Advancing Equity in Diagnostic Excellence to Reduce Health Disparities: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2025)

Chapter: Advancing Equity in Diagnostic Excellence to Reduce Health Disparities: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

|

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief |

Convened September 23–24, 2024

Advancing Equity in Diagnostic Excellence to Reduce Health Disparities

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

To explore opportunities for improving equitable diagnosis to reduce health disparities in the United States, the Forum on Advancing Diagnostic Excellence at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a hybrid public workshop in collaboration with the Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity on September 23–24, 2024, with support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).1 The workshop highlighted factors contributing to diagnostic inequities and suggested potential strategies to advance health equity through technology, education, research, and patient- and community-centered approaches.2 Kathryn McDonald from Johns Hopkins University said, “Advancing diagnostic equity is not merely about providing equal access to health care. It’s about ensuring that every person has the opportunity to receive the accurate diagnosis that they deserve, recognizing and dismantling the barriers that prevent equitable care, and committing ourselves to a health care system . . . that serves everyone with the respect that they deserve.” Karen Cosby of AHRQ’s Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety noted that 800,000 individuals either die or suffer permanent harm each year from diagnostic errors (Newman-Toker et al., 2024). She said some people bear a disproportionate burden of harm and said, “We need to understand that due to no fault of their own, simply by who they are or where they live, people suffer preventable harm.” This workshop builds on the consensus report Improving Diagnosis in Health Care (NASEM, 2015) and a workshop series on Advancing Diagnostic Excellence.3 This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief highlights the presentations and discussions that occurred at the workshop.4

PATIENT, CAREGIVER, AND COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVES

Candace Henley, founder and chief surviving officer at the Blue Hat Foundation, discussed her misdiagnosis with colorectal cancer and suggested ways for clinicians to improve the diagnostic experience for patients. When she was experiencing symptoms of colorectal cancer at age 35, she said that her age played a role in her misdiagnosis because her symptoms were not taken seriously. She

__________________

1 This publication is derived from work supported under a contract with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) contract #75Q80124P00003. However, this publication has not been approved by the agency.

2 The workshop agenda and presentations are available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/43298_09-2024_advancing-equity-in-diagnostic-excellence-to-reduce-health-disparities-a-workshop (accessed November 21, 2024).

3 More information is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/advancing-diagnostic-excellence-a-workshop-series (accessed November 21, 2024).

4 This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief is not intended to provide a comprehensive summary of information shared during the workshop. The information summarized here reflects the knowledge and opinions of the individual workshop participants and should not be seen as a consensus of the workshop participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

added that “[clinicians] went directly to ‘it is female-related,’” noting her history of endometriosis and fibroid tumors. Reflecting on her misdiagnosis and experience of not understanding medical terminology used by clinicians, Henley emphasized the importance of clinicians discussing family history with patients and communicating clearly to ensure patients understand their diagnosis and treatment. In addition, Henley highlighted the need for clinicians to tailor treatment options to match a patient’s lifestyle and consider responsibilities that may include work or caregiving for children. To bridge the divide between clinicians and patients, Henley suggested open, empathetic communication from clinicians. Finally, while disparities occur at every step of the diagnostic process, gaps in access and follow-up are especially challenging. “What we fail to acknowledge is that our health system was never designed to be equitable in the first place,” she concluded.

Yadira Montoya, programs director for the National Alliance for Caregiving, described the growing prevalence of the caregiver role in the United States. There were 53 million caregivers in 2020, she said, making one in every five people a caregiver.5 Caregivers provide emotional support, logistical support (e.g., transportation), care coordination, and patient advocacy, and Latino and African American caregivers are especially overburdened, she said. Montoya noted that recent policy changes have recognized the role of caregivers. For example, Medicare reimbursement enables clinicians to provide caregiver training services directly to the caregivers of their patients. Montoya said that documentation of caregivers is required for patients to get on an organ transplant wait list, which can lead to substantial gaps in diagnosis or treatment if the health care system does not recognize who is serving as a caregiver. Montoya emphasized the importance of recognizing caregivers, integrating them into the health care team, and providing them with education and support. Educated caregivers can also be allies with clinicians, she noted, helping patients better understand their diagnosis and treatment.

Guillermo Chacón, president of the Latino Commission on AIDS, spoke about diagnostic challenges in Hispanic and Latino communities. First, it is important to recognize that the Hispanic community is not a singular identity but is composed of multiple cultures and histories from South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Indigenous nations, he said. Chacón explained that his organization works with these communities to understand their perspectives. He highlighted the need for partnerships with community-based organizations, like developing health ministries through churches that can provide health promotion and education to better engage with communities and reduce health disparities. Chacón also noted that health care challenges in the United States are compounded by the fragmented nature of the health care system and because 17–19 percent of people do not have health care access nationwide. Another barrier to high-quality diagnoses, he mentioned, is the need to further validate statewide health, social, and economic data on the people being diagnosed.

EXAMPLES OF DIAGNOSTIC DISPARITIES ACROSS CLINICAL CONDITIONS

Deeonna Farr, assistant professor at East Carolina University, discussed the factors contributing to diagnostic delays in breast and colorectal cancer. When discussing the breast cancer screening process, Farr emphasized the importance of timeliness in diagnostic resolution (i.e., concluding if results are benign or malignant). The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program suggests that 75 percent of a screening population should reach diagnostic resolution within 60 days (Caplan et al., 2000), and a diagnosis that takes more than 90 days is associated with worse cancer outcomes (Doubeni et al., 2018). Farr described several factors that can influence breast cancer diagnostic delay, such as insurance status at the patient level, procedure volume at the health care system level, and transportation access at the community level. Farr and her colleagues (2024) used the Carolina Mammography Registry to analyze data on 25,114 women with abnormal mammograms between 2011 and 2019. They found that for abnormal screening mammograms, non-Hispanic Black women and Hispanic/Latina women showed longer resolution times and were less likely to get resolution within 60 days compared to White women. Timely diagnostic resolution is also important for colorectal cancer, which has lower

__________________

5 See https://www.aarp.org/pri/topics/ltss/family-caregiving/caregiving-in-the-united-states/ (accessed December 15, 2024).

resolution rates compared to breast cancer, Farr added. An optimal completion interval is 90 days for colorectal cancer, and risk of a poor outcome increases after 180 days, she said. Farr identified contributors to diagnostic delay, which include fear of cancer diagnosis and medical procedures, aversion to bowel prep, and cost concerns. To mitigate breast cancer delays, Farr suggested collecting data from imaging centers that are actively screening populations rather than retrospective data and discussed the need to better understand clinical barriers to timely resolution. Farr suggested more research on intervention strategies that can be paired with patient navigation to reduce delays in colorectal cancer follow-up as well as ways to optimize strategies in different contexts, including rural areas.

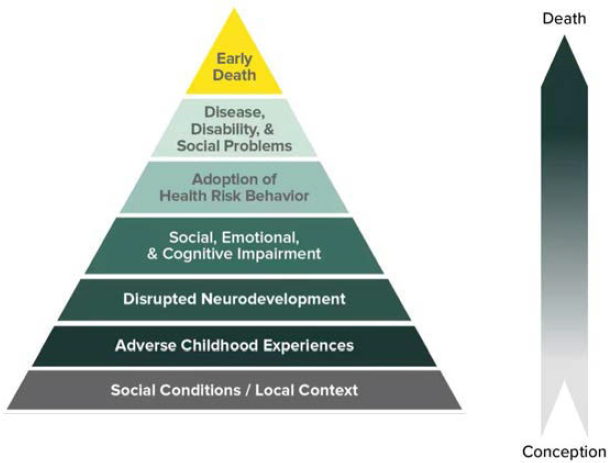

Cristiane Duarte, professor at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute, discussed several factors that contribute to mental health inequities in children. In this developmental stage, racial and ethnic inequities in mental health disorders can be best understood by focusing on contextual and environmental factors, which are key for understanding where the risk stems from, said Duarte. When adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, Olfson and colleagues (2023) found that racial and ethnic disparities in mental health disorders were no longer statistically significant. The study found that children from families with low incomes were associated with elevated odds of having a mental health disorder. Duarte highlighted how utilization of services can contribute to disparities; Black and Latino children were less likely to use mental health services compared to White children due to challenges with affordable and accessible mental health care (Rodgers et al., 2022). Duarte’s longitudinal work focused on Puerto Rican children and young adults further illustrate that environment and early childhood experiences can be bigger risk factors for mental health disorders even within the same racial subgroup. The Boricua Youth Study6 found higher rates of depression and anxiety in young adult women, and higher levels of substance use in young women and men in the South Bronx compared to those in San Juan. Adverse Child Experiences (ACEs) are associated with negative health outcomes and risk for various health conditions and diseases (Figure 1). Duarte and her team considered how ACEs could impact the higher prevalence of mental health disorders in the South Bronx and San Juan populations and found that maltreatment and neglect, exposure to violence, parental loss, and parental maladjustment were associated with risk for mental health conditions, sleep problems, lower or delayed pubertal development, sensation seeking, and higher risk for suicide ideation and attempts. Duarte’s research also identified some factors that could be protective and increase resilience, and she said that familism or “what values [study participants] have, how much they value the experience of being with family, having a family be together and help each other at times of need . . . were related to lower risk of antisocial behaviors among girls ages 10 to 13.”

Sadiya Khan, associate professor and cardiologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, discussed diagnostic disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is the leading cause of death in the United States. Several multilevel barriers contribute to diagnostic inequity in CVD and subsequent outcomes, including historical marginalization, sex and gender disparities, and lower income and education level. Khan said, “the burden of cardiovascular disease is substantial and increasing, and significant disparities due to individual, interpersonal, and structural drivers exist.” Khan

SOURCES: Presented by Cristiane Duarte, September 23, 2024. Figure adapted by CDC. See https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html (accessed March 14, 2025).

__________________

6 The Boricua Youth Study is a longitudinal two-site cohort study that began in 2001 that tracks the psychopathology of children of Puerto Rican descent living in the South Bronx, New York, and San Juan, Puerto Rico. See: https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/research-labs/child-mental-health-disparities-and-development-group (accessed January 3, 2025).

discussed place-based disparities by illustrating how the geographic distribution showing higher social vulnerability (i.e., socioeconomic and demographic factors such as poverty, crowded housing, and community-level stressors) was associated with higher rates of obesity and coronary heart disease in Chicago. Historically marginalized populations are also likely to face diagnostic inequities due to greater barriers in access to health care due to cost, and insurance coverage denials of routine preventive care. “Sex and gender disparities are also very apparent in cardiovascular disease,” said Khan, noting the gap in studying, diagnosing, and treating cardiovascular disease in women, and “sex-specific risk factors such as adverse pregnancy outcomes and premature menopause that uniquely influence women and their interaction with the health care system.” Khan said clinician bias can also affect the provision of timely and accurate diagnostic care for acute cardiovascular conditions, highlighting a study that found physicians were less likely to refer women and Black patients for cardiac catheterization (Schulman et al., 1999). Khan suggested multilevel opportunities to pursue diagnostic equity in CVD, including bias training for clinicians and health system administrators, systematic assessment and management of social determinants of health (SDOH), increased public awareness of symptoms of CVD, and increased access to high-quality patient-centered holistic care.

EXAMPLES OF DIAGNOSTIC INEQUITIES AMONG HIGH-RISK POPULATIONS

Jason Deen, associate professor at the University of Washington and Blackfeet Nation member, discussed how systemic issues, historical traumas, and current economic, political, and social contexts continue to affect health inequities in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. These Indigenous populations in the United States have a lower life expectancy and higher mortality rates caused by chronic illnesses, such as heart diseases and cancers as well as accidents and alcohol-related deaths compared to other populations (IHS, 2019). Deen noted the Indian Health Service (IHS) is the largest provider of health care for American Indians and Alaska Natives but is poorly funded compared to other federally supported programs, creating challenging conditions for health service delivery including diagnostic care. Historical trauma from colonization that disrupted traditional health systems in communities, tribes, and nations; forced removal from home territories and displacement; centuries of violence and warfare; disease outbreaks; and forced assimilation continue to contribute to poor health outcomes in Indigenous communities, Deen said. He also described the legacy of federal assimilatory boarding schools7 that led to loss of the traditional family unit, loss of culture, psychological and physical abuse, and adverse childhood experiences, which continue to be prevalent among children in Indigenous communities. Deen emphasized that, “acknowledging the traumatic history is a necessary first step, though truthfully addressing these health inequities requires systemic solutions, such as expanding educational opportunities for Native peoples.”

Veronica Gillispie-Bell, medical director of the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative, described factors that contribute to diagnostic inequities in Black women. Research indicates that people of color are less likely than White people to receive needed medical services and that underlying implicit bias affects the way clinicians deliver care. As an example, Gillispie-Bell cited a study showing that 50 percent of medical students believed that Black individuals were less sensitive to pain compared to White individuals, and the students were less likely to prescribe appropriate pain medication (Hoffman, et al., 2016). Gillispie-Bell said this is “another example of how that biased belief becomes a practice,” which directly affects approaches to diagnostic care and risk. After pointing out the removal of race from the calculator to more accurately predict the risk of vaginal birth after cesarean, she raised concerns about the inclusion of race in other health care algorithms and its potential impact on exacerbating inequities. Black Americans face systems- and community-level barriers such as lower socioeconomic

__________________

7 In 1819, the U.S. Senate allocated funds to support “an Act making provision for the civilization of the Indian tribes adjoining the frontier settlements” that built boarding schools and provided funding to existing schools and churches to assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children. Over 400 schools and institutions operated by the United States from 1819 to 1969 focused on educating children in vocational tasks, employed forced manual labor, discouraged the practice of Indigenous traditions and language, frequently used abuse and corporal punishment on children, and led to over 900 deaths. See https://www.doi.gov/priorities/strengthening-indian-country/federal-indian-boarding-school-initiative (accessed November 8, 2024); https://www.bia.gov/sites/default/files/dup/inline-files/bsi_investigative_report_may_2022_508.pdf (accessed November 8, 2024); and https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl/llsl-c15/llsl-c15.pdf (accessed November 8, 2024).

status and education, increased food insecurity, and lack of transportation; addressing all SDOH is important for mitigating these health inequities, said Gillispie-Bell. Programs that increase access to care, such as Connected Mom which provides Bluetooth-enabled blood pressure cuffs during pregnancy, have led to earlier diagnosis and the ability to track serious signs and symptoms of hypertension and preeclampsia. “We must implement change through a lens of equity,” concluded Gillispie-Bell, “and bring care to the patient instead of making the patient come to care.”

Karen Fredriksen-Goldsen, professor at the University of Washington, discussed “examining health inequities and disparities among sexual and gender minority (SGM) older adults,” noting that the population rates are increasing annually with projections of more than 5 million SGM adults over age 50 by the year 2060 (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017). Fredriksen-Goldsen shared data that showed SGM older adults had elevated rates of stroke, heart attack, asthma, cancer, and other conditions (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2017). Data from the Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS)8 found that many SGM older adults who seek health care underestimate their health risks and need for care, and they are more likely to utilize informal care and depend on their support partners and age-based peers, which Fredriksen-Goldsen explained can be a vulnerability when their peers are also contending with health challenges. SGM older adults with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease can end up especially isolated. Bias and discrimination remain barriers within the health system and in the patient-clinician relationship, as 25 percent of SGM adults have not told their clinician about their sexual identity or orientation. Fredriksen-Goldsen said 20 percent of SGM adults report they have been denied care due to their identity; denied care was especially prevalent among Black and Hispanic SGM older adults and those living in rural areas. She noted that these barriers can hinder patient–clinician communication and limit opportunities for tailored care. Reducing health disparities will involve examining systemic barriers to care, understanding the distinct risks of subgroups within the SGM community, developing culturally responsive interventions, and addressing explicit and implicit biases in care. To conclude, Fredriksen-Goldsen described two programs developed by her team to address the needs of SGM older adults: Innovations in Dementia Empowerment and Action and Safe Home.9

STRUCTURAL BARRIERS TO CARE ACCESS

Elizabeth Crouch, associate professor at the University of South Carolina, described challenges to accessing high-quality diagnosis in rural areas. Sixty percent of rural counties are designated health professional shortage areas, with a shortage of both primary care clinicians and specialist practitioners (Larson et al., 2020). Physical distance to facilities is an additional challenge for rural residents; for example, almost 20 percent of rural Americans live more than 60 miles from an oncologist (Hung et al., 2020). Hospital closures are more common in rural areas, as are obstetric unit closures affecting access to high-quality maternal care. Crouch said rural hospitals are more likely to serve high-cost, under- or uninsured patients, resulting in hospital budget shortfalls if they are not reimbursed by the state. Crouch explained that telehealth is often considered a solution to increasing access to diagnostic care, but rural residents are less likely to have access to broadband service and less likely to use telehealth for health care. “We often anecdotally hear about rural residents in our state, especially veterans, doing teletherapy in McDonald’s parking lots because that’s where they can access the Internet,” she said. Poverty is another barrier to care, Crouch said, and explained that patients who are publicly insured may be limited by the number of clinicians who accept their insurance. These challenges, she noted, are especially salient for people of color living in rural areas, who face a “dual barrier of the intersection of race and rurality.” Efforts to understand the barriers to accessing care are compounded by issues with rural datasets, such as varying definitions of “rural,” public use restrictions, and small sample sizes. Funding will be important to improve research in this area, she said, and constructing data sets that do not suppress rural data.

__________________

8 The Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS) is a federally funded, longitudinal study that includes over 2,400 participants who identify as a sexual or gender minority and are between the ages of 50 and 100. See https://goldseninstitute.org/health/nhas/ (accessed December 1, 2024).

9 For more information on the programs, see Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2018 and 2023.

Cecilia Canales, assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, addressed the role of language proficiency in accessing equitable diagnosis. Canales illustrated that poor communication is a common cause of errors in health care by describing an anecdote of a patient with high glucose levels who was labeled as non-adherent with diabetes treatment. Further communication with the patient revealed a misunderstanding during a previous visit when the glucose levels were well-controlled. A family member who was providing interpretation misunderstood the feedback, leading them to believe the patient no longer had diabetes and no longer needed to take medication. The framing of this was important, Canales said, because perceived noncompliance influences how clinicians view and approach patients. Furthermore, Canales emphasized “it is common for patients to be labeled as ‘non-compliant,’ when in fact ineffective communication and lack of comprehension of instructions result in diagnostic and treatment failure.” Patients who do not speak English often get excluded from studies on postoperative delirium or cognitive decline, contributing to disparities in research. In a study on preoperative cognitive screening, Canales and her colleagues found patients who spoke English were screened 89 percent of the time, while those who preferred other languages were screened just over 58 percent of the time (Canales et al., 2024). To mitigate these disparities and advance diagnostic equity, Canales emphasized the importance of being intentional about language equity when developing programs and ensuring effective patient-clinician communication throughout the diagnostic process.

LEVERAGING TECHNOLOGICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC INNOVATIONS

Amy Sheon, founder and president of Public Health Innovators, LLC, discussed strategies to improve digital literacy and internet access to advance diagnostic equity. Recent legislation was implemented to improve digital equity and access through the Digital Equity Act of 202110 and the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program.11 Sheon said that even if smartphones have become ubiquitous and are used by many people, disparities still exist for people over age 65, people with lower incomes, and people without a college education. Many recent adopters of this technology may have lower digital skills due to limited usage time, noted Sheon. Further, many households that are dependent on a single smartphone for internet access face barriers, including not having access when needed and difficulty uploading medical documents. When describing the lack of affordable broadband internet, Sheon said, “There is a history of digital redlining that mimics historic economic redlining.” Sometimes remote monitoring applications may not work on all devices or are not marketed to all of the diverse populations living with conditions like diabetes. To improve digital access and literacy, Sheon suggested adopting user-friendly technology, which can include “toolkits for inclusive development and deployment of digital medicine technology”; encouraging clinician facilitation of technology, which can include promotion of patient portals depending on accessibility; and monitoring equity in technology use to identify and characterize non-users. Sheon also emphasized the importance of “increasing the recognition of digital inclusion as an SDOH” and screening patients for digital readiness, as many curricula falsely assume patients have a device, connectivity, and basic digital literacy skills. Employing digital navigators to teach these skills could help bridge the digital divide and promote equity, she explained.

Akshar Abbott, ophthalmologist with the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), described the use of ocular telehealth to promote diagnostic equity in rural communities, noting that “rurality is a context, not a problem.” Abbott highlighted the difficulty with accessing subspecialty eye care in many rural communities, which puts people at risk of diseases which may cause blindness. He said people might have to drive more than 120 miles to see a neuro-ophthalmologist, and only 4 percent of zip codes have retina specialists, most of which are concentrated on the East or West coasts of the United States. Abbott said monitoring and managing illness through in-person outpatient visits limits access for patients, and shifting to home monitoring for measures like eye pressure can help remove the burden from patients. He also suggested improving clinical availability with increased hours and weekend appointments, expanding mobile health to bring care to people where they are,

__________________

10 For more information on the Digital Equity Act of 2021, see https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1841 (accessed October 23, 2024).

11 For more information about the BEAD Program, see https://www.ntia.gov/funding-programs/internet-all/broadband-equity-access-and-deployment-bead-program (accessed October 23, 2024).

and deploying clinicians into hard-to-reach or understaffed areas. Telehealth is a well-established strategy that enables e-consultations with specialists and offering asynchronous telehealth (i.e., patients can send messages, images, and test results to their clinicians for review later) and synchronous telehealth can sustain communication between patients and their clinicians. Abbott also discussed the potential to promote diagnostic equity through interprofessional collaboration via telehealth by providing an example of virtual medical retina clinics in VHA, which allow fundus photography to be sent to specialists to evaluate remotely, with optometrists and ophthalmologists working together to reach a diagnosis. This reinforces the idea that collaborative efforts among clinicians, especially in rural areas, can support timely and patient-centered diagnosis.

Devin Mann, professor at New York University Langone Health, described leveraging remote patient monitoring (RPM) to improve access to care and reduce diagnostic disparities. He noted that there is about a 20-year lag in technology diffusion, and access in underserved populations is often delayed. Mann explained how RPM uses digital technologies (i.e., wi-fi, Bluetooth, cellular technology) to assess and track patient health in real-time, outside of the typical clinical settings, and securely convey that information to clinicians, allowing for timely diagnoses and interventions and reducing the need for frequent in-person visits. At NYU Langone’s Healthcare Innovation Bridging Research, Informatics, and Design (HiBRID) Lab, Mann explained that the RPM platform captures patient data such as glucose, weight, peak expiratory flow, temperature, and pulse oximetry. For instance, patients can sync their home blood pressure devices and submit their readings so clinicians can suggest necessary changes to patients’ care plans. Challenges in implementation of operational RPM included limited digital literacy among patients, implicit bias in patient selection, and low reimbursement for RPM by some health insurers (Lawrence et al., 2023). Mann provided suggestions for developing and scaling RPM capacity: engaging a broad range of interested parties throughout implementation; building an end-to-end workflow; and conducting usability testing, including feedback from patients and communities. Mann also expressed enthusiasm for the potential role of artificial intelligence in bridging this equity gap, though there are benefits and challenges.

PATIENT- AND COMMUNITY-CENTERED APPROACHES

Anita Chopra, clinical assistant professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine, said barriers to accessing health care and resources are manifold and changing; community-based care is more than transplanting conventional medical care into communities; and training the health care workforce as health advocates is important in community settings. The most prominent barriers to access that lead to poor health outcomes are lack of health insurance, poor access to transportation, limited financial resources, and limited knowledge and education in health care, noted Chopra. She emphasized the importance of building trust by consistently listening to communities, engaging with them, and working with representative groups to mitigate disparities. Chopra and her colleagues started Northwest Health and Wellness Fairs to provide comprehensive preventative and primary care (e.g., mobile mammograms, dental vans, and blood donation) through community partnerships. This provides care to patients where they are and in a socially safe environment with cultural and language concordance. Connecting multiple health sectors directly with communities has been shown to benefit health behaviors, health outcomes, and social care delivery (Anderson et al., 2015). She emphasized that community-based care is most effective when the community is empowered to become an active partner in health care, in which the efforts and services provided by the program are steered by the community. Chopra concluded by discussing the importance of including medical students and residents in these outreach efforts, which teaches them clinical skills, communication skills, cultural insights, how to receive feedback in the diagnostic process, and is critical for their moral development. Moreover, “strengthening community partnerships helps build trust and engagement, addresses social determinants of health, develops collaborative efforts, provides innovative solutions tailored to the communities, and aims to create equitable health care systems,” said Chopra.

Traber Giardina, assistant professor at Baylor College of Medicine, discussed three patient-centered methods to

increase patient engagement in diagnostic safety. The first method of patient-centered journey mapping (i.e., visualizing a patient’s experience of a diagnosis) can help clinicians identify gaps where things went wrong as well as where things went right. Patient journey mapping promotes health equity by considering the varied experiences of patients and could encourage tailored solutions for different communities. The second method allows patients to review their own medical records. She said that one in five patients who have read the notes in their medical records have found a mistake, and they report those problems, potentially avoiding diagnostic errors. Patient access to electronic medical records fosters transparency and may improve understanding, said Giardina. She also described limitations to medical record access. Only 40 percent of patients and caregivers currently access their records (Johnson et al., 2021). Additionally, Giardina noted that patients often identify diagnostic concerns within the interpersonal interactions with clinicians such as their tone or body language, but patient narratives are often considered subjective while medical records are considered to be objective. In addition, she said, patients who found errors were less likely to trust their clinician as a result. A third method to strengthen diagnostic equity is engaging communities in the diagnostic process, being cognizant of community networks, and co-designing and collaborating programs. Giardina described organizing intensive workshops where community members can learn skills, share knowledge, and develop strategies for effective engagement; establishing mechanisms for continuous feedback from the community to refine initiatives; and utilizing online tools and social media to reach wider audiences and share information with community members.

Rachel Grob, director of the Qualitative and Health Experiences Research Lab at the University of Wisconsin Madison, discussed leveraging patient narratives to advance diagnostic equity. She opened with a video of a patient with breast cancer who explained how narrative studies honor complex identities and allow people to define themselves outside of pre-determined boxes: “To have the intersections that I do as somebody who is queer, nonbinary . . . I appreciate that narrative studies allow for some of the expansiveness to come through.” Grob’s work has focused on eliciting patient narratives of their diagnostic experiences and understanding how patients feel they are perceived by clinicians. In an ongoing study, Grob and her team sought information from patients about their interactions with the health system and how their self-described identities intersect with diagnostic experiences. Grob and her teams’ findings include themes of being ignored and not heard; being abandoned; not being believed or taken seriously; uncaring, hostile, or condescending communication; and negative assumptions. She gave an example of one patient who felt her health was reduced to aspects of her identity, e.g., being a woman, her education level, and weight. Patients also perceived that the quality of care they received was negatively impacted by being underinsured, lack of thorough investigation of their records, and being subjected to unnecessary tests. Grob concluded by discussing the importance of using these patient narratives to advance clinical education and improve the quality of the diagnostic process.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR CLINICIANS, RESEARCHERS, AND EDUCATORS

Marvella Elizabeth Ford, professor at the Medical University of South Carolina, described strategies to improve access and representation in clinical trials for tobacco-related lung cancer screening. In South Carolina, 27 percent of the state’s population is Black, 14 percent is rural, and the median income is $10,000 less than in the United States at large. In a study of patients with non-small cell lung cancers, Black people were 43 percent less likely than White people to have surgical resection at the same stage of diagnosis (Esnaola, et al., 2008), and underuse of this surgical intervention had resulted in higher mortality rates among the Black population. Ford said that while screening recommendations have been expanded recently by lowering the eligibility age to 50 years, disparities persist because younger patients not eligible for Medicare may not have insurance coverage for screenings. In an effort to overcome barriers to lung cancer surgery with a patient navigation intervention, Ford and her colleagues initially worked to recruit 200 Black participants among 5 sites but only identified 20 patients to enroll. With the help of the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program,12 Ford’s team

__________________

12 See https://ncorp.cancer.gov/ (accessed November 17, 2024).

expanded recruitment to 200 patients across 22 sites in the South, East Coast, and Midwest, which led to the Southeastern Consortium for Lung Cancer Health Equity, an initiative focused on increasing representation in cancer clinical trials.13 In this initiative, Ford’s team partners with federally qualified health centers to identify patients, provide screenings, and use patient navigators to help patients overcome barriers like transportation, inaccurate beliefs regarding cancer, and fear or mistrust that may lead to delays or refusal of care.

Denise Connor, professor at the University of California, San Francisco, said, “We can’t have clinical excellence without equity, and I think that is absolutely true when we think about [clinical] education.” She noted many health professional educators operate within a hierarchy of siloes, and said, “We give different amounts of resources and attention to them, and health equity and diversity, equity, inclusion, accessibility, and belonging (DEIAB) often are a small silo.” She emphasized integrating health equity and DEIAB throughout the diagnostic process. Connor described how situated cognition can be used to view diagnosis as contextual—i.e., it is a process that occurs in the context of the patient, the clinician, students, the technology, the environment, and social and historical contexts. Connor discussed updating the illness scripts clinicians often use, which traditionally consider a patients’ risk and predisposition, signs and symptoms, and possible pathologies, to consider how conditions and diseases may develop and present in populations that experience structural barriers, e.g., considering the problems that come with pathologizing behaviors that may in fact be adaptive responses to oppressive environments. She also teaches communication skills, educating students to communicate across differences and how to be part of equitable clinical teams. Connor noted that relationship-centered care, “helps us to individualize patients . . . and if we see a person as an individual as opposed to a member of stereotyped group, we are less likely to activate our implicit bias.” Echoing Chopra’s statements, Connor said clinicians have an obligation to be advocates for patients and communities and suggested working to identify and address disparities by disaggregating data, using patient navigators, and ensuring access to interpreter services.

Susana Morales, associate professor at Weill Cornell Medical College, discussed how to improve the pathway for diverse clinicians, health care workers, and researchers. She said her medical school experience was “the most racist experience of my life” and drove her to help others share their experiences and improve medical education practice. Almost one-half of the United States is non-White, she said, and African Americans and Latinos represent a little over 30 percent of the population. But only 10 percent of active physicians and only 7 percent of medical school faculty are from those groups, she said. “Some of the barriers and challenges include structural racism and lack of educational opportunity” as well as the financial barriers of expensive schooling, Morales noted. Faculty of color also have lower promotion rates and higher attrition rates, she said, and trainees feel a lack of support and mentorship. Morales and her colleagues formed the Diversity Center of Excellence of the Cornell Center for Health Equity. The program looks at the lifespan of a physician and focuses on education, research and community engagement, she explained, with programs for pre-med and medical students, residents, and fellows. They work to expand cultural competence and health equity training, provide mentoring through research programs and work in faculty development using a peer-near-peer program.

ENVISIONING THE FUTURE OF ADVANCING EQUITY IN DIAGNOSTIC EXCELLENCE

Urmimala Sarkar from the University of California, San Francisco, reflected on many of the cross-cutting themes of the first day of the workshop discussions. Sarkar started by stressing communication as a cornerstone of timely and accurate diagnosis and how intersectionality affects the diagnostic pathway. Importantly, Sarkar said education is needed for patients, clinicians, health care teams, and all people working within and adjacent to the health care system “to provide anti-racist care” and to develop “inclusive research and policy.” She emphasized a role for multi-level interventions that address multiple contributors to diagnostic disparities and interventions that work within the context of existing inequities.

__________________

13 For more information on the Southeastern Consortium for Lung Cancer Health Equity, see https://hollingscancercenter.musc.edu/news/archive/2022/03/15/hollings-southeastern-consortium-for-lung-cancer-health-equity-awarded-stand-up-to-cancer-grant (accessed October 24, 2024).

Technologies and algorithms can only help when there is clear communication among the different clinicians in the system and an effective workflow that incorporates medical specialties that might not directly communicate with the patient such as radiology, she said. She also highlighted the importance of embedding equity in the technology and algorithm development and implementation process. Sarkar concluded by saying that the onus is on health care systems, health care teams, and clinicians to partner with patients and communities to advance diagnostic equity.

In the final session, panelists highlighted key themes throughout the workshop for improving diagnostic equity. Colonel Steven L. Coffee of Patients for Patient Safety US underscored the value of treating patients as partners in their care and ensuring their voices are heard and respected. Aaron Carroll of AcademyHealth noted that disparities are not just a knowledge deficit problem, and if interventions focus too much on the clinical aspect, they ignore other factors that affect physician time and priorities for reimbursements, such as hospital administrators or insurance companies. Behavioral change, Carroll noted, is challenging, but systemic changes in reimbursements and quality measures could help produce that change as well as funding for long-term scalable solutions. Larissa Avilés-Santa of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities brought attention to the importance of a holistic approach that considers social and systemic adversities in addition to biological and pathological factors that impact health outcomes. Integrating specialty and primary care, she said, could help with communication between clinicians so diagnoses do not get missed. Reflecting on the presentations, Meghan Lane-Fall from the University of Pennsylvania agreed that trust is important but noted, “when we talk about trust it’s often communities’ trust in the health care system, clinicians, and health care providers. I would argue that trust needs to be bidirectional and that we, as clinicians, researchers, health care systems, actually need to trust patients.” Helen Burstin of the Council of Medical Specialty Societies emphasized, “equity has to be built in from the get-go into all of our diagnostic research and improvement.”

To incentivize action toward diagnostic equity, Burstin noted that hospital administrators might be incentivized when they consider how much diagnostic delays cause harm and increase costs, suggesting that using time to diagnosis or readmission as a metric would create a practical incentive. Lane-Fall noted that though policy could be useful, it is critical that people who are affected by policies are part of the decision making, and Coffee agreed that engagement from patient groups is critical. Coffee also said that hospital and health care leadership may be incentivized if they understand the value of including patients and diagnostic equity. “We have to show there is a business case and there is money to be made when we are being safer,” he said.

Suggestions from workshop participants for advancing equity in diagnostic excellence are outlined in Box 1.

BOX 1

SUGGESTIONS FROM INDIVIDUAL WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS TO ADVANCE EQUITY IN DIAGNOSTIC EXCELLENCE TO REDUCE HEALTH DISPARITIES

Improving Clinician Training, Care Delivery, and Clinical Operations

- Advance clinician and health care team education and training in cultural humility, anti-bias and anti-racist care, and holistic care to improve the provision of timely and accurate diagnostic care (Connor, Khan, Morales, Sarkar).

- Expand interprofessional collaboration among clinicians, especially in rural areas, to support timely and patient-centered diagnosis (Abbott).

- Integrate specialty and primary care to improve diagnostic outcomes and communication between clinicians (Abbott, Avilés-Santa).

- Tailor diagnostic interventions to match the unique needs, preferences, and values of patients (Chopra, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Henley).

- Employ systematic assessment of social determinants of health (SDOH) and develop interventions to address SDOH to improve diagnostic equity (Gillispie-Bell, Khan).

Emphasizing Patient- and Community-Centered Care

- Listen to patients and elicit patient narratives to understand how their interactions with the health care system and their complex identities intersect with diagnostic experiences (Connor, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Grob, Wyatt).

- Expand holistic patient-centered care that considers social and systemic factors (Avilés-Santa, Khan).

- Strengthen community partnerships to build trust and engagement, increase access to health care services (including screening), and increase representation in clinical trials (Chacón, Chopra, Ford, Giardina).

- Increase patient engagement in diagnostic safety through patient journey mapping, access to electronic medical records, and co-designing and collaborating with community networks (Giardina).

Focusing on Access and Health Equity

- Examine the scientific validity of using race in health care algorithms and its potential impact on exacerbating inequities (Gillispie-Bell, Sarkar).

- Improve language access by using interpreters and other methods to ensure effective communication and patient comprehension of instructions (Canales, Chopra).

- Use patient navigators to help patients better understand the diagnostic process, overcome barriers, build trust, and improve communication with clinicians (Connor, Farr, Ford).

- Integrate caregivers into the health care team and provide education to help patients better understand their diagnoses (Montoya).

- Integrate health equity from the inception to implementation of diagnostic interventions (Burstin, Sheon).

- Mentor and support diverse trainees, clinicians, and researchers to better reflect communities served by health care systems (Coffee, Connor, Grob).

- Improve availability of care with increased clinic hours and weekend appointments, expand mobile health, and deploy clinicians to hard-to-reach or understaffed areas to increase access to care (Abbott, Chacón, Sheon).

- Acknowledge the historical and intergenerational traumas that continue to contribute to health inequities in American Indian and Alaska Native communities (Deen).

- Consider how adverse childhood experiences can exacerbate diagnostic disparities and prevalence of chronic disease in different populations, especially in historically underserved communities (Deen, Duarte, Khan).

- Increase recognition of digital inclusion as an SDOH (Sheon).

Improving Technology Innovations

- Adopt user-friendly technology, encourage clinician facilitation of technology, monitor equity in technology use, screen patients for digital readiness, and employ digital navigators to improve digital access and literacy (Sheon).

- Expand use of remote patient monitoring to allow for timely diagnoses and interventions and reduce the need for frequent in-person visits (Abbott, Mann, Sheon).

Policy Opportunities

- Incentivize health care systems to improve equity in diagnostic excellence to reduce health disparities (Burstin, Carroll, Coffee, Lane-Fall).

- Engage patients in policy development to improve health equity in diagnostic safety (Coffee, Lane-Fall, Sarkar).

- Increase funding in research and long-term scalable interventions to address diagnostic inequities (Carroll, Crouch).

- Pursue and support multilevel approaches to diagnostic equity by addressing disparities in communities, increasing access to preventive health care and earlier interventions, and improving public health awareness and education (Khan, Sarkar).

Improving Data Collection for Research

- Improve rural data by increasing the sample sizes for data sets, removing public use restrictions, and developing a consistent definition of “rural” (Crouch).

- Enhance high-quality data collection and disaggregate data on historically underserved communities (Chacón, Connor, Crouch, Farr).

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. M., K. L. Adeney, C. Shinn, S. Safranek, J. Buckner-Brown, and L. K. Krause. 2015. Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015(6):Cd009905.

Canales, C., C. M. Ramirez, S. C. Yang, S. A. Feinberg, T. R. Grogan, R. A. Whittington, C. Sarkisian, and M. Cannesson. 2024. A prospective observational cohort study of language preference and preoperative cognitive screening in older adults: Do language disparities exist in cognitive screening and does the association between test results and postoperative delirium differ based on language preference? Anesthesia & Analgesia 139(5):903–911.

Caplan, L. S., D. S. May, and L. C. Richardson. 2000. Time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: Results from the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program, 1991–1995. American Journal of Public Health 90(1):130–134.

Doubeni, C. A., N. B. Gabler, C. M. Wheeler, A. M. McCarthy, P. E. Castle, E. A. Halm, M. D. Schnall, C. S. Skinner, A. N. A. Tosteson, D. L. Weaver, A. Vachani, S. J. Mehta, K. A. Rendle, S. A. Fedewa, D. A. Corley, and K. Armstrong. 2018. Timely follow-up of positive cancer screening results: A systematic review and recommendations from the PROSPR Consortium. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 68(3):199–216.

Esnaola, N. F., M. Gebregziabher, K. Knott, C. Finney, G. A. Silvestri, C. E. Reed, and M. E. Ford. 2008. Underuse of surgical resection for localized, non-small cell lung cancer among whites and African Americans in South Carolina. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 86(1):220–226; discussion 227.

Farr, D. E., T. Benefield, M. H. Lee, E. Torres, and L. M. Henderson. 2024. Multilevel contributors to racial and ethnic inequities in the resolution of abnormal mammography results. Cancer Causes & Control 35(7):995–1009.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., H. J. Kim, C. Shui, and A. E. B. Bryan. 2017. Chronic health conditions and key health indicators among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older U.S. adults, 2013–2014. American Journal of Public Health 107(8):1332–1338.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., S. Jen, A. E. Bryan, and J. Goldsen. 2018. Cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias in the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) older adults and their caregivers: Needs and competencies. Journal of Applied Gerontology 37(5):545–569.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., H.-J. Kim, C. A. Emlet, A. Muraco, E. A. Erosheva, C. P. Hoy-Ellis, J. Goldsen, and H. Petry. 2011. The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Seattle, WA: Institute for Multigenerational Health.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K., L. Teri, H. J. Kim, D. La Fazia, G. McKenzie, R. Petros, H. H. Jung, B. R. Jones, C. Brown, and C. A. Emlet. 2023. Design and development of the first randomized controlled trial of an intervention (IDEA) for sexual and gender minority older adults living with dementia and care partners. Contemporary Clinical Trials 128:107143.

Hoffman, K. M., S. Trawalter, J. R. Axt, and M. N. Oliver. 2016. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 113(16):4296–4301.

Hung, P., S. Deng, W. E. Zahnd, S. A. Adams, B. Olatosi, E. L. Crouch, and J. M. Eberth. 2020. Geographic disparities in residential proximity to colorectal and cervical cancer care providers. Cancer 126(5):1068–1076.

IHS (Indian Health Service). 2019. Disparities. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/ (accessed November 18, 2024).

Johnson, C., C. Richwine, and V. Patel. 2021. Individuals’ access and use of patient portals and smartphone health apps, 2020. ONC data brief, no.57. Washington, DC: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

Larson, E. H., C. H. Andrilla, and L. A. Garberson. 2020. Supply and distribution of the primary care workforce in rural America: 2019. Policy brief #167: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington.

Lawrence, K., N. Singh, Z. Jonassen, L. L. Groom, V. Alfaro Arias, S. Mandal, A. Schoenthaler, D. Mann, O. Nov, and G. Dove. 2023. Operational implementation of remote patient monitoring within a large ambulatory health system: Multimethod qualitative case study. JMIR Human Factors 10:e45166.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2015. Improving diagnosis in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21794.

Newman-Toker, D. E., N. Nassery, A. C. Schaffer, C. W. Yu-Moe, G. D. Clemens, Z. Wang, Y. Zhu, A. S. Saber Tehrani, M. Fanai, A. Hassoon, and D. Siegal. 2024. Burden of serious harms from diagnostic error in the USA. BMJ Quality & Safety 33(2):109–120.

Olfson, M., M. M. Wall, S. Wang, and C. Blanco, C. 2023. Prevalence and correlates of mental disorders in

children aged 9 and 10 years: Results from the ABCD study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 62(8):908–919.

Rodgers, C. R. R., M. W. Flores, O. Bassey, J. M. Augenblick, and B. L. Cook. 2022. Racial/ethnic disparity trends in children’s mental health care access and expenditures from 2010–2017: Disparities remain despite sweeping policy reform. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Safety 61(7):915–925.

Schulman, K. A., J. A. Berlin, W. Harless, J. F. Kerner, S. Sistrunk, B. J. Gersh, R. Dubé, C. K. Taleghani, J. E. Burke, S. Williams, J. M. Eisenberg, W. Ayers, and J. J. Escarce. 1999. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. New England Journal of Medicine 340(8):618–626.

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief has been prepared by Jennifer Lalitha Flaubert, Adrienne Formentos, and Bethany Brookshire as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteurs or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

*The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief rests with the institution. Kathryn McDonald (Chair), Johns Hopkins University; Yvette Calderon, Icahn School of Medicine; Steven Cohen, University of Rhode Island; Linda Geng, Stanford University School of Medicine; Cristina Gonzalez, New York University Grossman School of Medicine; Lakshmi Krishnan, Georgetown University; Spero M. Manson, University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Center; Kristen Miller, MedStar Health; Yamilé Molina, University of Illinois at Chicago; Ronald Wyatt, Achieving Healthcare Equity LLC; Clyde W. Yancy, Northwest University Feinberg School of Medicine.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Candace Henley, The Blue Hat Foundation; Urmimala Sarkar, University of California, San Francisco; and Amy Sheon, Public Health Innovators, LLC. Leslie J. Sim, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS This project was funded under contract number 75Q80124P00003 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors are solely responsible for this document’s contents, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this product as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

STAFF: Jennifer Lalitha Flaubert, Adrienne Formentos, Grace Reading (until October 2024), and Sharyl Nass, Board on Health Care Services, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/43298_09-2024_advancing-equity-in-diagnostic-excellence-to-reduce-health-disparities-a-workshop.

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. Advancing equity in diagnostic excellence to reduce health disparities: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/28573.

|

Health and Medicine Division Copyright 2025 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|