The Current Status and Future Direction of High-Magnetic-Field Science and Technology in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 1 Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopies

1

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopies

INTRODUCTION TO MAGNETIC RESONANCE

Magnetic resonance (MR) techniques have an extremely broad range of applications, including fundamental studies of novel materials in electronic, communications, and energy-related industries, as well as both fundamental and practical studies of disease-related biological molecules, and pharmaceuticals. MR techniques are nondestructive and noninvasive, and provide unique insights at the atomic, molecular, and meso-scales that can be monitored in situ, ex situ, or in operando, regardless of whether the system is structurally ordered or not.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is particularly useful to characterize the structural and dynamical attributes of complex biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and their complexes and aggregates. NMR is a critical characterization tool at every university with a strong research base, as well as many primarily undergraduate institutions (PUIs) and major chemical and biotech companies. Almost no product arising from a chemical synthesis or newly isolated natural product is established today without molecular elucidation by NMR. Furthermore, NMR is inherently quantitative and can provide relative and/or absolute quantitation across all components of multi-component targets precisely, accurately, and without perturbing the sample integrity or quality.

Thirteen Nobel Prizes have been awarded in areas directly related to or supporting the development of MR.1 The broad impact of MR techniques, together

___________________

1 C. Boesch, 2004, “Nobel Prizes for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance: 2003 and Historical Perspectives,” Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 20(2):177–179, https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.20120.

with the dependence of MR and especially NMR on high magnetic fields, makes achieving such fields a crucial component of progress in many areas of science and engineering, as highlighted in Box 1-1. The United States is currently falling behind research communities in Europe as access to high magnetic fields is extremely limited, with very few instruments in the United States, and without funding support and better managed helium resources, many NMR laboratories have been closed. As noted to the members of the committee, this includes university laboratories at the University of Illinois, Indiana University, the University of Michigan, Stanford University, the University of Utah, the University of Iowa, the University of Kansas, the University of Pennsylvania, and the State University of New York at Stony Brook. This list is not complete and does not include the many small teaching colleges and universities.

However, the drive for ever higher magnetic field strengths has been the rationale underpinning both research and commercial efforts in NMR for more

BOX 1-1

Highlights of Chapter 1

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is one of the most impactful tools available to researchers in chemistry, engineering, biomedical fields, and materials science. The capabilities of NMR continue to expand with the development of new experimental methods and new data analysis approaches and with the exploration of applications to new classes of scientific problems. NMR benefits from increasingly large magnetic fields that provide higher resolution and higher sensitivity. In the past decade, NMR instruments with ultrahigh-field magnets (>23.5 T, corresponding to >1.0 GHz 1H NMR frequencies) have been developed but have been installed primarily outside the United States. As predicted in the 2013 National Research Council report High Magnetic Field Science and Its Application in the United States: Current Status and Future Directions, insufficient investment by federal agencies in NMR instrumentation has resulted in a clear loss of U.S. leadership in NMR-based research.

Highlights

- Although at least 14 1.2 GHz NMR instruments have been installed or ordered worldwide to date, only one of these instruments exists in the United States. Insufficient support from federal agencies has produced a diminished role for U.S. laboratories in NMR-based research.

- For the United States to compete internationally in ultrahigh-field NMR, mechanisms for supporting cutting-edge research in this area need to adapt in order to cover the cost of instrumentation, technical experts, and long-term maintenance.

- Sources of funding earmarked for “moonshot” efforts are critically and additionally required to restore U.S. leadership.

- As high- and ultrahigh-field NMR magnets require liquid helium to maintain superconductivity at cryogenic temperatures, uncertainties in helium supply represent a major ongoing risk to research. U.S. laboratories need both a secure helium supply and funds for installation and operation of helium recycling systems.

than 50 years. The main challenges faced by NMR have been, and continue to be, sensitivity and resolution. NMR sensitivity (defined as the detection limit in terms of the minimum number of NMR-active spins to produce a signal) and resolution (the ability to discriminate two signals) both increase nonlinearly with field, effects that follow from multiplicative contributions from increased polarization and increased (resonance) frequency for detection, as well as from the spreading of the resonances in multidimensional spectral spaces. In the important case of half-integer, quadrupolar, solid-state NMR experiments, even greater gains from increasing field strengths (scaling ~field3/2) are obtained where higher-order effects scale inversely proportional to field, leading to sharper, more intense, signals. Consequently, higher magnetic fields have beneficial impacts in analytical NMR, including organic, natural products, and pharmaceutical applications, and have opened a plethora of new opportunities in the research of advanced materials including glasses, catalysts, metal organic frameworks (MOFs), and energy-related systems.

Nonlinear improvements in sensitivity and resolution are also imparted by ultrahigh fields (defined as fields greater than 23.5 T) on 1H-based solid-state NMR experiments. In both directly and indirectly detected 1H NMR experiments, the quenching of homonuclear dipolar interactions by the field, and by rotors capable of performing magic-angle-spinning (MAS) at rates in excess of 100 kHz, are proving to be game-changers in biomolecular applications. Comparable benefits are provided by ultrahigh fields in the NMR of biophysical multidimensional NMR experiments, where spectral resolution and improved sensitivity allow more detailed information to be obtained—on biomolecules, cellular machines, and in cell systems—on molecules and complexes of ever-growing complexity.

Driven by field-dependent gains in information, resolution, and sensitivity, field strengths in NMR have increased steadily since the 1960s. This is not trivial, because magnets for most applications of NMR in chemistry, materials science, and biology must have extraordinary stability and homogeneity—sometimes better than one part per billion. For several decades, the cutting edge of low-temperature superconductor (LTS) technology limited NMR measurements to approximately 21 T (equivalent to a 1H resonance frequency of 900 MHz). Relatively recent developments in high-Tc superconducting (HTS) wires have enabled higher fields to be reached. In the past decade, NMR systems based on 28.2 T magnets (1.2 GHz 1H NMR frequency) have become commercially available from the Bruker Corporation and have been installed at multiple sites. The overwhelming majority of these so-called “GHz-class systems” are located outside the United States.

In addition to their importance in NMR, high fields play important roles in other resonance-related experiments. No contemporary scientist or clinician requires reminding about the importance of magnetic fields in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In the clinic, MRI is uniquely able to localize the position and

properties of water molecules throughout tissues, giving radiologists essential, noninvasive visualization about the onset of diseases and the progress of treatment. Likewise, higher fields have opened entirely new horizons in understanding brain function and degeneration, as well as on basic biological research. Chapter 2 explains the consequences of and needs for higher fields in the United States for MRI purposes.

Physicists dealing with electron spin centers in biophysics, materials science, and quantum information also rely on high fields to perform electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) experiments. Compared to NMR, high-field EPR faces limitations in the availability of its ancillary equipment—including microwave terahertz radiation technology, cryogenics, and quasi-optics, which are often equally or more problematic than magnet availability. Still, terahertz-class EPR experiments done both at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL) and elsewhere have demonstrated the unique applications that high-field EPR can open in spintronics, magnonics, catalysis, waste remediation, and other matters of national importance.

Ion cyclotron resonance (ICR) is another important analytical technique that depends on high magnetic fields. ICR measurements at high fields are used to determine molecular masses with the highest available mass resolution. The 21 T facilities at NHMFL and Batelle have resolution of 1.6 × 106 (at m/z 400), root-mean-square mass measurement accuracy below 100 ppb, and the ability to resolve molecular features with m/z differences as small as 1.79 mDa.2 Users at NHMFL ICR have shown that these ultrahigh fields allow extremely complex mixtures to be analyzed, including multiple previously unknown proteoforms associated to in vivo post-translational modifications, petroleum mixtures,3 plastics degradation in the environment,4 and environmentally persistent polyfluoralkyl substances (PFASs).

Finding: High magnetic fields have a pervasive impact on research in chemical, biological, and physical sciences through resonance spectroscopies, including NMR, MRI, MRS, EPR, and ICR. These techniques are broadly applicable to molecules and materials of central importance to many areas of technology,

___________________

2 A.P. Bowman, G.T. Blakney, C.L. Hendrickson, S.R. Ellis, R.M.A. Heeren, and D.F. Smith, 2020, “Ultra-High Mass Resolving Power, Mass Accuracy, and Dynamic Range MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging by 21-T FT-ICR MS,” Analytical Chemistry 92(4):3133–3142, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04768.

3 M.L. Chacón-Patiño, M.R. Gray, C. Rüger, et al., 2021, “Lessons Learned from a Decade-Long Assessment of Asphaltenes by Ultrahigh-Resolution Mass Spectrometry and Implications for Complex Mixture Analysis,” Energy & Fuels 35(20):16335–16376, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c02107.

4 A.N. Walsh, C.M. Reddy, S.F. Niles, A.M. McKenna, C.M. Hansel, and C.P. Ward, 2021, “Plastic Formulation Is an Emerging Control of Its Photochemical Fate in the Ocean,” Environmental Science & Technology 55(18):12383–12392, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c02272.

as well as the pharmaceutical industries, agricultural industries, and health care. Higher magnetic fields generally enhance the sensitivity, resolution, and information content of resonance spectroscopy data.

ROLE OF NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE IN BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES

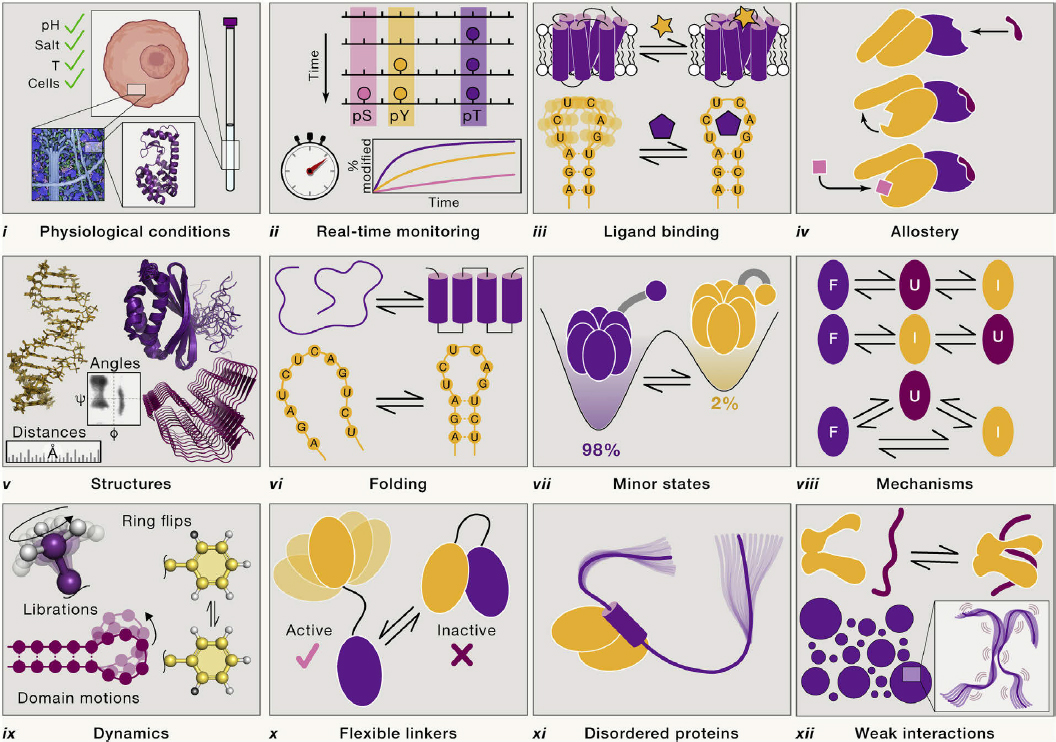

In biological sciences, NMR is one of the three principal methods for experimentally determining complete three-dimensional (3D) structures of biological macromolecules and complexes, along with X-ray crystallography and cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM). NMR also has a uniquely important role as the primary method for detailed characterizations of interactions among biological molecules, molecular motions and dynamics, and conformational properties of unstructured or partially structured regions of macromolecules. The past decade has also seen the development of new techniques that expand the power of NMR as a probe of the properties of biological molecules within cells and tissues, as shown in Figure 1-1, furthering the impactful applications of NMR to new biological problems.

Recent breakthroughs in technology and image analysis capabilities have enabled atomic-resolution structures of large biomolecular complexes to be solved by cryo-EM, which had been impossible a decade ago. The rapid expansion of cryo-EM in recent years has attracted considerable attention and resources, in some cases at the expense of biological NMR. It is therefore appropriate to summarize the relative strengths of the two classes of measurements.

The main strength of cryo-EM is in purely structural characterizations of the most highly ordered portions of large biomolecular complexes or assemblies. Cryo-EM methods are applied most successfully to systems that are homogeneous in size, composition, and structure. Although multiple coexisting structures can be analyzed successfully by cryo-EM in some cases, this generally depends on having samples in which the structural variations are discrete (rather than continuous) and samples in which the individual structural entities are well separated from one another.

Relative to cryo-EM, NMR has distinct roles and capabilities in studies of biomolecular systems. While NMR methods can also be used to determine atomic-resolution 3D structures, NMR methods uniquely provide a wealth of information about properties that are not accessible to cryo-EM or other techniques. These include information about site-specific molecular motions, conformational distributions of intrinsically disordered systems and disordered regions of partially ordered systems, and weak or transient intermolecular interactions that are central

SOURCE: Reprinted from T. Reid Alderson and L.E. Kay, 2021, “NMR Spectroscopy Captures the Essential Role of Dynamics in Regulating Biomolecular Function,” Cell 184(3):577–595, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.034. Copyright 2021 with permission from Elsevier.

to biological function.5 NMR methods can be used to define full mechanistic and kinetic pathways for processes such as structural conversions and the formation of oligomeric complexes.6 For example, they have proved crucial in unravelling the kinetic roles that keto-enolic and amino-imino tautomeric interconversions play in enriching the functional biology of nucleobases and in switching among canonical Watson-Crick and noncanonical DNA and RNA forms.7 NMR methods have also contributed to a molecular-level understanding of liquid-liquid phase separation phenomena of protein and nucleic acids, including the characterization of these biomolecular condensates,8 as well as opened the so-called four-dimensional (4D) structural functional dynamics associated by in-cell post-translational modifications.9 Recent experiments demonstrate that NMR can elucidate nonequilibrium, unidirectional structural conversion processes with millisecond time resolution,10 revealing dynamic and mechanistic phenomena that are well beyond the current capabilities of cryo-EM methods (or other experimental approaches).

Other recent examples of studies that demonstrate the unique information available from NMR measurements in a variety of biomolecular systems include the following:

- Understanding the protein-aided dynamics and transferring of water through biological membranes by 17O NMR.11

___________________

5 A.C. Murthy and N.L. Fawzi, 2020, “The (Un)structural Biology of Biomolecular Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation Using NMR Spectroscopy,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 295(8):2375–2384, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.REV119.009847; H.J. Dyson and P.E. Wright, 2021, “NMR Illuminates Intrinsic Disorder,” Current Opinion in Structural Biology 70:44–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2021.03.015.

6 R. Roy, A. Geng, H. Shi, et al., 2023, “Kinetic Resolution of the Atomic 3D Structures Formed by Ground and Excited Conformational States in an RNA Dynamic Ensemble,” Journal of the American Chemical Society 145(42):22964–22978; A. Ceccon, V. Tugarinov, F. Torricella, and G.M. Clore, 2022, “Quantitative NMR Analysis of the Kinetics of Prenucleation Oligomerization and Aggregation of Pathogenic Huntingtin Exon-1 Protein,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(29):e2207690119.

7 A. Rangadurai, E.S. Szymaski, I.J. Kimsey, H. Shi, and H.M. Al-Hashimi, 2019, “Characterizing Micro-to-Millisecond Chemical Exchange in Nucleic Acids Using Off-Resonance R1ρ Relaxation Dispersion,” Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 112:55–102.

8 A.C. Murthy and N.L. Fawzi, 2020, “The (Un)structural Biology of Biomolecular Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation Using NMR Spectroscopy,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 295(8):2375–2384, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.REV119.009847.

9 F.-X. Theillet, C. Smet-Nocca, S. Liokatis, et al., 2012, “Cell Signaling, Post-Translational Protein Modifications and NMR Spectroscopy,” Journal of Biomolecular NMR 54:217–236.

10 J. Jeon, C.B. Wilson, W.-M. Yau, K.R. Thurber, and R. Tycko, 2022, “Time-Resolved Solid State NMR of Biomolecular Processes with Millisecond Time Resolution,” Journal of Magnetic Resonance 342:107285.

11 J. Paulino, M. Yi, I. Hung, et al., 2020, “Functional Stability of Water Wire–Carbonyl Interactions in an Ion Channel,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(22):11908–11915.

- Engineering dynamic properties to endow proteins with functions that do not derive from their most stable conformational structure.12

- Describing how multiple conformational kinase states give rise to multiple intrinsic regulatory mechanisms, thereby explaining how oncogenic mutants can counteract inhibitory mechanisms and shedding light on designing drugs to bypass drug resistance.13

- Understanding how the interplay between molecular tautomerism, conformational changes, and multiple coexisting structures modulate gene regulation, protein binding, and post-transcriptional modifications in RNA.14

- Demonstrating the correlation arising between liquid-liquid phase separation phenomena and pathogenic protein aggregation.15

- Elucidation of structural and dynamical properties of HIV-1 and SARS CoV-2 proteins that are essential for viral infectivity.16

Finding: Advances in cryo-EM and artificial intelligence (AI)-based structural prediction have created an impression in the minds of some university administrators and funding agency personnel that biological NMR has been “superseded.” This impression is false. In fact, as applied to biomolecular systems, AI-based structure prediction, cryo-EM, and NMR are largely complementary. NMR continues to be a crucial experimental tool for biology, biochemistry, and biophysics, with continually expanding capabilities. Role of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in physical and materials sciences.

NMR, especially in the solid state, was recognized as far back as the 1970s as a characterization tool that would transform entire industries. Beginning especially

___________________

12 E. Rennella, D.D. Sahtoe, D. Baker, and L.E. Kay, 2023, “Exploiting Conformational Dynamics to Modulate the Function of Designed Proteins,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(18):e2303149120.

13 T. Xie, T. Saleh, P. Rossi, and C.G. Kalodimos, 2020, “Conformational States Dynamically Populated by a Kinase Determine Its Function,” Science 370(6513):eabc2754.

14 L.R. Ganser, , M.L. Kelly, D. Herschlag, and H.M. Al-Hashimi, 2019, “The Roles of Structural Dynamics in the Cellular Functions of RNAs,” Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 20(8):474–489.

15 S. Ambadipudi, J. Biernat, D. Riedel, E. Mandelkow, and M. Zweckstetter, 2017, “Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation of the Microtubule-Binding Repeats of the Alzheimer-Related Protein Tau,” Nature Communications 8(1):275.

16 S. Gupta, J.M. Louis, and R. Tycko, 2020, “Effects of an HIV-1 Maturation Inhibitor on the Structure and Dynamics of CA-SP1 Junction Helices in Virus-Like Particles,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(19):10286–10293; M. Lu, R.W. Russell, A.J. Bryer, et al., 2020, “Atomic-Resolution Structure of HIV-1 Capsid Tubes by Magic-Angle Spinning NMR,” Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 27(9):863–869; J. Medeiros-Silva, A.J. Dregni, N.H. Somberg, P. Duan, and M. Hong, 2023, “Atomic Structure of the Open SARS-CoV-2 E Viroporin,” Science Advances 9(41):eadi9007.

with polymers and plastics—disordered solids that eluded other characterization tools—their structure and property relationships were critical for development. When synthetic chemists and chemical engineers formulated a new polymer, NMR provided the primary means to understand what was fabricated in their processes.

Following closely were expansions into many new materials—especially zeolites, glasses, cements, electrochemical materials (e.g., batteries), metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and geochemical species. These are almost exclusively disordered materials with specific laboratory-to-industry relevance.

New breakthroughs are provided by higher fields, enabling access to new atomic handles and “exotic” nuclei (i.e., 17O, 103Rh, 187Os, 189Os). Isotopes with NMR-active spins that are newly accessible at 28.2 T (1.2 GHz) are shown in the highlighted squares in Figure 1-2. Where 109Ag used to be at the former limit of detection for most instruments, additional isotopes can be probed. Other new and unique research becomes possible at high magnetic fields, pushing back the line of what is “impossible to see” today.

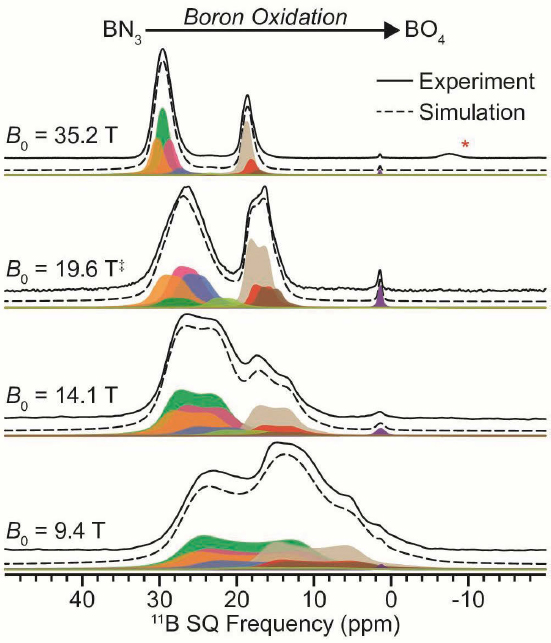

A particularly important benefit of ultrahigh magnetic fields arises in materials NMR measurements targeting half-integer quadrupolar nuclei—that is, nuclei with nuclear spin quantum numbers, I, of 3/2, 5/2, 7/2, and 9/2. These constitute ~70 percent of the NMR-active nuclei in the periodic table, and their easily accessed central +1/2 ↔ −1/2 transition have relatively narrow NMR patterns whose linewidths are proportional to the inverse of the external magnetic field, resulting in both sensitivity gains proportional to ~B05/2 and enhanced resolution with fields (Figure 1-3). This has allowed for unprecedented studies of elements important in biology, chemistry, and materials sciences, including 17O, 25Mg, 35Cl, 39K, 43Ca, 67Zn, 95Mo, and 99Ru (to list just a few of the accessible isotopes).

Higher magnetic fields and more extreme experimental conditions (of temperature and pressure ranges, including in the presence of other stimuli such as light, electrons, or external electric fields) are also leading to an increased focus on light ion dynamics, particularly in studies of batteries and related electrochemically relevant materials, and in understanding ionic conductors. The “insensitivity” of NMR (relative to optical methods) is becoming less and less of a barrier via dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP), enabling surface chemistry to be studied (and discriminated from “bulk” signals), and characterization of high-surface area species, especially nano- and carbon-capture materials.

The materials discussed above are all now routinely studied, with considerable efforts in NMR studies of electrochemical cell reactions in situ,17 of metal-organic

___________________

17 E.W. Zhao, T. Liu, E. Jónsson, et al., 2020, “In Situ NMR Metrology Reveals Reaction Mechanisms in Redox Flow Batteries,” Nature 579(7798):224–228, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2081-7.

NOTES: At 40 T, NMR of multiple elements shown in yellow would become routine, and elements shown in red would become accessible for the first time. The figure labels these as difficult elements, but the committee suggests these elements become new opportunities. As an example, structural and mechanistic studies of osmium-based catalysts would become possible. Elements with spin-1/2 isotopes are given as circles and are often regarded as the most routine isotopes. For a full description of isotopes that can be studied using NMR methods that includes the other isotopes and noble gases, see https://nmrfam.wisc.edu/solid-state-nmr-ssnmr.

SOURCE: Iowa State University, “Rossini Group: Research,” 2024, accessed July 24, 2024, https://rossini.chem.iastate.edu/research. Image courtesy of Rossini Group, Iowa State University and Ames National Laboratory.

NOTES: The spectrum collected at 35.2 T was measured at NHMFL. Asterisk (*) corresponds to spinning sidebands. Double dagger (‡) refers to the fact that relative 11B NMR peak intensities for the spectrum recorded at B0 = 19.6T is different from the spectra recorded at either 9.4 T, 14.1 T or 35.2 T. The difference in the peak intensities is due to the different peaks having different T2’ relaxation constants. The 11B spin echo recorded at B0 = 19.6T was recorded with an ca.1.5 ms total echo period, in which significant T2’ relaxation occurred.

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from R.W. Dorn, M.C. Cendejas, K. Chen, et al., 2020, “Structure Determination of Boron-Based Oxidative Dehydrogenation Heterogeneous Catalysts with Ultrahigh Field 35.2 T 11b Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy,” ACS Catalysis 10(23):13852–13866, https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.0c03762. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

frameworks and other gas sorbents,18 of heterogeneous catalysts and their activities,19 and optically active materials.20 In all these instances, NMR can probe the structure, dynamics, and electronic state of materials using NMR-active isotopes as probes.

Semiconducting materials are another area where NMR is playing a crucial role, because of intense interest in the interplay that structures and ion/group dynamics play in solar cells, in light-matter interactions, and in opportunities for new “quantum sensing” and quantum information materials. Perovskites have been an area of intense exploration, with NMR focusing on ion motion and degradation of materials over time.21 NMR can address these issues in both films and bulk materials, even when the latter studies are inaccessible from bulk diffraction methods. The role of dopants and even surfaces and interfaces in these systems can be investigated by NMR via sensitivity enhancement techniques, such as DNP. With the growing interest in “color centers” (e.g., nitrogen-vacancy [NV] centers) for quantum applications, NMR leads to new understanding of those changes that occur when doping, substituting, or modifying the surface of films and nanomaterials occurs.

Some recent examples of high-impact studies that demonstrate the unique information available from NMR measurements in technologically important materials systems include the following:

___________________

18 B.E.G. Lucier, S. Chen, and Y. Huang, 2018, “Characterization of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Unlocking the Potential of Solid-State NMR,” Accounts of Chemical Research 51(2):319–330, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00357.

19 R. Jabbour, M. Renom-Carrasco, K.W. Chan, et al., 2022, “Multiple Surface Site Three-Dimensional Structure Determination of a Supported Molecular Catalyst,” Journal of the American Chemical Society 144(23)10270–10281, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c01013.

20 M. Seifrid, G.N.M. Reddy, B.F. Chmelka, and G.C. Bazan, 2020, “Insight into the Structures and Dynamics of Organic Semiconductors Through Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy,” Nature Reviews Materials 5(12):910–930, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-020-00232-5.

21 D.J. Kubicki, D. Prochowicz, E. Salager, et al., 2020, “Local Structure and Dynamics in Methylammonium, Formamidinium, and Cesium Tin(II) Mixed-Halide Perovskites from 119Sn Solid-State NMR,” Journal of the American Chemical Society 142(17):7813–7826, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c00647.

22 W. Cai, R.D. Piner, F.J. Stadermann, et al., 2008, “Synthesis and Solid-State NMR Structural Characterization of 13C-Labeled Graphite Oxide,” Science 321(5897):1815–1817, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1162369.

23 D.J. Kubicki, S.D. Stranks, C.P. Grey, and L. Emsley, 2021, “NMR Spectroscopy Probes Micro-structure, Dynamics and Doping of Metal Halide Perovskites,” Nature Reviews Chemistry 5(9):624–645, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-021-00309-x.

- 207Pb,24 probing the role of the cation reorientation dynamics,25,26 composite stabilization in metal-organic hosts,27 and using 133Cs NMR to observe interface structures.28

- MOFs that are envisioned as host materials for catalysis, separations, and sorbent applications are extensively studied by gas-phase and solid-state NMR; because these materials are partially disordered, NMR is one of the primary tools for structural studies;29electrochemically active materials that undergo ion dynamics during charge and discharge cycles are an attractive target for NMR, including in situ and operando methods30 in studies of super-capacitors,31 and imaging techniques capable of elucidating the spatial distribution of both currents and of the chemical transformations undergone by the electrolytes.32

___________________

24 T.A.S. Doherty, S. Nagane, D.J. Kubicki, et al., 2021, “Stabilized Tilted-Octahedra Halide Perovskites Inhibit Local Formation of Performance-Limiting Phases,” Science 374(6575):1598–1605, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl4890.

25 J.-W. Lee, S. Tan, S.I. Seok, Y. Yang, and N.-G. Park, 2022, “Rethinking the A Cation in Halide Perovskites,” Science 375(6583):eabj1186, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj1186.

26 C.-C. Lin, S.-J. Huang, P.-H. Wu, et al., 2022, “Direct Investigation of the Reorientational Dynamics of A-site Cations in 2D Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Perovskite by Solid-State NMR,” Nature Communications 13(1):1513, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29207-6.

27 J. Hou, P. Chen, A. Shukla, et al., 2021, “Liquid-Phase Sintering of Lead Halide Perovskites and Metal-Organic Framework Glasses,” Science 374(6567):621–625, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf4460.

28 X. Li, W. Huang, A. Krajnc, et al., 2023, “Interfacial Alloying Between Lead Halide Perovskite Crystals and Hybrid Glasses,” Nature Communications 14(1):7612, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467023-43247-6.

29 X. Kong, H. Deng, F. Yan, et al., 2013, “Mapping of Functional Groups in Metal-Organic Frameworks,” Science 341(6148):882–885, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1238339.

30 D. Lyu, Y. Jin, P.C.M.M. Magusin, et al., 2023, “Operando NMR Electrochemical Gating Studies of Ion Dynamics in PEDOT:PSS,” Nature Materials 22(6):746–753, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-023-01524-1.

31 M. Deschamps, E. Gilbert, P. Azais, et al., 2013, “Exploring Electrolyte Organization in Supercapacitor Electrodes with Solid-State NMR,” Nature Materials 12(4):351–358, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3567.

32 M. Mohammadi, E.V. Silletta, A.J. Ilott, and A. Jerschow, 2019, “Diagnosing Current Distributions in Batteries with Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Journal of Magnetic Resonance 309:106601, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2019.106601; A.J. Ilott, M. Mohammadi, C.M. Schauerman, M.J. Ganter, and A. Jerschow, 2018, “Rechargeable Lithium-Ion Cell State of Charge and Defect Detection by In-Situ Inside-Out Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Nature Communications 9(1):1776, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04192-x.

- Glasses and intrinsically disordered materials benefit from solid-state NMR to probe local coordination environments, including structural transformations,33 including “glassy” MOFs (e.g., by 67Zn NMR).34

- Organic semiconductors, where site-specific dynamics and local structures can be measured by NMR.35

In nearly all these systems, NMR serves as a primary structural characterization tool that is used in conjunction with other vibrational and optical spectroscopies, as well as a tool providing dynamic and structure-function-materials performance metrics for electronically and catalytically active materials.

Finding: There are few measurement technologies that compete with NMR as a tool for the atomic-level characterization of disordered and dynamic solids. NMR is leading to critical insights about these materials that cannot be detected or quantified by other means. And higher magnetic fields are the next game-changing opportunity for the study of quadrupolar species such as 17O, 67Zn, and other low-sensitivity, quadrupole-broadened nuclei. Therefore, high magnetic fields are an enabling technology for advancing these structure-property studies.

ROLE OF NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE IN PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES

NMR’s experimentally unique and information-rich insights into molecular structures and dynamics at the atomic level provide critical information to diverse industries dealing with organic and pharmaceutical products in the United States. For the most part, while large companies shoulder the expenses (capital, facilities, maintenance, and staff) to resource NMR instrumentation and collect experimental data at fields of up to 14+ T (600 MHz for 1H), doing so can be prohibitively difficult for small- to mid-size companies. Alternatives include academic collaborations or finding fee-for-service options through universities or contract research organizations.

___________________

33 T. Edwards, T. Endo, J.H. Walton, and S. Sen, 2014, “Observation of the Transition State for Pressure-Induced BO3-BO4 Conversion in Glass,” Science 345(6200):1027–1029, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1256224.

34 R.S.K. Madsen, A. Qiao, J. Sen, et al., 2020, “Ultrahigh-Field 67Zn NMR Reveals Short-Range Disorder in Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework Glasses,” Science 367(6485):1473–1476, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz0251.

35 M. Seifrid, G.N.M. Reddy, B.F. Chmelka, and G.C. Bazan, 2020, “Insight into the Structures and Dynamics of Organic Semiconductors Through Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy,” Nature Reviews Materials 5(12):910–930, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-020-00232-5.

The importance of NMR in industry is documented in several annual conference programs, including meeting archives of SMASH (a scientific meeting highlighting Small Molecule NMR research and applications) and Practical Applications in NMR in Industry Conference (PANIC).36 As a use case of NMR in pharmaceuticals, consider that in chemical R&D, an NMR spectrum is routinely required to be documented in a chemist’s notebook. The NMR data act as “molecular fingerprints” for proof of synthesis and are an integral part of patent writing and later publications. However, NMR spectroscopy contributes experimental data even more broadly, across the pharmaceutical pipeline and across functions. Specific examples include the following: hit identification screening of compound and fragment libraries for binding targets; investigation of salt forms, encapsulations, crystallinity, amorphous stability, solid polymorphs, and solubilization characteristics across different solvent mixtures for drug formulations; biophysical characterization of targets, free ligands, or protein complexes, providing orthogonal experimental observations to complement information from crystallography, cryo-EM, and hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX); drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics queries such as quantitative and structural information on metabolites; and drug design to test hypotheses around enhanced structure-based drug design and intrinsic dynamics.

Universal challenges to the state of NMR research apply also in the industry sector; these include experimental resolution and sensitivity; accessibility, affordability, and availability of instrumentation; and trained scientists. That training encompasses technical and scientific know-how to correctly interpret spectral results, understand which experiments to run, and maintain the instruments to perform optimally. Unique concerns for industry that can distinguish its users include guarding intellectual property, aggressive timelines for relevancy from inception of experiment to go or no-go decisions on next steps, and access to fee-for-service at higher fields. For small- to mid-size companies, improved fee-for-service access to solids NMR, nonstandard experiments, variable temperature work, and field strengths above 400 MHz (9.4 T) can be particularly challenging. Currently, with ~$20 million price tags, the private sector cannot justify return on investment for ultrahigh-field NMR spectrometers.

Finding: Ultrahigh-field NMR in the United States has not yet become available for industry, given limited public (user-facility) resources and prohibitive price ranges for the equipment. This limits synthetic and natural product efforts, as well as the characterization of polymorphic forms and solid-phase interactions in pharmaceutical formulations.

___________________

36 Practical Applications of NMR in Industry Conference 2023 “Past Program Guides,” https://panicnmr.com/past-program-guides. https://smashnmr.org/previous-conferences.

The U.S. chemical industry would benefit from nationally supported user facilities that provide suitable options for conducting special NMR investigations. A robust infrastructure for academic-industry collaborations to address questions of industrial relevance (i.e., filling gaps in fundamental understandings in the short-term, with unknown longer-term benefits) could routinely benefit from ultrahigh magnetic fields for NMR studies. Such “blue-sky” pharma-oriented experiments could include the following: (1) natural abundance protein-observed high-resolution NMR, as isotopically labeled constructs are generally difficult to obtain; (2) advanced solution-state NMR dynamic studies, providing complementary insights about cryptic pockets, allosteric binding, and multi-protein complexes; (3) NMR studies on multi-component protein complexes, where one component is isotopically labeled; (4) in-cell NMR studies of drug-protein binding; and (5) characterization of lipid nanoparticles for drug and RNA delivery, including DNP-enhanced studies.37

An alternative use of ultrahigh fields is the higher sensitivity that this provides, enabling factor for both faster acquisitions and higher throughput. This could help detect lower concentrations and could enable the routine acquisition of spectral data from 17O at natural abundance, in addition to the 1H, 13C, and 15N experiments that are normally done. These nuclei are viewed as particularly relevant as data to feed into AI and machine learning training sets for discerning trends in chemical reactivity, pKa, and intramolecular hydrogen bonding. Databases for insights relating NMR experimental parameters (shifts, J-couplings, through-space proximities, and dynamics) to ligand potency, selectivity, and permeability would be impactful, as well as formulations trends across preferred crystal forms across solvents and salts.

Finding: Ultrahigh-field NMR could provide the drug-discovery industry with new opportunities that are currently unavailable to all but the most specialized research laboratories.

Regarding Key Recommendation 3 (see Summary), the installation of new NMR spectrometers with 1H NMR frequencies in the 1.0–1.2 GHz range is motivated primarily by the needs of the basic research community in the United States. This recommendation may also benefit research and development efforts in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

___________________

37 J. Viger-Gravel, A. Schantz, A.C. Pinon, A.J. Rossini, S. Schantz, and L. Emsley, 2018, “Structure of Lipid Nanoparticles Containing siRNA or mRNA by Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 122(7):2073–2081.

KEY TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS DURING THE PAST DECADE

Non-Commercial Magnets

Over the past decade, several developments have revolutionized ultrahigh-field NMR. One was the advent of magnets crossing the gigahertz barrier. This revolution started in 2017 with the commissioning by NHMFL of the 36 T series-connected hybrid magnet (36 T SCH), a system that enabled, from 2018 onward, the acquisition of solid-state NMR spectra at 1.5 GHz 1H Larmor frequencies. By combining an LTS-based superconducting outsert with a nonsuperconducting Bitter magnet insert, the SCH magnet exhibits approximately 0.1 ppm stability and homogeneity, compatible with many applications of solid-state NMR.38 This arrangement provided an unprecedented field/stability combination which serves the NMR, EPR, and condensed matter physics (CMP) communities, even if the system still requires 12 MW of power for maximum field operation.

The value of the SCH system at NHMFL is amply illustrated by multiple publications since 2018, targeting “difficult” nuclei such as 17O, 25Mg, 35Cl, 39K, 43Ca, 67Zn, and 95Mo (i.e., nuclei that were previously thought to be beyond the reach of NMR methods owing to their large quadrupolar couplings, low gyromagnetic ratios, or low abundance). Examples include recent studies of boron oxide catalysts,39 molybdenum disulfide nanostructures,40 and fatty-acid-based materials.41

In 2017, NHMFL also commissioned an all-superconducting LTS/HTS 32 T system. Although designed for cryogenic condensed matter physics experiments, this magnet demonstrated approximately 20 ppm homogeneity and better temporal stability than even the SCH counterpart, offering a platform for wideline NMR experiments of interest in materials applications. These U.S.-based landmarks, coupled to promising developments of a 40 T successor to the 32 T all-superconducting

___________________

38 Z. Gan, H. Ivan, X. Wang, et al., 2017, “NMR Spectroscopy Up to 35.2T Using a Series-Connected Hybrid Magnet,” Journal of Magnetic Resonance 284:125–136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2017.08.007.

39 R.W. Dorn, L.O. Mark, I. Hung, et al., 2022, “An Atomistic Picture of Boron Oxide Catalysts for Oxidative Dehydrogenation Revealed by Ultrahigh Field 11B–17O Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy,” Journal of the American Chemical Society 144(41):18766–18771, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c08237.

40 H.J. Jakobsen, H.Bildsøe, M. Bondesgaard, et al., 2021, “Exciting Opportunities for Solid-State 95Mo NMR Studies of MoS2 Nanostructures in Materials Research from a Low to an Ultrahigh Magnetic Field (35.2 T),” The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 125(14):7824–7838, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c10522.

41 J. Špačková, C. Fabra, S. Mittelette, et al., 2020. “Unveiling the Structure and Reactivity of Fatty-Acid Based (Nano)materials Thanks to Efficient and Scalable 17O and 18O-Isotopic Labeling Schemes.” Journal of the American Chemical Society 142(50):21068–21081. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c09383.

system being conducted at NHMFL,42 bode well for the routine execution of NMR in excess of 1.8 GHz. Based on NHMFL’s experience in building a 36 T NMR SCH magnet and a 32 T all-superconducting physics magnet, and of the ongoing efforts to construct a 40 T all-superconducting physics magnet, the construction of a 40 T all-superconducting magnet with sufficient homogeneity and stability for NMR studies of solid materials seems to be within reach in the coming decade. This report therefore recommends funding the construction of an all-superconducting 40 T NMR magnet with approximately 1 ppm homogeneity and stability better than 1 ppm. This NMR magnet would be aimed specifically at applications to quadrupolar nuclei in solid materials. In addition, the underlying technological developments required for this magnet will lower the barrier to subsequent commercialization.

Finding: Noncommercial instrumentation, such as the 1.5 GHz SCH magnet at NHMFL, is highly advantageous for certain applications of NMR, especially in studies of materials and elements with quadrupolar nuclei. The availability of this instrumentation is highly beneficial for certain areas of research in the United States. However, this single research instrument does not fully compensate for the ubiquitous need for high-end commercial instrumentation.

Developments in Commercial High-Field NMR Magnets

NMR-quality magnets with fields up to 28.2 T (1.2 GHz 1H NMR frequency) were under development when the 2013 NRC report was written more than 10 years ago. It is notable that several 1.2 GHz NMR systems had been ordered in Europe but had not yet been installed at the time of that report. Since 2020, 1.2 GHz NMR instruments have been made commercially available by Bruker Biospin, and at least 12 of these instruments have been ordered for or installed in European laboratories. Currently, only one 1.2 GHz NMR instrument has been delivered in the United States—a spectrometer at The Ohio State University, purchased with funds from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Two 1.1 GHz instruments have been or will soon be installed in the United States, again with funds from NSF, and one 1.1 GHz instrument has been purchased with funding from private sources. These magnets incorporate LTS and HTS technologies that also have applications for making compact, lower-field instruments. It is clear from these developments that the revolution that HTS materials can bring into the field of NMR has only just begun.

___________________

42 National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 2022, “40-Tesla Superconducting Magnet,” https://nationalmaglab.org/magnet-development/magnet-projects/40-tesla-superconducting-magnet.

Finding: The introduction of LTS and HTS all-superconducting magnets with parts-per-billion stability and homogeneity has revolutionized the field of NMR. The majority of these commercially available, ultrahigh-field NMR instruments are found outside of the United States.

Dynamic Nuclear Polarization

Recent technological advances in ancillary methods have also had an impact on ultrahigh-field NMR experiments. Foremost among these has been the extension of dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) techniques for solid-state NMR research to higher fields.43 DNP technologies dramatically improve the sensitivity of solid-state NMR experiments by transferring spin polarization from electrons to nuclei, typically producing signal enhancements of two orders of magnitude. This allows explorations of surfaces and interfaces inaccessible to conventional NMR methods44 and allows NMR measurements on small quantities or dilute solutions of biomolecular systems.45,46 Extension of DNP to higher fields depends on the development of high-power, high-frequency microwave sources to drive electron spin transitions (~526 GHz at 18.8 T), as well as the development of suitable paramagnetic additives.47 Substantial progress has been made in both areas, through a combination of efforts in academia and industry. The combination of DNP with neutron scattering techniques provides a powerful means of increasing the sensitivity of the method. For example, DNP can increase scattering intensities in neutron diffraction of biological crystals by factors of 10–10048 (see Chapter 10 for details).

Roughly 55 commercial DNP instruments have been installed worldwide for materials and biophysical research since 2010. Of these, only 9 are in the United

___________________

43 K. Jaudzems, A. Bertarello, S.R. Chaudhari, et al., 2018, “Dynamic Nuclear Polarization-Enhanced Biomolecular NMR Spectroscopy at High Magnetic Field with Fast Magic-Angle Spinning,” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 57(25):7458–7462, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201801016.

44 A. Mishra, M.A. Hope, M. Almalki, et al., 2022, “Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Enables NMR of Surface Passivating Agents on Hybrid Perovskite Thin Films,” Journal of the American Chemical Society 144(33):15175–15184, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c05316.

45 D.W. Conroy, Y. Xu, H. Shi, et al., 2022, “Probing Watson-Crick and Hoogsteen Base Pairing in Duplex DNA Using Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(30):e2200681119, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200681119.

46 J. Jeon, W.-M. Yau, and R. Tycko, 2023, “Early Events in Amyloid-β Self-Assembly Probed by Time-Resolved Solid State NMR and Light Scattering,” Nature Communications 14(1):2964, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38494-6.

47 T. Halbritter, R. Harrabi, S. Paul, et al., 2023, “PyrroTriPol: A Semi-Rigid Trityl-Nitroxide for High Field Dynamic Nuclear Polarization,” Chemical Science 14(14):3852–3864, https://doi.org/10.1039/D2SC05880D.

48 H.B. Stuhrmann, 2023, “Polarised Neutron Scattering from Dynamic Polarised Nuclei 1972–2022,” The European Physical Journal E 46(6):41, https://doi.org/10.1140/epje/s10189-023-00295-6.

States. Of the ~25 commercial DNP instruments with fields of 14.1 T or higher, only ~4 are in the United States. NHMFL pays a crucial role in offsetting this deficit in commercial DNP instrumentation by providing widespread access to users (particularly new faculty users). As a result, roughly 40 percent of publications arising from all DNP NMR instruments with fields of 14.1 T or higher installed worldwide are based on data that were obtained with the one DNP NMR instrument at NHMFL.

Finding: DNP is an ancillary technology with fundamental importance for NMR, especially in studies of solids. The majority of commercial DNP NMR instruments, especially instruments with fields of 14.1 T and above, are found, once again, outside the United States.

High-Speed Magic-Angle Spinning and Advances in Data Analysis

Magic-angle spinning (MAS) is used almost universally in solid-state NMR to average out orientation-dependent spin interactions that would otherwise broaden the NMR lines severely. Again, through a combination of efforts in academia and industry, technology for MAS at speeds above 100 kHz (macroscopic sample rotation periods below 10 ms) has been developed. When combined with high magnetic fields, this results in 1H NMR linewidths and spectral resolution in solids that are comparable to those in solutions, enabling 1H-detected multidimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy of protein assemblies in nanomole quantities.49,50

NMR has been strongly affected by progress in automation, compressed data sensing, and AI-based processing and data interpretation. Together, these advances have resulted in dramatic improvements in the throughput of multidimensional NMR measurements, both for pharmaceutical processes as well as in high-field studies of proteins, protein complexes, and other large biological molecules.

Finding: Continuing progress in nuclear spin hyperpolarization methods, NMR probe technology, and methods for data acquisition and processing creates important synergies with ultrahigh-field magnet technology, further establishing NMR as one of the most powerful spectroscopic techniques available in the physical, chemical, and biological sciences.

___________________

49 M. Callon, D. Luder, A.A. Malär, et al., 2023, “High and Fast: NMR Protein–Proton Side-Chain Assignments at 160 kHz and 1.2 GHz,” Chemical Science 14(39):10824–10834, https://doi.org/10.1039/D3SC03539E.

50 T. Le Marchand, T. Schubeis, M. Bonaccorsi, et al., 2022, “1H-Detected Biomolecular NMR Under Fast Magic-Angle Spinning,” Chemical Reviews 122(10):9943–10018, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00918.

Status of Magnetic Resonance in the United States

“Worldwide competition is intense,” according to scientific leaders at NHMFL.51 Yet there is clear evidence that in the particular case of NMR, the United States has passed a tipping point, falling well behind other communities in its capabilities and funding for the high-field resources enabling research. Table S-1 and the summary chapter above illustrates this succinctly, given the paucity of high-field instruments in the United States relative to other countries worldwide.

Over the past decade or more, most high-field NMR instrumentation—both for solid and liquid samples—has been installed outside of the United States. About a dozen commercial 1.1 GHz and 1.2 GHz systems have been ordered or installed in Europe. The large majority of these are in large NMR user facilities with extensive infrastructure, service and staff personnel, and a track record of decades serving the European (and Asian) scientific communities. In contrast, only four such commercial systems have been ordered or installed in the United States, with only one of these in a facility with a track record of user-focused service (University of Wisconsin–Madison). U.S. researchers have only limited access to these user facilities, and both their long-term support and funding structures are still to be defined. The relative scarcity of resources in the United States is being offset—but only in part—by the NSF midscale instrumentation program and by the > 300 NMR users served annually by NHMFL. Neither NIH nor DOE have evidenced an interest in enhancing the ultrahigh-field NMR infrastructure to their scientific and industrial constituencies.

The 2013 NRC report predicted that a lack of investment in cutting-edge high-field NMR instrumentation would deprive the United States of a leadership position in all areas of science that depend on ultrahigh-field NMR. This prediction has now come to pass (see Table S-1). Aside from the unique facilities at NHMFL, ultrahigh-field NMR facilities in the entire United States are currently comparable to the NMR facilities in a few universities within countries with smaller materials and biomedical research communities, such as the United Kingdom or Switzerland.

Finding: For more than 10 years, support for high-field and ultrahigh-field NMR instrumentation in the United States has been consistently lower than support in advanced European and Asian facilities.

The low level of support for high-field and ultrahigh-field NMR instrumentation has had negative effects on U.S. science. In applications to fields that include structural biology, batteries and energy storage, and pharmaceutical sciences, the U.S. NMR community no longer has a leadership role. In the experiences of study

___________________

51 Tom Painter, NHMFL, “Introduction and Context,” presentation, August 17, 2023.

committee members, it has become increasingly rare for the best young scientists from Europe and Asia to come to the United States for graduate or postdoctoral research in NMR, simply because NMR facilities in the United States have fallen below the international standard.

Private and state U.S. flagship universities are increasingly deterred by the high costs of setting up and maintaining state-of-the-art NMR facilities and groups, thereby severely hurting the U.S. ability to train a new generation of students and postdocs knowledgeable in MR. Notably, such young scientists form the community of researchers and scientists who enter professions to staff NMR laboratories in the pharmaceutical industry and in chemical industries, who staff radiology laboratories and diagnostic laboratories in hospitals, who run NMR facilities at universities, and who teach about and develop new technologies in MRI imaging and NMR spectroscopy. As U.S. funding decreases, one might ask, who do funding agencies believe will fill those roles in the future? This trend is likely to accelerate even further in the coming years, leading to a magnified train of events that will deprive the chemical, pharmaceutical, and biomedical industrial and academic establishments from an irreplaceable know-how.

Conclusion: In the area of NMR spectroscopy, the United States has fallen behind other countries, particularly European countries, leading to a reliance on colleagues overseas to push the frontiers of high-field research. U.S. researchers must travel overseas for access, exporting talent and ideas in order to pursue these cutting-edge research themes, becoming dependent on international equipment for domestic research, and depriving new generations of trainees from the kind of research expertise available to their colleagues overseas.

Recent investments by NSF in two 1.1 GHz and one 1.2 GHz NMR spectrometers in the United States are a first step toward restoring the United States to a competitive level in this area of research, but this is not sufficient. These investments should have started a decade ago and would need to continue for an extended period of time to make up for the existing deficit. The committee estimates that a dozen additional ultrahigh-field NMR instruments, funded by federal agencies that include NIH, would be needed to bring U.S. laboratories to approximate parity with their international counterparts in terms of access to state-of-the-art instrumentation. Such an investment would also serve to reinvigorate NMR-based research in chemistry, biology, and materials science by attracting young scientists to these areas of research.

Conclusion: The United States needs to re-establish a level of support for state-of-the-art NMR research that will allow laboratories in the United States to regain a position of leadership in NMR-based research areas.

Factors That Contribute to the Declining Position of the United States in NMR-Based Research

Large-scale investments in both hardware and infrastructure fall into a range of funding that is a challenge for a federal agency to grant. The cost of a 1.2 GHz NMR magnet is approximately $20 million. There is currently no mechanism by which funds on this scale can be obtained through the conventional peer-review processes at NIH, NSF, or DOE.52 This cost is currently defined as “mid-scale instrumentation” based on the amount falling between the limits of the highest-funding single-investigator grant at NSF ($4 million Major Instrumentation Grant program) and the large-scale facility level (exceeding $100 million).53

Conclusion: The large capital investments needed for state-of-the-art high-field NMR instrumentation likely requires participation of and cooperation among multiple federal agencies. The wide-ranging impacts of these high-field instruments touch scientific communities from materials science to medicine, further justifying participation of multiple agencies.

The last 15 years have witnessed grass-root demands for higher-field NMR instrumentation that have gone unheeded.54 Although biological NMR in European and Asian universities has been amply supported by their national funding agencies, the last major investment by NIH in cutting-edge NMR instrumentation for biological sciences occurred in 2001–2002, when the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) established a program to fund 900 MHz (21.1 T) NMR instruments. (In 2010, approximately $8 million was awarded to investigators at the University of Maryland for one 950 MHz NMR instrument, through one-time instrumentation program funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.) When NIH officials were approached by this committee concerning this lack of support for high-field NMR research, the only examples that were presented as evidence for support were grants for funding of accessories and managerial support of NMR laboratories. When it was pointed out that the two federally funded 1.1 GHz NMR instruments and one federally funded 1.2 GHz NMR instrument in the United States were funded by NSF, NIH officials expressed the opinion that

___________________

52 National Research Council, 2013, High Magnetic Field Science and Its Application in the United States: Current Status and Future Directions, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/18355, p. 78.

53 Consumer Product Safety Commission, 2017, Petition Requesting Rulemaking on Magnet Sets (82 FR 46740).

54 T. Polenova and T.F. Budinger, 2016, “Ultrahigh Field NMR and MRI: Science at a Crossroads. Report on a Jointly-Funded NSF, NIH and DOE Workshop, Held on November 12–13, 2015 in Bethesda, Maryland, USA,” Journal of Magnetic Resonance 266:81–86.

developments in cryo-EM technology for experimental structure determination and AI-based methods for structure prediction had made the usefulness of NMR questionable.

As part of its activities, this committee sought out expert testimonies from U.S. and European academics, which ended up strongly disagreeing with such opinions. These presentations and literature data show that NMR measurements on biomolecular systems provide a wealth of information that is not accessible with any other approaches, and which escape the mostly static structural views afforded by current computational and microscopy techniques. Without attempting to be exhaustive, this committee heard how NMR had proven crucial in the following research areas: detecting tautomeric transient states that are key for defining translation events in nucleic acids, protein–protein interactions that define folding and misfolding, dynamic allosteric mechanisms, transient but crucial states adopted by intrinsically disordered fragments upon binding cellular fractions, in-cell conformational changes brought about by reversible post-translational modification processes, membrane-protein interactions and dynamics, and events happening in liquid-liquid, phase-separated compartments—all of which are missed by other emerging techniques.

In contrast to the United States, countries in Europe have established consortia that fund shared instrumentation, as well as maintenance and travel expenses for local or remote use of their ultrahigh-field NMR instrumentation. These consortia facilitate collaboration among multiple institutions located in different countries. A good example of this approach is the Pan-European Solid-State NMR Infrastructure for Chemistry-Enabling Access (PANACEA). The PANACEA initiative recognized the need for a large, multi-faceted effort to foster innovation and sought to amend this deficit with infrastructure for high-end solid-state NMR equipment and the high-level expert support required. European researchers across industry and academia—and with a conscious effort for trans-national access with geographical diversity and distribution, dedicated staff support, and promotion of gender balance—have focused on the following three actions to bridge eight centers: (1) a universal, vendor agnostic, data platform that conforms to findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) standards, (2) DNP NMR accessibility, and (3) ultrahigh-field solid-state NMR with ultrafast magic-angle spinning focused on unsolved problems in chemistry.

Conclusion: Given the cost of commercial ultrahigh-field NMR systems, it is clear that both the science and the service of these sophisticated machines can be best served by integrating them into multiuser, multiple-spectrometer facilities, capable of both serving a broad swath of the U.S. scientific community and offset operational and personnel costs over the decades-long lifetimes of these machines.

Cost is clearly an obstacle in the acquisition of ultrahigh-field NMR instrumentation. In 2014, a major U.S.-based manufacturer of instrumentation (Agilent) exited from the NMR business, perhaps encouraged by reduced level of federal funding for NMR instrumentation in the United States. Insufficient competition in commercial high-field NMR instrumentation has consequently resulted in substantial increases in costs, both for magnets themselves and associated instrumentation (consoles, probes, etc.). Escalating costs have discouraged universities, industrial research centers, and other research institutions from investing in and maintaining NMR facilities—even on facilities with only moderate field strengths.

In addition, the cost of installing and running NMR instruments has been strongly affected by recent liquid helium shortages and increases in liquid helium prices (discussed in more detail elsewhere in this report). Rising helium costs have forced the shutdown of single-investigator NMR laboratories and departmental NMR facilities in chemistry departments across the United States. All this is leading universities to stop renewing lines of research based on NMR, with a concurrent depletion in the output of trained students and postdocs that understand what MR is, how it works, and what its applications are. This is bringing about the loss of an entire future generation of scientists—imparting yet another hit to the U.S. scientific community, of a severity that no purchase of a single ultrahigh-field NMR spectrometer will by itself be able heal.

Finding: Lack of access to world-class NMR facilities—coupled with the rising costs of helium, paucity of financial support for expensive helium recycling and for the maintenance of individual instruments, and the departure of a major commercial NMR manufacturer from the market—have all contributed to the declining position of U.S. laboratories in NMR-based research fields, despite the abundance of scientific questions that are best addressed by NMR measurements. The impact of this decline goes beyond the instruments and is impacting the training of a new generation of scientists with expertise in the principles and uses of NMR.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN CHAPTER 1

Summarizing the findings in this chapter on MR spectroscopies, the committee found that

- NMR remains a very important and necessary field of research and affects many different communities of researchers, including chemistry, biochemistry, materials science, and in particular, pharmaceutical developments, drug discovery, and the petroleum-derived industries.

- Other methods available for investigation of structural chemistry are synergistic with NMR and should not be viewed as competition or replacements. NMR is uniquely suited for understanding dynamics, molecular interactions, and molecular mechanism aspects that microscopies and computations cannot currently elucidate.

- Instruments with high-field magnets, such as the 1.5 GHz SCH magnet at NHMFL, are very valuable for certain important applications of NMR, especially applications to spectroscopy of quadrupolar nuclei in materials and biomolecular solids.

- As stressed in this chapter, funding for and availability of stand-alone and of DNP-equipped ultrahigh-field NMR instruments in the United States since the 2013 NRC report has fallen far behind the levels in other countries, leading to a clear loss of leadership for the United States in NMR-based research. • Lack of competition and high development costs have placed the price of commercial ultrahigh-field instrumentation beyond the reach of most major single-agency funding schemes.

- Insufficient supply of and the high cost of helium continue to pose major threats to the research community. Because superconducting magnets require liquid helium for their operation, securing helium (and the budgets to pay for it) has been a challenge for NMR research for two decades. The committee’s strong recommendation is for reliable and cost-effective means to secure helium to be pursued by the U.S. government. Those recommendations fall in Chapter 7.

The following recommendations are based on the findings in this chapter.55

Key Recommendation 3: Within the next 2–3 years, the United States should implement the installation of multiple commercially made nuclear magnetic resonance instruments with magnetic fields in the 1.0–1.2 GHz range, covering all applications from physics and materials through pharma and biophysics and onto microimaging, and provide user access to these systems in the democratized science model followed by other national facilities. Such instruments should build on existing infrastructures, by relying on centers that have laid out management plans and proven track records of service to the scientific and industrial communities at large.

___________________

55 Note on numbering for recommendations. Because many are cross cutting, they have been pulled out and defined as “key recommendations.” The other set of recommendations are numbered based on the chapter in which they appear, with narrative and findings to support the recommendations.

Achieving this will require locating instruments at a variety of sites in the United States, preferably sites that have active local user communities and adequate staffing and engineering resources to keep the facilities running at a high-level for many years. Institutions that receive federal funding for such NMR instruments should be required to set aside 30–50 percent of the instrument time for outside users from academia and industry. In return, federal agencies should contribute to staffing, maintenance, and operation costs every year. A consortium structure, where institutions with these instruments share expertise, and coordinate their efforts and decisions in a way that maximizes their combined impact, could be envisioned. Twelve such instruments would bring high-field NMR instrumentation in the United States to approximately the same level as instrumentation in Europe. Support for ancillary equipment, including high-field dynamic nuclear polarization instrumentation, associated research supplies, and helium recycling systems should also be expanded.

The primary motivation for this recommendation is to provide the basic research community in the United States with state-of-the-art NMR instrumentation comparable to the instrumentation that is currently available to research communities elsewhere. Access to instruments with 1H NMR frequencies in the 1.0–1.2 GHz range may also benefit research and development efforts in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries, as discussed above, but is not the primary motivation for this recommendation.

Recommendation 1-1: The United States should emulate Europe’s approach and mandate that all federal agencies whose missions align with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)—foremost those supporting basic biomedical research—to fund the state-of-the-art NMR instrumentation that its industrial and academic communities have been requesting for years. The National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Energy should also find common ways to ensure support for the substantial operating costs that are needed to maintain these facilities.

Conclusion: While the previous recommendations would restore the competitiveness that the U.S. NMR community has lost over recent decades, additional sources of funding would be needed to pursue “moonshot” efforts restoring the U.S. supremacy in NMR and in MR in general.

In particular, the committee provides the following recommendation:

Key Recommendation 9: The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory demonstrated engineering capabilities that have led to the 36 T SCH magnet and 32 T all-superconducting magnet and that must be exploited to reach

new but achievable thresholds in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy via the MagLab-based construction of an all-superconducting 40 T system with parts per million homogeneity and sub-parts per million stability. This magnet should be complemented with the microwave and cryogenic capabilities needed for executing in it electron paramagnetic resonance and dynamic nuclear polarization experiments above 1.0 THz.

Conclusion: Helium supply represents a major ongoing risk to research, which stymies investments and hinders the training of the next generation of high-field and resonance scientists.

To offset this, the following recommendations are made, including Recommendation 7-1 from Chapter 7. For further details, see Chapter 7.

Key Recommendation 13: To secure helium access for research, as a short-term solution, the U.S. government (through the Department of the Interior or potentially the Department of Commerce) should immediately establish a royalty “in-kind” program for helium, whereby vendors extracting helium from federal lands would be required to refine and sell the helium to federally funded researchers. Doing so will enable preferred access to helium for basic research and development for physics, chemistry, biology, materials science, and medical magnetic resonance imaging support.

Recommendation 7-1: Secure helium supplies (short-term solution). The U.S. government should establish, as soon as possible, a new helium reserve through the Department of the Interior that can create a stockpile of helium for emergency use—analogous to the U.S. Petroleum Reserve.

Conclusion: Competition among vendors is critically needed, both in the ultrahigh-field NMR marketplace and in the marketplace for lower-field instruments that are required for training the next generation of NMR scientists.

Recommendation 1-2: Public–private and interagency partnerships inspired by the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 should be leveraged to encourage business development in magnetic resonance, with a particular effort at exploiting the opportunities opened by the extensive high-temperature superconductor efforts going on in the United States to develop the next generation of low-, intermediate-, and high-field resonance magnets.