Future Directions for Southern Ocean and Antarctic Nearshore and Coastal Research (2024)

Chapter: 6 Essential Capabilities

6

Essential Capabilities

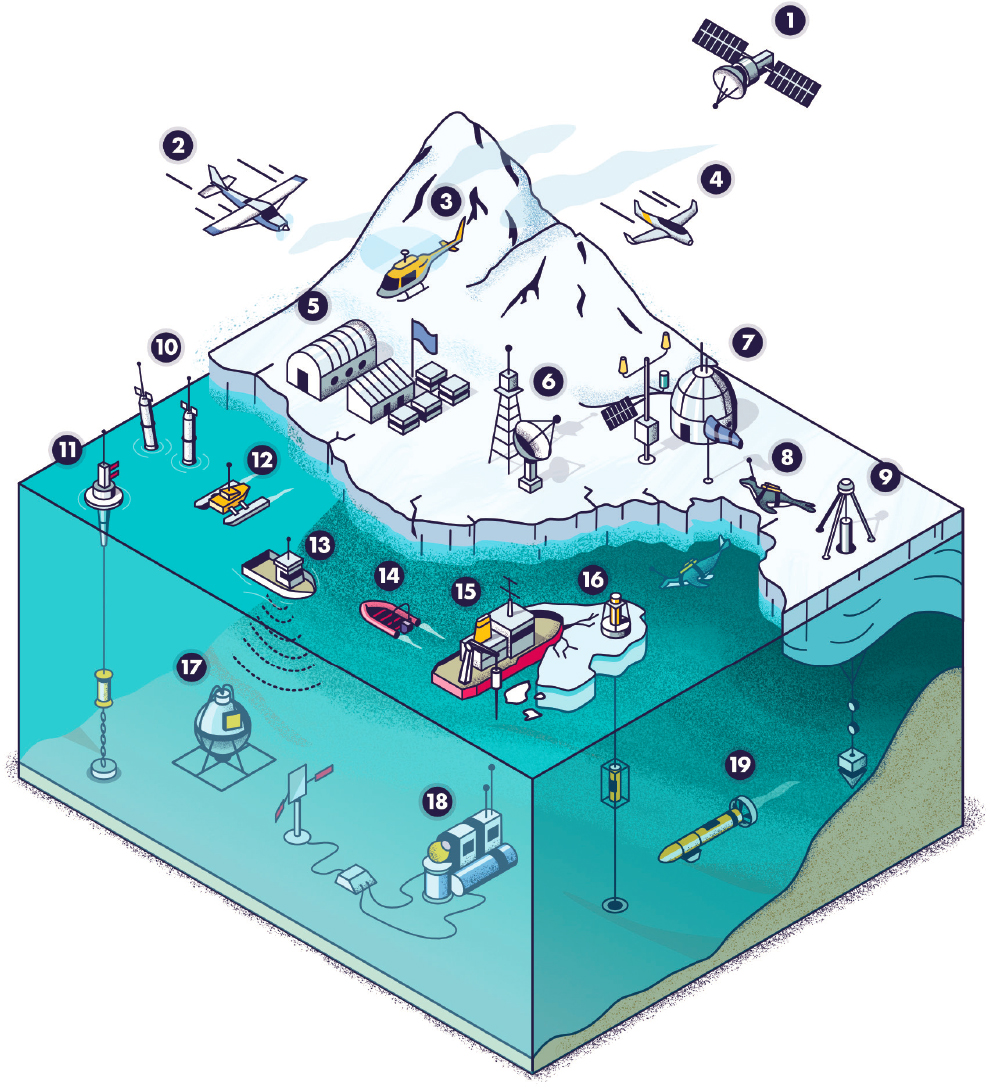

Sustained investment in the science drivers identified in Chapters 3, 4, and 5 will advance U.S. scientific, workforce development, and economic interests. These science drivers, which all have global implications and high societal impact, include more accurate projections of sea level rise, better constraints on future changes to heat and carbon budgets, and a better understanding of the magnitude and rates by which Southern Ocean and Antarctic ecosystem services are expected to change. Increased investments in infrastructure and research programs are required to answer these questions and maintain a robust research program commensurate with other Treaty nations. The study of remote areas around Antarctica—ice, land, and ocean—will require an icebreaking vessel, access to global and local remote sensing data, airborne access for sampling coastal areas and floating ice, and year-round bases with modern laboratories. Since the heterogeneity and geographic scope of Antarctic research stretches beyond any single national program, partnerships are necessary for logistical success, and the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) must be flexible and creative in its approach to project funding to maximize benefits and minimize costs.

This chapter summarizes the essential capabilities identified in previous chapters and their availability to U.S. researchers (Figure 6-1). These capabilities include those hosted on USAP platforms, including the preliminary design of the Antarctic Research Vessel (ARV); those that are enabled by emerging tools and technologies; and specific programmatic approaches and partnerships that will advance and accelerate research. The final section of this chapter identifies gaps between capabilities and those required by the research priorities in Chapters 3, 4, and 5, and identifies several recommendations that would allow the United States to address those gaps.

VESSEL CAPABILITIES

As described in Chapter 2, both current USAP vessels—the Nathaniel B. Palmer and the Lawrence M. Gould—are approaching or have exceeded their roughly 30-year design service. The science priorities outlined in Chapters 3, 4, and 5 justify the need for large investments in a new USAP icebreaker. Below, high-priority vessel capabilities needed by U.S. researchers are identified. Where it is not practical to include these capabilities on a new USAP vessel, potential opportunities to access these capabilities through partner organizations or commercial arrangements are discussed. However, most partner organization resources are committed many years in the future and have planning horizons that are not well aligned with current National Science Foundation (NSF) processes. Given that reality, direct U.S. investments in infrastructure are strongly preferred to a reliance on partnerships,

as these investments will provide U.S. researchers the opportunity to drive research forward without external constraints, maintain leadership positions in the international polar community, support a well-trained future U.S. workforce, and engage as equal decision-making partners in the design and implementation of future international field programs. These investments in U.S. capabilities will strengthen U.S. scientific, workforce development, and economic interests both nationally and abroad.

NSF may need to consider trade-offs between vessel capabilities. To assist NSF in this effort, the committee classified capabilities needed by the U.S. researchers on USAP or partner vessels as Critical or Important for each of the science drivers (Table 6-1). The justifications for these classifications are expanded in the sections below. Where appropriate, the text references back to the more comprehensive justifications provided in Chapters 3, 4, and 5.

Polar Class 3 Icebreaking Capabilities

A Polar Class 3 (PC3) icebreaker for access into winter ice cover and to coastal areas is Critical for studies on sea level rise, global heat and carbon budgets, and changing ecosystems (see Chapters 3, 4, 5; Table 6-1). Specifically, a PC3 icebreaker would enable improved understanding of nearshore and winter processes such as sea ice production, dense shelf water production, oceanic forcing of Antarctic ice shelves, water mass modification in polynyas, and ecosystem processes on sea ice and in coastal polynyas (Chapters 3, 4, 5; Table 6-1). This access to the coast across all seasons is also essential for deploying other capabilities such as ice stations (e.g., Ackley et al., 2020), and emerging autonomous platforms and drifting platforms capable of operation in ice-covered waters and within ice shelf cavities.

TABLE 6-1 Critical (C) and Important (I) capabilities for U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) or Partner Vessels for the Three Science Drivers Identified in this Report

| Capabilities on USAP or Partner Vessels | Sea Level Rise | Global Heat and Carbon Budgets | Changing Ecosystems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polar Class 3 icebreaking capabilities | C | C | C |

| Endurance: >70 days summer and >50 days winter icebreaking | I | C | I |

| Full helicopter support | C | I | I |

| Ability to launch and recover uncrewed aerial systems | I | C | C |

| Ability to launch and recover large uncrewed underwater vehicles | C | C | C |

| Moonpool | I | ||

| Zodiacs, rigid inflatable boats, and other small boats associated with an icebreaker | I | C | C |

| Hull-mounted sensors (e.g., shipboard sonar, scientific echosounder, and sub-bottom profiler) | C | C | C |

| Towed sampling and instrumentation (magnetic, multichannel seismic, underway profiling CTD packages, controlled-source electromagnetics, nets) | I | C | C |

| Seafloor and submarine sampling (e.g., coring, drilling, dredging, seafloor or borehole observatory) | C | C | C |

| Live organism experiments (aquarium facilities, incubators, running seawater) | C | ||

| Low-temperature storage | I | C | |

| >45 berths for science and support staff | I |

NOTES: The most crucial capabilities are Critical, with Important and blank cells indicating lesser importance. CTD = conductivity, temperature, and depth.

The ARV is currently designed as a PC3 vessel with the nominal capability to transit continuously through level ice over 1.3 m (4.5 ft) thick at more than 3 knots (Antarctic Support Contractor, 2023). The Nathaniel B. Palmer is approximately equal to a PC5 or PC4, with year-round operation limited to medium first-year ice. In practice, the Nathaniel B. Palmer icebreaking capabilities are limited, particularly in winter and in areas where there is extensive ridging, deep snow cover, and significant ice pressure. For example, historically, the Nathaniel B. Palmer has been limited to regions of the outer pack in midwinter in the Ross and Bellingshausen seas (e.g., Jeffries et al., 1998). In early autumn, ice pressure has limited travel even through thin ice (Ackley et al., 2020). Even in summer, access to some areas of critical concern (e.g., the western Bellingshausen Sea and the Amundsen Sea Embayment) is not always possible with the Nathaniel B. Palmer.

An analysis of icebreaking capability based on ice charts (Future USAP, 2023b) suggests a PC3 vessel would be able to access practically all areas around the Antarctic year-round, with the potential exceptions of areas where perennial ice is common. This analysis is likely optimistic, as ice charts do not account for ridging extent or amount of snow cover, so areas that are prone to particularly heavy ridging or deep snow may still present challenges in winter for a PC3 vessel. It seems likely that many coastal regions will remain challenging to access in winter, particularly the western Weddell, southern Bellingshausen, Amundsen, and eastern Ross seas, as well as parts of the East Antarctic coastline. However, winter access to the Antarctic coast will likely now be possible in the Ross Sea and eastern Weddell Sea, and critically, access to almost all areas will be feasible in summer (with the possible exception of limited areas of the western Weddell Sea). This is likely a reasonable trade-off, as a PC3 will offer better access than the current capability of the Nathaniel B. Palmer (PC5/PC4), while the added operational expense and design constraints of a PC1 or PC2 vessel are difficult to justify solely for access to those few regions that may be challenging outside of the summer season. In those rare circumstances where access through extreme ice conditions is required, it would be more economical to partner with one of the Coast Guard’s Polar Security Cutters or another nation’s heavy icebreaker.

Some observations of ice and ocean processes in difficult-to-access regions during winter are possible via alternative platforms, including in situ autonomous observations and a variety of moored platforms and drifting platforms and floats (including ice-tethered platforms and biogeochemical Argo [BGC-Argo] floats). However, these approaches currently require vessel support for deployment and recovery, and few are well suited for deployment in coastal regions. Long-range autonomous underwater vehicles and gliders capable of operating under ice for extended periods are emerging technologies (e.g., Barker et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2022), although long endurance and range capabilities come at the expense of more limited sensor payload. For the foreseeable future, the only means of access to remote, ice-covered areas will require icebreaker support. In some cases—for example, deploying observational arrays in heavy ice or various platforms near the front of ice shelves—helicopter support could mitigate access restrictions for a vessel with reduced icebreaking capabilities.

The icebreaking capability of the preliminary design of the ARV would be comparable to the Norwegian Kronprins Haakon, Australian Nuyina, and the Chinese Xue Long 2. The German Polar Stern II and a future Swedish icebreaker are also anticipated to have similar icebreaking capabilities. While several international partners have or are anticipated to have similar icebreaking capability to the ARV, those that typically operate in the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean (Korea, Italy, and the United Kingdom), where the USAP most commonly operates, currently have PC5 capability at most. A PC3 vessel would offer opportunities for joint operation with, for example, South Korea’s Araon and Great Britain’s Sir David Attenborough, leveraging the former’s icebreaking capabilities with the Araon and Sir David Attenborough’s helicopter support capabilities. See Appendix B for the capabilities of these and other ships.

Endurance

Greater endurance is required for periods of extensive icebreaking capability. Thus, greater than 70 days of endurance in the summer and >50 days of endurance during winter icebreaking is classified as Critical for global heat and carbon budgets studies and Important for sea level rise and changing ecosystem studies (Table 6-1). For example, the ability to study Antarctic Bottom Water formation processes in the winter (Chapter 4) would require extensive icebreaking, which would likely require this level of endurance. Longer endurance is also necessary for

USAP access to East Antarctica (Box 6-1). Greater than 70 days endurance in the summer would allow access, for example, to the Totten Glacier in East Antarctica (Chapter 3), as its remoteness would entail significant transit (roughly 8–10 days one way from Hobart, Australia) and still accommodate a 50-day science cruise on site.

Following several prior community reports that called for greater than 80 days of endurance (Chapter 2), the endurance of the ARV is designed for midsummer optimal maximum of 90 days. This means that the ARV may be able to operate for 45–60 days for a midwinter cruise that requires significant icebreaking through areas of extensive ridging, thick snow cover, and greater ice pressure.1

Helicopter Support

The ability for U.S. researchers to have access to two light-duty helicopters on USAP or partner vessels is Critical for access to near-shore areas for studies on sea level rise (Chapter 3; Table 6-1). Identifying and characterizing complex processes driving solid Earth–ice–ocean–atmosphere interactions requires tactical deployment of surface instrumentation, drilling equipment, and associated field camps in coastal areas. Many of the most compelling places to acquire data relevant to sea level rise research—such as fast-flowing glaciers, grounding zones, and ice shelves—are too dangerous or too remote to be accessed by fixed-wing aircraft such as Twin Otters (Figure 6-2). For example, the most rapidly retreating (and arguably the most important to study) section of Thwaites Glacier’s grounding line is heavily crevassed and impossible to land on using fixed-wing aircraft. As a result, the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC) has so far been limited to deploying surface camps on Thwaites’s less dynamic Eastern Ice Shelf, where an airplane could operate safely.2 If ITGC had access to helicopters, it is possible that their hot water drilling efforts, for example, could have enabled robotic exploration of the most rapidly melting part of the Thwaites Glacier Tongue.

Access to USAP or partner vessels with helicopter support is also classified as Important for studies on global heat and carbon budgets and changing ecosystems (Chapters 4, 5; Table 6-1). Deployment of ice-tethered platforms via vessels with helicopter support is a common operation in the Arctic and has also been employed by several Antarctic programs (e.g., Krishfield et al., 2008). Helicopters have also enabled remote surveys of sea ice properties (e.g., Heil et al., 2009). Helicopters further support efficient deployment of buoy arrays and enable sampling on ice floes while freeing up the vessel to conduct other observations. For a complex buoy array, use of a helicopter can save many days of ship time and open access to some otherwise inaccessible areas of heavy ice. Additionally, vessels with helicopter support can aid in reconnaissance and possible access missions (e.g., facilitating heavy-lift operations for access drilling) for the exploration of ecosystems along grounding zones and coastal margins.

A vessel with full helicopter support (including a helideck and hangar to store and service two helicopters) was supported by previous community workshops and reports (ARVOC, 2006; NSF OPP Advisory Committee, 2019; UNOLS, 2011, 2012). Full helicopter support was eliminated from the Conceptual Design of the ARV in 2020 (Glosten, 2021). Key decision drivers for the removal of the helideck were the cost of construction and maintenance; the space required to accommodate the helideck, hanger, and supporting infrastructure; and concerns over the historical cost of supporting helicopter operations on the Nathaniel B. Palmer. Indeed, NSF has noted that the helideck on the Nathaniel B. Palmer has only been used three times in 30 years, although data on the number of projects that initially proposed helicopter work that were rejected or asked to descope the helicopter work due to costs were not available.3 NSF reports that full helicopter support could drive the ARV to be larger, increasing its displacement and operational costs4; however, the committee has not seen a documented technical analysis of the trade-offs. While the exact impacts are uncertain, increasing the size of the ARV could impact seakeeping, speed and fuel efficiency, and icebreaking, among other parameters.5 The current preliminary design of the ARV can host the landing and takeoff of a single helicopter—for example to transport scientists from the ARV to a partner vessel that supports helicopters or to enable transport with land-based helicopters. However,

___________________

1 Presentation to the committee by NSF, March 2023.

2 Presentation to the committee by Keith Nicholls, British Antarctic Survey, March 2023.

3 Presentation to the committee by NSF, March 2023.

4 Presentation to the committee by NSF, May 2023.

5 Presentation to the committee by NSF, March 2023.

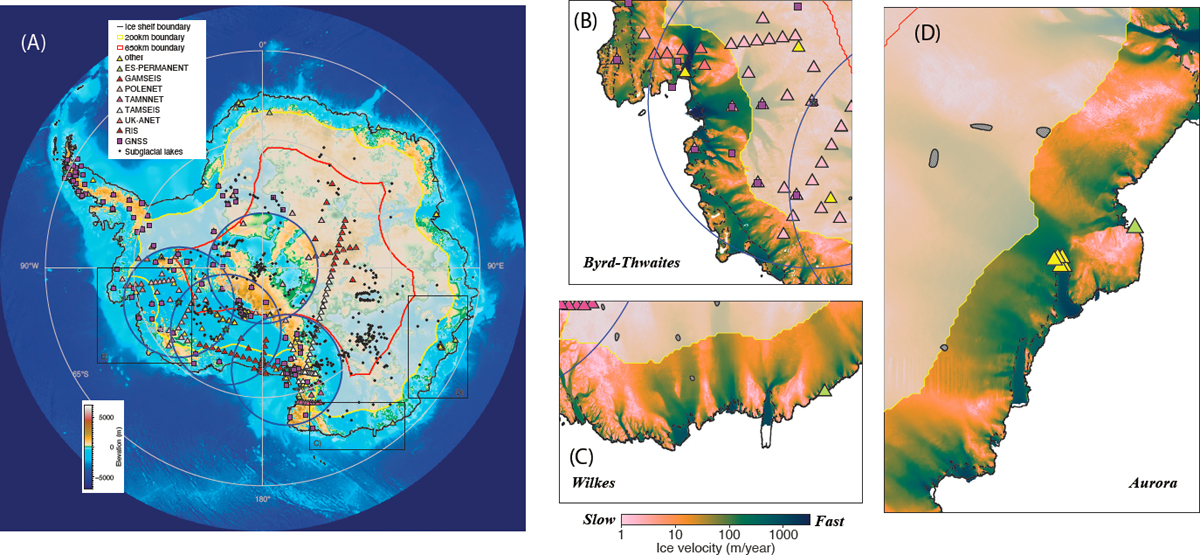

NOTES: Locations of the grounding zone (dashed lines) and subglacial lakes (small contours) are also shown in (b)–(d). Geophysical observational networks deployed by fixed-wing aircraft or on-land traverses, including seismic and GNSS stations, are plotted. The range of fixed-wing-accessible areas assumes a 700 km range of Twin Otters, without refueling on the way, and are based on one of the sites: McMurdo, South Pole, Siple Dome, West Antarctic Ice Sheet divide, and Palmer. Plots of the Byrd subglacial basin and Thwaites glacier area, Wilkes Subglacial Basin area, and Aurora Subglacial Basin areas are also highlighted. ES-PERMANENT = permanent stations with data accessible from the EarthScope Consortium; GAMSEIS = Gamburtsev Antarctic Mountains Seismic Experiment; GNSS = Global Navigation Satellite System; POLENET = Polar Earth Observing Network; TAMSEIS = Transantarctic Mountains Seismic Experiment; UK-ANET = U.K. Antarctic Network; RIS = Seismic Experiment on the Ross Ice Shelf.

SOURCE: Weisen Shen.

it does not provide full support for onboard helicopters without a partner vessel or base (ARV SASC, 2023). It should be stressed that, while access to USAP or partner vessels that support helicopters was judged as Critical for the sea level rise science driver, a potential lack of dedicated helicopter support on the ARV in no way invalidates the critical and important needs for a vessel with icebreaking and science capabilities as outlined in this report. Chapters 3–5 outline national science priorities that fully justify the needs for new science icebreaking capacity in their own right.

U.S. helicopter lease costs on cruises are currently sourced from the Antarctic sciences budget,6 rather than from the logistics budget, which is the practice in many other nations that provided input for this report. NSF estimates that the cost of supporting helicopter operations is approximately $2–3 million per deployment.7 Mobilization and demobilization costs (i.e., transporting the helicopters to and from the port[s] of departure and arrival) and the day rate for long expeditions (even if helicopters are only used part of the time) are the most significant cost drivers, along with jet fuel and extra safety gear.8 In contrast to NSF’s estimate, the committee found that the cost for a Canadian firm to operate two AS-350 helicopters on a 50-day cruise from Lyttelton, New Zealand, with the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) is currently close to USD 330,0009; but comparison of full-cost accounting budgets under various international funding models is beyond the scope of the committee’s task. Further exploration of cost-effective solutions and potential collaborations for helicopter-supported field work would benefit the science drivers in the report.

While helicopters can save many days of ship time and facilitate access to some difficult-to-access locations, this advantage can be partially offset by a vessel with PC3 icebreaking capabilities for sea ice and ocean studies. The ability to deploy small drifting platforms or expendable ocean profilers via uncrewed aerial systems (UASs) is an emergent capability that warrants investment in engineering. However, for most sensor modalities in or under ice this is not currently feasible, and it may never be practical for some high-value observations requiring complex logistics, such as ice-tethered profiler deployments on fast ice adjacent to ice shelves.

The use of heavy-lift UASs to support ice-based research (e.g., large-scale remote sensing surveys) may also be possible in the future, offering an alternative to crewed helicopters for some applications. This capability is currently best achieved with large, heavy-lift (gas-powered) UASs that can travel well beyond direct line-of-sight piloting. The primary limitation for this capability is regulatory. Enabling this capability on USAP vessels would be important in the absence of helicopter support. There are also several commercial companies developing autonomous aerial vehicles (AAVs) or electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) vehicles with passenger capabilities. Systems under development range from fully autonomous to piloted. Claimed capabilities include ranges of more than 100 km and capacities for up to four passengers (e.g., Joby Aviation). Significant challenges remain for operation in the Antarctic, including required long-ranges, remoteness, landing on uncertain terrain, and regulatory requirements. It is unclear whether future systems that meet the unique challenges of Antarctic operation could also be significantly smaller or cheaper, or have smaller support-personnel requirements than crewed light-duty helicopters. Additionally, it is unclear if they could be supported on the current design of the ARV. For example, current eVOTL aircraft designs (e.g., Joby Aviation, CityAirbus) are comparable in size to traditional light-duty helicopters with limited range. Smaller, unpiloted aircraft (e.g., Ehang) have very limited range. Greater range is possible with fueled AAVs. While it is difficult to predict what AAV capabilities may be possible in a decade or two, significant developments in battery technology (i.e., much greater ranges) and autonomy are needed before operation in remote areas is possible with platforms that are competitive in size, logistics, safety, and range with current traditional helicopters.

Another possible alternative to ship-based helicopter support could be land-based combined fixed-wing and helicopter operations (the latter being necessary in those cases such as heavily crevassed ice shelves where fixed-wing landing is unfeasible). This type of operation has previously been supported by the USAP. For example, in 2012–2013, an expedition to Pine Island Glacier, adjacent to the Thwaites Glacier, involved the establishment

___________________

6 Presentation to the committee by NSF, February 2023.

7 Presentation to the committee by NSF, May 2023.

8 Presentation to the committee by NSF, May 2023.

9 Presentation to the committee by Won Sang Lee, KOPRI, March 2023.

of a camp that included helicopter support. Helicopters were transported by ski-equipped LC-130s operated through McMurdo Station.10 Some of these operations have proved challenging in the past in regions that have poor weather and that are remote from bases. These challenges have led to significant impacts to science projects, with some teams with complex operations reporting month-long delays in departing McMurdo for remote camps (Hansen, 2009; Stewart, 2013).

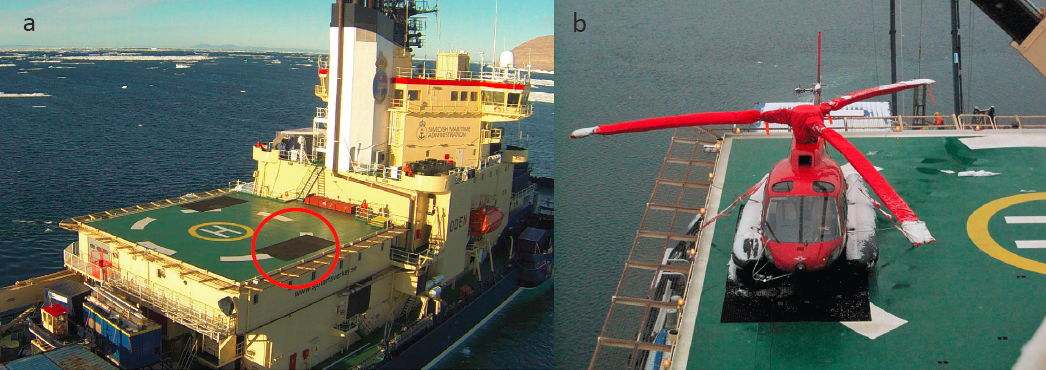

Helicopter support on icebreakers has been prioritized by many international partners (Appendix B). For example, KOPRI’s Araon was initially designed to carry a single, heavy-lift Kamov Ka-32A, but has since adapted to carry either two light-utility AS-350 or Bell 206 helicopters. The Araon operates with a small hangar, thanks to the use of an extendable structure used to protect the aircraft during transit or in inclement weather (Figure 6-3). KOPRI relies on helicopter support on nearly all of their marine voyages; this regular usage has helped them develop practical strategies for efficient use of aircraft and balancing priorities on interdisciplinary expeditions. For example, KOPRI has used their helicopter capacity to tag Weddell seals on all sides of Thwaites Glacier, deploy surface-based GPS and weather stations, collect rock samples from nearby outcrops, install static radar sounders to measure basal melt rates, conduct airborne geophysical surveys, and acquire full-depth ocean profiles between icebergs within 10 km of Thwaites’s grounding line using expendable ocean sensors. KOPRI conducted this level of work in early 2022 during a season in which the icebreaker Araon was unable to gain access within 130 km of Thwaites Glacier.

Other partners that commonly use helicopters on vessel deployments include Australia, China, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators (IAATO), and the U.S. Coast Guard. The Swedish icebreaker Oden commonly uses helicopters but does not routinely operate in Antarctica. The United Kingdom is a common USAP partner and its new vessel, the Sir David Attenborough, is designed to support helicopters (see Appendix B). These partners offer opportunities for collaboration (see section on Collaboration and Partnerships), with partner nations taking advantage of the PC3 icebreaking capability of the ARV and the USAP taking advantage of partners’ helicopter support. However, there are also some potential disadvantages of relying exclusively on international partnerships for helicopter support. These include the added difficulty of facilitating and managing partnerships between scientists and the logistical organizations supporting the intended work, including the necessity to align science priorities between the national programs. The added cost of operating two ships for a single project is another disadvantage of relying on a two-ship model with international partnerships. Building and maintaining international partnerships through individual foreign collaborations can lead to inconsistency across programs and require that the principal investigator (PI) invest substantial time and remain much more flexible than when working solely through the USAP. So-called lead agency agreements11 can facilitate international partnerships by allowing investigators represented by two national programs to submit linked proposals that, if funded, provide clear expectations and points of contact between the two programs. NSF’s Directorate for Geosciences has so far only established lead agency agreements with Germany, Ireland/Northern Ireland, Israel, Switzerland, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom (NSF, n.d.k); more are needed if international partnerships are expected to substitute for a lack of helicopter support on the ARV.

There may be creative solutions to addressing the design challenge that may stop short of the full helicopter support model chosen by other programs for recent ship designs (e.g., Australia, France, China, Norway, United Kingdom) but that could still enable two light-duty helicopters to operate on the ARV. While the committee cannot comment on the engineering design feasibility of these creative solutions, it is possible that discussions with partners about their vessel design may yield ideas that could be incorporated without delaying progression of the ARV through the Final Design Stage. For example, NSF could consider an approach in which the ARV helideck supports two light-duty helicopters without providing a hangar, analogous to the operation of the Swedish icebreaker Oden. Helicopters on the Oden utilize the sides of the helideck for takeoff, landing, and parking (Figure 6-4), which provides sufficient separation for safe operation of the second aircraft. The footprint of the Oden helideck would

___________________

10 Written response from NSF to the committee, April 2023.

11 Lead agency agreements “provide a framework for joint peer review of proposals by two funding agencies in different countries. One organization takes the lead in managing the review process with an agreed level of participation by the other, and both agencies accept the outcome of the review process and fund the costs of the successful applications in their respective countries” (UKRI, 2022, para. 3).

SOURCE: Won Sang Lee.

SOURCE: Alan Mix.

fit approximately within the space provided on the present design of the ARV aviation deck; however, the committee does not have the expertise to comment on the feasibility of adjustments to the side railings and Foremast Instrument Platform to enable safe approaches. Helicopter hangars are used primarily to protect aircraft from sea spray on transits to and from Antarctica or during stormy weather, and to provide a heated space for maintaining the aircraft. The rearward placement of the Oden’s helideck may partially mitigate the impact of sea spray on

transits and in stormy weather, a feature that the ARV would lack with the planned helideck placement on the bow; note, however, that the planned height of the ARV’s helideck is 16 feet higher than the level of the Oden’s helideck (51 ft vs. 35 ft). The committee is not appropriately constituted to comment on the engineering design of the ARV, but engagement with potential helicopter operators and others may assist in evaluating what is feasible.

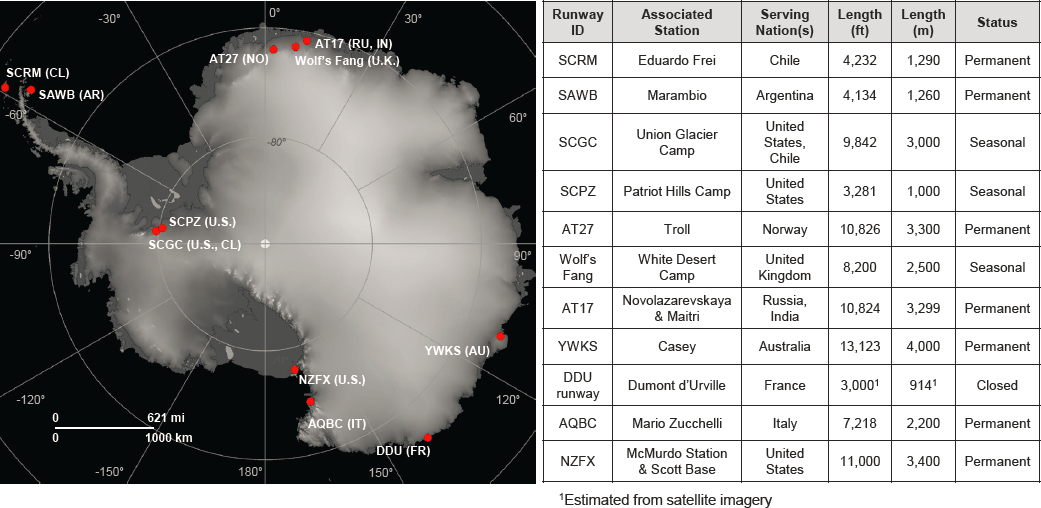

It may be possible for USAP to consider a helideck-only approach thanks to its management of robust intercontinental aviation contracts. The USAP could leverage this unique position to reposition helicopters and their pilots and support staff to and from Antarctica to meet the ARV when needed, thus minimizing marine transits across the Southern Ocean with aircraft exposed to sea spray. The KOPRI represents an existing precedent for this operation. To guarantee uninterrupted helicopter support, KOPRI routinely uses C-130 aircraft to reposition two AS-350 helicopters between Christchurch and Jang Bogo Station in Terra Nova Bay (Figure 6-5). While McMurdo is a natural hub for this type of operation, nine other runways could currently support large, wheeled aircraft such as C-130s and C-17s, which both can carry two helicopters; a tenth optional runway could become available if the French Polar Institute refurbished its Piste du Lion runway facility near Dumont d’Urville Station (Figure 6-6). International agreements for runway access could be particularly compelling, considering the ARV’s long endurance; it is conceivable that within a 90-day cruise window, the ARV could conduct voyages with and without helicopter support if passengers and helicopters could be transported to and from the ARV from one of the participating runways.

NOTE: The Korean Polar Research Institute routinely uses wheeled C-130 aircraft to ferry light-duty AS-350 helicopters to and from Antarctica.

SOURCE: Louis Magnan, Canadian Helicopters Limited.

NOTES: Runway labels are from the International Civil Aviation Organization if available. Some or all of the labeled runways could become staging points for transfers of helicopters and personnel to and from the Antarctic Research Vessel.

SOURCE: Jamin Greenbaum (map). Digital elevation model (DEM) provided by the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center and the Polar Geospatial Center under National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs awards 1543501, 1810976, 1542736, 1559691, 1043681, 1541332, 0753663, 1548562, and 1238993, and National Aeronautics and Space Administration award NNX10AN61G. Computer time provided through a Blue Waters Innovation initiative. DEM produced using data from Maxar.

Ability to Launch and Recover Uncrewed Aerial Systems

The ability to launch and recover UASs is Critical for studies on global heat and carbon budgets and changing ecosystems (Chapters 4 and 5) and Important for studies on sea level rise (Chapter 3; Table 6-1). Specifically, the use of UASs would enable population-trend monitoring of key species and would potentially replace crewed aircraft for most remote sea ice surveys, surveillance for ice navigation, and air–sea interactions.

Several vessel capabilities are needed to support rapidly evolving advancements in robotic platform capabilities, including the ability to support the launch and recovery of UASs with significant payload, ideally while under way (e.g., Zappa et al., 2020). To support full capabilities as this technology evolves, NSF should be prepared to support a variety of platforms, including gas-powered UASs, which may include long-range platforms with large payloads and sizes comparable to ultralight aircraft. This support should also include underway and beyond-line-of-sight operation. For larger systems with significant payload, vessels will require bay space adjacent to the aircraft pad. Some systems may require dedicated teams for operation; the number of berths should factor in the potential need for teams of several support personnel for UAS operation.

The aircraft deck of the preliminary design of the ARV will support most light-duty UASs, including both vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) and fixed-wing platforms. Many longer-range and/or heavier payload systems are VTOL (or nearly VTOL) capable, so that the planned ARV aircraft deck likely will accommodate a large range of UASs. To accommodate future heavy-lift and long-range systems that can perform aerogeophysical surveys, float and buoy deployments, and potentially transport of cargo and/or personnel off the ARV will require consideration of future hangar needs, fueling requirements (gas or potentially hydrogen), and berthing for support personnel. Larger systems may require additional dedicated support personnel and equipment needs, and regulatory certification requirements.

More details about the emerging technologies in UAS can be found under the Tools and Technology section below.

Ability to Launch and Recover Large Uncrewed Underwater Vehicles

The ability to readily launch and recover large uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs, including autonomous underwater vehicles [AUVs], remotely operated vehicles [ROVs], and gliders), autonomous surface vehicles (ASVs), and other underwater/under-ice sensing platforms is Critical for studies on sea level rise, global heat and carbon budgets, and changing ecosystems (Chapters 3, 4, 5; Table 6-1). For large AUV operations, such as the UK National Oceanography Center’s Autosub, significant deck space for dedicated launch and recovery system (LARS) vans is often needed. Many large ROVs also require complex deck operations. Some vehicles have dedicated systems for deployment, while other smaller platforms require aft and/or over-the-side craning capabilities for deployment and recovery. Easy deployment capability for acoustic navigational aids will also benefit AUV operation, including the ability to access a hull instrument well to install an acoustic communication system, to make use of existing well-mounted transducers for such purposes, or to include a dedicated system.

Gliders and many AUVs require accurate buoyancy trimming prior to deployment, which can be done most efficiently off vessels with low freeboard. For most small AUVs (e.g., gliders, REMUS [Remote Environmental Monitoring Units]), deployment and recovery operations using zodiacs, workboats, or rigid inflatable boats increases ease of recovery and reduces risk of damage to the vehicle and its sensors. Zodiacs, workboats, or rigid inflatable boats can also aid in recovery in small open-water areas in ice-covered regions. Alternatively, most medium-sized AUVs and ROVs can be deployed over the side, provided the ship is capable of maintaining open water to the side or aft of the ship. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the capability of the vessel thrusters to provide azimuthal control and flexible thrust to effectively clear ice. Deploying ROVs in loose ice conditions can be challenging because of the need to protect the tether from moving ice. An investigation of whether a dedicated launch-and-recovery system for a variety of small- to medium-sized AUVs and ROVs over the side, or to the aft of the vessel, could be incorporated into the ARV design would be useful. These systems ease operations and mitigate risk of damage to the vehicles. For example, such systems have been used to aid the launch of ROVs through moonpools.

Moonpool

A moonpool is not viewed as essential for most autonomous vehicle operations. As such, access to a moonpool is deemed as Important but not Critical on USAP or partner vessels for studies on global heat and carbon budgets (Chapter 4). A moonpool can offer operational advantages versus over-the-side operation for small- to medium-sized ROVs, including the ability to deploy and recover in all conditions. This generally requires specialized systems for deployment and tether management. Several partner vessels, including the Sir David Attenborough (BAS, 2020) and the Nuyina (Australian Antarctic Division, 2022), have included moonpools with systems for deployment of a variety of equipment in rough conditions and in ice. In some cases, other approaches can be employed for over-the-side UUV deployment, such as armored or protected tethers, and an open-water area can often be maintained to the side of the vessel in continuous, stable ice conditions. However, in more dynamic ice conditions and for some ROV systems, over-the-side operation can be difficult to impossible. A moonpool might also aid in some small AUV deployments, but at present, recovery is generally easier through openings in the ice, potentially aided by zodiacs or rigid inflatable boats. A moonpool can also facilitate acoustic navigation and communication aid deployment in a wide variety of ice conditions.

A second potential use for a moonpool is for CTD deployment. Although this is not a common operation on icebreakers, several partner vessels have been designed to accommodate this. For example, the Nuyina has a moonpool positioned such that the ship CTD can be deployed either over the side or through the moonpool (Australian Antarctic Division, 2023c). To be able to address the science drivers in this report, vessels need to be able to conduct 8-hour CTD operations in ice and rough seas. CTD deployment over the side, even from a dedicated baltic room,12 can be challenging in moving ice conditions or difficult weather. Moving ice conditions can be managed with some effort using the vessel thrusters, while difficult weather can be severely limiting in

___________________

12 A baltic room is a garage for equipment that leads out onto the back deck.

certain wind and wave conditions, such as in the marginal ice zone or in coastal polynyas in winter. A moonpool could allow CTD operations in practically all conditions but would require significant space to accommodate.

Inclusion of an interior midship moonpool on the ARV would come at the expense of laboratory space and/or berthing,13 and although considered potentially useful, did not receive widespread support at the February 2023 Community Workshop. Additionally, it is uncertain whether a moonpool of sufficient size on the aft deck could be accommodated (as has been retrofitted on the Nathaniel B. Palmer for drilling), as it may interfere with the positioning of the propulsion system.14 Concerns about deployment of CTD and UUV in difficult conditions without a moonpool appear to be mitigated in the current ARV design, which includes podded thrusters for better seakeeping, improved ability (relative to the Nathaniel B. Palmer) to maneuver in ice, better load handling on the CTD winch (including articulating arms for deployment), and active heave compensation. These capabilities suggest over-the-side operations will be possible in higher winds, sea state, and more challenging ice conditions than is currently possible on the Nathaniel B. Palmer15 (NSF, 2023d).

Several potential partners’ ships include a moonpool, including the Sir David Attenborough, the Agulhas II, the Nuyina, the Polarstern II (under construction), and a planned future Swedish icebreaker. However, partnerships could only reasonably compensate for the lack of a moonpool on USAP vessels in rare cases, like well-coordinated joint operations. The Nathaniel B. Palmer does have a small moonpool, but since it is accessed on the aft deck (making use difficult for significant operations since it takes potential van space) and is known to get clogged with ice, it has seen limited use. As other nations’ vessels are new or not yet built, it remains unproven how well their moonpools operate under various conditions—particularly in ice.

Zodiacs, Rigid Inflatable Boats, and Other Small Boats Associated with an Icebreaker

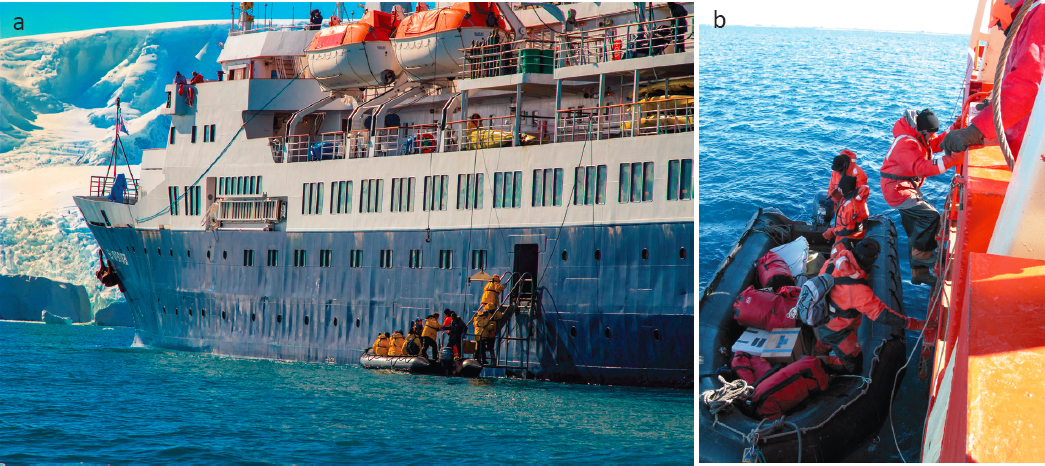

Rigid inflatable boats, zodiacs, and other small boats associated with larger vessels are Critical for studies on global heat and carbon budgets and changing ecosystems (Chapters 4, 5) and Important for studies on sea level rise (Chapter 3; Table 6-1). These small boats are often essential to the deployment and recovery of small AUVs. Access to small boats on the Nathaniel B. Palmer and Laurence M. Gould often requires descending a ladder over the side of the research vessel, which significantly limits the conditions in which small boat operations can be conducted. For example, the design of the Laurence M. Gould makes it difficult to get small boats and equipment safely off the side of the vessel, requiring a rope ladder climb that can be difficult in icy conditions, as well as a well-timed transition from the ladder to the inflatable that can be hazardous in choppy seas (Figure 6-7). Moreover, craning pallets over the side of the Laurence M. Gould into inflatable boats is challenging because of the lack of direct visibility between the crane operator and the boat being loaded with supplies. An improved system for craning equipment into inflatable boats is needed to support the science drivers outlined in this report.

The conceptual design of the ARV includes four high-quality small boats, including a large landing craft and multibeam survey boat (Glosten, 2021). The design currently allows for launching small boats and inflatable craft while at sea. The ability for some of these small boats to be launched in rough seas and to get through thicker, brash ice to land equipment and personnel on Antarctic shores is needed in order to support the science drivers. The ARV will need to be capable of launching and recovering small boats rapidly and safely to take advantage of small windows of good weather, particularly as the need for winter data increases alongside the attendant challenges of operating in difficult weather conditions.

Hull-Mounted Sensors

Hull-mounted sensors (e.g., shipboard sonar and sub-bottom profiler) are Critical for studies on sea level rise, global heat and carbon budgets, and changing ecosystems (Chapters 3–5; Table 6-1). Specifically, these sensors

___________________

13 Presentation to the committee by NSF, May 2023.

14 Presentation to the committee by NSF, May 2023.

15 Presentation to the committee by NSF, May 2023.

SOURCE: (a) Stephen March/Alamy Stock; (b) Burmeister, 2003.

would assist in improving mesopelagic biomass estimates (Chapter 5) and bathymetry, geology, and water mass structures of coastal and deep-sea regions around Antarctica (Chapters 3 and 4).

Acoustic waves are the most effective form of energy propagation in the ocean. Lower-frequency acoustic waves (below about 20 Hz) can propagate thousands of kilometers before their energy is absorbed by the water. The energy of higher-frequency acoustic waves (above 10 or 100 kHz) can attenuate faster, but their short wavelength enables high-resolution observations of ocean environments. These waves can also reflect from interfaces or be scattered by objects and rough surfaces in the water. With advanced signal-processing techniques, the reflected or scattered acoustic wave can be analyzed to image the underwater world. Broadband bioacoustics sonar systems (Lavery et al., 2007; Loranger et al., 2022) are critical instruments for imaging and estimating mesopelagic biomass, and Acoustic Doppler Current Profilers (ADCPs) are necessary for measuring ocean currents in different depths of water (Meijers and Klockers, 2010; Wilson et al., 1997). Wide-angle multibeam echosonar systems (Dorschel et al., 2022; NOAA, n.d.a) and sub-bottom acoustic profilers (Larter et al., 2021) are the most efficient and effective tools for mapping the seafloor and the shallow sub-bottom layering structure (Gales et al., 2014). These mapping tools are especially critical for conducting Antarctic coastal and glacial research in uncharted areas. In addition to seafloor survey, multibeam echosounders also have midwater imaging capabilities and backscattering strength measurements, enabling many other critical observations, including mapping of submerged iceberg or ice shelf fronts/faces, identification and characterization of different habitats for benthic ecosystems, localization and characterization of seeps or hydrothermal systems, and their associated midwater plumes. Besides environmental study, another important application of underwater acoustics is communication and navigation (Freitag et al., 2015; Paull et al., 2014), which is critical for operating UUVs, navigating moorings and profilers, and communicating with underwater instruments and operators.

The preliminary design of the ARV includes a number of science underway sensors, including deep- and shallow-water multibeam mapping, ADCPs from 38–300 kHz, sub-bottom profilers (3.5 kHz, chirp or parametric narrow-beam profiler), marine biology echosounder/sonars from 18 to 200 kHz, an ultrashort baseline transceiver, an acoustic release transponder (12 kHz), hydrophones, and a forward-looking camera and sonar (Antarctic Support Contractor, 2023). It is worth noting that recent development on acoustic and echosounder technology has enabled narrower beams, wider bandwidth, and larger swath coverages for high-resolution surveys and mapping. It is

Critical to include state-of-the-art echosounders to enable the best-possible environmental sensing and underwater communication capabilities.

Towed Sampling and Over-the-Side Instrumentation

Towed sampling and instrumentation (e.g., underway profiling CTD packages, nets for trawling, multichannel streamers and airgun arrays, controlled-source electromagnetics, towed magnetometers) are Critical for studies on global heat and carbon budgets and changing ecosystems (Chapters 4 and 5) and Important for studies on sea level rise (Chapter 3; Table 6-1).

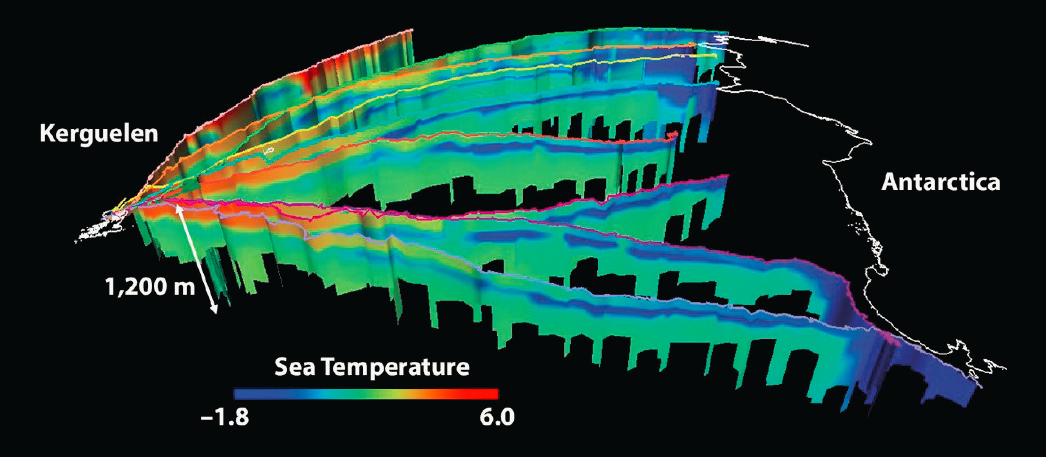

This report identifies the need for interdisciplinary observations that target biogeochemical and ecosystem processes at temporal and spatial scales that reflect the underlying physical dynamics of the region. This need is particularly important for improving constraints in the carbon budget to capture processes related to air–sea exchange, vertical mixing, input of nutrients and micronutrients from glacier melt, and lateral transport and in situ biological processes in coastal zones. The most traditional method for sampling the water column in oceanography is to lower a rosette hosting a range of sensors while the ship is stationary. In coastal Southern Ocean regions, the presence of sea ice and icebergs can limit the availability of open water for deployment of the rosette or can damage sensors attached to it. In situations where the rosette can be deployed, the time between casts may be significant, creating challenges in separating spatial and temporal variability in observed properties.

The need for more frequent and closely spaced CTD casts is particularly acute in coastal regions where the scales of physical circulation tend to be smaller than in the open ocean. Boundary currents along the coast or along troughs in continental shelves may be 1–10 km in width and can vary on subdaily timescales. While autonomous vehicles such as ocean gliders can collect observations with high spatial and temporal resolution, they typically have slow speeds, which can lead to aliasing of rapidly evolving processes. Underway profiling CTD measurements are an essential capability for application, requiring rapid or continuous sampling. Approaches include continuously sampled hull-based water intake to packages or instrument platforms that are towed behind the ship. The latter may sample at uniform depths (e.g., surface arrays or net for capturing biology) or profile vertically through the water column as it is towed (e.g., Triaxus instrument). Towed ship surveys are the best way to collect snapshots of ocean properties and may also be used in combination with remote sensing data products to link surface and interior processes. As analytical technology evolves, making underway observations of both physical and biochemical properties will be possible. The ability to tow new in situ instrumentation needs to be considered, especially those designed for ice-filled seas.

The science drivers identified in this report also support the need for other towed sampling and over-the-side instrumentation, including capabilities for deep-water (greater than 1,000 m) benthic sampling using benthic trawls (e.g., otter trawl, Blake trawl), benthic/epibenthic sleds and baited traps, and midwater pelagic collections with large trawl nets, such as the Isaacs-Kidd Midwater trawl and the rectangular midwater trawl (Chapter 5). Deep trawls will require large drums to hold sufficient wire. In addition, a large back deck with direct access to the aquarium room and wet labs is necessary for biological sampling and experimentation. The deployment of controlled-source electromagnetics (Chapter 3) and active-source seismic reflection and refraction instruments, such as multichannel streamers and airgun arrays (Chapter 3), is also necessary. Multichannel streamers and airgun arrays are currently listed as Science Mission requirements for the ARV (Future USAP, 2022).

Seafloor and Submarine Sampling

Seafloor and submarine samplers (e.g., coring, drilling, dredging, seafloor and borehole observatory) are Critical for studies on sea level rise, global heat and carbon budgets, and changing ecosystems (Chapters 3–5; Table 6-1). Seafloor and submarine sampling would enable better constraints on grounding zone instabilities that may occur during warm paleoenvironments (Chapter 3); changes in ocean circulation, temperatures, productivity, sea ice cover, carbon cycle, and gas exchange (Chapter 4); and sedimentation rates, paleobiology, or active geomicrobiology in Antarctic fjords and ecosystems (Chapter 5).

Specific tools needed for seafloor sampling include long (40–50 m recovery) piston coring, which requires a substantial side A-frame and appropriate winch and wire capabilities for heavy lifts. Other needs include

(1) seafloor lander drills that enable roughly 200 m subseafloor recovery, which require a robust stern A-frame capability of at least 30 metric tons for operation to 2,500 m depth (or 40 metric tons for operation to 4,000 m depth), and (2) sufficient ship deck space for specialized launch and recovery systems, conducting cable umbilicus with a portable winch, and van- or laboratory-based support. Various shorter sediment coring devices include gravity and multicoring systems and towed seafloor dredges that can sample volcanic and other rock outcrops, as well as undisturbed collections of sediment–water interfaces. Dynamic positioning is also a critical vessel capability for seafloor sampling, as is a mechanism to protect over-the-side equipment and its wires from chafing damage due to heavy sea ice. Camera systems mounted on sampling devices, ideally with real-time imagery or video feed for detailed site selection, are desirable for some applications in which conducting cable can be used.

The preliminary design of the ARV currently supports 40–50 m piston coring, and a stern A-frame with 9 m (30 ft) of vertical clearance and strength members up to 120,000 lbs (54 metric tons) break strength (Antarctic Support Contractor, 2023). If the larger seafloor sampling equipment that requires specialized staffing and support will see intermittent use on the ARV, it would be desirable to share this equipment with other vessels, such as the equipment within the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS) fleet, with common management for cost-effective, global use.

At present, long sediment coring facilities exist on some potential partner vessels (e.g., the Kronprinz Haakon and the Araon). Academic lander-based drilling with penetration over 100 m currently exists in the MeBo facility at the University of Bremen in Germany16 and is utilized on several German ships, including the icebreaker Polarstern, as well as others in the global oceans. A similar seafloor drill was recently acquired by the Geological Survey of China. Some additional lander drilling systems are in use by the offshore geotechnical industry in several countries. A ship-mounted drilling system, Shaldrill, was used in the past on the Nathaniel B. Palmer via a small moonpool on the fantail (Scientific Drilling, 2006). Lack of a similar moonpool on the ARV would likely limit seafloor drilling options to those that can be deployed over the side.

At the time of this report’s publication, NSF has decided to not renew its cooperative agreement with Texas A&M University for operations of its flagship JOIDES Resolution drilling vessel (NSF, 2023a). This could eliminate, for a time, the ability for a U.S. vessel to obtain deep drill cores around Antarctica. NSF notes the possibility of a future drillship, but some gaps in capabilities are likely to occur, underscoring the need for long-coring and lander drilling that could be deployed from the ARV. The availability of these facilities on the ARV would open new areas for study that were inaccessible from JOIDES Resolution, which is not an icebreaker.

Live Organism Experiment Capabilities

It is Critical for studies on changing ecosystems (Chapter 5; Table 6-1) that vessels be capable of accommodating experiments with live organisms. This includes modular aquarium facilities large enough to accommodate a range of tank sizes and configurations and plumbed with running seawater. Some research will also require an optional workbench in the aquarium space. The facilities require controlled seawater systems (including control of temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen) and should provide sufficient space for specialized equipment (e.g., respirometry chambers). For experiments on organisms occupying the mesopelagic or benthic environments, where ambient seawater temperature is warmer than at the surface, seawater supplied to the aquarium room or on-deck incubators can be warmed to mimic deeper ambient temperatures. In addition, the ability to chill incoming seawater would allow researchers to continue live experiments while the ARV transits north and could be useful in the future if researchers propose to transport live animals outside of the Antarctic, as has been done by the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and Australian Antarctic Division. If the aquarium facilities on the ARV are located immediately adjacent to the back deck, live organisms can be quickly and efficiently transported from the deck to the aquarium. In addition, many live experiments are conducted in incubators, either outdoors on deck or inside in laboratories dedicated to live organism work. Outdoor incubation experiments require adequate deck space and running seawater. Indoor incubation experiments require incubators with adjustable internal temperatures and clean laboratory space that is free from prior use of fixatives (e.g., formaldehyde).

___________________

16 Personal communication by Tim Freudenthal, March 2023.

The preliminary design of the ARV indicates that many of these requirements have already been considered. For instance, the Aquarium Room has direct access to the Starboard Working Deck and will support large and small free-flowing aquaria. The Science Seawater System will include two scientific seawater pumps and two incubator seawater pumps, which will provide ambient-temperature seawater to science laboratories, laboratory vans, deck incubators, and the Aquarium Room. However, additional requirements outlined above should also be considered, including the ability to bring ambient seawater temperature up to that of warmer, deeper water masses for experiments mimicking temperatures at depth. In addition, systems that will allow for the precise control and manipulation of dissolved oxygen, temperature, and pH should be considered and the space should be designed to accommodate such systems.

Low-Temperature Storage

Low-temperature storage is classified as Critical for studies on changing ecosystems (Chapter 5) and Important for studies on global heat and carbon budgets (Chapter 4; Table 6-1). Appropriate temperature storage is needed for certain sensitive experiments, including advanced molecular analyses and redox-sensitive chemical measurements. Storage requirements needed for biogeochemical studies require a range of temperatures (+4℃, –20℃, and –80℃), which are standard on research vessels and included in the current ARV design (Antarctic Support Contractor, 2023). Advanced molecular analysis often requires immediate ultralow freezing with liquid nitrogen, –80℃ capacity, and a walk-in freezer is useful for sea ice–core processing and storage. In addition, because some projects may require additional but temporary low-temperature storage or incubation, low-temperature incubators, refrigerators, and freezer capabilities should be included to allow for flexibility in storage capacity.

Berthing

Having more than 45 berths for science and support staff is classified as Important for studies global heat and carbon budgets (Chapter 4; Table 6-1). While berthing requirements similar to the NathanielB. Palmer (39–45 berths) are Critical on an icebreaker to support all of the science drivers, the committee did not find that a significantly larger number of berths was justified if they were at the potential expense of other Critical/Important capabilities, such as full helicopter support.

Large numbers of berths would improve the ability to carry out large and technically complex projects17 that require numerous specialty technicians and science teams that span multiple disciplines but are focused on a singular science question. This approach has proven successful in the Southern Ocean recently, in that the ARTEMIS (Autonomous RemoTe Environment Monitoring System) project deployed multiple autonomous vehicles so that real-time interpretation of the physical circulation informed target areas for focused chemical and biological sampling. These focused observations are needed for building process-based understanding, as well as validating coupled climate models. Berthing requirements are also important to accommodate various current and future technologies, such as large UASs, ROVs, and AUVs. For example, specialized large ROVs and AUVs such as the National Deep Submergence Facility’s Jason and Sentry, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Nereid Under Ice hybrid vehicle typically have operations support teams of 5–10 personnel. Large UASs such as future geophysical survey systems might require many berths for certified flight-support personnel and instrument technicians. In the near term, an increased use of these technologies will likely require a greater number of berths for science and technical support than have been needed for similar science projects in the past.

Currently, the Nathaniel B. Palmer has capacity for 39–45 science and technical personnel, and the Laurence M. Gould has capacity for 26 science and technical personnel. Following several prior community reports that called for 45–55 berths (Chapter 2), the ARV is designed for about 55 science and technical personnel

___________________

17 Some historical large and technically complex projects include the Global Ocean Ecosystems Dynamics (GLOBEC) project, the U.S. Joint Global Ocean Flux Study (JGOFS), the Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC), the Research on Ocean-Atmosphere Variability and Ecosystem Response in the Ross Sea project (ROAVERRS), and the Export Processes in the Ocean from Remote Sensing (EXPORTS) field campaign by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

(Glosten, 2021). While the greater berthing ability of the ARV will allow multiple science projects per cruise, additional berths may lead to difficulties in scheduling unless the science teams have compatible goals and are well coordinated. Harmonizing multiple science projects per cruise can be facilitated by significant precruise planning and information exchange across the different teams (including the PIs of each project), who should meet to discuss how their respective goals can be achieved within the cruise’s time constraints. More science projects per cruise will likely result in longer cruises, which may result in science teams spending many days at sea with only a few days of dedicated ship time for their respective projects. Some investigators may not participate in prolonged cruises because of teaching or administrative responsibilities associated with their respective academic appointments.

The designed berthing ability of the ARV is consistent with the capacity of science and technical personnel on many partner vessels. The berthing capacity of other nations’ Antarctic and polar research vessels ranges from about 117 passengers and 32 crew on the Australian research supply vessel Nuyina, to the Norwegian research vessel Kronprins Haakon, which can support about 40 scientists and technical personnel and about 15 crew. Other vessels’ berthing capacities include about 100 passengers/researchers and about 45 crew aboard the South African research and supply vessel Agulhas II; about 90 crew and scientists aboard the Chinese polar research vessel Xue Long 2; about 60 scientists, researchers, and support staff capacity on the British research ship Sir David Attenborough and Korean research vessel Araon; about 53 scientists onboard the German research vessel Polarstern; and 44 scientists aboard the Swedish icebreaker Oden (Appendix B).

TOOLS AND TECHNOLOGY

To adequately address the suite of science drivers outlined in this report, platforms that can extend the spatial and temporal reach of traditional vessel-based observations and capabilities are necessary. They also provide observations in areas and locations where vessel access will not be available (either because of limited capabilities or scheduling). Over the longer term, advances in many of these tools and technologies will provide cost-effective observational access beyond the reach of what can be supported solely through a single icebreaker.

To assist NSF in the consideration of trade-offs between capabilities given budgetary constraints for investments in tools and technologies, the committee classified them as Critical or Important for advancing the report’s three science priorities (Table 6-2). Justification for these classifications are expanded in the sections below, including references back to the science priorities in Chapters 3, 4, and 5.

Uncrewed Aerial Systems

UASs (drones) are Critical for studies on global heat and carbon budgets and changing ecosystems (Chapters 4 and 5) and Important for studies on sea level rise (Chapter 3; Table 6-2). Specifically, the use of UASs would enable population-trend monitoring of key species for which there is limited knowledge (Chapter 5). UAS capabilities are also rapidly replacing crewed aircraft for remote sea ice surveys, surveillance for ice navigation, and air–sea interactions (Chapters 3 and 4). Additionally, UASs are an emerging capability for buoy and float deployment for observations of changing ocean circulation and sea ice, and ice–ocean interaction processes (Chapter 4). For example, inexpensive air-drop systems are currently available for light-duty UASs that could be used to deploy, for example, expendable ocean profilers or small drifters. For larger payloads (e.g., Argo floats), systems such as the Bell Autonomous Pod Transport UASs can deliver a 70-pound payload at ranges of tens of miles (Bellflight, 2023) in a platform compact enough to be operated from a ship. To fully realize this potential, new buoy and sensor platform capabilities will need to be developed for uncrewed deployment in or on sea ice. Very long–range UASs have the potential to support large-scale electromagnetic surveys of ice thickness and other aerogeophysical remote sensing (e.g., ice-penetrating radar, gravity, magnetics, laser altimetry) that are presently possible or practical only with fixed-wing aircraft from coastal stations. Similarly, future developments in long-range, heavy-lift UASs and sensor platforms may permit the deployment of an array of miniaturized platforms (including ice buoys and profiling floats) that can, in some cases, provide alternatives to both icebreaker and helicopter support.

TABLE 6-2 Matrix of Critical (C) and Important (I) Tools and Technologies for the Three Science Drivers Identified in the Report

| Sea Level Rise | Global Heat and Carbon Budgets | Changing Ecosystems | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncrewed aerial systems | I | C | C |

| Uncrewed underwater vehicles | C | C | C |

| Autonomous surface vessels (capable of operating in high-latitude open ocean) | I | C | I |

| Ocean moorings | C | C | C |

| Ice shelf–tethered moorings and profilers | C | I | I |

| Buoys, sea ice–tethered platforms, and profiling floats | I | C | I |

| Cabled observationsa | C | C | I |

| Small coastal vessel | I | C | |

| Remote sensing observations | C | C | C |

| Fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters | C | I | I |

| Drilling and coring | C | I | I |

| Instrumented animals | C | C | |

| Autonomous land-based and ocean-bottom stations | C | ||

| Seawater aquarium facilities at Palmer and McMurdo stations | C | ||

| Access to sea ice and ocean from McMurdo Station | C |

a Emphasis on technology development and evaluation.

NOTE: The most crucial capabilities are Critical, with Important and blank cells indicating lesser importance.

Current and future UASs operated from the ARV or shore stations can greatly extend science observational capabilities of either the vessel or what is feasible immediately from shore. In addition, they can provide sea ice data crucial for planning the ship’s track and for sea ice travel. However, UASs capable of providing the necessary range to provide these data are beyond the ability of most PIs to support. A fleet of UASs and licensed pilots supported by the Office of Polar Programs for these purposes would benefit logistical planning of ship tracks and sea ice travel. Finally, if the ARV does not have full helicopter support, it would be beneficial for the ARV to have its own fleet of both small and heavy-lift UASs with certified pilots to supplement ship-based operations.

As sensor capacity and range capability evolve, station-based operation of UASs will extend many observational capabilities traditionally done from crewed aircraft or from icebreakers to shore-based operations (e.g., for aerogeophysical surveys over sea and land ice, deployment of floats near the coast, or for population surveys). This will require future consideration of what infrastructure and support for large, long-range UASs will be needed at McMurdo and Palmer stations.

Uncrewed Underwater and Autonomous Surface Vehicles18

UUVs, including ROVs, AUVs, and gliders, are Critical for studies on sea level rise, global heat and carbon budgets, and changing ecosystems (Chapters 3–5; Table 6-2). In contrast, ASVs are Critical for studies on global heat and carbon budgets and Important for studies on sea level rise and changing ecosystems (Table 6-2). AUVs and ROVs will enable the study of heat transport in sub–ice shelf cavities (Chapters 3 and 4), air–sea exchange of heat and carbon dioxide (CO2) (Chapter 4), and biogeochemical observations of continental fluxes (Chapter 5).

___________________

Gliders and ASVs will support spatial observations of rapid ocean processes (e.g., mesoscale circulation or ice-edge process studies; Chapter 4).

These vehicles are rapidly evolving technologies that promise to supplement, and in some cases supplant, in situ, stationary, or drifting platform observations. However, UUV capabilities will not be able to replace most vessel-supported observations or sampling, particularly for remote locations. Rather, they represent an enhancement to a vessel’s observational capability that can enable increased spatial and temporal reach and improved observations in previously difficult-to-access areas, such as at the ice shelf front, under ice shelves, or under thick sea ice. Glider operations under sea ice for days to weeks have been demonstrated in the Arctic (Lee et al., 2022), but at present, only a few glider operations under ice have been conducted in the Antarctic. For example, gliders have made sustained, year-round observations under the Dotson Ice Shelf with acoustic navigation aids (Rainville et al., 2019). Under–ice shelf observations have also been achieved with the U.K. National Oceanography Center Autosub and the Swedish Hugin AUVs. These types of vehicles are expensive, complicated, have relatively short sampling durations, and they require dedicated technicians. Improved capabilities for long-term autonomous observations at ice shelf front (Friedrichs et al., 2022; Miles et al., 2016b) and under ice shelves (e.g., Rainville et al., 2019) are emerging, but even long-range vehicles will still require ship-based access for deployment.

Sustained AUV observations under ice in remote areas will require new long-range and long-endurance vehicles with sophisticated navigation and environment-aware mission planning. Existing technology could achieve these requirements via an acoustic localization network similar to the HAFOS network19 that was previously maintained in the Weddell Sea for under-ice floats (Boebel et al., 2005). Sustained navigation under ice over very long ranges (several thousand kilometers) are also possible with advances in terrain-aided and environment-aware navigation, and with advances in hybrid vehicles (e.g., combining efficiencies of buoyancy- and thruster-driven operation), low-power sensors, and high-capacity battery technology. These advances may enable limited ice–ocean observations over very long ranges from shore, potentially alleviating the need for icebreaker support for deployment, recovery, or both. Improvements in reducing size, cost, and power requirements of navigation aids and power-recharging networks for AUVs may facilitate more widespread and sustained observations under ice in the decades to come.

ASVs hold promise for sustained observations in ice-free Antarctic waters. Saildrones and Wave Gliders can provide autonomous observations of air–sea fluxes but have seen limited use and will face limitations in the challenging conditions of the Southern Ocean. Emerging ASV designs (e.g., the 15 m Mayflower Autonomous Ship) may have capabilities and payload capacities that far exceed those of previous ASVs and may supplant some measurements and sampling that are currently supported by crewed vessels in open-water regions. However, these are likely to be limited to monitoring-type activities and unlikely to supplant crewed vessels for process or most biological studies for the foreseeable future.

Some international partners have facilities that support large UUVs for use by individual investigators (such as the U.K. Autosub), but the United States does not have a similar facility. The National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF), which is overseen by UNOLS, does host ROVs for this purpose, but the current NDSF fleet is not typically used in the Antarctic. However, large, specialized, state-of-the-art, under-ice ROVs have been developed and are available in the United States (Bowen et al., 2014), and smaller UUVs (gliders, AUVs, ROVs) and ASVs are becoming widely available in the United States and elsewhere. Expansion of shared instrument and equipment pools to support cost-effective and equitable access to large ROVs and AUVs with under-ice capabilities would require significant investment. However, it would also require significant investment from NSF to support individual researchers purchasing these platforms. One approach might be for the USAP to partner with other Antarctic programs through the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) or the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP) to develop, maintain, and position a shared pool of resources at vessel homeports. If investments in pooled resources are considered, it is important to weigh how emerging technologies might supersede existing capabilities as autonomous vehicle capabilities are rapidly evolving.

___________________

19 The HAFOS, or the hybrid Antarctic float observation system, is a mooring network in the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean.

Ocean-Bottom Moorings and Ice Shelf–Tethered Moorings and Profilers20

Ocean-bottom moorings (e.g., profiling moorings, novel seafloor borehole monitoring systems, upward-looking sonars) are classified as Critical for studies on rising sea level, global heat and carbon budgets, and changing ecosystems (Chapters 3–5; Table 6-2), whereas ice shelf–tethered moorings and profilers are classified as Critical for sea level rise studies (Chapter 3; Table 6-2). Specifically, moorings and ice-tethered profilers enable studies of buttressing floating ice (Chapter 3), and sustained ocean observations by profiling moorings would help elucidate changing emissions and the Southern Ocean’s uptake of CO2 (Chapter 4). Additionally, innovative moorings could be delivered to under-ice cavities by ROVs and provide an alternative means of sustained, targeted measurements under ice shelves, where access via the surface is logistically challenging (Chapter 3). Finally, moorings and borehole systems like CORKs21 may help estimate the distribution, volume, and composition of groundwater discharge and biogeochemistry (Chapter 5).

Sound sources on moorings can enable UUV acoustic navigation. The permanent ensonification of one or more ice shelf cavities would offer a natural laboratory to develop and utilize autonomous platforms for studying ocean–ice interactions. The investment in deploying and maintaining an array of acoustic moorings for a single research project or research team may not be feasible, but a long-term investment in this acoustic technology, potentially in collaboration with other National Antarctic Programs, may speed technology development as well as scientific advances across projects supported by a range of funding bodies.

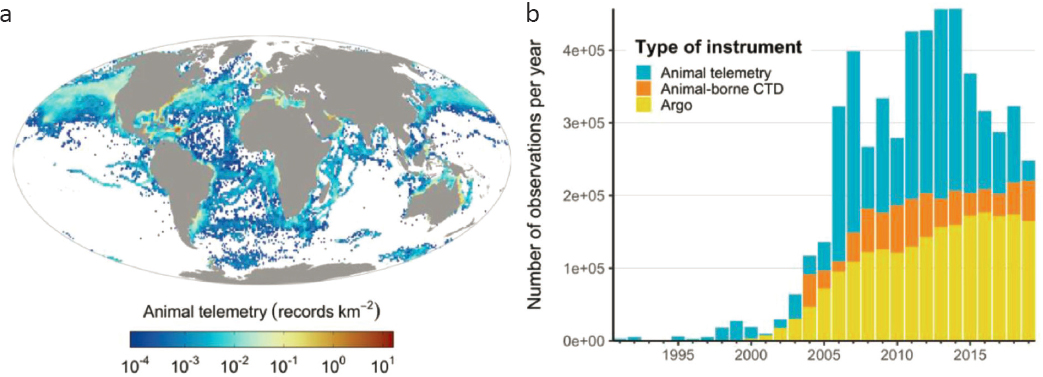

Buoys, Sea Ice–Tethered Platforms, and Profiling Floats

The use of buoys, sea ice–tethered platforms, and profiling floats are Critical components of studies on global heat and carbon budgets (Chapter 4) and Important components of studies on sea level rise and changing ecosystems (Chapters 3 and 5; Table 6-2). More specifically, profiling floats, ice-tethered profilers, and ice-deployed drifting platforms (ice mass balance buoys, air–sea flux buoys, and meteorological platforms, as well as other surface-based drifters) are an essential and expanding capability for observations of ocean properties; sea ice growth, decay, and drift; and air–sea interactions. Perhaps most significant of these for the Southern Ocean is the BGC-Argo float program, which has provided the majority of the off-shelf ocean salinity and temperature profiles in the Southern Ocean in winter, and SOCCOM22 floats, which also provide critical information on gas exchange. BGC-Argo floats have provided some of the only in situ observations of winter ocean processes, such as the return of the Weddell Sea polynya (Campbell et al., 2019; Turner et al., 2020).

Widespread ocean property measurements described in Chapter 4 will require expanded use of ice-capable and shelf-sea BGC-Argo floats, which are sparsely deployed in the Southern Ocean at present. Localizing floats under ice remains a significant challenge in the Southern Ocean. As with UUVs, an under-ice BGC-Argo network would benefit from a moored acoustic transponder network, which would require significant vessel support to maintain. Potential innovations could employ emerging multihop communications for simultaneous localization of multiple floats, or novel technologies for low-cost, low-power acoustic communications.

Ice-tethered profilers have seen limited use in the Antarctic, in part because of their short lifetime relative to the Arctic due to differences in ice drift. They are, however, viable and useful for fast ice deployments, particularly in the vicinity of ice shelves. However, emerging lower-cost platforms (e.g., those that use inexpensive sensors or that are limited to shallow depths [e.g., Lee et al., 2016]) can provide similar measurements on a platform better suited for the Antarctic.

The greatest challenge to widespread spatial and temporal distribution of floats in the Antarctic (particularly in shelf seas) is the small number of ship-based deployment opportunities. Innovations in float and buoy platforms that can be deployed by air (e.g., Jayne and Bogue, 2017)—potentially by drone—and ice-tethered buoys that can survive freeze-in will enable expansion of autonomous drifter observations.

___________________

21 CORKs (Circulation Obviation Retrofit Kits) are instruments that are long-term observatories to investigate subseafloor fluid circulation. These are often linked to a long-term data logger on the seafloor, accessible with a human-occupied or remotely operated vehicle (WHOI, 2000).

22 SOCCOM is the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling project.

Cabled Observations

The use of cabled observation arrays are Critical components of future work on sea level rise and global heat and carbon budgets (Chapters 3 and 4; Table 6-2). Cabled observations are also classified as Important for acoustic observations on changing ecosystems (Chapter 5; Table 6-2). The use of fiber optic cables as long-term monitoring platforms has gained attention in recent years. In particular, NSF supported a workshop in 2021 to explore the value of a submarine fiber optic telecommunications cable from New Zealand to McMurdo Station, with terabit-scale networking capability. Direct fiber connectivity to McMurdo Station may also enable improved connectivity to Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station and the science infrastructure at both stations. The primary motivation for this cable is to eliminate current bandwidth constraints and to reduce latency of existing satellite-based communication. However, it has also been proposed that the cable infrastructure could act as a scientific platform (Scientific Monitoring and Reliable Telecommunications [SMART] cable) with the capability to monitor ocean conditions (e.g., temperature, current speed, seismic activity). In addition to laying this cable along the seafloor, parts of the cable could be designed to be buoyant so that it is oriented vertically and could provide information on the vertical structure of key ocean properties.