Defining and Evaluating In-Home Drug Disposal Systems For Opioid Analgesics: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 5 Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS)

5

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS)

Highlights of Key Points Made by Lynn Mehler

- A risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) is a tool that can be used to mitigate serious safety risks of a product to the extent necessary for the product to be approvable.

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has the authority to require a REMS as part of product approval as well as at any time after approval, and to require the inclusion of specific elements to assure safe use.

- FDA’s expanded REMS authority under the SUPPORT Act allows the agency to require interventions (e.g., packaging, disposal systems) to mitigate a serious risk.

- The product sponsor is responsible for ensuring the compliance of prescribers, dispensers, and patients with the REMS.

Presented by Lynn Mehler, June 27, 2023.

Lynn Mehler, partner at Hogan Lovells LLP, practice area lead for pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, provided a legal and practical overview of REMS.

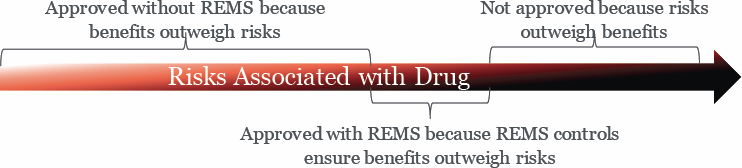

FDA can require a REMS “if it determines that it is necessary to mitigate a specific risk to ensure the product benefits outweigh its risk,” Mehler said. In essence, a REMS is a tool that can be used to mitigate seri-

NOTE: REMS = risk evaluation and mitigation strategy.

SOURCE: Presented by Lynn Mehler, June 27, 2023.

ous safety risks of a product to the extent necessary for the product to be approvable (Figure 5-1).

In considering whether to require or modify a REMS, FDA is required by statute to “consider whether the REMS unduly burdens patient access and attempt to minimize the burden on the health care delivery system,” Mehler said. FDA has the authority to require a REMS as part of product approval as well as at any time after approval, and to require the inclusion of specific elements to assure safe use (ETASU). ETASU can include requirements for certification of prescribers and pharmacists, conditions for dispensing “only in certain health care settings” or “only with documentation of safe-use conditions,” and requirements for patient monitoring and enrollment in a registry.

All REMS must be assessed periodically to ensure they continue to meet the stated goals and consider whether modifications are needed. Mehler described this as an “iterative [and] complicated process.” If the sponsor is found to be out of compliance with the REMS requirements, the drug is considered to be misbranded, and FDA will take enforcement action, which can include “civil monetary penalties, withdrawal of approval, or criminal liabilities.”1 Per the statute, the sponsor is responsible for ensuring the compliance of prescribers, dispensers, and patients with the REMS. Mehler said there is a process for handling noncompliance by stakeholders (with decertification of prescribers or dispensers only as a “last resort”).

___________________

1 Mehler explained that “a drug is misbranded if its label or labeling are false or misleading in any way (including REMS materials).”

REMS FORMAT AND CONTENT

A REMS has two main parts, the REMS document and associated materials, and the REMS supporting document. “The REMS document establishes the goals and requirements of the REMS [and] describes the elements of the REMS and specific steps for each stakeholder to mitigate the serious risk of the drug,” Mehler said. The REMS materials include other documents that FDA has approved for use in meeting the REMS requirements (e.g., certification forms, enrollment forms, educational materials).

The REMS document and materials for all approved REMS are publicly available on the FDA website.2 Mehler added that the REMS document and materials are enforceable by FDA and cannot be changed without the agency’s approval (see REMS modifications, below).

The REMS supporting document is the sponsor’s plan for how it will meet the requirement in the REMS document, “and includes the rationale for the design, implementation, and assessment of the REMS,” Mehler said. The supporting document is reviewed by FDA during the REMS approval process and when changes are made. REMS supporting documents are not publicly disclosed.

REMS MODIFICATION

The agency or the sponsor can request modifications to the REMS. FDA might suggest that the sponsor consider making a modification, or the agency can issue a formal request for modification via a letter to the sponsor with a specified time period for response, which Mehler said per the statute is “120 days or a reasonable time.”

Mehler referred participants to the FDA guidance for industry on REMS modifications and revisions.3 Editorial revisions that are minor changes to the REMS (e.g., an address change) can be made with notification to FDA. Major modifications to a REMS are changes to the document or materials that are related to product safety or to stakeholder actions required for compliance with the REMS. For example, adding or removing a REMS element or tool is a major change. All major changes must be submitted to FDA as a Prior Approval Supplement and must contain the rationale for the modification, she said. Prior Approval Supplements for major changes are reviewed by FDA within 6 months of receipt by the agency. The statute also includes provisions for dispute resolution if needed, she said.

___________________

2 See https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm (accessed November 18, 2023).

3 See https://www.fda.gov/media/128651/download (accessed November 18, 2023).

OVERLAPPING STATUTORY AUTHORITIES FOR CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

Opioids are subject to both controlled substances obligations and REMS obligations. DEA is responsible for implementing controlled substances regulations under the Federal Controlled Substances Act. Controlled substances are also subject to state-controlled substance laws and regulations. Mehler pointed out that for controlled substances, “the DEA statute is the floor,” and states can implement additional or more restrictive regulations. FDA is responsible for implementing regulations and guidance under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which includes authority to establish product–drug specific obligations via a REMS. By contrast to DEA, FDA regulation preempts state regulation.

DEA statute requires registration of activities and locations that “physically touch the drug,” Mehler explained (e.g., manufacturing, warehousing, distribution, dispensing, administering). There is no specific requirement for the drug sponsor to register, and if the sponsor outsources all activities, it is not a DEA registrant, she said. Under FDA regulations, the drug sponsor is always the responsible party for compliance and assessment, regardless of whether it is directly involved in an activity or if the activity is outsourced.

Complying with FDA, DEA, and multiple state regulations can be challenging for sponsors. Mehler said it had long been unclear “where FDA’s authority ended and DEA’s started” regarding mitigating abuse and the risks associated with diversion. However, since 2008, “REMS authority specifically allows FDA to require a REMS for [adverse events] that are overdose, abuse, and withdrawal,” she said.

SUPPORT ACT PROVISIONS

As discussed, FDA’s REMS authority was expanded under the SUPPORT Act, giving the agency authority to require interventions (packaging, disposal systems) to mitigate a serious risk. Mehler pointed out that one challenge when developing a REMS is when the risk is associated with a subset of patients or conditions. Language in the law allows FDA to require these interventions “for certain patients.” SUPPORT Act provisions also require FDA to consider patient access to the drug, the burden on health care systems, and compatibility with established systems when establishing REMS requirements. In addition, the “agency must consult with other federal agencies with authority over drug disposal packaging,” Mehler said.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Mehler discussed the following three categories of practical considerations for implementing opioid disposal systems under a REMS:

- Will it work? Considerations listed by Mehler included whether the disposal system meets the DEA standard for rendering the drug unretrievable, whether patients understand how to use it and whether they actually use it, whether it is practical to use across the wide range of settings and conditions where opioids are used, and how to determine which systems are effective and how to regulate these systems.

- Will it be unduly burdensome? It is important to consider the potential burdens that use of a disposal system might impose on patients with short-term prescriptions as well as on those taking opioids to manage chronic pain, and how use of the disposal system would impact the health care system, including pharmacies. Mehler also highlighted the need to consider the potential burden for opioid drug manufacturers who must supply the disposal systems (e.g., costs) and whether those burdens might impact their ability to continue to supply the market and meet the opioid product needs of patients.

- Will there be unintended consequences? The impact of drug disposal systems on the environment is one potential unintended consequence that has been discussed throughout the workshop. Another consideration is the potential for determined drug seekers to find ways to identify containers with disposed opioids and access them, Mehler said.

This page intentionally left blank.