Developing and Assessing Ideas for Social and Behavioral Research to Speed Efficient and Equitable Industrial Decarbonization: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 9 Considering Firm and Industry Responses to Decarbonization Goals

9

Considering Firm and Industry Responses to Decarbonization Goals

The final panel provided a comprehensive examination of firm- and industrial-level responses, corporate governance, and organizational strategies concerning decarbonization goals. Encompassing perspectives drawn from small, medium, and large manufacturers; nonindustrial corporations; and financial institutions, the panel discussed key social science research needs to better understand and inform decarbonization-related business decisions. Planning Committee Member Udayan Singh, Energy Systems Analyst at Argonne National Laboratory, moderated the discussion with the collective aim of providing insights into the broader discourse on sustainable industrial decarbonization.

DRIVING DECARBONIZATION: THE ROLE OF POLICY ON ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR

Nicole Darnall, Foundation Professor at Arizona State University and Director and co-founder of Arizona State University’s Sustainable Purchasing Research Initiative, suggested that when considering how firms address decarbonization goals, the role of policy as an action-encouraging catalyst is important to consider. While there are a number of companies actively pursuing net-zero targets, she pointed out that they represent a minority of organizations engaged in decarbonization efforts. The momentum to decarbonize is intensifying, she said, both in the United States and on a global scale, with policy measures accelerating this trend.

Darnall referenced a series of enacted executive orders1 designed to urge federal agencies to address the climate crisis domestically and internationally and also to assess climate-related financial risks. Specifically, she noted electric vehicle-related infrastructure provisions within the Inflation Reduction Act,2 prompting federal facilities to prioritize decarbonization efforts. Additional efforts aim at fundamentally altering federal acquisition processes to incorporate sustainability considerations. She mentioned that the U.S. General Services Administration

___________________

1 The executive orders (EOs) Darnall referenced included EO 14008: Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad (https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/executive-order-on-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad/); EO 14030: Executive Order on Climate-Related Financial Risk (https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/05/20/executive-order-on-climate-related-financial-risk/); and EO 14037: Executive Order on Strengthening American Leadership in Clean Cars and Trucks (https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/08/05/executive-order-on-strengthening-american-leadership-in-clean-cars-and-trucks/).

2 More information about the Inflation Reduction Act is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/cleanenergy/inflation-reduction-act-guidebook/

established a new federal advisory committee3 whose purpose is to integrate sustainability measures into federal procurement processes, noting this as the first specific examination of the federal government’s supply chain in terms of decarbonization. The objective is to achieve net-zero emissions in the federal procurement process and the approach, she suggested, could have substantial ramifications for firms, both in the United States and globally. Similar initiatives are underway in the European Union, in international governance bodies like the United Nations, and in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,4 as well as in individual countries promoting sustainable procurement.

Alongside procurement, Darnall noted the need to heighten emphasis on sustainability standards and reporting. She mentioned a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission5 rule regarding climate-related disclosures, along with increased attention to climate disclosure laws in California and similar efforts in the European Union and Canada. While these efforts may seem disparate, she emphasized their interconnection. Firms navigating these requirements face complexities—for example, to qualify as a federal supplier, firms are required to adhere to sustainability standards and reporting.

Darnall highlighted the significance of sustainability reporting, which primarily involves disclosing risks within a firm’s operational landscape. She noted a frequent lack of emphasis on actual performance metrics within companies. While companies may be required to set targets, she explained, there is no universal standard dictating what those targets need to entail. Furthermore, she continued, limited attention may be given to monitoring and conformance expectations, which complicates efforts to combat greenwashing. She emphasized that, overall, the situation is challenging to navigate.

Darnall acknowledged that most disclosure requirements exclude small- and medium-sized enterprises, which currently constitute the bulk of carbon emitting entities. When firms announce their net-zero pledges, she noted, they often overlook Scope 3 emissions6 and in some cases a significant fraction of a company’s carbon emissions may be linked to their purchasing choices.7

Darnall pointed out that the increased focus on sustainability standards and reporting is driven not only by the belief that firms’ sustainability performance will improve as a result, but also by the belief that the market will reward such efforts. However, research conducted with her colleagues in the United Kingdom suggested that the situation is more complex.8 While firms adopting sustainability standards and reporting do initially receive market rewards, she noted a threshold beyond which these rewards diminish over time despite ongoing improvements in sustainability performance. This discrepancy—termed the “penalty zone”—acts as a disincentive for firms to further decarbonize because they fail to achieve expected marketplace rewards. She noted that this reveals a flaw in the belief that this approach to sustainability standards and reporting will drive meaningful improvements.

Current discourse on decarbonization has prompted Darnall to explore how firms are addressing Scope 3 emissions within their supply chains—a crucial yet often overlooked aspect of carbon reduction efforts. She observed a pressing need to incentivize firms to provide accurate emissions data, since potential disincentives to disclosure currently exist. Additionally, she noted the need to develop partnerships that enable seamless data integration across the supply chain, facilitating genuine decarbonization outcomes. Darnall suggested that a conscious focus on the supply chain is essential to effectively tackle carbon emissions.

She observed that organizations often have pressing internal questions demanding attention (e.g., fostering a sustainability-oriented culture and incentivizing innovative thinking) alongside ongoing external efforts. She proposed the need to both promote systems thinking beyond simple reporting requirements as well as to encourage

___________________

3 More information about the General Services Administration’s Acquisition Policy Federal Advisory Committee is available at https://www.gsa.gov/policy-regulations/policy/acquisition-policy/gsa-acquisition-policy-federal-advisory-committee

4 More information about the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is available at https://www.oecd.org/

5 U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2024, March 6). SEC adopts rules ot enhance and standardize climate-related disclosures for investors. https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2024-31

6 More information about Scope 3 emissions is available at https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/scope-3-inventory-guidance

7 CDP & Capgemini Invent. (2023). From stroll to sprint. https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/cms/reports/documents/000/007/198/original/CDP_Capgemini_report_July_13_From_Stroll_to_Sprint_-_A_race_against_time_for_corporate_decarbonization.pdf?1689231333

8 Darnall. N., Iatridis. K., Kesidou, E., & Snelson-Powell, A. (2023). Penalty zones in international sustainability standards: where sustainability doesn’t pay. Journal of Management Studies, Early View. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12975

adoption of advanced analytical tools for informed decision making. Learning from industry leaders is pivotal in effectively addressing these internal challenges, she noted.

Darnall emphasized that, by exploring various research avenues, social scientists can aim to shrink the penalty zone, to ensure that market performance aligns with a firm’s sustainability efforts. This entails shifting focus towards actual performance outcomes rather than adhering solely to process conformance expectations outlined in sustainability reporting. Additionally, she noted the need for solutions to be practical and scalable. In her concluding remarks, Darnall said one possible approach could involve integrating engineering models with social science models to ensure that climate technologies are effectively implemented and contribute to emissions reduction.

INTEGRATING SOCIOLOGICAL, BEHAVIORAL, AND PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVES INTO A FIRM’S DECARBONIZATION ACTIONS

Pavitra Srinivasan, senior manager in the Industry Program and co-leader of the Embodied Carbon Initiative at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, noted the importance of incorporating public health considerations into multi-disciplinary discussions, highlighting the absence of these considerations in the prior day’s conversations. Including public health considerations could be crucial to comprehensively addressing various issues and ensuring effective multi-disciplinary responses. She suggested that public health concerns play a significant role in industrial decarbonization efforts, particularly through the emphasis on social and behavioral factors. Leveraging tools, methodologies, and perspectives from public health, she noted, could provide valuable insights and approaches to addressing various challenges associated with industrial decarbonization.

Srinivasan observed that social science and management literature—as well environmental, social, and governance (ESG) studies—contain valuable perspectives on factors influencing a firm’s decision to transition between business models. While new technologies may offer economic and technical promise, she noted that their adoption and success can be uncertain due to factors such as shifting social norms, market dynamics, and/or government incentives.9 Barriers to the adoption of new technologies, she continued, can include a lack of legitimacy as well as pre-existing inhibitive institutional approaches and opposing behavior of establish suppliers. As examples, she mentioned consumer behavior studies, such as the cement industry, in which engrained norms and practices and the dominance of traditional technologies can hinder acceptance of innovative low-carbon alternatives.10

Srinivasan suggested that social factors may play a more significant role in decarbonization efforts than technical or economic factors both at the consumer and industrial levels and especially in large-scale market adoption or transformation.11 Social factors include the level of technological acceptance within a group or amongst individuals, which can be influenced by group characteristics such as size, location, and management styles. Additionally, she noted, acceptability of technologies is shaped by industrial communities’ social contexts—including the influence of leaders, individuals, social networks, and communication channels, as well as awareness/level of education and institutional or geographic contexts.12 Considered collectively, these elements could contribute to the degree of adoption and success of new technologies.

Shifting focus to management perspectives, Srinivasan referenced the new “theory of the firm,” which redefines corporate business models to encompass socio-economic systems aiming to generate value both internally

___________________

9 Hess, D. J. (2005). Technology- and product-oriented movements: Approximating social movement studies and science and technology studies. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 30(4), 515–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243905276499

10 Reddy, S., & Painuly, J. P. (2004). Diffusion of renewable energy technologies—barriers and stakeholders’ perspectives. Renewable Energy, 29(9), 1431–1447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2003.12.003

11 Arkesteijn, K., & Oerlemans, L. (2005). The early adoption of green power by Dutch households: An empirical exploration of factors influencing the early adoption of green electricity for domestic purposes. Energy Policy, 33(2), 183–196 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(03)00209-X; Caird, S., Roy, R., & Herring, H. (2008). Improving the energy performance of UK households: Results from surveys of consumer adoption and use of low-and zero-carbon technologies. Energy Efficiency, 1, 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12053-008-9013-y

12 Wolfe, A. K., Bjornstad, D. J., Russell, M., & Kerchner, N. D. (2002). A framework for analyzing dialogues over the acceptability of controversial technologies. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 27(1), 134–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439020270010

and externally.13 She said that another possible approach to deep decarbonization lies in risk management, which is crucial for both ensuring long-term sustainability and guiding a firm’s decision-making processes.14 She suggested that socio-technical imaginaries, as well as carbon handprints—which are similar to carbon footprints but emphasize positive actions—can offer valuable insights. Carbon handprints,15 rooted in lifecycle- and social lifecycle-assessment principles, provide a framework for firms seeking to make decarbonization decisions by assessing the positive societal impacts of their actions. She noted the particular relevance to the cement and steel industries, which have inherent emission profiles that can be offset through initiatives like Community Benefits Plans (CBPs),16 thereby balancing their negative impacts with positive societal contributions.

In a qualitative study focused on behavioral aspects of the cement industry’s adoption of renewable energy innovations, Srinivasan and her colleagues emphasized the feasibility of a novel electrochemical decarbonization technology.17 Using ethnographic case study methods, they interviewed stakeholders from various sectors including cement companies, trade associations, government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and research institutions across multiple countries. Their findings highlighted the significance of social, technical, environmental, economic, and regulatory factors (STEER factors), which influence adoption of new technologies by industrial firms. She noted that STEER factors were analyzed within the framework of socio-technical theories such as social practice theory, the PACT framework,18 and diffusion of innovation theories.19 She suggested that this research is a valuable aid for explaining industrial behavior.

The study also found that social factors within companies significantly influence decision-making processes—including the company’s stance on change, environmental impacts, and corporate image, as well as management’s attitudes, knowledge, and leadership style. Srinivasan said that individual actions—both inside and outside a company—were also influenced by these factors and the social networks in which they are embedded. She noted that social networks, which exist within and across firms, play a crucial role in technology adoption, attitude formation, management decisions, and partnership building.20 The study revealed an interesting tension between homophily—similarity in thinking—and heterophily—diverse perspectives coexisting within the same network—in impacting decision-making processes. She noted that findings reaffirmed the expected roles of economic, technical, and institutional factors in shaping decisions.

Delving into firms’ reactions to financial incentives for decarbonization, Srinivasan explored whether they perceive “carrots” or “sticks” as more effective. She remarked on a significant response from firms regarding financial incentives for decarbonization but explained that observations are somewhat anecdotal and still emerging. For instance, she mentioned a notable surge in interest regarding funding opportunities made available through the Department of Energy and initiatives like the Inflation Reduction Act, particularly within sectors like cement. She commented that this interest reflects a willingness among firms to engage in public-private partnerships and access funding through cost-sharing mechanisms. For firms with long lifespan manufacturing plants (24–50 years) or substantial capital investments, she suggested such arrangements offer a stabilizing factor in uncertain decision-making contexts. While this approach may incentivize many firms to partake in industrial decarbonization efforts, it

___________________

13 Alvarez, S. A., Zander, U., Barney, J. B., & Afuah, A. (2020). Developing a theory of the firm for the 21st century. Academy of Management Review, 45(4), 711–716. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2020.0372; Business Roundtable. (2019, August 19). Business roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote ‘an economy that serves all Americans’. https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans

14 Lempert, R. J., & Trujillo, H. R. (2018). Deep decarbonization as a risk management challenge [Perspective]. Rand Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE300/PE303/RAND_PE303.pdf

15 Norris, G. (2021) Research brief #1: What are handprints? Sustainability and Health Initiative for NetPositive Enterprise, MIT. https://shine.mit.edu/sites/default/files/RB1%20What%20are%20Handprints%2003032021_1.pdf

16 More information about CBPs is available at https://www.energy.gov/infrastructure/about-community-benefits-plans

17 Failey, T., & Srinivasan, P., & McCormick, S. (2014, August 16–19). Adoption of renewable energy innovations in the cement industry. American Sociological Association’s 2014 Annual Meeting San Francisco, California, United States. https://www.asanet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014_am_final_program_c_optimized.pdf

18 Wolfe, A. K., Bjornstad, D. J., Russell, M., & Kerchner, N. D. (2002). A framework for analyzing dialogues over the acceptability of controversial technologies. Science Technology and Human Values, 27(1), 134–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/016224390202700106

19 Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

20 Bossink, B. (2004). Managing drivers of innovation in construction networks. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 130(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364

may not appeal to all, she noted, particularly those reluctant to contend with noneconomic requirements—perceived as potential “sticks”—that may need to be met in public-private partnerships.

Srinivasan observed that to avoid associated risks some firms have opted to pursue decarbonization technologies independently, rather than engaging in potential public-private partnerships. In this context, a notable development involves Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s (METI’s)21 2023 release of a transition finance roadmap for industrial decarbonization.22 She said this roadmap, starting with the iron and steel sector, employs a mix of incentives and penalties designed to drive decarbonization efforts. While the effectiveness of such approaches requires further assessment, she added that this roadmap offers comprehensive insights into the interplay of incentives and disincentives.

Next, Srinivasan discussed the impact of the “green premium” on firm-level behavior. Directing her attention to recent research investigating the pressure that market and “economic uncertainty put on sustainable behavior change,” she referenced research from the Brookings Institute echoing similar sentiments at the firm level.23 Past studies yielded conflicting conclusions on whether less climate friendly “brown” stocks offer higher returns compared to “green” stocks—or vice versa. She said a new analysis, leveraging international evidence and diverse methodologies using carbon emissions as a measure of “greenness,” has shed light on this issue. The findings, she noted, indicate that across G7 countries “green” stocks have generally yielded higher returns for the better part of the last decade. However, amid the energy crisis in early 2022, “brown” stocks outperformed “green” ones. She noted that this underscores how economic uncertainty puts pressure on sustainable behavior change and results in a greater reliance on less climate friendly choices.24

Finally, on the subject of research priorities, Srinivasan observed the need to focus on enabling firms to navigate decisions amidst deep uncertainty and nonlinear risks. Such enabling includes evaluating trade-offs and identifying effective incentives with a particular emphasis on small- to medium-sized manufacturers, which constitute a significant portion of the industrial supply chain. To conclude, she mentioned the importance—spanning across small, medium, and large firms alike—of exploring the influential role of social networks and the potential for leveraging pivot points to enhance decision making.

INSIGHTS FROM CORPORATE INITIATIVES AS WELL AS STATE AND CITY CLIMATE ACTIONS

Thomas Lyon, Dow Chair of Sustainable Science, Technology and Commerce, with appointments in both the Ross School of Business and the School of Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan, presented recent research25 focusing on understanding the factors that influence carbon emission reductions in manufacturing facilities. Analyzing data from the CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project)26 covering manufacturing facilities across the United States from 2010–2019, the study focused on three main categories of action: corporate initiatives, state-level climate policies, and city climate action plans. The research stands out as an early attempt to delve into facility-level data from CDP, Lyon said, rather than focusing solely on corporate-level information. Notably, CDP data provided insights into both Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, although they lacked comprehensive coverage of Scope 3 emissions for all firms. The most common corporate decarbonization initiatives reported to CDP included the energy efficiency of buildings, production process energy efficiency, transportation fleet

___________________

21 More information about METI is available at https://www.meti.go.jp/english/index.html

22 More information about METI’s roadmap is available at https://www.meti.go.jp/english/policy/energy_environment/transition_finance/index.html

23 Bauer, M. D., Huber, D., Rudebusch, G. D., & Wilms, O. (2023, January 12). Where is the carbon premium? Global performance of green and brown stocks (Hutchins Center Working Paper No. 83). Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/where-is-the-carbon-premium-global-performance-of-green-and-brown-stocks/

24 Pleter, L., Cascone, J., Pankratz, D., & Novak, D. R. (2023, July 25). Economic uncertainty puts pressure on sustainable behavior change. Deloitte Insights. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/environmental-social-governance/sustainable-consumer-behaviors.html

25 Leffel, B., Lyon, T. P., & Newell, J. P. (2024). Filling the climate governance gap: Do corporate decarbonization initiatives matter as much as state and local government policy? Energy Research & Social Science, 109, 103376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103376

26 More information about CDP is available at https://www.cdp.net/en

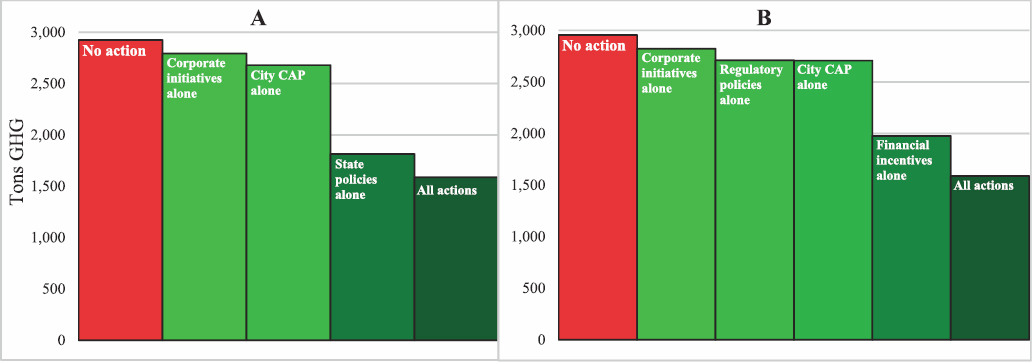

SOURCE: Leffel, B., Lyon, T. P., & Newell, J. P. (2024). Filling the climate governance gap: Do corporate decarbonization initiatives matter as much as state and local government policy? Energy Research & Social Science, 109, 103376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103376. Reprinted with permission.

improvements, low carbon energy purchases, installation of low carbon energy systems, green project financing, and reductions in fugitive emissions.

In examining subnational policies, Lyon noted that approximately 30% of U.S. cities have state climate action plans.27 These data, collected by Benjamin Leffel, are the first attempt to analyze subnational policy information, although detailed plan-related implementation specifics are not available.28 State climate policies were assessed using the Database for State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency,29 which categorizes policies into financial incentives and other regulatory measures.

Lyon explained that the study incorporated several control variables, including per capita income, the presence of environmental nongovernmental organizations in the area, the percentage of Democratic Party voters, and corporate tax rates. Lyon noted that findings are summarized in straightforward graphs designed to provide a clear, easily understandable message.

Lyon pointed out that, in Figure 9-1, Graph A compares the average greenhouse gas emissions reduction per facility with the potential reduction if no action were taken (represented by the red bar). Various types of initiatives are then categorized based on the reduction each could achieve if implemented alone over a decade. Lyon suggested corporate initiatives alone could lead to a meaningful but modest reduction of around 10% of greenhouse gas emissions. Although city climate action plans show a similarly modest impact, he noted that state policies demonstrate the most significant potential impact, with reductions ranging from 25–30%. When all initiatives are combined, substantial reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are evident at the individual facility level.

Graph B replicates the approach of Graph A, Lyon pointed out, but distinguishes between regulatory policies and financial incentives at the state level. The analysis, he commented, reveals that state-level financial incentives have a significantly greater impact, indicating their effectiveness in driving emissions reductions compared to regulatory policies.

Delving into the effects of Scope 1 versus Scope 2 emissions using CDP data, Lyon said, yields noteworthy insights. City climate action plans emerged as the sole factor significantly impacting Scope 1 emissions reductions.

___________________

27 More information about U.S. state climate action plans is available at https://www.c2es.org/document/climate-action-plans/

28 Leffel, B. (2022). Title: Climate Action Plan adoption for 176 U.S. cities, 2010–2019 [Data set]. University of Michigan Library, Deep Blue Data. https://doi.org/10.7302/2vm5-h202

29 More information about the Database for State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency is available at: https://www.dsireusa.org/

He observed that this result could be attributed to the efforts of cities to directly address local emissions. On the other hand, he noted, corporate initiatives had a notable effect only on Scope 2 emissions reduction.

Several impactful initiatives were uncovered, Lyon mentioned, particularly with regard to the energy efficiency of buildings and production process efficiency, indicating the initiatives’ effectiveness in reducing emissions. Moreover, firms with a larger number of facilities exhibited faster reduction rates, he pointed out, hinting at potential learning effects or economies of scale. State climate policies, while primarily affecting Scope 2 emissions, proved to be the most influential overall. He noted that their direct impact was observed through improvements in the cleanliness of the electricity utilized by these firms.

Noting how city climate action plans directly impact local emissions at the Scope 1 level, Lyon said that ongoing research with his colleague Glen Dowell aims to incorporate pricing mechanisms into the analysis. Commenting on how factors such as carbon taxes, natural gas costs, policy frameworks, and political dynamics are being considered for their potential influence on emissions reduction efforts, Lyon emphasized that this research, utilizing data from the U.S. Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program30—focuses solely on Scope 1 emissions.

Lyon noted an analysis, drawing on about a decade of data, that incorporates variables such as local GOP vote share to assess their impact on emissions reduction.31 He observed that basic economic drivers, including output and carbon prices, have exerted an influence, although he noted that their influence is limited due to relatively low carbon prices in the United States. State policies emerged as the most significant factor driving emissions reduction, particularly in the context of Scope 1 emissions. This suggests a potential shift, induced by state policies, towards electrification. Lyon also noted the presence of a notable partisan effect, with facilities in Democratic-leaning counties demonstrating faster reduction rates compared to those in Republican-leaning counties. Further investigation is underway to clarify the underlying reasons behind this party-related disparity.

EXPLORING THE IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL, AND GOVERNANCE METRICS AND FINANCIAL INCENTIVES ON INDUSTRY-LEVEL EMISSIONS REDUCTION

Singh remarked that panelists explored factors influencing emissions reduction at the industry level. With regards to ESG metrics—particularly pertaining to sustainability-linked loans—Singh raised two questions: Does the availability of low-cost financing affect corporate behavior, and are financial institutions considering reduced interest rates based on a company’s strong ESG metrics?

Darnall responded that one aspect to consider is the relationship between sustainability reporting, which is integral to ESG practices. While there may be a correlation between ESG reporting and certain outcomes, she noted the importance of approaching this correlation with a critical mindset. She emphasized that it is crucial to scrutinize both the factors being reported and what may lie beyond the boundaries of reporting. Even if ESG reporting does have an impact, she said, it may influence only a small fraction of the firms that are actively reporting. She suggested that, for these reasons, it is essential not only to broaden the focus to include Scope 3 emissions but to also explore avenues beyond the act of reporting.

Srinivasan stated her belief that investments in sustainable technologies can mitigate the risks associated with technological change, thereby encouraging firms to adopt sustainable practices. Srinivasan went on to say that, as Darnall previously mentioned, it is essential to carefully assess both the actual outcomes as well as the ways firms utilize such investments. Nevertheless, de-risking technology change, she added, holds significant value for many firms, especially considering their substantial capital investments.

Lyon noted results of his research showing that financial incentives play a significant role in emissions reduction. With the seemingly considerable impact of the Inflation Reduction Act, low-cost finance can also serve as a form of financial incentive, he said. The results of his research indicate that investments in electrification or associated processes could benefit from such incentives.

___________________

30 More information about the U.S. Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program is available at https://www.epa.gov/ghgreporting

31 Dowell, G., & Lyon, T. P. (2024). Price, policies, and politics: The institutional drivers of greenhouse gas emissions (Working Paper). University of Michigan.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR CARBON PRICING TO ADDRESS DISTRIBUTIONAL IMPACTS

Noting the importance of distributional effects, Singh asked if there might be a method to tailor carbon pricing to address distributional impacts. He noted economic literature suggesting that, for example, carbon prices could be less expensive in developing nations. Could carbon pricing be utilized to enhance equity across countries and regions?

Lyon described the Citizens’ Climate Lobby, an organization that advocates for a fee and dividend system in which carbon pricing revenue is redistributed to households on a per capita basis.32 The aim, he said, is to provide greater relief to low-income individuals whose energy consumption tends to be lower, thus offsetting the impact of carbon pricing. Despite its potential for environmental justice impacts, he added, some environmental justice groups are hesitant about this approach because they prefer more comprehensive solutions that address the entire carbon state. Overall, while carbon pricing could aid in environmental justice efforts, opinions differ on its effectiveness and scope.

EXPLORING ENVIRONMENTAL, SOCIAL, AND GOVERNANCE INTEGRATION INTO DECARBONIZATION STRATEGIES

Commenting on the importance of environmental justice in the context of ESG considerations, as highlighted by the preceding panels, Planning Committee Member Aseem Prakash noted the significance of stakeholder reactions to new and existing projects. He was interested in understanding the extent to which ESG, particularly the social aspect, is integrated into discussions surrounding decarbonization strategies, corporate goals, and stakeholder engagement practices. He questioned whether mere “lip service” is being paid to ESG considerations—with a predominant focus on environmental concerns—or if there is a genuine corporate commitment to ESG principles.

In Darnall’s exploration of this space, she noticed a difference in the seriousness with which firms in the Global South, compared to those in the Global North, engage with the social aspect of ESG. While environmental concerns are often prioritized due to easier management from a regulatory standpoint, addressing social aspects—especially within supply chains—presents complex challenges. Her conversations with firms and governments revealed uncertainty about how to effectively manage social aspects, leading to a reliance on third-party organizations for guidance. However, she observed that even experienced third-party organizations acknowledge the difficulty of accurately measuring social impacts across supply chains. She suggested that this is an opportunity for robust social science research to both identify barriers to effective metrics and facilitate meaningful impact.

Largely agreeing with Darnall’s points, Lyon said that, in his discussions primarily with U.S. companies he found that although many prioritize both climate action and social justice, they often struggle with defining and implementing justice, grappling with questions like how to measure justice and which criteria are most important. The currently contentious atmosphere in the United States, he observed, has intensified this struggle. Companies feel stuck amidst polarized politics, he added, with corporate interests facing pushback from state attorneys general and others, further complicating progress.

With respect to the social aspect of ESG, Srinivasan said that industrial firms, particularly heavy industry, often focus on addressing workforce issues and workforce development, which can be seen as self-serving since ensuring a skilled workforce ultimately benefits the company. She noted that, historically, less effort has been directed towards addressing other social elements—such as diversity and inclusion—unless industry is prompted by litigation. The introduction of initiatives such as the Inflation Reduction Act and Justice4033 has brought social elements to the forefront of discussions and proposals. Although some companies may still offer only superficial support to these issues, she has observed that many are now compelled to deeply consider and define CBPs. She added that some firms, however, have refrained from applying for funding opportunities that require a CBP due to the depth of consideration and action doing so would entail. She concluded by saying that overall, while workforce issues remain an ongoing focus, firms are increasingly recognizing the need to address broader social concerns.

___________________

32 More information about Citizens’ Climate Lobby is available at https://citizensclimatelobby.org/

33 More information about Justice40 is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40/

Prakash suggested that the governance aspect—the “G” in ESG—is a crucial but often overlooked component in climate discussions. A notable lack of attention has been given to governance reforms and their ability to systematically reshape the nature of firms. He noted that, while some companies have made superficial efforts, such as appointing a chief sustainability officer or responding to shareholder resolutions, there is a need to elevate the importance of governance in the drive for meaningful change. By neglecting governance, he emphasized, a key factor that could significantly influence both environmental and social outcomes may be overlooked. He emphasized that to effectively advance the social science agenda, it is essential to prioritize governance reforms in all climate-related discussions.

Darnall suggested that the governance aspect may not capture as much attention as environmental and social metrics because it is less tangible and exciting. However, governance can serve as the foundation for the success of both environmental and social initiatives. More research and evidence are needed, she continued, to emphasize the significance of governance in driving organizational change. By highlighting the importance of governance reforms, Darnall said organizations can better prioritize their decarbonization efforts—and, by so doing, integrate the “G” into their decision-making processes.

EXPLORING THE INFLUENCE OF ORGANIZATIONAL ATTITUDES AND DEMOGRAPHICS ON CLIMATE ACTION AND SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES

Referencing Srinivasan’s point regarding the importance of company and management attitudes in driving climate action and sustainability initiatives, Singh asked if evidence exists—either from the medical field or from observing the participation of younger individuals in management positions—indicating whether this demographic shift within organizations leads to increased climate or sustainability action.

Srinivasan noted that while her research has not specifically examined the impact of age groups on the pursuit of climate action or sustainability initiatives within organizations, she has observed that firms that prioritize innovation have research staff with an innovation mindset who tend to foster openness and thought leadership. These firms can often make compelling business cases to management, which can, in turn, drive action on climate and sustainability. She observed that organizational culture and prioritization of innovation play significant roles in influencing climate action efforts.

Lyon noted his involvement with research that did not focus specifically on age but did explore various factors impacting greenhouse gas emissions reductions within corporations. One significant aspect was the influence of corporate structure and attitudes at both headquarters and individual facilities. Referencing data from a Harvard study on climate attitudes34 that measures beliefs about the reality and urgency of climate change, he said data point to a correlation between strong local beliefs and greater emissions reductions at individual facilities. This trend held true for attitude changes at both the headquarters and local levels. Interestingly, while both levels of attitude change were impactful, he observed that corporate level changes seemed to have a greater effect compared to local level changes. Moreover, he observed that corporate versus local levels of change substituted for one another rather than reinforcing each other, indicating the importance of addressing attitudes at both organizational and local levels.

EXPLORING SCOPE 3 EMISSIONS DISCLOSURES AND ENGAGING YOUNG TALENT IN SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES

Panelist Edson Severnini (see Chapter 4) asked about disclosure practices regarding Scope 3 emissions and whether examples of research or success stories exist where companies effectively reported all Scope 3 emissions. He also asked about social or environmental justice implications in this context.

Although she had no specific examples, Darnall noted that when considering procurement emissions—which fall largely under Scope 3 emissions—companies are compelled to delve into the communities from which raw materials are sourced. She suggested that this requires a collective approach to understanding impacts beyond

___________________

34 Decheleprȇtre, A., Fabre, A., Kruse, T., Planterose, B., Chico, A. S., & Stantcheva, S. (2023). Fighting climate change: International attitudes toward climate policies (NBER Working Paper No. 30265). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30265

workforce issues, encompassing concerns such as modern slavery and fair wages in the communities where operations occur. These layers of justice issues, she added, are often overlooked in discussions centered on Scope 1 and 2 emissions—meaning that grappling with Scope 3 emissions could generate significant spillover benefits.

She observed that younger individuals are inherently more receptive to sustainability initiatives compared to older generations, meaning that “selling” sustainability to younger people does not require the same level of persuasion as it does with older individuals. In her experience working with federal-level stakeholders focused on sustainable procurement, she noted increasing interest in adapting recruitment strategies to appeal to the values of the younger workforce. She further noted that this demographic seeks to make a meaningful impact through their work. The field of sustainability presents a unique opportunity to attract and engage young talent in ways that were previously infeasible.

Reflecting on Srinivasan’s insights on organizational culture and discretion, Darnall emphasized that leaders play a crucial role in setting the tone within their organizations, and when leaders empower individuals to experiment and learn from mistakes, these practices foster a culture of innovation and progress. Such a culture allows new ideas related to decarbonization to flourish and gain momentum, she said, leading to meaningful advancements in sustainability efforts. Singh commented that he has observed a trend in which younger people with Ph.D. degrees are increasingly opting for sustainability roles in industry over traditional academic positions.

Confirming Darnall’s observations, Lyon pointed to his experience in the classroom, noting that undergraduates clearly express support and readiness for sustainability initiatives. He emphasized that, as a result, companies may need to cater to a workforce comprised of both enthusiastic younger individuals as well as older employees who may not share the same level of excitement for sustainability initiatives, which may prove challenging.

BROADENING EXPECTATIONS, UNDERSTANDING MARKET ADOPTION, AND ADVOCATING FOR RESPONSIBLE ACTION

Emphasizing the intricate landscape in which social scientists operate, Darnall underscored the need to avoid overlooking critical aspects of the supply chain. She said that while it is tempting to concentrate solely on the firm, “it is essential that we begin to push our expectations much further than those boundaries if we are serious about decarbonization.”

Srinivasan concluded by highlighting the significance of social and behavioral factors when it comes to influencing market adoption. Even if a technology is innovative and economically viable, she suggested, its acceptance by users can be hindered by these factors. She said she appreciates the panel’s focus on this crucial area and is eager to see what results.

Referencing Srinivasan’s point that beliefs significantly influence actions, Lyon said that while he finds it disheartening that that some companies seek to undermine climate science, he believes it is crucial for more companies to support scientific findings and advocate for responsible political action. Based on his observations, research underscores the ability of states to still achieve substantial progress despite federal limitations due to polarization, and, for this reason, states deserve greater focus and attention.