Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity (2023)

Chapter: 1 Statement of Task and Approach

1

Statement of Task and Approach

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, the opportunity to enjoy a healthy and prosperous life is often shaped by one’s race and/or ethnicity.1 As shown in this report, health outcomes and other measures of well-being are negatively affected by structural disadvantages, such as in education and income (see Box 1-1). Of course, no membership in a racial, ethnic, or tribal group predicts a given outcome, and each of the broad categories of race and ethnicity has considerable heterogeneity. However, the available data on health outcomes and other measures of well-being tell a story of structural disadvantage, preventable disparities in outcomes, and diminished opportunity. This report provides a framework for federal action that reviews contributing factors and identifies solutions—by building on past successes and addressing continued barriers—to structural racial, ethnic, and tribal health inequities.

THE URGENCY OF ADDRESSING HEALTH INEQUITIES

Although COVID-19 laid bare the reality of inequity in the United States, the disproportionate burden of poor health and inadequate access to health-protective social factors, such as economic stability, quality employment

___________________

1 The racial and ethnic categories discussed in this report should not be interpreted as being primarily biological or genetic. Race and ethnicity should be thought of in terms of social and cultural characteristics and ancestry and could be considered proxies that invoke racism (how race impacts how others perceive/treat different populations) and social characteristics (adapted from 62 FR 58782; see also the committee’s definition of key terms in the beginning of this report).

and education, and quality and affordable health care, faced by racial and ethnic populations that are minoritized, long preceded the pandemic (for a description the term “minoritized” and why it is used, see the Terminology section of this chapter). “The existence of racial and ethnic disparities in morbidity, mortality, and many indicators of health for African Americans, Native Americans, Hispanics, and Asians/Pacific Islanders was first acknowledged by the federal government in the 1985 Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. Since then, research has sought to identify additional disparities and explain the mechanisms by which these disparities occur” (NASEM, 2017). Extensive research on these health inequities demonstrates that these populations experience higher rates of illness and death for many different conditions, including heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, as well as lower life expectancies compared to non-Hispanic White people (CDC, 2021). Maternal health is another

important area—mortality is 2–3 times higher among Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) women (Petersen et al., 2019), and severe maternal morbidity (SMM) is higher among racial and ethnical people who are minoritized (Hill et al., 2022). An abundance of data points to social and structural determinants of health as the mechanism by which these disparities occur (NASEM, 2017, 2019e). Health inequity has consequences for the economy, national security, business viability, and public finances. For example, diminished health affects military readiness, and poor health impacts private businesses significantly (research from the Urban Institute shows that young adults who are less healthy and cannot find jobs in the mainstream economy are less productive and generate higher health care costs for businesses) (NASEM, 2017; Urban Institute, n.d.). Furthermore, health inequity has consequences for U.S. competitiveness in relation to other nations (see Box 1-2).

The Costs of Health Inequities

Public Health and Health Care

A plethora of evidence points to systemic and structural racism and discrimination as key elements of the mechanisms by which racial and ethnic health disparities occur (NASEM, 2017, 2019a, 2019c, 2019d, 2019e, 2022e). Therefore, a critical cost of racial inequity is poor health outcomes

for significant portions of the nation. The following section lays out examples of the stark reality of the state of health for such populations due to the lack of opportunities afforded to them. These patterns of inequity transcend most health outcomes. The COVID-19 pandemic brought this crisis into the nation’s consciousness as patterns of infection, hospitalization, and mortality took shape, mirroring the racial and ethnic health inequities seen everywhere else (CDC, 2022a; Hill and Artiga, 2022). In response to increasing understanding of the urgency of this crisis, many public health organizations, states, and other entities have declared racism a public health emergency, and the public health and health care sectors increasingly incorporate this understanding into how they approach their work (APHA, 2021).

These poorer health outcomes for groups that have been minoritized have important implications for health care spending. Research demonstrates that racial and ethnic inequities in health outcomes are responsible for significant avoidable expenditures (see below for estimates). Inequities in health care quality and access and other SDOH increase costs for health care consumers, providers, insurers, and taxpayers. Along with the increased burden of disease faced by racially and ethnically minoritized and tribal communities, inadequate or delayed care can lead to complications that require more extensive and expensive care, such as emergency department services or surgical interventions for heart disease (NASEM, 2017).

A 2009 analysis by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies found that 30.6 percent of direct medical care expenditures from 2003 to 2006 for African American, Asian, and Hispanic people were excess costs due to health inequalities and that eliminating inequalities in this same period for these populations would have saved $229.4 billion and more than $1 trillion in direct and indirect medical expenditures, respectively (LaVeist et al., 2009). That same year, the Urban Institute estimated that racial health inequity would cost health insurers $337 billion from 2009 to 2018 and that the annual costs would more than double by 2050 with increased representation of these populations among elderly people (Waidmann, 2009). Furthermore, a 2018 analysis by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation estimated that racial and ethnic health disparities amount to approximately $93 billion in excess medical care costs, $175 billion in economic impact of shortened life-spans (and 3.5 million lost life years associated with premature deaths), and $42 billion in lost productivity per year, as well as other costs, yielding $230 billion in projected economic gain per year if health disparities are eliminated by 2050 (Turner, 2018). A June 2022 analysis by Deloitte estimated that health inequities (in race, socioeconomic status, and sex/gender) account for $320 billion in annual health care spending and could eclipse $1 trillion by 2040 if left unaddressed (Dhar et al., 2022). The 2009 analysis by LaVeist et al. was updated in 2023; it found that in 2018, the estimated economic burdens of

racial and ethnic health inequities and education-related health inequities were $42–45 billion and $940–978 billion, respectively. The analysis showed that most of the “economic burden was attributable to the poor health of the Black population; however, the burden attributable to American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander populations was disproportionately greater than their share of the population” (LaVeist et al., 2023 p. 1).

Income Inequality

The economic and other costs individuals, families, and communities face due to racial and ethnic health inequities also perpetuate a cycle of accumulating disadvantage (see Chapter 3). High health care costs leave individuals and families struggling financially. Poor health and complications from chronic conditions impede the ability to work, jeopardizing access to employer-provided health coverage and the ability to provide for oneself and one’s family. Using an SDOH framework (see Figure 1-2) for public health illustrates the importance of economic stability, the ability to thrive financially, and access to quality employment and benefits to health and well-being (see Chapter 3 for a detailed discussion). These costs impact not only racially and ethnically minoritized populations but also the United States overall due to the implications for health care spending.

Societal Division, Political Costs

The existence of racial and ethnic inequity is antithetical to ideas written into the Constitution that all “are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” and to the prevailing conception of the United States as a country of equal opportunity for all.

Christopher described the nation’s inability to abandon the false belief in a hierarchy of human value as a point of vulnerability. In her book Rx Racial Healing: A Guide to Embracing our Humanity, she argues that “current levels of societal division” make it crucial to engage in the work of truth, racial healing, and transformation, for which her book provides a framework (Christopher, 2022) and which can help foster collective action to address health equity. Such societal and political divisions have led to the politicization of health, health care, and other areas (Pew Research Center, 2020). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission following apartheid in South Africa (United States Institute of Peace, 1995) and Canada’s more recent efforts to confront the traumatic history and legacy of its residential school system and its impact on Indigenous families and communities provide precedents for taking action (Crown-Indigenous Relations

and Northern Affairs Canada, 2022). The racial justice protests that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, and studies illustrating the depth of the U.S. political divide (Dimock and Wike, 2021; Kort-Butler, 2022) support Christopher’s argument. The UN’s World Social Report 2020 draws similar conclusions about the negative consequences and vulnerability of inequity, including social unrest, discontent, destabilized political systems, threats to democracy, and violent conflict (United Nations, 2020).

ROOT CAUSES OF HEALTH INEQUITIES IN THE UNITED STATES

“The factors that make up the root causes of health inequity are diverse, complex, evolving, and interdependent in nature” (NASEM, 2017). The inequitable distribution of disease and well-being in the United States shows that social factors, such as economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context, as well as the upstream structural factors that impact them, including governance systems and processes and the nation’s cultural and historical context, play a critical role in health outcomes (see Chapters 2–7 for detailed examples of these factors) (NASEM, 2017, 2023b; University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2023). These social, environmental, economic, and cultural determinants of health are “the terrain on which structural inequities produce health inequities” and the conditions in which people live.

For example, the effect of interpersonal, institutional, and systemic biases in policies and practices (structural inequities) is the “sorting” of people into resource-rich or resource-poor neighborhoods and K–12 schools (education itself being a key determinant of health) on the basis of race and socioeconomic status. Because the quality of neighborhoods and schools significantly shapes the life trajectory and the health of the adults and children, race- and class-differentiated access to clean, safe, resource-rich neighborhoods and schools is an important factor in producing health inequity. Such structural inequities give rise to large and preventable differences in health metrics. (NASEM, 2017, pp. 100–101)

Research demonstrates that the inequitable pattern of these social risk factors across race and ethnicity are in large part a consequence of structural disadvantages for minoritized communities that were, in no small measure, initiated by historical federal policies (NASEM, 2017). These decisions, some made centuries ago, have guided the organization and governance of society and the distribution of resources, affecting all generations since. The U.S. history of assimilation, removal, and extermination of

American Indian people, enslavement of African and African American people, colonialism, and immigration policy have been key to how the country is stratified, impacting outcomes across health, education, socioeconomic status, and other measures of well-being even today (see Chapter 2 for more information) (NASEM, 2017).

The outcomes are evident in the disproportionate burden of poor health faced by disadvantaged groups, such as low-income individuals and families, people living in historically segregated and disinvested areas, those without access to high-quality employment and educational opportunities, members of sovereign nations and tribes, and people who are American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Black, Latino/a, or Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander. Owing to the U.S. history and prevailing legacy of structural racism (see Key Terms for definition), patterns of inequity with regard to these social factors fall along racial and ethnic lines (see Chapter 2 for more details). There are higher rates of childhood asthma among low-income households, higher morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases among individuals with lower educational attainment, and higher exposure to air pollution among residents of disinvested communities—those in low-income, disinvested communities are disproportionately racially and ethnically minoritized. Moreover, the effects of the structural determinants of health on many health outcomes persists when accounting for income and education. For example, New York City data from 2008 to 2012 demonstrate that, among women who did not finish high school, SMM, a measure of life-threatening complications of pregnancy, labor, and delivery, was three times higher for Black than White women. SMM was 2.4 times higher among Black women with an undergraduate degree or higher compared to White women who did not finish high school (Angley et al., 2016). This report reviews the social and structural factors (e.g., policy) contributing to racial and ethnic health inequities and provides solutions for advancing racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity at the federal level.

The following four case examples illustrate some of the ways different populations are affected by health inequities via uneven access to the SDOH. These examples are not meant to be comprehensive; other racialized and ethnic groups and multiracial individuals experience similar inequities but unique outcomes, and these populations are highlighted in other parts of the report.

The Experience of Black Men

Health outcomes for Black men are an example of how structural racism—via the health care, criminal legal, education, and employment systems—is expressed as health vulnerabilities. Black men live an average of 74 years, 4.4 years less than the average for non-Hispanic White men,

and face high rates of mortality from preventable chronic illness (HHS, 2023). Compared to other populations, young Black men are less likely to have a regular source of primary care, have insurance coverage, and rate communication with a provider as positive, and they often see the health care system as complicit with other aggressive and oppressive systems, such as the law enforcement system (Vasquez Reyes, 2020). Overall, Black Americans die at higher rates than White Americans of heart disease, stroke, cancer, asthma, influenza, pneumonia, HIV/AIDS, and homicide (HHS, 2023). Such negative health outcomes are exacerbated or caused by social inequities. “Young Black men have poor access to quality primary care which is especially devastating when we consider that many of these young men are often [affected] by racially inflected violence in their communities through their interactions with social institutions and systems.”2 Young Black men face unique burdens as a result of racist stereotypes about anger, violence, and criminality that society has imposed on their identities. These social stigmas lead to outcomes that expose them to poor health outcomes. For instance, about 1 in 1,000 Black men and boys in America can expect to die at the hands of police (Edwards et al., 2019). Furthermore, 1 in 3 Black boys born today will be sentenced to prison during his lifetime, compared to 1 in 17 White boys—which is due not to higher crime rates by Black boys but rather to social and structural factors at play (NAACP, 2021; NASEM, 2022d). These social and structural factors limit Black men’s ability to live a healthy and prosperous life.

The Experience of American Indian and Alaska Native People

The lived experiences of AIAN people are also shaped by structural disadvantage and a history of extermination, removal, and assimilation in the interest of Euro-American expansion (Moss, 2019). For example, life expectancy in 2019 was 73.1—5.1 years lower than the White and 12.6 years lower than the Asian population (NIH, 2022). The AIAN population also saw a sharper decrease in life expectancy from 2019 to 2021 than any other racial or ethnic group (Goldman and Andrasfay, 2022). American Indians have rates of high infant mortality, maternal death, and diabetes, with the most resulting amputations and other complications (IHS, 2014). Despite these poor outcomes indicating an urgent need, access to and funding of treaty-mandated health care remain problematic. The Indian Health Service (IHS) receives less funding per person than Medicaid,

___________________

2 Quote by John A. Rich, Rush University Medical Center, at Meeting 3 of the committee (see https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/08-01-2022/review-of-federal-policies-that-contribute-to-racial-and-ethnic-health-inequities-meeting-3-part-2 [accessed May 30, 2023]).

Medicare, VA, or federal prisons. Indian Country often has health care workforce shortages and inadequate health care and infrastructure funding (Heisler and McClanahan, 2020). For example, accessing medical care later in the calendar year can be problematic, as the IHS referred care program begins to run out of resources because it does not receive advance appropriations (Heisler and McClanahan, 2020). American Indian populations also have high rates of mental health and substance use challenges, resulting in some of the highest U.S. suicide and homicide rates. Violence is an especially pertinent issue for AIAN women, for whom murder is the third leading cause of death in some counties, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Invisibility is another—of 5,712 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls reported in 2016, only 116 were logged in the U.S. Department of Justice federal missing persons database (Lucchei and Echo-Hawk, 2018). The erasure of American Indians in data collection cuts across the spectrum of measures for health and well-being; a common saying is “born Native but dying White.” Thus, as serious as the picture that the data paint, the reality is likely much worse. In addition, tribes are domestic dependent nations, “Wards of the State,” sovereigns, and at the “sufferance of Congress” for their status as federally recognized tribes due a federal trust responsibility stemming from the Marshall Trilogy from the early 1800s, which is the basis of Indian law today (NCAI, n.d.).

The Experience of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander People

The lived experience of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) people is also marked by long-standing historical trauma that has resulted in racial segregation, physical displacement, declining health, higher death rates, premature mortality, stereotyping, and inadequate data leading to a level of invisibility (Alexander, 1899; Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, 2005; Faucher, 2021; Galinsky et al., 2017; Kaholokula et al., 2020; Kana‘iaupuni and Malone, 2006; Klest et al., 2013; Morey et al., 2022; Ogden et al., 2017; Panapasa et al., 2010; Tobin, 1967; Xiang et al., 2020). In 1997, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) disaggregated the single Asian or Pacific Islander category into two independent categories and required federal programs to adopt the new standards by January 1, 2003. When data for NHPI are combined with Asian population data, this aggregation masks the true outcomes for NHPI people—who are composed of Indigenous, migrant, and immigrant groups—for all measures (Moon et al., 2022; Taparra and Pellegrin, 2022). This lack of data has damaging effects as inadequate basic national-level data limits knowledge on health outcomes, perpetuating invisibility and lack of representation, and depriving NHPI people of access to effective resources and interventions.

These factors underscore how structural inequities perpetuate disparities in population health outcomes. NHPI people continue to face a disproportionate burden of disability, morbidity, and mortality (Galinsky et al., 2017; Morey, 2014; Pillai et al., 2022). Compared to other populations, they are more likely to have elevated levels of asthma, heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes and least likely to have a healthy body weight (Galinsky et al., 2017). Overall, NHPI people have the highest end-stage kidney disease incidence rate among all races in the 50 states (921, 95 percent CI: 895–987, per million population per year)—2.7 times greater than White and 1.2 times greater than Black Americans. In the U.S. Pacific Island territories, the rate was 941 (95 percent CI: 895–987) (Xiang et al., 2020). Common factors that lead to health inequities in the Native Hawaiian population include poverty, low levels of high school completion, exposure to pollutants, poor physical environments, limited access to care, and discrimination (Liu and Alameda, 2011; Morey, 2014). Pacific Islander people in the Los Angeles County area report some of the highest levels of childhood and adult asthma, and their heavy concentration in the lawn care and construction industries also represents a high risk of ongoing exposure to pesticides and dangerous chemicals (LACDPH, 2022). In 2020, NHPI people in Los Angeles County were reported to have the highest mortality rate (1,324 per 100,000) and lowest life expectancy (73.5 years compared to 82.3 years for the county overall) (LACDPH, 2022).

Although these inequities are considerable, NHPI communities have the potential to thrive. As one of the most rapidly growing demographic groups in the country, they live in every state (Kehaulani Goo, 2015; OMH, 2023). NHPI people are increasingly attending college, often through athletic scholarships but also due to a growing recognition of education as a way forward for their children (Teranishi et al., n.d.; Tran et al., 2010). Community and faith-based organizations are assuming a greater role as stakeholders in community-based research activities and aggressively ensuring that relevant health, educational, housing, and economic information reaches the neighborhoods they serve (Burrage et al., 2023; Galinsky et al., 2019; McElfish et al., 2018; Panapasa et al., 2012).

The Experience of Latino/a Immigrants

The Latino/a population is the largest minoritized group in the United States, and 19.7 million people—34 percent of the total immigrant population—identify as Hispanic or Latino (Esterline and Batalova, 2022). Undocumented Latino/a people compared to documented have worse health outcomes for many measures (such as higher blood pressure, hypertension, depression, and anxiety), and undocumented Latina immigrants are more likely to have low-birthweight babies. Limited access to health care,

health-protective resources (such as social and economic factors), and interactions with immigration enforcement actions are mechanisms that contribute to inequities within the population (Cabral and Cuevas, 2020). Furthermore, social mobility is limited, as is access to health care, placing undocumented Latino/a people at an increased risk for disease. Lack of legal status is a barrier to higher educational attainment—half of the Hispanic undocumented population aged 18+ has less than a high school education (Cabral and Cuevas, 2020). These issues transfer generationally as well. For parents who do not have experience navigating the health care and social systems, cultural and language barriers coupled with transportation and economic challenges hamper their ability to access public programs, such as health care, for their children (Aragones et al., 2021; Flores et al., 1998; Oropesa et al., 2016).

Additional Populations and Data Limitations

These four examples are only a small snapshot of the experiences of minoritized racial and ethnic populations. Much more is discussed elsewhere in this report. For example, the Asian American population has roots in more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. There are groups within the Asian community who suffer greater health inequities than the group as a whole and have unique experiences, histories, cultures, languages, and needs. The Hmong people differ significantly from other Asian American populations in many social factors (such as income and education levels), which may put them at risk for poorer health (Lor, 2018). Black men were discussed, but Black women also face significant inequities—for example, maternal mortality is three times higher among Black than White mothers (CDC, 2022d; Hoyert, 2022), and their infant mortality rate is more than two times higher (CDC, 2022b). In addition, the Black population includes people with very different socioeconomic characteristics, such as individuals who immigrated from Sub-Saharan Africa versus those who represent multigenerational North American African Americans (see Chapter 2 for more information).

Although the statistics on racial and ethnic inequities in health outcomes—including those in the examples—are striking, they are complicated by problems such as data inaccuracy, sometimes intentionally missing data for certain populations, and failure to disaggregate data (see Chapter 2). In addition to these examples, failure to accurately record race for AIAN people in medical records erases them in the data (Espey et al., 2014; Jim et al., 2014). Some populations, such as people of Middle Eastern or North African descent, are entirely excluded from categories for race and ethnicity because they are counted as White under current federal standards even though they are routinely racialized as non-White. For NHPI populations,

aggregation of data under broad categories, such as “Asian,” “Asian and Pacific Islander,” or “Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander,” masks the complexity of the challenges faced by these different populations and reinforces racist and colonialist views of racial and ethnic minorities as monolithic. Another important consideration is that ethnicity is currently treated separately from race in most data collection efforts, but some consider this a flawed approach and advocate for using a mutually exclusive single race/ethnicity variable because not doing so can sometimes limit the ability to identify inequities and/or distort findings due to misclassification or missing data points. “For example, not providing a mutually exclusive race/ethnicity category for Latino individuals forces them to artificially choose a race” (Flores, 2020, p. 2). For the purpose of this report, the committee treats these as separate categories because that is how the majority of the data are collected.

The understanding that data on health outcomes for racially and ethnically minoritized populations are limited is a critical component of the committee’s approach to its task (see the Committee’s Approach section; see Chapter 2 for a detailed discussion on data limitations and opportunities). Given the limited and inaccurate data for specific populations, the committee relied on a variety of data to capture a fuller understanding of the mechanisms that result in health inequities for these different populations and made the intentional decision to center lived experiences and other forms of knowledge as data throughout this study.

Role of Communities

Although the illustrative examples provided here and elsewhere in the report are discouraging, racially and ethnically communities that are minoritized have flourished despite many barriers. For example, a 2017 National Academies report highlighted nine communities3 that advanced health equity by addressing various SDOH—that is just a small sample of communities’ work nationwide (NAM, n.d.; NASEM, 2017; RWJF, n.d.; TFAH, 2018). In addition, some communities have made significant gains on health outcomes. For example, although CDC reported in 2022 that over the last 2 years, the life expectancy of Black people declined to about 71 years old (6 years lower than their White counterparts), in certain communities, it is much higher—in Manassas Park, VA, and Weld County, CO, it is 96 years. Black people are living longer in some smaller jurisdictions as well (Brookings Metro and NAACP, n.d.).

___________________

3 These include Blueprint for Action in Minneapolis, MN; IndyCAN in Indianapolis, IN; Magnolia Community Initiative in Los Angeles, CA; Mandela Marketplace in Oakland, CA; and WE ACT for Environmental Justice in Harlem, NY (NASEM, 2017).

In the majority of these examples, community voice and expertise played a strong role in creating and implementing strategies designed to advance health equity. Ensuring the inclusion of community leaders and organizations in federal policies that contribute to health equity is a key theme in this report (see Guiding Principles). Communities are defined as population groups residing in a specific zip code, census tract, or county or sharing another commonality, such as race or ethnicity, gender, or age (NASEM, 2017).

Although community participation is often touted as a value in policy making and program design processes, two problems persist: a lack of specificity as to what constitutes community engagement or inclusion and of accountability mechanisms to ensure that authentic community input has been integrated into the policy or program. Figure 1-1 illustrates the International Association for Public Participation’s Spectrum of Public Participation (IAP2). This model is useful because it enables both specificity and accountability. To advance health equity, the role of communities—particularly those that suffer most from current health inequities—needs to move further to the right on this spectrum (CDC, 2011; NAM, 2022; NASEM, 2017; South et al., 2015; Wallerstein et al., 2020). Such an approach can help partners better understand and address the roots of health issues and protect against creating repressive partnerships (CDC, 2011; NAM, n.d.; Viswanathan et al., 2004).

SOURCE: IAP2, 2018; Credit: © International Association for Public Participation www.iap2.org.

Although including community voice in decisions that will affect them is crucial, “communities exist in a milieu of national-, state-, and local-level policies, forces, and programs that enable and support or interfere with and impede the ability of community residents and their partners to address the conditions that lead to health inequity. Therefore, the power of community actors is a necessary and essential, but not sufficient, ingredient in promoting health equity” (NASEM, 2017)—supportive policies at all levels are also needed.

THE COMMITTEE’S APPROACH

The committee was asked to (1) review federal policies (e.g., social, economic, environmental) that contribute to preventable and unfair differences in health status and outcomes experienced by all U.S. racially and ethnically minoritized populations and (2) provide conclusions and recommendations that identify the most effective or promising approaches to policy change with the goal of furthering racial and ethnic health equity (see Box 1-3). The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Minority Health (OMH) requested this study in response to a request in a Congressional Appropriations Report.4 The committee was not asked to review the state of U.S. health inequities but does provide background on this throughout the report. Although there

___________________

4 House conference report (H. Rept. 116-450—Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2021).

are many examples of federal policies that have advanced health equity, the committee was not asked to review such policies. However, because many successful policies can be changed to be even more effective or implemented more broadly, such policies are reviewed in this report (see Box 1-4).

A range of views exist on the role and place of government in U.S. society. However, the committee focused on the evidence of how federal policies—or lack thereof—have contributed to health inequity and looked to federal policy levers for solutions, as this was its charge, with a focus on policies and programs in the executive and legislative branches of the federal government. Policies at other levels of government may be more or less important for contributions and/or solutions, but the committee does not comment on or address these issues, as they are not part of the Statement of Task. The following section reviews the terminology and key terms used in this report and the committee’s approach to its Statement of Task.

Terminology

Over time, terminology related to racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity has significantly evolved (NASEM, 2021c). Lack of “person first” language, stigmatizing language, and omitting some populations from data collection have contributed to exclusion, lack of trust, and misinformation. Therefore, throughout this report, the committee strived to use language that is respectful, accurate, and maximally inclusive. It attempted to use language that reflects how individuals and groups wish to be addressed, but consensus does not always exist on preferred terms, and these preferences may evolve.

Rather than referring to “racial and ethnic minorities,” “members of minority groups,” or “underrepresented minorities,” this report uses the term “minoritized,” which makes the distinction that being minoritized is not about the number of people in the population but rather about power and equity and points to the intersectionality of being a minoritized member of a minoritized group (Wingrove-Haugland and McLeod, 2021). “Minoritized” demonstrates that dominant groups “minoritize members of subordinated groups rather than obscuring this agency” (Wingrove-Haugland

and McLeod, 2021). “Minoritization recognizes that systemic inequalities, oppression, and marginalization place individuals into ‘minority’ status rather than their own characteristics” (Sotto-Santiago, 2019). However, “minoritized” will not resonate with all. Some link this term to hierarchal thinking related to the dehumanization of specific populations. “While using minoritized risks creating a false equivalence that sees all instances of being minoritized as equal and discounting unique forms of oppression. . . . using this term carefully can ensure that its advantages outweigh these risks” (Wingrove-Haugland and McLeod, 2021).

This report uses “Black people” when referencing African American and other people who are part of the African diaspora, as the term is often understood to be broader and include persons whose cultural history is not grounded in the United States (NASEM, 2021c). Similarly, the committee has chosen “Latino/a” to refer to persons with cultural connections to Latin America, recognizing that some people may prefer “Hispanic,” “Latinx,” “Latine,” or another term. The phrase “American Indian and Alaska Native” is preferred because this is the population recognized under treaty rights. See the frontmatter for definitions of key terms in this report.

In this report, as with many other published reports, the comparison group when looking at health inequities is typically non-Hispanic White people. Electing a culturally dominant group as the reference group can subtly imply the notion that dominant groups are the most “normal.” However, this report does not do so because Whiteness should be the aspiration or it is centering Whiteness. Rather, this comparison is made because White people have not directly suffered the impacts of structural racism and other structural determinants of health due to race.

Societal understanding of gender identity is rapidly evolving. Gender-related terms are used, but when applicable, broader terms, such as “pregnant people” in place of “pregnant women,” to acknowledge the diversity of gender identities and point to ways that our common language can be updated to accord greater respect to all people. “LGBTQ+” refers to individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (NASEM, 2021c).

Sometimes the terms used in this report, however, are determined by the terms or definitions in data systems or a specific research study referred to or summarized. For example, if referencing data collected or analyzed for “Native Americans,” that terminology is used.

Definitions

Definitions are available in the “Key Terms” section; definitions provided are how the terms are used in this report, and National Academies, government, and other reports may define them differently. One important

distinction is that health disparities and health inequities are not the same. Health disparities are differences among specific population groups in the attainment of full health potential that can be measured by differences in incidence, prevalence, mortality, burden of disease, and other adverse health outcomes (NASEM, 2017). “Health inequities” implies that these differences are unfair and preventable (Meghani and Gallagher, 2008). Health equity is the state in which everyone has a fair opportunity to attain full health potential and well-being, and no one is disadvantaged from doing so because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance. Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities and historical and contemporary injustices and eliminate health and health care disparities due to past and present causes (CDC, 2022c; NASEM, 2017). By these definitions, addressing inequities requires transformational changes, including in how resources are allocated, decisions are made, and goals and objectives are established; “business as usual” perpetuates inequities. It is important to emphasize that equity is not interchangeable with equality—equality is the treatment of all individuals in the same manner. Equality assumes a level playing field for everyone without accounting for historical and current inequities.

Report Conceptual Framework

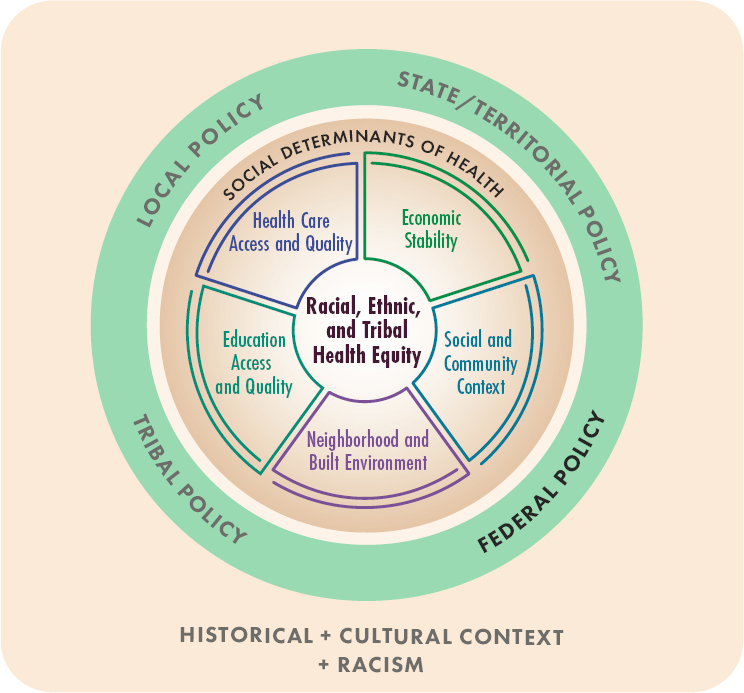

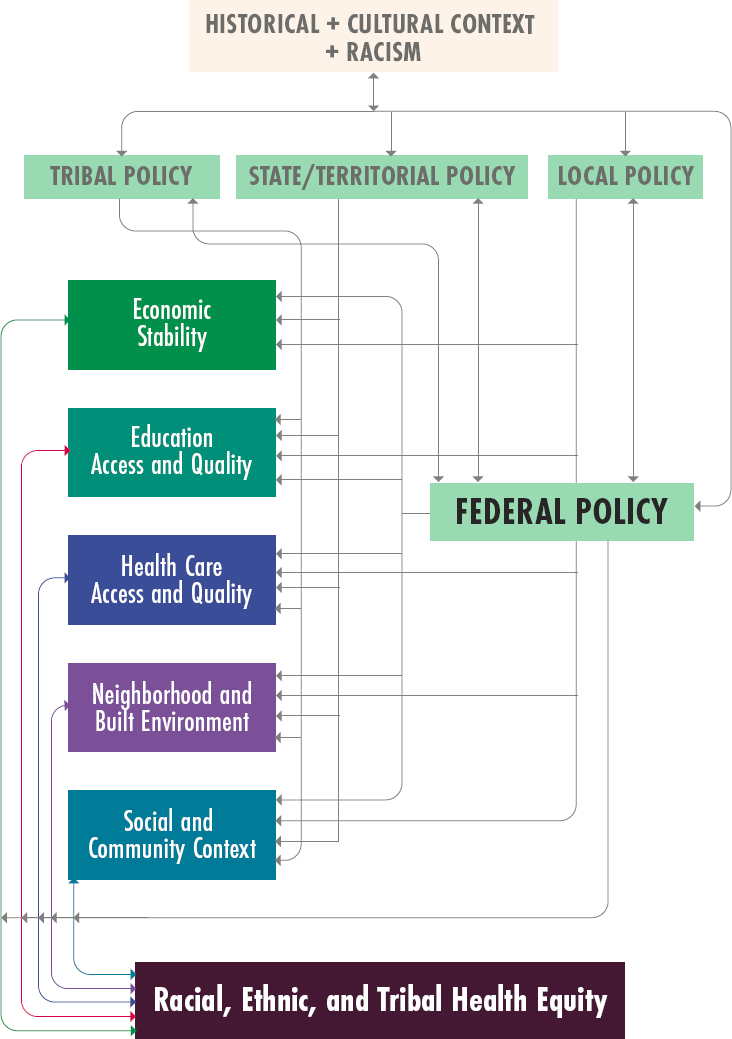

Given the broad task provided to the committee (see Box 1-3), it developed a conceptual framework (Figure 1-2) to approach its analysis and this report. The framework uses Healthy People 2030’s five categories for the SDOH (HHS, n.d.), recognizing the role that the inequitable distribution of SDOH, such as economic stability, health care access and quality, education access and quality, social and community context, and neighborhood and built environment, play in perpetuating racial and ethnic health inequities.

Moreover, the SDOH are shaped by structural determinants, including local, state, tribal, territorial, and federal policies and laws, and societal-level aspects of the historical and cultural context, such as structural racism. The latter refers to the totality of ways in which a society fosters racial and ethnic inequity and subjugation through mutually reinforcing systems, including housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, and the criminal legal system (Bailey et al., 2017). These structural factors “organize the distribution of power and resources (i.e., the social determinants of health) differentially” among racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, perpetuating health inequities (NASEM, 2019e). The key difference between institutional and structural racism is that structural racism happens across institutions; institutional racism happens within institutions (“systemic racism” is another term).

The intertwining relationships between the SDOH, laws and policies, government policy, and historical and cultural factors are more complex than can be clearly visualized in a single model. Historical and cultural factors at the larger societal level also impact laws and policies, which affect the SDOH and health inequities. Figure 1-3 illustrates the complexity of the relationships between the social and structural determinants introduced in Figure 1-2.

Although not represented in Figures 1-2 and 1-3, the committee also incorporated a life course lens in its analysis and throughout this report. Such approaches to examining health inequities incorporate both structural and developmental perspectives, considering how social and structural determinants of health, particularly exposures “during sensitive life stages” can “shift health trajectories” and “shape health within and across generations” (Jones et al., 2019).

Key Principles

The committee adopted a set of principles to guide its work (see Box 1-5), alongside the conceptual framework (which provides a higher-level view of its approach). These principles are essential when embarking on health equity work and were informed by a large and growing body of research on the SDOH (IOM, 2003a; Link and Phelan, 1995; McGinnis and Foege, 1993; NASEM, 2017) and input from experts, policy leaders, and other key stakeholders gathered via public comment and information-gathering sessions.

- Health is physical and mental well-being, but it also includes wellbeing in social, economic, and other factors, all of which are necessary for human flourishing.

The committee defined health as not only medical but also social supporting capacities for human flourishing (CDC, 2017). The implications of using this holistic approach are that federal policies can impact health both directly (e.g., access to medical care via Medicaid Expansion) or indirectly (e.g., reducing family economic insecurity via Earned Income Tax Credit [EITC]). In addition, all people should have the opportunity to attain health and well-being. “Rebuilding a healthy social contract for the U.S. requires focusing on health as a foundation for the ‘safety and happiness’ of the people. Those are the words used in the Declaration of Independence as a translation of the ancient Roman dictum salus populi suprema lex esto (‘let the health of the people be the supreme law’)” (Impact Initiative, n.d.). This pursuit needs to include all people, and this is rooted in the “concept of solidarity that is a deep but submerged strand in American history” (Impact Initiative, n.d.). This holistic view of health is needed for all people to flourish.

- Every federal policy has the potential to affect population health.

Given the role of federal policies in both impacting and securing health and well-being, a Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach is needed when assessing health equity. HiAP is informed by an SDOH framework and “. . . a collaborative approach that integrates and articulates health considerations into policy making across sectors to improve the health of all communities and people. HiAP recognizes that health is created by a multitude of factors beyond health care and, in many cases, beyond the scope of traditional public health activities” (CDC, 2016). Using this approach means that every federal policy has potential population health implications that need to be considered when evaluating it for health equity.

- Evidence is informed by quantitative, qualitative, and community sources.

The committee used an inclusive (standards of) evidence approach. This meant drawing from both quantitative and qualitative historical and contemporary evidence from peer-reviewed sources and nonpartisan research organizations across disciplinary perspectives. The committee paid particular attention to community-informed research approaches that are often not included in the evidence base to inform, implement, or evaluate policy. Each of these sources of evidence should be valued and evaluated in building the knowledge base, which should be evaluated from a fundamental cause of disease approach,5 focusing on structures and systems versus individual- or community-level actions as the causes of health inequities. This approach requires reviewing other factors that impact health equity, including the intersections of systems of stratification across, but not limited to, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, class, and ability. It also allows for evaluating the impact of policies (or absence of policies) on multiple domains of mental, physical, and behavioral health and well-being across diverse groups.

- Center health equity in all federal policies.

The committee centered equity in every step of evaluating federal policies and developing recommendations for future policy assessment and

___________________

5 Using a fundamental cause of disease approach means that individually based risk factors need to be contextualized by examining what puts people at risk of risks; social factors, such as socioeconomic status and social support, are considered “fundamental causes” of disease that “because they embody access to important resources, affect multiple disease outcomes through multiple mechanisms, and consequently maintain an association with disease even when intervening mechanisms change” (Link and Phelan, 1995, p. 80).

creation. Centering equity means prioritizing the needs of racially and ethnically minoritized populations and considering the consequences of current and future policies for advancing or impeding health equity. Multiple tools exist to assess current policies for equity and project the impacts of future policies (for example, see Ashley et al., 2022; Martin and Lewis, 2019; MITRE, n.d.; OMB, 2021; Urban Institute, n.d.).

Although a cost–benefit analysis of policies is beyond the scope of the report, centering equity also requires affirmatively advancing civil rights, racial justice, and equal opportunity as key structural, political,6 and social determinants of health; elevating community experience, voice, and expertise; and using that voice to inform policy. Tensions and tradeoffs exist (e.g., prioritizing equity over efficiency, recognizing that communities are diverse and can have opposing views and needs, respecting data sovereignty, and making data available to the public) when working with diverse communities. However, multiple evidence-based processes have been established for collective decision-making processes across groups with diverse identities and views (e.g., public deliberation) (Blacksher et al., 2021; Bose et al., 2017; Christiano, 1997).

The committee centered equity when examining structures and systems in understanding impacts of policies on health inequities, with two subprinciples.

(4a): Eliminate and prevent harm: When evaluating current policies across multiple domains, the committee first identified characteristics of federal policies or their implementation that are maintaining, causing, or amplifying racial/ethnic health disparities either directly or indirectly, as measured by available evidence. The committee’s focus on eliminating and preventing harm was strongly informed by the precautionary principle in environmental science, which contains four principles: (1) taking preventive action in the face of uncertainty, (2) shifting the burden of proof to the proponents of a policy, (3) exploring a wide range of alternatives to possibly harmful actions, and (4) increasing public participation in decision making (Kriebel et al., 2001). In some situations, elimination may not be possible but mitigation can reduce harm and prevent further harms.

(4b): Maximize potential for equity: Policies were evaluated with an eye toward achieving health equity. The committee acknowledges that removing harm, reducing disparities, and/or improving health capacities are necessary first steps; reducing disparities is not the end goal.

___________________

6 “Political determinants of health involve the systematic process of structuring relationships, distributing resources, and administering power, operating simultaneously in ways that mutually reinforce or influence one another to shape opportunities that either advance health equity or exacerbate health inequities” (Dawes, 2020, p. 44).

- Structural and systems change are needed to advance health equity.

Achieving health equity will require structural and systems changes. This means that not only must policies address structure and create systems change but also the structure and components of policies need to be interrogated and also potentially changed. Because of this, the committee used an approach where the sum of policy parts is greater than the whole. It is often said that, “The whole is greater than the sum of the parts,” but this may not always be the case for policies. They have multiple components as they relate to setting and prioritizing objectives; coordinating policy and implementation; and monitoring, analysis, and evaluation. Even well-intentioned policies aimed at improving well-being can have a negative impact based on how they are created, implemented, or monitored. Policies targeted at low-income people, for example, may impose higher levels of administrative burden (e.g., complex, opaque, rigid, or repetitive requirements) than services more likely to be universal (OMB, 2021). Later chapters show, for example, how eligibility criteria or lack of enforcement can turn health-promoting into health-harming policies, particularly for racially and ethnically minoritized populations, creating health inequities.

Approach to the Report and Recommendations

The task provided to the committee was extremely but necessarily broad—review federal policies that contribute to racial, ethnic, and tribal inequities. The number of factors that contribute to health inequities are large and fall in many domains (see Figure 1-2 and Box 1-1). At its first meeting, Rear Admiral (RDML) Felicia Collins, director of OMH (the sponsor of this report), provided the charge to the committee. She was clear that the charge included reviewing all the SDOH but left it to the committee to determine how to approach its task and what to include in its review. RDML Collins also requested that the committee use the Healthy People 2030 SDOH framework. The committee could not review every federal policy and program that might contribute to racial, ethnic, and tribal health inequities within the five SDOH domains in the year it had to develop its report. For example, Congress has enacted hundreds of statutes during each of its 118 biennial terms and more than 30,000 statutes since 1789, and federal agencies each have numerous policies under their authority (GovInfo, n.d.; Govtrack, n.d.).

To focus its review to best achieve the Statement of Task, the committee took a multi-phased approach: gathering information, developing criteria for selecting policies to review, and reviewing prioritized policies.

For information gathering, the committee reviewed the published literature (including grey literature), held information-gathering meetings (see Appendix B), put out a call for public input (including lived experiences), and reviewed key policies in each of the five SDOH domains (see Chapters 3–7).

To identify the federal policies reviewed in this report, the committee developed the following set of considerations for prioritization. First, prioritize policies that impact a large percentage of minoritized racial or ethnic populations. Second, prioritize policies that have a body of literature or available data to assess them based on race and ethnicity. Third, prioritize historical policies that, based on the literature, continue to harm racially and ethnically minoritized and tribal populations. Fourth, given that data gaps for racially and ethnically minoritized and tribal populations are a well-documented problem (see Chapter 2), prioritize policies that illustrate how these data gaps could fail to document health inequities. Finally, the committee also prioritized expertise from itself and invited speakers, verbal public comments at information-gathering meetings, and written public comments (see Appendix B and Box 1-7). Based on a mix of these considerations, the committee used its expert judgment to choose the federal policies to review in the following chapters. The review examined how the policy affected (both positively and negatively) racial, ethnic, or tribal health equity.

Based on its review, the committee was able to identify aspects of federal policy that cut across domains and contribute to health inequities or could advance health equity. These crosscutting themes formed the foundation of the report recommendations, with the key principles as a guide (see Box 1-5), When the committee identified barriers to health equity for a specific federal policy, if the literature reviewed promising or evidence-based solutions, the committee provided a discussion of those solutions (the committee was asked in its Statement of Task to review both promising and evidence-based solutions—see Box 1-3). The committee is not unique in its approach to recommendations. The Federal Plan for Equitable Long-Term Recovery and Resilience (ELTRR) (November 2022) also lays out a crosscutting approach and recommendations for federal agencies to cooperatively strengthen the vital conditions necessary for improving individual and community resilience and well-being nationwide (see the next section for more information) (ELTRR Interagency Workgroup, 2022).

Although the committee had to make difficult decisions regarding which policies to highlight, omitting a particular policy does not mean it is any less important. The committee focused on those policies (or lack thereof in a given area) that would best illustrate how policies (or particular components) can hinder or advance racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity. The committee applied the key principles and concepts and took into account the important interplay between federal policy with states, tribes, territories, and localities and the policy tools available at the federal level (see Chapter 2 for more on this topic). Similarly, many painful historical actions, practices, policies, and laws have led to trauma for specific groups in relation to federal policy; this report could not cover them all.

An abundance of high-quality evidence-based and peer-reviewed reports, from the National Academies and other evidence-based organizations,

has either laid out the evidence for the root causes and mechanisms of health inequities or provided actionable recommendations for specific policy actions that could be taken to change federal policies to advance health equity (for example, see, IOM, 2003a, 2003b; IOM and NRC, 2013; NASEM, 2017, 2018a, 2018b, 2019a, 2019b, 2019c, 2019d, 2019e, 2021a, 2021b, 2022a, 2022b, 2022c, 2022d, 2022e). The committee builds off of this work and looks to the future, rather than repeating existing analysis. The committee also provides recommendations from other reports that have not been acted on and endorses them because they still merit attention and action. In addition, other National Academies studies in progress or recently released overlap with the committee’s charge, so the committee focused more on policies not covered by those reports (for example, the Committee on Unequal Treatment Revisited: The Current State of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare,7 the Committee on the Review of Policies and Programs to Reduce Intergenerational Poverty,8 and the 2023 report Closing the Opportunity Gap for Young Children [NASEM, 2023a]).

As noted in the guiding principles, the committee focused on identifying institutional- and structural-level factors that impact population health. Therefore, it focused its efforts on providing recommendations on crosscutting approaches that would impact a wide range of policies (see Chapter 8). Per the guiding principles, the committee considered policies that leave populations that have been racially and ethnically minoritized behind, cause harm, undermine civil rights, racial justice, and equal opportunity, omit community voice and evidence, and/or do not consider health equity. It provides recommendations at both the institutional (for example, addressing administrative burden across programs) and structural (for example, addressing accountability) levels. The committee does provide select policy-specific recommendations (it focused on those policies most proximal to health outcomes, such as health care access and quality).

This report focuses mainly on the U.S. 50 states, but racial and ethnic groups that have been minoritized live in U.S. territories as well. The territories’ governing systems vary—for example, individuals born in Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Guam, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands are U.S. citizens, and those born in American Samoa are U.S. nationals. Their eligibility for federally subsidized programs varies by territory and program. Residents of all five territories may participate in Medicaid, CHIP, Medicare, and Social Security, but

___________________

7 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/unequal-treatment-revisited-the-current-state-of-racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-healthcare (accessed March 7, 2023).

8 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/policies-and-programs-to-reduce-intergenerational-poverty (accessed March 22, 2023).

none except those in CNMI is eligible for Supplemental Security Income (MACPAC, 2021). Addressing health equity in U.S. territories is important, and the report provides several examples of how federal policy varies in territories; however, the necessary deep analysis is beyond the scope of this report.

CURRENT LANDSCAPE

Advancing health equity (or equity in areas that impact health, such as the environment, housing, and economic well-being) has garnered much attention recently from philanthropies, nonprofit organizations, and federal, state, and local governments. The following section summarizes some of these efforts. The committee strived to build off these and other existing efforts and analyses in its report.

Executive Orders

The most relevant executive order Executive Order (EO) is 13985,9 Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government (January 2021). It notes that “equal opportunity is the bedrock of American democracy, and our diversity is one of our country’s greatest strengths” but that entrenched inequities in U.S. law and policy (and private and public institutions) have “denied that equal opportunity to individuals and communities.” The EO called on the Domestic Policy Council to coordinate the efforts outlined in the EO and embed equity principles, policies, and approaches across the federal government in coordination with the National Security Council and National Economic Council (see Box 1-6). Although the EO does not explicitly

___________________

9 Exec. Order No. 13985, 86 FR 7009 (January 2021).

state “health” equity as its goal, the proposed actions span all federal agencies. As discussed, health equity is impacted by a large range of factors, including economic stability and access to housing and a safe environment—and therefore the EO is strongly tied to health. OMB was tasked with partnering with agency heads to study methods for assessing whether agency policies and actions create or exacerbate barriers to full and equal participation by all eligible individuals (see OMB, 2021). Findings and recommendations from the OMB report highlight that federal programs and services should be viewed through an equity lens. Some of the report findings include the following:

- Bringing together expertise and experience from across sectors can be a powerful catalyst for learning and solutions.

- The federal government can learn from and improve upon existing equity assessments, demographic data collection processes, and tools, particularly models that have supported state and local governments.

- Intersectionality matters—federal policies, grants, and programs should always account for how people’s multiple identities interact with intersecting systems of oppression (OMB, 2021).

To meet the goals of EO 13985, each federal agency was tasked with developing an equity plan within 1 year (agencies released their plans in April 2022, and these are available online)10 (DPC, 2023; The White House, 2022a). The EO also highlights the need for “engagement with members of underserved communities” and that the agencies “should consult with members of communities that have been historically underrepresented in the federal government and underserved by or subject to discrimination in federal policies and programs.” Another major aspect of the EO was establishing the Equitable Data Working Group (see Chapter 2 for more information) (Equitable Data Working Group, 2022). A follow-up EO (14091)11 was issued on February 16, 2023, stating that federal agency and department Equity Action Plans will be updated annually and that each agency and department will designate and provide resources to Agency Equity Teams for implementation. The updated EO also adds increased requirements for engagement with and investments in impacted communities, addresses emerging risks from technology, and continues data equity and transparency efforts (The White House, 2023). The EO and resulting efforts are discussed throughout this report, with several key initiatives and OMB findings outlined in Chapter 8.

___________________

10 See https://www.whitehouse.gov/equity/#equity-plan-snapshots (accessed March 15, 2023).

11 Exec. Order No. 14091, 88 FR 10825 (February 2023).

Other relevant EOs have been created by the current and past administrations:

- 13175 (November 2000), Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments12

- 13995 (January 2021), Ensuring an Equitable Pandemic Response and Recovery, which called for establishing a Presidential COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force13,14

- 14008 (January 2021), Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad15

- 14031 (May 2021), Advancing Equity, Justice, and Opportunity for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders16

- 14050 (October 2021), White House Initiative on Advancing Educational Equity, Excellence, and Economic Opportunity for Black Americans17

- 14053 (November 2021), Improving Public Safety and Criminal Justice for Native Americans and Addressing the Crisis of Missing or Murdered Indigenous People18

- 14070 (April 2022), Continuing to Strengthen Americans’ Access to Affordable, Quality Health Coverage19

- 14075 (June 2022), Advancing Equality for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Individuals20

Other Federal Government Reports, Initiatives, and Background

One example of a federal initiative to advance health equity is Opportunity Zones. EO 13853, signed by President Trump, established the White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council to carry out the administration’s

___________________

12 This order established regular and meaningful consultation and collaboration with tribal officials to develop federal policies that have tribal implications, strengthen the U.S. government-to-government relationships with Indian tribes, and reduce the imposition of unfunded mandates. Exec. Order No. 13175, 65 FR 67249 (November 2022)

13 Exec. Order No. 13995, 86 FR 7193 (January 2021).

14 Recommendations from the task force included (1) invest in community-led solutions to address health equity, (2) enforce a data ecosystem that promotes equity-driven decision making, and (3) increase accountability for health equity outcomes. Its accountability framework highlighted that (1) community expertise and effective communication needs to be elevated in health care and public health; (2) data should accurately represent all populations and their experiences to drive equitable decisions; and (3) health equity should be centered in all processes, practices, and policies (Presidential COVID-19 Health Equity Task Force, 2021).

15 Exec. Order No. 14008, 86 FR 7619 (January 2021).

16 Exec. Order No. 14031, 86 FR 29675 (May 2021).

17 Exec. Order No. 14050, 86 FR 58551 (October 2021).

18 Exec. Order No. 14053, 86 FR 64337 (November 2021).

19 Exec. Order No. 14070, 87 FR 20689 (April 2022).

20 Exec. Order No. 14075, 87 FR 37189 (June 2022).

plan to target, streamline, and coordinate federal resources to be used in Opportunity Zones and other economically distressed communities (Opportunity and Revitalization Council, 2019).

Another example is the Federal Plan for ELTRR released in November 2022 by the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health and the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP), on behalf of an interagency workgroup composed of over 35 federal departments and agencies. The plan was developed “to address the deep disparities in health, well-being, and economic opportunity that were laid bare during the COVID-19 pandemic” (ODPHP, 2022). The workgroup identified opportunities for collaboration to maximize available resources across government agencies and improve community resilience21 with the vision of “all people and places thriving, no exceptions.” The plan uses the seven “Vital Conditions for Health and Well-Being” as the guiding framework. The vital conditions are the following:

- Belonging and Civic Muscle

- Thriving Natural World

- Basic Needs for Health and Safety

- Humane Housing

- Meaningful Work and Wealth

- Lifelong Learning

- Reliable Transportation

The vital conditions align with the Healthy People 2030 five SDOH categories that the committee used to guide its work (see Committee Approach section). This effort began during the Trump administration, ended during the Biden administration, and has been embraced by federal agencies (see Chapter 7). The plan includes 78 recommendations for interagency action and maps out how federal entities can connect through mutual interests and existing authorities. Most recommendations tie to a specific vital condition; 10 address crosscutting infrastructure and governance.

Another example of a government initiative related to health equity is Justice 40, a whole-of-government initiative with the goal “that 40 percent

___________________

21 Key actions for the plan include (1) align federal government departments and agencies to strengthen the Vital Conditions for Health and Well-Being; (2) foster community-centered collaboration within and outside of government to ensure an equitable, thriving future; (3) adapt steady-state and other federal investments within agency authority to transform systems that enable resilience and well-being; and (4) achieve equity and aspire to eliminate disparities by focusing sustained resources on communities that have been underserved or disadvantaged. The next steps include (1) form an executive steering committee, (2) retain the ELTRR Interagency Workgroup, (3) establish a measurement framework and indicators, (3) systematically link plan efforts to related executive orders and priorities, (4) leverage regional expertise and networks, and (5) engage with and gather input from nongovernmental partners (ELTRR Interagency Workgroup, 2022).

of the overall benefits of certain federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution” stemming from EO 14008 (The White House, 2022b). The current administration has also taken a whole-of-government approach to addressing climate change.

The federal government’s focus on health equity is also evident in a January 2021 report: Something Must Change: Inequities in U.S. Policy and Society (U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means, 2021b). It examines how racism, ableism, and other social, structural, and political determinants negatively impact health and economic equity. On March 4, 2021, the chair of the committee announced the creation of its Racial Equity Initiative to “address the role of racism and other forms of discrimination in perpetuating health and economic inequalities in the United States” to build on the framework A Bold Vision for a Legislative Pathway Toward Health and Economic Equity that the committee also issued in January 2021 (U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means, 2021a, n.d.).

Several ongoing court cases also could have significant impacts on health equity, including the unfolding effects of overturning Roe v. Wade,22 and Braidwood Management v. Becerra23 (on Affordable Care Act [ACA] coverage of services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force24), which could have important implications for coverage with $0 cost sharing for preventive health care services. A relevant recent case is Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College,25 which ended race-based considerations in higher education, including in medical school and other health professions school admissions. Another recent case, Haaland v. Brackeen (the Indian Child Welfare Act),26,27 could have had major consequences for both tribes’ right to exist as political entities and family separation—however, the law was upheld with the June 15, 2023, Supreme Court decision.

___________________

22 Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113.

23 Braidwood Management Inc. v. Xavier Becerra, 4:20-cv-00283, (N.D. Tex.).

24 Under Section 2713 of ACA, self-funded health plans and insurers offering nongrandfathered group or individual market health plans must cover services given an “A” or “B” rating from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–recommended vaccines, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)–recommended preventive care and screening recommendations for children, and HRSA Women’s Preventive Services Initiative–recommended services, including contraceptives (Child Welfare Information Gateway, n.d.).

25 Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard College 600 U.S. ____ (2023).

26 Haaland v. Brackeen (Docket No. 21-376).

27 The Indian Child Welfare Act is a 43-year-old federal law that protects the well-being and best interests of Indian children and families by upholding family integrity and stability and keeping children connected to their community and culture and affirms the tribal sovereignty of First Nations.

STUDY PROCESS AND REPORT OVERVIEW

Information-Gathering Process

The committee gathered information in a variety of ways. It held three information-gathering sessions between June and September of 2022 (agendas are available in Appendix B; all meetings were virtual) on a range of topics, including racial and ethnic health inequities; socioeconomic differences in health; housing, transportation, and health policy; federal Indian law and constitutional law; community infrastructure challenges and solutions; policy levers; and interagency collaboration. In addition, the committee held two public comment sessions to solicit feedback on key questions that broadly asked about the impacts, both positive and negative, of health policies and their effects on health equity and the lived experiences of racially and ethnically minoritized groups. The committee held deliberative meetings and received public submissions of materials throughout the study.28 The committee made a call for public comments via the project website (see Box 1-7 for a summary of topics raised), listserv, and outreach to relevant organizations. Its online activity page also provided information to the public about its work and facilitated communication with the public.29

Report Overview

Throughout this report, the committee provides conclusions, and the report ends with recommendations for action, guided by the conceptual framework and guiding principles introduced in this chapter. The committee organized its recommendations under four core action areas to advance racial, ethnic, and tribal health equity:

- Implement Sustained Coordination Among Federal Agencies

- Prioritize, Value and Incorporate Community Voice in the Work of Government

- Ensure Collection and Reporting of Data Are Representative and Accurate

- Improve Federal Accountability, Enforcement, Tools, and Support Toward a Government That Advances Optimal Health for Everyone

These themes are explored in detail in the following chapters. Chapter 2 provides an overview of the state of health inequities and of some of the underlying structural determinants and contextual factors that have led to these outcomes. It also describes the role of data collection, shortcomings of the data system, opportunities for improvement to advance federal policy, and

___________________

28 Public access materials can be requested from PARO@nas.edu.

29 See http://nationalacademies.org/health-equity-policies (accessed September 22, 2022).

an overview of the role of government in policy making. Chapters 3–7 cover federal policies in a specific SDOH area—each providing an overview of its connection to health outcomes and inequities and then reviewing specific past or current policies that have implications for health equity. Chapter 3 reviews economic stability and focuses on income, poverty, wealth, and financial services. Chapter 4 reviews levers for federal engagement in early childhood, K–12, and higher education. Chapter 5 reviews health care access and quality by exploring the role of federal programs and policies, such as Medicaid, IHS, value-based payment, and issues around the health care workforce, health literacy, and maternal health. Chapter 6 reviews the neighborhood and built environment and federal policies related to housing insecurity and segregation, disinvestment in infrastructure and the built environment, environmental exposures that threaten health outcomes, particularly in the workplace, and food access and production. Chapter 7 examines social and community context and covers a number of historical and current federal policies that have led to trauma and healing, the criminal legal system, and belonging and civic infrastructure. Finally, Chapter 8 provides recommendations for action organized by the four action areas, with the goal of not only increasing access to important programs but also improving the effectiveness and coordination of government programs and policies.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

Recent attention given to racial, ethnic, and tribal health inequities across sectors and all levels of government suggests this report is being released during a time of policy interest in the committee’s findings,

conclusions, and recommendations. However, the committee’s exploration of the complexities of the challenge makes it clear that although successful advances have been made over time, eliminating these health inequities will take concerted effort, commitment, and action sustained over decades. Implementing the committee’s recommendations will be a powerful first step to meeting this critical challenge.

REFERENCES

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2021. ACOG committee opinion no. 827: Access to postpartum sterilization. Obstetrics & Gynecology 137(6):169–176.

Alexander, W. D. 1899. A brief history of the Hawaiian people. New York, NY: American Book Company.

Angley, M., C. Clark, R. Howland, H. Searing, W. Wilcox, and S. H. Won. 2016. Severe maternal morbidity. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Bureau of Maternal, Infant, and Reproductive Health.

APHA (American Public Health Association). 2021. Analysis: Declarations of Racism as a Public Health Crisis. https://www.apha.org/-/media/Files/PDF/topics/racism/Racism_Declarations_Analysis.ashx (accessed June 13, 2023).

Aragones, A., C. Zamore, E. Moya, J. Cordero, F. Gany, and D. Bruno. 2021. The impact of restrictive policies on Mexican immigrant parents and their children’s access to health care. Health Equity 5(1):612–618.

Ashley, S., G. Acs, S. Brown, M. Deich, G. MacDonald, D. Marron, R. Balu, M. Rogers, M. McAfee, J. Kirschenbaum, T. Ross, A. Gardere, and S. Treuhaft. 2022. Scoring federal legislation for equity: Definition, framework, and potential application. Washington, DC: Urban Institute and PolicyLink.

Bailey, Z. D., N. Krieger, M. Agénor, J. Graves, N. Linos, and M. T. Bassett. 2017. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet 389(10077):1453–1463.

Blacksher, E., V. Y. Hiratsuka, J. W. Blanchard, J. R. Lund, J. Reedy, J. A. Beans, B. Saunkeah, M. Peercy, C. Byars, J. Yracheta, K. S. Tsosie, M. O’Leary, G. Ducheneaux, and P. G. Spicer. 2021. Deliberations with American Indian and Alaska Native people about the ethics of genomics: An adapted model of deliberation used with three tribal communities in the United States. AJOB Empirical Bioethics 12(3):164–178.

Blackwell, A. G. 2016. The curb-cut effect. Stanford Social Innovation Review 15(1):28–33.

Bose, T., A. Reina, and J. A. R. Marshall. 2017. Collective decision-making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 16:30–34.

Brookings Metro, and NAACP. n.d. The Black Progress Index. https://www.brookings.edu/interactives/black-progress-index/ (accessed March 6, 2023).

Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. 2005. Report Evaluating the Request of the Government of the Republic of the Marshall Islands Presented to the Congress of the United States of America. https://2001-2009.state.gov/p/eap/rls/rpt/40422.htm (accessed June 13, 2023).