Defining and Evaluating In-Home Drug Disposal Systems For Opioid Analgesics: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 Life Cycle of Prescribed Opioids

2

Life Cycle of Prescribed Opioids

Highlights of Key Points Made by Robert Hoffman

- Patients are frequently prescribed more doses of an opioid than needed to manage acute or postoperative pain.

- Patients tend to keep unused opioid medication in the home, and most are not securely stored.

- Unused prescription opioids have perceived value associated with the costs of obtaining them and the patient’s perception of potential future need.

- Access to opioid analgesics can facilitate non-medical use, diversion, and misuse with potentially fatal outcomes, especially for children who ingest adult doses.

- Disposal options are available, but people must be willing to give up a product they perceive as useful and for which they have paid.

Presented by Robert Hoffman, June 26, 2023.

Ideally, patients would be prescribed the exact amount of opioid medication needed for management of their pain, they would use all the pills, and they would discard the empty bottle, said Robert Hoffman, professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine. In reality, he says, “patients are

frequently prescribed more doses than needed.” The unused portion of a prescription has perceived value for many patients, even if it is no longer needed, because of the cost spent to obtain it (including money and time spent to obtain the product itself and the visit to the prescribing provider). Patients tend to keep unused opioid medication in the home, not unlike one might freeze uncooked hamburgers from a barbecue for later use, he suggested. Although harm reduction medicine storage options are available, such as locking pouches or storage cabinets, most unused opioids are simply kept in the bathroom medicine cabinet where they are accessible to anyone who lives in or enters the home.

NON-MEDICAL USE

Easy access to unused opioid medication is a facilitator of non-medical use. Hoffman defined non-medical use as “any use of a prescription product by any individual for the non-intended purpose.” This includes use of the prescription product in a different manner, for a different reason, during a different time period, or by a different person than originally prescribed. Examples of non-medical use include using one’s own prescribed pain medications to treat pain unrelated to the original prescription, as well as taking another person’s unused prescription pain medication for pain relief. He emphasized that non-medical use is potentially fatal. Children are at very high risk of death when exposed to adult doses of opioids, and disparities in child death rates persist, with Hispanic and Black children at increased risk (West et al., 2021).

DIVERSION AND MISUSE

Diversion is when prescription opioids enter the illegal drug market. Diversion can happen anywhere along the product supply chain, including when the patient or someone else with access sells unused prescription opioids to someone else. Hoffman noted that harm reduction approaches such as locked medication pouches or cabinets can be a deterrent to diversion, although it could be the one diverting the product. These harm reduction measures can also be overcome by someone who really desires access.

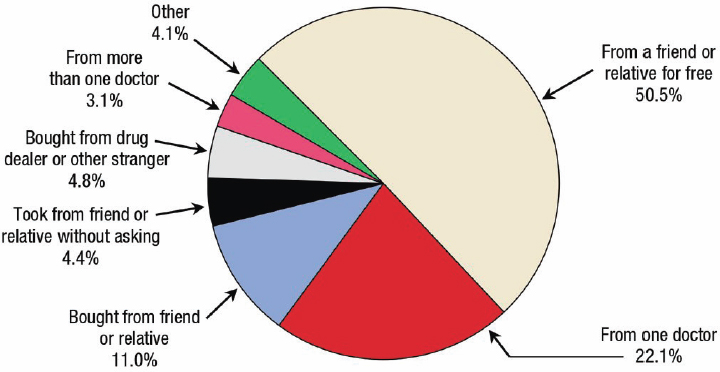

Hoffman described misuse of opioids as beyond non-medical use, resulting in a cycle of use that can lead to opioid use disorder. “The vast majority of people who misuse prescription drugs get them from someone they know … whether or not there is money involved,” Hoffman said (Figure 2-1). The 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reported that 1.6 million people misused a prescription opioid medication for the

SOURCES: Presented by Robert Hoffman, June 26, 2023; Lipari and Hughes, 2017.

first time that year.1 Hoffman pointed out that “had it not been available to them, it couldn’t have possibly been misused.” State-level data on opioid dispensing rates for 2019 suggest that dispensing is highest in six states in the Southeastern United States: West Virginia, Tennessee, Alabama, Missouri, Louisiana, and Arkansas. County-level data, however, clearly show that high levels of dispensing are occurring in pockets of every state, affecting communities nationwide.

DRUG DISPOSAL

Hoffman presented a graphic from FDA with information for the public on three options for disposing of unneeded medication.2 FDA wants the drugs to be brought to a drug take-back location if available (e.g., on national prescription take-back days, in permanently installed drop boxes). Otherwise, drugs should be flushed if they are on the “FDA flush list” or disposed of in the trash after following instructions for making them unpalatable.

For all disposal options, people must be willing to give up a potentially useful product they have paid for, he reiterated. Although these options seem simple, Hoffman said people often do not understand the directions (e.g., people will put full, closed pill bottles in coffee grounds,

___________________

1 See https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2019-nsduh-annual-national-report (accessed November 18, 2023).

2 See https://www.fda.gov/media/111887/download (accessed November 18, 2023).

rather than loose pills). Furthermore, drugs that are flushed or sent to the landfill can contaminate drinking water; opioids have been detected in drinking water samples from across the United States (Skaggs and Logue, 2022). A variety of in-home disposal options are also available, ranging widely in price and ease of use.

INTERVENTION POINTS

Hoffman discussed three points in the life cycle of a prescribed opioid where intervention could prevent adverse outcomes. “Putting the drug out there is the biggest problem,” Hoffman said. Appropriate prescribing for pain management can be challenging (which product, how much, for how long). Clinicians must balance reducing unnecessary use with giving patients the pain relief they need. Better non-opioid pain management approaches are needed, he said.

Another point for intervention is home storage of opioids, especially for patients who maintain a supply of opioid medication to manage recurrent or chronic pain, Hoffman said. Risk prevention interventions include secure home storage options and having naloxone available to treat exposures.

The intervention point germane to this workshop is disposal of unused product. Hoffman suggested that in-home disposal systems as an intervention are most likely to be taken up by people who are or can be informed about the risk and/or who are socially conscious. In his practice he has found that it is easier to make the argument for opioid disposal when there are children or teens in the home. It is potentially more difficult to convince patients who face barriers to acquiring the drug to dispose of unused product. Examples of such barriers include cost, health insurance coverage, and geographic location/rurality.

Hoffman reiterated that a significant challenge for uptake and use of in-home disposal systems is convincing people to discard something they paid for, even if they no longer need it. People want self-determination and “expect that they’ll have pain in some future moment,” he said. He suggested that part of the solution is making health care affordable and accessible to everyone, which he acknowledged is far beyond the scope of this workshop.

There is unlikely to be a one-size-fits-all model for safe opioid disposal, and Hoffman offered several considerations for the development of in-home opioid disposal systems. First, what would motivate people to dispose of something they might consider to be of value, and what type of disposal systems would be acceptable and affordable for users? For the systems themselves, is the device efficient and effective in removing the drug from the community, is it cost effective, and what is the final disposition of the drug in the environment?