Climate Change and Human Migration: An Earth Systems Science Perspective: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 Overview on Climate Change and Human Migration: Current Status and Research Gaps

2

Overview on Climate Change and Human Migration: Current Status and Research Gaps

Three keynote speakers set the stage for the workshop for a multifaceted exploration of climate change and human migration. Speakers provided an overview of different approaches to studying the topic, shared their perspectives on the current state of knowledge, and highlighted gaps that could be further explored.

INTEGRATING AN EARTH SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE

Justin Mankin (Dartmouth College) began the session by discussing the merits and challenges of viewing climate migration using an Earth systems perspective. He posited that adopting an Earth systems perspective on climate migration is valuable, but he cautioned that it is essential to rectify data gaps in order to avoid reinforcing overly reductive and deterministic models of human tragedy.

He noted that people are paying more attention to climate change as temperatures continue to break records at an accelerating pace and as the impacts of climate change grow increasingly apparent in daily life for many. For example, a person born in 1950 has now experienced more than a year’s worth of daily temperature records, or around 365 new temperature records, while a person born today can expect to reach that threshold of a year’s worth of additional records in the next 25 years. These changes come with staggering costs, he said. Based on econometric modeling, Mankin’s team estimated that about $30 trillion worth of global macroeconomic income losses were due to extreme heat from 1992 to 2013 (Callahan and Mankin 2022). They also estimated that an El Niño event in the tropical

Pacific that began in March 2023 will be associated with losses on the order of $4 million to $5 trillion globally, disproportionately impacting the most vulnerable (Callahan and Mankin 2023). All of these impacts are happening amid a wider geopolitical context and social upheavals, which together drive people to move in order to manage their exposure and stress, Mankin said, noting that 1 in 75 people faced social disruptions that forced them to move in 2022, with more than half of those moves being internal displacements.

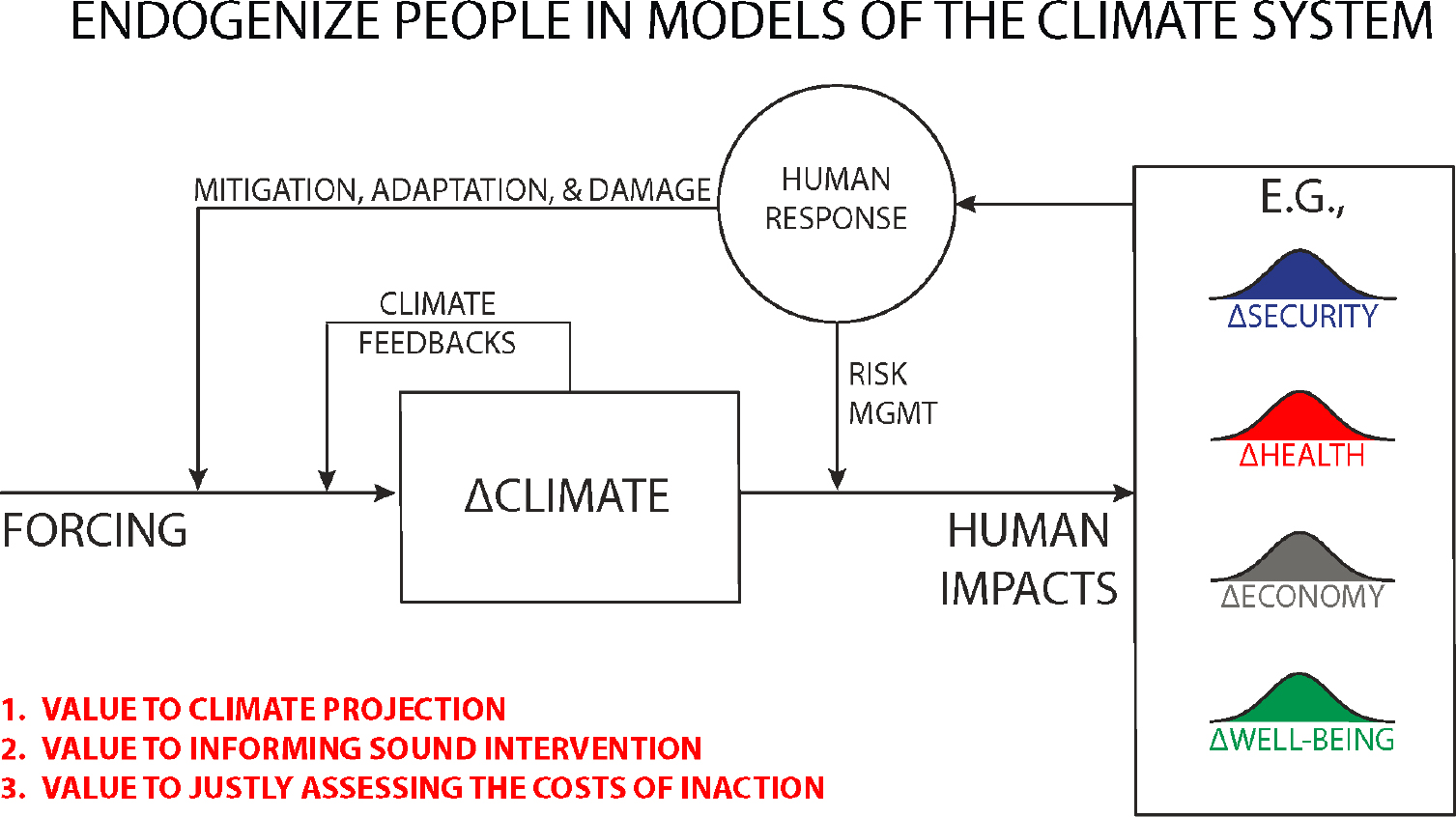

The value of using an Earth systems approach is that it considers the coupled dynamics of a system, and Mankin suggested that meaningfully incorporating people into models of the climate system can shed light on both future climate changes and the human impacts of those changes. He presented a framework that depicts how climate forcing leads to climate change, which induces a set of impacts that alter human well-being, which in turn induce a human response that feeds back into the process (Figure 2-1). Human responses to climate impacts can come in myriad forms and are projected onto complex socioeconomic and cultural landscapes, Mankin said, and he explained how this framework can help to elucidate the ways in which some responses may diminish exposure risks while others could produce feedbacks that further exacerbate climate change. To inform interventions aimed at managing climate change risks and understand the potential impacts of increased mobility and migration, he noted that it is important to recognize the extent to which warming influences those processes and vice versa.

Using this framework, Mankin and colleagues have traced the relationships between emissions and impacts, and results indicate that the countries that are suffering the greatest losses due to climate impacts are generally those that are the least responsible for global warming (Callahan and Mankin 2022b; Mankin and Callahan 2022). Pointing to the many equity and justice issues raised by the costs of climate change and adaptation, these findings underscore the importance of integrating people into the models through which we understand the climate system. However, there are also significant challenges in meaningfully integrating an Earth systems approach to climate migration. Disentangling causality includes reconciling different spatiotemporal scales, various types of uncertainty, and the different forms of prediction used across disciplines, Mankin said. He added that overcoming these challenges will involve figuring out the right balance between specificity and generalizability and determining what level of reduction is acceptable.

Another key challenge is that understanding the impacts of climate change necessitates both climate and social science data that are often unavailable or that come with significant uncertainties. The people and places that are the most vulnerable and exposed to climate impacts are

SOURCE: Presented by Justin Mankin on March 18, 2024.

also the least likely to have reliable data on the relevant physical and social processes underway in their communities, Mankin said. This suggests that impacts and costs are likely being systematically underestimated, making it difficult to develop meaningful interventions to respond. Mankin stressed while this data poverty is widely recognized on the social side, it also creates important limitations on the physical side. For physical data, he noted that many highly populated but lower-resourced regions do not have any weather observations at all, making it difficult to track climate impacts in the places that are least culpable for them, experience them first, and have the fewest resources to manage them. For example, while North America and Europe are replete with sources of data on weather and climate, the same is not true for South America, Africa, parts of the Middle East, South Asia, and the interior of Asia. Mankin said that a lack of climate data in places experiencing climate change first is a critical need to address data inequities around the globe (Figure 2-2).

INCORPORATING SOCIAL SCIENCES

Lori Hunter (University of Colorado Boulder) discussed approaches to studying migration—a complex social process—from a social science perspective. She noted that a report published by the World Bank projected that 140 million people would move within their countries by 2050 due to climate change (Rigaud et al. 2018), underscoring the scale of anticipated climate-related migration. When thinking about the drivers of migration, Hunter said, it is important to recognize how micro-level drivers, such as age, education, wealth, and marital status, interact with meso-level factors, such as social networks and policies, to influence a person’s decision to migrate or stay. These are also influenced by macro-level drivers, including political, demographic, and economic factors. Researchers captured some of these interactions in a framework that describes how environmental factors such as heat waves and drought interact with other processes to influence migration decision making (Black et al. 2011) (Figure 2-3). The complexity of the micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors at play in the context of climate-related migration makes it challenging to model migration decision making, Hunter said. She added that scale is also important to consider because the people making migration decisions are embedded in households, communities, and counties, and said that there is a critical need for accessible measures at different scales, pointing to a recent review that found many studies focused on precipitation or temperature more than other climate-related events (Hoffman et al. 2021).

Although modeling climate-related migration decision making presents a daunting challenge, various sources of data can offer useful insights. Hunter said that while there may generally be sufficient social data in terms of age, education, and gender of individuals as well as good environmental

NOTE: Global climate data collection is concentrated in North America, Europe, and Australia, while vast swaths of highly populous areas across Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and South America lack adequate climate data resources.

SOURCE: Presented by Justin Mankin on March 18, 2024.

SOURCES: Presented by Lori Hunter on March 18, 2024, from Black et al. (2011).

data on extreme events, temperature, and precipitation, the gap lies in bringing together those two kinds of data. For example, she noted that when people in the United States move across county boundaries, it is useful to know what extreme weather events have happened in that county, but this is only possible if data are available at the county level. The temporal scale is also important for understanding whether someone moves in response to an extreme event that happened last year or a series of events that have happened over the past 5 years.

Censuses can be a particularly useful data source for studying migration. For example, Hunter’s team used data from the 2000 and 2010 Mexican censuses to study migration from Mexico to the United States. After linking these data with community-scale information, the researchers observed that migration out of drought-stressed regions of Mexico was prominent, but only for communities with strong social networks in the United States. However, Hunter said that censuses usually capture only whether someone has moved in the past 5 years, making it challenging to link with environmental data covering other time frames. Surveys offer another useful data source. For example, researchers used surveys to study seasonal and circular migration (capturing whether a household member migrates to earn income as well as whether those migrants come back) in a community in a small district in Thailand for more than 20 years (Entwisle et al. 2020). They found that climate-related stress in the communities did not affect out-migration but did make it less likely that individuals who had moved would come back. Ecological analysis, which involves characterizing different spatial units, can also be used to examine migration. For example, researchers predicted sea-level rise from climate models of counties across the United States and then examined what migration flows might be expected at the county scale (Hauer 2017).

Environmental pressures come in many forms that intertwine with economic, cultural, and other factors, and Hunter stressed that migration is just one way that households can respond to climate change. She suggested that it would be useful to have more information on other types of adaptation strategies. Additionally, while many studies examine what pushes people out of some areas, she said that more research is needed to understand what might attract them into other ones. She also noted that people who cannot move or choose not to move may be an understudied group and added that it is important to consider the impact of agency in determining a person’s decision to move (or not), or whether they have no choice and thus no agency in the decision. She also suggested that it would be useful to improve methods for integrating qualitative insights, such as critical life and cross-generation experiences, with scientific knowledge. Finally, she suggested that fostering connections with policymakers could help ensure that the insights gained through studies of migration drivers can help to inform decision making.

CENTERING NATURE AND COMMUNITIES

Jacqualine Qataliña Schaeffer (Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium) highlighted the value of centering nature and local communities and cultures in making decisions about climate migration. Introducing herself in the Iñupiaq language, she emphasized the importance of preserving Indigenous languages due to the unique concepts they convey, which is relevant not only in cultural and social contexts but in scientific research as well. She described how historical factors such as U.S. government actions have influenced climate vulnerability in Alaska, a vast and diverse area that is home to 229 federally recognized tribes. For example, she said that disruptions to traditional seasonal migrations have isolated some communities on fragile land. Highlighting the philosophical perspective offered by Indigenous elders, she said that maintaining balance entails understanding Earth’s place in the universe, sharing the story of people’s interconnections, and cultivating a harmonious relationship with nature.

“For 500 generations we have lived on the same geographic spot on the planet—we have not migrated,” said Schaeffer. “We still eat our traditional seasonal foods that my ancestors ate. Why is this important? Because there is much to learn from people who have adapted over time. Even though our history is oral history, those stories are compelling when you cross them into science.” She added that it is useful to consider the movement of people side by side with the movement of animals and other living organisms because they often presage change, underscoring the insights that can be gained from fostering connections with nature and the environment.

Of the 229 tribes in Alaska, Schaeffer said that 144 are environmentally threatened, and most likely every community in Alaska is being affected in some way by climate change. Alaska is warming three to four times faster than most other places on the planet, and the impacts are real, Schaeffer stressed. Yet, she lamented, many of the decisions affecting these communities are made elsewhere, by people who do not understand the environment, cultures, and interconnections between people and the environment that exist there. As an example, she pointed to the challenges faced in one village she visited that had no water and sanitation services and faced temperature extremes from −70°F (February) to 102°F (August). She noted that it is extremely difficult to engineer water and sanitation systems that work in these types of temperature extremes and that the inequities in Alaska are extreme and many communities are not even near the same baseline as many other Americans in terms of access to basic services. Additionally, she said that many people in Alaska do not want to move because they are on the lands of their ancestors, and their culture and value system emphasizes their role in stewarding that land and keeping those environments healthy.

The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, a statewide tribal health network, examines environmental impacts through a tribal health lens. Schaeffer contrasted this with the Western approach to science and research, which often operates in silos without considering the psychological, mental, and behavioral health impacts of environmental pressures. She also noted that the recovery and response system in the United States is mostly reactionary when it comes to climate impacts—a mindset of waiting for disasters to happen rather than preparing for them. She suggested that for this perspective to change, there is a need for data from places such as the Arctic, where climate change is happening especially rapidly. The impacts in Alaska have been severe, including flooding, erosion, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events. As an example, Schaeffer pointed to a typhoon that washed away Indigenous fish camps that contained local communities’ food resources for the year; she noted that policymakers who do not understand the way of life in these communities considered the fish camps to be recreational and thus were unprepared to adequately respond.

A report from the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium calls out challenges and inequities that are currently present across the system and provides recommendations on how to respond (ANTHC 2024). Schaeffer urged a focus on fostering curiosity to facilitate the connection and cross-pollination of different knowledge systems for greater understanding and impact moving forward. She said that having different worldviews does not preclude Indigenous communities and scientists from working together to support shared goals and the planet that we all treasure. Drawing from the wisdom of Indigenous elders—who are deeply knowledgeable about how ice systems affect broader ecological systems, including water levels, temperatures, and weather cycles—she emphasized the importance of understanding humanity’s connections with our environment and closed with a message of hope that by embracing our shared history with nature, we can listen, learn, and adapt.

This page intentionally left blank.