Programs and Frameworks for Autism Interventions: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2024)

Chapter: Programs and Frameworks for Autism Interventions: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

Programs and Frameworks for Autism Interventions

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine were asked to appoint a committee to conduct an Independent Analysis of the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) Comprehensive Autism Care Demonstration (ACD). As part of this effort, the committee was tasked to address nine areas identified, and later amended, in Section 737 of Public Law 117-81, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022. These tasks included “a review of any guidelines and industry standards of care” related to applied behavior analysis (ABA) (a prominent intervention for those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder [ASD]).1 To hear perspectives on standards of care and inform the committee, the National Academies hosted a public workshop on June 20, 2024, to learn about updates relevant to the ACD and about frameworks for neurodiversity-affirming and trauma-informed care, particularly as they might affect the provision of ABA. Workshop presentations provided background on federal programs, including the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs’ (CDMRP’s) Autism Research Program (ARP),2 the Exceptional Family Member Program (EFMP),3 as well as the ACD. Presentations also provided perspectives on the state of evidence for ABA and perspectives on neurodiversity-affirming and trauma-informed care. This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief summarizes the presentations and discussions expressed during the public session that were aimed at helping the committee better understand the context surrounding the ACD and the use of ABA as an intervention for ASD and should not be seen as a consensus of the workshop participants, the committee, or the National Academies.4

FEDERAL PROGRAMS

Through the Defense Health Agency (DHA), DoD is responsible for TRICARE, a health benefit program with approximately 9.6 million beneficiaries, including active-duty personnel, Reserve Component personnel, military retirees, and their families. Because ABA has yet to be established as medical care under the medical benefit coverage requirements that govern TRICARE, the ACD, authorized through 2028, provides reimbursement for ABA to TRICARE-eligible beneficiaries diagnosed with ASD. The purpose of the ACD is also to evaluate the delivery of ABA.5 Other DoD programs also play a role in evaluating autism interventions and providing support to

__________________

1 For more information on the nine areas of interest for the committee’s independent analysis, see: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/independent-analysis-of-department-of-defensescomprehensive-autism-care-demonstration-program

2 For more information see: https://cdmrp.health.mil/arp/default

3 For more information see: https://www.militaryonesource.mil/special-needs/efmp

4 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/41339_06-2024_independent-analysis-of-the-comprehensive-autism-care-demonstration-program-meeting-3

5 See https://manuals.health.mil/pages/DisplayManualHtmlFile/202205-24/AsOf/to15/c18s4.html

![]()

families and beneficiaries with ASD. This section summarizes presentations on CDMRP’s ARP, EFMP, as well as DHA and the ACD.

CDMRP’S ARP

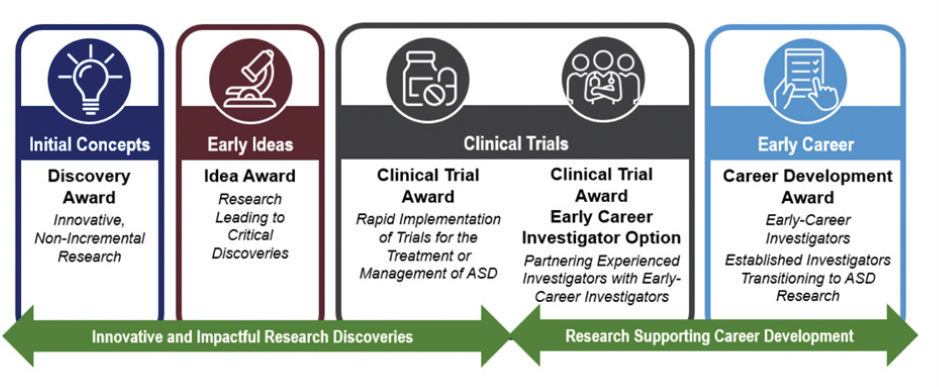

Nicole Williams (program manager, CDMRP’s ARP), shared the mission of CDMRP, which is “to responsibly manage collaborative research that discovers, develops, and delivers health care solutions for service members, their families, veterans, and the American public.” Stemming from grassroots efforts by breast cancer advocates 30 years ago, CDMRP’s goal is to transform health care through innovative and impactful research. She explained that CDMRP’s two-tier review process (i.e., peer and programmatic) involves scientists, clinicians, as well as consumer advocates.6 Throughout their programs and processes, CDMRP utilizes the expertise of scientists, clinicians, and the lived experience of consumer advocates to accelerate research and advance cures, improvements, and breakthroughs. ARP’s vision is to improve the lives of individuals with ASD now and in the future through promoting innovative research across the research continuum, including initial concepts, clinical trials, as well as the study of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions (Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, n.d.; see Figure 1).

Appropriations for ARP have risen to $15 million since 2020. One key element of ARP’s strategic direction is to recruit and retain early-career investigators focused on autism research by offering mentored and career development awards. Williams highlighted that she has seen an increase over the last several years in early-career investigators who are researchers with autism.

Williams then addressed CDMRP’s strategic plan, which outlines research goals to provide visibility not only for the research community but also for the autistic community. Each year, a programmatic panel discusses needs in the autism community, underfunded research areas and gaps, and how the program’s intent can be focused to ensure it is fulfilling the needs of the autism community. ARP’s specific strategic goals are to:

- Advance Effective Treatments and Interventions for Autism

- Address Needs of Persons with Autism into Adulthood

- Support Those Caring for the Autistic Community

- Understand Causes, Mechanisms, and Signs of ASD

Williams explained that the largest investment (59% of the portfolio) has gone to funding the first goal of advancing effective treatments and interventions for autism. In closing, she shared two ABA-centered studies managed by CDMRP. The first demonstrated that using tele-video-based instructions was effective in training military parents of children with autism and adults to become ABA tutors.7 The second study, in progress, is

SOURCE: Nicole Williams presentation, June 20, 2024. Autism Research Program, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs.

__________________

6 For more information see: https://cdmrp.health.mil/about/2tierRevProcess

7 For more information see: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32989771

![]()

comparing early intensive behavioral intervention against adaptive modular ABA in a 24-week randomized controlled trial (RCT).8

Exceptional Family Member Program

Tomeshia Barnes (associate director, Office of Special Needs, DoD) explained that involvement in EFMP is mandatory for active-duty service members who have a family member with a special medical or educational need as well as mandatory for those participating in the ACD. EFMP has three operation components: identification and enrollment in EFMP of families with dependents (or family members) who have special medical or educational needs; assignment coordination when families relocate to a new duty station; and family support in navigating and accessing federal, state, and local services (information referral and nonclinical case management services). EFMP does not provide medical care, she said, but provides family support services to those enrolled in addition to other care they receive. A recent focus of the Office of Special Needs is the standardization of EFMP across the department for families regardless of their service affiliation or location, highlighted Barnes. This included standardization of the policy requirement, the enrollment process, and the enhancement of family support. These enhancements include ensuring that families receive an annual personal contact to assist them in navigating and accessing services, ensuring that assistance is available to help families when they are relocating to a new installation, and enhancing data collection to ensure families transition and move through components of the program in a timely manner. These enhancements are also intended to ensure that families are connected with all of the available resources that they need. The office is continuing to enhance and improve the program in hopes to better support the families enrolled in the program and prevent families from falling through the cracks. When asked to expand on the EFMP relationship with DHA and the new requirements for an autism services navigator under the ACD, Barnes said that EFMP supports providers developing close relationships and partnerships with TRICARE case managers, autism services navigators, and all entities. The purpose of this relationship is to better support families and ensure timely connection to the services that they need. She said that they will continue to strengthen this existing collaboration partnership as new entities and different positions come on board. Similarly, a participant asked about outcomes, measures, or oversight to determine the efficacy of mandatory enrollment in EFMP and other policies. Barnes responded that their standardization efforts involved modifying how compliance is conducted and considered three components: access, execution, and satisfaction. In the case of mandatory enrollment for the ACD, there are built-in performance metrics that measure process cycle time to ensure that all components are processed in a timely manner. She added that they do not just assess access to the services and supports that EFMP provides, but also the access to services and supports within military communities as well.

DHA and the ACD

Krystyna Bienia (clinical psychologist and clinical program lead supporting the ACD) spoke on the demonstration, emphasizing that DHA’s focus is on clinically necessary health care and that TRICARE benefits are governed by statute and regulation and executed by the managed care support contractors through TRICARE per the operation manuals. ABA services are currently authorized under the ACD as there has not yet been a determination for ABA as proven medical care under these specific statutes and regulations, she explained. The authority as a demonstration provides the most flexibility to provide reimbursement for ABA services while the benefits of ABA and the evolution of the ABA field are addressed, Bienia said. Furthermore, DHA received guidance from Congress to execute various components of the benefit, such as floor reimbursement rates, reporting requirements for population utilization and trends, and the collecting and reporting of health-related outcomes. However, the ACD has not conducted research into the efficacy of ABA as it has not been authorized to do so. She said, what DHA reported are observations on the data from the measures that were recommended by experts in the field. These measures were selected because they are repeatable, can be executed by a wide range of providers, and are the measures most used in the field and in research, Bienia reported. She emphasized that DHA is

__________________

8 For more information see: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04078061

![]()

open to recommendations for alternative measures as the field continues to evolve.

Overview of the TRICARE Covered ABA Services

When considering TRICARE coverage of ABA services, Bienia said that DHA looks at three main areas: diagnosis, services, and programmatic oversight. This lends itself to providing the right services for the right person at the right time, she said. Bienia stated that early diagnosis affords individuals earlier access to services and that the policy allows for select generalists and specialists to diagnose and refer for ABA services. In 2021, DHA expanded the type of clinicians who can diagnose autism, and at the same time, standardized the documentation of the diagnosis to balance the expansion with clinical competency, created the symptom checklist form that is in alignment with the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and improved diagnostic accuracy by identifying and treating other comorbidities, she said. Bienia then noted that since 2021, the ACD offers Autism Services Navigators who provide care coordination services to certain ACD participants and help facilitate referrals and transfers to care. DHA continues to review the ABA literature for additional guidance on the optimal dose, frequency, duration, and quality of services, as well as the level of parent engagement, she added. DHA has noted that the industry lacks standardized utilization management criteria, but Bienia acknowledged that an initial development of an outline for a standard of care exists. Finally, as part of its commitment to its beneficiaries, she said, DHA has a responsibility to provide programmatic oversight through audits, outcomes, and evaluation processes or practices to assess the utilization management criteria, outcome measures, treatment-based decision-making, and discharge processes. She acknowledged that while TRICARE’s oversight requirements executed by the managed care support contractor can be complex, these have resulted from DHA efforts to ensure quality, safe, and effective care as well as identify instances of fraud, waste, and abuse.

Requirements in areas such as diagnostic criteria, treatment plan criteria, medical documentation, and provider practice were borne from prior lack of compliance with written policy. For example, she said that through claims audits, DHA identified that board-certified behavior analysts (BCBAs) were not seeing their patients regularly (Bienia noted that the Council of Autism Service Provider Guidelines describes regular case oversight as recommending one to two hours per week for a 10-hour per week program). Claims data collected did not reflect this frequency, so a requirement for a minimum of one direct visit per month was put in place, with audits ensuring program compliance. Bienia also shared how the ACD has responded to family needs over time; for example, by adding the active provider placement contractor requirement. This requirement places beneficiaries with the first provider who meets the criteria for accepting a new referral and who has agreed to meet the ACD access to care standard. She added that these requirements enhance oversight by having real-time visibility on provider access and ensuring that families are not waiting for ABA services. She further stated that DHA is exploring the relationship between treatment adherence and outcomes.

Unlike commercial and Medicare insurance plans, TRICARE is a worldwide entitlement benefit that serves 9.5 million people, with 9 million beneficiaries residing in the continental United States, Bienia explained. TRICARE must be a uniform benefit for all beneficiaries. This includes implementing a program that oversees the clinical needs of every individual and responds to their health care needs. Guidance must be clear, she said, and program oversight must balance diagnosis, access, health care outcomes, and program compliance through monitoring and accountability, applied standardization, peer-based clinical necessity review processes, and continued evaluation.

Discussion

Responding to a question regarding the development of past, current, or future policies for the ACD, Bienia described the most recent ACD policy update. The 2021 policy update was a multi-year process that included feedback from funding sources, advocates, and small organizations as well as interested parties, including families, mental health providers, military medical treatment facility providers, professionals from other health care disciplines, managed support contractors, contract oversight, and other TRICARE program oversight person-

![]()

nel. Also incorporated into the policy update were lessons learned from administering the ACD. Additionally, administrators of TRICARE benefits oversaw and provided feedback on these interactions with stakeholders. She added that family feedback from surveys was also considered, as consistent themes and questions were raised.

In conclusion, Bienia highlighted one of the core challenges of administering the ACD is that behavior analytic principles can be applied to a variety of settings, people, and points in time, yet what is covered under TRICARE and the ACD is restricted by the authorizing legislative language. She added that determining what is reimbursable health care consistent with statute and regulations, and how that is defined, has been an ongoing consideration since the ACD was initiated.

ABA

As discussed in a prior public session of the committee (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2024), ABA is highly individualized, flexible, and dynamic. It is the application of the science of behavior analysis for clinical purposes. Generally, it stresses positive reinforcement to develop socially important skills. The following section summarizes presentations on the history and development of ABA and related interventions and presents perspectives on the evidence for these interventions.

ABA as an Intervention for ASD

ABA is not the only intervention for ASD, but it is one of the most prevalent, said Greg Robinson (deputy director of public policy, Autistic Self Advocacy Network). Developed in the 1960s and 1970s by Ole Ivar Lovaas at the University of California, Los Angeles, ABA was based on behaviorism, he said. It included the first early intervention models utilizing operant conditioning to modify behaviors using rewards and punishments. The intervention has received pushback from self-advocates and others, Robinson said, because early ABA practice relied heavily on physical punishments such as shouting, slaps, and electric shocks and some early research considered its application as gay conversion therapy. But the modern practice of ABA has since moved away from these measures and instead leans more heavily on withheld privileges and rewards while retaining many of the other core elements of the Lovaas approach, such as numerical data collection and the documentation of defined behaviors, according to Robinson. He remarked that the goal is often to reduce the presentation of external autistic traits, and there is significant focus on early intensive behavioral intervention. Over time, existing interventions for ASD have evolved and new ones have been developed, several of which involve behavior elements and tools, such as the Picture Exchange Communication System9 and pivotal response therapy.10

While Robinson acknowledged that ABA is frequently considered the gold standard of autism interventions, meta-analyses have typically found the evidence base regarding its effectiveness to be weak (Autistic Self Advocacy Network, 2021). But this is a problem with several therapeutic approaches, he noted, and many people understand that not every intervention can be studied in an RCT. But much of the current evidence comes from small sample studies or single-subject studies formulated around models that omit the perspectives of people with autism and often exclude individuals who are nonspeaking and individuals who have intellectual disabilities from participation. These include medical models that identify a deficit that needs to be corrected or approved and social models that identify a discourse between what an individual needs and what society is willing or able to accommodate, he said. While much more complex to execute, Robinson proposed the goal of intervention should focus on accommodating individual needs, which can relieve the psychological burden and lessen the risk of abuse. Other limitations of the small amount of evidence-based research in this space, Robinson said, include the relatively weak evidence of the persistence of improvements between settings; limited evidence of the correlation of dose-response (the number of hours spent receiving ABA) and improvement; and the lack of long-term cohort studies.

In conclusion, Robinson called for diversity in therapeutic interventions and raised ethical concerns surrounding the broad use of ABA with the autistic community. Appropriate levels of consent are often developmentally bound. For instance, what is appropriate for a two-year-old in

__________________

9 For more information see: https://nationalautismresources.com/the-picture-exchange-communication-system-pecs

10 For more information see: https://www.autismspeaks.org/pivotal-response-treatment-prt

![]()

terms of consent and assent is different than a 15-year-old, he noted. But even when consent is appropriate and necessary, it is only sometimes sought, Robinson said. This results in a lack of autonomy he noted, as well as ABA potentially targeting behaviors that may either be an individual withdrawing consent or are self-regulatory for that individual. Therefore, he argued, intervening to disrupt that behavior may not be in the best interest of the individual, and some studies fail to adequately report these potential adverse effects of the intervention.

Project ImPACT

Brooke Ingersoll (professor and director, Autism Lab, Michigan State University) discussed Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBIs) as a class of interventions combining developmental science with ABA principles. These child-centered approaches are conducted in natural settings and incorporate behavioral strategies within child-led activities, she said. According to Ingersoll, multiple studies, including RCTs and meta-analyses, have shown positive effects of NDBIs on children’s social communication, adaptive skills, and cognition (Sandbank et al., 2023). Ingersoll emphasized that these outcomes are not significantly moderated by child characteristics, interventionists, or intensity, suggesting versatility in implementation. She also commented on parent-mediated NDBIs, which have shown to be time- and cost-effective with improvements in well-being, but they are often underused in community settings. Project ImPACT,11 which Ingersoll co-developed with Anna Dvortcsak (private practice), is an example of this type of approach, focusing on young children’s core social communication skills and includes parent coaching strategies. Developed with input from parents, providers, and administrators, Project ImPACT is designed for use in the community settings and has been implemented in various settings, she explained. Ingersoll’s research shows that training parents in this approach increases their use of coaching strategies (Ingersoll et al., 2016) and improves children’s social communication skills, particularly in expressive language and socialization (Ingersoll et al., 2024). Additionally, she said, Project ImPACT has demonstrated consistent improvements in positive parenting and interaction quality, with some studies showing improvements in parental self-efficacy and reductions in parenting stress (Ingersoll et al, 2016).

In response to questions from the audience, Ingersoll explained that NDBIs such as Project ImPACT are considered ABA and are grounded in ABA principles. However, she highlighted a core difference that NDBIs are designed to be cross-disciplinary and are not exclusively limited to ABA practitioners. The way progress is monitored with NDBIs, however, differs from ABA approaches, said Ingersoll. Related to billing and coding, Ingersoll explained that professionals can bill for NDBIs under existing ABA codes when the service is provided by an ABA-certified professional. But complications may arise when non-ABA professionals try to do the same thing. Ingersoll said that if a BCBA or a Registered Behavior Technician is providing ABA-based services that are an NDBI, they should both be able to use ABA-based codes.

ABA Provider Perspective on the ACD

Hanna Rue (chief clinical officer, LEARN Behavioral) discussed the challenges she has experienced in providing ABA when working with TRICARE, particularly regarding restrictions on covering activities of daily living. In her experience, these restrictions are not found in the civilian population or working with payors like Medicaid, she noted. Rue outlined the key considerations for developing measurable objectives, including whether it is developmentally and culturally appropriate, medically necessary, and identified as a priority by the family. She highlighted the discrepancy between BCBA graduate training and TRICARE’s assessment requirements, which from her perspective results in the burden for training often falling to small practices that then need to outsource this training. Since 2019, Rue explained the American Medical Association has recognized ABA as meeting clinical efficacy requirements. To receive Current Procedural Terminology code designation, ABA had to demonstrate sufficient levels of evidence and expert opinion. She also noted that several other organizations—the U.S. Department of Labor, the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, the U.S. Surgeon General, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—have recognized ABA as an evidence-based practice.

__________________

11 For more information see: https://www.project-impact.org

![]()

Currently, the ACD contains barriers to families trying to access ABA, said Rue. Specifically, these include the 90-day requirement for autism services navigators to develop a comprehensive care plan with a strict six-month reassessment requirement and monthly billing of treatment plan modification that is accompanied by harsh penalties for providers if missed. These strict deadlines, she argued, do not reflect the daily lives of many military families, given deployments and other requirements that may contribute to missed appointments. For example, if a family misses a scheduled monthly treatment plan modification even by a day, a 10% penalty on all ABA claims for that beneficiary are recouped by the ACD for the entire six-month authorization.12 This puts the burden on small organizations to maintain treatment adherence and dissuades them from serving TRICARE families, she said. Rue suggested a consideration for the committee might be that ABA as a standard TRICARE benefit, which could remove numerous barriers currently faced by military families and service providers.

FRAMEWORKS SUPPORTING NEURODIVERSITY AND TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE

Speakers in this section discussed neurodiversity-affirming frameworks, the relationship with ABA, and culturally responsive, trauma-informed applications of ABA.

Neurodiversity-Affirming Framework

Matthew Lerner (associate professor and leader, Life Course Outcomes Program Area, A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, Drexel University) addressed what he called the misconception that affirming neurodiversity means that people do not also need supports. Understanding and respecting the experiences and autonomy of people with autism can coexist with interventions designed to support them, but this does not mean that individuals who need interventions are “broken.” His presentation described a framework to ground neurodiversity-affirming interventions in research and clinical work across the field (Lerner et al., 2023). Learning from working with traditionally marginalized communities, Lerner explained that when you can create spaces that are welcoming and supportive, you generally help everyone.

Lerner then commented on the idea of neurodiversity-affirming early interventions, expressing that the notion of diversity in ways brains exist applies beyond those in the autistic community. He stressed that this appreciation for neurodiversity challenges researchers to think carefully about the goals of interventions. This, in turn, would shift the focus of those goals toward supporting strengths and facilitating interdependence across the lifespan.

Proposed goals would prioritize physical and emotional safety to create inclusive programs, models, and spaces within an individual’s environment while also working to determine if that environment is conducive to this kind of intervention. The inclusion of adults with autism in the ABA profession and the design and delivery of models, programs, and interventions recognizes the value of lived experience and places importance on the collaboration of those with autism and those without, according to Lerner. A neurodiversity-affirming approach maximizes the strengths of the autistic community while appreciating their challenges and learns from the experiences of related communities. Lastly, he identified a need for the development of instruments and tools for assessing the fidelity of neurodiversity-affirming interventions, such as building a community-based capacity for feedback. This would allow for the integration of community-centered autistic perspectives into ABA, he said.

Neurodiversity Affirming Approaches and ABA

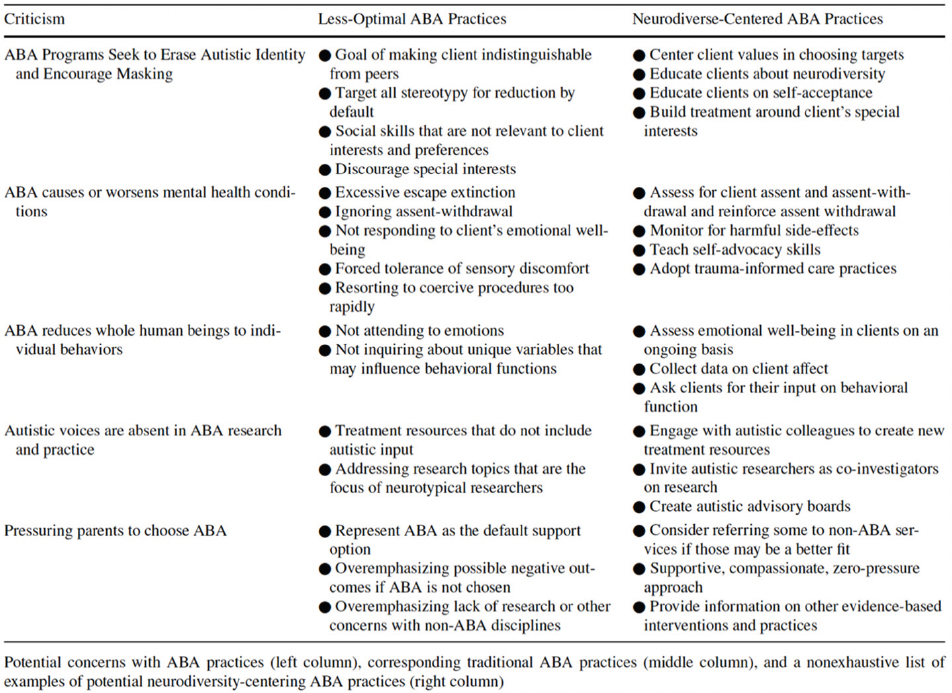

Sneha Mathur (BCBA and faculty member, Department of Psychology, University of Southern California) reinforced the importance of incorporating input from people with autism, understanding their concerns, and including them in the solutions offered. As Lerner introduced, this can be achieved by viewing autism through a social model lens, such as the neurodiversity paradigm.13 Mathur said that neurodiversity is a biological fact. The neurodiversity movement, however, is a social justice movement that seeks civil rights, equality, respect, and full societal inclusion for the neurodivergent. She explained that criticisms of ABA can emerge when ABA is viewed as correcting deficits. Instead of focusing on correcting deficits, the neurodiversity paradigm approaches autism as a form of divergence, not a deficit. The goal of the neurodiversity paradigm is to support researchers and practitioners in empowering people with autism to maximize their potential in a way that best serves their

__________________

12 See TRICARE Operations Manual section 8.11.6.2.3.3.

13 For more information see: https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/psychology-teacher-network/introductory-psychology/disability-models

![]()

values and goals, Mathur said. She went on to explain that the neurodiversity paradigm is an academic tool that addresses the feedback from the neurodiversity movement and explores how neurodiversity affirming care can be implemented in practice. This encourages researchers to reconceptualize treatment approaches as a collaborative process among experts in behavior, behavior analysts, and people with autism who are experts in their own lives. Mathur noted when autism is thought of as a neurocognitive variation without a negative connotation or implied medical pathology, it can be conceptualized as a combination of neurological differences and societal oppression. Often interventions focus on encouraging people with autism to modify their behaviors to reflect mainstream cultural norms and expectations. However, she said, what is considered normal varies by population and location. Therefore, the double empathy problem14 reconceptualizes this as a mutual lack of understanding of each other’s behaviors, with both neurotypical and neurodiverse groups of people needing to work toward understanding each other to achieve neuro-equality. This means, Mathur argued, that neuro-typical people need to make the world more accessible and inclusive for those with autism. She then shared her research addressing the common criticisms of ABA and outlined actionable steps to implement neurodiversity-affirming approaches in place of less optimal ABA strategies as outlined by Mathur et al. (2024; see Figure 2). In summary, Mathur said the goal of professionals should be on increasing quality of life, developing coping skills, and expanding a person’s strengths. They should center client values in choosing targets to work on, not imposed neurotypical values, she concluded.

Trauma-Informed Care

Adithyan Rajaraman (assistant professor of pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center) said that relative to

SOURCES: Sneha Mathur presentation, June 20, 2024 (Mathur et al., 2024).

__________________

![]()

the norm, people with autism and people from military and veteran families are at greater risk of encountering a potentially traumatic event. Introducing the concept of trauma-informed care, he explained this framework represents an amalgamation of strategies taken by practitioners intended to mitigate, rather than exacerbate, experienced or perceived trauma. The preventative nature of trauma-informed care suggests that it can be implemented without knowledge of the recipient’s trauma history or lack thereof. Rajaraman described the pillars of trauma-informed care as: (1) acknowledging the potential for trauma and the potential impact of that trauma; (2) promoting collaboration, shared governance, and choice-making across every aspect of service delivery; (3) ensuring safety and trust between client and care provider; and (4) emphasizing skill building. The goal is to empower individuals with self-advocacy, resiliency, and self-determination, he said, so that they can better navigate their own challenges. Rajaraman offered that trauma-informed care in ABA starts with providers acknowledging that individuals may have previous traumatic experiences, allowing them to filter clinical decision-making to prioritize minimizing harm and re-traumatization. Finally, he emphasized that a trauma-informed approach is possible and scalable within ABA.

Barriers to Providing Culturally Responsive and Safe Supports

Mari Cerda (director, Lighthouse Learning Center) spoke on the need to provide culturally responsive support, promote client self-determination, address past and present transgressions in ABA, and overcome barriers to care such as Western-centric practices that inadequately serve marginalized families. She highlighted the importance of identifying oppressive models, addressing systemic issues, and challenging interlocking behavioral contingencies that maintain the status quo (Glenn, 2004). Cerda pointed out the lack of guidance to improve cultural competency for clinicians in ABA, leaving it up to practitioners to create individualized and safe therapeutic interventions. There are also limitations in graduate programs making the practical application of ABA in trauma-informed settings more difficult, she said. Lastly, Cerda mentioned that there is a disconnect among researchers, policymakers, and current trauma-responsive practices when it comes to the implementation of these practices with many actors at various stages of readiness for implementation.

Cerda stressed the need for adequate compensation for expert-level care, noting the need for consistent oversight of technicians by a BCBA. Supervision, as well as more time for building authentic therapeutic relationships, also needs to be compensated, but it typically is not, she noted. Cerda called attention to the ways it is problematic to place the burden of becoming an expert in autism on caregivers, especially considering the compounding effects of past traumas, higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder by those who served in the military, and challenges faced by families of children with autism. Lastly, she encouraged a practice-led research focus to better reflect the reality of the autistic population and expressed support for neurodiversity-affirming and trauma-responsive practices, drawing from her own experiences as an individual with autism.

PUBLIC COMMENT OPPORTUNITY

To close the workshop, members of the public were given a chance to share their experiences. Participants highlighted difficulty finding providers who accept TRICARE, challenges with recent policy restrictions, deployments and frequent moves resulting in additional stressors for children with autism, and the specific challenges of newly diagnosed families who report feeling lost trying to access services. One commenter noted the benefits of trauma informed care in ABA, saying that such care helped the family manage meltdowns that were a result of a parent suddenly and unexpectedly being called away for long periods of time. Another commenter referred to the current statute limits on TRICARE coverage of ABA and noted that military service advocacy organizations are concerned that legislative changes are needed to ensure the military health benefit aligns with evolving technology, treatment protocols, and benchmarks established by commercial health plans and government payers.

Overall, several people called for aligning the ACD coverage with industry best practices, more flexible and comprehensive coverage, and better support for military families dealing with autism.

![]()

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders (5th ed.).

Autistic Self Advocacy Network. (2021). For whose benefit?: Evidence, ethics, and effectiveness of autism interventions. https://autisticadvocacy.org/policy/briefs/intervention-ethics

Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs. Autism. Department of Defense. https://cdmrp.health.mil/arp

Glenn, S. S. (2004). Individual behavior, culture, and social change. The Behavior Analyst, 27(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393175

Ingersoll, B., Frost, K. M., Straiton, D., Ramos, A. P., & Casagrande, K. (2024). Telehealth coaching in Project ImPACT indirectly affects children’s expressive language ability through parent intervention strategy use and child intentional communication: An RCT. Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society For Autism Research, 17(10), 2177–2187. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.3230

Ingersoll, B., Wainer, A. L., Berger, N. I., Pickard, K. E., & Bonter, N. (2016).Comparison of a Self-directed and therapist-assisted telehealth parent-mediated intervention for children with ASD: A pilot RCT. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 2275–2284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2755-z

Lerner, M. D., Gurba, A. N., & Gassner, D. L. 2023. A framework for neurodiversity-affirming interventions for autistic individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 91(9), 503–504. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/ccp0000839

Mathur, S. K., Renz, E., & Tarbox, J. (2024). Affirming neurodiversity within applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 17(2), 471–485. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s40617-024-00907-3

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024). Applied behavior analysis within the Department of Defense’s Comprehensive Autism Care Demonstration: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27800.

Sandbank, M., Bottema-Beutel, K., Crowley LaPoint, S., Feldman, J. I., Barrett, D. J., Caldwell, N., Dunham, K., Crank, J., Albarran, S., & Woynaroski, T. (2023). Autism intervention meta-analysis of early childhood studies (Project AIM): Updated systematic review and secondary analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 383, e076733. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-076733

![]()

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Megan Snair as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The statements made are those of the rapporteur or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Karen Ruedisueli, Director of Government Relations for Health Affairs, Military Officers Association of America. We also thank staff member Lida Beninson for reading and providing helpful comments on this manuscript. Kirsten Sampson Snyder, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

COMMITTEE MEMBERS George W. Rutherford, University of California, San Francisco (Chair); Brian A. Boyd, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Wendy K. Chung, Boston Children’s Hospital; Lauren Erickson, Institute for Exceptional Care; Eric M. Flake, Uniform Services University and the University of Washington; Patrick Heagerty, University of Washington; A. Pablo Juárez, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; Samuel L. Odom, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Jennifer E. Penhale, Colorado Developmental Disabilities Council; José E. Rodriguez, University of Utah Health; Andy Shih, Autism Speaks; Kristin Sohl, University of Missouri School of Medicine; Aubyn C. Stahmer, University of California, Davis, Mind Institute; Ruth E. Stein, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore; Allysa N. Ware, Family Voices; Zachary “Zack” J. Williams, Vanderbilt University Medical Center

SPONSORS This workshop was supported by a contract between the National Academy of Sciences and the Department of Defense’s Defense Health Agency (HT940223C000). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization or agency that provided support for the project.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/independent-analysis-of-department-of-defenses-comprehensive-autism-care-demonstration-program.

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. Programs and Frameworks for Autism Interventions: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/28030.