The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Applications and Lessons Learned

3

Applications and Lessons Learned

Highlights from the Presentations of Individual Speakersa

- Wearables allow for “passive” detection of eating events but by themselves may not provide insights of the foods being consumed. (Sazonov)

- AI and ML methods form the backbone of technology-based dietary and behavioral assessment, but many technical issues have yet to be resolved, and ethical and privacy issues need to be addressed. (Sazonov)

- The microbiome and diet are intimately linked. (Knight)

- ML/AI methods are critical for microbiome analysis, and many of the principles likely apply to other multivariate datasets, such as for food. (Knight)

- Ethical considerations with microbiome interventions, especially around bias, stratification, and safety, also likely apply to dietary intervention. (Knight)

- Addressing metabolic issues that were once rare but are more prevalent today may be possible through a better understanding of how nutrition affects the microbiome and today’s common chronic diseases. (Knight)

- Exposome research is key to informing precision nutrition by providing an understanding about how exposures and pertur-

- bations in endogenous metabolism are linked to an individual’s genetics and states of health and wellness. (McRitchie)

- When developing dietary signatures using either untargeted or targeted metabolomics without carefully controlling the diet, the signature may not be accurate. (Lamarche)

- AI has great potential for the nutrition field, but significant challenges must be addressed, such as appropriately considering the quality of the data, developing a common language between nutrition and computational science, and standardizing methods and approaches. (Lamarche)

- Human studies will always have missing data, which can lead to biased and misleading results. (Das)

- Public funding of ethical technologies to benefit society is imperative, particularly when solving problems arising from negative externalities and supercharging positive externalities. (Smith)

- The main barriers to adoption of AI in agriculture are not related to issues of trust but whether AI will solve real-life problems. (Smith)

- A priority should be to invest in problems beset by externalities and develop technologies in those contexts that can help surmount the challenges of human behavior, a much better path than trying to figure out ways to manipulate human behavior. (Smith)

- A lack of data can make it challenging to support historically disadvantaged and underserved farmers and ranchers without exacerbating existing challenges. (Jablonski)

- It is important to show the intended beneficiaries of a model the evidence used to power it and generate ideas that can improve the end user’s situation. (Jablonski)

- Develop tutorials written in accessible language that identify limitations of the different methods, how to properly use a method, and how big a sample is necessary. (McRitchie)

- Addressing the scope of AI and ML projects requires a multidisciplinary approach that involves all of the research areas and creates a transdisciplinary approach requiring awareness and the resources to support it. (Das)

- Accessing data from private entities, including farmers and consumers, continues to be a challenge because of issues of ownership and who will profit from the information. (Smith)

- The key to getting entities to share their data is to show them the benefits for them of doing so and create a safe haven for data sharing. (Dugundji)

__________________

a This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

WEARABLES: SENSORS, IMAGES, AND AI FOR FOOD INTAKE MONITORING

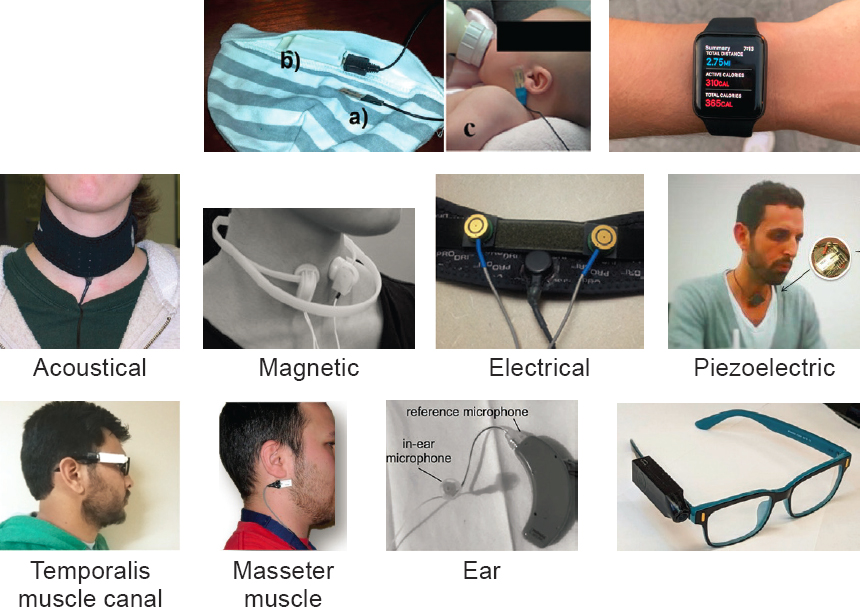

Edward Sazonov, the James R. Cudworth Endowed Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and head of the Computer Laboratory of Ambient and Wearable Systems at the University of Alabama, said that the first and simplest task to perform with a wearable device (see Figure 3-1) is to detect when and perhaps how much someone is eating. For infants, for example, monitoring sucking or swallowing would be effective (Farooq et al., 2015). Detecting hand gestures or chewing would be easy in a slightly older child.

For older children and adults, hand-to-mouth monitors could provide information about eating (Dong et al., 2012), but they would have relatively low accuracy because of the similarity to everyday gestures and provide no insights into the type of food consumed, said Sazonov. Swallowing monitors worn around an individual’s neck would provide a reliable way to detect food and beverage consumption, but people do not like wearing such devices, and they also do not identify food type (Farooq et al., 2014; Kalantarian et al., 2015; Kandori et al., 2012; Makeyev et al., 2012). Chewing monitors are reliable for detecting food and beverage consumption, although sipping beverages may generate false negatives and chewing gum or lip biting may generate false positives, and they would not provide information about food type (Farooq and Sazonov, 2017; Hossain et al., 2023; Päßler et al., 2012; Sazonov and Fontana, 2012).

Sazonov explained that machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) models should employ supervised learning given the importance of providing labels for when a person is eating or not and the type of food they are eating. Data collection, cleaning and labeling the data, feature extractions, and model training and validation are critical steps. The limitation of using ML/AI with wearable devices is that only simple, small models can be deployed. Sophisticated and computationally intensive models require the

SOURCE: Adapted from materials presented by Edward Sazonov on October 10, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Farooq et al., 2014, 2015; Kalantarian et al., 2015; Kandoori et al., 2012; Makeyev et al., 2012.

edge or the cloud, so the device must have network connectivity (Sabry et al., 2022). The beauty of wearable devices is they can provide information via passive detection so participants do not have to report eating events. Wearables can measure the timing and duration of eating, evaluate daily eating patterns, and evaluate the microstructure of eating—the number of bouts, hand gesture rate, chewing rate, and speed, for example (Doulah et al., 2017).

Another capability of wearables, said Sazonov, is estimating the amount of food consumed by connecting the number of hand gestures, bites, chews, and swallows to both the mass and energy content of the food (Dong et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2019). Some wearables, he noted, can take pictures of what the wearer is eating (Liu et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2014). A device his group has developed attaches to an eyeglass temple and captures images of the wearer’s food, reveals the eating progression, and automatically detects eating, capturing images of food intake (Doulah et al., 2021). When an ML algorithm running on the device decides that a person is eating, it takes a picture of the food. A nutritionist or image recognition system then analyzes the images to identify the type of food and portion size, although the error rate for both can be large (Doulah et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2009). Sazonov said that an ML algorithm for image-based food classification can be more accurate and provide additional insights (Lo et al., 2020).

Food detection, explained Sazonov, can be achieved by classifying images as food and nonfood, identifying instances of food objects in an image, and identifying the type of food (Chen et al., 2021). A deep learning (DL) algorithm can transform images into text descriptions and provide a synopsis (Qiu et al., 2023). AI can also transform a food image into a recipe that would identify its ingredients (Marin et al., 2021). Sazonov said that segmenting food images is challenging but important for estimating the portion size for each individual food item (He et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2021b), perhaps the most difficult problem for image analysis (Bathgate et al., 2017). A common approach is to have a participant place a fiducial marker in the image for size reference. Images of leftovers provide estimates of the amount consumed. Another approach is to use monocular vision; with the distance from the camera to the food, it can provide an estimate of portion size.

Natural food behavior, said Sazonov, is significantly more complex than commonly used staged food scenes. Food items, for example, can be occluded or consumed in the same bite with other foods. People consume food in many environments and may eat from shared plates. A dimensional reference is not always available, either. Compliance with wearing a device can be a problem, and eating out of protocol is common. It is possible to assess protocol compliance from image and sensor data, he added (Ghosh et al., 2021).

Using images raises privacy concerns, and images may contain information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability

Act. Sazonov noted that privacy issues are not limited to personal cameras, given the one surveillance camera for every 6.5 people in the United States. Recommendations exist for using wearable cameras in health behavior research (Kelly et al., 2013), as do privacy-preserving techniques for image analysis (Hassan and Sazonov, 2020). Imaging also has inherent limitations, particularly regarding similar-looking items having different nutritional value, such as a gallon of whole versus nonfat milk.

MICROBIOME AND DIET

Rob Knight, the Wolfe Family Endowed Chair of Microbiome Research at Rady’s Children’s Hospital of San Diego and director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation and professor of pediatrics, bioengineering, data science, and computer science and engineering at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), said that the dramatic reduction in the cost of DNA sequencing has enabled many of the new applications of microbiome research and generated an enormous amount of data. With all of these data comes the ability to build predictive models for many traits related to health and the microbiome. “Today, I can tell you with about 90 percent accuracy if you are lean or obese solely based on the DNA of the microbes in your gut,” said Knight. In comparison, using an individual’s DNA sequence to determine whether they are lean or obese is only 57 percent accurate (Knights et al., 2011; Loos, 2012).

Some microbiome patterns, said Knight, are so easy to understand that a human can decipher them without advanced computational techniques. For example, the microbiomes of individuals from Africa, South America, and the United States all converge from the infant to the adult stage within 3 years (Yatsunenko et al., 2012). That raises the question whether the microbiome is set by age 3, which his group addressed by examining microbiome samples from tens of thousands of citizen science participants. The results showed that the microbiome changes with age in adults are so subtle that humans cannot detect a meaningful pattern (de la Cuesta-Zuluaga et al., 2019). However, using the IBM AutoAI system, Knight’s group determined a person’s age to within 12 years from a stool sample, 5 years from a saliva sample, and 4 years from a skin sample. “Your microbiome provides a detailed readout of your age, just like many other biological clocks do,” said Knight.

One of his group’s projects involves applying this type of model to identify mismatches between a person’s biological and chronological age. If the biological age is notably higher, they may be unhealthy and at risk for various diseases. If it is lower, it may be possible to identify microbes that are protective factors against disease.

Knight said that ML has been used to relate the microbiome to nutrition. One study put 800 people on continuous glucose monitors and measured a

variety of factors that led to individualized glycemic responses to a defined sequence of meals (Zeevi et al., 2015). This enabled the researchers to isolate the effect of different foods on postprandial blood glucose response and show that the response for a particular person to a particular food varied greatly. One surprising finding was that for a sizable fraction of the cohort, rice was worse for their blood sugar than ice cream, and the microbiome was the best predictor of who was in which group.

These findings suggest that it might be possible, said Knight, to change the microbiome to put someone into the category of people who should eat ice cream instead of rice. Addressing metabolic issues that were rare but are now more prevalent may be possible through a better understanding of how nutrition affects the microbiome and today’s common chronic diseases.

Knight noted the concern about the connection between ultraprocessed foods and the increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and dementia, all of which ML models have shown to be closely linked to the microbiome. To better understand this connection, his group has been looking at how the microbiome and metabolome change throughout the body under different conditions. One experiment evaluated changes in the metabolome and microbiome of mice following a single dose of one of two antibiotics (Vrbanac et al., 2020). The surprise finding, said Knight, was that the antibiotics changed molecules throughout the body, showing that a spatial understanding of changes in the body has become increasingly important for microbiome research.

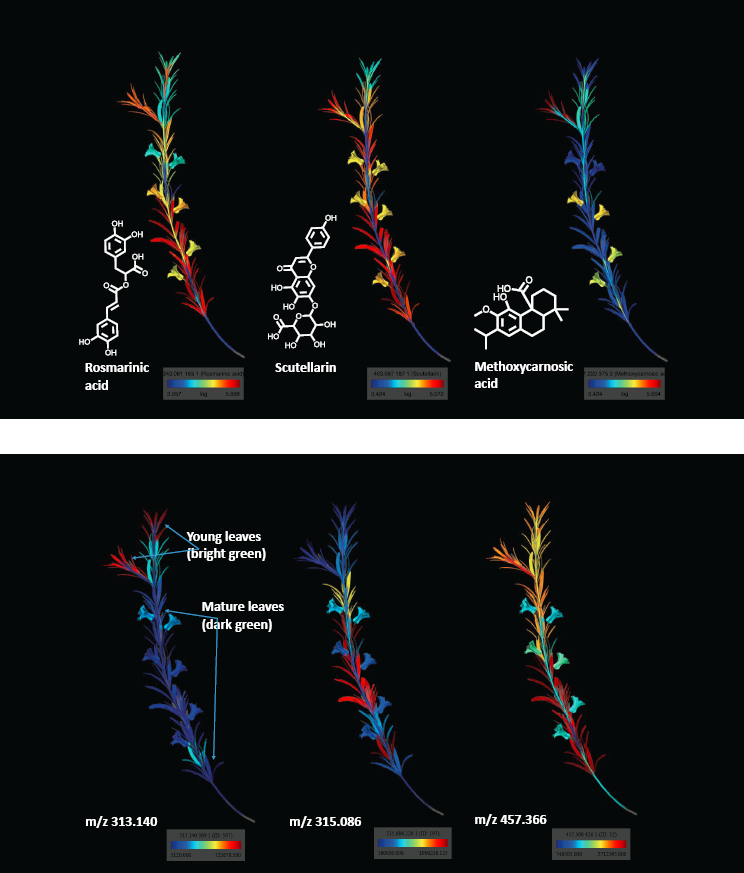

His team has been collaborating with a group in Italy to study the microbiome in a village of 300 centenarians. “We are looking for factors that improve health span and lead to very long residuals from the overall microbiome and metabolome aging models,” said Knight. One idea is that the bioactive compounds in rosemary somehow affect the microbiome and metabolome in a way that leads to a long life. A three-dimensional analysis of bioactive molecules in rosemary plants, measured using mass spectroscopy, found a specific spatial distribution of them throughout the plant (see Figure 3-2). This information can be useful, he said, for understanding the ethnobiology of how particular plants are used by various populations.

Knight and his collaborators launched the Global FoodOmics project to understand at the molecular level what is happening in the human body, cross-reference that to what is coming out of the body at the molecular and microbiome level as measured by the American Gut Project, and do meta-analyses to combine them. The work has provided insights into the profound transformation of foods by the microbiome as they pass through the gastrointestinal tract. Another finding has been the discovery of new bile acids produced by the microbiome with nonrandom distributions (Quinn et al., 2020). “This is an exciting direction toward understanding how microbes modify these bile acids, including with dietary components and

SOURCE: Presented by Rob Knight on October 10, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research.

in response to them, and modify a wide range of physiological properties that are linked to different medical conditions,” said Knight.

Using a new tool they developed, Greengenes2, Knight’s team and their collaborators solved the problem of being unable to reconcile microbiome data collected by two different methods (McDonald et al., 2023). They also searched for specific molecules produced by the microbiome, including in mixed samples, such as stool or food (Zuffa et al., 2023). In another project, his group has been looking at the connections between the microbiome and diet in Alzheimer’s disease, examining the effects of diets known to affect disease risk on microbiome and metabolome changes.

One early success from the Global FoodOmics project was demonstrating that they could read out an individual’s diet directly from a biospecimen via molecular analysis (Gauglitz et al., 2022). Molecular analysis of fecal samples easily distinguished between omnivores and vegetarians, for example. Using the same technique, Knight’s team is using a standardized test for verbal learning to identify particular foods that correlate with memory. Sugarcane and soda correlated with the most forgetting and worst ability to learn, and fish, strawberries, and mushrooms correlated with the best improvements in learning. A search of the literature found extensive evidence tying soda and sugar consumption to Alzheimer’s risk and memory loss and supporting the idea that fish is good for preventing Alzheimer’s disease and for memory in general. More limited studies have found that mushrooms and strawberries may also improve memory. “What is exciting is that with an afternoon on the mass spectrometer, we were able to recapture thousands of person-years of research across these different foods,” said Knight.

Knight is involved in the Nutrition for Precision Health (NPH) component of the All of Us Research Program, which aims to extensively genotype and phenotype 1 million Americans. The nutrition project involves three modules. The first is a detailed characterization of 10,000 people at baseline on normal diets. The second has the participants following three crossover diets at home, and the third has 500 people on specific diets in a clinical setting. “The reason why we need these three modules is that the first module is providing the big data for ML, the second module is providing intervention data for predicting the response, and then in the third module, we’ll be able to test the data with ground truth in a clinical setting,” said Knight. The overall goal is to take the resulting large dataset, distill it into something that is AI ready, and use ML to predict meal response curves, uncover relationships between diet-related diseases and individual metabolic phenotypes, and identify drivers of diet- and nutrition-related health disparities.

A second goal is to engineer bacteria from an individual, reintroduce them into the gastrointestinal tract, and alter “bad” microbiomes (Russell et al., 2022). One application of this, said Knight, would be to improve

cancer treatment efficacy in the two-thirds of people whose microbiomes render certain therapies ineffective. Groundbreaking research has demonstrated that dietary fiber and certain probiotics influence the gut microbiome and melanoma immunotherapy response (Spencer et al., 2021). However, this study also found that although fiber was beneficial, patients taking probiotics died earlier than those who did not. Caution is warranted, he said, in following recommendations for probiotics that have only been tested in healthy people.

Knight noted ethical considerations with microbiome interventions, particularly around bias in the training set, the ability to stratify the data, and how that stratification information is used equitably and safely. These same considerations likely apply to dietary interventions. Microbiome studies have also raised concerns about the safety of probiotics.

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF METABOLOMICS DATA TO INFORM PRECISION HEALTH

Susan McRitchie is the lead biostatistician and program manager in the Metabolomics and Exposome Laboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Nutrition Research Institute, and the concepts and results presented were from the Sumner Lab. She said that metabolomics is the methodology to study the low-molecular-weight complement of cells, tissues, and biological fluids. An individual’s metabotype is the signature, or biochemical fingerprint, of low-molecular-weight metabolites present in tissues or biological fluids and is ideal for studying precision nutrition and precision medicine (Sumner et al., 2020). The metabolomic signature comprises endogenous metabolites reflecting host and microbial metabolism and exogenous metabolites derived from external exposures throughout an individual’s life. “Metabolomics contributes to metabolic individuality because it encompasses all these complex interactions between the environment, the genome, our gut microbes, and xenobiotics,” said McRitchie. “The metabolic profile shows us the biologic perturbations in host and microbial metabolism, our internal exposome, as well as our life-stage exposures.”

McRitchie said that researchers frequently use metabolomic studies to discover biomarkers, including early-stage biomarkers that provide an opportunity to intervene early in the disease process and biomarkers for monitoring therapeutic response. Common biospecimens include urine, serum, and plasma, but saliva, hair, fecal samples, and breath can also provide useful data. Metabolomic studies can be hypothesis driven, to answer a specific question, or data driven, using ML to identify patterns. Researchers can use that information to design a study question. Metabolomic data can be analyzed alone or incorporated with other ’omics data.

Model systems and human subject investigations, said McRitchie, have shown that the metabotype correlates with sex, race, age, ethnicity, polymorphism, stress, weight status, mental health status, blood pressure, many disease states, the gut microbiome, diet, and physical activity. Each factor contributes to differences in levels of endogenous metabolites, which can be considered differences in internal exposure. Many chemicals, drugs, medications, and nutrients can affect the endogenous metabotype, and many can be analyzed simultaneously with host and microbial metabolites using untargeted methods. Metabolomic studies can provide mechanistic insights from pathway analysis that can identify pharmacologic targets, nutritional interventions, and genetic links to disease.

McRitchie explained that investigators acquire metabolomics data primarily from nuclear magnetic resonance or mass spectrometry, and both methods can use a variety of biospecimens. A targeted method will focus on a particular set of analytes or pathways, and an untargeted method can detect 10,000–40,000 signals. Techniques such as principal component analysis are good at reducing the dimensionality and visualization of the data. Various supervised methods can identify features important to a specific phenotype. In addition, researchers now use a variety of ML and DL methods, including random forests, neural networks, and even some deep learning models, to analyze the data.

In one study, a collaboration between the Sumner Lab and Harvard University, McRitchie used logistic regression analysis to find an early biomarker of placental abruption (PA), a rare but serious disorder of pregnancy that has no universally accepted diagnosis (Gelaye et al., 2016). The earliest but nonspecific symptoms include vaginal bleeding that occurs in some patients in the third trimester. The study’s goal was to identify biomarkers from second-trimester serum that protects against PA in the third trimester. Using the Biocrates AbsoluteIDQ® p180 kit, which allows for the simultaneous quantitation of up to 188 endogenous metabolites, 9 metabolites were significantly associated with PA; they used 2 in the final model.

Logistic regression modeling for the probability of PA using vaginal bleeding in the third trimester as the predictor had an area under the curve (AUC) of 63 percent, whereas modeling with the two metabolites had an AUC of 68 percent. This was not a statistically significant increase, so it may initially seem unimportant, said McRitchie, but the key is that the latter is a second-trimester biomarker for PA in the third trimester. Further investigation into how the two metabolites are connected mechanistically to PA found that low levels of choline, known to be associated with pregnancy complications, might be a factor in PA. “It is possible that PA could be mitigated by increasing choline early in pregnancy or for women of childbearing age,” said McRitchie. “This needs to be replicated in another cohort, but it is a promising result.”

McRitchie briefly discussed the concept of the exposome in precision nutrition. Exposome research is key because it provides an understanding about how exposures and changes in endogenous metabolism are linked to an individual’s genetics and states of health and wellness. Pathway perturbations, she said, can help identify potential targets for nutritional and pharmacologic interventions.

To conduct exposome studies, the Sumner Lab and others use mass spectrometry for untargeted analysis, and the lab uses open-source software to preprocess the data and rapid algorithms to match signals in the mass spectrum to an in-house library of over 2,500 compounds and to public databases. In addition to essential nutrients, this method detects host and microbial metabolites, environmental metabolites, drug and medication metabolites, essential nutrients, and food metabolites. Simultaneously detecting metabolites is crucial, said McRitchie, because healthy biochemistry depends on essential nutrients, which serve as cofactors for hundreds of biochemical reactions, play a role in transcription, are antioxidants, and are involved in many specialized functions. Different exposures, she added, can affect the speed of metabolism and how the body absorbs or transports nutrients and vitamins. Responders and nonresponders are important in precision nutrition, McRitchie noted, because individuals have different nutrient requirements and can have different responses to nutrient intakes. An individual’s response is going to be related to their exposures, health status, and their genetics, she stated, and studying how people respond allows for discovering mechanisms and identifying nutritional targets.

One study, a collaboration among the Sumner Lab, University of Tehran, National Cancer Institute, and National Institute on Drug Abuse, aimed to find an objective marker of opium use disorder to supplement the qualitative diagnostic criteria and provide insights into mechanisms for developing intervention strategies (Ghanbari et al., 2021; Li, Y. et al., 2020). Her team analyzed urine samples from users and nonusers and found mass spectrometry signals differentiating the two groups, including perturbations in vitamins and vitamin-like compounds, neurotransmitter metabolism, Krebs cycle metabolism, glucogenesis, one carbon metabolism, lipid metabolism, and environmentally relevant metabolites. Validation of this metabolic signature might find use as an objective biological marker of opium use disorder and render it possible to develop a nutrient cocktail capable of mitigating addiction.

McRitchie discussed another study involving both metabolomics and microbiome data that aimed to identify biomarkers for and pathways involved in osteoarthritis (Loeser et al., 2022; Rushing et al., 2022). Untargeted analysis of fecal samples from individuals with obesity and with or without osteoarthritis found metabolic disruptions related to intestinal permeability, perturbations related to precursors of polyunsaturated fatty

acids, such as omega-3, levels of the short-chain fatty acid propionate, which is produced by microbes in the colon and associated with dietary fiber intake, and levels of glucosamine, a component of cartilage. These findings suggest a possible nutritional intervention based on the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids, dietary fiber and protein, and supplementation with glucosamine and short-chain fatty acids.

A data-driven correlation analysis identified a link between osteoarthritis, gut microbes, and environmentally relevant metabolites, inflammation markers, and endogenous and microbial metabolism. One signal matched that of an insecticide associated with a particular herbicide, and others matched to compounds abundant in fruits and vegetables, suggesting that they could be the source of exposure to the herbicide. The insecticide also correlated with gut microbes from a phylum that produces short-chain fatty acids, consistent with the earlier findings.

McRitchie mentioned specialized repositories for metabolomics data, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Metabolomics Workbench1 that accepts both untargeted and targeted data and has publicly available data from over 2,000 studies. Several large-scale NIH consortia are also including metabolomics data, including the NPH,2 Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity,3 Human Health Exposure Analysis Resource,4 Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes,5 and Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine.6 These repositories include both metabolomics data and metadata. Metadata have data privacy issues, however, and one way the consortia are dealing with this is to keep the metadata in their data center and store metabolomics data on the Metabolomics Workbench.

In addition to Metabolomics Workbench, McRitchie noted that public databases for metabolite annotations include FoodDB;7 Phenol-Explorer, with annotations of over 500 polyphenols;8 PhytoHub;9 and the Human Metabolome Database,10 with annotations for over 220,000 metabolites. Publicly available data analysis resources also include MetaboAnalyst.11

___________________

1 Available at https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org (accessed January 9, 2024).

2 Available at https://www.researchallofus.org/data-tools/workbench (accessed January 9, 2024).

3 Available at https://motrpac-data.org (accessed January 9, 2024).

4 Available at https://hhearprogram.org/data-center (accessed January 9, 2024).

5 Available at https://publichealth.jhu.edu/echo (accessed January 9, 2024).

6 Available at https://topmed.nhlbi.nih.gov/topmed-data-access-scientific-community (accessed January 9, 2024).

7 Available at https://foodb.ca (accessed January 9, 2024).

8 Available at http://phenol-explorer.eu (accessed January 9, 2024).

9 Available at https://phytohub.eu (accessed January 9, 2024).

10 Available at https://hmdb.ca (accessed January 9, 2024).

11 Available at https://www.metaboanalyst.ca (accessed January 9, 2024).

APPLICATIONS OF AI IN NUTRITION RESEARCH

Benoît Lamarche said that AI applications in nutrition research include increasing the field’s capacity to manage and analyze big datasets, dietary assessment, predicting outcomes, and social media content analysis. Calling nutrition a “traditional field,” he said that the challenge to realizing these applications’ potential will be breaking the mold and adapting to new methods.

In the first example of an AI-based application for nutrition, Lamarche discussed a tightly controlled feeding study in which men and women with metabolic syndrome ate a North American diet for 5 weeks and then a Mediterranean diet for 4 weeks to determine the effect on the metabolome. The goal was to develop an ML algorithm that classifies people according to their diet based on untargeted metabolomics data. The resulting algorithm was 99 percent accurate, far better than the typical published study, and it showed the value of having full control of the diet, which generates a much cleaner dataset. When Lamarche and his collaborators repeated the experiment with self-reported dietary intake data, the dataset had much more noise, and the accuracy of the same ML algorithm dropped by almost 20 percent.

The lesson from this study, said Lamarche, is that the signature may not be accurate when using either untargeted or targeted metabolomics without carefully controlling the diet. This is an important issue because most of the published studies of this sort rely on self-reported dietary intake data. “It is going to be a challenge to make sense of all of this at the end of the day because we know the accuracy of these signatures in terms of predicting the right diet is going down as there is more noise in the data,” he said.

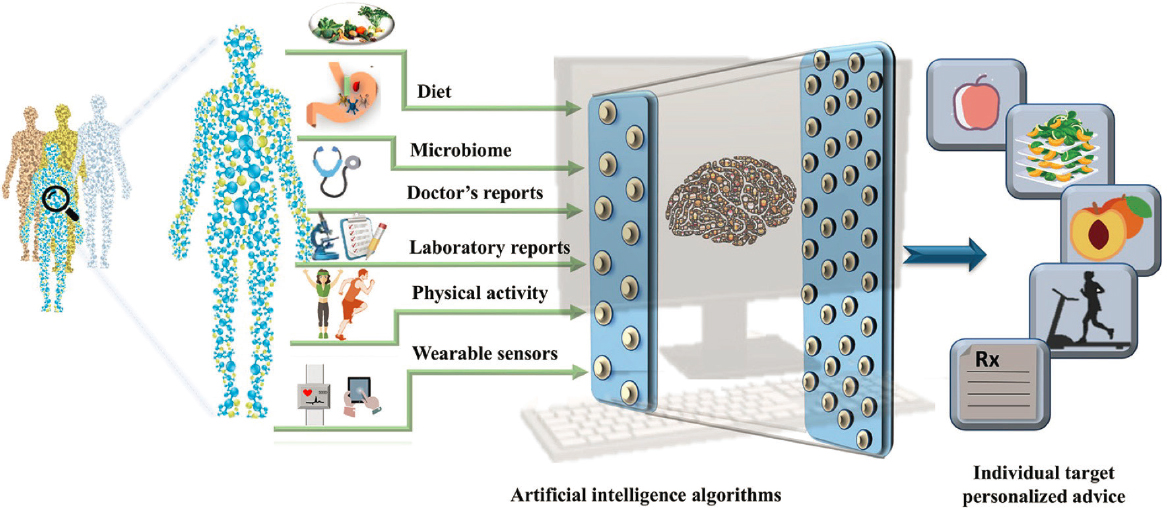

Lamarche explained that for precision nutrition, the idea is to use all the data available from one individual to predict a health outcome. One study, for example, put prediabetic individuals on the Mediterranean diet or a personalized postprandial management diet based on information from microbiome data, blood tests, questionnaires, anthropometrics, and food diaries (Ben-Yacov et al., 2021). Creating the personalized diet relied on an ML algorithm that integrates these data to predict postprandial glucose responses, and the mean daily glucose levels and postprandial glucose levels were significantly lower in this group, showing that using more data to personalize the intervention was working. The challenge, said Lamarche, is figuring how to implement this type of intervention in clinical practice.

As an example of how AI can benefit precision public health, Lamarche discussed a study that characterized and mapped local environments depending on the relative proportion of low-quality food offerings to supermarkets and compared that to a map of socioeconomic status and dietary habits from Web-based dietary intake data. The ML model developed from these data could identify where people have a low-quality diet and live

in a low-quality food environment. From a public health perspective, this type of mapping model can identify those areas where the environment is unfavorable to high diet quality and develop interventions that change the environment of those areas. One caution, said Lamarche, is that these maps could lead to stigmatization of different neighborhoods.

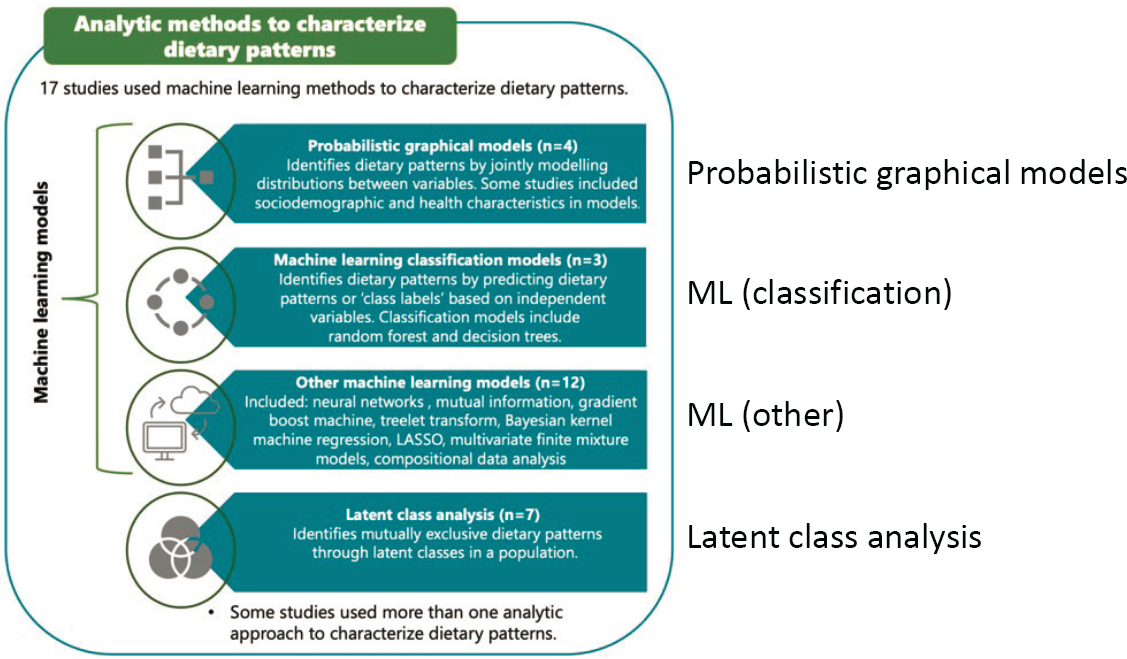

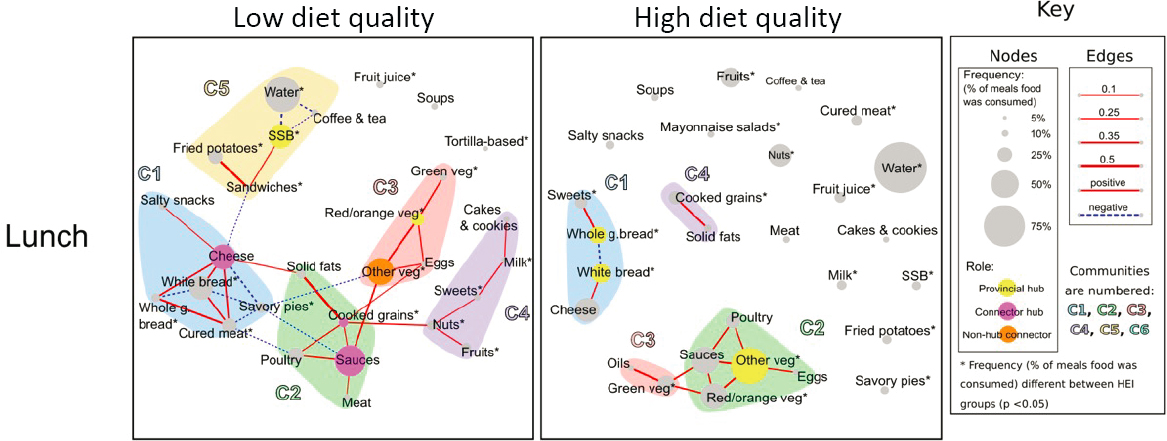

Lamarche noted that a variety of AI and ML methods can provide a better understanding of dietary patterns (see Figure 3-3). One study, for example, constructed a food network to understand meal patterns in pregnant women with high- and low-quality diets (see Figure 3-4) (Schwedhelm et al., 2021). The investigators used the Louvain community algorithm, which can detect communities in large networks to identify relationships among the different foods and communities of foods consumed together at different meals. The low-quality diet group had certain patterns of intake, such as consuming cheese more systematically with white bread.

Lamarche said that the current thinking is that AI will improve the ability to predict outcomes, although this idea is based mainly on studies with clear outcomes—disease positive versus disease negative, for example. For clear-cut outcomes, AI may indeed perform better than traditional statistical models. However, nutrition data are more “noisy,” and if the outcome is a prediction of dietary intake, AI results may become murky. His group measured dietary intakes using repeated Web-based 24-hour recalls and compared the accuracy of classical logistic regression and a variety of ML methods in predicting vegetable and fruit consumption (Côté et al., 2022). Prediction accuracy for all methods, including logistic regression, was low, approximately 60 percent even with models using information from hundreds of variables. Tweaking the ML models to try to make them more appropriate for the data had little effect. In addition, the ML models and logistic regression model retained different variables. If the goal is not just to develop an accurate model but to understand which set of variables predict adequate consumption, the answer will depend on the model, which is a problem. “We tried to understand why the models were not retaining the same variables to predict the consumption of vegetables and fruit with the same accuracy, but we could not find the reason,” he said.

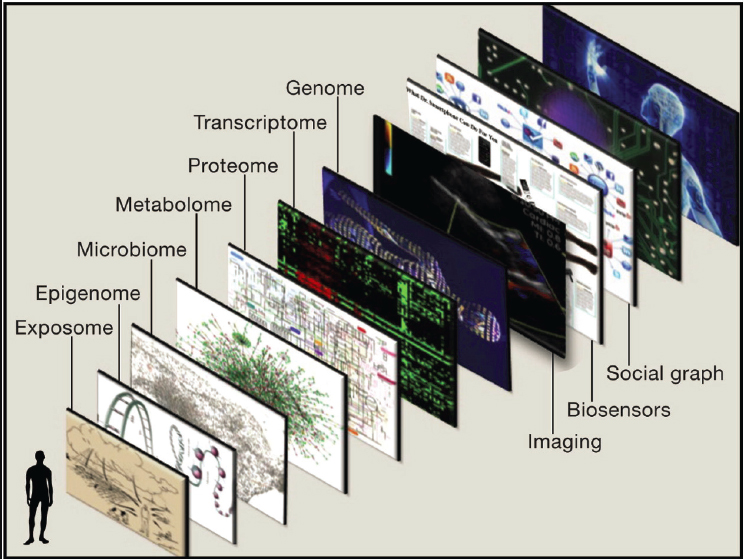

Another example of how AI can contribute to nutrition research is exploring the relation of social media content to different food consumption patterns in different populations, said Lamarche. One study, for example, looked at tweets related to foods in Canada to assess health activity and nutritional habits (see Figure 3-5) (Shah et al., 2019). Many challenges exist to using these data, however. For example, a tweet stating that someone is a tough cookie would need to be scrubbed from the dataset, which would require a great deal of work. “When you start doing these kinds of analyses, you are going to spend 80 to 90 percent of your time cleaning the data before you can actually run something,” said Lamarche.

SOURCE: Presented by Benoît Lamarche on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research. (Reprinted with Permission from Sharon Kirkpatrick.)

SOURCE: Presented by Benoît Lamarche on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Schwedhelm et al., 2021.

SOURCE: Presented by Benoît Lamarche on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Shah et al., 2019.

Lamarche said that AI has great potential for the nutrition field but also significant challenges, such as appropriately considering data quality, developing a common language between nutrition and computational science, and standardizing methods and approaches. He recommended keeping an open mind about what AI can and cannot do to address what is important in nutrition.

DESIGNING NUTRITION STUDIES FOR AI DATA ANALYSIS

Sai Krupa Das, senior scientist on the Energy Metabolism Team at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging and professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, said that the growing intersection of AI and nutrition research provides exciting opportunities for streamlining conventional research protocols and revolutionizing clinical nutrition applications. Although the size of the task can seem overwhelming, she believes it is a great time to convene to explore the opportunities. AI, she said, can be especially useful in analyzing complex data, informing adaptive study designs, and providing personalized nutrition interventions. However, these advancements come with challenges that must be addressed by multidisciplinary teams.

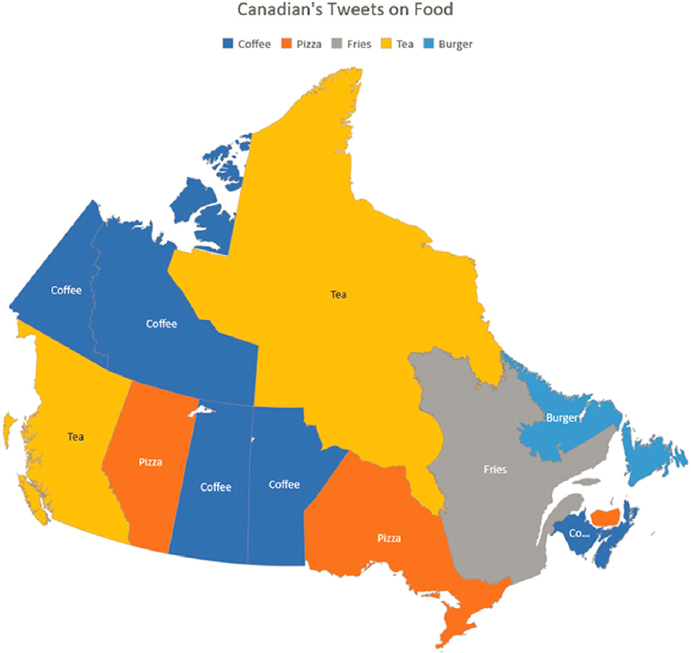

In Das’s view, much of the difficulty in crafting personalized nutrition recommendations lies in understanding the interplay among internal (e.g., microbiome, genetics) and external factors (e.g., diet physical activity) that produce variations across individuals. Approaches are primarily in fields such as genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, but a comprehensive understanding requires an integrated, systems-wide approach (see Figure 3-6) (Verma et al., 2018). For disease prevention, studies investigating variable responses to the same intervention also must also quantify the unique responses from people in various disease states. Nonetheless, she said, a tremendous opportunity exists to address these components and convert the challenges into real science that informs human health. “The time is certainly now. However, instead of dismissing the process as ‘garbage in, garbage out,’ AI inputs need to be carefully managed, and the algorithms need to be thoughtfully trained. We need to improve our methods, improve our processes, improve our workflow, and improve our infrastructure,” said Das.

For nutrition scientists such as herself, the first challenge to overcome is to move away from a reductionist, hypothesis-driven approach to research design that examines singular biological pathways or outcomes. Rather, said Das, nutrition research needs to investigate the dynamic interactions between pathways that are not always linear. For example, a study of time-restricted eating and weight, stratifying early and late eaters, found no significant group difference in weight loss effectiveness (Garaulet et

SOURCE: Presented by Sai Das on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Verma et al., 2018.

al., 2013). However, when genetic predisposition was factored into the analysis, approximately 5 kilograms of weight loss separated individuals with one variant of the PLIN1 gene versus another variant, suggesting the importance of multiple factors that may help explain response variability or intervention efficacy (Garaulet et al., 2016).

Das noted that over the past 2–3 decades, data have been collected on a variety of factors but that the challenge has been that such data exist in silos. “What we need is to set up study designs and infrastructure where there is multiscale input built in from the start and data integrated within one platform,” said Das. Multiscale data include genetics, age, race, ethnicity, microbiome, the built environment, medication use, the biological clock, diet, medical records, and lifestyle, physiological, and social behaviors. She noted that the core requirement of a personalized nutrition computational infrastructure is that it needs to be classified and identified as a food and health infrastructure. It requires four components: the determinants of food choice, past and current intake of food and nutrients, status and functional markers of nutritional health, and health and disease risk (Snoek et al., 2018). Hard research infrastructures, or toolkits, and technical equipment for AI-powered nutrition research include applications, devices, digital health, wearable technology, digital medicine, and digital therapeutics; soft research infrastructures include telehealth or telemedicine, health information technology, and Web-based assessment using a cloud-based data source (McClung et al., 2022).

Managing and implementing the food and health infrastructure for designing studies should be user-driven, said Das, and should include the following:

- nutrition bioinformatics structures, including all biologically relevant data, preprocessed ’omics data, and descriptive and study participant phenotype data, with a priority of processing n-of-1 data;

- data management;

- data processing that includes an informatics infrastructure with standardized food intake monitoring;

- data-sharing capabilities; and

- platforms, such as web portals, for publishing the data derived from the studies to a bigger community (Verma et al., 2018).

“These are all important components in study design, and they need to be built in while the study is being designed and while the infrastructure is being put together, rather than afterward, as retrofitting these components will not work right,” said Das. Establishing a food and health infrastructure for designing studies, she added, will ensure that the data related to food

constituents, intake, energy expenditure, environmental variables, determinants of health, and disease risk are all in one place. These data can help elucidate the determinants of behavior that can be used to develop prediction algorithms and nutritional interventions (Verma et al., 2018).

Das listed several considerations regarding data collection when designing a study. For dietary data, these include the methodology, whether food intake diaries, 24-hour recalls, questionnaires, devices, or apps; biases in recall, reactivity, reporting, and portion size; adherence to the study protocol and related definitions, data collection, and data reporting; tools, including devices, apps, and measures or reference standards; and standardized databases that include ethnic foods and sync with other measures. Similarly, assessing physical activity has important considerations, such as how to deploy questionnaires, tracking apps, and wearables and clean and integrate the data. Considerations for biospecimen collection include biospecimen type, whether measurements are continuous or snapshots in time, specimen processing, and analysis that includes relational data and accounts for intra- and interstudy differences.

Although AI is useful for ’omics analysis, it may be important to capture all the ’omics measurements to help with phenotyping or deeply characterizing individual responses to an intervention or exposure. For example, a change may occur at the transcriptome but not the genome level and may be interpreted differently without the comprehensive measures. Das noted the importance of thinking about each input carefully when planning a study, from its design to conception to the choice of the data source and integration with the data infrastructure.

Electronic health record (EHR) data are important because they help with the human continuum from diet to wellness. However, the multiple components of an EHR contain a great deal of complexity, including sensitive information, data heterogeneity, and data structure. The benefits of digitized records include complete relational data for each person and across participants and cases, but a priori communication between AI and clinical teams is essential to ensure the data can be merged with other data collected in a study. Digitization comes with challenges such as improper standardized formats, a lack of user interface training, and poorly designed technology that leads to errors in the record. Das said that data standardization can make updating these datasets more feasible and improve communication between clinical sites. Without data standardization and harmonization, it is not possible to build a good AI-ready dataset, she added.

Das said that human studies will always have missing data, which can lead to biased and misleading results. Imputation methods can address missing data, but each method has its own drawbacks. Substituting mean or median values, for example, introduces bias for extreme values, and the K-nearest neighbors algorithm, in which values from grouped individuals

can be averaged and assigned to the missing variable, may fail if individuals cannot be clearly grouped based on their clinical record values. An iterative process known as “multiple imputation by chained equations,” which considers relationships between variables, is computationally intensive and assumes normally distributed data. Excluding data that are not normally distributed also can lead to bias. Das recommended consulting modelers before study implementation to establish ways of handling missing data.

An absolute must, said Das, is taking a team science approach for generating AI-ready data. Adapting to the widespread use of data-driven technologies will require supporting this approach and developing professionals with clinical and computational skills. Engaging the research team in all aspects of a project, from inception and planning to completion, analysis, and interpretation of findings, is important and will help integrate experts in all relevant fields to provide insights from diverse perspectives. Das recommended engaging data scientists as integral peer collaborators. Multidisciplinary training and education also are critical for building interdisciplinary teams, as is emphasizing that AI is a tool to inform study designs and facilitate decision making rather than a replacement for human experts.

Today, said Das, AI is informing iterative adaptive study designs (Pallmann et al., 2018). For example, a calorie restriction study might start with a meal plan. Based on a survey of preferred foods collected at baseline and analysis by an AI algorithm, researchers would then iteratively revise and customize the meal plan to maximize individual success with adherence.

Das said that the age of big data provides exciting opportunities to integrate data on food consumption and EHRs to create synthetic human cohorts that can be used to predict responses to nutrition recommendations at the system level. One primary goal for personalized nutrition, she said, is to create predictive models that draw on history of monitored health responses. The pie-in-the-sky vision, she said, is to create a geographic information system of a human (see Figure 3-7) (Topol, 2014).

AI AND THE BIG CHALLENGES IN AGRICULTURE AND FOOD

Aaron Smith, the DeLoach Professor of Agricultural Economics and lead of the AI Institute for Next-Generation Food Systems (AIFS) socioeconomics and ethics cluster at the University of California, Davis, said that the increase in agricultural productivity over the past century has been massive. In fact, U.S. farmers now produce four times as much with almost the same inputs as 100 years ago, and the world produces 250 percent more cereals on only 15 percent more land (Our World in Data, 2023; Pardey and Alston, 2021). Production, he added, has outgrown global population increase over that time.

SOURCE: Presented by Sai Das on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Topol, 2014.

Smith said that higher productivity has led to lower prices, down 50 percent since 1960 on an inflation-adjusted basis. As a result, food now accounts for a much lower percentage of U.S. household budgets. Although productivity has improved the most in rich countries, the percentage of people in developing countries experiencing undernourishment has fallen by 65 percent. However, lower food prices and the availability of convenient ultraprocessed food means people eat more, resulting in over half the population in Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development countries being overweight and nearly 25 percent obese (OECD, 2019). Over the next 30 years, these countries will spend 8.4 percent of their health budgets to treat the consequences of so many people being overweight, said Smith.

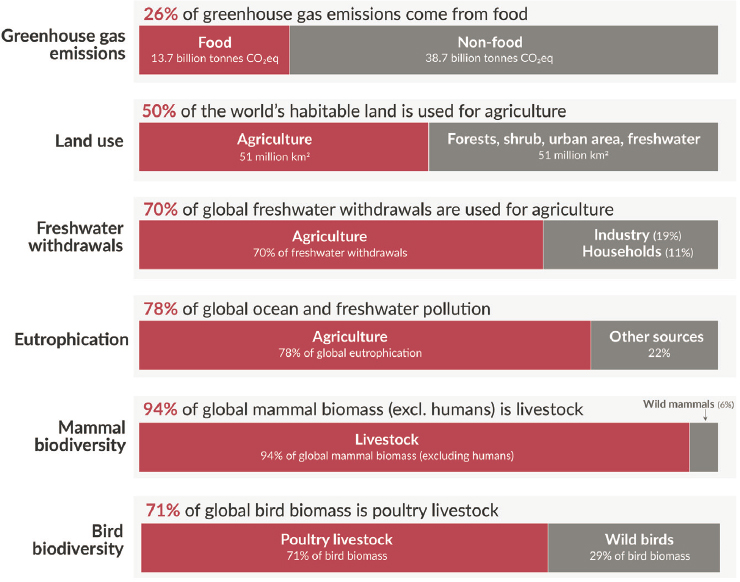

Food production is not benign, and it significantly affects the environment, said Smith (see Figure 3-8). Converting virgin land to crops, for example,

SOURCE: Presented by Aaron Smith on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Ritchie et al., 2022.

causes massive carbon losses from soil and increased greenhouse gas emissions. Excess fertilizer application pollutes waterways, and livestock produce copious amounts of methane. Smith noted that because the global population is still increasing, food consumption will increase in the decades ahead. Perhaps more relevant, he said, is that global incomes are increasing, and as people get richer, they tend to consume more resource-intensive foods, such as beef.

One worrying sign, said Smith, is that productivity growth has slowed for the six grains responsible for the large majority of calories consumed worldwide. Continuing to increase productivity on the agricultural side is imperative to meet future calorie demands; otherwise, more virgin land will be cleared. This would exacerbate agriculture’s environmental challenges.

As an economist, Smith frames this problem in terms of externalities, a side effect or consequence of an economic decision an entity makes. For example, micro-decisions in the moment about what and how much food to consume have consequences that the person’s future self bears. Similarly,

society bears much of the cost of health care even though individual actions largely influence one’s health and thus care costs, and farmers realize the benefits of fertilizing their crops but do not bear the cost of the pollution to rivers and streams. Data are a positive externality, Smith explained, as the benefits also flow beyond the provider.

The standard Economics 101 response to externalities is to consider imposing taxes so people see the real cost of their actions when they make decisions. “I do not see any way to make that work for our food consumption decisions,” said Smith, because most decisions that create these challenges are hard to change given the strong habitual element to eating and the subconscious decisions that inform eating behaviors. Although sugar taxes, for example, contribute at the margin to help people consume less sugar, manipulating human decisions by changing prices is unlikely to solve these problems, he said.

Smith said that public funding of ethical technologies to benefit society is imperative, particularly to solve problems arising from negative externalities and supercharge positive externalities. Regarding ethics and technology, he listed three core questions: who wins and who loses, who bears risk, and who decides. To Smith, the important point is that regulators’ ability to constrain the development of various AI tools is limited. “It is limited by the amount of control that you have, and even if you believe that you might have a lot of control within your own country, you probably do not have control outside of your own country,” said Smith.

For Smith, the ethical approach requires proactive decisions to develop technologies that would benefit society rather than focusing on regulation. “Do not pretend that by some sort of regulation and rulemaking that you are going to end up with ethical technology,” said Smith. Examples of AI-enabled technologies relevant to agriculture include autonomous weeders, precision seeding and fertilizing, supply chain optimization, automatic detection of pathogens in food processing, diet customization tools, and engineering healthy foods.

When Smith and his collaborators interviewed AIFS AI researchers, the respondents expressed confidence in academic research practices and outcomes and were skeptical of the private sector, which often rushes technologies into the marketplace too quickly (Alexander et al., 2023b). The researchers commented on the complex landscape they must navigate to get data, comply with regulations, and test and deploy products. Sometimes, they reported, trustworthiness makes an AI tool less likely to be used, with the idea that it is better not to know the information that AI-generated data would reveal, such as the presence of contaminants (Alexander et al., 2023a).

Smith and his colleagues also surveyed 1,000 Illinois corn and soybean farmers to better understand their concerns about sharing data. Nearly

half the farmers were unconcerned, and most of those who were concerned gave multiple reasons, including others making money off them, the top reason; an invasion of privacy; and being unsure how the data will be used. His group also asked farmers about whether they would use AI-powered technology. They voiced concerns about regulatory burdens, labor scarcity, and finance pressures. The main barriers to adoption are not related to trust issues but whether AI will solve real-life problems. “I think the same is probably true for consumers on the food side if we think about various technology tools to improve eating behaviors,” said Smith.

Smith said that the priority should be to invest in problems beset by externalities and develop technologies that can help surmount the challenges of human behavior: “I think that is a much better path than trying to figure out ways to manipulate human behavior.”

NOURISH OR PERISH:

A RESEARCH JOURNEY THROUGH FOOD SUPPLY CHAINS

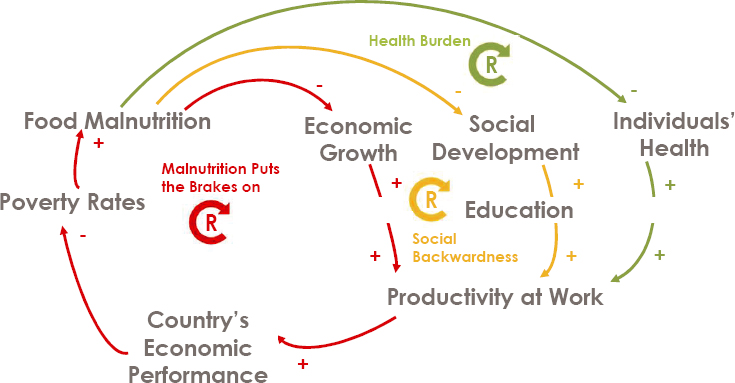

Christopher Mejía-Argueta, research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Center for Transportation and Logistics and founder and director of the MIT Food and Retail Operations Lab, noted that malnutrition affects other things besides health, including economic growth, social development, productivity at work, and a country’s economic performance (see Figure 3-9). Moderate food insecurity affects some 1.25

SOURCE: Presented by Christopher Mejía-Argueta on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research.

billion people worldwide and 143 million in Latin America and the Caribbean, and severe food insecurity affects 746 million people worldwide and 62 million people in Latin America and the Caribbean (FAO, 2020). Mejía-Argueta added that although the workshop’s focus was on food, future challenges will involve water and seed availability.

Mejía-Argueta and his colleagues are tackling the challenge of malnutrition by creating innovative strategies to address the related problems of food waste or loss across the supply chain, from the field to the grocery store or farmers’ market, and focusing on food safety and stakeholder behavior. He noted that technology works as an enabler, and it is important to provide good governance and policies that will be helpful for all population segments.

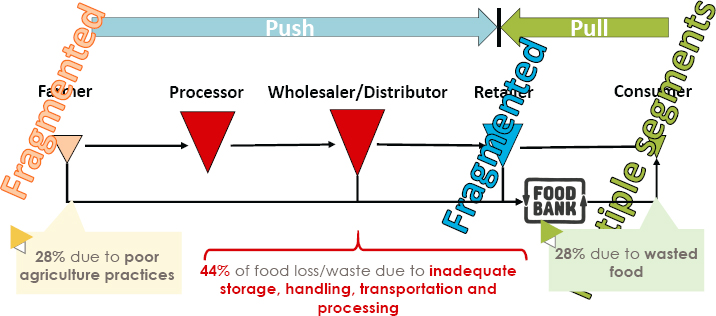

Supply chain management, said Mejía-Argueta, is “the systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole” (Mentzer et al., 2001). The supply chain starts with obtaining the raw materials for a product via a supplier. The manufacturer generates the product and ships it with others to a decoupling point to gain economies of scale. Usually, that point is the retailer or wholesaler, but the distributor is in charge of the decoupling. Mejía-Argueta said that the main challenge is perishability. AI and ML algorithms are embedded in the supply chain in the decision-making processes that connect the (forecasted and actual) order and inventory being managed to the consumer. AI and ML may help predict how a consumer will behave, how changes in the supply chain can affect nutrition, and how supply shocks may affect the yield and other parts of the upstream value chain.

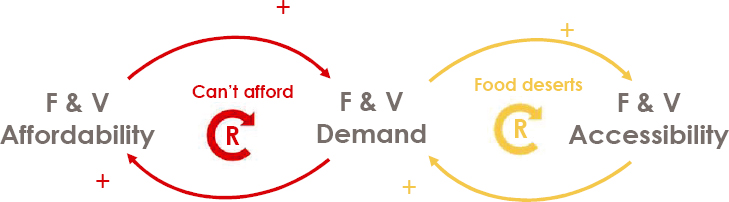

Mejía-Argueta noted that moderately food insecure people in Latin America and the Caribbean need to pay 50 cents more per day to eat than people who are moderately food insecure in the rest of the world. Similarly, severely food insecure people in Latin America and the Caribbean pay 21 cents more per day. The reason, which also holds true in U.S. food deserts, is the negative polarity in the feedback between demand and affordability and between demand and accessibility. This dynamic makes food and vegetables expensive and hard to find and purchase for a low-income population (see Figure 3-10). For example, if a food item is too expensive to buy, shopkeepers will order less, affecting both affordability and accessibility. He noted that $3 will buy 312 calories of fruits and vegetables and nearly 3,800 calories of ultraprocessed, nonnutritious food.

The food supply, said Mejía-Argueta, is mostly inventory pushed and depends on many intermediaries (see Figure 3-11). Farmers are typically

NOTE: F & V = fruit and vegetable

SOURCE: Presented by Christopher Mejía-Argueta on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Sanches and Mejía-Argueta, 2019.

SOURCE: Presented by Christopher Mejía-Argueta on October 11, 2024, at the workshop on The Role of Advanced Computation, Predictive Technologies, and Big Data Analytics in Food and Nutrition Research; Sanches and Mejía-Argueta, 2019.

fragmented, particularly smallholder farmers, who account for most of the diversity in the food supply. Retailers and consumers are also fragmented. The result is that farmers account for 28 percent of food loss because of poor agricultural practices and lack of visibility, and consumers waste another 28 percent due to overpurchasing. The remaining 44 percent of food loss and waste occurs because of inadequate storage, handling, transportation, and processing.

One example of his work focused on agribusiness and involved developing an exploratory model to understand how the market size or directness to the market may affect farm gate prices. This project aimed to model how these mediators explain potato prices in Peru (Noriega et al., 2021). Mejía-Argueta noted that a big challenge, as with many modeling efforts, is having granular, high-quality data. For this study, data came from Peru’s Ministry of Production and the Ministry of Agriculture, but those data do not capture what the farmers are thinking or the context around their decision-making processes. “That empathic approach is important to build the system or models from the bottom up,” he said. Farmers, he added, will not use a top-down model.

The research questions Mejía-Argueta answered were to identify the factors that connect or better explain the connectivity between the market and the smallholder farmers, 80 percent of whom own less than five hectares; determine how market channel directedness or market size access affects the farm’s gate price; and identify the direct or indirect influence of different factors on gate price. He explained that associativity is a critical component of market channel directness; however, it must be carefully understood to drive effective intervention schemes.

One takeaway from this project is the mixed effects on factors positively related to market directedness and negative effects on farm prices. Mejía-Argueta and his team suggest that multiple price-equilibria points exist and a geographical analysis is needed. Another lesson learned was not to overlook the importance of local demand. Larger markets do not necessarily imply higher prices, but establishing more local markets may. A further lesson was that information is not necessarily related to market accessibility or realizing a better price and that having data but possibly no real choices makes information nonactionable.

As a final example, Mejía-Argueta presented his study to increase nutrition in India by bringing more plant-based protein to the millions of people living in food insecurity whose diets lack protein, given their carbohydrate-rich diet based on rice and wheat, which the government distributes nationwide (Das, 2021). This project allowed his group to run a successful experiment to balance the production and distribution of pulses and cereals to improve the diets of each Indian state following the principle of grow local, eat healthy locally.

Elenna Dugundji, a research scientist at the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics and a collaborator of Mejía-Argueta, briefly described several projects she has worked on with him. She discussed a project on food waste in the airline industry that combined data analytics and ML algorithms with a system dynamics framework to minimize cost and maximize the use and preservation of resources for a global airline catering company. The team also used unsupervised learning to cluster the different airports together, resulting in a more robust analysis.

Dugundji and Mejía-Argueta are investigating the effects of global supply chain disruption on U.S. food security, including whether U.S. food imports during the pandemic shifted toward being sourced over land from Latin America and/or using noncustomary maritime ports when the supply from overseas was disrupted and U.S. maritime ports were severely congested. If a shift did occur, did it persist after the pandemic ended? Another question they are studying is whether maritime ports are interchangeable in handling perishable commodities. For example, if the Port of Wilmington is disrupted, can its volume of banana imports be readily handled at a nearby port, or would this require more drastic rerouting of import flows and/or lead to food shortages at certain locations? The analysis uses a directed graph network, connecting export locations from outside the United States to import locations in the United States.

REACTION TO THE PRESENTATIONS ON APPLICATIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED

Becca Jablonski, codirector of the Food Systems Institute and associate professor at Colorado State University, noted that the potential of omitted variable bias or not considering the importance of relationships when building models are always present. She tries to deal with these by grounding conversations in the community. Regarding missing data, she called for focusing more on getting the best data possible for tipping points. The opportunity also exists to leverage unsupervised learning, especially with missing data. For her work, getting information along the supply chain is the hardest piece; good data at the farm level and decent data for the retail end of the supply chain are available, particularly for acquisition and purchasing. Supply chain data, however, are proprietary.

One of her projects is looking at the effects of policies related to food in schools and how schools respond to them. Obtaining information on what school meals look like before and after a policy goes into effect could eliminate the need for additional data collection. She also wondered about ways to use wearable technology to save time and effort required for data collection. She wants to learn more about how AI can support adaptive study designs.

Jablonski said that one of her big concerns in leading big modeling efforts is that she has not found a way to bring the best disciplinary science and robust methods to large interdisciplinary modeling projects. It is important, she said, to ensure that models reflect actual production systems in a given region. She noted that the modeling field is getting papers published in top interdisciplinary journals but not top disciplinary journals.

Regarding data, Jablonski reiterated the need to preprocess data, which requires human judgment. She noted that a lack of data can make it chal-

lenging to support historically disadvantaged and underserved farmers and ranchers without exacerbating challenges, suggesting that the federal government needs to rethink its data collection efforts. It may be fruitful, she said, for the government to invest in web scraping to get supply chain and farm gate pricing data, particularly given the growth in online platforms for farmers. Jablonski said that including behavioral components in models is important for ensuring that decision making is meaningfully integrated.

Jablonski said that the challenge in training students is balancing the trade-offs between depth and breadth. “I do not think anybody has figured out how to do this well,” she said, “but this is a topic we need to think through if we want to get the topics we are talking about today right.” Training students to be “T” thinkers (the vertical line is depth, and the horizontal line reflects their ability to communicate across silos) will be critical, she said, although she does not believe that pure interdisciplinary programs are the answer because students need depth in at least one area.

Jablonski’s last point was about the need to show the intended beneficiaries of a model the evidence used to power it and generate ideas that can improve the end user’s situation. It may be possible, she added, to use data scraping to provide data directly to U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), reduce farmers’ data-reporting requirements, and show the end users that ML is being used to support them.

MODERATED DISCUSSION

Sharon Kirkpatrick, discussion moderator, asked the panelists for their thoughts on where the field would be in 5–10 years and about too much optimism regarding future advances. Knight replied that it is easy to both overestimate what technology will do based on extrapolations of what is possible today and underestimate how profound the changed behavior and capabilities will be, particularly if the comparison is made to other exponentially expanding technologies, such as digital photography capability or AI. Regarding possibilities such as a personal device that can analyze an individual’s plate and provide them with dietary guidance, he thought that might even be possible now, but it has the ethical concern about what the device would tell the individual, how much predictive power it has, and how much of a difference the guidance would make. “The question is what can we really do [that] impact[s] health in a measurable way, has a large effect size, and is beneficial for the individual,” said Knight.

Sazonov, quoting Arthur C. Clarke, said “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” and that he believes AI may become magic given the breathtaking growth of the field in recent years. Given the speed of AI development, he said that it is hard to predict where the field will be in even a few years. Lamarche predicted that, unfortunately, phone apps

will tell the user what will happen if they eat a certain food but be based on unreliable data. “Someone will think about it and will invent it,” he said.

When asked how federal data collection protocols could be revamped to account for cutting-edge technologies, McRitchie called for more biospecimen collection, and Sazonov wished for more information about food composition and consumption patterns. For microbiome research, Knight said that it is important to have access to original biospecimens to repeatedly analyze them with newer and better methods. He also would like to have a better understanding of how to deal with privacy issues involving reidentification associated with DNA sequencing.

Lamarche asked the panelists if they see the risk of these sophisticated analyses increasing socioeconomic disparities in health, given cost and health literacy concerns. Sazonov said that technology accessibility improves with each generation, citing that many public health interventions are designed around cell phone technology that has spread around the world. Kirkpatrick said that the struggle is whether investments should go toward developing these technologies or to addressing the social determinants of health, such as affordable housing and an affordable healthy food supply.

Knight commented that an effective method of being equitable will be to integrate analytical methods with devices people will purchase and have with them anyway, such as a cell phone camera. He also said that to mitigate disparities, it is important to design technology to avoid financial or cultural barriers. He noted that the Study of Latinos project is collecting microbiome and metabolic data and reaching out to that underrepresented demographic. Other similar projects take the All of Us approach to diversity, but he called for complementing that approach with studies that contact particular populations with community representatives and investigating cultural factors that can be barriers to access. McRitchie said that it will be important to work with community leaders and others who serve vulnerable populations.

A participant asked if measurement error in metabolome and microbiome assays is negligible enough that AI-generated results will be more robust than they would be with imaging data. Knight said that different analytical methods for reading the microbiome have provided markedly different results, making cross-validation and assay standardization important, but funding for standardization and quality control efforts has been limited. Microbiome assays are getting better at reproducibility regarding repeated readouts from the same biospecimen, but problems remain with things such as misalignment of readouts. He also noted the challenge of comparing data generated by different analytical methods. McRitchie said that one of the big challenges with metabolomics is that many of the metabolites seen in spectral data are unknown. Characterizing those unknowns is important because then it will be possible to develop targeted assays that provide

actual concentrations as opposed to the relative amounts obtained from untargeted data.

Rodolphe Barrangou asked about a future in which models use individual genetic data and, if so, how dealing with personalized and private information will be handled. Holly Nicastro, program director in the NIH Office of Nutrition Research and program coordinator for NPH, powered by the All of Us research program, said that genomics will play a role in NPH, but it is unclear if individual genes or genetic markers will be predictors. “I think it would be naive to think that there would not be information to be gleaned from certain aspects of the genome and how a patient might want to eat to improve their health,” said Nicastro.

Kirkpatrick asked the panelists for advice for investigators who are starting to integrate AI and data science. Knight noted the room for responsible, far-reaching technology development that encourages people to try things and discover what is possible without too many preconceived notions while having safeguards for how the results will be applied clinically. “I would say take a two-pronged approach where, on the one hand, you do not want to inhibit researchers’ and especially students’ creativity in trying out new and untested methods on big data, but at the same time, you want to teach them on well-understood and well-established datasets what the guardrails are for drawing correct versus incorrect conclusions,” said Knight.

McRitchie suggested developing tutorials written in accessible language that identify limitations of the different methods, how to properly use a method, and how big a sample is necessary. Nicastro reiterated the importance of having study participants as partners involved in the study design and the questions they would like answered.

Barrangou commented that several speakers noted the gap between nutrition scientists and data scientists, but after listening to the presentations, he believes the relevant analogy is a mosaic. “Within nutrition, we have researchers, clinicians, food scientists, and many different kinds of sciences and disciplines, and on the AI side, we have engineers, mathematicians, data scientists, programmers, and statisticians,” he said. He asked the panelists for their thoughts on what the mosaic is missing most and how to fill these gaps. Das replied that addressing the scope of AI and ML projects requires a multidisciplinary approach involving all research areas and creating a transdisciplinary approach requires awareness and the resources to support it.

Regarding data availability, Dugundji noted that USDA has dashboards showing how long trucks are waiting at different places and that the U.S. Department of Transportation convened a group of private sector parties representing different links in the supply chain to map out the data needed from each link to improve the efficiency of each step. The beneficiaries of

this effort have been cargo ship owners, but she hoped the focus would include food.

Regarding training, Dugundji said that it is important that every student coming through her program graduates knowing how to program and have a basic understanding of these models so they can engage as managers of teams they may be supporting. Smith said that his institute’s leadership worked hard to bring together engineers and computer scientists with domain experts for specific projects. For example, staff members are using ML tools to help researchers involved in seed development build traits in crops that will lead to tastier food, improve supply chains, and map the connections between food, micronutrients, and human health. This approach, Smith said, seems to work well, although the biggest gap is in how human behavior affects what people eat.

Mejía-Argueta agreed with these comments and added that missing pieces include strategies to be more collaborative and, from the country perspective, understand the scenario planning needed to create better and more resilient supply chains. He noted that the Netherlands creates working groups with representatives from the private sector, nonprofit organizations, government, and academia who try to understand how to prepare for future challenges in different areas. “Perhaps that is something that we should start doing, because at the end, that is probably one of the ways in which we can boost the use of all the knowledge that we have,” said Mejía-Argueta. For him, one of the biggest challenges is to create the proper environment to start collaborating with each other so each collaborator gets the best of the available knowledge, awareness, techniques, and data.

Regarding how to get researchers to understand the value of moving out of their silos and be willing to share data and even work together before starting a project to increase data usability, Jablonski said that the first step is to ensure that data are generated more usably for a broader group of researchers across departments and agencies. When she conducts trainings for a variety of groups, she usually hears about the data her audience intends to collect, but they do not start with what is already available and which gaps exist. “If we do not start by understanding the data, we are going to continue to oversurvey groups and see declining response rates because groups do not see that the data they already provided are being used,” she said. She noted that in response to 9/11, the federal government collected a great deal of information about the supply chain but did not make those data available across federal agencies.

Smith agreed that a great deal of data, particularly at the federal level, is hard to access. For example, USDA has data on today’s price of spinach in St. Louis, but it is difficult to see how it has varied over time because those data are not stored, displayed, or made easily accessible. With his students, he has tried to build a resource catalog that lists where to find

various datasets, but even that is a challenge. He noted that USDA is trying to break down silos between different parts of the department to improve data access.

According to Smith, researchers have become more willing to be transparent about their data, which is important for replicability and having trust in research products. Accessing data from private entities, including farmers and consumers, continues to be a challenge because of issues of ownership and who will profit from the information they provide. He wondered about a way to construct data agreements so that the provider benefits and the data become more accessible for projects that would improve societal outcomes.