The Current Status and Future Direction of High-Magnetic-Field Science and Technology in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 8 Stewardship

8

Stewardship

INTRODUCTION

The importance and the role of high-magnetic-field facilities is to provide highly complex and unique equipment to perform fundamental science and applied research of new materials, energy, biology, biochemistry, biophysics, medicine, and technology.

Research with application of high magnetic fields necessitates specialized facilities with dedicated equipment, infrastructure, and highly competent and qualified personnel. Owing to complex equipment, safety conditions and high operational costs, these facilities need effective management and organization, which is critical to the viability of research requiring the use of high magnetic fields. High-magnetic-field facilities require development of next-generation magnets and magnetic materials, and training and coaching of high-magnetic-field scientists.

In this chapter, the committee reviews which large high-magnetic-field capabilities currently exist in the United States and compare them to the facilities available to scientists worldwide. The committee also discusses access models to high-magnetic-field facilities in the United States and worldwide. Second, the committee will review the important role of decentralized magnetic field facilities in the United States and worldwide in research, in bringing the field forward, and in the training of the next generation of scientists and suggest an increase and centralized support for the decentralized magnetic field facilities. It should be noted here that smaller decentralized facilities (e.g., for nuclear magnetic resonance [NMR]) in the United States are distributed all over the United States either as instruments

that belong to individual faculty or as mid-size facilities with multiple instruments that are managed by the institution and some of them are open to the regional and national user community. These mid-size facilities are absolutely critical for training of the next generation of scientists and for the generation of preliminary results that enable scientist to acquire experimental time at the high field instruments and to plan for the optimal use of the extremely valuable experimental time at the high-magnetic-field facilities.

DEMOCRATIZATION OF THE SCIENTIFIC COMMUNITY’S ACCESS TO HIGH MAGNETIC FIELDS IN THE UNITED STATES AND WORLDWIDE

Centralized High-Magnetic-Field Facilities United States

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL), commonly known as the MagLab,1 in Florida is the major centralized high-magnetic-field laboratory in the United States. This centralized laboratory includes three sites (Florida State University, University of Florida, and Los Alamos National Laboratory). Since its inception in 1990, the MagLab has operated a world-leading, High-magnetic-field user program that hosts researchers from thousands of universities, laboratories and businesses from the United States and worldwide, carries out in-house research in support of the user program, maintains facilities and develops new magnets and instrumentation, and conducts education and outreach activities.

The seven MagLab user facilities include the DC Field Facility, the Electron Magnetic Resonance Facility, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Pulsed Field, Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy (AMRIS), High B/T Facility, and Ion Cyclotron Resonance (ICR) user facilities. The DC Field Facility hosts the largest and highest-powered magnet laboratory in the world. The High B/T Facility leads the world in its unique combination of high magnetic fields with ultralow temperatures in a reduced electromagnetic noise environment. The Pulsed Field Facility (PFF) in Los Alamos is the only pulsed field user facility in the United States and a center for exceptional condensed matter physics research. By studying materials under extreme magnetic field conditions, NHMFL-PFF scientists make essential contributions to fundamental materials science, energy research, and

___________________

1 Los Alamos National Laboratory, “National High Magnetic Field Laboratory-Pulsed Field Facility,” https://organizations.lanl.gov/physical-sciences/materials-physics-applications/nhmfl, accessed June 12, 2024.

stewardship of the nation’s nuclear stockpile.1 Table 81 lists the pulsed field magnets currently available at NHMFL-PFF and their capabilities.

The MagLab also possesses other unique sets of high-magnetic-field records:

- Its 36 T super-conducting (SCH) magnet is the highest-field instrument supporting routine solid state NMR measurements in materials, as well as specialized continuous-wave (CW) EPR measurements exceeding 1 THz frequencies. The SCH achieves this with an approximately 0.1 ppm homogeneity and stability, thanks to a lock stabilization system and to a powered resistive insert magnet being run in series connection with a high inductance superconducting outsert.

- In 2017, the Maglab also installed the first all-superconducting (SC) 32 T magnet using REBCO tape for the innermost coils. (3.4 cm bore at 4.2 K). While possessing a lower resolution than the 36 T SCH it allows one to collect measurements from full positive to full negative fields.

- Since 1999, the MagLab has operated such a system with field up to 45.2 T. In the summer of 2022, the magnet laboratory in Hefei, China also reached 45.2 T.

- The MagLab has held the record for DC resistive magnets for all but 3 of the past 29 years. There is great demand among MagLab users for the present 41.5 T in a 3 cm room-temperature bore.

TABLE 8-1 Available Pulsed Field Magnets at NHMFL-PFF

| Magnets | Capabilities |

|---|---|

| 100 Tesla Multi-Shot Magnet | The Pulsed Field Facility has the world’s only scientific program that has delivered scientific results in nondestructive magnetic fields up to and exceeding 100 Tesla. |

| 65 Tesla Multi-Shot Magnet | The most widely used pulsed field magnet system for users: The Pulsed Field Facility provides approximately 6,000 pulses each year in four separate user cells. |

| 300 Tesla Single-Turn Magnet | This magnet is capable of producing a field in excess of 300 Tesla and is proven to leave the sample probe intact in fields up to 240 Tesla. This is currently NHMFL’s highest magnetic field generating capability and requires specialized technique development and sample preparation owing to the rapidly changing field. |

| 60 Tesla Controlled Waveform Magnet | This magnet is currently a world-unique capability that allows the user to specify the magnetic field profile optimized for the investigation of physics in very high magnetic fields. |

SOURCE: Based on data from Los Alamos National Laboratory, “Pulsed Magnets for Cutting-Edge Science,” https://organizations.lanl.gov/physical-sciences/materials-physics-applications/nhmfl, accessed July 24, 2024.

- In its 105 mm ultrawide bore 21.1 T system, the MagLab has provided for almost two decades the highest field system for performing MRI experiments in mice and rats.

- For more than a decade, the MagLab has provided access to the world’s highest field ICR magnet, at 21 T. (12.3 cm room temperature bore, 5 ppm over 6 cm diameter × 10 cm long cylinder.)

Access to the MagLab User Facilities

Access to the MagLab user facilities has been transparent. The committee summarizes below the primary information available for users to plan their experiments at the MagLab user facilities.

- Schedule of experiments is online: The schedule for all user experiments is posted online with information on the timeslot, instrument, usernames, and the title of the experiments being conducted.

- Access: Facilities are open to all scientists.

- Costs: Experimental time is free of charge.

- Selection of proposals for experiments is via a competitive process

- Application deadlines: The facility accepts proposals throughout the year.

The application process for magnet time is similar to the process for major Department of Energy (DOE) facilities, which includes the following steps:

- Plan the experiment.

- Prepare the documentation.

- Prepare a proposal and prior results report.

- Create a user profile.

- Submit a request online.

- Upload files and provide details about the proposed experiment.

- Reporting: after experimental time is awarded and the experiment has been completed a report has to be submitted.

The access model for the MagLab is very similar to most other high-magnetic-field facilities that exist worldwide.

Centralized High-Magnetic-Field Facilities in the World

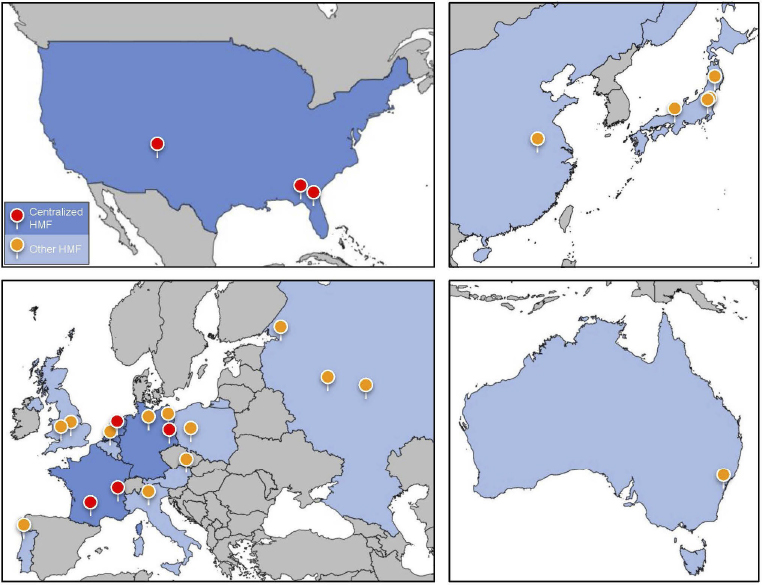

Figure 8-1 shows the distribution of high-field centralized magnetic field facilities in the world.

NOTE: The countries shaded with darker blue contain a centralized high-magnetic-field facility and the lighter blue countries contain other high-magnetic-field facilities.

SOURCE: Staff generated by Mason Klemm.

Below is a description of the facilities by country and region:

-

Europe—In Europe, there are three major high-magnetic-field facilities on four sites, all now linked together as the European Magnetic Field Laboratory (EMFL):

- Dresden High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Hochfeld-Magnetlabor Dresden (HLD). According to their website,2 the HLD has accepted proposals for magnet time and hosted users since the beginning of 2007. The coils available at the HLD produce both high magnetic fields (above 70 T with 150 ms pulse length) and smaller ones (60–65 T, with 25–50 ms pulse lengths). Pulsed magnets up to 85 and 95 T with 10 ms pulse length have

___________________

2 Helmholtz Zentrum Dresden Rossendorf, 2024, “Dresden High Magnetic Field Laboratory User Program,” https://www.hzdr.de/db/Cms?pOid=23421&pNid=1482.

-

- been commissioned in 2016. HLD is now accepting proposals for experiments up to 85 T or even up to 95 T. Energy for the pulsed magnets is provided by a modular 50 MJ capacitor bank—the only one of its kind in the world. The free-electron laser facility FELBE next door allows high-brilliance infrared radiation to be fed into the pulsed field cells of the HLD, thus enabling unique high-field magneto-optical experiments in the 4 to 250 μm range.

- Laboratoire Nationale des Champs Magnétiques Intenses (LNCMI) in Grenoble (DC) and Toulouse (Pulsed).

- The High Field Magnet Laboratory (HFML) in Nijmegen. According to their website,3 scientists can apply for magnet time by submitting a proposal. They have one application process together with the other three European high-field magnet laboratories. There are two deadlines each year: May 15 and November 15. Researchers who are granted access can use the installation and all available auxiliary equipment. If necessary, the researcher can get support from their staff, they also help with local arrangements (accommodation, visa, travel, etc.).

- Other ancillary magnetic field laboratories in Europe include:

- Poland—International Laboratory of High Magnetic Fields and Low Temperatures in Wroclaw

- Portugal—Centro de Fisica at the University of Porto, Porto Institute of Electronic and Magnetic Materials

- Italy—Institute of Electronic and Magnetic Materials in Parma

-

Germany

- Humboldt High Magnetic Field Center in Berlin

- High Field Magnet Laboratory in Braunschweig

- Belgium—Pulsed Field Facility in Leuven

- Austria—Astromag in Vienna

-

United Kingdom

- Nicholas Kurti Magnetic Field Laboratory Oxford

- Wills Physics Laboratory in Bristol

-

Japan—In Japan the High Magnetic Field Collaboratory has been established that organizes the collaborative research organization of Japanese high-magnetic-field facilities, which provide opportunities for experiments in the various magnetic fields by combining steady and pulsed magnetic fields:

- International MegaGauss Science Laboratory (IMGSL) at the Institute for Solid State Physics (ISSP) in the University of Tokyo

___________________

3 Radboud Universiteit, “Use the HFML-FELIX Facilities,” https://www.ru.nl/en/hfml-felix/users-and-partners/using-the-facilities, accessed March 28, 2024.

-

- Center for Advanced High Magnetic Field Science (AHMF) at the Graduate School of Science in Osaka University

- High Field Laboratory for Superconducting Materials (HFLSM) at the Institute for Materials Research (IMR) in Tohoku University. They provide opportunities for borderless experiments in the various magnetic field ranges up to 1200 T by combining steady and pulsed magnetic fields.

-

China

- Steady High Magnet Field Facility (SHMFF) from the National Academy of Science is located in Hefei, the capital city of Anhui provinces. It serves as one of the national major scientific and technological infrastructure projects of China. According to its website,4 it offers scientific researchers access to unique equipment housed in state-of-the-art facilities, and onsite experts to help visiting researchers take advantage of and make best use of the capabilities. Researchers also have the opportunity to collaborate with the experienced scientists and engineers to advance their scientific research.

- Wuhan National High Magnetic Field Center is a pulsed magnetic field research center with the high magnetic field ranging from 50 to 75 T for 50 to 2250 ms. Power is provided by a capacitor bank, and a 1000 V lead-acid battery that has delivered a 90.6 T field.5

-

Russia

- Kurchatov Institute in Moscow

- All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Experimental Physics (VNI-IEF) in Sarov

- Ioffe Institute and State Technical University in St. Petersburg

- Australia—National Magnet Laboratory in Sydney

CENTRALIZED USER FACILITIES, NEUTRON, SYNCHROTRON IN COMBINATION WITH HIGH MAGNETIC FIELDS

Neutrons and X rays yield insights into entirely new states of matter that cannot be observed by other methods. National facilities (Spallation Neutron Source, High Flux Isotope Reactor, the National Institute of Standards and Technology [NIST], Synchrotrons at Argonne and Stanford) are operating as very well-developed user facilities. This chapter explores the huge scientific advances that can be made by combining the neutron, synchrotron, and XFEL facilities with high-magnetic-field

___________________

4 Chinese Academy of Sciences, “High Magnetic Field Laboratory,” http://english.hmfl.cas.cn, accessed March 28, 2024.

5 See Wuhan National High Magnetic Field Center, “About Us,” https://whmfc.hust.edu.cn/english/About_Us.htm, accessed April 11, 2024.

research in the United States and compares those with the development of a combination of these techniques worldwide. Here the committee concentrates on the achievements, challenges, and gaps in the stewardship of these large user facilities.

Spallation Neutron Source and High Flux Isotope Reactor at Oak Ridge National Laboratory

The DOE scientific user facilities—the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) and the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS)—are DOE-sponsored research facilities open to researchers for advancing research in science and technology. HFIR and SNS, two of the world’s most advanced neutron scattering research facilities, offer 30 instruments covering a wide range of science and capabilities. Beam time is granted through the user program and is free of charge with the condition researchers publish their results, making them available to the scientific community.

National Institute of Standards and Technology Center for Neutron Research

The NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR) is a national user facility that provides cold and thermal neutron measurement capabilities to researchers from academia, industry, and other government agencies. NCNR offers neutron scattering and chemical analysis instruments to all qualified users. All proposals will be critically reviewed for scientific merit by experts external to NCNR.

Beam Time Allocation in Neutron Centers

There are several ways for users to obtain beam time on SNS, HFIR, and NCNR instruments. The primary method is through the proposal system. Calls for proposals are issued twice per year. Proposals are normally peer-reviewed, first by technical experts on the scientific topic of the proposals, then by the Beam Time Allocation Committee, which provides specific recommendations for instrument time. The instrument staff schedule the time for approved proposals. At NCNR users can obtain instrument time through scientific collaborations with NCNR staff. The Sample Environment group helps researchers in any phase of the experiment with sample environment issues: planning an experiment, loading a sample, preparing equipment for use, mounting at the spectrometer, and trouble-shooting if any problems are encountered. Any equipment used to alter a sample’s environment falls under care of dedicated personnel, from a milli-Kelvin dilution refrigeration system to a 1600° Celsius furnace, the equipment spans a large temperature range. Beyond precise temperature control, there is also a superconducting magnet system

with fields up to 15 T and various other environment altering equipment for parameters such as pressure, voltage, and current.

Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source at Cornell

The Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) is a National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded, high-magnetic-field X-ray beamline. In collaboration with the MagLab, a new beamline will be built at CHESS for experiments, which will allow researchers to conduct precision X-ray studies of materials in persistent magnetic fields that exceed those available at any other synchrotron. On October 28, 2020, NSF awarded CHESS $32.6 million to build a high-magnetic-field beamline. In partnership with CHESS, the MagLab and the University of Puerto Rico (UPR), the high-magnetic-field beamline will serve convergence research between two large NSF facilities and train students from UPR to become future technology leaders.6 The high-magnetic-field beamline should be finished in 2025–2026.

Magnets

The beamline will feature a custom low-temperature superconducting (LTS) magnet generating continuous fields as high as 20 T. The beamline will be designed to accommodate even higher fields from future magnets, which will become feasible as high-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnet technology matures.

Science Capabilities and Vision

Priorities are (1) delivering high photon flux, (2) allowing precise control of polarization and beam size over a wide range of incident energies, and (3) exploiting sophisticated analyzer and detector systems to enable multimodal X-ray measurements.

The first generation high-magnetic-field magnet design produces a maximum DC field of up to 20 T using established magnet technology, and large optical access to the sample with conical angles approaching 50°. The result is a facility that will triple the range of DC magnetic fields that are available in the United States for several key synchrotron techniques, while also improving on the precision available, and opening entirely new avenues of investigation. Nearly all techniques currently used at MagLab facilities average across the entire bulk of a sample, with no real-space or momentum-space resolution. Synchrotron X rays offer new capabilities for

___________________

6 Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, 2023, “CHESS Celebrates Construction Milestone with Wilson West Open House,” https://www.chess.cornell.edu/chess-celebrates-construction-milestone-wilson-west-open-house.

spatially resolved interrogation of heterogeneous samples with tunable sensitivity to specific phases, symmetries, structures, and elements.

Operation and User Access to CHESS

Access to this new beamline (as for the current beamlines) will be provided based on competitive proposal submissions and a rigorous peer-review process.

STRUCTURE AND STEWARDSHIP OF HIGH-FIELD NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE FACILITIES

University-based NMR facilities and individual laboratories in the United States have been the backbone of magnetic field research in the United States. Thousands of high-impact publications in the fields of biology, chemistry, and material sciences have been conducted at these decentralized facilities. They also provide the essential training space for the next generation of scientists in the magnetic field research, who are absolutely needed for advancement of science and technology development in the United States. However, the committee members have seen a sharp decline in the number of the decentralized facilities in the United States, driven by dramatically increasing costs for acquisition, maintenance, and operation of NMR instrumentation. By contrast to centralized facilities where NMR use is partly subsidized, individual laboratories and facilities face ever increasing costs that can no longer be accommodated from individual grants. As an example, the funding for an R01 National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant with modular budget was $250,000 per year in 2002, and this number has NOT been increased in the last 22 years. Taking inflation into account, the amount of funding per grant is less than half than it was in 2002 and thereby not sufficient to support expensive user fees from facilities, especially as increase of costs for operation (like for spare parts, service contracts, and Helium) further inflate the costs that have currently to be recovered from user fees. The United States is unique in this lack of support for NMR. As noted in Chapter 1, this has been in stark contrast with the situation in other parts of the world including Japan, China, and Europe. As a case in point, Europe counts with both national and pan-European NMR consortia that provides access to high-field NMR facilities and organizes user access to these facilities with peer reviewed applications. In exchange for their very specialized instrumentation, these user facilities devote specific percentages of their time to servicing the awarded proposals, and in return get paid for maintenance and operation. The closest facilities in the United States that approach this mode of operation are the MagLab (servicing more than 300 NMR users per year), NMRFAM at Wisconsin, and the New York Structural Biology Center. None of these facilities, however,

delivers access to 1.2 GHz NMR as done by European Centers at Florence, Frankfurt, Utrecht, Lille and others.

Finding: The U.S. NMR community suffers from both insufficient funding for maintaining, upgrading, and operating the individual laboratories and departmental facilities that have cemented NMR industrial and scientific activities over the decades, and lack as well the major ultrahigh-field NMR facilities of the kind which have been set up in European countries over the last decade.

Conclusion: While the MagLab is well funded and operates high-field instruments with no costs for the users, the decentralized facilities in the United States are strongly disadvantaged as they have to currently recover all their operation and maintenance costs by user fees, which is difficult to recover from grants owing to the high increase of costs. It would be important for the NMR community that the facilities which will host the proposed new high field 1–1.2 GHz instruments as well as the National Gateway Ultrahigh Field NMR Center at Ohio State University, NMRFAM in Wisconsin, and the new Network for Advanced NMR (NAN), to name just a few, will be funded for operation and maintenance by a joint effort of NSF, NIH, and DOE and that user access could be managed similar to the MagLab and other national labs (like synchrotron accelerators, XFELs, and Neutron facilities), that is, proposals could be selected for experiment time by a rating by a panel of independent experts and the awarded experiment time should be free of charge for the users.

Key Recommendation 4: The National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Energy should together establish an operation funding model, which provides both funds for operating and maintaining local nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) facilities and laboratories, as well as major investments seeking the siting and utilization of ultrahigh-field NMR facilities in institutions and laboratories with a track record of NMR discoveries and service.

Regarding the balance between pushing toward higher magnetic field strengths versus maximizing the science impact of currently accessible fields by making them more readily available to the users: The investment in a 1.5 GHz instrument based on the 36 T SCH magnet designed and built at NHMFL has given the United States an unparalleled research instrument. The commissioning by the MagLab of the 32 T all-superconducting LTS/HTS magnet also proves that, in combination with the stabilization and shimming technologies developed at the MagLab, these magnets can also serve NMR needs. The next decade needs to see the leveraging of these efforts, into the next generation of solid-state NMR instrumentations. Therefore:

Key Recommendation 9: The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory demonstrated engineering capabilities that have led to the 36 T SCH magnet and 32 T all-superconducting magnet must be exploited to reach new but achievable thresholds in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy via the MagLab-based construction of an all-superconducting 40 T system with parts per million homogeneity and sub-parts per million stability. This magnet should be complemented with the microwave and cryogenic capabilities needed for executing in it electron paramagnetic resonance and dynamic nuclear polarization experiments above 1.0 THz.

As noted in Chapter 1, this push to ever-higher fields needs to be accompanied by substantial investments in commercially made instruments, either purchased with an existing vendor or developed by a public–private partnership—for example, between the MagLab and a commercial vendor. In support of this the committee here reiterates the conclusion from Chapter 1.

Conclusion: Given the cost of commercial ultrahigh-field NMR systems, both the science and the service of these sophisticated machines can be best served by integrating them into multiuser, multiple-spectrometer facilities, capable of both serving a broad swath of the nation’s scientific community and offsetting operational and personnel costs over the decades-long lifetimes of these machines.

In view of this conclusion, the committee here reiterates a recommendation from Chapter 1 of this report, concerning NMR.

Key Recommendation 3: Within the next 2–3 years, the United States should implement the installation of multiple commercially made nuclear magnetic resonance instruments with magnetic fields in the 1.0–1.2 GHz range, covering all applications from physics and materials through pharma and biophysics and onto microimaging and provide user access to these systems in the democratized science model followed by other national facilities. Such instruments should build on existing infrastructures, by relying on centers that have laid out management plans and proven track records of service to the scientific and industrial communities at large.

Achieving this will require locating instruments at a variety of sites in the United States, preferably sites that have active local user communities and adequate staffing and engineering resources to keep the facilities running at a high level for many years. Institutions that receive federal funding for such NMR instruments should be required to set aside 30–50 percent of the instrument time for outside users from academia and industry. In return, federal agencies should contribute

to staffing, maintenance, and operation costs every year. A consortium structure, where institutions with these instruments share expertise, and coordinate their efforts and decisions in a way that maximizes their combined impact, could be envisioned. Twelve such instruments would bring high-field NMR instrumentation in the United States to approximately the same level as instrumentation in Europe. Support for ancillary equipment, including high-field dynamic nuclear polarization instrumentation, associated research supplies, and helium recycling systems should also be expanded.

The committee proposes here that the facilities that would receive the new 1–1.2 GHz NMR instruments would form a network with the NHMFL high-magnetic-field laboratory and receive funds for operation and maintenance. Scientists would have access to these facilities free of charge after their proposals are positively evaluated.

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONSHIPS

The development in the high magnetic field relies on the scientific relationship and collaboration of the United States with the scientific high-magnetic-field community worldwide. This includes joint experiments and technology developments with international scientists as well as recruitment of international students, scientists, and faculty in from counties outside of the United States to work on high-magnetic-field scientific discoveries in the United States. The equal treatment of these students and scientists concerning access to high-magnetic-field facilities is critical for the field. Furthermore, U.S. scientists currently experience equal treatment concerning access to many HMF facilities outside the United States, and the committee recommends that the high-magnetic-field facilities and instrument in the United States should therefore also be open for access for scientists from outside the United States (as is the current model).

The committee is aware of the fact that security and international competition are also critical factors in the development of international relationships in the high magnetic field.7

Recommendation 8-1: It is critical that U.S. funding agencies (National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, Department of Energy, and Department of Defense) and national laboratories develop a strategic plan for balancing national security and proliferation concerns with the need for

___________________

7 White House, 1985, “National Security Decision Directive 189: National Policy on the Transfer of Scientific, Technical and Engineering Information,” https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nsdd/nsdd-189.pdf;R. Chalk, 1986, “Continuing Debate Over Science and Secrecy,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist 42:3, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.1986.11459335. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6876346.

openness and accessibility of U.S. facilities, national laboratories, academia, as well as for the private sector to international collaborators.

DEVELOPMENT OF MAGNETS IN THE UNITED STATES

It is very important to foster the development of new magnet technology in the United States, which is essential for the competitiveness of the United States in many fields that require high-field magnets, including but not limited to X-ray accelerator and XFEL technology, high-field MRI and NMR as well as fusion technology. Here the committee recommends an integrative concept where NSF and DOE jointly support a consortium for new magnet development where industry partners and academia work together on a time frame for 10 years on novel technology development to bring it to a stage that will make it profitable for the industry partners for commercialization. Concepts for such consortia already exist for other fields including the development of novel drugs by the Chemical Biology Consortium of the National Cancer Institute. The recently launched MagCorp cited next to NHMFL, could provide a good example of such private–public partnerships.8

Recommendation 8-2: The National Science Foundation and Department of Energy should jointly support a public–private partnership for new magnet development where industry partners, academia, and national laboratories work together on a time frame for 10 years on novel technology development to bring it to a stage that will make it profitable for the industry partners for commercialization.

PRINCIPLES OF FINDABILITY, ACCESSIBILITY, INTEROPERABILITY, AND REUSABILITY OF HIGH-MAGNETIC-FIELD SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DATA

The FAIR principles are requirements for all federal grants (that then give responsibilities to the PI), and they are embodied in the operations of the national user facilities. The committee believes that the principles are being adequately upheld by current arrangements.

___________________

8 Magnetics Corporation, “Bringing Superconducting Technologies to the World,” https://magneticscorp.com, accessed June 27, 2024.