Climate Change and Human Migration: An Earth Systems Science Perspective: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Mechanisms and Pathways for Modeling the Impacts of Catastrophic Events on Human Migration

3

Mechanisms and Pathways for Modeling the Impacts of Catastrophic Events on Human Migration

In Session 1, speakers examined how rapid-onset catastrophic events such as severe storms may prompt human migration, including the interplay of natural and social processes under which stress-induced migration occurs as well as factors that can contribute to the resiliency of communities. Speakers from a range of disciplines discussed the mechanisms and pathways through which catastrophic events intersect with migration patterns and infrastructure.

FLOODS, DROUGHTS, AND HUMAN MOBILITY

Giuliano Di Baldassare (Uppsala University) spoke about the complex interactions and feedback mechanisms among hydrological, climatic, and social processes. He described research showing that climate-related migration mostly consists of temporary, local, and rural-to-urban mobility and discussed how water infrastructure can play a major role in influencing where people live and move.

Noting that climate-related migration rarely involves crossing national borders, Di Baldassare said that studying climate-related mobility is complex because it is often difficult to differentiate between drivers and to understand how agency factors into decision making (Schutte et al. 2021). The most vulnerable groups are the ones who have the fewest resources for moving and are therefore most likely to be trapped in place, he said. The empirical research, especially in the social sciences, shows that migration that takes place in response to extreme events such as intense flooding is often short-term local and/or rural-to-urban migration (IPCC 2014).

To study the relationship between climate-related events and changes in the spatial distribution of human settlements, Di Baldassare and colleagues use various types of survey analysis to examine local case studies and proxies to perform global studies of the distribution of human populations. For example, satellite images showing nighttime lights can be used to capture changes in human settlements over time, an approach the researchers used to study how the human settlement grew further from rivers over time (Mård et al. 2018). Countries experiencing the most flood fatalities, such as Mozambique, had the most increased distance of resettlement from the river over time as measured by the distance of the center-of-mass settlement from the river. This pattern of migration is less observed in countries with higher levels of structural flood protection (e.g., major levee systems), such as the Netherlands. In another study exploring the role of water infrastructure in mediating the link between floods, droughts, and human mobility in agro-pastoralist communities (Piemontese et al. 2024), the researchers found that when drought occurred, organizations try to cope by increasing the water supply. However, without effective governance, this tended to reduce mobility, an essential element of resiliency for pastoralist communities in response to climate change and drought.

When examining the link between climate change or climate-related extremes and human migration, Di Baldassare said that it is important to understand multiple perspectives because of the strong feedback mechanisms present. The complex interplay between dams, water supply, and population dynamics provides one example. Although water infrastructure is built to cope with growing population to meet increasing water demands, the presence of dams and increasing water supply itself is a driver of growing water demands. This increase in water supply and water demand has led to unsustainable water consumption, for instance, in the U.S. Southwest (Di Baldassarre et al. 2021). This feedback mechanism shows that the distribution of population and human mobility is not only a response to but also a driver of climate-related risk. In another study, researchers found that an increase in flood fatalities in Africa was primarily explained by population growth in flood-prone areas (Di Baldassarre et al. 2010), where in-migration increased people’s risk from flooding but could also be a response to drought conditions, which has made settling close to the river more appealing.

During the discussion, Di Baldassare elaborated further on the relationship between policy, migration, and infrastructure. He emphasized the importance of research of studying these issues as coupled natural–human systems, which can expose the consequences of the interactions at play, such as increased vulnerability to drought and groundwater exploitation. This can help to reveal the risks and undesirable conditions arising from the legacy of water infrastructure and thus better inform decision making.

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE

Nina Lam (Louisiana State University) discussed climate change and human migration from the viewpoint of community resilience and mobility. “Human migration away from a place means that the place is not resilient,” she said. “In the long term, resilience is sustainability.” Describing her experiences studying community resilience and relocation in southeast Louisiana, an area that regularly experiences hurricanes and other severe events in addition to threats from rising sea levels, Lam emphasized that understanding disaster resilience begins with measuring it.

Lam and colleagues studied factors that influenced the return of small businesses after Hurricane Katrina, which, she noted, are important to local economies. They found that critical infrastructure protection—such as levee protections, utilities, and telecommunication—were the main factors involved in decisions to return. Lam noted that these same factors may impact human migration away from a place that has endured multiple climate-related events. In addition, the research suggested that emergency plans to help repair damaged property and rapidly restore infrastructure, resuming education and health services, and providing recovery aid to small businesses can help to improve social resilience and increase the likelihood that businesses will return after an event.

The Resilience Inference Measurement (RIM) model can be used to identify the social and environmental factors that make a community resilient. The model uses data on hazard threat, damage, and recovery to establish resilience scores and identify specific social and environmental capacities that contribute to community resilience. While these factors can be useful for examining the dynamics present in a community, Lam noted that getting the data on hazard threats is key to applying this method. The frequency or intensity of past natural hazards may be known, but predicting the location and frequency of future hazards is more challenging. To model indirect effects of environmental factors on population change with a system-dynamic model of migration in southeast Louisiana, Lam and colleagues extended from the RIM model to a dynamic resilience analysis using a Bayesian network (Lam et al. 2018). The results from a simulation using this model showed that the area closer to New Orleans would not be sustainable and would lose population in the next 50 years. The researchers also identified some hypothetical tipping points and possible mitigations that could affect this population loss; however, Lam noted that the accuracy of the models is constrained by limitations in data quality.

In another project, researchers surveyed more than 1,000 residents of southeast Louisiana for insights into how residents there think about moving. They found that 22 percent had considered moving, a relatively high proportion given that the average migration nationally is 11 percent. More

than 25 percent of participants had experienced flooding from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. Based on the survey, the researchers developed a decision model that showed how economics was actually more important than flooding in influencing relocation decisions in this vulnerable coastal area (Correll et al. 2021). In other words, Lam said, there must be economic opportunities available at the new location.

In some cases, an area may become uninhabitable, such as parts of coastal Louisiana due to land loss. For example, Lam pointed out that a Louisiana tribe became America’s first climate refugees in 2016 when they had to relocate from Isle de Jean Charles due to the loss of 98 percent of their cultural land. In such extreme cases, as well as in situations when relocation is voluntary, Lam said that it is important to consider where people are moving to. Although migration to economically prosperous areas is desirable, people can also find themselves exposed to different risks, such as inland flooding, underscoring the complexity of balancing economic opportunities with environmental hazards. Lam added that the rising cost of flood insurance in Louisiana further exacerbates these issues, potentially leading to socioeconomic disparities in affected regions.

Lam ended by emphasizing that the broader context of resilience is crucial in addressing climate-induced migration. Questions about what constitutes community resilience and how to measure it remain pivotal. A comprehensive approach that acknowledges the interconnectedness of natural and human systems and captures the adaptive capacity of communities to bolster resilience is needed to address climate-induced migration, Lam said.

CHANGING HUMAN SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Serena Ceola (University of Bologna) described how researchers can combine multiple types of data to shed light on climate extremes and changes in human settlement patterns. She highlighted examples of methods used to study the relationships between droughts and settlement patterns in Africa, along with insights gained through this research.

Droughts are among the most devastating hydrologic extremes in terms of both human lives and economic impacts, and climate change is increasing the likelihood and severity of droughts globally (AghaKouchak et al. 2014). An analysis of data from 1970 to 2019 showed that droughts represented only 7 percent of natural disasters during that period but were responsible for 34 percent of disaster-related fatalities (WMO 2021). Droughts in Africa have become particularly intense, frequent, and widespread over the past 50 years (IPCC 2023a; Masih et al. 2014).

As Mankin noted, short-distance mobility within national borders is the most prevalent form of migration (Caretta et al. 2022; Hoffmann et al.

2020; Xu and Famiglietti 2023). About half of the world’s urban population is living in areas where migration has accelerated urban population growth (Niva et al. 2023), and disaster displacements are three times larger than displacements associated with conflicts and violence (Anzellini et al. 2020). Ceola noted that all climate change impacts, but especially hydrologic extremes such as floods and droughts, are affecting the risk that comes with migration, whether in the short term or permanently (Caretta et al. 2022).

A recent study examined associations between drought occurrences and human mobility toward urban areas in Africa between 1992 and 2013 (Ceola et al. 2023). For this work, the researchers used multiple data types, including data on annual drought occurrences from weather and emergency event databases, nighttime light analyses, geospatial data on the location of rivers, and urban population data from the World Bank. The results showed that droughts are influencing patterns of human settlements in Africa, with 74 percent of African countries seeing people move closer to rivers and 51 percent seeing people move closer to urban areas. Ceola said that one implication of this pattern of migration is that floods can cause more fatalities when they occur after a drought has driven people to move closer to the river. She also noted that some studies have predicted that the population living in Africa’s drylands will double by 2050, which could set the stage for Africa’s rapidly growing cities to become risk hotspots for both climate change and associated human displacements.

CREATING A MORE HOLISTIC VIEW OF RISK

Elizabeth Marino (Oregon State University Cascades) spoke about how meso-level factors such as property law and regulations can shape the way that risk is perceived and the way that planned and unplanned relocations happen in the wake of flooding disasters. She highlighted examples from a recent book featuring case studies from across the United States (Jerolleman et al. 2024) and a photo exhibit focused on places that are vulnerable to flooding and other disasters (Knowledge Is Power Exhibit n.d.).

She noted that there are complex social, political, and economic conditions that drive human migration and, as the impacts of climate change expand, resettlements linked to storms have become emblematic of climate change impacts. Marino posited that this new visibility around climate migration has created its own set of challenges, one of which is an oversimplified view of climate as a driver of migration. In Isle de Jean Charles, for example, she said, the history that has led to the current pattern of depopulation is more complex than sea-level rise. She noted that the Isle de Jean Charles is outside the levee system, leaving the island even more susceptible to storms. Disinvestment by the state and federal governments in protecting the road

that provides access to the island made it difficult for people who needed reliable access to the mainland (e.g., for jobs or school). This led to a drop in population and meant that the island was even less likely to meet cost-benefit calculations for hazard mitigation measures, which may all be factors in migration.

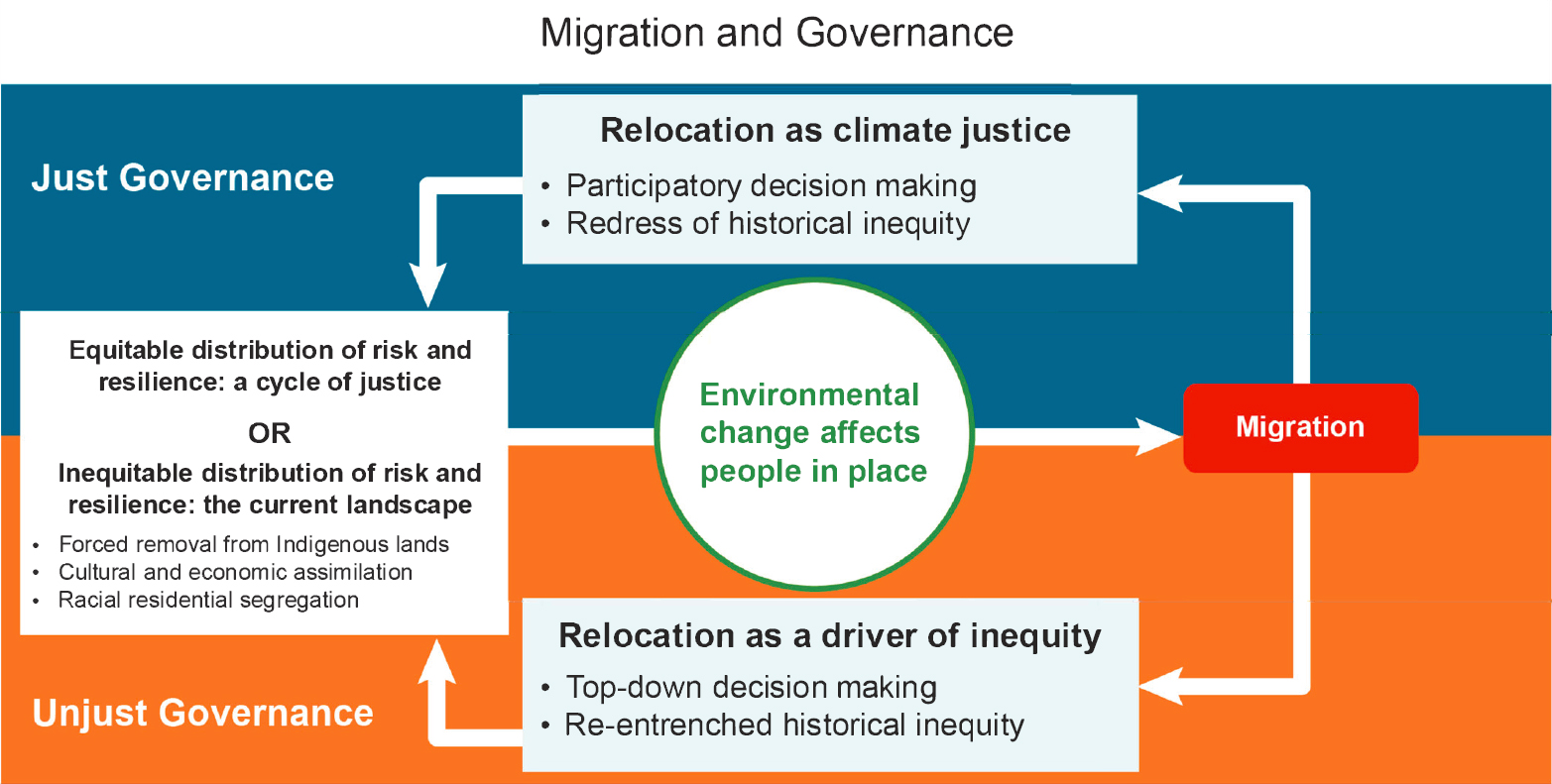

It is critical to not only study whether people move or for how long and in what direction but also what their lives are like after the move occurs and why, Marino said. Relocation can result in an unbalanced distribution of risk and resilience, driving further inequity (Figure 3-1). She described a model that incorporates the policy landscape impact on people, communities, industrial activities, and development to understand risk exposures and opportunities after relocation. This model where climate impacts intersect with how laws and regulatory structures funnel risk into and away from certain areas may offer insight about historical and contemporary vulnerabilities, Marino said.

During the discussion, Marino highlighted additional complexities of relocation decisions, particularly in the context of environmental changes such as coastal shifts. She emphasized that while conventional analyses often treat relocation as a one-time decision aimed at reducing risk, people assess relocation differently, weighing the potential disruption to their livelihoods, family, and social ties against the promise of a better future. She suggested that there is a need to reframe the discussion to focus on maintaining cohesive livelihoods and sociocultural narratives during relocations, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of such decisions.

SOURCE: Presented by Elizabeth Marino on March 18, 2024.

This page intentionally left blank.