The Current Status and Future Direction of High-Magnetic-Field Science and Technology in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 3 Superconducting Magnet Technology for Fusion

3

Superconducting Magnet Technology for Fusion

INTRODUCTION

Fusion has the potential to be a safe, on-demand, abundant, noncarbon-emitting and globally scalable energy source. Magnetic confinement fusion (MCF) uses magnetic fields to confine plasma for developing the scientific knowledge of plasma and advanced engineering to enable fusion. The MCF approach to harness fusion requires powerful magnetic fields, and production of these fields in the large scale for fusion is particularly challenging because they must operate reliably in a harsh environment in the proximity to the high energy neutron source and high temperature thermal sources, that are necessary components of a power producing device. Advances in high-field magnet technologies improved understanding of fusion plasma science and continues to play fundamental roles in burning plasma experiments. Recent U.S. strategic reports, including the 2020 report A Community Plan for Fusion Energy and Discovery Plasma Sciences: Report of the 2019–2020 American Physical Society Division of Plasma Physics Community Planning Process,1 the 2020 Fusion Energy Science Advisory Committee (FESAC) subpanel report Powering the Future: Fusion and Plasmas,2 and the 2021 National Academies of

___________________

1 Fusion Energy Scientific Advisory Committee, 2020, A Community Plan for Fusion Energy and Discovery Plasma Sciences: Report of the 2019–2020 American Physical Society Division of Plasma Physics Community Planning Process, https://usfusionandplasmas.org.

2 T. Carter, S. Baalrud, R. Betti, et al., 2020, Powering the Future: Fusion & Plasmas, A Report of the Fusion Energy Sciences Advisory Committee, https://usfusionandplasmas.org/wp-content/themes/FESAC/FESAC_Report_2020_Powering_the_Future.pdf.

Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report Bringing Fusion to the U.S. Grid,3 all emphasize the goal of a fusion pilot plant (FPP) to make 50–100 MW net electricity, extended to long-pulse, with a roadmap of design in 2020s, construction in 2030s, and operation in 2030s–2040s. The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, commonly referred to by its acronym ITER,4 represents the state-of-the-art burning plasma experiment currently under construction in the south of France. ITER adopted the low-temperature superconductor (LTS) magnet technology developed in the 1980s and 1990s.5 Magnet systems for present superconducting fusion devices, such as EAST6 in China, the Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research (K-STAR)7 in Korea, and W-7X8 in Germany, are expensive (~one-third of core machine cost). Devices beyond ITER will require significant technology improvements to make fusion economical. Strong technical progress over the past decades and recent private investments accelerated the development of a new U.S. vision and strategy for fusion research, development, and demonstration (RD&D). In March 2022, the United States announced the ambition to develop a “U.S. Bold Decadal Vision”9 to accelerate fusion energy research, development, and demonstration to enable an operating FPP on a decadal timescale. Several new initiatives within DOE, leveraging public–private and international partnerships, have been launched to advance the U.S. Bold Decadal Vision. Commercial fusion device designers shall consider a wide range of magnetic fields, operating temperatures in the promising magnetic field, and structural configurations to reduce operating costs. High reliability, repeatability, and maintainability are essential, particularly for the aggressive, compact high-field route to fusion commercialization. All existing superconducting fusion devices (Tore-Supra, LHD, EAST, KSTAR, and W7-X, including ITER currently under construction) used LTS, and none of these machines (Tore-Supra, LHD, EAST, KSTAR, or W7-X) are operated in the United States. Note, magnetic fusion tokamak devices commonly have three types

___________________

3 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021, Bringing Fusion to the U.S. Grid. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, https://doi.org/10.17226/25991.

4 ITER Organization, 2024, “ITER,” https://www.iter.org.

5 N. Mitchell and A. Devred, 2017, “The ITER Magnet System: Configuration and Construction Status,” Fusion Engineering and Design 123:17–25.

6 J. Li and Y. Wan, 2021, “The Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak,” Engineering 7(11):1523–1528.

7 K. Kim, H.K. Park, K.R. Park, et al., 2005, “Status of the KSTAR Superconducting Magnet System Development,” Nuclear Fusion 45(8):783.

8 T. Rummel, K. Riße, M. Nagel, et al., 2019, “Wendelstein 7-X Magnets: Experiences Gained During the First Years of Operation,” Fusion Science and Technology 75(8):786–793.

9 White House, 2022, “Readout of the White House Summit on Developing a Bold Decadal Vision for Commercial Fusion Energy,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/04/19/readout-of-the-white-house-summit-on-developing-a-bold-decadal-vision-for-commercial-fusion-energy.

of coils used for the magnetic fields: toroidal field coils (TF), central solenoid coils (CS), and poloidal field coils (PF). The highest-field LTS fusion magnet system being built today, ITER, uses 12 T TF and CS coils, and is limited by the wire and magnet technology at the scale and size for plasma experiments, typically requiring magnet systems of a few meters of large-bore diameter (TF, CS, and PF coils). Second-generation high-temperature superconductor (HTS) materials are available for producing >20 T at the magnet10 bore compared to LTS magnets that are limited to below 16 T for Nb3Sn as proposed in recent U.S. fusion energy systems studies (FESS) of the Fusion Nuclear Science Facility.11 HTS may enable higher-fusion power density and smaller device size. High-current-density cables are required for engineering design of FPPs to allow space for interior plasma components. High-current-density HTS magnets are particularly attractive in reducing the size of a fusion device and beneficial for compact tokamaks, owing to their space constraints.12 Successful HTS magnet development may enable the design of smaller and cheaper FPPs with a mission of demonstrating net electricity.13

Significant technology maturation efforts are under way by privately funded fusion startups with the goal to demonstrate maturity of HTS magnet technology based on the design concept of high-field compact devices to reduce size and potentially cost.14 For example, Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS)15 in the United States and Tokamak Energy (TE)16 in the United Kingdom have both adopted rare-earth barium copper oxide (REBCO) HTS for their reactor designs. SPARC (the name was chosen as an abbreviation of “Smallest Possible ARC”) is a high-field compact tokamak currently being developed by CFS using HTS with the goal of producing a practical reactor design for operation in 2025.17 CFS is demonstrating

___________________

10 Z.S. Hartwig, R.F. Vieira, D. Dunn, et al., 2023, “The SPARC Toroidal Field Model Coil Program,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 34(2):1–16, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2023.3332613.

11 C.E. Kessel, J.P. Blanchard, A. Davis, et al., 2018, “Overview of the Fusion Nuclear Science Facility, a Credible Break-in Step on the Path to Fusion Energy,” Fusion Engineering and Design 135:236–270.

12 J.E. Menard, 2019, “Compact Steady-State Tokamak Performance Dependence on Magnet and Core Physics Limits,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 377(2141):2017044, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2017.0440.

13 See Appendix C for related references.

14 B.N. Sorbom, J. Ball, T.R. Palmer, et al., 2015, “ARC: A Compact, High-Field, Fusion Nuclear Science Facility and Demonstration Power Plant with Demountable Magnets,” Fusion Engineering and Design 100:378–405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2015.07.008

15 Commonwealth Fusion Systems, 2024, “The Surest Path to Limitless, Clean Fusion Energy,” https://cfs.energy.

16 Tokamak Energy, 2024, “Delivering Clean, Secure, Affordable Fusion Energy in the 2030s,” https://tokamakenergy.com.

17 P. Rodriguez-Fernandez, A.J. Creely, M.J. Greenwald, et al., 2022, “Overview of the SPARC Physics Basis Towards the Exploration of Burning-Plasma Regimes in High-Field, Compact Tokamaks,” Nuclear Fusion 62(4):042003.

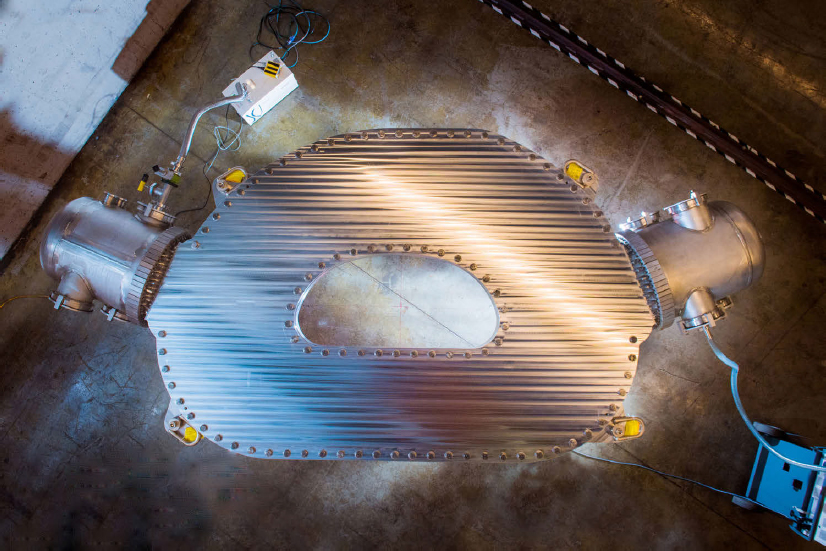

a 20 T, 20 K high-field coil approach for commercial fusion tokamak. A Toroidal Field Model Coil (TFMC), as seen in Figure 3-1, was built and tested in 2021 to generate a record of 20 T at 20 K on the D-shape HTS TFMC coil.18 The total magnetic stored energy in the CFS TFMC is 110 MJ (more than twice of that in the NHMFL 36 T series-connected-hybrid user magnet available a few years ago) and about 270 km of REBCO tape was used. The SPARC tokamak requires a total of 18 toroidal field coils to generate a magnetic field of 12 T at the plasma center, directed the long way around the torus, resulting in a 23 T peak field on each of the TF coils. The total stored magnetic energy in SPARC TF coils is more than 2 GJ. The CFS TFMC tests have demonstrated the enormous potential that high fields can bring to high-field compact fusion. A current density of 750 A/mm2 in the stack of REBCO tape in the CFS TFMC was tested at 20 T and 20 K, which resulted in ~150 A/mm2 coil winding pack current density in a noncable in conduit

SOURCE: D. Chandler, 2021, “MIT-Designed Project Achieves Major Advance Toward Fusion Energy,” MIT News, September 8; image courtesy of Gretchen Ertl, CFS/MIT-PSFC, 2021.

___________________

18 D.G. Whyte, B. LaBombard, J. Doody, et al., 2023, “Experimental Assessment and Model Validation of the SPARC Toroidal Field Model Coil,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 34(2):1–18.

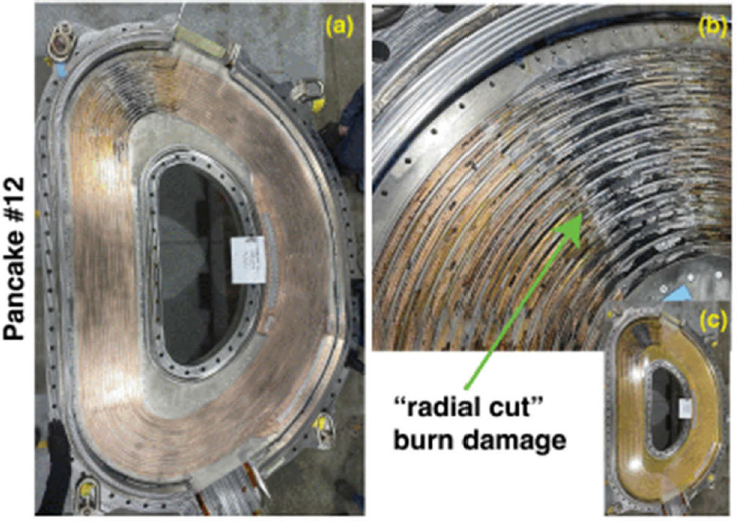

cable (CICC) configuration. Critical engineering issues such as quench detection and protection of overheating resulting in burn damage of the windings, as seen in Figure 3-2, are being resolved to meet performance goals and demonstrate coil operation repeatability and reliability. The high cost and technical risks of high-field HTS coils may hinder their design use in an FPP, particularly if the rapid progress implied by present scale-up plans sees any checks.

The cost of a fusion magnet system scales with, at least, the square of the magnetic field, defined as B, and the volume of the plasma (B2V)0.6.19 The high-field compact reactor requires not only advances in magnet technology, but also innovations to address other critical scientific and technology gaps (nuclear fusion materials, fusion fuel cycle, plasma confinement, blanket technology). Considering system optimization with all these competing requirements, simply generating the highest magnetic field may not be the preferred route for commercially viable fusion device.

SOURCE: D.G. Whyte, B. LaBombard, J. Doody, et al., 2024, “Experimental Assessment and Model Validation of the SPARC Toroidal Field Model Coil,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 34(2):1–18, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10316632. CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

___________________

19 S. Entler, J. Horacek, T. Dlouhy, and V. Dostal, 2018, “Approximation of the Economy of Fusion Energy,” Energy 152:489–497, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.03.130.

Finding: Magnets are a primary machine core cost driver for magnetic fusion devices. FPP concepts, and the supporting superconducting magnet technology needs to be developed in parallel to meet aggressive U.S. fusion power program schedules and ensure timely demonstration of reliable, affordable, superconducting magnets before a U.S. FPP is successfully built and operated. Significant technology maturation efforts are under way by privately funded fusion startups with the goal to demonstrate mature HTS magnet technology for fusion applications, but critical issues remain to be resolved to meet machine performance goals and demonstrate coil operation repeatability and reliability.20

SCIENCE DRIVERS

High-field magnets enable compact fusion devices. Magnets are the core feature of magnetic fusion, and it is desirable to develop magnets with higher fields, operating temperatures, and reliability, constructed with streamlined manufacturing processes and reduced production costs. While increasing the field in magnetic fusion devices brings not only huge benefits for fusion energy power density, but also systems engineering complications in terms of space for component integration and heat power deposition, there are several key innovations that could be potential game changers for fusion energy. This follows from the rapid maturing in HTS magnet technology that has been demonstrated, including industrial-scale manufacturing of second generation (2G) high temperature superconductors (HTS) using the cuprate superconductor YBa2Cu3O7−x (YBCO) coated conductor in long piece lengths for significantly improved performance,21 as well as from the growing experience that is being gathered from operating high-field HTS magnets worldwide in other applications. The U.S. fusion energy research program is guided by the Long-Range Plan (LRP) “Powering the Future: Fusion and Plasmas” developed by the Fusion Energy Sciences Advisory Committee (FESAC).22 As the U.S. fusion industry pursues an FPP, the three science drivers defined in the LRP, which include “sustain a burning plasma,” “engineer for extreme conditions,” and “harness fusion energy,” will need to be balanced with research toward fusion magnet materials and enabling technology to close critical science and technology gaps.

___________________

20 Y. Zhai, D. Larbalestier, R. Duckworth, Z. Hartwig, S. Prestemon, and C. Forest, 2024, “R&D Needs for a US Fusion Magnet Base Program,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity.

21 A. Molodyk, S. Samoilenkov, A. Markelov, et al., 2021, “Development and Large Volume Production of Extremely High Current Density YBa2Cu3O7 Superconducting Wires for Fusion,” Scientific Reports 11(1):2084.

22 T. Carter, S. Baalrud, R. Betti, et al., 2020, Powering the Future: Fusion & Plasmas, A Report of the Fusion Energy Sciences Advisory Committee, https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1995209.

Plasma Confinement and Stabilities

The strength of the magnetic field is a design driving parameter for fusion power reactors in achieving plasma confinement and stability conditions while providing both thermal insulation and external pressure to hold the hot plasma stably. Fusion power produced in a tokamak is proportional to the strength of the magnetic field to the fourth power, B4.23 Therefore, a factor of two increase in magnetic field leads to sixteen times the amount of fusion power for a given device size. In turn, at fixed fusion power, a smaller device can be built using a higher field. Therefore, the size, timeline, and economics of a magnetic-confinement fusion power plant are strongly dependent on the quality of the superconducting magnets.24 Box 3-1 shows schematics for tokamak and stellarator fusion reactors. Generally speaking, stellarators are at least 2–3 times more stable than tokamak. Typically, the 7 T magnetic field at the plasma center is the upper limit for stellarators. Spherical tokamak (ST) of apple-core-shaped plasma is also more stable than conventional tokamak of donut-shaped plasma.25

Radial Build and Systems Integration Challenges

Magnets are integral features of magnetic fusion configurations, and it is desirable to develop magnets with higher fields, operating temperatures, and reliability, which are constructed with streamlined manufacturing processes and reduced production costs.26 Although high-field magnets enable compact fusion devices, there are engineering limits in systems configurations of space for component integration and heat power deposition, and there are several key innovations that need to be developed and matured in parallel in order for high-field HTS to become a potential game changer for fusion energy. Fusion magnets are particularly challenging because of their relatively large diameter and volume.

___________________

23 B.N. Sorbom, J. Ball, T.R. Palmer, et al., 2015, “ARC: A Compact, High-Field, Fusion Nuclear Science Facility and Demonstration Power Plant with Demountable Magnets,” Fusion Engineering and Design 100:378–405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2015.07.008.

24 Plasma Science and Fusion Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2024, “Magnetic Fusion Energy,” https://www.psfc.mit.edu/research/topics/high-field-pathway-fusion-power.

25 X.R. Wang, A.R. Raffray, L. Bromberg, et al., 2008, “ARIES-CS Magnet Conductor and Structure Evaluation,” Fusion Science and Technology 54(3):818–837.

26 T. Carter, S. Baalrud, R. Betti, et al., 2020, Powering the Future: Fusion & Plasmas, A Report of the Fusion Energy Sciences Advisory Committee, https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1995209.

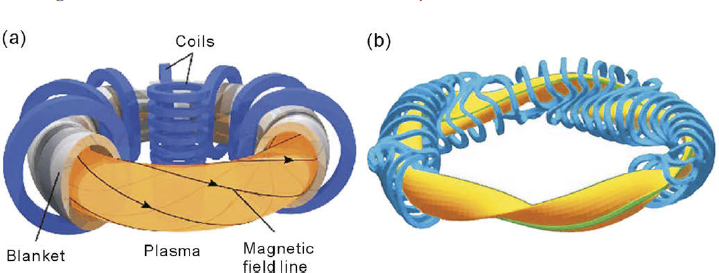

BOX 3-1

Tokamak and Stellarator Fusion Reactors

The schematics given in Figure 3-1-1 show concepts for magnetic confinement of the high-temperature plasmas for fusion reactors.

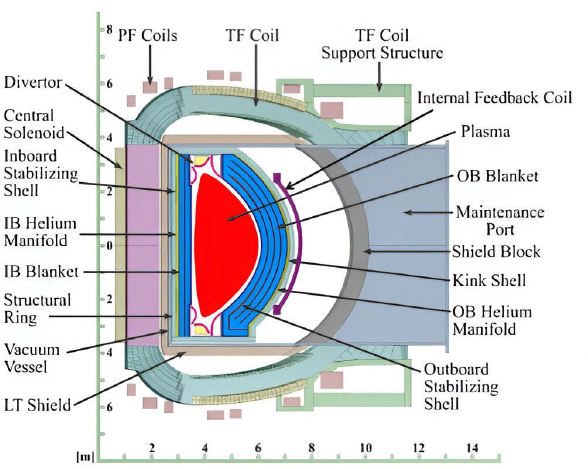

As described in published reviews, the tokamak design offers the ability to operate at high temperatures, and the stellarator magnetic field is understood to be potentially more stable than the tokamak.a Figure 3-1-2 shows the scale of such systems.

SOURCE: Y. Xu, 2016, “A General Comparison Between Tokamak and Stellarator Plasmas,” Matter and Radiation at Extremes 1(4):192–200, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mre.2016.07.001. Copyright © 2016, AIP Publishing. CC BY.

NOTE: Notice the scale at the left is a fusion reactor 8 m in height.

SOURCE: Y. Zhai, A. Otto, and C. Kessels, 2021, “Conceptual Design of High Field Central Solenoid for Fusion Nuclear Science Facility,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 31(5):9366964, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2021.3063056. © 2021 IEEE. Reprinted with permission from IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity.

__________________

a Meschini, S., F. Laviano, F. Ledda, D. Pettinari, R. Testoni, D. Torsello, and B. Panella, 2023, “Review of Commercial Nuclear Fusion Projects,” Frontiers in Energy Research 11:1157394, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2023.1157394.

High Heat Load and First Wall Power Handling

High-field HTS magnets could also be critical tools to advance understanding of the structure and function of the integrated fusion materials. National and international research activities and goals are outlined by the U.S. fusion magnet community, the fusion magnet international consortium,27,28 and in the U.S. Bold Decadal Vision for Commercial Fusion Energy scientific vision report.29

Finding: There is a pressing need for a strong U.S. public program in fusion magnet science to help deploy commercial fusion energy on the timelines proposed by private companies per the U.S. Bold Decadal Vision. To define such a new public program, a formal, in-depth, community-led process is being developed by establishing stakeholder roles, prioritizing scientific issues, and proposing actionable research thrusts as part of the new fusion-enabling technology roadmap.

Existing and Planned High-Field Test Facilities

Most existing superconducting magnet systems operated for fusion experiments are at field strengths of 3–5 T at the plasma center, and at a 6–9 T maximum field on the TF, CS, and PF coils for tokamaks and stellarators as shown in Table 3-1. A high-current cable consisting of hundreds or a thousand superconducting wires is typically needed, and is tested at a unique large-bore size (e.g., 300 mm), with a high field of 11.5 T, and at a conductor test facility, such as SULTAN30 at EPFL in Switzerland, because these high current conductors are used to wind the large-size fusion coils.

There is today an inability to fully test HTS materials, cables, and magnets in the fusion-relevant conditions required to develop and qualify advanced superconducting magnets for an FPP. New facilities are needed to fill this gap worldwide. Importantly, the United States can leverage existing capabilities and infrastructure to deliver these facilities in a cost- and schedule-effective manner and lead the

___________________

27 Y. Zhai, R. Duckworth, Z. Hartwig, D. Larbalestier, S. Prestemon, and C. Forest, 2023, Summary Report of the First Fusion Magnet Community Workshop, March 14–15, https://drive.google.com/file/d/15nzVopvmnysq1JeQHExT0km5YPI9FUrC/view.

28 N. Mitchell, J. Zheng, C. Vorpahl, et al., 2021, “Superconductors for Fusion: A Roadmap,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(10):103001.

29 White House, 2022, “Readout of the White House Summit on Developing a Bold Decadal Vision for Commercial Fusion Energy,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/04/19/readout-of-the-white-house-summit-on-developing-a-bold-decadal-vision-for-commercial-fusion-energy.

30 B. Stepanov, P. Bruzzone, K. Sedlak, and G. Croari, 2013, “SULTAN Test Facility: Summary of Recent Results,” Fusion Engineering and Design 88(5):282–285.

TABLE 3-1 List of High-Field Magnetic Fusion Devices

| System and Location | Major Radius (m) | B(T) at Plasma center | Bmax (T) on Magnet | No. TF Coils | Stored Energy | Wire | Configuration | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITER, Francea | 6.3 | 5.2 | 12 | 18 | 41 GJ | Nb3Sn | Tokamak | ITER IO |

| W7X, Germanyb | 5.5 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 20 | 360 MJ | NbTi | Stellarator | VAC, EAS, EM |

| JT-60-SA, Japanc | 2.96 | 2.25 | 5.65 | 18 | 1.06 GJ | NbTi | Tokamak | ICAS, ASG, Alstom |

| Tore Supra | 2.44 | 4.5 | 9.0 | 18 | 600 MJ | NbTi | Tokamak | CEA |

| K-STAR, Koread | 1.8 | 3.5 | 7.2 | 16 | 470 MJ | Nb3Sn | Tokamak | ASG |

| EAST, Chinae | 1.8–1.9 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 16 | 200 MJ | NbTi | Tokamak | ASIPP |

| LHD, Japan | 3.9 | 4.0 | 10.5 | 2 | 1.6 GJ | NbTi | Stellarator | Hitachi |

| E-DEMO | 9.1 | 5.3 | 12 | 16 | 150 GJ | Nb3Sn/HTS | Tokamak | EU |

| J-DEMO, Japanf | 8.5 | 5.94 | 13.7 | 16 | 149 GJ | Nb3Sn | Tokamak | JA |

| SPARC, United States | 1.85 | 12.2 | 23 | 16 | >2 GJ | HTS | Tokamak | CFS, MIT |

a Mitchell, N., and A. Devred, 2017, “The ITER Magnet System: Configuration and Construction Status,” Fusion Engineering and Design 123:17–25.

b Rummel, T., K. Riße, G. Ehrke, et al., 2012, “The Superconducting Magnet System of the Stellarator Wendelstein 7-X,” IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 40(3):769–776, https://doi.org/10.1109/SOFE.2011.6052220.

c Boulant, N., and L. Quettier, 2023, “Commissioning of the Iseult CEA 11.7 T Whole-Body MRI: Current Status, Gradient–Magnet Interaction Tests and First Imaging Experience,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 36(2):175–189, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01063-5.

d Kim, K., H.K. Park, K.R. Park, et al., 2005, “Status of the KSTAR Superconducting Magnet System Development,” Nuclear Fusion 45(8):783.

e Li, J., and Y. Wan, 2021, “The Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak,” Engineering 7(11):1523–1528.

f Ivanov, D., F. De Martino, E. Formisano, et al., 2023, “Magnetic Resonance Imaging at 9.4 T: The Maastricht Journey,” Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine 36(2):159–173, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-023-01080-4.

NOTE: ASG, ASG Semiconductor Company; ASIPP, Institute of Plasma Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences; CEA, French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission; CFS, Commonwealth Fusion Systems; EAS, type of superconducting wire produced by Bruker; EAST, Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak; E-DEMO, European Demonstration Power Plant; EM, Electron Microscopy; EU, European Union; ICAS, Innovation and Consulting on Applied Superconductivity (company); ITER, International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; IO, ITER Organization; JA, Japan; J-DEMO, Japan Demonstration Power Plant; K-STAR, Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research; LHD, Large Helical Device; MIT, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; SPARC, Smallest Possible ARC; VAC, Consortium Vacuumschmelze GmbH.

world in this critical area for fusion.31 There are three types of facilities that are essential for advancing high-field superconducting magnets for a variety of future FPP concepts and to advance the necessary science and engineering knowledge, but they are presently unavailable within the worldwide superconducting community.

Access to suitable facilities for large-test volume, moderate-field coil testing is required to develop and qualify new superconducting cables and coil construction methods. With support from DOE FES, the U.S. fusion community could rapidly design, construct, and operate new facilities to provide large-bore (e.g., 1–2 m), moderate central field (e.g., 10+ T at the bore center) test capabilities for 3D superconducting cable configurations and representative-scale coils. The magnetic fields could be steady-state or pulsed (5–10 T/s), both of which are important for assessing the different magnets required in magnetic confinement fusion systems. Capabilities should include the ability to perform Paschen breakdown testing in representative environments,32 which was shown by the ITER superconducting magnet development program to be critical.33 Furthermore, building such capabilities would make the United States a world-leader in superconducting magnet test capabilities, building on the new DOE FES-High Energy Physics (HEP) 15 T superconducting straight cable test facility at Fermi National Laboratory (FNAL) that is presently under construction. Presently, there are essentially no user-accessible, large-bore, moderate-field magnet facilities worldwide suitable for testing representative scale superconducting cables and model coils; however, existing U.S. capabilities could be leveraged to provide an effective platform, as follows:

- General Atomics ITER Central Solenoid (CS) manufacturing capabilities and testing infrastructure could be highly leveraged to provide a large-bore, moderate-field test facility with steady-state or pulsed magnetic fields.

- The MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center Magnet Test Facility could be upgraded with a large-bore solenoid to provide a moderate field and a large volume for the reaction.

- Fermilab possesses several existing fast-turnaround facilities that can be used to test REBCO tape stacks under different temperature and field conditions. Several instrumentation tools for quench detection and characterization have been under development over the past years, including fiber optics, quench antenna, acoustic sensors, and AI techniques. Those techniques are promising to develop robust and reliable tools for characterizing quench

___________________

31 G.V. Velev, D. Arbelaez, C. Arcola, et al., 2023, “Status of the High Field Cable Test Facility at Fermilab,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 33(5):1–6.

32 J. Knaster and R. Penco, 2011, “Paschen Tests in Superconducting Coils: Why and How,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 22(3):9002904.

33 N. Martovetsky, K. Freudenberg, G. Rossano, et al., 2022, “Testing of the ITER Central Solenoid Modules,” IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 50(11):4292–4297.

- propagation and detection on REBCO tapes and cables. Current variation in tape manufacturing and response to overstress under different cable configurations are important considerations to reduce potential damage from localized defects or hotspots to validate designs.

- There are also discussions at NHMFL for the construction of a user-accessible test facility as a critical component of the construction of a small-bore (32–50 mm warm bore), 60 T NHMFL user-magnet. NHMFL had for many years a 20 T, 195 mm RT bore (161 mm at 4.2 K) magnet that was taken out of service in 2016 and replaced by a 14 T, 161 mm bore superconducting magnet at the Applied Superconductivity Center (ASC)-NHMFL, which is currently being used for fatigue testing of many HTS coils with currents up to 10 kA. The 20 cm bore magnet is now being replaced by a larger-bore magnet (~20 T at 25 cm) and will be accessible with high-current supply to NHMFL users.

- Large-scale HTS fusion magnets require critical current characterization of significant amounts of superconductor at moderate-to-high magnet fields (12–20 T) and low temperatures (10–30 K). Mechanical characterization could also be performed. Reel-to-reel equipment capable of making such measurements does not exist and needs to be developed. Private and public fusion energy efforts would benefit from the use of such equipment to (1) maintain a public database of all HTS manufacturer performance, (2) enable superior quality assurance and quality control methods for processing HTS for use in large-scale magnets, and (3) support manufacturers in developing superior conductors. This development could leverage existing efforts at Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) to develop advanced HTS characterization techniques, including Hall sensor arrays and high-precision, DC-current source arrays integrated with a high-resolution data acquisition system and novel magnetization methods. These techniques also explore the use of physics-based analysis with AI and machine learning as a more comprehensive approach to HTS characterization.

Because designing, building, and operating representative-scale magnets is essentially the only way to create and grow a specialized workforce in magnet technology, the construction and operation of a suite of new magnet test facilities in the United States represents an unprecedented opportunity to intentionally recruit and train new personnel. Importantly, as both private and federally sponsored fusion programs expand toward delivering an FPP in an era of retirement of key personnel who developed and built the present fleet of U.S. fusion devices, there is a critical shortage of personnel with experience in fusion magnet technology.

Many of the same challenges that must be solved for fusion magnets listed in Table 3-1 (e.g., achieving magnetic fields exceeding 20 T at the conductor, handling

enormous electro-mechanical loads and surviving intense radiation environments) are shared with the DOE HEP community. Next-generation colliders to succeed the Large Hadron Collider will require the same test facilities that are now needed for fusion energy. Thus, there is a significant opportunity for multiple areas within DOE (FES, HEP, nuclear physics [NP], etc.) to utilize the same new facilities, which will also enhance collaboration and knowledge exchange.

Magnet Field Strength Limits

LTS fusion magnet systems at 12–16 T using TF and CS coils adopted Nb3Sn cable in conduit conductor (CICC) technology, while the compact high-field tokamak magnet systems identified in Table 3-1 at 20 T (CFS and TE) adopted REBCO-coated conductors as the conductor of choice. High-temperature superconductor (HTS) technology has significantly impacted the field of fusion energy in the past decade, from reducing the projected size, cost, and schedules of future FPPs to driving, in large part, the creation of a private fusion energy industry, which is now comprised of dozens of companies with a total of $5 billion in capital investment. Indeed, four of the eight recent winners in the DOE Milestone-based Fusion Development Program have fusion concepts that fundamentally depend on the success of HTS magnet technology.

Beyond 12 T for Compact High-Field Fusion Magnets

Pushing field strengths above 12 T at a large-scale compact fusion energy system that require bore sizes of 2 or more meters requires use of alternative wire technology and advances in engineering design. Nb3Sn wire technology and CICC technology is relatively mature and used in the manufacture of ITER magnets at large bore sizes. Unlike NbTi wire that is flexible and can be wound after formation into a superconducting wire, Nb3Sn technology typically needs a wind first and then reacts at higher temperatures to become a superconductor. This adds significant equipment investment and engineering effort that is especially challenging at the larger-magnet bore sizes of fusion devices. On the other hand, react-and-wind (R&W) coil technology is important for very large coils for fusion application. Advantages of R&W include (1) reducing thermal strain, giving superior performance (relative to wind-and-react); (2) avoiding need for huge reaction-ovens; (3) avoiding the cable-in-conduit approach to enhance overall engineering current density in winding pack to improve thermal control capability; and (4) enabling drastic simplification of coil winding approach. To this end, it is highly advantageous for fusion coils to avoid large costly ovens needed for heat treatment (such as that for ITER and demonstration power plant (DEMO)s). The R&W coil technology is available for the cuprate superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2Oy (BSCCO) 2223

and REBCO conductors, and it was previously used for Nb3Sn coils such as the Levitated Dipole Experiment (LDX) large, levitated dipole coil and the common core coil at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL). The R&W is also developed for BSCCO 2212, but this needs manufacturing scale-up.

HTS materials may be an important alternative to allow for the design of high-field, compact fusion magnet systems above 12 T, but the technology is less mature. Only one HTS TF model coil has been tested to reach 20 T at 20 K, once by CFS and MIT at the MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center utilizing the conductor;34 the design improvement of quench resilience has yet to be demonstrated. The 17 T Wisconsin HTS Axisymmetric Mirror (WHAM) solenoid coil has been delivered but has not been proven quench resilient.

MRI demand for a large volume of LTS NbTi wire helped drive the quality, cost, and availability of this wire. According to an industry representative from one of the major MRI manufactures, there are no near-term plans to adopt HTS for use in clinical MRI systems.35 Therefore, currently, other than the recent interest in the fusion community, there is no large commercial application to drive the maturation of the technology.

In the United States, a new high-field fusion magnet system above 12 T in ITER TF and CS coils is likely to be designed and built by private industry with the public funding support of fundamental materials science, HTS conductors and cables, and large-scale magnet test facilities. The amount of conductors required to support the number of large fusion devices is significant (e.g., 270 km long REBCO conductors used in the CFS TFMC, ~10,000 km REBCO coated conductor is being delivered to CFS for SPARC, and ~20,000 km REBCO conductor is needed for a commercial fusion reactor like ARC; hundreds of ARC reactors are needed to bring fusion to the U.S. grid) and may be sufficient to support and drive R&D activities necessary to address long-term supply-chain issues on wire manufacturers. Other potential industrial applications with sustained volume, such as electrical power cables and wind turbines, are required drivers of the wire technology. Certain types of HTS wire technology, for example REBCO, are being scaled in manufacture for multiple planned fusion projects. REBCO allows for winding after reacting, which could greatly simplify design when compared with Nb3Sn react after wind technology. The angular dependence and anisotropic material properties could also trigger other mechanical and thermal issues such as tape delamination. In addition, manufacturing defects, potential winding damage of the coated conductor,

___________________

34 Y. Li and S. Roell, 2021, “Key Designs of a Short-Bore and Cryogen-Free High Temperature Superconducting Magnet System for 14 T Whole-Body MRI,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(12):125005, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ac2ec8.

35 GE Healthcare Stuart Feltham presentation to the committee.

as well as screening current-induced issues could also trigger quench failure and damage to the coil.

But REBCO or other HTS materials such as BSCCO may require adaptation for use in design of large-scale fusion magnet systems that do not have additional requirements of field stability or persistent operation field uniformity that is required in MRI systems.

Although fusion startup companies such as CFS and Tokamak Energy adopted REBCO-coated conductor for their high-field compact fusion tokamak designs, other HTS conductors may be more advantageous for fusion because:

- Fusion B-fields typically vary spatially (helical field in toroidal systems, fringe field at coil edges)

- Thus, fusion REBCO coils must use B ⊥ tape performance as shown in Figure 6-1

- BSCCO 2212 is isotropic for all B-values

- High engineering current density Nb3Sn can achieve magnetic field of B <17 T

Both Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8 (Bi-2212) and Nb3Sn are available commercially with similar fabrication processes, filaments in metal matrix, and minimal screening currents and no delamination as in all coated conductors.

STATUS OF MAGNETIC CONFINEMENT FUSION AROUND THE WORLD

ITER is the world’s biggest experiment on the path to fusion energy. It is an international nuclear fusion research and engineering project aimed at creating energy through a fusion process similar to that of the Sun.

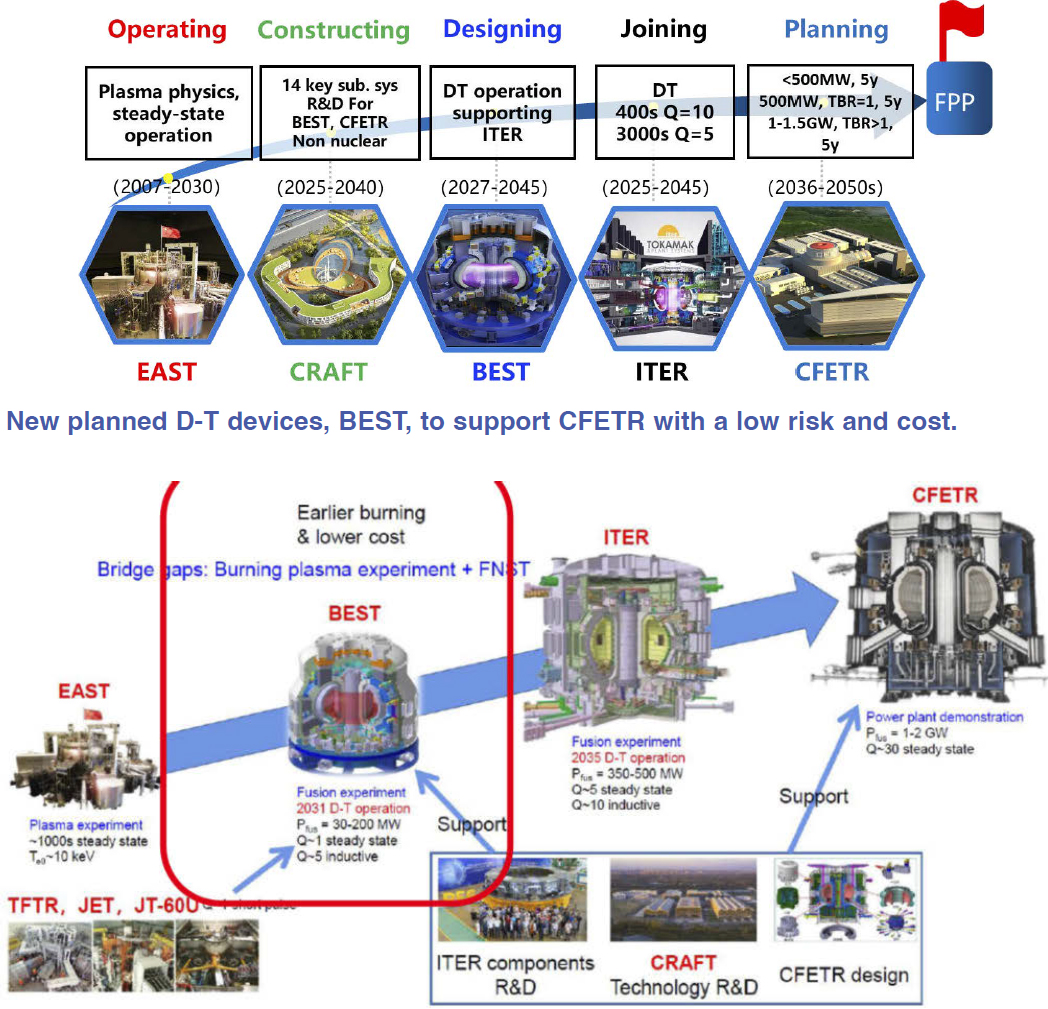

There are several DEMO power plant design activities around the world. The most noticeable efforts with significant government funding support include that in Europe (E-DEMO) and China (CFETR), as shown in Figure 3-3.

Gap Summary

Large-Bore High-Field Fusion Magnets

Magnetic confinement fusion (MCF) devices at high magnetic fields require large quantities of superconducting wire. Coils with field at the conductor above 12 T require Nb3Sn LTS conductor or potentially HTS wire. Significant progress in applying HTS materials into high-current cables and high-field magnets has been made in the last decade; however, there remains a high-degree of technical risk

NOTE: BEST, Burning plasma Experimental Superconducting Tokamak; CFETR, Chinese Fusion Engineering Test Reactor; CRAFT, Comprehensive Research Facilities for Fusion Technology; EAST, Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak; ITER, International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; JET, Joint European Torus; JT-60, Japan Torus-60; TFTR, Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor.

SOURCE: Courtesy of Yuntao Song, presented at the Fusion Power Associates 43rd Annual Meeting and Symposium 2022.

in many areas of HTS magnet technology as well as in many nonfusion scientific opportunities now being considered. Thus, the development and demonstration of new superconducting magnet technologies based on HTS materials is essential to meet the aggressive schedules to establish an FPP in the 2030s proposed by both private companies and the DOE FES program.

Finding: A large quantity of HTS conductor is needed for the next-step fusion device such as FPP, fusion power plant, and beyond. For example, more than 10,000–20,000 km long, 4 mm wide REBCO tape is needed for the CFS SPARC machine to be operational in 2025. About 15 years ago, the United States was the first to demonstrate manufacturability of REBCO coated conductor.36 Present HTS conductor procurement in the emerging fusion industry, however, is largely from overseas suppliers. There is a pressing need for the United States to regain the industrial fabrication capability to meet the need for fusion.

Finding: Apart from the 20 T high-field magnet in Table 3-1, which is planned to be designed with a compact TF and CS magnet using HTS materials, the remaining coil systems such as PF coils at 11.7 T noted above have relied on Nb3Sn wire technology. None of these magnets were designed or manufactured in the United States even although much of NbTi wire technology was derived from superconducting wire research that was performed in the United States for accelerators science.

Finding: High-field magnet systems, usually considered lifetime components of a fusion power plant, will have to sustain large electromechanical loading and fatigue stress cycling at cryogenic temperatures under intense neutron fluences. Such magnet systems store tens of gigajoules of energy within their magnetic fields, which needs to be properly handled in the event of a quench to avoid damage to the magnet system. Robust quench detection and mitigation strategies are essential for LTS and HTS conductors.

Synergies

There are synergies between accelerator, high-field research, and fusion magnets. R&D capabilities that can be leveraged for synergies need to be identified

___________________

36 D.F. Lee and A.W. Murphy, 2008, ORNL Superconducting Technology Program. Superconductivity for Electric Systems. Annual Report for FY 2007, Department of Energy, Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability, Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory, http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2011/ph240/kumar1/docs/ORNL-HTSPC-20.pdf.

so that best strategies can be developed to maximize the use of existing cable test facilities within the U.S. Magnet Develop Program. Those existing capabilities can be implemented with the large-bore HTS cable test facility currently under construction at FermiLab.37 This facility will serve as a test stand for HTS cables in high-field (15 T) and at variable temperatures and high current (100 kA). There are, however, also fusion-specific magnet challenges such as the fast ramp rate needed for initiating plasma operation in a tokamak. ITER requires that coils not quench or fast discharge after plasma disruption. Table 3-2 lists maximum field variation (dB/dt) in fusion magnet systems for various tokamaks.

Unlike previous fusion research programs fully funded by public money, the committee notes that the other difference from HEP and high-field research is that the public-funded base program will need to be complementary and supportive to the private effort; the rapid changing U.S. fusion program landscape driven by the private sector.

Path Forward

Recent advances in HTS38 and magnet technology39,40,41 have induced a profound change in the field of fusion energy in the past decade. This technology has enabled compact FPP conceptual designs based on tokamaks,42 spherical

___________________

37 G.V. Velev, D. Arbelaez, C. Arcola, et al., 2023, “Status of the High Field Cable Test Facility at Fermilab,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 33(5):1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2023.3242853.

38 A. Molodyk, S. Samoilenkov, A. Markelov, et al., 2021, “Development and Large Volume Production of Extremely High Current Density YBa2Cu3O7 Superconducting Wires for Fusion,” Scientific Reports 11(1):2084, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81559-z.

39 E.S. Bosque, Y. Kim, U.P. Trociewitz, C.L. English, and D.C. Larbalestier, 2024, “System and Method to Manage High Stresses in Bi-2212 Wire Wound Compact Superconducting Magnets,” https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2019245646.

40 D.C. Van Der Laan, J.D. Weiss, U.P. Trociewitz, et al., 2020, “A CORC® Cable Insert Solenoid: The First High-Temperature Superconducting Insert Magnet Tested at Currents Exceeding 4 kA in 14 T Background Magnetic Field,” Superconductor Science and Technology 33(5):05LT03, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ab7fbe.

41 Z.S. Hartwig, R.F. Vieira, D. Dunn, et al., 2023, “The SPARC Toroidal Field Model Coil Program,” IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 34(2):1–16, https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2023.3332613.

42 B.N. Sorbom, J. Ball, T.R. Palmer, et al., 2015, “ARC: A Compact, High-Field, Fusion Nuclear Science Facility and Demonstration Power Plant with Demountable Magnets,” Fusion Engineering and Design 100:378–405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2015.07.008.

TABLE 3-2 Maximum Field Variation in Fusion Magnets

| System and Location | dB/dt (T/s) on TF | dB/dt (T/s) on CS | Wire | Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITER, Francea | 1.66–6.55 | 1.0–5.5 | Nb3Sn | Tokamak |

| K-STAR, Koreab | 1–3 | 8 | Nb3Sn | Tokamak |

| EAST, Chinac | 1–3 | 7 | NbTi | Tokamak |

| SPARC, United States | 1–5 | 5–10 | HTS | Tokamak |

a N. Mitchell and A. Devred, 2017, “The ITER Magnet System: Configuration and Construction Status,” Fusion Engineering and Design 123:17–25.

b K. Kim, H.K. Park, K.R. Park, et al., 2005, “Status of the KSTAR Superconducting Magnet System Development,” Nuclear Fusion 45(8):783.

c J. Li and Y. Wan, 2021, “The Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak,” Engineering 7(11):1523–1528.

NOTE: EAST, Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak; ITER, International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor; K-STAR, Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research; SPARC, Smallest Possible ARC.

tokamaks,43 stellarators,44 and magnetic mirrors,45 and more recently has propelled the rise of the $5 billion private fusion energy industry; however, significant gaps exist between the state of the art in superconducting magnets today and what will be needed to deploy high-availability, economically viable FPPs in sufficient number to contribute to a clean energy economy.46 The path forward for the high-field approach requires further development of wire and magnet technology, integrated magnet test facilities capable of operating at large bore sizes above 13 T. A comprehensive program to review alternative fusion magnet designs utilizing superconducting magnet laboratory expertise to validate affordability, repeatability, and reliability is needed.

Finding: A fusion magnet public program is urgently needed, and it will need to support a successful demonstration of reliability and repeatability of high-field magnets in compact tokamaks developed by both public and private sectors as one of the promising configurations for FPP operation.

___________________

43 J.E. Menard, B.A. Grierson, T. Brown, et al., 2022, “Fusion Pilot Plant Performance and the Role of a Sustained High Power Density Tokamak,” Nuclear Fusion 62(3):036026, https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-4326/ac49aa.

44 J.A. Alonso, I. Calvo, D. Carralero, et al., 2022, “Physics Design Point of High-Field Stellarator Reactors,” Nuclear Fusion 62(3):036024, https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-4326/ac49ac.

45 J. Egedal, D. Endrizzi, C.B. Forest, and T.K. Fowler, 2022, “Fusion by Beam Ions in a Low Collisionality, High Mirror Ratio Magnetic Mirror,” Nuclear Fusion 62(12):126053, https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-4326/ac99ec.

46 N. Mitchell, J. Zheng, C. Vorpahl, et al., 2021, “Superconductors for Fusion: A Roadmap,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(10):103001, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/ac0992.

Finding: Based on lessons learned from ITER and the CFS TFMC project, it is critical to develop a comprehensive understanding of conductor and cable performance and scalability under physics and engineering constraints to determine promising configurations.

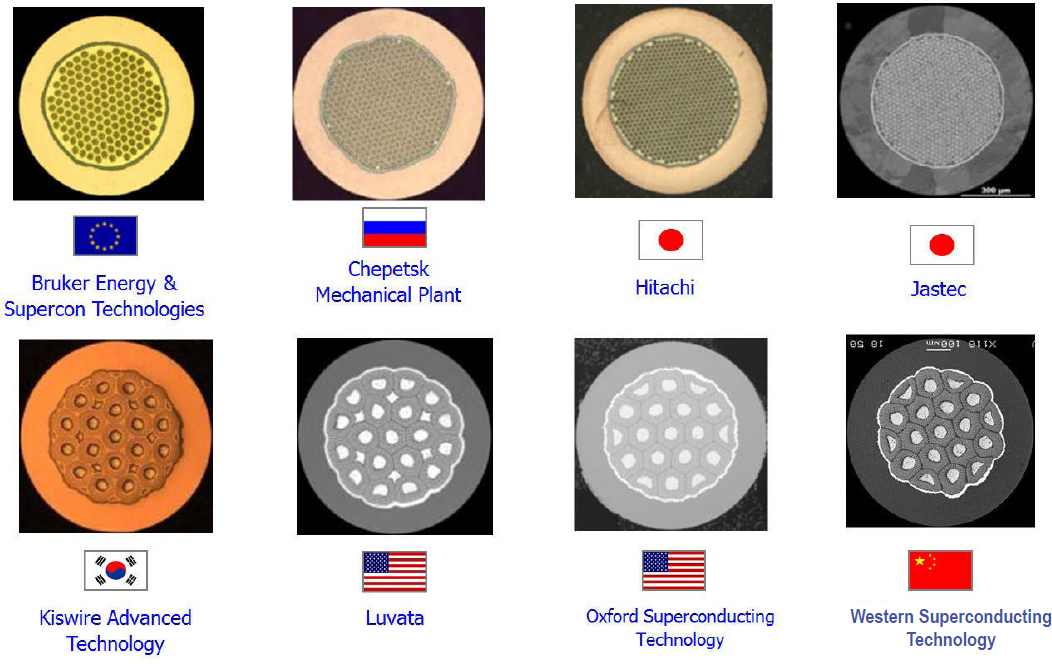

Superconductor fabrication of filaments in a metal support matrix such as NbTi, Nb3Sn, and BSCCO-2212 was extensively developed and explored. Figure 3-4 lists the ITER conductor zoo where each of these wires can be manufactured into long lengths (up to 9 km), there is no screening current, and conductor suppliers maintain high manufacturing uniformity.

React-and-wind coil technology is also important for very large coils. This technology is readily available for BSCCO 2223 and REBCO-coated conductors. It has been previously used for Nb3Sn (BNL common core coil and Levitated Dipole Experiment (LDX) large, levitated dipole coil). It has also been developed for BSCCO 2212 by U.S. manufacturers but needs manufacturing scale-up to:

- Reduce thermal strain, giving superior performance (relative to wind-and-react)

SOURCE: A. Devred, 2013, “Testing Celebrated at Last Conductor Meeting,” ITER NEWSLINE, March 25, https://www.iter.org/newsline/singleprint/-/1541. Courtesy of Arnaud Devred.

- Avoid the need for huge reaction ovens, similar to ones used by ITER

- Avoid the cable-in-conduit approach, to enhance coil current density in winding pack and improve thermal control

- Enable drastic simplification of coil winding approach

To Address These Gaps

The high-magnetic-field community gathered the input of the fusion community, including academia, national laboratories, private fusion companies, superconductor manufacturers, and government on critical R&D gaps that might be closed by a public program in the field of fusion superconducting magnets.47 Through this community process, the committee has identified four types of magnet test facilities that are presently unavailable and will be essential for advancing the following multiple fusion energy concepts:

- Large coil volume, moderate magnetic field testing in steady-state and pulsed fields

- Cryogenic irradiation of magnet materials in fusion-relevant neutron fluence and spectra

- Large-scale cryogenic hydrogen coolant characterization and demonstration flow loops

- High-throughput, high-field and low-temperature, reel-to-reel HTS characterization

There are three additional benefits to be realized through new magnet test facilities. First, the design, construction, and operation of such facilities address a critical shortage of workforce specialized in superconducting magnets, from technicians to engineers to faculty; such personnel are critical to the growth of the nascent fusion energy industry. Second, advancing high-field superconducting magnets is a shared technical challenge with the HEP and NP community for next-generation experiments; test facilities will serve multiple DOE missions. Third, DOE could leverage existing capabilities in the U.S. private and public sectors to budget and schedule more effectively in order to create world-class test facilities to advance fusion energy.

HTS technology has significantly impacted the field of fusion energy in the past decade, from reducing the projected size, cost, and schedules of future FPPs to driving, in large part, the creation of a private fusion energy industry, which is

___________________

47 Y. Zhai, R. Duckworth, Z. Hartwig, D. Larbalestier, S. Prestemon, and C. Forest, 2023, Summary Report of the First Fusion Magnet Community Workshop, March 14–15, https://drive.google.com/file/d/15nzVopvmnysq1JeQHExT0km5YPI9FUrC/view.

now comprising companies with a total of $5 billion in capital investment. Indeed, four of the eight recent winners in the DOE Milestone-based Fusion Development Program have fusion concepts that fundamentally depend on the success of HTS magnet technology. This reality reflects the centrality of advanced superconducting magnets to a variety of fusion energy concepts including tokamaks, spherical tokamaks, stellarators, mirrors, and more. This is because superconducting magnet systems typically represent one of the largest capital costs in a magnetic fusion device; they are also one of the most significant technical risks. Such systems, usually considered lifetime components of a fusion power plant, must sustain large electromechanical loading and fatigue stress cycling at cryogenic temperatures under intense neutron fluences. Such magnet systems store tens of gigajoules of energy within their magnetic fields, which must be properly handled in the event of a quench to avoid damage to the magnet system. Robust quench detection and mitigation strategies are essential. Furthermore, many of the proposed FPP concepts require magnetic fields more than the approximately 12 T peak field-on-coil available from the highest-field low-temperature superconductor, Nb3Sn. This requires the use of HTS, particularly REBCO, and new magnet design modalities to achieve the large-volume, ~20 T fields demanded by these new FPP designs. Significant process in applying HTS materials into high-current cables and high-field magnets has been made in the past decade; however, there remains a high degree of technical risk in many areas of HTS magnet technology as well as many fusion scientific opportunities now being considered. Thus, the development and demonstration of new superconducting magnet technologies based on HTS materials is essential to meet the aggressive schedules to establish an FPP in the 2030s proposed by both private companies and the DOE FES program.

The facilities discussed above will play a significant role in ensuring the success of FPPs by tackling the nuclear challenges to the magnets of such facilities. Furthermore, the science and engineering learning developed will be important for economic and operations optimization of commercial fusion power plants. The facilities discussed below (in this chapter) would largely use existing technology and be based on similar or even proof-of-concept facilities. Thus, while formal design and siting activities will be required as a precursor to construction, there are no significant scientific or engineering challenges that need to be resolved.

Conclusion: Understanding the performance evolution of superconductors under fusion-relevant conditions is essential for fusion power plant design, operation, and costing because the magnet systems typically comprise a significant fraction of the core capital cost and are considered lifetime components. Ideally, testing superconductors requires exposing such materials to fusion-relevant neutron fluences with matched energy spectra under similar operating conditions to a fusion magnet (i.e., temperature, field, and transport current). Characterization

of critical current dependence in magnetic field, temperature, field angle, and strain as a function of neutron fluence is essential without an intervening thermal warm up (e.g., in situ critical current testing). Such testing is not only essential to characterize present superconductors but to help guide R&D toward more radiation-tolerant superconductors. Furthermore, the property evolution of essential magnet materials (i.e., insulation, copper, steels, instrumentation, and fiber optics) under radiation loads is of high interest, as is assessing new candidate materials for these applications.

Conclusion: Integrated magnet test facilities that are presently unavailable and will be essential for advancing multiple fusion energy concepts and should include (1) large-volume, moderate-magnetic-field coil testing in steady-state and pulsed fields; (2) cryogenic irradiation of magnet materials in fusion-relevant neutron fluence and spectra; and (3) large-scale cryogenic hydrogen coolant characterization and demonstration flow loops. There are three additional benefits to be realized through new magnet test facilities. First, the design, construction, and operation of such facilities addresses a critical shortage of workforce specialized in superconducting magnets, from technicians to engineers to faculty; such personnel are critical to the growth of the nascent fusion energy industry. Second, advancing high-field superconducting magnets is a shared technical challenge with the HEP community for next-generation colliders; such facilities will play important dual roles. Third, the substantial current capabilities in the U.S. private and public sector could be leveraged by DOE to budget and schedule effectively to create world-class test facilities to advance fusion energy.

Conclusion: The design and manufacture of new large-bore and large-volume high-field HTS magnet systems will be conducted by industry, with complementary support from private or public funding. The magnet companies rely on HTS manufacturers and adapt their designs to currently available HTS technology. The physics and engineering challenges for fusion, on the other hand, may require closer public–private partnership, including integrated design of conductors, high current cables, and demonstration coils for rapid maturation of HTS magnet technology for fusion.48

Conclusion: HTS materials and wires are developing rapidly, driven this time by the fusion energy industry; progress in this area could help adapt HTS wire development suitable for use in MRI systems to enable higher field whole body MRI/MRS systems and larger bore animal systems. Advancing the technology of manufacturing methods that allow for design of large-scale magnets and sufficient

___________________

48 Ibid.

production volume would quickly be adopted by industry for design of magnets. These are needs for the United States to be competitive with the next generation of magnets and be leaders in net zero energy production and leaders in health sciences.

Key Recommendation 1: The National Science Foundation and Department of Energy are urged to double their support for the development of wire technologies within 2–3 years, including support to re-establish the U.S. high-temperature superconductor (HTS) wire industry and the establishment of U.S. test facilities appropriate for characterizing HTS conductors and cables at high field and stress. This should focus on both the fundamental level (universities and laboratories) and production level (industry).

Key Recommendation 2: The National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and National Institutes of Health should develop collaborative programs to accelerate the development of high-temperature superconductor (HTS) magnet technology to support development of high-field magnetic resonance imaging, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, fusion, and accelerator magnets. For example, a large-bore solenoid (900 mm+), high-field (14 T+) magnet demonstrator employing HTS technologies, ideally with ramp capability (5–10 T/s), should be commissioned to develop the foundational design method and wire technology that has potential applications across high-magnetic-field science.

Recommendation 3-1: U.S. industry needs to increase its capacity to produce wire within the next 3–5 years to support the expected large demand from magnet production and fusion efforts.

The resulting demonstrator magnet, when complete, will serve as a valuable facility for testing HTS components of various shapes and sizes not possible today.

Recommendation 3-2: The U.S. funding agencies should partner with the rapidly emerging fusion industry to develop a fusion magnet education program to generate a trained and essential workforce at all levels (PhD-level scientists, engineers, and skilled technicians) by leveraging capabilities of U.S. universities, national laboratories, and the fusion industry.

Recommendation 3-3: U.S. funding agencies should consider programs to support advanced cooling technologies for high-field magnets toward commercial fusion. For example, gas cooling at 20 K (helium, neon, and hydrogen, etc.).

Recommendation 3-4: U.S. funding agencies should consider supporting a fusion conductor program to advance the development of superconductors that use wires other than restacked rod process wire.

Advanced fusion conductor R&D aims at simpler wire fabrication process and reduced cost Nb3Sn wire (e.g., rod and restack process), and which is focused on high-field quality, filament uniformity, etc.