Roundtable on Obesity Solutions 10th Anniversary: Looking Back, Moving Forward: Proceedings of a Symposium (2025)

Chapter: 2 The First 10 Years

2

The First 10 Years

The next two sessions examined the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions’ founding in 2014 and the decade of collaborative work between the leaders and members of the roundtable to establish priorities, explore diverse topics, and form partnerships and collaborations.

REFLECTIONS FROM THE FIRST LEADERSHIP TEAM

Pronk moderated a discussion among the roundtable’s first leadership team. Pronk began by asking panelists why they were interested in serving on the leadership team when the roundtable first began. William P. Purcell, Vanderbilt University and Frost Brown Todd LLP, responded that his decision was based in part on the staff leader at the Institute of Medicine (IOM), Lynn Parker, who is an “irresistible force.” Parker had previously gotten Purcell involved in the studies Bridging the Evidence Gap in Obesity Prevention (IOM, 2010) and Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention (IOM, 2012); he said these experiences had convinced him of two things. First, obesity was among the most important challenges of our time. Second, “there was no better place on the planet” for people to come together to try to address challenges than the Institute of Medicine. Taken together, these factors made it “an easy ‘yes,’” said Purcell.

Mary Story, Duke University, said the years around the roundtable’s founding were the “golden years.” People working in the obesity field were filled with excitement, passion, commitment, and optimism, and there were some great successes. The 2010 Child Nutrition Act had taken steps to get junk food and sugary drinks out of schools, mayors had organized

community efforts, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) had committed $500 million to childhood obesity. At a time like that, “It was really easy to say ‘yes’ to being vice chair of the roundtable.” There was nothing like the roundtable happening at the time; it brought together people from different sectors, it focused on obesity throughout the life course, and it addressed multiple issues together, including nutrition, physical activity, sleep, and sedentary behavior.

Russell R. Pate, University of South Carolina, said he wanted to be involved in the roundtable primarily because he held the National Academies in high regard generally. Specific to the roundtable, he felt it was an opportunity to advance the position of physical activity in the Academies. There had been some projects at the National Academies that included a component of physical activity, said Pate, but there was room for growth. Second, he said, the roundtable was an opportunity to support a focus on primary prevention of overweight and obesity, and to advance the position of physical activity in public health. Pate said he has long thought that low levels of physical activity are a primary influence on the development of overweight and obesity; if the roundtable focused on primary prevention, physical activity would likely have a major focus.

Early Priorities and Highlights

The roundtable’s full name is the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions, observed Pronk, emphasizing the word solutions. Given this focus, he asked panelists to look back to their first 6 years on the roundtable and identify areas where a priority was set and met. Pate said he was grateful to see the roundtable did indeed advance the role of physical activity, both in the domain of obesity and in public health more generally. In contrast to some other groups, the roundtable has consistently worked to have a balanced approach to studying and addressing obesity, he said. Purcell said there were several priorities the roundtable has had from the beginning. First, a commitment to having everyone in the room; while science is necessary to address obesity, it must be paired with diverse perspectives from different areas. Second, the roundtable strove to focus on equity in all of its work. Purcell said that over the years of the roundtable and its many activities, the issue of equity was “never off the agenda.” Finally, the roundtable had a global focus. Obesity is not a challenge that the United States faces alone, and the solutions also need not come only from the United States, he said.

Story said that the roundtable was “ahead of its time.” From the beginning, issues such as weight bias and stigma, health disparities and equity, social determinants of health, and digital health technology were discussed. In addition, the roundtable’s incorporation of the lived experience of those with obesity was “cutting edge,” said Story. The roundtable

hosted speakers with lived experience, and these talks deeply affected members. One speaker—Patty Nece—even became a member of the roundtable. Story said the roundtable spent endless time creating and revising its mission statement and vision and was guided from the beginning by two principles: first, a commitment to accelerating progress toward equity, and second, using a policy, systems, and environmental lens. The roundtable created innovation collaboratives that provided a chance for people to delve into one topic; these efforts had an important impact, said Story.

Pronk noted that the roundtable remains a unique entity; it is the only group that regularly brings together multiple sectors with a specific focus on obesity. He asked panelists how the roundtable has influenced the field. Story responded that one area of impact has been the publishing of papers in the National Academy of Medicine’s NAM Perspectives. These papers, usually commentaries or discussion papers written by experts, are widely disseminated. The roundtable has published these papers each year; she highlighted three that were most influential: a 2017 paper by Kumanyika on equity in obesity prevention (Kumanyika, 2017); a landmark model framework by Bill Dietz that integrates community and clinical systems for prevention and management of obesity (Dietz et al., 2017), and a paper by Ted Kyle on stigma and obesity (Puhl and Kyle, 2014).

Pate said that in his opinion, the impact of the roundtable has been a mixed bag. The internal work of the roundtable has put a substantial focus on primary prevention, he said, but this focus has not necessarily translated into practice. While the roundtable puts out messages on prevention through its products, society as a whole remains much more focused on treatment than prevention. The recent rise of obesity drugs, said Pate, throws a curve-ball into this effort to focus on prevention. “Focusing on primary prevention in a society that … seems to be more drawn to treatment than prevention … is going to be a real challenge for the next decade,” he said.

Purcell said a major impact of the roundtable has been its view of obesity as a multifactorial issue. At the beginning of the century, he said, many people were looking for single causes and single solutions; for example, obesity was caused by pizza, or bagels, or smoking cessation. The APOP study convinced people that there was no “one solution,” and the roundtable never lost sight of this view. “Year after year … the roundtable has kept everyone in the field … focused on the multifactorial nature of obesity,” said Purcell.

Pronk shifted the discussion toward the future, asking the panelists to identify compelling issues that the roundtable should tackle moving forward. The focus on informing policy is critical, Story said, and some of the past successes in obesity have been accomplished through local, state, and federal policies. Another issue that warrants attention in the future is the commercial determinants of health, such as the marketing of unhealthy

foods to children. This is always the “elephant in the room,” said Story, and needs to be addressed by the roundtable.

Pate said that making progress on obesity will require a culture change. The work of the roundtable will get easier when “the operational definition of a high quality of life includes high levels of physical activity and healthy eating.” When this cultural shift occurs and these behaviors become normal and important to quality of life, he predicted, there will be real progress on overweight and obesity. Purcell shared that he thinks it is time for another consensus study on obesity. A study is needed to preserve the findings of what happened prior to 2014, and to examine what has been accomplished since. By looking at where the field has been and where it is now, said Purcell, a study can bring together the community for the decade ahead. His “strongest recommendation” for the roundtable is to find a way to make a consensus study happen, he said.

To close the discussion, Pronk asked each panelist to sum up their experiences on the roundtable in one word. Pate said “fabulous,” Story said “impact,” and Purcell said “optimism.”

FINDING FOCUS AND ESTABLISHING PRIORITIES

As the first leadership team of the roundtable passed the torch, the new leaders worked to find the focus for the group and to establish priorities for the future. Vice chair of the roundtable Christina D. Economos, Tufts University Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, spoke to symposium participants about how she and the other roundtable leaders developed a strategy to make the best use of the next 5 years. By 2019, she said, the roundtable had identified several needs.

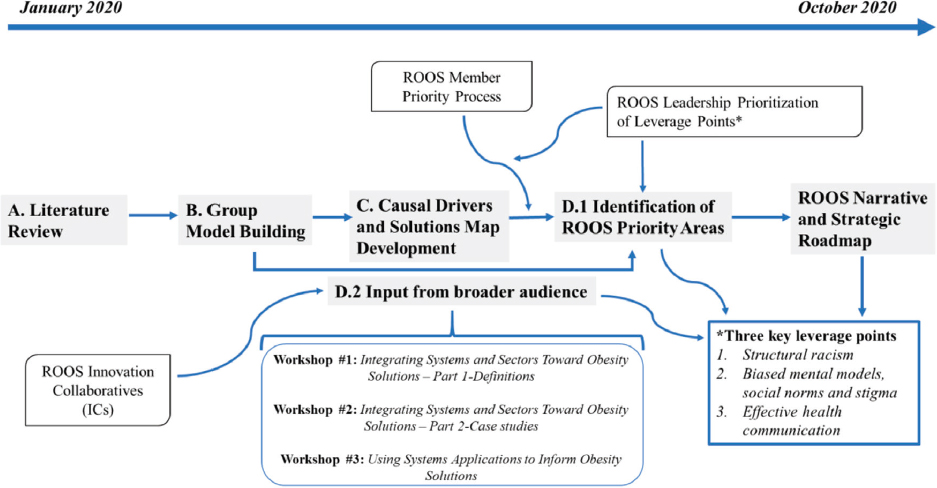

First, there was a need to adopt a multisector systems perspective and apply that perspective to advance, scale, and spread effective solutions. Second, there was a need to drive a paradigm shift in the way that people talked about obesity risk and prevention strategies. Third, there was a need for a multiyear strategic plan to address obesity. With these needs in mind, the leadership group used systems science methods to build a plan (Figure 2-1). Economos explained using a systems science method was important because of the complexity of the problem and the need to make sense of the complexity. The group started with a literature review, and then conducted an interactive exercise called group model building. This involved inviting the entire membership to “roll up their sleeves” and share their thoughts. Based on this input, the leadership team identified priority areas and developed a narrative and strategic road map.

Building trust was a key component of this process, said Economos. A tenet of systems science is to create opportunities to hear from everyone and understand diverse perspectives, and the roundtable was specifically

NOTE: ROOS = Roundtable on Obesity Solutions.

SOURCES: Presented by Christina Economos, July 24, 2024; Pronk et al., 2023. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier, CC BY 4.0.

designed as a forum for diverse members from a variety of sectors. There were a range of activities developed in order to give members opportunities to share concerns and solidify trust and engagement. Economos noted that this process began in January 2020 and the intention was to hold multiple in-person meetings and activities. The COVID-19 pandemic changed the way the work had to be done, but the team was able to use digital tools and stay true to the goal of being interactive and building trust.

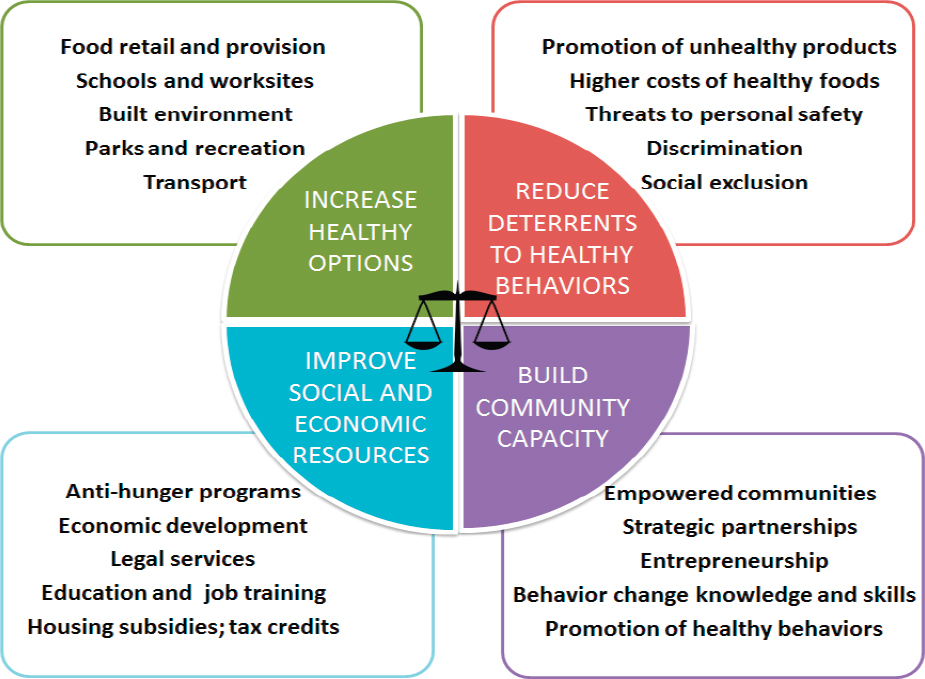

The literature review was conducted first, with roundtable members reviewing a list of evidence-based obesity solutions from authoritative organizations. The list was organized into six sector-specific or setting-specific groups, and members identified interventions that had “sufficient actionable evidence.” Economos noted that although these solutions had challenges—such as difficulties scaling, fragmentation, or inequitable outcomes—the evidence was promising. The work was centered around the Getting to Equity framework developed as part of roundtable activities in 2017 and published by Kumanyika in 2019 (Kumanyika, 2019) (Figure 2-2).

Economos explained that there were a number of reasons they chose to use this framework. The roundtable wanted to shift the conversation toward deeper determinants of obesity—not what an individual eats for lunch, but the food system that provides the food and influences the choice. As part of this, the roundtable pivoted from single solutions or single sector-based solutions into a view of the complex entirety and interacting variables; for example, the interactions between variables such as the

SOURCES: Presented by Christina Economos, July 24, 2024; Kumanyika, 2017. Reprinted with permission from the National Academy of Medicine.

built environment, discrimination, and economic development. Using the framework helped the group understand the need to identify and address structural drivers (or structural determinants) of obesity. She noted that while the roundtable was doing this work, the COVID-19 pandemic was exacerbating existing inequities, including in weight gain.

The next step of developing the strategic plan, said Economos, was using the identified interventions in a group model-building exercise. An expert facilitator and a core facilitation team were assembled to guide the group through the process. The team led the group through a number of activities, including an introduction to systems thinking, listing hopes and fears, and doing causal mapping in small groups. The products of this first phase were a list of preliminary drivers that populated a causal loop diagram, and a meeting summary and narrative that described the process, outcomes, and next steps.

The determinants and drivers of obesity were overlaid with aligned solutions in order to create an obesity systems map (Figure 2-3), said Economos. This map is complex, she said, but it emphasizes that there is no single solution to obesity and that “all of it is important.” Economos

NOTES: Yellow-highlighted areas indicate the roundtable’s priority obesity drivers. Blue-highlighted areas indicate the roundtable’s priority evidence-based solutions. Red dots indicate potential solutions. ACE = adverse childhood experience; CACFP = Child and Adult Care Food Program; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; EBT = electronic benefit transfer; ECE = early care and education; NSBP = National School Breakfast Program; NSLP = National School Lunch Program; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

SOURCES: Presented by Christina Economos, July 24, 2024; Pronk et al., 2023. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier, CC BY 4.0.

described the central part of the map, in which “obesity prevalence” is determined by what flows in and what flows out. Incidence of obesity—that is, the number of people developing overweight or obesity—flows into prevalence. People also flow out of prevalence, through either mortality or successful treatment. Prevalence is dynamic and always changing, she said, and can be affected by either changing what flows in or what flows out. In other words, if interventions can lower the incidence of obesity or improve the treatment of obesity, the prevalence of obesity will go down.

The group identified priority drivers that could affect either incidence or treatment, represented on the map in yellow. Proximal drivers include how an individual eats and moves; more distal drivers include economics, stigma, and racism. These distal drivers are things that cannot usually be changed

by an individual, said Economos, but society has the power to change them through policy. The evidence-based solutions identified from the literature (red circles) were aligned with both proximal and distal drivers to show where and how changes could be made. Putting all these pieces together on a map helped roundtable members see that while it is a complex issue, there are opportunities to do multisector, multi-intervention studies.

After developing the map, said Economos, the roundtable planned a number of public workshops to convey the importance of the systems thinking approach to a broader audience and encourage a paradigm shift in the field. The first workshop, Integrating Systems and Sectors Toward Obesity Solutions (NASEM, 2021a), provided background on systems theories, methodologies, and applications. Speakers explored how such determinants as inequity, power dynamics, relationships, and capacity affect systems can influence obesity, and how they can impact effective communications and cross-sector collaboration. The second workshop, Using Systems Applications to Inform Obesity Solutions (NASEM, 2021b), explored the applications of systems science to addressing obesity. It highlighted real-world case studies where people had already used systems thinking in their work and discussed why systems applications can be valuable for different sectors. These workshops were important, said Economos, for helping people understand the process that the roundtable was using and the way the members were thinking about the complexity of the issue.

The next step in the process was to identify priorities. The map had a huge variety of drivers and solutions, and it would have been “impossible” to try to address all of them. Economos said that the team used methods from the systems literature to identify priorities and tried to focus on deeper drivers that had not been adequately addressed in the field. The team conducted a number of exercises, including mapping the drivers onto the Meadows’ framework (Abson et al., 2017; Meadows, 1999); this meant deciding which drivers represented “shallow leverage points” and which were “deep leverage points” such as social structures and underpinning values.

Through this process, Economos said that the team identified three key leverage points: structural racism; biased mental models, social norms, and stigma; and effective health communication. These are present throughout the map and are connected to many of the proximal behaviors that take place every day. Some of the deep drivers have gotten worse over time, while others have not gotten the adequate policy attention they need. These priorities, along with the entire obesity systems map, helped to guide roundtable activities over the next 4 years, and served as a resource for researchers, organizations, and institutions involved with policy, prevention, and treatment of obesity. Economos said that she has noticed in recent years more discussion in the field about structural drivers of obesity, and she believes that the roundtable has played an important role in this shift.

A symposium participant asked Economos what big surprises came out of the strategic planning process. She responded that the biggest surprise was the enthusiasm of the group. It can be difficult for people from different disciplines and different sectors to communicate and work effectively together, but the individuals involved in the strategic planning process were excited to participate and felt ownership over the product in the end. Another surprise, she said, was the energy around and focus on the lived experience of people with obesity. The active participation of people with obesity—and their stories about stigma, social norms, and bias—led the group to hone in on these issues and prioritize them in their model.

Related to this, another symposium participant asked Economos what solutions the roundtable had identified to address the issues of biased mental models, social norms, and stigma. She said that when members discussed these issues at workshops, participants talked about the importance of training on clinical care and compassion, as well as the need for a cultural shift on how people think about obesity. A symposium participant agreed and said that the dominant mental model of obesity focuses on food and physical activity while ignoring factors like systemic racism and stress that can biologically trigger obesity. Economos said there is a respectable body of literature on the effect of stigma and discrimination on obesity, and she encouraged symposium participants to continue to explore these factors.

A symposium participant noted that people in society often think of problems as having a single cause and a single solution; he asked her how their complex, multisolution model of obesity has been received. Economos agreed that this is a challenge and said that it is particularly acute in the area of funding. There are very few sources of funding, she said, that are offering money to study the effect of multisector, multisolution approaches. One exception is the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ComPASS program, which is offering communities millions of dollars for up to 10 years of work on structural interventions that effectively use partnerships across multiple sectors. These complex approaches are expensive to study, she noted, but there are efforts being undertaken to determine which variables most effectively achieve the desired outcome. Economos said that she remains optimistic about the potential for multisector, multidisciplinary work on obesity, but that it requires breaking down silos and bringing people together.

This page intentionally left blank.