Critical Issues in Transportation for 2024 and Beyond (2024)

Chapter: Workforce

All funding possibilities have advantages and disadvantages, particularly the equity consequences of direct user charges. Even so, reliance on publicly imposed user fees has sustained investments in essential transportation infrastructure for decades and revenues from tolls and other charges imposed on highway users can be, and are being, used to fund transit and help offset welfare losses to low-income groups. Policy-maker reluctance to increase traditional user fees have resulted in their erosion, leading to even greater reliance on general fund revenues and their associated uncertainties. Increased evaluations of real-world experience with new and existing user fee–based options and public versus private infrastructure ownership and funding will be invaluable to policy makers at all levels as they debate how to pay for the nation’s transportation network.

Adequate investment in transportation infrastructure by the public and private sectors is essential for ongoing and future prosperity and a thriving society. Finding revenue sources to supplement or replace the roughly $100 billion annually from motor fuels taxes is particularly important as an increasing share of motor vehicles shift to electric drive. However, the mechanisms for raising revenues have important influences on the demand for travel, system performance, and total investment requirements. Revenues gained from tolls and other user fees constrain demand induced by increased capacity, improve traffic flow, and thereby reduce the need to increase capacity, but they can also be inequitable for those with low incomes. Questions about the share of investment for passenger and freight infrastructure that should rely on federal rather than state and local government support, be user fee–based and derived from tolls, or be privately owned and funded through user fees have long been contentious. Ongoing experimentation with alternative funding and financing approaches and user fees will be invaluable to policy makers and officials as they manage the nation’s $6.6 trillion investment in fixed capital assets.

![]() Foundational Factors and Policy Levers

Foundational Factors and Policy Levers

Workforce

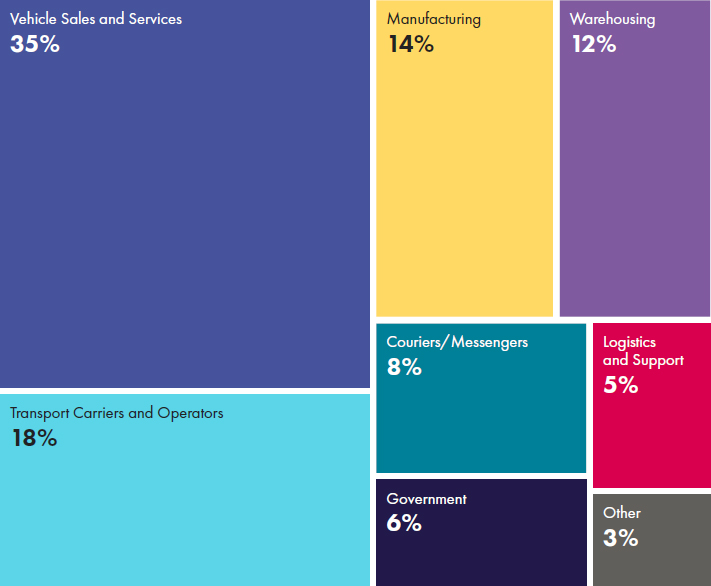

Transportation systems in advanced economies depend on a wide range of people with diverse expertise and perspectives. The 14.3 million transportation and transportation-related industry employees in the United States represent 10.2 percent of the entire U.S. workforce, a share that has remained steady since 2000.185 Transportation employees work in diverse fields (see Figure 18). Most jobs (34 percent) are in vehicle sales, parts, repairs, gas stations, and related sectors. The relatively high proportion of blue-collar jobs in transportation results in average wages and benefits

NOTES: The category of transport carriers and operators includes all firms moving freight and passengers. Total may not add to 100 percent due to rounding.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics. National Transportation Statistics Table 3-23.

that have ranged from 15 to 20 percent less than the average for all occupations since 2005.186

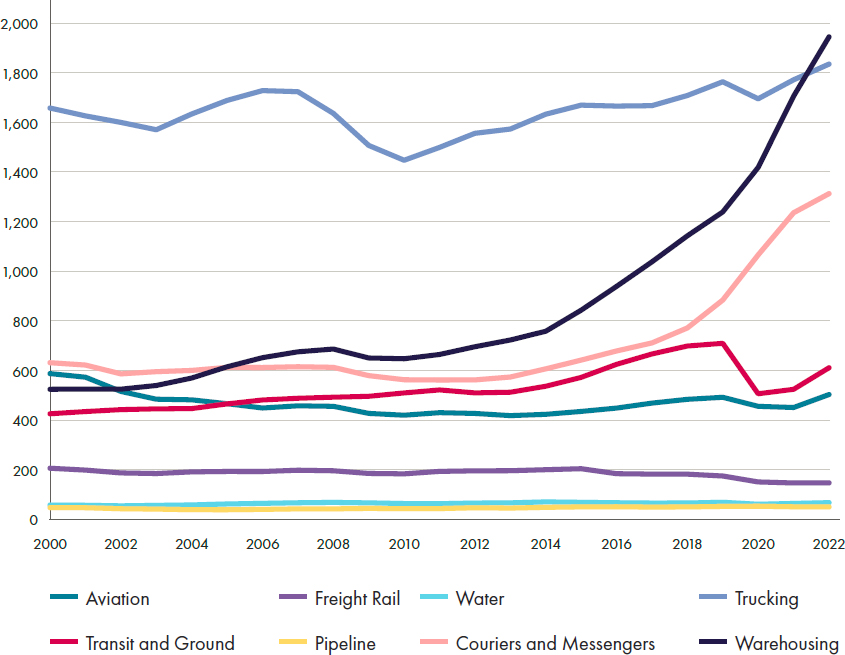

Notable trends in employment include the relatively large and fast-growing shares of jobs in warehousing and couriers and messengers (see Figure 18). Together, these categories account for 18 percent of all transportation jobs, and both groups have grown sharply since 2010 (see Figure 19). An increasing reliance on e-commerce explains much of the growth in warehousing jobs and the proliferation of warehouses in urban peripheries.187 The same may be partly true for employment growth for couriers and messengers as well.

The last 20 years have seen steady employment growth in trucking during the long economic recovery from the “Great Recession” that began in

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Hours Worked and Employment Measures, Detailed Industries: Hours and Employment. https://www.bls.gov/productivity/tables/home.htm.

2008. By contrast, employment in aviation and railroads has steadily declined over the same period, even as their output increased. This may help explain labor productivity gains in aviation and rail, described in the Economy section, as well as increased labor unrest over wages and working conditions for modes that have to operate 24/7/365.

Labor issues in the motor vehicle sales and service, as well as manufacturing, sectors are similar to those of the rest of the economy. However, as part of the efforts needed to shift to renewable energy sources and adopt EVs, overall employment in motor vehicle manufacturing and fossil fuel production for transportation may fall even as other manufacturing and blue-collar jobs associated with the energy transition expand.188 Labor strikes in automobile manufacturing at the time of this writing in October 2023 reflect worker concerns about lower compensation in EV and battery factories.189

Nearly all sectors have slowly rebounded from declines in labor force participation during the COVID-19 pandemic.190 Among modal operators,

companies struggled to rebuild truck driver, pilot, and railroad workforces after layoffs in 2020 and 2021. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, challenges in recruiting and retaining long-distance truck drivers appear to reflect working conditions and compensation levels that many workers find unappealing.191 Shortages of air traffic controllers, which became acute in early 2023, result from the curtailment of training during the pandemic and the long-standing difficulties in attracting and retaining skilled controllers to live in high-cost areas, such as within a reasonable commuting distance of FAA’s New York facility, which is also responsible for managing the nation’s most challenging airspace.192

The resurgence of freight and passenger travel demand has also led to labor unrest in railroads and aviation. Congress intervened in late 2022 to avoid a nationwide strike of railroad workers.193 The forced settlement raised average wages by 24 percent over 5 years but did not address workers’ concerns about inadequate sick leave, although major railroads and unions subsequently negotiated to address these concerns. Airlines report that they are unable to operate as many flights as passengers demand because of a pilot shortage.194 At the same time, pilot unions argue that entry-level pay and working conditions are unattractive to the thousands of trained and certified pilots who are not actively employed as such.195

As noted in the Economy section above, the deregulation of the trucking industry increased productivity but at a high cost to workers. Aviation and railroad workers remain largely unionized, but not intercity trucking. Drivers in the intercity general freight and truckload sectors of the industry (more than 50 percent of truck drivers) experienced substantial cuts in worker income following deregulation. Truckload drivers (about 20 percent of drivers) now also work very long hours (up to and beyond the 60-hour-per-week limit on driving set in regulation).196 Long days (up to 11 hours driving within a total of 14 hours on duty) and company pressures to meet pickup and delivery schedules lead to driving while fatigued or exceeding speed limits to meet schedules within the 11-hour limit.197,198,199

As described in the Economy and Safety sections of this publication, the slow transition to higher levels of automation may significantly improve freight productivity and reduce the demands on human operators that lead to errors, but automation may significantly reduce employment in freight as well. Trucking alone employs about 3.5 million drivers, making it one of the largest occupations and a major source of blue-collar jobs.200 In the near term, as in any labor market, wages and working conditions are issues that management and labor must come to terms on, and it is critical that they do so. Safe and efficient operations in transportation firms that operate on a 24/7/365 schedule depend on having engaged, committed workforces. As total manufacturing and related jobs in parts and supplies decline and freight transportation slowly