Considering Maternal Health Disparities: Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief (2024)

Chapter: Considering Maternal Health Disparities: Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief

|

Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief |

Considering Maternal Health Disparities

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

INTRODUCTION

From May through June 2024, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine held a five-part webinar series to explore social determinants of health that negatively affect maternal health outcomes.1 The webinars, organized by the Standing Committee on Reproductive Health, Equity, and Society and the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education, convened expert panels, including health care providers, researchers, and academicians, to share data and the lived experiences of pregnant women from historically marginalized communities. The topics included (1) maternal mental health and the work of doulas, (2) community-based organizations and innovative models of care, (3) outcome studies of maternal health care and disparities within active-duty service, (4) understanding micro-aggression and implicit bias awareness, and (5) building trust in health care among historically marginalized pregnant women.

This Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief summarizes the presentations and discussions across the five webinars. The views described are those of individual workshop participants. This document should not be viewed as providing consensus conclusions or recommendations of the National Academies.

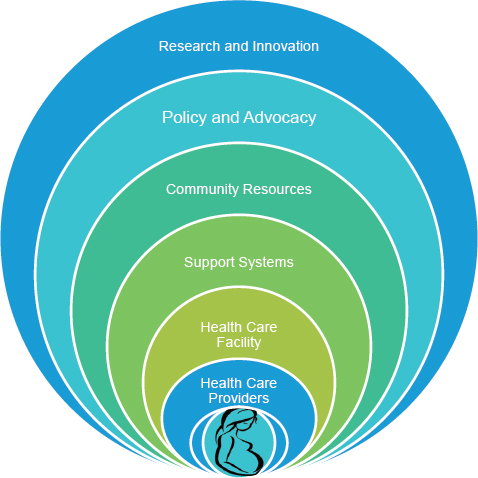

Karen McDonnell of George Washington University provided framing remarks for the webinar series. She explained that the panels would examine maternal health disparities through a social and structural determinants of health lens, which, according to the World Health Organization, are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, play, and age.2 These conditions give rise to health inequities, or unfair and avoidable differences in health status seen within and between different groups, she said. McDonnell described an expansive “maternal health ecosystem” (see Figure 1) that extends beyond health care services to encompass social, economic, cultural, and environmental determinants of health as well as income, education, housing, social support networks, and access to safe environments. McDonnell emphasized that addressing the complexities of the maternal health ecosystem requires a multi-sectoral approach to combine health care with community engagement, public health, education, policy, advocacy, research and innovation.

___________________

1 For more information and archived recordings, see https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/maternal-health-disparities-the-women-be-hind-the-data-a-webinar-series (accessed October 11, 2024).

2 For more information, see https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed August 27, 2024).

SOURCE: Presented by speaker Karen McDonnell in public session held May 3, 2024.

MATERNAL MENTAL HEALTH AND THE WORK OF DOULAS

Monica McLemore of the University of Washington opened the first session by explaining that maternal and infant morbidity and mortality are significant problems in the United States. She said that more attention must be paid to pregnancy in and of itself rather than solely on its outcomes, and she emphasized the important role of doulas in supporting individuals throughout their pregnancies.

A trained mental health counselor, Jasmine L. Garland McKinney of the University of Maryland discussed the psychological needs of women in underserved communities and explained how doulas have an important role in supporting the mental health of Black women. “Black women and birthing people are two times more likely than White women to experience a maternal mental health condition,”3 she said, “and are also two to three times more likely to experience maternal death.”4 Garland McKinney added that Black women experience unique “race-related perinatal psychological stressors,” a term she coined to describe experiences related to the historic and ongoing mistreatment of Black women in the United States, which in turn may contribute to stress specific to Black women’s perinatal experiences. She explained that these stressors contribute to maternal mental health conditions, which often go underreported, undiagnosed, or misdiagnosed. Garland McKinney said that Black women and birthing people are more likely to experience societal judgment and increased provider judgment, which makes them less willing to seek help and receive care. Furthermore, she said that when seeking care, Black women face challenges such as providers who are less likely to provide detailed health care resources and less likely to honor requests for support.

Garland McKinney explained that primary sources of support that have been shown to mitigate maternal mental health symptoms for Black women include social connections such as co-parent partnerships, friendship networks, and faith communities as well as positive experiences with health care providers. She said that Black women and birthing people of color are more likely than others to cope with issues or complications independently due to negative interactions with providers. Doulas provide an important support system for Black women and birthing people of color by helping create positive perinatal experiences. At the core of this work are building trusting relationships with clients and advocating for clients in health care settings, she said.

During the panel discussion, two doulas, Adaeze Okoroajuzie of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and Octavia Smith of Mamatoto Village, offered insights into their work and the positive impacts that this work has on maternal mental health. Okoroajuzie and Smith emphasized that relationship-building underpins their work as doulas, both with their clients directly throughout the perinatal period and also between the client and hospital or other birth setting. Smith said that Mamatoto Village’s services support clients across multiple areas to make sure that mothers are prepared for childbirth through education, lactation support, and post-partum support and are focused on their emotional well-being. Okoroajuzie said that hospital rules can sometimes pose a challenge for doulas in supporting their clients. She explained that some hospitals do not exclude doulas from the limit on additional people allowed in the birthing room, which “creates a dynamic where I would have to step in and step out,” which in turn can affect the experience of the birthing person.

___________________

3 Kozhimannil, K. B., C. M. Trinacty, A. B. Busch, H. A. Huskamp, and A. S. Adams. 2011. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum depression care among low-income women. Psychiatric Services 62(6):619-625; Taylor, J., and C. M. Gamble. 2017. Suffering in silence: Mood disorders among pregnant and postpartum women of color. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/suffering-in-silence/ (accessed October 11, 2024).

4 Hoyert, D. L., and A. M. Miniño. 2020. Maternal mortality in the United States: changes in coding, publication, and data release, 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports 69(2).

Smith emphasized that doulas and maternal health care providers are united by a common goal: a healthy patient and a healthy baby. She said that, as part of supporting their clients, it is important for doulas to build a rapport with these hospitals and their staff. Both Okoroajuzie and Smith spoke about the need for hospital staff to have more education about the work of doulas. Okoroajuzie said that doulas may not be accepted in some health care settings, that health care providers should be educated about the important role doulas can play in supporting the pregnant person, and that health care providers should be informed about what doula training encompasses. Smith agreed and added that standards for doula training could help define the scope of practice and role of doulas.

COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANIZATIONS AND INNOVATIVE MODELS OF CARE

The second webinar focused on sources of support for historically marginalized pregnant women through community-based organizations (CBOs) and some of the innovative models of care used by CBOs. Natalie D. Hernandez-Green of Morehouse School of Medicine described a promising intervention in Georgia, where maternal health outcomes are among the worst in the United States. “More than half of our counties [in Georgia] are maternity care deserts,” she said, and that those maternity care deserts occur most often in the state’s Black communities. Hernandez-Green explained that, in developing interventions to address the gaps in care, the Morehouse School of Medicine Center for Maternal Health Equity focuses on research, community engagement, and training opportunities. She highlighted one “community-informed and -based model” the center has developed: the Community-Based Perinatal Patient Navigator Training program.5

Hernandez-Green said that there has been a significant amount of research around patient navigation as it relates to cancer care, “but we weren’t seeing a lot of models done in maternal health and specifically with laypeople.” The Community-Based Perinatal Patient Navigator Training program trains individuals in coordinating care, enhancing access to care, promoting self-efficacy and sustained engagement with care for pregnant and postpartum patients and features a rigorous curriculum. Additionally, navigators have access to training experiences with multi-disciplinary professionals, “we train our navigators as community health workers, as community-based doulas, as patient navigators and lactation peer support.” Hernandez-Green reported that the program has shown positive outcomes, with navigators assisting 157 mothers in less than 1 year, and that the care that coordination navigators provide goes beyond health care to include addressing unmet needs such as housing, food insecurity, transportation, income assistance, and more.

Emilia Iwu of Rutgers University discussed global perspectives on community midwifery care. Her presentation focused on a study that is part of the EQUAL (Ensuring Quality Access and Learning for Mothers and Newborns in Conflict-Affected Contexts) Consortium, which is focused on reducing global maternal deaths to less than 7 per 100,000 live births. Iwu provided an overview of maternal and newborn health in Nigeria, where the study is based, noting challenges such as a health worker shortage and high maternal mortality, with 1,047 deaths per 100,000 live births.6 She added that more than 50 percent of births in the country are home births, so women are delivering at home sometimes with unskilled providers. Iwu said that community midwifery, a strategy endorsed by the World Health Organization and other international bodies, can increase access to essential services in areas where trained birth attendants are not readily available, such as rural areas. The study also focuses on the effects of conflict on midwifery education in northeastern Nigeria and access to care. Iwu explained that armed conflict disrupts access to essential maternal health care for women in several ways, including the displacement of health care workers and the destruction of medical facilities, which means “pregnant women have to travel far in order to get services and, because of that, many of them are helped with their deliveries by unskilled birth attendants, which is also contributing to maternal mortality.” The midwifery education program assessment revealed such challenges as overburdened

___________________

5 For more information see https://centerformaternalhealthequity.org/programs/perinatal-patient-navigator-training-program (accessed October 11, 2024).

6 https://www.joghr.org/article/88917-closing-the-gap-in-maternal-health-access-and-quality-through-targeted-investments-in-low-resource-settings (accessed October 11, 2024).

classrooms and a lack of recommended hours of clinical practice experience, Iwu said. She added that working in collaboration with local governments is critical to improving midwifery education.

Brandi Desjolais of Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science described several innovative models for promoting birth equity. The Black Maternal Health Center of Excellence (BMHCE)7 at the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science is focused on improving birth outcomes and experiences while addressing structural racism as a root cause of disparity. Desjolais said that structural racism impacts maternal and infant mortality and that it is important for interventions to employ an anti-racism and a social determinants of health lens to maximize effectiveness. She said that interventions focused on reducing maternal stress experienced by Black women can improve birth outcomes. Desjolais explained that cultural concordance between providers and patients refers to a provider’s demonstrated ability to deliver high-quality, culturally and linguistically effective care to the specific population served and that building cultural concordance is an important strategy.

Desjolais described four examples of community-based models of care that are being studied:

- Guaranteed basic income (GBI), which she said has been shown to reduce poverty rates. Desjolais highlighted the Abundant Birth Project in California, which is testing GBI specifically for pregnant women to reduce maternal stress and improve birth outcomes.

- Group prenatal care, which “improves upon the traditional prenatal care model by cohorting women and adding a group session to discuss pregnancy health” in addition to standard physical health assessments. She added that the BMHCE provides free group prenatal care for cohorts of Black women in Los Angeles through funding support from the Department of Public Health and the California Perinatal Equity Initiative.

- Maternity homes, which are “usually residential homes where pregnant women live and receive services and support from staff with the goal of increasing housing stability and access to care.”

- Perinatal medical homes, which are an “evidence-based model that is designed to provide comprehensive patient-centered health care, using collaborative care teams.”

During the discussion session at the end of the webinar, several speakers referred to the need for systemic change and collaborative efforts. Hernandez-Green said that there are persistent myths about the role that individuals or those who are not experts can contribute to people’s birthing experiences, and Desjolais said awareness and education early in medical education about the work of community-based providers, including doulas, is key. Offering closing remarks on the collaborative and expansive nature of midwifer, Cat Dymond of the Atlanta Birth Center said that “midwives champion health” and emphasized the importance of collaboration within health care teams across models of birthing care.

OUTCOME STUDIES OF MATERNAL HEALTH CARE AND DISPARITIES WITHIN ACTIVE-DUTY SERVICE

The third webinar explored findings from studies on maternal health outcomes and disparities in care among women in active-duty service in the U.S. military. Speakers discussed study findings illustrating the unique challenges for maternal health care in the military service and the disparities that exist. In opening remarks, Julie Pavlin of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine referred to her own experience as an Army Medical Corps officer and said that although the military health system is free for active-duty service members to use, many face barriers to accessing care that may result in disparities in health outcomes.

Tracey Perez Koehlmoos of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences opened the panel with an overview of the military health system (MHS) and racial disparities. The MHS serves 9.6 million beneficiaries,8 approximately 1.4 million of whom are on active duty, through two systems of care: direct care and TRICARE health insurance. Koehlmoos said that her research9 team

___________________

7 See https://www.bmhce.org/ (accessed October 11, 2024).

8 For more information see https://www.health.mil/About-MHS (accesssed October 11, 2024).

9 Koehlmoos, T. P., J. Korona-Bailey, M. L. Janvrin, and C. Madsen. 2022. Racial disparities in the military health system: A framework synthesis. Mil Med. 187(9-10):e1114-e1121. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usab506.

recognized early on that they were not seeing the same magnitude of differences based on race that they would have expected to see in the broader U.S. population and suspected that this was related to the MHS providing universal health care with no or very low co-payments. Koehlmoos described a framework synthesis of studies that found “in women’s health, our direct care closed system—where most of our active-duty people receive care—was doing a wonderful job or a better job of mitigating racial disparities” compared with the U.S. health care system overall, particularly in specific areas such as surgery and screening. Koehlmoos said that while many disparities are mitigated in the MHS, “there’s miles to go before we rest.” She said additional efforts are focused on developing a more comprehensive systematic review of racial disparities and studying patient–provider racial concordance.

Lynette Hamlin, also of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences provided an overview of findings from a study, conducted by herself and her team, which was designed to determine the prevalence of adverse perinatal outcomes among U.S. active-duty service women and determine if there were racial or socioeconomic disparities in these outcomes among this population. The study defined adverse perinatal outcome as a negative change in the health status of the mother or fetus between 22 weeks of gestation and 7 days postpartum, and it assessed such outcomes as low birthweight, postpartum hemorrhage, high-risk pregnancy, and Caesarean birth rates. There are several commonalities across the population studied, Hamlin said, noting that all active-duty service women have the same pay as others of their rank and have universal health coverage through the MHS. The study assessed 128,666 deliveries among 84,319 patients, Hamlin said, and found that Black active-duty service women experienced higher rates of adverse perinatal outcomes than their White counterparts. Thus, in spite of universal insurance, universal access, and a generally healthy state going into pregnancy, Black active-duty service women experience the same national crisis of increased risk for adverse maternal outcomes. In addition, junior officers were at higher risk for adverse outcomes. Hamlin recommended further research on the social determinants of health, access to equitable provision of guideline-concordant care, and examination of clinical practice guidelines in MHS hospitals.

Capt. Monica A. Lutgendorf of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences discussed qualitative analyses of reproductive health care experiences within the MHS. She said that there are persistent disparities in maternal health outcomes for service members and spouses receiving maternal care through the MHS, with historically marginalized populations experiencing higher rates of pregnancy-related complications. Lutgendorf described outcomes of a qualitative study10 to investigate how military life and the use of health care systems interact with the sociocultural aspects of service to affect how service members and their families experience perinatal care. The study included interviews with active-duty military members and family members and revealed participants’ concerns across several themes, including the effects of pregnancy on career advancement and challenges navigating health care. Lutgendorf said that participants also expressed concerns regarding mental health care, including some challenges with seeking mental health care where providers minimized symptoms or did not take action. She added that “participants also reported feeling abandoned postpartum and that their health was no longer a priority.” Several recommendations for improvement were offered by participants, Lutgendorf said, including offering regular mental health care check-ins during pregnancy and post-partum and highlighting the importance of support groups and doulas. In closing, Lutgendorf said that military service is a social determinant of health with unique challenges and privacy concerns and that perinatal mental health care is essential to postpartum health care.

Lt. Col. Gayle Haischer-Rollo of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences presented findings from a study on the role of institutional and interpersonal racism on maternal–child health outcomes in the MHS. She noted that conducting research within the MHS allowed researchers to control for socioeconomic status and

___________________

10 Musilli, M. G., S. M. Fuller, B. Wyatt, T. R. Ryals, G. Haischer-Rollo, C. M. Drumm, R. J. Vereen, T. C. Plowden, E. M. Blevins, C. N. Spalding, A. Konopasky, and M. A. Lutgendorf. 2024. Qualitative analysis of the lived experience of reproductive and pediatric health care in the military health care system. Military Medicine usae238. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usae238.

access to health care. The data show a two-fold higher rate of perinatal death for Black non-Hispanic people in the MHS, she said, adding that this led researchers to investigate the effect of oppressive medical care, or “lack of autonomy, . . .racism, sexism, homophobia, nativism, and religious bias that leads to a decrease in health care outcomes.” Haischer-Rollo said that the practice of cultural humility—which she defined as a lifelong process for those who are taking care of patients in reflection and self-critique that deliberately acknowledges the existence of multiple social statuses, intersectional identities, and things that shape beliefs for patients that interact with their health care—can offer insights on strategies for improvement. The study employed qualitative interviews with service members of different ethnicities and ranks who had given birth in the MHS within the past 5 years. The results of this effort revealed a lack of cultural humility from the healthcare team which centered around poor communication, lack of autonomy, and judgment, she said. Haischer-Rollo said that it is critical for the MHS to develop a unified approach to address cultural humility in order to improve outcomes for patients.

During the discussion session, several speakers noted that there are barriers to accessing care in the MHS despite universal coverage. Koehlmoos said that scheduling appointments can be a challenge and that the needs of a service member’s unit may affect that member’s decision to go to appointments. Haischer-Rollo emphasized the need for greater diversity among the health care workforce within the MHS.

UNDERSTANDING MICROAGGRESSION AND IMPLICIT BIAS AWARENESS

The fourth webinar in the series explored the importance of expanding awareness of microaggression and implicit bias among maternal health care providers and educators. In opening remarks, Wanda Barfield of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spoke about the critical issue of maternal mortality in the United States, emphasizing that most pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are preventable and disproportionately affect women from historically marginalized populations. She stressed the importance of respectful maternity care, noting that implicit bias and microaggression can not only affect the quality of care, but can also reduce a birthing person’s trust and interest in seeking further care.

Moderator Diane Young of the Prince George’s County, Maryland, Health Department explained that implicit bias and microaggression can result in unequal treatment and adverse health outcomes and provided definitions to frame the discussion:

- “Implicit bias refers to the unconscious attitudes and stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decision making.”

- “Microaggression refers to subtle behavioral and environmental slights that express prejudice or discrimination toward a member of a marginalized group, such as a racial minority.”

Janice Sabin of the University of Washington spoke about the history of racism in medicine and the contribution of implicit bias and microaggression to maternal health disparities.11 She highlighted global disparities in maternal mortality, noting that the United States ranks 64th in maternal mortality among 186 nations, with 21 deaths per 100,000 live births.12 She said that CDC data show drastically higher mortality rates among non-Hispanic Black and Indigenous pregnant women compared to White pregnant women in the United States, framing it as a public health and equity crisis. Sabin said that current disparities are influenced by a history of racism in medicine and that many false beliefs developed in the past persist today and may influence modern health care practices.

In reference to the impact and occurrence of microaggression in health care, Sabin referred to research investigating mistreatment in childbirth. One study13 found that African American women who experience microag-

___________________

11 Montalmant, K. E., and A. K. Ettinger. 2023. The racial disparities in maternal mortality and impact of structural racism and implicit racial bias on pregnant black women: A review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities November. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01816-x; Saluja, B., and Z. Bryant. 2021. How implicit bias contributes to racial disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 30(2):270-273. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8874.

12 https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/maternal-mortality-ratio/country-comparison (accessed October 11, 2024).

13 Vedam, S., K. Stoll, T. K. Taiwo, N. Rubashkin, M. Cheyney, N. Strauss, M. McLemore, E. Nethery, E. Rushton, L. Schummers, E. Declercq, and the GVtM-US Steering Council. 2019. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health 16(1):77. https://doi.org.10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2.

gression may delay the use of prenatal care, and another found that 17.3 percent of pregnant women reported mistreatment characterized by a loss of autonomy, being shouted at, being scolded, and being threatened, being ignored, or not being responded to when asking for help, with higher rates among women of color and those of lower socioeconomic status.

She said that implicit bias—which can manifest in snap judgments and automatic associations—is difficult to address but significantly affects patient experiences. A study focused on clinic visits found that clinicians’ “implicit pro-White bias …impacted patient experience,” Sabin said. She also noted research14 indicating that implicit bias can be “contagious” and that observing biased behavior can increase the observer’s bias. Sabin said the study also indicated that positive behaviors can be spread similarly. To combat implicit bias and microaggression in health care, Sabin proposed several strategies, including increasing personal awareness, data monitoring, reducing discretion in decision making, promoting diverse workforces, partnering with communities, and establishing accountability.

Mary Owen of the University of Minnesota Medical School emphasized the importance of focusing on community strengths rather than solely on negative statistics when discussing maternal health care in Indigenous communities. Owen highlighted the critical role of doulas, naming the Alaska Native Birthworkers Community in particular, as advocates for patients and building “relationships that are so critical in maternal health.” Owen said that invisibility is the most important consequence of centuries of erasure and is perpetuated by microaggression and racism. This invisibility manifests as a lack of access to adequate health care, housing, and education, she said, as well as a lack of representation in health care and research. Owen explained that microaggressions, including assumptions, impatience, and denial of experiences, have a significant negative impact of patients’ engagement with health care and contribute to long-term mistrust.

Owen provided an overview of a 2023 report15 by the Advisory Committee on Infant and Maternal Mortality, which outlines strategies to improve health and safety for American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) mothers and infants. Owen said that the committee met with Indigenous communities to “help inform what should be the recommendations on how to… lessen disparities” these groups face in health and safety. She added that the key recommendations made by the committee included prioritizing AIAN maternal and infant health by addressing data invisibility and engaging community leaders in decision-making, expanding federal programs like Healthy Start and the Healthy Native Babies Project, improving living conditions and ensuring universal access to high-quality health care by fully funding the Indian Health Service, and addressing urgent challenges affecting AIAN women. These challenges include “recognizing the impact of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls” and improving care for incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women, Owen said. She also noted the need for expanded mental health and intimate partner violence screenings.

During the discussion session, speakers touched on the role of institutional bias in maternal health disparities. Owen emphasized the importance of measuring outcomes for all populations and Sabin added that individuals have power to effect change in their institutions. Sabin said it is key to examine systems, such as electronic health records, noting that “historical racist beliefs could be potentially embedded” in these systems and so perpetuate bias. Several speakers emphasized the importance of recognizing unintentional bias and looking at outcomes to drive change. Sabin said that her institution implemented a bias reporting system to help create transparency around reporting. To encourage self-reflection without defensiveness, Owen cautioned against labeling patients and emphasized collective responsibility. Speakers were asked about the intersectionality of racial and class biases and Owen said education must include discussions of both racial and class bias. In response to a question about strategies to train health care workers

___________________

14 Willard, G., J. K. Isaac, and D. R. Carney. 2015. Some evidence for the nonverbal contagion of racial bias. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 128:96-107.

15 For more information, see https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/infant-mortality/birth-outcomes-AI-AN-mothers-infants.pdf (accessed October 11, 2024).

to prevent microaggression and bias, Sabin suggested teaching patient-centered communication skills.

BUILDING TRUST IN HEALTH CARE AMONG HISTORICALLY MARGINALIZED PREGNANT WOMEN

Yvette Roubideaux of the Colorado School of Public Health opened the final webinar by emphasizing the critical role that trust plays in health care. Roubideaux said that lack of trust in health care is a significant issue generally, but it is particularly an issue among historically marginalized populations, and it is critical to address in order to find solutions to persistent maternal health disparities. Moderator Niraj Chavan of the Saint Louis University School of Medicine said that trust is an essential component of health care and key to the patient–physician relationship. He noted that recent surveys indicate a significant decline in trust in health care, and he emphasized that “experiences of discrimination and neglect that our patients encounter have a long-lasting impact” on their future decisions about seeking care.

To begin the panel discussion, Chavan asked the speakers to offer insights on understanding trust in health care. Carla S. Alvarado of the Association of American Medical Colleges emphasized that trust must be earned through community inclusion and following through on commitments. Noelene K. Jeffers of the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing added that trust is an expectation that health care providers will act in patients’ best interests, emphasizing that trust can “mean the difference between deciding to seek care or delaying treatment.” Maria J. Romo-Palafox of the Saint Louis University stressed the importance of valuing each patient as an individual with the right to make decisions and supporting patients in making their decisions, ensuring that their choices are informed choices. Jules Javernick of Regis University said that trust is built over a series of encounters, not in a single visit. She highlighted “a nonjudgmental, authentic approach,” empathy, acknowledging patient concerns, and focusing on the idea of “power with rather than power over” as key elements of building trust. Lucinda Canty of the University of Massachusetts Amherst emphasized the importance of understanding patients’ experiences of care and establishing mutually respectful relationships. She added that communication is key to maintaining trust and that providers must remember, “the way that we show up in that health care visit really dictates that experience of care.”

Ayesha Jaco of the West Side United spoke about trust-building strategies in the context of working with diverse communities. Jaco explained that West Side United focuses on addressing Chicago’s life expectancy gap. She emphasized the need to acknowledge structural racism, historical disinvestment, and the social drivers of inequities. Jaco said that it is critical for organizations to have “presence, consistency, and long-term investments” in the communities they serve. Jaco emphasized that negative health care experiences can potentially deter individuals from seeking necessary care in the future.

The panel next discussed education and training strategies to promote trust-building. Canty emphasized teaching students to look beyond race and social conditions to understand the individual “needs of that person when they show up for care in front of us.” Javernick said that using reflective practices in clinical courses can help give students the tools to become “empathetic, respectful caregivers.” Jeffers emphasized that educational programs should model trust with students, noting a study where Black students reported mistrust in their midwifery education programs. Romo-Palafox said that removing barriers to health care education can help build a more diverse workforce. She suggested creating pathways that do not require unpaid internships. Chavan said that trust-building discussions should be woven into clinical education, even informally. He also emphasized the importance of incorporating non-physician provider roles in educational efforts.

In the final portion of the panel discussion, speakers shared strategies for health systems to develop trust with the communities they serve. Jaco said it is critical for health systems to meet communities where they are. Canty emphasized that health care providers must be taught to work in the community, highlighting the importance of understanding the context of patients’ lives beyond the clinical setting. Romo-Palafox added that working with communities connects health care providers to the real-world implications of their work. Jeffers said that health care providers do not hold all the

expertise and knowledge concerning health, emphasizing that communities possess valuable health knowledge.

During summary remarks on the panelists’ discussions, Alvarado said that it is crucial to “reckon with the fact that the health care system has, engendered mistrust and distrust” among patients. Alvarado highlighted the need for teaching students self-inquiry and reflection with the cornerstones of dignity and respect. She also noted how shifting the types of skills valued in health care education could help build trusted relationships, highlighting the fact that both technical and soft skills are needed in clinical settings.

Karen McDonnell closed the webinar series by stating, “Only by strengthening relationships within the maternal health ecosystem can we strive to ensure that all women receive the care and support they need to have safe pregnancies and childbirth experiences ultimately improving the health and well-being of mothers and communities alike.”

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief has been prepared by Jamie Durana as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteur or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

COMMITTEE MEMBERS Claire Brindis (Chair), University of California, San Francisco; Andreia Alexander, Indiana University School of Medicine; Elizabeth Ananat, Barnard College, Columbia University and National Bureau of Economic Research; Wanda Barfield (ex officio Member), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Bruce N. Calonge, Colorado School of Public Health; Alison N. Cernich (ex officio Member), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Judy Chang, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Ellen Wright Clayton, Vanderbilt University; Cat Dymond, Atlanta Birth Center; Michelle Bratcher Goodwin, Georgetown University School of Law; Barbara J. Grosz, Harvard University; Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing; Lisa Harris, University of Michigan; Justin R. Lappen, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine; Monica McLemore, University of Washington School of Nursing and School of Public Health; Rebecca R. Richards-Kortum, Rice University; Sara Rosenbaum, George Washington University; Yvette Roubideaux, Colorado School of Public Health; Alina Salganicoff, KFF; Susan C. Scrimshaw, University of Illinois at Chicago; LeKara Simmons, AMAZE; Melissa Simon, Northwestern University; Lisa Simpson, AcademyHealth; Tracy A. Weitz, American University and Center for American Progress; Katherine L. Wisner, Children’s National Hospital and George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

*The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief rests with the institution. Planning committee members: Karen A. McDonnell, The George Washington University; Jasmine L. Garland McKinney, The University of Maryland at College Park; Brandi Desjolais, Charles R Drew University of Medicine and Science; Lynette Hamlin, Uniformed Services University; Mary Owen, University of Minnesota Medical School; Emilia Iwu, Rutgers School of Nursing; Natalie Hernandez, Morehouse School of Medicine; Tiffany Green, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Sabrina Salvant, American Occupational Therapy Association; and Joanne Goldbort, Michigan State University. The planning committee emanated from activities supported by the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education chaired by Zohray Talib, California University of Science and Medicine, and Jody Frost, consultant. For the full Global Forum roster please visit: https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/global-forum-on-innovation-in-health-professional-education.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop Series—in Brief was reviewed by Karen McDonnell, George Washington University, Meagan Robinson Maynor, Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs, and Pamela Stratton, National Institutions of Health. Leslie Sim, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS This workshop series was supported by the National Academy of Sciences W.K. Kellogg Foundation Fund and the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education. The Global Forum is supported by contracts with National Academy of Sciences and Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, American Academy of Nursing, American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, American Board of Family Medicine, American Council of Academic Physical Therapy, American Dental Education Association, American Medical Association, American Nurses Credentialing Center, American Occupational Therapy Association, American Physical Therapy Association, American Psychological Association, American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Association of American Medical Colleges, Association of Schools and Colleges of Optometry, Athletic Training Strategic Alliance, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Council on Social Work Education, Intealth, Massachusetts General Hospital Institute of Health Professions, National Academies of Practice, National Association of Social Workers, National Board for Certified Counselors and Affiliates, National Board of Medical Examiners, National Council of State Boards of Nursing, National League for Nursing, National Register of Health Service Psychologists, Physician Assistant Education Association, Society for Simulation in Healthcare, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Uniformed Services University, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and Weill Cornell Medicine—Qatar.

STAFF Patricia Cuff, Senior Program Officer; Erika Chow, Research Associate; Julie Pavlin, Senior Board Director; Ashley Bear, Board Director; Natacha Blain, Senior Board Director; Priyanka Nalamada, Program Officer; Laura DeStefano, Director of Strategic Communications & Engagement; Melissa Laitner, Senior Program Officer, Special Assistant to the President; Adaeze Okoroajuzie, Senior Program Assistant; Kavita Shah Arora, Consultant.

For additional information regarding the workshop series, visit http://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/standing-committee-on-reproductive-health-equity-and-society.

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. Considering maternal health disparities: Proceedings of a workshop series—in brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/28038.

| Health and Medicine Division Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Academy of Medicine Policy Global Affairs Copyright 2024 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|