Exploring the Ecosystem of Health Equity Measures: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2024)

Chapter: Exploring the Ecosystem of Health Equity Measures: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

Exploring the Ecosystem of Health Equity Measures

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

On June 21, 2023, the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement and the Roundtable for the Promotion of Health Equity held a workshop on the Ecosystem of Health Equity Measures in Oakland, California. The co-chair of the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement, Ana Diez Roux of Drexel University, made opening remarks reflecting on the roundtable’s past exploration of measures (or metrics1) of health disparity and health equity that considered how these measures can be used to enhance understanding and awareness, and to promote and support action. She noted that measures reflect values, and they can be used to both illuminate and mask reality, thus warranting discussion and debate.

Planning committee chair Sheri Johnson of the University of Wisconsin, Madison gave an overview of the workshop objectives and the agenda. The evolving ecosystem of health equity measures, she stated, includes scientists, practitioners, and people with “firsthand knowledge of systems and structures that produce inequity.” She added that collaboration and alignment are needed to decide what new measures are needed, what measures should be retired, and what measures matter. Though not offering a comprehensive examination of the ecosystem of measures, the workshop was intended to:

- Critique concepts, language, narratives, and framing of measurement of health equity;

- Examine the nature and purpose of metrics for transformational change;

- Discuss the state of the science and the social and political implications of designing data collection and methods; and

- Explore measures at different scales and in different domains.

Johnson asserted that achieving health equity requires researchers to examine their own biases, and ask: Who can gather the data and construct the measures?; Who owns the data and the measures?; What is the right balance of measuring problems versus solutions; and Whose problems are being named?

DEFINING HEALTH EQUITY

Paula Braveman of the University of California, San Francisco titled her presentation “To Measure Health Equity, We Need to Know What It Is.” She underscored that the journey to achieve health equity is long, and those undertaking it may get lost along the way, in spite of

__________________

1 Metrics that Matter for Population Health Action: Workshop Summary. See https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/21899/metrics-that-matter-for-population-health-action-workshop-summary.

![]()

their best intentions. She shared common pitfalls when defining health equity:

- The definition guides measurement.

- Social justice content becomes lost or buried.

- Definitions that are too ambiguous to guide policies or set priorities.

- Reliance on causal inferences that may be difficult to support with evidence.

- Definitions that lack a firm conceptual or technical basis or that are too technical, complex, or rhetorical to appeal to a wide audience.

Braveman provided several definitions of health equity and related terms and outlined their strengths and weaknesses. British public health researcher Margaret Whitehead defined health inequities as “differences in health that were not only avoidable and unnecessary, but also unfair and unjust.” Despite that definition’s power and usefulness, Braveman said, its terms—fairness, justice, and avoidable—are subjective, and it also does not guide measurement. Health equity is often defined indirectly by reference to health disparities, a concept Braveman said she considers “an indispensable tool for measuring progress towards health equity.”

Early definitions of health disparities by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and others were informed by basic epidemiology as “differences in the prevalence, incidence, or severity of diseases among different populations.” Braveman said that such definitions do not reflect social justice, and they limit the comparisons to differentials in power, wealth, and privilege. Health disparities could be defined as health differences that are caused by social injustice—an intuitive and clear definition, but one that does not reflect a causal link between a social disadvantage and a health outcome.

Braveman outlined “three levels of jargon”: (1) differences or variations in health status or outcomes; (2) disparities or inequalities, which are differences associated with social disadvantage and advantage, and (3) inequities—disparities that are unfair or unjust. She then shared a widely embraced definition of health equity:2

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care. For the purposes of measurement, health equity means reducing and ultimately eliminating disparities in health and its determinants that adversely affect excluded or marginalized groups. (RWJF, 2017)

This definition is intuitive, clear about its values, and, Braveman emphasized, consistent with human rights principles, such as nondiscrimination, the obligation to remove avoidable obstacles to health, and the interconnectedness of rights—to education, health care, and civil rights. But the definition is too long, with many using only the first part, and its measurement aspect is somewhat technical. In closing, Braveman said that the pursuit of health equity requires measuring progress such as comparing haves and have-nots, and that can be uncomfortable but is unavoidable.

The next speaker, Andrew Anderson of Tulane University, outlined methodological considerations in measuring health equity, beginning with the basic components of a health equity measure:

- An indicator of health or modifiable determinant of health (e.g., incidence of disease, disability, mortality, risk);

- An indicator of social position, or a way of categorizing people into different groups or strata (e.g., neighborhood, diet, power relations, skin color); and

- Methods for comparison between those groups, which include defining the group, defining a reference group (e.g., comparing the Black population to the White population), absolute versus relative terms, and valuing health improvements differentially along the distribution.

Regarding the choice of groupings, Anderson listed several approaches, including selecting a reference group deemed to be advantaged a priori; a minimum below which health performance (e.g., premature death, pre-

__________________

2 Braveman, P., E. Arkin, T. Orleans, D. Proctor, and A. Plough. 2017. What Is Health Equity? And What Difference Does a Definition Make? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. May. https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html (accessed July 30, 2024).

![]()

ventable hospitalization) is considered inequitable; the reference group value at the mean of all groups; or the group with the highest observable health status. These approaches offer choices that may lead to different outcomes.

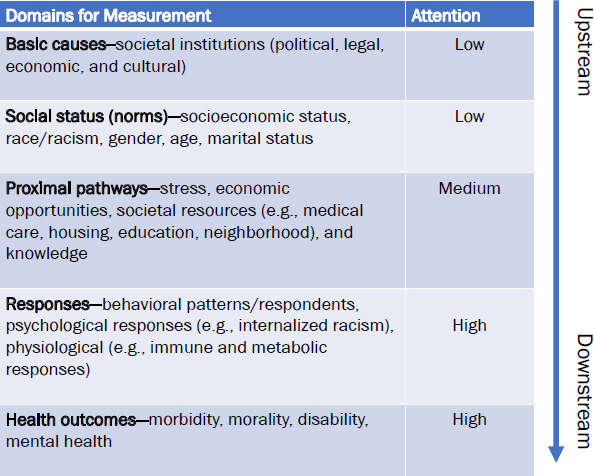

Anderson shared a reformulated version of David Williams’ framework for studying racism in health, where the upstream domains for measurement (i.e., basic causes) get less attention, meaning fewer measures are available; the proximal pathways or mediators get some attention/measures; and the downstream domains, such as health outcomes, get more attention, meaning more measures, often because they are easier to measure (Figure 1).

Anderson concluded with three key takeaways:

- The choice of health measure—the groupings, the reference groups, and the type of measures used—all have important implications for understanding health disparities and health inequities.

- These complex domains and issues require multiple measurement approaches.

- There have been recent advances in both attention to and funding of measurements of structural racism.3

SOURCE: Anderson presentation, June 21, 2023.

THE STATE OF THE SCIENCE ON METRICS AND DATA SOURCES

Fernando De Maio of DePaul University and the American Medical Association said that P values and data are important to policy, but consideration of the social and political context may be similarly important. De Maio said that data themselves may be flawed, as underscored by the “Major Gaps in the Data” warning on the Satcher Health Leadership Institute Health Equity Tracker web page,4 and analyses may cause or perpetuate harm. He said, “Structural racism not only generates unequal outcomes and unjust outcomes, it also permeates and is embedded within our data systems.” The COVID-19 pandemic, he added, showed how missing data could be perpetuated “by what we incentivize and what we deem worthy to collect.” He shared Abigail Echo-Hawk’s charge of Data Genocide of the American Indians and Alaska Natives in COVID-19 Data5 as an example. He paraphrased Nancy Krieger’s assertion that data is a two-edged sword: (1) “no data, no problem” where the absence of data helps deflect responsibility or hides injustice and (2) “problematic data, even bigger problems” where data is poor, or misused, and causes harm. Data is a matter of life and death, DeMaio said, before introducing the panelists.

Amy Branum of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) gave an overview of the agency’s major data systems, including the National Vital Statistics System, three major household interview surveys (National Health Interview Survey, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES], and the National Survey of Family Growth), and a suite of surveys related to health care. Branum noted that historically, NCHS has documented health differences, but it is increasingly prioritizing the measurement of health disparity and health equity as evident by the focus of the most recent Health, United States, 2020–2021 report. As an example, Branum shared how equity indicators from the HOPE Initiative6 are gathered from NCHS data and presented some challenges that characterize the data.

- Household surveys are intended to be nationally representative, but that makes it difficult to include all subpopulations of interest.

__________________

3 See for example https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR23-112.html and https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1069476/full (accessed July 5, 2024).

4 https://healthequitytracker.org/exploredata (accessed May 7, 2024).

5 https://www.uihi.org/projects/data-genocide-of-american-indians-and-alaska-natives-in-covid-19-data/ (accessed May 7, 2024).

6 https://www.hopeinitiative.org/ (accessed May 7, 2024).

![]()

- Some survey content lacks continuity due to fluctuations in sponsorship.

- NCHS is dependent on the vital statistics that states, territories, and the District of Columbia, are willing to provide under their cooperative agreements with the agency.

- There are challenges with statistical reliability and the disclosure risk of small subgroups, as well as discontinuity over time (e.g., race/ethnicity standards).

To illustrate her first point, she stated that NCHS receives questions about lack of data on American Indian or Native Hawaiian populations, and she explained how addressing this need through oversampling has ramifications for the sample, requiring a careful balance. NHANES only goes to 15 counties per year, so one solution to improve representativeness is targeted surveys. For example, a Hispanic HANES, and a Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey have been used, but these are resource intensive, because such targeted surveys are conducted in addition to the main surveys.

NCHS has been increasing its focus on what Branum called “nontraditional measures,” including those related to the social determinants of health, such as the National Health Interview Survey’s new measures of social support and life satisfaction, added in 2021. Branum then described the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) race and ethnicity revisions. This change, she noted, is informed by the increase in both decennial census and the American Community Survey of “Some Other Race” responses to address inconsistent and outdated terminology and the need for more detailed group collection. She added that the Federal Register Notice from OMB outlined the proposals for the revised standards from the currently separate yes/no question on Hispanic ethnicity, to a proposed new question with seven categories, including the Hispanic or Latino ethnicity selection.7

NCHS has been using more data from electronic health records (EHRs), but a key flaw is the quality of data on race and ethnicity. Other flaws include data variability across systems, and OMB standards do not apply to EHR data. Branum concluded with a list of resources from NCHS.

Carolyn Liebler from the University of Minnesota noted that race and data about race are socially constructed, meaning that human choices, power, and politics determine which race groups are coded, included, and differentiated during analysis. Liebler outlined four main points:

- Individuals change their race and ethnicity responses from one survey to the next for many reasons. A solution is to use linked data to understand changes over time.

- Federal definitions of race and ethnicity categories change. They were first defined in 1977 to help enforce civil rights laws. The current standards date to 1997.

- The 2020 U.S. Census changed its race and ethnicity data coding. Race bridging is a method used to make different data collection systems sufficiently comparable to analyze race-specific statistics. Liebler developed predictive models to estimate “which single race group a multiple race person will choose depending on their personal characteristics, age, sex, and local context.”

- To protect the 2020 Census, the Census Bureau is applying a differential privacy algorithm that adds or subtracts a random number to a smaller population. This can cause misreporting and overestimation of values. Such changes to the data can limit their usefulness.

Liebler called on the field to ask: “Who is socially constructing these things, and how can we shift that to relieve some of the inequities that are being introduced?” and to reflect on how true equity would look.

Sam Harper of McGill University spoke about the need to move from describing inequalities, to explaining them to inform interventions to change them. Harper provided examples for how health inequalities can be examined and illustrated how analytical tools can be used to help evaluate potential explanations for inequalities. It is most complex to understand health inequities that result from

__________________

![]()

multiple intersecting identities and interlocking systems of power and oppression—and often studies analyze these complex issues by single axes (e.g., gender, age, socioeconomic position), which overlook joint effects and rely on inadequate data systems. Work from Evans and colleagues demonstrates multilevel analysis of individual heterogeneity and discriminatory accuracy, to reveal multidimensional heterogeneity.

Harper discussed Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism by Anne Case and Angus Deaton—a compelling narrative based on the authors’ analysis of mortality data and their emphasis on “the simultaneous rise of drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related deaths” in the White population. Case and Deaton traced the decline in life expectancy in less educated, middle-aged, White men to declining economic opportunities. Harper noted that this “empathetic narrative was mostly absent during prior epidemics that affected mostly non-White, rural populations.” Harper and colleagues used analytic methods to decompose8 the decline in life expectancy between 2014 and 2017 and examine heterogeneity by race/ethnicity, gender, and cause of death.9 They found data hard to reconcile with the deaths-of-despair narrative and their findings underscore the value of challenging outdated and incomplete narratives. Findings included: the highest burden of disease was in urban areas; non-Hispanic Black men had the largest decline in life expectancy, of nearly 0.7 years (nearly twice the decline in White men); and opioid overdoses contributed to declining life expectancy for all race/ethnic groups. They also found that increases in homicide actually accounted for a larger share of the decline in Black men. Homicide, Harper noted, is “deeply connected to persistent and systemic racism in the United States,” and is largely overlooked in the deaths-of-despair narrative. Finally, suicide deaths made almost no contribution to the life expectancy decline for any group; and the decline in life expectancy for non-Hispanic Asian Pacific Islander women was nearly the same as that in White women, although not because of opioid overdoses. Harper added that Black, American Indian, and Alaska Native populations currently experience the greatest burden of opioid overdoses.

Harper said that researchers have the tools and new data to provide better explanatory evidence on health inequalities and their evolution over time; those data provide opportunities to reconcile and integrate empirical evidence with dominant narratives that “often minimize alternative explanations and solutions.”

Q&A and Discussion

Mohamed Jalloh of Partnership Health Plan of California asked how organizations could choose when to use absolute versus relative measures of inequities. Anderson recommended using both or explaining why one was used and not the other, and Braveman agreed. Julia Kaufman of the RAND Corporation asked about strategies for obtaining state data. Branum answered that the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the difficulty getting good state data and underscored that this is a challenge across the federal government, which came under criticism for lack of transparency or actionable data.

Michael Samuel, California Department of Public Health, asked Liebler when new Census data are appropriate to use (given, for example, the differential privacy “error” added to the data). Liebler encouraged data users to look at the demonstration data and gauge the level of variation.

DeMaio was asked about the use of data to galvanize action, and he responded that although data are fundamental, they are not enough. He paraphrased Carles Muntaner, co-chair of the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, that it is unethical to continue describing health inequities over time without working for change. Rachel Harrington from the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) asked how the field can bring nuance back into the discussion about data and avoid the point estimates that assume that data is value-free. Harper acknowledged the pressure to prioritize point estimates, P values, and sampling error, and to ignore factors such as uncertainty. It is complex to communicate “systematic issues related to misclassification, or selection bias, or confounding,” and he underscored the responsibility of researchers “to be as trans-

__________________

8 See for example: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2735056 (accessed June 18, 2024).

9 Harper, S., C. A. Riddell, and N. B. King. 2021. Declining life expectancy in the United States: Missing the trees for the forest. Annu Rev Public Health 42 (Apr 1):381-403. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-082619-104231.

![]()

parent and [as] honest as we can about the uncertainty in our estimates.”

AN OVERVIEW OF HEALTH EQUITY MEASUREMENT EFFORTS IN HEALTH CARE AND HOSPITALS

Philip Alberti from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) asserted that to achieve health equity and to ensure authentic health opportunity so all communities thrive requires centering community wisdom and momentum, and coordinating and aligning multisector efforts that shift underlying structures and systems toward justice. Alberti said the session would focus on health care’s right-sized role and responsibility in achieving population and community health equity, emphasizing a need for the sector to acknowledge its role in medicalizing health equity work, and a lack of authentic patient and community engagement.

Harrington introduced NCQA’s mission to transform health care through quality measurement, transparency, and accountability. NCQA’s Health Equity Accreditation is a 3-year standards-based program focused on collecting data to understand needs (e.g., by race/ethnicity, language, sexual orientation/gender identity), and identifying and acting on opportunities to reduce disparities and improve cultural and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS). Going beyond CLAS, the accreditation process also asks about organizational readiness to further equity.

Health Equity Accreditation is being used by payers (states, Medicaid agencies, marketplace exchanges) and by policy makers mandating accreditation, while Health Equity Accreditation Plus offers another kind of opportunity for market differentiation and market competition. NCQA’s Health Equity Accreditation Plus builds on the core framework and focuses on the data on unmet social needs of a community and its members and what partnerships can respond to and improve those needs. Harrington added that if a health care organization is working with community-based organizations, they are also asked about the nature and power dynamics of the partnership, the programs being implemented by the partnership and its effects, as well as the flow and quality of the data used to inform the collaboration.

Measurement and accountability go together, Harrington said, and asked if the field is promoting inclusive approaches to measurement and accountability. Harrington described the Framework for Equity Measurement,10 which she said aims to address disparities and close gaps in access to care and health outcomes. Giving the example of cervical cancer, she noted that screening has historically been associated with the category of “women 45 and older.” The reality is that screening should not be associated with gender but with the existence of a cervix: “If you have a cervix, you need cervical cancer screening.” Quality measures need to be redefined so “anybody who needs that care gets that care, regardless of structures of the data and how we’ve defined that in the past.” Harrington also mentioned that health equity measures have been integrated into the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) health plan measures, including race and ethnicity stratification, sexual orientation and gender identity, and in 2024, disability. She added that there is growing attention to, and resources for, addressing social risks, calling for screening for and intervening in social needs.

Rukiya Curvey Johnson from Rush University Medical Center described key milestones in the academic medical center’s health equity journey, beginning with a 2016 community health needs assessment report that named structural racism, economic deprivation, and other social and structural determinants of health as among the root causes of the poor life expectancy of the West Side neighborhoods of Chicago. In 2017, Rush cofounded the Healthcare Anchor Network and codeveloped a playbook while launching West Side United along with other area hospitals. In 2021, the Rush BMO Institute for Health Equity was launched to coordinate, scale, and disseminate the health system’s work, including a systemwide health equity strategy.

Curvey Johnson acknowledged the rapid proliferation of measurement frameworks for equity, noting the variation in measures, domains, and methodologies, along with a lack of consistency and validation for some measures, and discussed the partnerships and efforts Rush is undertaking to address these issues in their work. Beyond data collection and measurement, she said, Rush works

__________________

10 https://www.ncqa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/NCQA-CHCF-EquityFrmwrkMedicaid-Sep22_FINAL.pdf (accessed May 13, 2024).

![]()

to further its anchor mission—its focus in investing in economic and human resources to respond to the social determinants of health—by attending to hiring, procurement, and other activities that have implications in the communities residing around the health system facilities. After highlighting investments in developing health care career pathways and supporting local small businesses in the community, Curvey Johnson spoke about the importance of quantifying investments in the community that are not typically represented in institutional reporting relevant to advancing health equity.

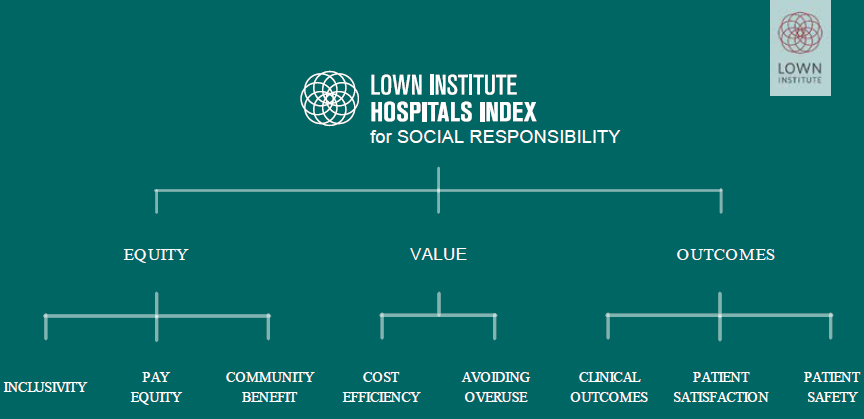

Vikas Saini of the Lown Institute shared that 1980 marked an inflection point in the relationship between life expectancy and health care expenditure. Despite developments in biomedical science, he noted, Americans experience worsening outcomes ranging from diminishing returns, to neglect of public health investments, to health care advances that are not improving outcomes. The Lown Institute Hospitals Social Responsibility Index was intended to reframe what it means to be a good hospital, beyond a ranking that marginally benefits the bottom line and with the aspiration that the goals of equity, quality outcomes (clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and patient safety), and value could be similarly motivating (Figure 2). He said that the hospitals index resides at the intersection of the Lown Institute’s three pillars of work: equity, value, and accountability.

Saini described the metrics in the equity domain of the index, the community benefit metric assesses the fair share deficit, noting that 77 percent of hospitals spend less on community benefit (i.e., financial assistance and community investment) than the estimated value of their tax breaks. The pay equity metric, Saini added, determines how fairly staff are paid compared to leadership. Finally, the inclusivity metric uses claims data to compare the demographics of the patient population to the demographics of the geographic area, demonstrating how well a hospital serves people of color, people with lower levels of education, and those with lower incomes.

Q&A and Discussion

Alberti asked Harrington to talk about the tension between market forces and “the spirit of health equity work, the spirit of community collaboration” and asked whether it is more helpful to measure an organization’s own progress over time or to compare its performance to peers. Harrington said that organizations are recognizing and addressing contextual factors through multiple lenses, including mission alignment, social responsibility, quality management, and business case. Curvey Johnson added that emergency department admissions can be an important metric to track the effectiveness of efforts to address other patient needs, such as transportation. Saini said that influences beyond market forces are necessary, including accountability to community. Hospital rankings, if used as a tool for market competition, do not work to further health equity, he added.

Roundtable co-chair Raymond Baxter asked about the tension between compliance with externally imposed

SOURCE: Saini presentation, June 21, 2023.

![]()

requirements and the embrace of internally mission-driven and community-responsive measures. Curvey Johnson responded that it is possible, though challenging, to respond to both imperatives—and noted that Rush’s long engagement in the Healthcare Anchor Network, along with the commitment of its leaders, helps. Harrington added that health care institutions are mission driven, but there are financial and business drivers to examine, too. How is equity integrated in how bonuses are calculated, in organizational expectations, and in how advisory boards are engaged in decision making? Where does change come from, Harrington asked, and what modes of leadership are effective in driving it? Saini added that external influence is important, but it will not foster a culture of change.

Lisa Meritt of the Multicultural Health Institute asked how hospitals can work with community health workers (CHWs), who tend to be culturally representative and competent, in historically marginalized communities. Curvey Johnson described the relationship between Rush and the community health workforce, who are viewed as trusted messengers and shape the research agenda. Saini added that the power pyramid needs to be inverted for a workforce that is neighborhood based—with community health workers and community nurses—to increase the focus on neighborhood primary care. Saini also suggested “forc[ing] the conversation in the direction of the health needs of a community, not the business strategy of a given hospital.” Adequately supporting implementation efforts could increase community participation and facilitate conversations about power and decision making, as well as ways to track those dimensions over time.

Alberti emphasized the value of, and the need for, health system payment for community-based practitioners and highlighted AAMC’s principles of trustworthiness that outline how organizations can demonstrate they are worthy of community trust.

Gary Gunderson of Wake Forest University said that community benefit measures can be deceptive because federal law does not require organizations to disclose their investments and asked Saini if Lown Institute has engaged credit rating agencies about integrating equity. Saini said investment decisions are multidimensional and can controversial, such as the current debate over environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations. Hospital bond markets are linked with the S (social responsibility) in ESG, he acknowledged, and there could be value to including hospital social responsibility in bond ratings.

In response to a participant’s question about addressing racism through health system investments, Curvey Johnson shared that Rush works with the local school system to provide early enrichment across the educational continuum. Rush also has work-based programs that target underrepresented minority groups to engage them in pathways to jobs in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and health care. Other Rush efforts include developing a wellness village in West Garfield Park that will bring in community amenities such as a YMCA, a federally qualified health center, a grocery store, and a credit union.

Alberti asked Harrington and Saini about the role of community in governance from an accreditation and ratings standpoint. Harrington said that NCQA’s Health Equity Accreditation Plus includes a focus on health care partnerships with community-based organizations. Saini said that more work is needed to understand how to measure community governance.

Alberti asked what revisions to Schedule H of Form 990 are needed to incentivize and hold tax-exempt health care entities “accountable for community health improvement, population health, and health equity.” Curvey Johnson mentioned the difficulty of capturing types of investments over time, while Saini noted a need to examine the relationship between community health needs assessments and community health spending. Harrington said, “Rethink who defines what matters… then who is defining what matters, and who is defining which measures get prioritized.”

COMMUNITIES AS COCREATORS OF MEASURES AND DATA, AND AS DRIVERS OF THE MEASUREMENT AGENDA

Hanh Cao Yu of The California Endowment reflected on previous sessions about the what of health equity measurement and said that the panel to follow would focus on the how.

Ryan Petteway of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland State University School of Public Health, began by discussing the theory and power behind measurement.

![]()

“Do we really think that the reason we still have to deal with structural racism is because we haven’t measured something well enough?” he asked. Petteway acknowledged that public health training is focused on deficits and narratives of damage which trains people to “reproduce settler colonial extractive white supremacist logics” in assessing and addressing community health. Who is producing knowledge about whom, he asked, as he outlined the four domains of power: structural, disciplinary, hegemonic, and interpersonal (Hill Collins, 1991).11 While defining and illustrating the meaning of disciplinary power and hegemonic power, Petteway reflected on how CDC uses the word surveillance in the nation’s most prominent public health survey, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. He said:

If we’re not thinking about these things when we download from the Internet [a] dataset that cost $30,000 about a community 3,000 miles away that we never stepped foot in, and we pump out our odds ratio and we say that this community is worse off, then what are we doing with that narrative? Is that narrative actually going to help transform what is going on in that community and produce action?

Petteway repeated: Who is producing this knowledge? Less than 6 percent of tenure-track faculty are Black, less than 6 percent are Latinx, and 0.3 percent are Indigenous—who is telling whose story? What about the composition of editorial boards, NIH grant review boards, he added. “These are conversations that are not happening in the public health discourse.” He listed the ways in which public health research funding is spent and asked whether those expenditures are furthering health equity, rather than simply furthering academic interests.

Petteway said that in his work as an applied scholar, community-based participatory researcher, and youth participatory action researcher, he tries to integrate various fields, theories, and frameworks to conduct “people-powered social epidemiology from the ground up.” He called on the field to reimagine community-based research by paying community members to do the work that is important to them.

Somava Saha of Well-Being and Equity in the World, and the Well-Being in the Nation (WIN) Network, introduced the WIN measures as a collaborative approach to defining, measuring, and improving what matters to communities. The 2019 Measures That Matter to Communities identified data at a sufficiently local level, and tools to measure the things that were important to communities. The starting point for this work was “understanding what it means to not merely survive, but to thrive, to see communities as asset rich and as communities of solution, and to begin to understand both what was missing that had been extracted, but also what was possible that could be built upon,” said Saha.

The WIN process uses storytelling and dialogue, integrating the work of people of color, uses meaningful language, and explores how measures of equity, and structural and system change can be used for accountability. The WIN work on measures grew slowly, building on earlier efforts, and led to an evolving library of measures. The most current iteration uses the Vital Conditions framework that centers belonging and civic muscle and considers structural racism as a factor that shapes well-being.

Saha concluded by asking, “What are the tools that we can create together in a living democracy that are about how we change our world, how we understand our world, how we build on assets, and how we create the conditions for us to build an equitable, thriving democracy in which everyone’s contribution can matter?”

Paul Speer of Vanderbilt University outlined four key points:

- The magnitude of the problem is underappreciated; there is investment in improving equity, but it is far overshadowed by what is spent in other domains (e.g., sweetened beverage marketing).

- Progress toward health equity requires the development and exercise of social power.

- Health equity will be improved only if power exercised results in positive community change.

- Metrics for health equity are needed so change can be measured.

__________________

11 Hill Collins, P. H. 2008. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge.

![]()

On the subject of change, Speer described symbolic change (no tangible change), incremental change (i.e., tangible change, but the gap between haves and have-nots remains the same), and restructuring—the kind of change that characterizes health equity work. In restructuring, “the share of a valued resource gets distributed much more equally.” Speer then spoke about how measurements of communities are not merely about high school graduation rates, or demographics, but about dynamic processes, including community change.

Q&A and Discussion

Yu asked Speer how a community can be involved in measuring power. Speer shared his work with a community organizing group in New Jersey, to analyze data they had gathered on violent crime and used it to change policy that ultimately led to lower rates of community violence. Petteway said that because he solely uses participatory methods, he sees himself as a facilitator and not an extractor of data and mentioned such tools as participatory geographic information systems, Photo-Voice, and participatory photo mapping. Petteway critiqued traditional survey methods that gather large data sets and cannot turn those data into action. Researchers, he added, also need to think about how to build power with and train the community (like organizers do) to conduct research to effect local change.

Yu asked Saha to talk about how WIN thinks about data governance and sovereignty in the process of building power. Saha mentioned stewardship councils and rounds of meetings to inform collective decision making about data and the use of resources. As a result of these processes, community organizers were able to show policy makers the linkages between health outcomes and food, housing, and financial insecurity, as well as to shift investments in farming supports, broadband, and other community-identified priorities.

Jason Purnell of the James S. McDonnell Foundation asked how the field could engage in restructuring change. To illustrate the magnitude of change, Speer shared that a city can invest X dollars to create Y affordable housing units, but at that rate of change, it will take 135 years to achieve restructuring change. Saha said that the WIN work is about “mapping solutions, assets, power, and influence all across the ecosystem” and developing “a clear understanding of the legacies, structures, and systems that are operating and how we collectively shift our practice, so we don’t replicate the usual exercise of power in the process of changing the system.” Petteway spoke about how academic institutions get million-dollar grants with no accountability. For example, universities conduct studies over many years with no improved outcomes. Recipients of grants need to show how they can turn research funding and knowledge “into tangible, measurable, actionable change.” Petteway spoke about ways to reimagine the research, such as working with community researchers to collect fresh data instead of working through academic researchers using outdated figures. Yu shared that The California Endowment’s decade-long Building Healthy Communities initiative led to 1,700 policy, systems, and physical changes, but communities also critiqued what they saw as short-term wins and led the foundation to invest in infrastructure building and strengthening networks and ecosystems for change.

An online participant asked for tips for health care leaders who are burning out in the field of health equity. Petteway said that the field needs “more of us, and we need to…improve our training so we can be a better version of ourselves.”

An audience member asked for advice for community members with disabilities—especially those who may also be a person of color or LGBTQ+—to advocate for their value, time, and energy, with the health care practitioners and researchers who ask them for their data. Saha and Speer both responded that all expertise should be paid. Speer added that it is helpful when people can come together collectively in interacting with researchers.

Gunderson asked how the nation’s data system can be transformed to one that centers communities by supporting more data collection and research that can inform local policy making. Saha noted the growth in development of data collection at the community level, and greater attention at the federal level, to measures of local interest, such as voting, well-being, and loneliness. She said that WIN’s approach brings people in proximity to each other, to implement shared governance of processes, and expand access to processes that shape the data being gathered by the current system. Change will require building community infrastructure for gover-

![]()

nance and directing resources to communities to support research and collecting information important to them—not only data, but also stories and other kinds of community knowledge, she said. Petteway agreed that “[s]tatistics are not what people vote on. People don’t go to the ballot box because of an odds ratio change to their lives [has] inspired them.…[T]he real key is to allow folks to be engaged in that data process and storytelling process as an act of political engagement, as an act of civic engagement.”

MULTISECTOR MEASURES/INTEGRATING DATA AND MEASURES FROM NONHEALTH SECTORS

Rachel Thornton of Nemours Children’s Health said that health is “an endpoint of many pathways linked with income, wealth, economic stability, with affordable and safe housing, and thriving communities, with educational equity, good jobs, economic development, and opportunities for civic engagement” and thus it is necessary to consider measures from domains beyond health.

Erin McDonald of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health shared the work of the federal interagency group that produced the Federal Plan for Equitable, Long-Term Recovery, and Resilience (ELTRR). That process began at the height of the pandemic, and more recently has been furthered by executive orders, and presidential memos, and has aligned collaborative efforts across 45 departments and agencies that coauthored the federal plan. That diverse federal partnership is oriented toward the vital conditions for health and well-being—an asset-oriented framework focused on the social determinants of health. The federal effort includes asset mapping that is both place-based (local) and network-based and has data and measurement components.

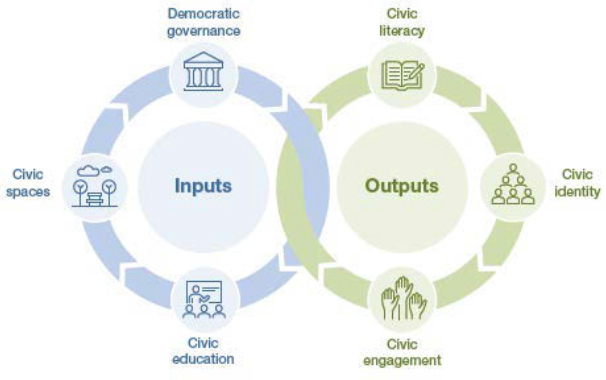

Kaufman shared her research on defining and measuring civic infrastructure. She noted that the recognition of the relationship between community health and civic infrastructure dates back decades. For example, John Parr—who led the National Civic League, talked about civic infrastructure in 1993 as “the individual structures and processes through which communities solve problems [and] make decisions.”

She offered a framework to illustrate the relationship between civic education (input) and civic engagement (outputs) (Figure 3).

SOURCE: Kaufman presentation, June 21, 2023.

She quoted Daniel Dawes’s remarks at the roundtable’s 2021 workshop on civic infrastructure: “For every social determinant of health…there was a preceding legal, regulatory, ordinance, legislative, or other policy decision.”12 Speaking about why better measures for civic infrastructure are needed, Kaufman said that the body of work on democratic governance primarily focuses on nations, not on U.S. states. The body of work on democratic governance primarily focuses on nations, not on U.S. states. Her own research on civic infrastructure has pointed to widening differences from state to state in voting rights, in the rights of LGBTQ+ people, and in the ability of teachers to speak on certain topics; additionally, there are data on voting, but not on other types of civic engagement. Across states, there are also considerable differences in academic standards pertaining to civics learning. For example, the only systematic outcomes data on civics achievement is from the National Assessment of Education Progress, which measures eighth graders’ civic knowledge, she noted. States would benefit from federal government support to identify a wider set of measures to capture civic engagement and civic infrastructure, and collaborating with communities could help.

Adria Crutchfield of the Baltimore Regional Housing Partnership shared the organization’s mission to expand “housing choices for low-income families, helping them to access vibrant communities.” The partnership pairs housing choice vouchers with housing counseling services and works with over 4,300 families, primarily those

__________________

12 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2023. Civic Engagement and Civic Infrastructure: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington DC: National Academies Press. P. 6.

![]()

with children, that are enrolled in the federally funded voucher program. This enables 2.2 million households to close the gap between 30 percent of the renters’ adjusted gross monthly income and the market rate rent.

Crutchfield referred to work from economist Raj Chetty revisiting the Moving to Opportunity program data that indicates income gains in participating children, and that taxes on those gains cover the voucher program costs. The program utilization rate in her program is 97 percent, with considerable stability (less moving from unit to unit), 67 percent of the people served by the partnership reside in opportunity areas, and more than half of families are employed or recently employed. Crutchfield added that the Partnership’s Healthy Children Voucher Demonstration supports 150 families in public housing who could benefit from moving to a new neighborhood for health or developmental reasons by pairing housing counseling with vouchers or rental assistance. The organization plans to partner with the local health department and others to track health outcomes data.

Q&A and Discussion

Thornton asked Crutchfield to describe the counseling services her organization offers. Crutchfield said that “pre-move services” include workshops; support for a housing search; referrals; and in-person tours with highlights of schools, transit, and other community amenities. Post-move services include 2 years of follow-up home visits, counseling, and other resources.

Thornton then asked each speaker to reflect on the measurement of health equity in their respective domain. Kaufman spoke about work in the education sector, including collaborating with the Council of Chief State School Officers to equip teachers with better instructional materials, gathering data from, and then sharing back to teachers and school leaders. McDonald spoke about the multisector aspect of the federal interagency plan and the stage it has set for collaborative action, and she underscored the value that public health and health equity data can give leaders and agencies from other sectors. Crutchfield reiterated Chetty’s work, which has increased interest in reevaluating how the housing choice voucher program is administered. She also mentioned a randomized, controlled study in Seattle-King County, Washington, which led to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Mobility Demonstration. She said her organization’s partnership with health care is exploring how providers can write a prescription for housing and how eligible families who get access to housing in a better neighborhood could experience improved health outcomes. Data could lead to policy or to testing that could later inform policy.

Thornton asked McDonald how the Federal Plan for ELTRR will measure progress. McDonald noted that the plan’s implementation is still in the early stages, but there is interest in better measurement, different ways of measuring (e.g., of the vital conditions), and in engaging community, including in measuring protective factors and assets.

Thornton asked about the work of connecting across different domains of measurement to inform action. Kaufman said the first step is to bring people together and acknowledged that there is little collaboration between departments of education and public health because so many systems are siloed resulting in few opportunities to collaborate. Crutchfield noted that many government departments, such as housing and community development, have shared constituencies and serve the same populations, and it is easy to connect with them. Federal entities are not impossible to reach, but doing so requires some navigation and different kinds of engagement—submitting public comment, writing to elected officials, and visiting one’s own state delegation to Congress. She added that her organization encourages clients to reach out to decision makers.

Thornton echoed Alberti’s earlier comment about health care being “the small voice in the room and the big ears listening to understand what the priorities of the other sectors really are.” Thornton pointed out that although there are entitlement programs for nutrition and health insurance for children, the U.S. does not have an entitlement for housing, which creates a challenge for pediatricians like herself. She called for health providers to amplify the priorities of other sectors, such as investments outside of health care.

Responding to a question about data interoperability, Thornton said that obtaining data across payers in a geographic area is challenging, and there are issues—such as lack of granularity and subpopulations—with public health data. Baxter said there are federal stan-

![]()

dards on interoperability and the obligation to share data, although adherence is not ideal and there are problems with data hoarding by both public- and private-sector organizations. An audience member said that data on mortality, communicable diseases, cancer, and other outcomes are increasingly geocoded and “processed and delivered at fine-grained geographic levels,” but it is not clear that the communities that need access to those data can get them or get them in a usable form.

An audience member asked about interventions that address the social, structural, and historical drivers of inequity. Crutchfield mentioned community benefit agreements and other opportunities for organizations based in a specific geographic area to work alone or partner with others in responding to community needs, such as housing mobility. Responding to comments about the utility of claims data, Thornton noted that in the context of health equity measures, health care use data is unlikely to be helpful, given disparities in access and use.

CLOSING REFLECTIONS

Raymond Baxter described the workshop as “grounded in science…anchored in social justice, and…driven by our obligation to act.” The event began with the definitions of health equity measurement, then turned to the state of the science, its complexity, and its relation to power and to action. A session illuminated the dynamic domain of changing identities and definitions of race and ethnicity and implications for the field. Speakers then explored how measures describe problems or progress, and drive change through the power of narratives.

Baxter said “internal adoption and external compliance can work in tandem, or separately, or against each other to drive change in organizations and in adoption of changes.” Speakers also explored power dynamics, accountability, governance, and how communities cocreate measures and drive the agenda. The last panel featured discussions about multisector measures to inform the work of changing the conditions for vibrant and thriving communities, Baxter noted, adding that the challenge is coming together to create an impact. He called on the audience to continue to think about what they have learned, to make sense of it, and integrate it into their work.

![]()

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief has been prepared by Alina Baciu as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteurs or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

*The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief rests with the institution. This workshop was planned by Sheri Johnson (Chair), University of Wisconsin, Madison; Philip Alberti, Association of American Medical Colleges; Hanh Cao Yu, The California Endowment; Fernando De Maio, DePaul University and the American Medical Association; Rachel Thornton, Nemours; Ana Jackson, Blue Sheild of California Foundation.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Zoe R. F. Freggens, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Patricia C. Heyn, Marymount University; and Michael C. Samuel, California Department of Public Health. Leslie Sim, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS This workshop was partially supported by Association of American Medical Colleges, Blue Shield of California Foundation, Fannie E. Rippel Foundation, Jefferson University, Nemours, NY Langone School of Medicine, The California Endowment, the Kresge Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

STAFF Maggie Anderson, Research Assistant; Alexandra Andrada, Program Officer; Alina Baciu, Roundtable Director; Ronique Taffe, Program Officer; and Stephanie Puwalski, Research Associate.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/the-ecosystem-of-health-equity-measures-a-workshop.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. The ecosystem of health equity measures: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27914.