Options for a National Plan for Smart Manufacturing (2024)

Chapter: 4 The State of Smart Manufacturing Technology and Strategies to Address the Challenges

4

The State of Smart Manufacturing Technology and Strategies to Address the Challenges

A U.S. CYBER INFRASTRUCTURE TO PROPEL SMART MANUFACTURING ADOPTION

Using an important analogy to the U.S. Interstate Highway System established after World War II, one could consider establishing a national transformative data infrastructure—a concept the committee refers to as the “Cyber Interstate”—to scale data and expertise sharing as a key capability for maximum industry-wide smart manufacturing impact. Just like the U.S. Interstate Highway System, a U.S. Cyber Interstate would be an important infrastructure asset and a technical framework to enable smart manufacturing.1 The notion of the Cyber Interstate broadens recent recommendations to be more comprehensive and to inspire the standards; coordination; and new organizational structures, system integration, and workforce development that drive and accelerate maximum industry innovation and global leadership. Market share, jobs and economic sustainability, environmental sustainability, and national security at the scale of the U.S. manufacturing industry are the outcomes that could be enabled. While these are cross-agency objectives, the Department of Commerce, specifically the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), is the logical lead agency for this U.S. Cyber Interstate.

___________________

1 See Section 3.1.2 in the 2022 National Strategy for Advanced Manufacturing out of the National Science and Technology Council Subcommittee on Advanced Manufacturing and the Committee on Technology, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) 2022 report Toward Resilient Manufacturing Ecosystems Through AI, which is referenced in the National Strategy.

This Cyber Interstate vision stems from the pervasive application of manufacturing data and all modes of modeling throughout the industry that gain power and continuously learn from the industry-wide availability of the needed data and expertise. This vision also depends on an industry that values and uses data differently, invests differently, and calculates return on investment differently than it does today. This vision is also for an industry that repurposes an enormous amount of time, effort, creativity, and expense in dealing with a fragmented cyber infrastructure and reinventing common capabilities to instead focus on new higher-value products and technologies.

A Cyber Interstate would build on 50 years of the Internet and 20 years of cyber infrastructure development2 to provide the secure data highways; the on and off ramps, expectations, system integration, tools, and standards for managing and sharing data; the service stations for accessing the resources and expertise; and the rules and workflows for data and expertise sharing. Just like the Interstate Highway System was constructed over many years, but inspired and motivated significant change and co-development from the beginning, a Cyber Interstate would evolve with smart manufacturing over time; any intent to build it would inspire and provide much needed impetus in U.S. manufacturing to

- Scale workforce development;

- Scale industry adoption of smart manufacturing for business and market disruption; and

- Scale the adoption of smart manufacturing as a primary strategy for environmental, financial, and social sustainability.

Such a U.S. Cyber Interstate would provide the infrastructure for many interrelated programs. University programs have a basis to orient toward teaching how to collect and apply manufacturing data, including today’s escalating emphasis on artificial intelligence (AI). The Cyber Interstate would inspire completed templates for key data categories by sector (e.g., defense, automotive, semiconductor, food, pharmaceuticals, chemicals/materials, energy). Responsible organization(s) for maintaining data frameworks by sector could be identified. The Cyber Interstate also gives reason to establish the following:

- Static harmonized data agreements, which are like size of lane, direction of the road, and traffic signs—for smart manufacturing, one can start with basic and sharable data formats and schemas that lower the barriers for entrance.

___________________

2 University of California, Los Angeles, n.d., “Timeline: 1969: The Internet’s First Message Sent From UCLA,” https://100.ucla.edu/timeline/the-internets-first-message-sent-from-ucla, accessed October 26, 2023. Stanford University, et al., 2005, “Dedication: Birth of the Internet,” http://ana-3.lcs.mit.edu/~jnc/history/Internet_plaque.jpg.

- Dynamic standards that articulate data rules for business-oriented data interoperability requirements, trust, and security, which are like rules of the road, allowable vehicles, passing rules, merging priorities, off ramps, and on ramps—for smart manufacturing, these rules influence how data are merged and managed.

It is essential to the scaling and system integration of smart manufacturing to have data streaming formats that preserve semantics. Raw data from sensors and devices are not useful without contextualization (e.g., understanding of the nature of the data, how and when sensors were calibrated, what was measured, the equipment or process type that produced the data, the process purpose of what the equipment is doing, and the objectives for which the data will be used). The contextualized data become useful at scale when they are categorized, discoverable, and accessible for aggregation and further use in the industry. Similarly, simulation results require contextualization—for example, element type, kernel function used, boundary conditions, convergence criteria, and material model and its time-dependent and temperature-dependent property parameters. Innovative technologies, services, infrastructure, and software tools are needed to provide integration and manufacturers’ assurances that their valued data will be protected when aggregated industry-wide and used to provide the scaled, enhanced benefits of AI methods. Those benefits would include new network-based business models that provide faster process development and increased productivity, quality, and environmental sustainability.3

The Cyber Interstate must simultaneously address scaling, integration, and industry adoption for business and market disruption. New business models are needed to scale industry adoption, which could become like freeways or tollways. For smart manufacturing, new business models can be encouraged with tax incentives for developing technologies, for sharing data, or for developing the “uber ridesharing” for data. The “toll” amount can be based on metrics related to smart manufacturing. New models are also needed to scale the adoption of smart manufacturing as a primary strategy for environmental, financial, and social sustainability. For example, there could be tax incentives to use the Cyber Interstate as the data highway infrastructure for emissions reduction targets and science-based targets.

Manufacturing consortia and institutes need to be encouraged to be data-centric with advanced modeling capabilities at scale. Broadening the “Lighthouse” concept to include intercompany industry strategies can give visibility to high-performing U.S. examples of individual plants and their broader supply chain networks. This visibility can include their playbooks with data, modeling, and orchestration,

___________________

3 NIST, 2022, Towards Resilient Manufacturing Ecosystems Through Artificial Intelligence—Symposium Report, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ams/NIST.AMS.100-47.pdf.

searchable by specific manufacturing sector and enterprise size. Important examples of key performance indicators (KPIs) would include the following:

- Formalization of Lighthouse KPIs such as time to market, cost, number of product variations supported, worker engagement and enablement, decarbonization progress, and inventory efficiency.

- Growth of discoverable data categorized by manufacturing operation and function from “certified” Lighthouse factories, supply chain networks, or Manufacturing USA institutes.

- Growth of annual engagement with these Lighthouses by the broader manufacturing community.

The Cyber Interstate concept needs to be built out with data support mechanisms. Data analytics services could be like gas stations and service areas along the highway—for smart manufacturing, this implies the value of a distributed business model, while still taking advantage of common tools (e.g., U-Net for imaging processing, numerical models for process simulations). Experts are needed to handle local and individualized data (i.e., determine the most effective channel inputs to U-Net based on a specific problem, or model setup for a casting process). Existing manufacturing institutes, university research institutes, engineering consulting firms, or startups can provide such services. There also needs to be national and regional planning like urban planning for interstate and local streets—for smart manufacturing, “local” can be organized based on geographic needs or industry sector needs. Sector-to-sector or local-to-local needs can be coordinated at the national level.

In summary, fully realizing and accelerating the scaling potential of a Cyber Interstate requires the adoption of new business structures and practices that enable the industry to take advantage of being networked and interconnected. Even though the real-time collection and analysis of streaming data from the shop floors are key enablers for improving processes and monitoring the state of physical manufacturing plants, streaming data are characterized by high throughput, diversity and number of streams, heterogeneous formats and protocols, and variable spatial-temporal resolution, which impose several challenges when it comes to transforming data into actionable knowledge. In the absence of advanced, categorized, secure contextualized data hubs, manufacturers resort to the traditional download practices for in-field data acquisition, which are tedious, error-prone, and often improper for real-time data analytics. There is significant value in creating extensible and open-access data infrastructure that provides a common middleware substrate for development and deployment of domain-specific analytics on streaming data as well as reliable hosting of applications with seamless access to in-field Internet of Things (IoT) and sensing devices. Data provenance is critical to ensure

that the data analytics are meaningful. Similarly, the protection of data streams is crucial to ensure that readings are accurate and sensors are tamper-proof.

None of the above are possible without using the Cyber Interstate to scale workforce development. The manufacturing institutes, professional societies, academic institutions, coalitions, and corporations need to align and combine on education and workforce development as a key mission. In the context of the Cyber Interstate, workforce development is to prepare and train the drivers of small passenger cars or large trucks to use the highway—for smart manufacturing, the workforce needs to operate at many different levels to generate, consume, and analyze data with confidence.

The Cyber Interstate could be a government-driven investment to stimulate significant business and technical change. Surprisingly, data are still not discussed as directly as needed. The view of data as valuable, primary, and monetizable resources has grown in recent years; however, it continues to lag relative to the physical-side value of the equipment operations. Access to enough of the right data continues to be taken for granted. The industry is integrating infrastructure, not data; increasing its complexity; and fragmenting itself between the large companies that have the wherewithal to work with data and the many small and medium companies that do not. This lack of data integration is to the disadvantage of everyone.

In Chapter 1, there were findings about data, access to data, compartmentalization, and the need for an educated workforce. The findings in chapter 1 and the discussions in this chapter convinced the committee to draw the following conclusions and to make the key recommendation below:

Conclusion: The U.S. smart manufacturing sector lacks a technical infrastructure or common mechanisms to cultivate, securely exchange, and assist manufacturing companies with securing data, deploying real-time analytics, and sharing best practices across the industry. The lack of curated data hampers development of the industry and limits the capacity of new and existing companies, especially small and medium manufacturers (SMMs), to adopt and benefit from smart manufacturing technologies. Bold thinking is needed for the U.S. technical infrastructure.

Conclusion: A secure digital smart manufacturing data interstate infrastructure that serves as a conduit to connect the wider smart manufacturing community, to include existing digital connections, is critical to ensuring that data and experience are shared across the smart manufacturing industry at sufficient scales to ensure U.S. global competitiveness in a sustainable way.

Conclusion: Fully realizing and accelerating the scaling potential of the Cyber Interstate requires the adoption of new business structures and cybersecurity

practices that enable the industry to take advantage of being networked and interconnected while mitigating the cyber risks.

Conclusion: There is significant value in creating an extensible and open-access data infrastructure that provides a common middleware substrate for development and deployment of domain-specific analytics on streaming data as well as reliable hosting of applications with seamless access to in-field IoT and sensing devices.

Key Recommendation: A national plan for smart manufacturing should urgently support the establishment of national transformative data infrastructure, tools, and mechanisms to assist with (1) cultivating, selectively sharing, and securing the use of data in real time and at scale; and (2) sharing best practices to promote industry-wide technical data standards. Such infrastructure, developed as a national capability, could take the form of a secure digital network that facilitates the flow of data with controlled and credentialed access, such as a Cyber Interstate. It should be planned and coordinated with companies, government agencies, associations and consortia, and academic stakeholders.

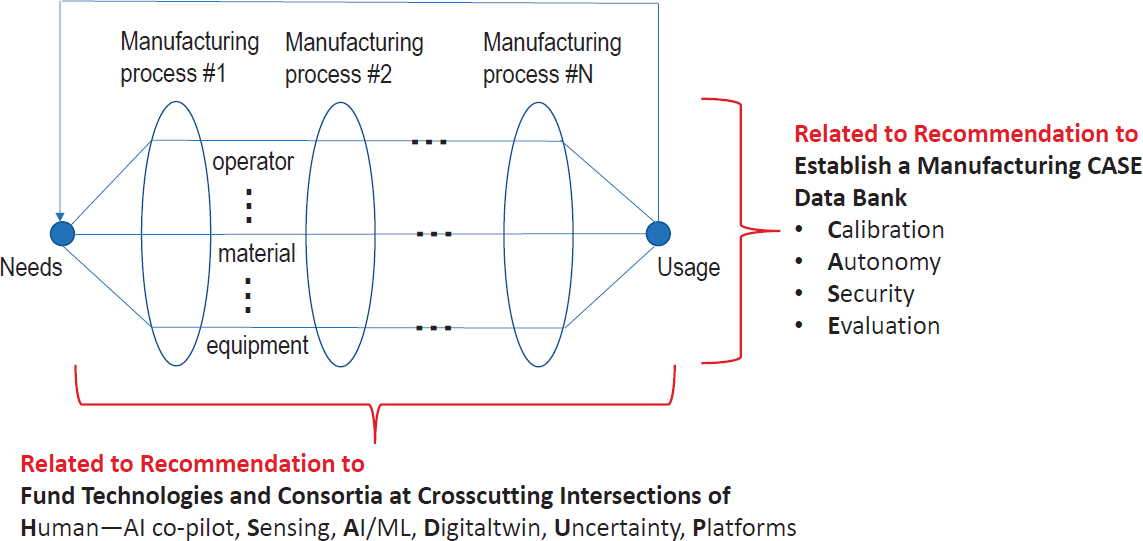

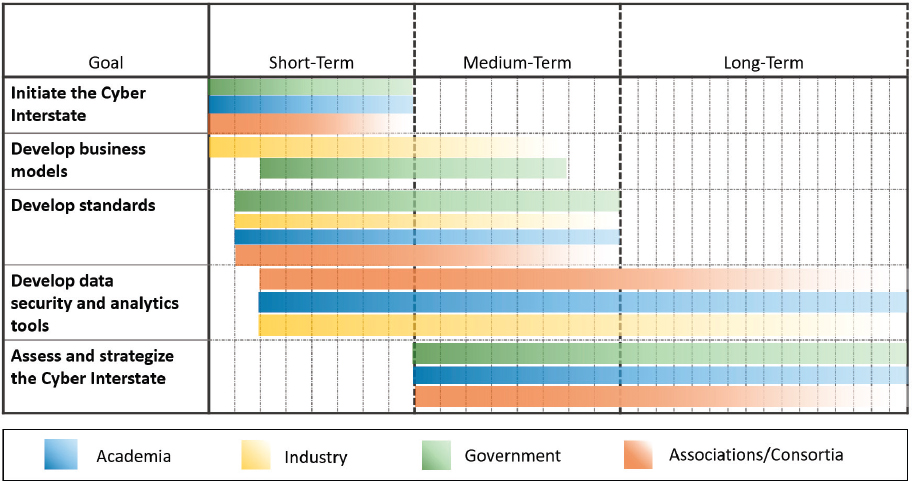

See Figure 4-1 for a timeline of the Cyber Interstate. The committee considers the short-, medium-, and longer-term timeframes to be in the ballpark of 2, 4, and 6 years, respectively.

SYSTEM AND DATA INTEGRATION FOR SMART MANUFACTURING

There is great value to enhancing and enabling digital integration within manufacturers and across supply chains. The large public models are desired to be securely combined with private data from companies and individuals. Digital integration across the value stream, including data flows to and from suppliers and data at the usage stage that flow back to the designer, drives end-to-end efficiency, productivity, precision, and stability within product production. Today, taking full advantage of generative AI is mostly done in the cloud versus on the edge, which puts pressure on manufacturing systems to connect proprietary edge systems securely to the cloud. It is important to leverage the lead that the United States has today in AI to impact the future of manufacturing—and overcome organizational, cultural, and technical barriers that face U.S. manufacturing—and to compete with other countries who are fully embracing AI and automation for the advancement of manufacturing.

DATA ISSUES RELATED TO SMART MANUFACTURING

The following sections illustrate the beneficial impacts of data sharing and, at the same time, the business and technical challenges associated with data sharing for smart manufacturing.

Benefits of Data Sharing in Smart Manufacturing

Share Data to Build and Analyze Algorithms and Models for Individual Factory or Company Use

There are many operations that are common enough that sharing data can avoid the huge resource and cost of reinventing algorithms for commonly used applications that have already been worked out. Sharing data to cut this cost goes hand in hand with sharing enough know-how about the data and the operation together to be useful. Availability of more openly shared data is key to tapping into expertise (e.g., at universities) to build better algorithms.

Share Data, Know-How, and Validation Information at Network Scale So These Can Be Discovered and Utilized as Resources via a Network Search

Change the compartmentalized way engineering and application of algorithms are done today and enable low-cost scaling to lower the cost of development and application for all.

Share Data to Improve Line, Interfactory, and Intercompany Operations

This is peer-to-peer data sharing within and across companies for productivity and precision through interoperability. This includes supply chain interoperability and also data shared in products-as-services models (e.g., pumps, filters, jet engines, printers, elevators, and sterilization services).

Share Data for Supply Chain Resilience (e.g., materials, orders, and capacities), Allowing Manufacturers in Supply Chains the Visibility of Each Other’s Capacities to Better Manage Variations and Disruptions (i.e., pandemic)

This includes sharing data for product-oriented supply chains, like consumer products that benefit from Amazon, Walmart, or Amazon-like next-day, at-your-doorstep services.

Share Data for Measuring, Sharing, and Driving Industry Sustainability Behaviors (e.g., carbon footprint monitoring)

This is data sharing about outcomes and how to measure them. These are realistic data for life-cycle analysis to assess the benefits of smart manufacturing.

Business and Technical Challenges of Data Sharing in Smart Manufacturing

Business Challenges

The internal technical and scientific data are not meant to be shared with other original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) or other SMM competitors as they are considered company proprietary and are intended to provide a company competitive advantage. New technologies are emerging to mitigate the concern of proprietary information and facilitate secure data sharing. For example, for the work on generative AI at Microsoft, almost all companies have proprietary data (not shared) and combine them in their own cloud subscription with public data (which may be a massive model, like the OpenAI models). This is secure and used for a number of scenarios like government or other manufacturing scenarios with companies today.

A company runs generative AI in its own cloud subscription and sets its own privacy policy—typically, the data in the subscription are not shared, but the company combines them with the large generative models. Modern software can adopt privacy and security from other AI scenarios that combine public and private data. Typically, Microsoft recommends that companies do not intermingle their own data in the large language model for now, so it is easy to have a strong privacy boundary.

Privacy is quite a hot topic for the generative models. Most people are using Retrieval-Augmented Generative Question and Answer (RAG-QA), which is a way to answer questions that combines two different methods. One method is called retrieval-based, which means it looks for answers in a database of information. The other method is called generative, which means it creates new answers based on what it has learned before. The RAG-QA model is a computer program that uses these two methods to answer questions. It has two parts: one part that reads the question and another part that creates the answer. To use RAG-QA with large generative models, four steps need to be followed: prepare the data, train the retriever, train the generator, and fine-tune the RAG-QA model.4 Given concerns about protection of proprietary information and competitiveness, a corporation will more likely share its capacity data with its customers rather than across or even down the supply chain.

Technical Challenges

The technical challenges are related to what characterizes “big data,” which arises from the rapidly increasing volume, velocity, and variety of data as well as the low veracity (i.e., high uncertainty) of data collected in manufacturing operations. The committee describes types of data and features of data sets in manufacturing first, followed by the handling and the post-processing of data (or curing of data).

Types of Data and Features of Data Sets (Volume, Velocity, and Variety of Data)

Different types of data are commonly seen for data-driven analysis and operation in smart manufacturing. These are summarized below with their characteristic features to establish the basis for data-related recommendations:

- Equipment builder data: Machine makers (e.g., additive manufacturing machines, computer numerical control machines) and process operation

___________________

4 O. Khattab, C. Potts, and M. Zaharia, 2021, “Building Scalable, Explainable, and Adaptive NLP Models with Retrieval,” Stanford AI Lab Blog, October 5, https://ai.stanford.edu/blog/retrieval-based-NLP.

- suppliers currently develop their own application programming interfaces to pull data, if at all. Furthermore, a mix of industry standards (Open Platform Communications–Unified Architecture [OPC-UA], MT Connect) exists in which data are in a prescribed format without a common set of standards. Often standards are not adopted with the effect that data are generally not formatted the same.

- Process data: This category can include temperature, location, pressure, gas level, and chemical content data. The lack of interoperability of sensor data between portions of the value stream or suppliers is an impediment to digital integration. To that end, IoT systems should be designed to support data interoperability as well as commonality in taxonomies, naming, and metadata attributes. Integration of data from sensors across devices and users could be possible with the creation of standards and best practices.

- Mechanical testing data: Testing methods currently follow specific test method standards (e.g., American Society for Testing and Materials, International Organization for Standardization); however, the output format can range from a pdf file to an xls file formatted to the liking of the testing house, rendering the ability to access and ingest for analysis time-consuming due to manual reformatting.

- Supply chain procurement, order, and production capacity data: These relate to data flows between specific OEMs and their suppliers. There is currently a procurement data gap in not knowing where the data are or whether they are trustworthy. Data practices are dependent on bespoke supplier portals and manual updates, which creates inefficiencies in operations.

- Internal scientific or technical data: These may be found in physics-based, data-driven, or hybrid physics/data-driven models based on the extracted machine data that are pulled from machines, sensors, and mechanical testing or compiled from tacit knowledge accumulated inside a company. Every company produces valuable operational data that are embedded with its expertise. SMMs collectively have a huge amount of expertise and data on a full range of useful operations, materials, parts, quality, etc. Similarly, OEM scientific and technical data are generated for the purpose of optimizing the production workflow, with the intent of driving stability, productivity, and quality.

- Inter- and intra-organization data flows: These are data flows between equipment, line operations, factories, OEMs, SMMs, academia, government laboratories, standards organizations, and others. Because of the proprietary nature of operations and data handling, this data-sharing activity is anticipated to be limited in nature and include willing participants in existing and new consortia, with the aim of creating and validating models that improve the efficiency of manufacturing production.

Conclusion: There is a critical need for standards to facilitate data sharing across the smart manufacturing industry. Currently a “mix” of industry standards exists, with different organizations adopting different models, which hampers sharing and curation.

Veracity of Data

In many cases, the calibration process is not presented with the measured or simulated data, which leads to uncertainty in understanding the ground truth of the data. How and when was the machine or instrument or simulation model that produced or used the data calibrated? There are gaps in machine and process calibration standards that need to be addressed to provide confidence in data (e.g., additive manufacturing, computed tomography scanning and other nondestructive inspection). The environmental effects (such as humidity and temperature) introduce further variability. Any lack of such data recording or calibration procedure leads to uncertainties in the data collection process, which in turn are propagated into the resulting data set. This presents challenges in adequately quantifying and managing these uncertainties and ensuring data quality as the material basis for informed decision-making.

Data Curation

Data curation plays a crucial role in the active and continued management of data throughout their life cycle. The process enables data retrieval and access, ensures data quality, and adds value.5 Current general practices in data curation involve data organization and retrieval, such as naming files, structuring folder directories, and creating metadata to describe the data in a standardized way. A key understanding is that most factories (especially SMMs) do not have enough of the right data harmonized. As a result, much time is wasted by reformatting technical data between vendors.6,7,8 Additionally, data quality assurance provides techniques to enable data cleansing, data balancing, and data annotation, facilitating downstream data-driven tasks and decision-making.

___________________

5 M.H. Cragin, P.B. Heidorn, C.L. Palmer, and L.C. Smith, 2007, “An Educational Program on Data Curation,” https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/3691.

6 A. Ruiz, 2017, “The Cognitive Coder: The 80/20 Data Science Dilemma,” InfoWorld, September 26, https://www.infoworld.com/article/3228245/the-80-20-data-science-dilemma.html.

7 J. Snyder, 2019, “Data Cleansing: An Omission from Data Analytics Coursework,” Information Systems Education Journal 17(6):22–29.

8 M. Sing, 2021, “Simplify and Democratize Your Data with Less Hassle and Cost,” IBM (blog), June 24, https://ibm.com/blog/announcement/simplify-and-democratize-your-data-with-less-hassle-and-cost.

Data Security and Overall Cybersecurity

A survey showed that 91 percent of manufacturers are invested in digital technologies, but 35 percent say that the accompanying cybersecurity challenges and vulnerabilities inhibit the manufacturers from doing so fully.9 Nevertheless, SMMs—the backbone of the U.S. manufacturing industry—typically have limited cybersecurity skills and resources, which prevents them from taking advantage of the smart manufacturing technologies that drive information sharing and materials exchange across digitally controlled supply chain networks.10

The digital thread is about how to connect engineering designs and interconnected manufacturing operations—and this thread must be secure. One of the key elements of that security is the proprietary information and critical data that companies—and their adversaries—value. Securing these operations is necessary at the final assembly stage but also throughout all tiers of the supply chain (Tier 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and so on).11

Securing these digital threads requires new cyber-informed, secure-by-design architectures to be placed into or onto legacy and new systems and develop future-state, secure manufacturing architectures that are secure by design and informed by deep knowledge of the evolving threat vectors. These architectures enable manufacturers to maximize security, resiliency, and overall market competitiveness in the face of current and evolving threat vectors.12

An approach to cyber-physical security would benefit from an open reference architecture in which systems are intrinsically secure. The side effect of next-generation security is the extinction of entire categories of vulnerabilities. For existing systems, there is a need for new concepts that drive toward high levels of security, achievable within the current constraints.

Cybersecurity solutions should include formal verification, continuous integration/continuous delivery, digital twin, secure gateways, trust-but-verify components, cyber-physical passport, and the global supply chain ledger. Next-generation secure smart manufacturing architectures and protocols should incorporate AI-enabled threat detection and response mechanisms to detect and respond to cyberattacks in real time. AI-enabled threat detection uses machine learning (ML) algorithms to analyze network traffic, detect anomalies, and identify potential threats. Furthermore, using cryptographic solutions, intrusion identification, and ledgers can help protect against cyberattacks that target interconnected devices and systems. Secure communication protocols ensure that data transmitted

___________________

9 CyManII, 2022, Cybersecurity Manufacturing Roadmap, https://www.readkong.com/page/cybersecurity-manufacturing-roadmap-2022-public-version-4777079.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

between devices and systems are encrypted and cannot be intercepted or modified by unauthorized parties.

Conclusion: An approach to cyber-physical security should be an open reference manufacturing architecture in which systems are intrinsically secure.

Key Recommendation: The Department of Energy in partnership with the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the Department of Defense, and manufacturing institutes should establish manufacturing CASE (Calibration, Autonomy, Security, Evaluation) Data Banks (CASE-DB) with the next generation of secure manufacturing architectures.

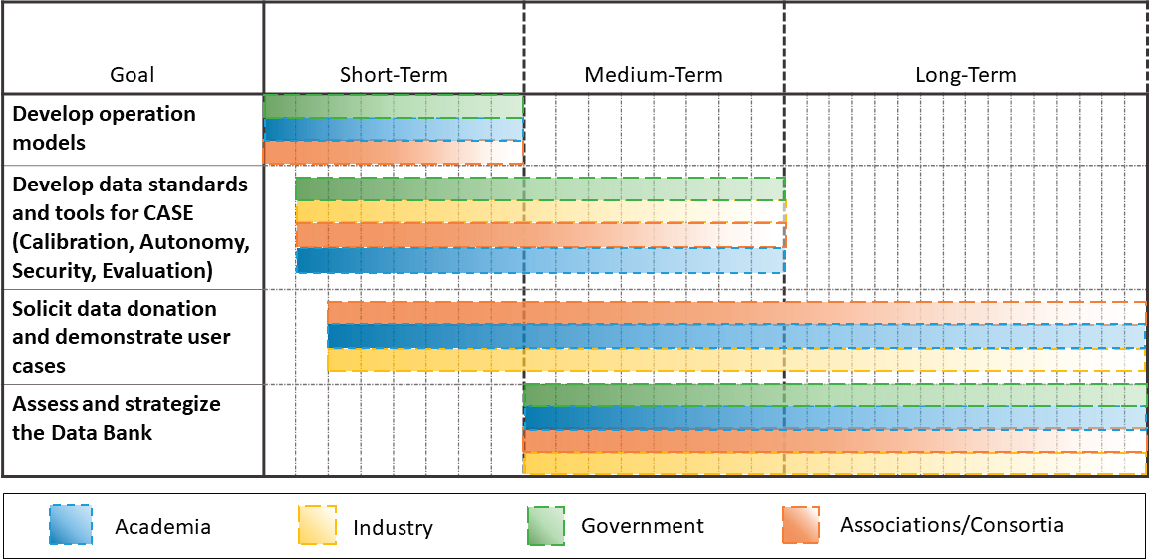

To realize the above-mentioned benefits and to address the business and technical challenges of data sharing, the committee envisions data banks with data contributed or donated by sources in the manufacturing community that are rigorously validated to realize multifaceted functions as described below. See Figure 4-2 for a timeline. The committee considers the short-, medium-, and longer-term timeframes to be in the ballpark of 2, 4, and 6 years, respectively.

Functions Enabled by Data Banks

Share the State of the Art of Calibration Techniques and Enable the Implementation of the Proper Calibration Technologies Using the Benchmark Data in the CASE-DB

The goal is to ensure data transparency and validity as the basis for informed, robust decision-making. It will be necessary to require equipment and machine tool builders to adopt minimum viable OPC-UA for specific machine categories and adopt calibration standards. The CASE-DB will also provide benchmark data for software developers to develop a robust calibration process.

Assess the Autonomy Level and Provide an Autonomy Index of Software and Sensors Submitted for Evaluation Using Data in the CASE-DB

Autonomy refers to the level of automation between data collection and models. The goal is to provide an autonomy index to products of solution providers. Using standards will help increase the autonomy level. Use of common data models to build pre-engineered solutions for high-value applications in key industries, such as electric vehicle production, battery assembly, food and consumer goods packaging, batch processing, and energy management, will accelerate the adoption of smart manufacturing by SMMs. The autonomy index will provide SMMs with a clear index such that they can effectively select the tools (software or hardware) to meet their smart manufacturing goals based on their technical competence within the company.

Provide Guidelines for Cybersecurity

A framework to detect vulnerabilities and include risk mitigation is recommended. Cyber threats can include attacks on supply chain partners, such as vendors or subcontractors, which can lead to data breaches or sabotage of critical systems. A modular and extensible methodology that can be applied to existing or new manufacturing facilities and supply chains to estimate energy savings and emissions reduction while maintaining a desirable level of cyber resiliency is desirable, which will help with creating consistent baselines for cybersecurity. The baselining step also incorporates knowledge of cyberattacks or breaches, when available, and consequence-based risk analysis to assess overall risk and compute cybersecurity return on investment.

Evaluate the Compatibility of Data Packages with Known Data Schema and Industrial Standards

The CASE-DB can be used for reinforcing the standardized format of output from existing or new methods; for creating a viable set of interoperable data and metadata formats (e.g., sensor ID/name, observation/reading, engineering units, time of acquisition, location, accompanying metadata) that work across devices and domains, augmented with naming and taxonomy systems; for creating and standardizing a common supplier procurement interface that can integrate with any enterprise resource planning system, with the ability to syndicate the information with other platforms; and for providing the ability to update data across many platforms simultaneously.13

ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY NEEDS FOR SMART MANUFACTURING

Technology needs for smart manufacturing cover nearly all disciplines of science, engineering, and social sciences. With the assumption that individual technologies have been developed through existing and regular funding channels, the committee focuses on six interdisciplinary technologies that are highly demanded by the smart manufacturing community—that is, human–AI co-piloting, sensing, AI/ML, operational technology/information technology (OT/IT) integration through platforms, digital twins, and uncertainty quantification. These technologies further define the basic technology elements for realizing smart manufacturing originally called out by the Department of Energy (DOE) as advanced sensing, controls, platform, and modeling.

Six Key Technologies in Smart Manufacturing

Human–Artificial Intelligence Co-Piloting

There has been some debate over the role of humans in tomorrow’s factories that deploy smart manufacturing technologies. Robotics and automation are important components of smart manufacturing technology. As these technologies are increasingly deployed in factories, the need for humans to perform tedious and repetitive work is considerably reduced. Unfortunately, terms such as “lights-out factories” in the context of smart manufacturing have caused concerns that humans might not have any role in tomorrow’s factories that deploy smart manufacturing technologies.14

___________________

13 M. Milenkovic, Intel Corporation, Internet of Things Group, n.d., “Towards a Case for Interoperable Sensor Data and Meta-Data Formats, Naming and Taxonomy/Ontology,” https://www.w3.org/2014/02/wot/papers/milenkovic.pdf, accessed October 3, 2023.

14 C.J. Turner, R. Ma, J. Chen, and J. Oyekan, 2021, “Human in the Loop: Industry 4.0 Technologies and Scenarios for Worker Mediation of Automated Manufacturing,” IEEE Access 9:103950–103966.

Conclusion: Human–AI co-piloting is needed as a foundational premise in the drive for smart manufacturing, which is the central theme of Industry 5.0.

With human–AI co-piloting, the primary strengths in humans and machines together include the following.

Cognition (Human)

Smart machines are unlikely to surpass the significant strengths possessed by humans anytime soon. While smart machines excel at data processing, analysis, and pattern recognition, humans possess superior high-level cognitive abilities such as problem-solving, critical thinking, and decision-making. Humans also exhibit dexterity, flexibility, and adaptability, which are traits not yet achieved by the current generation of robots and controls. Furthermore, humans can think creatively and generate new solutions in challenging situations. By leveraging human strengths and providing people with additional training for new AI-enabled skills, smart manufacturing can achieve efficient, effective, and resilient factories of the future.15

Decision-Making (Human)

Humans play an important role in smart manufacturing. These roles range from strategic decision-making to day-to-day supervision or oversight of the process. To ensure smooth operations of the production process, humans are needed to provide expertise and decision-making skills. Their contribution includes tasks such as monitoring and adjusting production parameters, identifying and addressing equipment malfunctions, and troubleshooting production issues. Additionally, humans are crucial in ensuring ethical, safe, and sustainable smart manufacturing practices. This human analysis involves identifying and mitigating potential risks related to the deployment of new technologies and ensuring that production processes are environmentally sound and socially responsible.

The need for humans to make decisions associated with the deployment of smart manufacturing technologies will remain: the design, programming, and maintenance of rapidly evolving advanced technologies used in smart manufacturing cannot be accomplished without significant human involvement. In the

___________________

15 J. Jiao, F. Zhou, N.Z. Gebraeel, and V. Duffy, 2020, “Towards Augmenting Cyber-Physical-Human Collaborative Cognition for Human-Automation Interaction in Complex Manufacturing and Operational Environments,” International Journal of Production Research 58(16):5089–5111.

factories of the future, humans will play a pivotal role in decision-making, utilizing their expertise and judgment to deploy, upgrade, and retire technologies.16

Control (Human) and Collaboration (Machine)

Human-in-the-loop and human–robot collaboration are needed to handle processes that are difficult to automate or that still need to build confidence and trust with data and modeling in building toward automation and autonomy. Currently, humans are responsible for 72 percent of manufacturing tasks on the factory floor. Not all steps of manufacturing can be automated in a cost-competitive manner. As a result, many tasks in the future will still necessitate human control or involvement. By leveraging the complementary strengths of humans, robots, and various kinds of control and management systems, work environments can become more efficient, effective, and productive. To optimize production processes, humans will need to collaborate with machines, and continue to identify areas for improvement and enhance efficiency. Given that AI will increasingly enable “co-piloting” by both managers and frontline workers, we must ensure that AI privacy and security policies designed for smart manufacturing can evolve as the technology and workforce evolve, and continue to identify areas for improvement and enhance efficiency, privacy, and security.17,18

Quality Assurance and Customization (Human)

Humans are needed to provide quality assurance: the definition of quality control criteria requires human input. Humans will continue to play a critical role in monitoring production processes and ensuring that products meet quality standards.

Humans are needed for realization of customized products: most industry sectors are facing pressure to manufacture customized products in a cost-effective manner. Designing and producing unique and personalized products for consumers requires human involvement. With the help of advanced automation, manufacturers can integrate more customization and adapt to small changes in their

___________________

16 X. Xu, Y. Lu, B. Vogel-Heuser, and L. Wang, 2021, “Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, Conception and Perception,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems 61:530–535.

17 D. Mukherjee, K. Gupta, L.H. Chang, and H. Najjaran, 2022, “A Survey of Robot Learning Strategies for Human-Robot Collaboration in Industrial Settings,” Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 73:102231.

18 H. Ravichandar, A.S. Polydoros, S. Chernova, and A. Billard, 2020, “Recent Advances in Robot Learning from Demonstration,” Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems 3:297–330.

processes, making it possible to produce tailored products.19 Human-supervised smart automation can extend this capability to a larger scale.

Quality assurance and customization, particularly for new, complex, and ambiguous tasks, are areas where humans can provide improved manufacturing contributions. Over time, as some of these tasks become common, AI can increasingly be used to validate and complete additional scenarios.

Sensing

Sensors provide the physical infrastructure for data or information acquisition throughout smart manufacturing—from unit to cross-enterprise manufacturing and the entire life cycle of a product—and provide the essential knowledge base for the CASE-DB. Thanks to the improvements of the industrial IoT and high-granular data acquisition technologies, baseline models can be constructed in a reliable and efficient way using wide-ranging data types spanning large frequency ranges from manufacturing systems.20,21 For instance, the implementation of smart sensors in a shop floor can generate data relevant to safety, productivity, quality, energy consumption, and emission baselines.22

Accessibility of Sensors to Source of Information

Sensor housing design directly affects sensor accessibility to the source of signal generation and plays a critical role in high-quality data collection and information acquisition that forms the foundation for smart manufacturing, to detect and trigger automated and manual workflows. General practice in sensor design focuses on economical mass production of sensors. While cost-effective, generic geometrical designs such as cylinders or cubes, as commonly adopted, limit the options for sensor placement. The result is suboptimal fitting of sensors to the manufacturing applications of interest in that the sensors may not be able to be placed in close

___________________

19 Y. Qi, Z. Mao, M. Zhang, and H. Guo, 2020, “Manufacturing Practices and Servitization: The Role of Mass Customization and Product Innovation Capabilities,” International Journal of Production Economics 228:107747.

20 T. Kalsoom, N. Ramzan, S. Ahmed, and M. Ur-Rehman, 2020, “Advances in Sensor Technologies in the Era of Smart Factory and Industry 4.0,” Sensors 20(23):6783.

21 S. Abbasian Dehkordi, K. Farajzadeh, J. Rezazadeh, R. Farahbakhsh, K. Sandrasegaran, and M. Abbasian Dehkordi, 2020, “A Survey on Data Aggregation Techniques in IoT Sensor Networks,” Wireless Networks 26:1243–1263.

22 V.J. Mawson and B.R. Hughes, 2019, “The Development of Modelling Tools to Improve Energy Efficiency in Manufacturing Processes and Systems,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems 51:95–105.

proximity to signal generation, leading to potentially contaminated, low signal-to-noise ratios in the collected data.23

Additive manufacturing opens up new opportunities for customizing sensor housing design (instead of “one-size-fits-all”) and fabrication for tailored, optimal data acquisition in order to meet a great variety of manufacturing process sensing requirements.24 These requirements, depending on the application, can include chemical and material compatibility and sterility.25 This approach complements the need for mass production of sensors to economically realize data democratization while addressing application-specific scenarios where high-accuracy, high-precision data acquisition is needed. Ultimately, both approaches contribute to meeting the requirements for smart manufacturing.

Co-Design of Sensing and Data Analytics

Sensor development has generally been pursued independently from data analytics in the data processing downstream or in process or product design upstream even though considerable efforts have been made by commercial software firms to perform multidisciplinary multi-objective design. With increasing complexity of data analytics, especially using AI algorithms, decoupling of data collection and data analytics can lead to suboptimal information extraction and increased bandwidth requirements and communication latency. Co-design of sensing and data analytics functions through concerted hardware-software integration has the benefit of streamlined information processing and transmission with reduced bandwidth requirement and latency, and ultimately benefits a more optimized design of manufacturing process and product.26,27 Additionally, co-design ensures observability for function; strengthens needed engineering for conditional actions, such as addressing missing data and sensor errors; and providing predictable degradation to unrecognized events. Furthermore, incorporating sensor–controller co-development as a topic into funding programs promotes interdisciplinary

___________________

23 J. Cao, E. Brinksmeier, M. Fu, et al., 2019, “Manufacturing of Advanced Smart Tooling for Metal Forming,” CIRP Annals 68(2):605–628.

24 M.S. Hossain, J.A. Gonzalez, R.M. Hernandez, et al., 2016, “Fabrication of Smart Parts Using Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Technology,” Additive Manufacturing 10:58–66.

25 X. Ruan, Y. Wang, N. Cheng, et al., 2020, “Emerging Applications of Additive Manufacturing in Biosensors and Bioanalytical Devices,” Advanced Materials Technologies 5(7):2000171.

26 M. Nakanoya, S.S. Narasimhan, S. Bhat, et al., 2023, “Co-Design of Communication and Machine Inference for Cloud Robotics,” Autonomous Robots 47(5):1–16.

27 Y. Ma, T. Zheng, Y. Cao, S. Vrudhula, and J.S. Seo, 2018, “Algorithm-Hardware Co-Design of Single Shot Detector for Fast Object Detection on FPGAs,” In 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD), https://doi.org/10.1145/3240765.3240775.

collaboration across these traditionally separate fields of research and development and enables continued innovation.

As sensor data are increasingly used to automate workflows, it will be critical to ensure that the data collected and work processes triggered by sensors are secure and that there are clear processes for actions that require human approval and override.

Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning

AI in manufacturing refers to software systems that can recognize, assess, simulate, predict, and optimize situations, operating conditions, and material properties for human and machine action. As trust and confidence build, data-centered modeling and AI applications mature and progress through dashboards, human-in-the-loop, operations control, automated, and autonomous operations. ML, which is a subset of AI, refers to algorithms that use prior data to accurately identify current state and predict future state, with the goal of improving productivity, precision, and performance. Smart manufacturing and AI have evolved together over 50 years such that today they are an integrated concept. The importance of data is further exemplified when powerful AI methods are applied for expanding knowledge, increasing prosperity, and enriching the human experience. The full potential of AI accrues from orchestrated industry-wide actions that encourage adoption. In short, smart manufacturing defines industry digitalization for scaling AI.28

It is important to create shared data that can be used for smart manufacturing (such as large language models or other domain-specific public data) and that organizations have clear ways to securely and confidentially aggregate selected data for public use as well as combine their proprietary data with public data to improve model accuracy and robustness, without “leaking” confidential information (e.g., searches, usage, documents) to the public. Additionally, these large AI features should be able to work offline as well as in the cloud, given the need for factories to work in areas where there is no cloud access or data must be housed on premises. This is a new area with much innovation, and smart manufacturing should build on the innovation, privacy, and security and be flexible as AI systems evolve and improve over time. Edge-cloud infrastructure and platform technologies are critical to enabling and scaling data sharing and data interoperability for robust local and collaborative model development, data exchange for operation interoperability, and logistics visibility for more resilient supply chains.

___________________

28 NIST, 2022, Towards Resilient Manufacturing Ecosystems Through Artificial Intelligence—Symposium Report, https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ams/NIST.AMS.100-47.pdf.

Integrating AI/ML with physical domain knowledge is crucial to realizing smart manufacturing.29 While AI/ML methods have demonstrated their ability in capturing complex nonlinearities and dynamics underlying manufacturing processes, thus effectively representing an enabling tool for manufacturing process modeling and optimization, a limiting factor is their reliance on sufficient training data sets. This leads to difficulty in the AI/ML model generalizability beyond the range of training samples as well as to potential spurious discoveries that are inconsistent with physical laws.30 Causality and inference remain particularly important AI considerations in manufacturing that are not addressed adequately with ML. These issues hamper the trustworthiness of AI/ML models and their broad acceptance, especially for decision-making in critical applications.31,32

On the other hand, physics-based models are not necessarily more affordable, faster, or scalable for operational use or for producing data. The ability to manage and securely share data to produce the data sets is of equal importance in manufacturing’s modeling arsenal. As noted, manufacturing needs the complementary advantages and increased understanding that come with both physics-based models and direct data-centered models and the ability to use them together.

The industry has not sufficiently embraced the intrinsic value and embedded knowledge in operational data. The current business culture of trade secret protection is an acknowledged barrier to viable and affordable AI applications. More subtle is an engineering culture in which the value of data as primary and monetizable resources continues to lag. Access to enough of the right data continues to be taken for granted when, in reality, this is not the case for most manufacturers. Lastly, the continuing legacy of software applications still in service in which the data are embedded and therefore trapped in the function needs to be acknowledged and addressed.

Developing the infrastructure, platforms, and tools for integrating AI/ML with public data is therefore critical. This includes large AI models for general knowledge and physical domain knowledge, as well as private propriety data, without intermingling private data. This also enables the creation of scaled “hybrid models”

___________________

29 Y. Du, T. Mukherjee, and T. DebRoy, 2021, “Physics-Informed Machine Learning and Mechanistic Modeling of Additive Manufacturing to Reduce Defects,” Applied Materials Today 24:101123.

30 Y. Xu, S. Kohtz, J. Boakye, P. Gardoni, and P. Wang, 2022, “Physics-Informed Machine Learning for Reliability and Systems Safety Applications: State of the Art and Challenges,” Reliability Engineering & System Safety 230:108900.

31 M. Mozaffar, S.H. Liao, X.Y. Xie, et al., 2022, “Mechanistic Artificial Intelligence (Mechanistic-AI) for Modeling, Design, and Control of Advanced Manufacturing Processes: Current State and Perspectives,” Journal of Materials Processing Technology 302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2021.117485.

32 S. Guo, M. Agarwal, C. Cooper, et al., 2022, “Machine Learning for Metal Additive Manufacturing: Towards a Physics-informed Data-Driven Paradigm,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems 62:145–163.

for local deployment, that combine the complementary strengths. Specifically, the robustness of physics-based models ensures consistency with the first principles and generalizability of the models’ outcome, whereas the flexibility of data-driven models is maintained to ensure model adaptivity to process dynamics.33 Physics-based constraints can be added as a soft constraint represented in the cost/penalty/loss function or as a hard constraint represented in the network architecture. Such integration alleviates the limitations of pure data-driven AI/ML models and efficiently leverages data collected during manufacturing processes to effectively address complexities in real-world manufacturing. As AI/ML is being increasingly recognized as one of the fundamental skills for engineers in the era of digital and smart manufacturing, a trend of incorporating AI/ML materials into the curriculum and thesis work has been clearly seen in many institutions in recent years.

Platforms That Integrate Operational Technology with Information Technology

Bridging the gap between OT and IT represents a significant leap with smart manufacturing. The convergence of technologies in the two domains can unlock several benefits through the incorporation of IoT, cloud computing, edge computing, etc., with advanced data analytics enabled by AI/ML. Specifically, IoT offers a new level of observability into operations by enabling real-time data collection from multiple points throughout the manufacturing process. Platform technologies offer the ability to manage data contextualization through multiple IT and OT layers, freeing data for multiple applications.

Platform technology abstracts the data from their function so that data can be used consistently for multiple functions involving multiple AI/ML and physics-based models that are orchestrated together. Platform technologies make it possible to readily add sensors to enrich an application or change applications while ensuring consistent contextualized data. Finally, platform technologies open the door for categorizing, discovering, sharing, and aggregating contextualized data and applications as apps that can be orchestrated. From an operational standpoint, data can be processed at scale and stored with cloud technology for broad-based access. Many uses stem from this. Decision-making for higher productivity and more robust quality control across similar machines or processes in different line operations is enabled. Also, it becomes possible to manage distributed operations together, supporting products as service models and intra- and intercompany line operation interoperability. Local infrastructure requirements are lowered for many manufacturers, and security is better and more consistent.

___________________

33 S. Ghungrad, M. Faegh, B. Gould, S.J. Wolff, and A. Haghighi, 2023, “Architecture-Driven Physics-Informed Deep Learning for Temperature Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing with Limited Data,” Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering 145(8):081007.

Moreover, integrating OT with IT allows for improved supply chain management, as shared data across suppliers and customers can be better aggregated for optimized inventory management, reduced lead times, and increased responsiveness to market changes. Furthermore, the convergence of OT and IT can enhance communication and collaboration across different units within the organization, promoting a culture of continuous improvement. By allowing data processing closely to the equipment that represents the source of data generation, edge computing adds another layer of benefits in terms of reduced latency and real-time decision-making, thereby increasing the overall system reliability. By leveraging these IT techniques, OT is scaled in multiple ways to realize improved operational efficiency, enterprise competitiveness, and adaptivity to rapidly changing market demands.34

Digital Twin

Development of a digital twin involves the creation of a digital representation of a physical object or system of sufficient fidelity for it to be useful for life-cycle analysis. Real-time sensing data for digital twin updates and feedback communications with the physical object are used to update the digital twin and sustain its performance while optimizing the control of the physical object or system. Common practice in digital twin application starts with building an initial physics-based model of high fidelity to fully represent the physical object or system, and then creating a surrogate model with reduced complexity to facilitate real-time execution and control of the physical object or system. Sensing data are used to update the digital twin to close the physical-to-digital gap.35

One challenge in digital twin development is the creation of computationally efficient surrogate models that retain physical consistency with their high-fidelity counterparts. Furthermore, once a product enters its life cycle and is subject to dynamical conditions and environmental effects, the original digital twin may no longer truthfully represent the physical twin. To address these challenges, systematic research is required to effectively integrate physical domain knowledge with ML to ensure consistency between the digital replica and the physical counterpart to satisfy the requirements for real-time model execution, while having uncertainty

___________________

34 D. Berardi, F. Callegati, A. Giovine, A. Melis, M. Prandini, and L. Rinieri, 2023, “When Operation Technology Meets Information Technology: Challenges and Opportunities,” Future Internet 15(3):95.

35 A. Thelen, X. Zhang, O. Fink, et al., 2022, “A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twin—Part 1: Modeling and Twinning Enabling Technologies,” Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 65(12):354.

(arising from materials, processes, sensors, etc.) quantification included in the model and parameter reduction process.36

There is a lack of techniques to effectively scale digital twins from “high-fidelity” physics-based models that comprehensively represent the system to “low-fidelity” data-driven models for efficient, real-time model execution, to effectively retain consistency with the physical counterpart (i.e., the physical twin) and the characteristics of real-world data.37

Digital twins will also contain “uneven” levels of fidelity, and it is critical to allow for different levels of information, which can be improved over time. For example, high-value assets such as core machinery or robots in a factory will require more detail and automation than the background walls. In many cases, the asset may have very high-fidelity data and sensing, while the asset’s location data are low fidelity (e.g., a text string “conference room 2980 in building C”) and may vary over time.

Uncertainty Quantification and Handling of Manufacturing Data and Models

Currently, there is a lack of tools that address the process of data curation and the need to systematically and effectively quantify and manage the uncertainty that results from the large volume and variety of data collected from various sensors and other sources during manufacturing processes. These are general purpose tools that are being developed with the Clean Energy Smart Manufacturing Innovation Institute as platform and repeatable information model capabilities for processing data upon collection, ingestion, and contextualization and further processing and categorization if aggregated for collaborative use. The Cybersecurity Manufacturing Innovation Institute is focused on platforms and the security of the data as well as facilitating the opportunities for use.

With respect to AI/ML models, uncertainty can also arise from insufficient data for training (i.e., epistemic uncertainty) or variability that is inherent to certain operations or processes and sensor measurements (i.e., aleatory uncertainty). Data can also be incorrect due to a range or reasons from use in different contexts, sensor drift and failures, human error, and AI hallucination as well as malicious “fake news” and hacking or subversion.

It is important that data privacy and security be core fundamentals to any AI/ML systems but that those systems also retain the ability to modify data and notify systems as well as have a clear escalation process when data errors and breaches

___________________

36 A. Thelen, X. Zhang, O. Fink, et al., 2023, “A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twin—Part 2: Roles of Uncertainty Quantification and Optimization, a Battery Digital Twin, and Perspectives,” Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 66(1):1.

37 Ibid.

occur. To help prevent data error, it is important to have quality labeled data sources and for systems to communicate the level of uncertainty with regard to data quality; when data breaches occur, it is critical to have clear escalation and security policy to reduce the time to resolve, communicate, and fix incidents. Data privacy and security and AI is a rapidly evolving area. Smart manufacturing should build on traditional data privacy, security, and AI best practices and ensure that smart manufacturing scenarios are incorporated and can improve over time as policies and systems advance.

Accordingly, it is important that methods for uncertainty handling such as uncertainty quantification become an integral part of AI/ML research in smart manufacturing. On one hand, addressing epistemic uncertainty (which is commonly referred to as model uncertainty)38 requires systematic procedure for model selection (e.g., determine which AI/ML technique is most appropriate to use) and model parameter calibration during process modeling. It is therefore critical to investigate methods such as Bayesian theory to rigorously quantify model uncertainty, compare suitability among different AI/ML techniques for manufacturing problems of interest, and ultimately minimize uncertainty in model prediction through information aggregation.39,40

On the other hand, aleatory uncertainty, which is associated with the inherent variability of processes and sensor measurements, can be captured by fitting probability distributions to the sensing data.41 Additionally, research effort should be dedicated to determining how aleatory uncertainty is propagated through the process and whether the pattern of uncertainty changes as a function of certain process variables by integrating statistical methods (e.g., heteroscedasticity analysis) into AI/ML techniques.42 Collectively, uncertainty quantification can function as an essential safety layer for AI/ML techniques and enable rigorous risk assessment, leading to more principled decision-making for smart manufacturing.

Methods for uncertainty quantification range from ensembling, which aggregates the outputs of multiple AI/ML models to minimize the uncertainties associated with individual models, to Bayesian theory–based probabilistic modeling,

___________________

38 Ibid.

39 S. Lotfi, P. Izmailov, G. Benton, M. Goldblum, and A.G. Wilson, 2022, “Bayesian Model Selection, the Marginal Likelihood, and Generalization,” Pp. 14223–14247 in International Conference on Machine Learning.

40 Y. Gal and Z. Ghahramani, 2016, “Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation: Representing Model Uncertainty in Deep Learning,” Pp. 1050–1059 in International Conference on Machine Learning.

41 A. Thelen, X. Zhang, O. Fink, et al., 2023, “A Comprehensive Review of Digital Twin—Part 2: Roles of Uncertainty Quantification and Optimization, a Battery Digital Twin, and Perspectives,” Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization 66(1):1.

42 Q.V. Le, A.J. Smola, and S. Canu, 2005, “Heteroscedastic Gaussian Process Regression,” Pp. 489–496 in Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Machine Learning.

which assigns the probabilities to different outcomes from the AI/ML model by means of Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations such that its confidence or uncertainty in making a particular prediction can be assessed.43 Also often applied is sensitivity analysis, which can evaluate the robustness and uncertainty of an AI/ML model’s outputs by varying the inputs to and network parameters of the model. Ultimately, through continued monitoring of an AI/ML model’s outputs in real-world applications and comparing them with evaluations by experts with physical domain knowledge, uncertainties associated with the AI/ML model (e.g., due to changing data distribution from nonstationary dynamics or newly emerging patterns that were not captured during the model training process) can be determined.

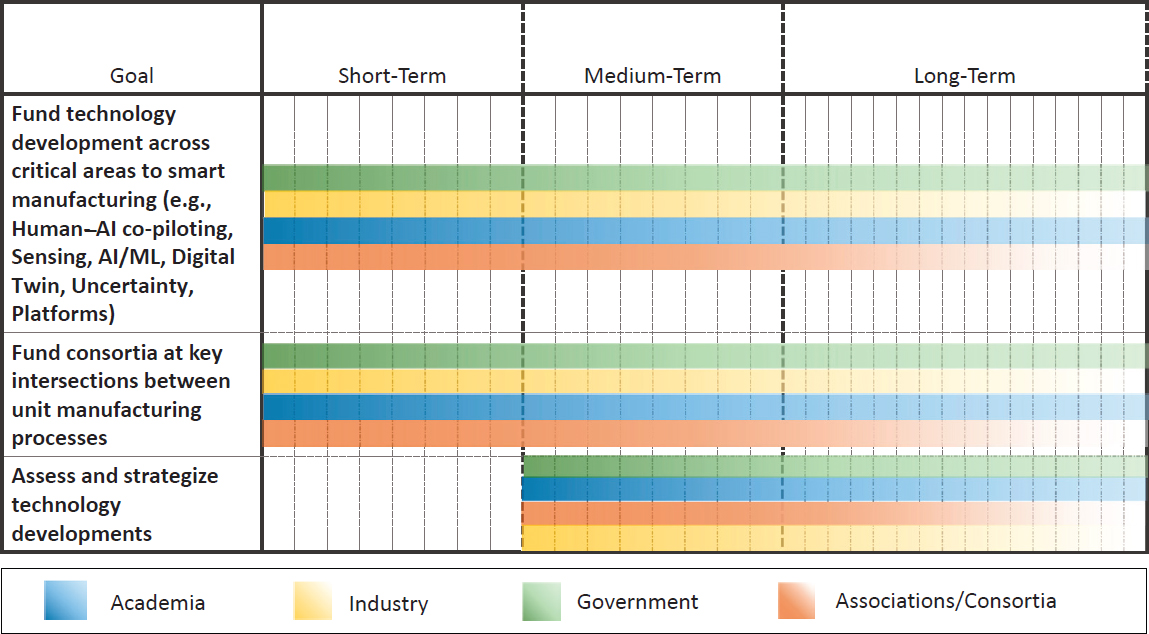

Key Recommendation: Smart manufacturing is multifaceted, and technologies developed in one specialty area most likely will not be suited for other applications. The Department of Energy and other federal agencies should fund programs and consortia that develop technologies at the intersections of critical technologies (e.g., human–artificial intelligence [AI] co-piloting, sensing, AI/machine learning, platform technologies, digital twins, and uncertainty quantification), unit manufacturing processes (e.g., casting, forming, molding, subtractive, additive, and joining), and industry sectors (e.g., semiconductor, aerospace, automotive, biomedical, and agriculture).

Funding Opportunities

Fund Technology Development Cut Across at the Six Critical Areas of Smart Manufacturing

While each area is of importance, the intersections between those areas shall be placed at a higher priority. See a timeline for these efforts in Figure 4-3. The committee considers the short-, medium-, and longer-term timeframes to be in the ballpark of 2, 4, and 6 years, respectively.

Human–Artificial Intelligence Co-Piloting

Establish programs that investigate how humans can maintain situational awareness (self-awareness and situation awareness) in complex smart manufacturing deployments, make informed decisions, and efficiently interact with machines and other coworkers.

___________________

43 S. Lotfi, P. Izmailov, G. Benton, M. Goldblum, and A.G. Wilson, 2022, “Bayesian Model Selection, the Marginal Likelihood, and Generalization,” Pp. 14223–14247 in International Conference on Machine Learning.

Sensing

Promote research that synergistically integrates physical domain knowledge with data-driven methods to ensure consistency between the digital replica and physical counterpart. Explore additive manufacturing for customized sensor housing design to improve adaptivity and accessibility of sensors to the source of signal generation for high-fidelity data acquisition. Encourage the development of robust, reliable, and cost-effective sensors that are closely connected with industrial needs.

Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning

Fund research and development that can reduce the computational cost using advanced AI/ML methods by at least 20-fold while maintaining prediction accuracy within ±5 percent compared to the standard central processing unit–based numerical simulation models so that these models can be effectively integrated to digital twins. Fund research to create AI/ML diagnosis tools validated by data in the data bank. Fund research in generative AI to facilitate smart manufacturing workflow.

Platforms

Continued investment and research in OT/IT integration through platforms and general purpose tools are critical to data, model, and systems engineering of smart manufacturing industry for impact at scale. Platforms bring standards, interconnectedness, tools, discoverability, accessibility, and security to all capabilities, inclusive of all of the above, needed to scale advanced sensing, data, control, modeling, and their orchestration and implementation. Platforms address the increasing complexity of manufacturing digitalization.

Digital Twin

Fund programs that develop the modules for digital twins using the data bank. Use the manufacturing institutes to point manufacturers to use cases where digital twins have been successfully used to reduce startup time, de-bottleneck existing production, or simulate the impact of changes. Use “Lighthouses” across discrete, hybrid, and process control applications to promote real-world uses and outcomes from digital twins.

Uncertainty Quantification

Fund research that develops methods (1) to incorporate uncertainty quantification into the data curation process as part of the data description to ensure data transparency and validity as the basis for informed, robust decision-making; and (2) that efficiently incorporate uncertainty quantification in the modeling process (physics-based models and AI/ML models).

Fund Consortia at Key Intersections

One example is around unit manufacturing processes since they are foundations of the manufacturing enterprise and are connected with upstream and downstream processes. Another example is around a particular industry. These consortia have the needs of all six critical technical areas and can be used as a testbed for these technologies:

- Develop and nurture consortia that specifically set out to establish best practices and standards by studying and implementing digital integration of the end-to-end value stream of the manufacturing workflow under a prescribed set of conditions agreed to by all participants. Ensure representation across manufacturers requiring discrete (automobile manufacturing, logistics, etc.), hybrid (food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, consumer packaged goods,

- etc.), and process (oil and gas, chemicals, mining, semiconductors, etc.) control applications. Utilize the “Lighthouse” concept of reference production facilities and supply chain networks to bring these concepts to life.

- Develop and nurture consortia that address industry business models about intellectual property, trade secrets, data, know-how, and security that are preventing the industry from taking advantage of the full capability of the network as a resource. Develop and nurture consortia that provide toolkits, references, and sources of expertise for developing digital twins of manufacturing processes, including KPIs to gauge increased throughput, flexibility, and worker effectiveness.

- Prioritize consortia that develop and use models and sensors that will track embodied energy, emissions, and cyber-physical risk at several levels of the manufacturing ecosystem such as product, process, facility, and supply chain. Cyber-physical passports will enable such quantification frameworks.

- Engage the Manufacturing USA institutes for a stronger role in disrupting and reinventing industry business and technology for the broader future of smart manufacturing by taking on larger scoping challenges—for example, evaluating cybersecurity readiness, connectivity index, or autonomy index.

Overall, this chapter makes three key recommendations two of which are illustrated in Figure 4-4.