only evaluates peer-reviewed studies but can obtain peer-review for relevant unpublished studies, such as gray literature and dissertations. Unpublished data can be used as a supplement to published studies if the data are made publicly available. Allowing inclusion of unpublished studies (after peer review) is seen as a step toward addressing publication bias. Non-English publications may be included if title and adequate abstract are available in English.

Search and selection is constrained by the PECO criteria, and there is an explicit requirement for the use of a “web-based, systematic review software program with structured forms and procedures,” such as DistillerSR,29 litstream,30 or HAWC.31 Screening is by at least two reviewers at the title and abstract stage, followed by full text review of studies passing that initial stage.

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality

In the OHAT approach, relevance is part of the study selection step (summarized above) and is guided by PECO criteria defined in advance for a particular review. Reasons for exclusion, including lack of relevance, are documented in a “study flow diagram.” OHAT also assesses “directness and applicability” with respect to the overall body of evidence. The OHAT Handbook states that “directness refers to the applicability, external validity, generalizability, and relevance of the studies in the evidence base in addressing the objectives of the evaluation” (NTP, 2019). Relevance of animal models to humans, and the route of administration are key aspects of directness, while studies generally should not be down-weighted due to exposure level or dose level since the framework is for hazard identification (prior to integration with exposure to assess risk).

For evaluation of study quality (Step 4 of the Handbook process, Step 3 being extraction of data from the studies for use in the quality evaluation), OHAT has its own risk of bias tool that is consistent with other recent guidance or approaches. Different questions are articulated for experimental animal, human controlled, cohort, case-control, cross-sectional, and case series studies. Risk of bias is evaluated on a 4-point scale from ++ (definitely low risk of bias), + (probably low risk of bias), – or NR (probably high risk of bias or insufficient information), to – (definitely high risk of bias). Actual decisions on exclusion/inclusion of studies based on study quality are to be decided on a project-specific basis, and more than one strategy may be used. Studies may be excluded in the selection phase using the PECO criteria, or a strategy may be adopted that cumulates the risk of bias from the various bias domains in some project-specific way—the OHAT manual gives an example in which the bias domains are cumulated to provide an overall three-tier evaluation.

Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence

The current OHAT Handbook focuses on evaluation of:

___________________

29 See https://www.evidencepartners.com (accessed May 19, 2022).

30 See https://www.icf.com/technology/litstream (accessed May 19, 2022); previously called DRAGON.

31 See https://hawcproject.org (accessed May 19, 2022).

- Epidemiology,

- Human and animal experimental studies, and

- In vitro studies,

but indicates that guidance for systematic review of mechanistic studies is currently in development. Within each research approach the Handbook suggests considering a meta-analysis (at least for human and animal studies), depending on study heterogeneity, and largely following the Navigation Guide approach (Koustas et al., 2014; Lam et al., 2014; Woodruff and Sutton, 2014). Sensitivity analysis of any meta-analysis results is recommended. Whether or not meta-analysis is used, confidence ratings are assigned to associations between exposure and outcome considering the body of evidence, using an approach that is based on GRADE but refined to accommodate observational studies and the need to integrate animal and in vitro studies. For human and animal studies,

available studies on a particular outcome are initially grouped by key study design features, and each grouping of studies is given an initial confidence rating by those features (Figure 6). This initial rating (column 1) is downgraded for factors that decrease confidence in the results (risk of bias, unexplained inconsistency, indirectness or lack of applicability, imprecision, and publication bias) and upgraded for factors that increase confidence in the results (large magnitude of effect, dose response, consistency across study designs/populations/animal models or species, and consideration of residual confounding or other factors that increase our confidence in the association or effect). (NTP, 2019, p. 47)

Details are provided on evaluation of the initial confidence rating of the common study design, and guidance on aggregation of the risk of bias results across studies and the other factors, together with how they affect the initial confidence rating. The synthesis across studies of the same type is reported in terms of a level of confidence (four classifications, from very low [+] to high [++++]) in associations between exposures and outcomes. To account for multiple study types and outcomes, “conclusions are primarily based on the evidence with the highest confidence.”

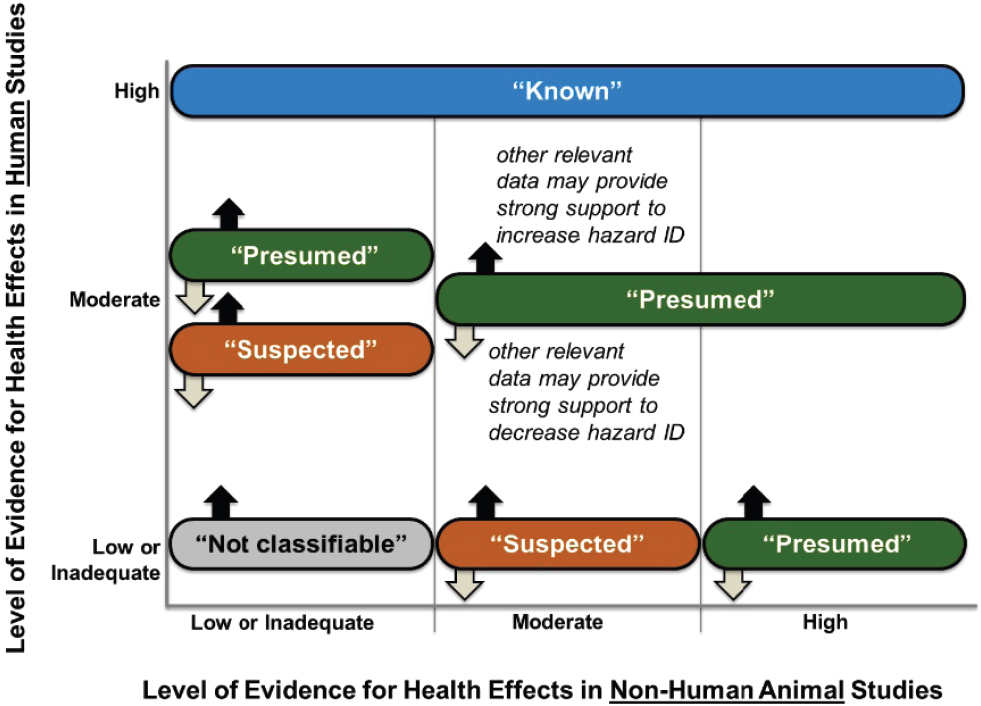

Synthesis Across Lines of Evidence

In Step 6 of the OHAT Handbook process, the confidence ratings for associations between exposures and outcomes obtained in Step 5 are translated into levels of evidence (high, moderate, low, inadequate, and “evidence of no health effect”) using a table that depends on the direction of the outcome (health effect or no health effect). The confidence ratings are for associations, but causality is implied by the inclusion of the Bradford Hill aspects of association (Hill, 1965) in the modified GRADE schema used to derive the confidence ratings. The levels of evidence obtained for human and animal evidence streams are then combined (Step 7) into five categories (known, presumed, suspected, not classifiable, and not identified; as a hazard to humans in each case). Only if there is a high level of evidence of no health effect in human studies, and this is supported by the evidence from animal data, is the last (not identified) applied. Otherwise, the four other categories are defined by Figure 7.1, although any entry except “known” may be moved up or down by consideration of mechanistic data.

Transparency and Oversight of Approach to Study Selection, Study Assessment, and Evidence Synthesis

The Handbook calls for public comment at every stage. Initially NTP solicits public comment on the nomination of a substance or topic for evaluation. A concept document is prepared and posted for public comment and reviewed by the NTP Board of Scientific Counselors in a public

SOURCE: NTP, 2019.

meeting. Subsequently the protocol for the evaluation is prepared and posted on OHAT’s website, updated at key milestones, and submitted to “relevant protocol repositories.” Once literature screening is complete, lists of included and excluded studies are posted on the project’s website32 for public review for missing studies, with a second such opportunity when the draft OHAT monograph is disseminated for public comment.

Only publicly accessible, peer-reviewed information is included, although NTP may obtain external peer review of non-peer-reviewed studies if they can be made publicly accessible. Unpublished data can supplement peer-reviewed studies, again provided the data is made publicly available. Data extracted from studies are made publicly available when the draft OHAT monograph is released and is transferred to the public NTP Chemical Effects in Biological Systems database33 on completion of the evaluation. Draft OHAT evaluations are peer-reviewed either by a peer-review panel (with public meeting and public comments) or via a letter review (ad hoc reviewers), with the results presented to the NTP Board of Scientific Counselors. The final OHAT monograph is then published.

___________________

32 See http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/evals (accessed May 16, 2022).

33 See http://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/databases/cebs (accessed May 16, 2022).

Tables and graphical displays are preferred for the final monograph to reduce text volume, with detailed risk of bias information for individual studies presented in appendix tables as documented in Appendix 4 of the Handbook (NTP, 2019). However, the Handbook is unclear on whether, how, or to what extent all the other individual steps and decisions made in development of the monograph are to be documented or made publicly accessible.34

INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER (IARC)

The WHO IARC has a longstanding program for the review and evaluation of carcinogenic hazards based on an established consensus-based process. Those reviews, published in their Monograph series,35 are designed to be advisory to risk assessments conducted by national and international authorities and organizations. The process for assessing each agent as a potential cancer hazard is analogous to the ISA causal determination process.

The recently amended IARC Monographs Preamble (IARC, 2019) describes the process for determining causality, in this case identification of “agents”—chemicals or processes combined with exposure circumstances—carcinogenic to humans. Approximately every 5 years, IARC solicits nominations of agents, an invited advisory group recommends a subset from among the agents, and IARC selects agents from that subset for review in an IARC Monograph. A panel of experts reviews information on the selected agents and develops written reviews that are published in an IARC monograph. The IARC Preamble framework differs from the ISA causal determination framework in that it provides a specific approach to determining in which causal category an agent resides by integration of streams of evidence about cancer in humans, cancer in experimental animals and mechanistic evidence. The causal determination is limited to evaluation of carcinogenic potential only. IARC places carcinogenic potential into one of four categories:

- Group 1: Carcinogenic to humans

- Group 2A: Probably carcinogenic to humans

- Group 2B: Possibly carcinogenic to humans

- Group 3: Not classifiable as to carcinogenicity to humans

although historically a fifth category (Group 4 carcinogen) was included (e.g., the 1991 and 2006 IARC Preambles [IARC, 1991, 2006]). This category—“The agent is probably not carcinogenic to humans”—was similar to the “not likely” category in the ISA causal determination framework. It is not included in the 2019 IARC amended Preamble, perhaps because the current IARC process identifies agents for review “if there is potential human exposure and there is evidence for assessing its carcinogenicity.”

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

In assessments of any material, the IARC follows a protocol set out in the IARC Preamble that includes selection of a working group to perform the assessment. The IARC Preamble calls for literature search via biomedical databases together with a public call for data, updates (citations and reference lists) on prior search results, and input from the working group via any method. The search is aimed to find information relevant to cancer in humans or in animals potentially caused by the agent, together with any mechanistic information indicating the agent may have key characteristics of established carcinogens. The object of the search is to find all such publicly available

___________________

34 Note: The peer-review panel and the NTP Board of Scientific Counselors are federally chartered advisory groups.

35 See https://monographs.iarc.who.int (accessed May 16, 2022).

material that has sufficient information to determine adequacy of reporting, quality, and results. Unpublished material from regulatory authorities may be used, provided it is publicly available.

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality

In the IARC process, three lines of evidence are examined—human studies, animal studies, and mechanistic studies. Relevant studies have in common a requirement to specify exposure concentrations and timing. They will be studies of cancer, or of benign tumors, pre-neoplastic lesions, malignant precursors, and other endpoints are considered for relevance. Relevant human studies will be epidemiological (cohort, case-control, ecological, intervention, and, rarely, case reports or series), randomized, or possibly some other innovative design. Relevant animal studies will be conventional long-term bioassays, possibly alternatives (e.g., genetically engineered mouse models), and, sometimes, other types are supportive (e.g., initiation-promotion, precancerous lesions, non-laboratory animals). Mechanistic studies may include topics such as absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME), evaluation of key characteristics of carcinogens and other informative evidence “when it is judged by the Working Group to be relevant to an evaluation of carcinogenicity and to be of sufficient importance to affect the overall evaluation” (IARC, 2019, p. 28).

In evaluation of quality, the IARC Preamble provides various listed study aspects that should be considered by the Working Group, with separate lists for human, animal, and mechanistic studies, although no scoring procedure is indicated.

Synthesis Within a Line of Evidence

The IARC Preamble calls for evaluation of any and all cancer or cancer-related endpoints using three lines of evidence (called “streams of evidence” in the Preamble):

- Epidemiologic

- Experimental animal studies

- Mechanistic

Within each approach, synthesis is by means of a weight of evidence discussion, taking account of the Bradford Hill aspects of association (Hill, 1965). Heterogeneity among studies is to be considered, with account taken of potential biases including publication bias and where appropriate and possible, meta-analysis or pooled analysis is used. Each research approach is to be categorized according to a preset schema.

For human and animal studies:

- Sufficient evidences of carcinogenicity

- Limited evidence of carcinogenicity

- Inadequate evidence regarding carcinogenicity

- Evidence suggesting lack of carcinogenicity

For mechanistic studies there are subgroups within the main schema:

- Strong mechanistic evidence

- Strong evidence that the agent belongs to a class of agents, one or more of which have been classified as carcinogenic or probably carcinogenic to humans

-

Strong evidence that the agent exhibits key characteristics of carcinogens

- Strong evidence in exposed humans

- Strong evidence in human primary cells or tissues

- Strong evidence in experimental systems

- Strong evidence that the mechanism in experimental animals does not operate in humans

- Limited mechanistic evidence

- Inadequate mechanistic evidence

Each category includes an explanation providing further guidance.

Synthesis Across Lines of Evidence

Overall synthesis across the three lines of evidence (human, experimental animal, and mechanistic) is performed automatically using Table 7.2 relating the categories established for each research approach to the final classification, which are:

Group 1: The agent is carcinogenic to humans

Group 2A: The agent is probably carcinogenic to humans

Group 2B: The agent is possibly carcinogenic to humans

Group 3: The agent is not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans

Transparency and Oversight of Approach to Study Selection, Study Assessment, and Evidence Synthesis

The IARC Preamble contains minimal requirements for transparency and none for oversight. IARC solicits nominations of agents for review and posts a list of those to be reviewed about a year in advance, with a call for data and for experts, and provides a Request for Observer Status and Declaration of Interests form. In advance of a Monographs meeting, the list of meeting participants is posted together with a summary of declared interests (and a statement discouraging contact of the Working Group by interested parties). After a Monographs meeting, a summary of evaluations and key supporting evidence is published, followed later by a final Monographs volume.

TABLE 7.2 Integration of Streams of Evidence in Reaching Overall Classificationsa

| Stream of Evidence | Classification Based on Strength of Evidence | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence of Cancer in Humansb | Evidence of Cancer in Experimental Animals | Mechanistic Evidence | |

| Sufficient | Not necessary | Not necessary | Carcinogenic to humans (Group 1) |

| Limited or Inadequate | Sufficient | Strong (c)(1) (exposed humans) | |

| Limited | Sufficient | Strong (c)(2–3), Limited, or Inadequate | Probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A) |

| Inadequate | Sufficient | Strong (c)(2) (human cells or tissues) | |

| Limited | Less than Sufficient | Strong (b)(1–3) | |

| Limited or Inadequate | Not necessary | Strong (b) (mechanistic class) | |

| Limited | Less than Sufficient | Limited or Inadequate | Possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B) |

| Inadequate | Sufficient | Strong (b)(3), Limited, or Inadequate | |

| Inadequate | Less than Sufficient | Strong b(1–3) | |

| Limited | Sufficient | Strong (c) (does not operate in humans)c | |

| Inadequate | Sufficient | Strong (c) (does not operate in humans)c | Not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans (Group 3) |

| All other situations not listea bove | |||

a The evidence in bold italic represents the basis of the overall evaluation; the mechanistic subcategories refer to the schema listed above.

b Human cancer(s) with the highest evaluation.

c The strong evidence that the mechanism of carcinogenicity in experimental animals does not operate in humans must specifically be for the tumor sites supporting the classification of sufficient evidence in experimental animals.

SOURCE: IARC, 2019, Table 4. Reprinted from International Agency for Research on Cancer. Preamble: Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans (amended 2019), page 37, Copyright 2019. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Preamble-2019.pdf (accessed November 16, 2021).

a The evidence in bold italic represents the basis of the overall evaluation; the mechanistic subcategories refer to the schema listed above.

b Human cancer(s) with the highest evaluation.

c The strong evidence that the mechanism of carcinogenicity in experimental animals does not operate in humans must specifically be for the tumor sites supporting the classification of sufficient evidence in experimental animals.

SOURCE: IARC, 2019, Table 4. Reprinted from International Agency for Research on Cancer. Preamble: Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans (amended 2019), page 37, Copyright 2019. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Preamble-2019.pdf (accessed November 16, 2021).

E-CIGARETTES

The National Academies’ report Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes (NASEM, 2018) is a review commissioned by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with the goal of informing the public, FDA, and Congress about the state of scientific evidence relating e-cigarettes to public health, including short- and long-term health effects. A chapter of that report that presents a framework for, and systematic review of, the causal links between electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS; also known as “e-cigarettes”) and human health. That chapter provides the basis for the summaries here. While e-cigarettes are regulated as tobacco products by FDA, the report has no direct regulatory implications, although the results could inform FDA regulatory decision-making and federal research priorities.

The review categorized potential health effects of e-cigarettes as having one of six levels of evidence:

- Conclusive evidence

- Substantial evidence

- Moderate evidence

- Limited evidence

- Insufficient evidence

- No available evidence

Types of Evidence and Evidence Selection Process

The Statement of Task charged the National Academies’ committee with conducting a “comprehensive and systematic assessment and review of the literature on the health effects of e-cigarettes. The committee’s approach to this task was informed by published guidelines for conducting systematic reviews, as well as the approaches taken by prior National Academies committees” (NASEM, 2018, p. 43). The committee’s approach therefore incorporated major attributes of systematic reviews, augmented by initially setting out a conceptual model of the underlying causal relationships to help organize and orient the assessment. The committee systematically located (by searching PubMed,36 Scopus,37 World of Science,38 American Psychological Association PsycInfo,39 Medline,40 and Embase,41 using key words listed in the report—an appendix gives full details of the search terms), screened, and selected studies for review, using predefined criteria to select studies for inclusion and exclusion; evaluated individual studies for strengths and limitations; and synthesized findings into an assessment of the overall body of literature. The aim of the initial search was “to identify all literature on e-cigarettes” with no limits on date, language, or country; however, the committee drew on existing bodies of evidence to evaluate the known health risks of known constituents and contaminants of e-cigarettes (NASEM, 2018, p. 44). Some special searches were conducted on the results to identify literature specifically on dependence outcomes, tobacco smoking initiation, and cessation outcomes. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevance to the committee’s Statement of Task.

Assessing Individual Study Relevance and Quality