The Current Status and Future Direction of High-Magnetic-Field Science and Technology in the United States (2024)

Chapter: 6 Superconducting Materials and Wires/Tapes for High-Field Magnets

6

Superconducting Materials and Wires/Tapes for High-Field Magnets

INTRODUCTION

There are currently several superconducting materials used for design and fabrication of high-field magnets.1 The most widely established of them—low-temperature superconductor NbTi—is the workhorse material for all types of high-field magnets. In the past 50 years, tens of thousands of NbTi-based magnets have been built and successfully deployed worldwide. These magnets are utilized in clinical medicine and various fields of scientific and technical research. It is important to emphasize that this successful deployment is the result of significant investments, by U.S. government agencies, in material science and engineering research and development (R&D) projects that established the basis for the “magnet production ready” NbTi wire.2 Developments in the performance improvements of NbTi wire continue, but it is mostly related to incremental enhancements in the low-field, high-critical-current mode of operation. If, however, the push toward stronger magnets and higher magnetic fields can continue the opportunities in a wide set of areas can get closer to realization, such as: compact fusion devices, next

___________________

1 L. Cooley K. Amm, W. Hischier, S. Rotkoff, and D. Larbalestier, 2023, “Business Models to Ensure Availability of Advanced Superconductors for the Accelerator Sector and Promote Stewardship of Superconducting Magnet Technology for the US Economy,” Report sponsored by the Department of Energy’s Office of Accelerator Research Development and Production.

2 P.J. Lee and B. Strauss, 2011, 100 Years of Superconductivity, H. Rogalla, and P.H. Kes, eds., Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, https://fs.magnet.fsu.edu/~lee/superconductor-history_files/Centennial_Supplemental/11_2_Nb-Ti_from_beginnings_to_perfection-fullreferences.pdf.

generation magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ubiquitous nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

Another material—low-temperature superconductor Nb3Sn—is an alternative to NbTi when a higher (about 1.5 times) field is desired. Although this material was discovered before NbTi, its utilization for high-field magnets was significantly slower. Such a delay was owing to the complexity of the fabrication and handling of Nb3Sn-based magnets, and because for quite a while the marketplace for industrial and scientific applications was content with NbTi-based magnets. However, the path from R&D of the Nb3Sn superconductor to its deployment in the fabrication of first magnets and then wider use in scientific and other applications is similar to, although longer than, the one for NbTi. This path includes (a) sustained, multi-year investments by U.S. government agencies in R&D programs for material science and magnet prototyping programs, (b) construction and operation of high-field Nb3Sn magnets, and (c) successful public–private partnerships that demonstrate technical and economic viability of different types of Nb3Sn superconducting (SC) magnets. But unlike NbTi, the development of more advanced Nb3Sn wire and Nb3Sn-based magnets are far from the finish line, as their performance can still be noticeably improved. As of today, Nb3Sn is the material of choice for NMR magnets, and it was also chosen to produce toroidal field and central solenoid coil magnets for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER). There are several very high-field—10 Tesla (T) and above—SC magnets around the world that are using Nb3Sn magnet coils. These magnets were pioneered in the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL). Recently the first Nb3Sn-based accelerator magnets have been built for and delivered to the High Luminosity Large Hadron Collider (HL-LHC). Also, the first Nb3Sn-based SC undulator was successfully operated at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Even although Nb3Sn wires and cables have begun to gain a foothold in some accelerator applications, significant effort and investments still are required for further development of this technology and the establishment of a competitive and reliable marketplace.

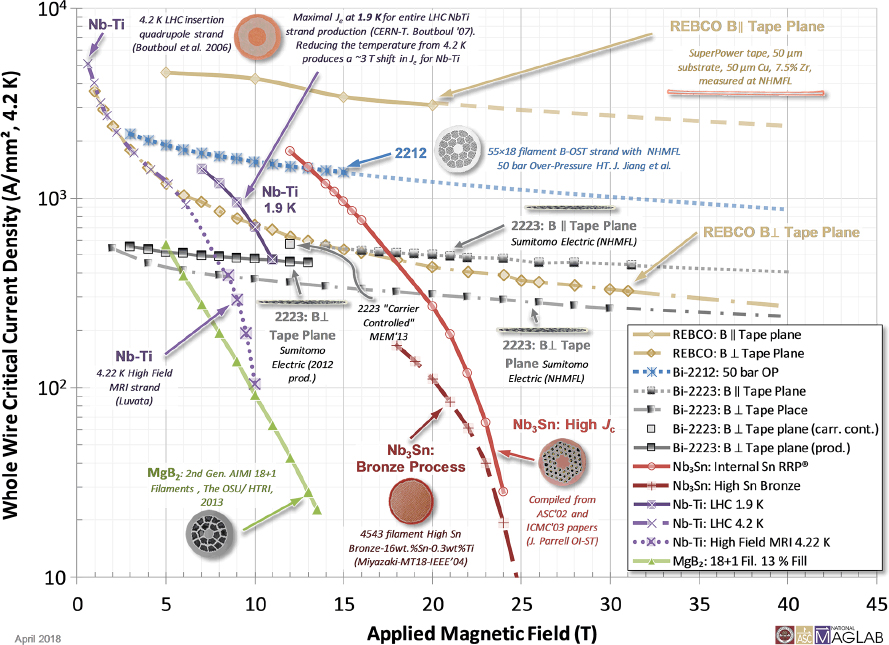

Two other materials—Bi2Sr2CaCu2Oy (Bi2212) and REBa2Cu3Oy (REBCO, RE: rare-earth element or Y)—represent high-temperature superconductors (HTS). As shown in Figure 6-1, both materials are capable of transporting noticeably higher current density compared to NbTi or Nb3Sn at high field.

Bi2212 round wire and REBCO tape are manufactured by several companies in the United States, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and China. There are active R&D programs in all these countries to support the material science of these materials and the wire and tape production engineering. The Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) support such programs in the United States. The most notable achievements in the utilization of HTS materials are in the design and construction of HTS inserts for hybrid high-field magnets

SOURCES: Edited from the compilation plot provided courtesy of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. Original data sources can be found at Plots - MagLab (nationalmaglab.org).

and prototype magnet for industrial tokamak projects. There are several other existing HTS materials that were or could be used for the design and construction of high-field magnets, but applications for such purposes are currently limited and the prognosis for their wide use is uncertain at best. For example, iron-based superconductors ([Ba, AM]Fe2As2 [Ba122], AM: alkali metal) tapes and wires are under development by Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Circuits and Systems Society (IEEE-CAS), China. High-engineering (full wire) current density and multifilament configurations need to be demonstrated. Bi2Sr2Ca2Cu3Oy (Bi2223) tape was commercially available and some high-field magnets and applications with Bi2223 tapes have been developed in Japan and New Zealand. But owing to the low market demand Sumitomo Electric Industrial stopped the production of Bi2223 tapes in 2024.

SUPERCONDUCTORS: STATUS AND DEVELOPMENTS

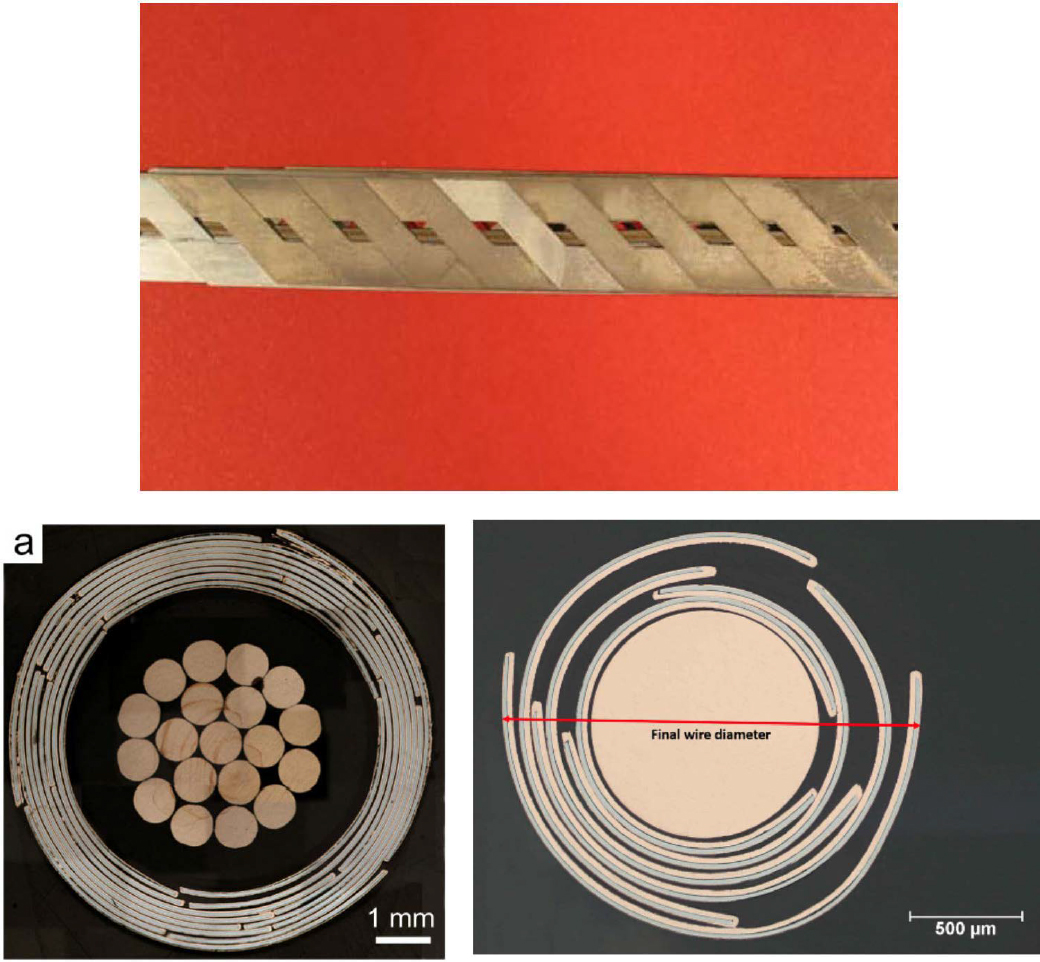

The superconducting alloy NbTi was discovered in the early 1960s. In the subsequent two decades, driven mostly by the needs of high-energy particle accelerators, NbTi wire technology was developed. The wire fabrication technology was pioneered in the United Kingdom and was quickly adopted and advanced in the United States and elsewhere. The cross section of a typical NbTi wire is shown in Figure 6-2.

NbTi filaments (as many as 105) are imbedded in a Cu matrix. The wire diameter can be from 0.1 mm to 3 mm, while the filament diameter can vary between 5 μm and 50 μm. The length of the wire can reach several kilometers, and wire strands can be combined into one multi-wire cable. The NbTi wire is manufactured using a stacking, co-drawing, and extrusion process with intermediate heat treatment. The development of the wire fabrication technology was supported through R&D programs of U.S. government agencies. These programs included design and tests of various prototype magnets. The magnets’ technical specifications and actual performance provided the feedback loop for improvements of the wire manufacturing process that resulted in the fabrication of operationally stable, uniform, and quite long NbTi SC wire, and later, cables built from this wire. The first large batch of high-quality, high-performance NbTi wire/cable, about 17 tons, was produced in the late 1970s for the construction of the Tevatron at FNAL, and another large quantity of wire for construction of Isabelle at BNL. This wire production was the result of a very strong and close partnership between DOE labs and SC wire manufacturers in the United States and Europe. An amount of NbTi wire comparable to that for the Tevatron was also produced for the high-energy electron-positron

SOURCE: Courtesy of Alexander Zlobin, Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

collider HERA in Germany.3 The development of high quality NbTi wire and the stable operation of accelerator SC magnets benefitted the emerging market of MRI instruments. The technical requirements for the MRI magnets’ NbTi wire were more relaxed compared to accelerator magnets. It made the manufacture of the wire more affordable while still achieving a field up to 3 T. Currently the annual production of NbTi wire in the world is measured in hundreds of tons, and the production of MRI instruments drives this number. There are multiple stable suppliers of NbTi wire around the globe. But all of them depend heavily on a quite limited number of suppliers of Nb. CBMM is by far the world’s largest producer of niobium metal and its alloys, providing more than 80 percent of the world’s supply.4 The R&D effort in the performance improvement of NbTi wire is limited. It is accepted that in the high-field region NbTi wire performs very close to its theoretical limit. And although some incremental advancements in NbTi wire performance could be made for some special magnets operated with low-field, high-critical current, these small improvements could benefit only a very limited number of magnet developers and users.

Finding: NbTi wires are widely used for MRI and NMR and accelerators. The supply chains and those performances look good enough.

An intermetallic composite, Nb3Sn, was discovered as a superconductor in 1954.5 It took quite some time to develop the wire fabrication method for this material. There are currently three methods of fabricating Nb3Sn wire (i.e., bronze route, internal-Sn, and powder-in-tube [PIT]). All these methods resulted from many years of detailed material science studies of Nb3Sn and from the wire fabrication techniques developed earlier for NbTi wire. The cross section of Nb3Sn wire is shown in Figure 6-2. The wire diameter can vary between 0.5 mm and 1 mm, and filaments can be as small as 5 μm in diameter depending on the fabrication techniques. The length of the wire can be several kilometers, and wire strands can be assembled in multi-wire cable, the same way as for NbTi cable, but the heat-treatment for Nb3Sn reaction is necessary after the cabling and the winding as mentioned later. Two of the three fabrication methods deliver Nb3Sn wire with high-critical current. The main difference between these two methods is in the way, and in what shape, components of the composite, Nb and Sn, are placed

___________________

3 D. Barber, R. Kose, R. Brinkmann, et al., 1986, Reports at the 13th International Accelerator Conference, Novosibirsk, USSR, August 7–11, 1986.

4 D. Alvarenga, 2013, “ ‘Monopólio’ brasileiro do nióbio gera cobiça mundial, controvérsia e mitos,” Globo, https://g1.globo.com/economia/negocios/noticia/2013/04/monopolio-brasileiro-do-niobio-gera-cobica-mundial-controversia-e-mitos.html.

5 B.T. Matthias, T.H. Geballe, S. Geller, and E. Corenzwit, 1954, “Superconductivity of Nb3Sn,” Physical Review 95(6):1435.

in the Cu matrix. The existing options include rod and tube shape for Nb or Nb alloy, and solid for Sn or Nb-Sn powder. Rod and restack process (RRP; one of the internal-Sn methods) and PIT methods can produce high Jc wires (>1,000 A/mm2 at 15 T, 4.2 K). The Jc of bronze route Nb3Sn wires is almost half of the RRP one and limited by the solubility limit of Sn in Cu. However, this process can be used to produce thin Nb3Sn filaments approximately a few microns in diameter. The extrusion, draw, and stacking in general are like the fabrication of NbTi wire. But unlike NbTi wire, which is “ready to use SC,” Nb3Sn wire must go through a high temperature, above 600°C, chemical reaction to become a superconductor. A reaction sequence produces Cu-Sn phases at temperatures below 600°C, and then at higher temperatures a diffusion reaction between Cu-Sn and Nb takes place in the case of the internal-Sn methods. At this final stage Nb3Sn SC is formed. After the reaction is complete, Nb3Sn wire becomes very brittle; Nb3Sn SC coils require cautious handling and cannot be unwound from the magnet’s core and repaired. Therefore, the heat-treatment after the coil fabrication (wind-and-react method [W&R]) is typically used for Nb3Sn coils. Also, high temperature and long reaction time limits the choice of materials for the wire insulation and overall magnet designs. Figure 6-3 shows that Nb3Sn has noticeably higher-critical current and therefore could be used to build magnets with higher field than identical NbTi-based magnets. Similar to the case of NbTi, the development of the first operational Nb3Sn-based high-field magnets made an impact on other research and technical fields. Specifically, it led to the design and construction of most advanced NMR magnets with a field above 20 T. Also, several Nb3Sn and hybrid (Nb3Sn plus other wire) magnets have been built and currently operate in different research institutions, including BNL, FNAL, and NHMFL in the United States.6 Recently, the very first large Nb3Sn accelerator magnets have been built in a multi-lab collaboration between FNAL, BNL, and LBNL and delivered to the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) for the HL-LHC project. As it was for NbTi wire, the successful development and deployment of operational Nb3Sn magnets would not have been possible without sustained decades of support through DOE and NSF programs and the strong cooperation between the research institutions of both agencies and U.S. universities. This support is as critical today as it was through all the previous years. The performance of Nb3Sn wire and Nb3Sn-based magnets can be improved. New advanced Nb alloys, artificial pinning methods,7 addition

___________________

6 Many institutions and universities use commercial high field magnets by several magnet companies (Oxford Instruments, Cryogenics, Cryomagnetics, JASEC, and so on) above 10 T for research.

7 X. Xu, P. Li, A.V. Zlobin, and X. Peng, 2018, “Improvement of Stability of Nb3Sn Superconductors by Introducing High Specific Heat Substances,” Superconductor Science and Technology 31(3):03LT02.

of high specific heat capacity materials,8 and a decrease of filament diameter could lead to improved wire performance. Some high-strength Nb3Sn wires and cables have been successfully produced, for instance, the large bore CuNb/Nb3Sn Rutherford cable magnet for the 25 T cryogen-free superconducting magnet is used under a high stress of 260 MPa and a conduction cooled condition for more than 8 years. The high strength Nb3Sn wires and cables enable the coil winding after heat-treatment (react-and-wind [R&W]). Further advancements will likely not be driven by industry; therefore, funding through the dedicated government agencies via R&D and technology transfer programs is required. It is also important to note that unlike the NbTi case, there are very few manufacturers of Nb3Sn wire in the world, and this wire is several times more expensive than NbTi.

Finding: Cu/Nb3Sn wires are widely used for high-field applications. ITER drives the Nb3Sn wire and conductor development. The bronze (Bz)-route and internal-Sn (Int-Sn) route exist for the practical applications. Non Cu Jc in the Bz-Nb3Sn looks spatulated because of a solubility limit of Sn in the bronze. The improvement of non Cu Jc is mainly on-going with the Int-Sn-Nb3Sn wire under the strong requirements from CERN for the Future Circular Collider (FCC). Some R&D conductors with a rod and restack process (RRP) in Bruker, and PIT combined with Artificial Pinning Center in collaboration between FNAL, Hypertech Research Incorporated, and Ohio State University, met the FCC requirements of 1500 A/mm2 at 16 T and 4.2 K.9 The Jc improvements based on Int-Sn method in the other companies are under development. JASTEC recently succeeded in the 1100 A/mm2 with a distributed-Sn method. Most of Nb3Sn wires are produced in the European Union and Asia. Especially, high Jc Nb3Sn wires can be produced only by Bruker.

A new class of superconductors—HTS—promises, as shown in Figure 6-1, to outperform NbTi and Nb3Sn at high-fields. Their high critical temperatures could also be leveraged for higher temperature operation. One of two practical HTS’s—Bi2212 (Bi2Sr2CaCu2O10)—is produced as a multifilament round wire (see Figure 6-2, bottom right). Many fabrication techniques developed for NbTi and Nb3Sn wire and cable can be applied to Bi2212. Currently, the annual Bi2212 wire production amounts to less than 1 ton. For the Bi2212 material to become a superconductor, it must be brought up to almost 900°C in an Argon and O2 atmosphere under

___________________

8 Z. Xu, Q. Zhang, F. Fan, L. Gu, and Y. Ma, 2019, “C-Axis Superconducting Performance Enhancement in Co-Doped Ba122 Thin Films by an Artificial Pinning Center Design,” Superconductor Science and Technology 32(12):125014.

9 X. Xu, M. Sumption, F. Wan, X. Peng, J. Rochester, and E. Choi, 2023, “Significant Reduction in the Low-Field Magnetization of Nb3Sn Superconducting Strands Using the Internal Oxidation APC Approach,” Superconductor Science and Technology 36:085008.

SOURCE: S. Awaji, 2019, “Superconductors in High Magnetic Fields—Now and the Future,” IEEE CSC and ESAS Superconductivity News Forum, plenary presentation 3-MO-PL2. Courtesy of Satoshi Awaji.

50 bar pressure. As with Nb3Sn magnets, construction of Bi2212 magnets utilizes the W&R approach. Quite high reaction temperature limits the choice of materials for this magnet design and fabrication, even more than for Nb3Sn magnets. Furthermore, owing to the high pressure and high temperature, with high-precision temperature control, today reaction of large coils is a major technological challenge. A high-pressure large furnace is an additional complication and cost of the fabrication. The DOE and NSF have supported the development of the Bi2212 conductor and magnet coils over the last 15 years. Teams from U.S. national labs, universities, and NHMFL collaborated in several projects that led to demonstrations of good reproducibility of coil reactions. The Bi2212 large solenoid coil successfully generated 5.9 T in a 12 T background field.10 There are two laboratory solenoid magnets with Bi2212 inserts currently under construction at NHMFL for >25 T NMR and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) applications. Bi2212 accelerator dipole magnet development is also ongoing as part of the U.S. Magnet Development Program. Several small demonstrators, using Bi2212 Rutherford cables, are under development along with plans to test these under background fields in a hybrid LTS and HTS configuration.

Finding: Bi2212 is a promising technology for high-field magnets. There have been impressive advances in the current carrying capacity of the conductor over the past decade. The round wire geometry makes it desirable for many magnet applications. The primary challenges in using this technology are related to the high temperature and pressure heat treatment that is required to form the superconductor as well as the brittle nature of the superconductor. There does not seem to be a large market for Bi2212 to drive its development at the moment.

Bi2223 is another superconductor that has been applied in magnet technologies. The Sumitomo Electric Industry (SEI) Ag/Bi2223 tapes have high Jc and high strength. One operational high-field magnet with a Bi2223 insert and Nb3Sn and NbTi outer coils was constructed by Toshiba and Tohoku University in 2017. Ni-alloy/Ag/Bi2223 tapes (HT-Nx) have been used for a part of (cryogen-free) high-field magnets such as a 25 T cryogen-free superconducting magnet, which has operated for more than 8 years as a user magnet.11 Unfortunately, SEI stopped the production of Bi2223 in 2024.

___________________

10 National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 2024, “An R&D Milestone for Bi-2212 High Temperature Superconducting Magnets,” https://nationalmaglab.org/magnet-development/appliedsuperconductivity-center/research/science-highlights/a-new-mark-for-bi-2212-all-superconducting-magnets.

11 S. Awaji, K. Watanabe, H. Oguro, et al., 2017, “First Performance Test of a 25 T Cryogen-Free Superconducting Magnet,” Superconductor Science and Technology 30(6):065001.

Another practical HTS material is REBCO; RE1Ba2Cu3O7, where RE stands for Y or a rare-earth element; it is also called 2G-HTS CC. The development of REBCO material for industrial use, such as electric power applications, started around 1990 in the United States. It was supported by the DOE Office of Electricity. The main goal was the development of technology for manufacturing HTS electric cables. The program demonstrated significant advances in the fabrication of HTS conductors, some of them a kilometer long. But in 2010, owing to lack of commercial pull by U.S. utilities, this program was terminated. All HTS scientific and industrial efforts have been reoriented toward the conventional application of superconductors—the generation of high magnetic field. A similar program began in 2000 in Japan. A new U.S. program, funded by DOE HEP and NSF, united teams from several universities and national labs. The main goal was to develop the technology to fabricate REBCO material that can achieve a record-high critical current in a record-high upper-critical field. The success of this program led to the design and construction of high-field hybrid solenoid magnets with inserts built from REBCO. A world record of 45.5 T under 31 T background field has been achieved with the LBC-stacked pancake magnet.12 The program in Japan, China, and France also resulted in successful construction of REBCO-based high-field magnets at 31.4 T.13

The majority of REBCO superconductors are currently fabricated as tapes. The tape can be from 4 mm to 12 mm wide and 0.1 mm to 0.2 mm thick. The schematic diagram of the REBCO tape structure is shown in Figure 6-4. The thickest part of the tape consists of the Hastelloy substrate made of Ni-W-based alloy and Cu. The mechanical properties of the substrate define most of the limits for using REBCO tape for magnet winding. The HTS layer, which is only 1 to 2 μm thick and represents only 1 percent of the total tape thickness, can be deposited on the tape by two methods. In one method laser pulses irradiate the target with HTS material and excited deposition seeds land on the tape substrate. The process takes place in a vacuum. A second method utilizes a metal organic chemical vapor deposition technique. Both methods succeeded in producing high critical current HTS tapes. There are several manufacturers of HTS tape in the world: in the United States,

___________________

12 S. Hahn, K. Kim, K. Kim, et al., 2019, “45.5-Tesla Direct-Current Magnetic Field Generated with a High-Temperature Superconducting Magnet,” Nature 570(7762):496–499.

13 Y. Suetomi, T. Yoshida, S. Takahashi, et al., 2021, “Quench and Self-Protecting Behaviour of an Intra-Layer No-Insulation (LNI) REBCO Coil at 31.4 T,” Superconductor Science and Technology 34(6):064003; J. Liu, Q. Wang, L. Qin, et al., 2020, “World Record 32.35 Tesla Direct-Current Magnetic Field Generated with an All-Superconducting Magnet,” Superconductor Science and Technology 33(3):03LT01; P. Fazilleau, X. Chaud, F. Debray, T. Lecrevisse, and J.-B. Song, 2020, “38 mm Diameter Cold Bore Metal-as-Insulation HTS Insert Reached 32.5 T in a Background Magnetic Field Generated by Resistive Magnet,” Cryogenics 106:103053.

SOURCES: Top: W. Goldacker, R. Nast, G. Kotzyba, et al., 2006, “High Current DyBCO-ROEBEL Assembled Coated Conductor (RACC),” Journal of Physics: Conference Series 43(1):901–904, https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/43/1/220. © 2006 IOP Publishing Ltd. CC BY-NC-SA. Bottom left: Used with permission of IOP Publishing, Ltd., from D.C. Van Der Laan, X.F. Lu, and L.F. Goodrich, 2011, “Compact GdBa2Cu3O7−δ Coated Conductor Cables for Electric Power Transmission and Magnet Applications,” Superconductor Science and Technology 24(4); permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. Bottom right: Used with permission of IOP Publishing, Ltd., from S. Kar, W. Luo, A. Ben Yahia, X. Li, G. Majkic, and V. Selvamanickam, 2018, “Symmetric Tape Round REBCO Wire with Je (4.2 K, 15 T) Beyond 450 A mm–2 at 15 mm Bend Radius: A Viable Candidate for Future Compact Accelerator Magnet Applications,” Superconductor Science and Technology 31(4):04LT01, https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6668/aab293, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Japan, Europe, South Korea, and China. All of them are capable of manufacturing kilometer-long REBCO tapes. Some of the manufacturers also have a large production capacity of more than 1,000 km/year. The production is primarily driven by advanced fusion applications.14 Because of the monofilament tape structure in REBCO cable-in-conduit, the inhomogeneity in the tape’s geometry, critical current density, Cu stabilizer quality, and mechanical properties are issues for applications. Quality assessments and analyses are also needed.

Finding: REBCO conductors have advanced significantly and can provide high-current densities at high field. Fusion advances are the main driver for the scale-up of production of REBCO. MRI and NMR applications are currently not a main driver for REBCO scale-up even although it may be used on a few research systems. The current cost of the conductor is high and widespread availability is low, but the production needs from fusion work could potentially reduce the cost and make the conductor available for other users.

Conclusion: Test facilities, which are essential for characterizing HTS strands and cables at high current and high background fields, are limited today. The new U.S. facility that is being developed at FNAL as a collaboration between HEP and FES will be a welcomed addition.

One of the primary challenges related to incorporating REBCO into different types of magnets is the tape geometry. Round and isotropic wires have advantages in terms of fabrication and operation for many magnet applications when compared to the flat and highly mechanically and electrically anisotropic REBCO tapes. Furthermore, fusion and accelerator magnets, among others, require high-current conductors (typically composed of many individual strands). The primary reason for this is to keep quenching voltages within reason.15 Furthermore, cables composed of transposed or twisted strands can be used to reduce AC losses and improve stability through current sharing. For REBCO, this requires that individual tapes be bundled into twisted/transposed high current wires or cables. For accelerator magnets, several such concepts and products exist for this, for example:

___________________

14 A. Molodyk, S. Samoilenkov, A. Markelov, et al., 2021, “Development and Large Volume Production of Extremely High Current Density YBa2Cu3O7 Superconducting Wires for Fusion,” Scientific Reports 11(2084).

15 M. Wilson, 1983, Superconducting Magnets, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roebel cables,16 CORC cables and wires,17 as seen in Figure 6-4, and STAR wires.18 Although there is clear progress in these areas, significant work is still required for broad application of these conductors. For example, improvements in reduction of bending radius, improved current sharing, and improved reliability and uniformity of the tapes are desirable. From the mechanical standpoint, improved delamination strength and improved compatibility with impregnation materials is also desirable. Other challenges requiring further investment include understanding and mitigation of large screening currents in the tape, which can induce magnetic field errors and large stresses; improvement in the Jc homogeneity in the REBCO tapes; and improved control of thickness and Residual-Resistance Ratio. Quality assessments and control are also required in commercialized REBCO wires, especially at low temperature.

Conclusion: For HTS conductors to be applied broadly in the high-field magnet area, many evolutionary steps must be completed. This process can take many millions of dollars over decades.

HIGH STRENGTH CONDUCTOR FOR PULSED MAGNETS

Copper Niobium (Cu:Nb) nanostructured high strength and high conductivity wire has proven to be a key element to success for the U.S.-based, high-magnetic-field generation endeavors utilizing pulsed methods. The highest strain regions of NHMFL’s 100 T multi-shot magnet is in the innermost layers with peak stress occurring around layer 3 or 4 of the insert coil. Like many extremely high-field pulsed magnets this magnet manages the stress distribution through the engineering and design of multi-layer and multi-material composite structures. Nondestructive pulsed magnets must handle extreme radial and axial forces in a dynamic environment. The strain fields are proportional to the time duration of the pulse which is often designed to be as quick as possible to avoid excessive Joule heating from high currents (~30–60 kA) while long enough in duration to minimize eddy current heating in the material samples under study and allow for good signal integration that permits high quality data (pulse risetimes of ~5–20 milli-seconds is ideal). The

___________________

16 W. Goldacker, R. Nast, G. Kotzyba, et al., 2006, “High Current DyBCO-ROEBEL Assembled Coated Conductor (RACC),” Journal of Physics: Conference Series.

17 D.C. van der Laan, X.F. Lu, and L.F. Goodrich, 2011, “Compact GdBa2Cu3O7–δ Coated Conductor Cables for Electric Power Transmission and Magnet Applications,” Superconductor Science and Technology 24(4):042001.

18 S. Kar, W. Luo, A.B. Yahia, X. Li, G. Majkic, and V. Selvamanickam, 2018, “Symmetric Tape Round REBCO Wire with Je (4.2 K, 15 T) Beyond 450 A mm−2 at 15 mm Bend Radius: A Viable Candidate for Future Compact Accelerator Magnet Applications,” Superconductor Science and Technology 31(4):04LT01.

present state-of-the-art CuNb has an ultimate tensile strength of approximately 1,400 MPa and an electrical conductivity of approximately 90 percent relative to copper. Cu:Nb magnet wire with these characteristics has been used by NHMFL for the inner regions of the 100 T multi-shot magnet and it was procured from a vendor in Russia (Rusnano).

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The current investment in REBCO is tightly focused on fusion applications. Other communities, except for a relatively small investment in BSCCO, are depending on the fusion wire investments for the advancement of these conductors. However, the requirements for HTS wire for the fusion community are largely focused on the amount/length of wire that is necessary, resulting in a large investment in manufacturing techniques suitable for their specific type of wire need. For example, the geometry of the conductor may need to be optimized for the specific application, driven by specific requirements on current requirements, minimum bending radius requirements, and materials and voltage considerations. Furthermore, joint technology could have significantly different requirements dependent on the application. All these features must then be integrated into a design for the magnet, which considers structural specifications, insulation, field distribution, and transient effects across the system.

Development through these issues can be loosely described as movement through the Technology Readiness Levels. Importantly, the various types of magnets all have distinct requirements. While investments in research often can be performed with little funds (such as high Jc in a small section of tape) and can enable future products, as a rule it is by far more expensive by orders of magnitude to bring a research breakthrough to fruition. This reality is commonly called the “Valley of Death” for technology development.

HTS conductors will bring revolutionary change in many different applications in the magnet realm alone. Leadership in high-magnetic-field science in the next decades will involve the mastery of the use of HTS materials in various applications. While the private investments currently being made for plasma fusion, in the case of REBCO, may be enabling. They will not, however, meet the needs of the other high-magnetic-field applications of REBCO wire owing to the nature of technology development.

Development of HTS is critical for future high-field magnets, and early and significant investment is needed to develop the technology to a sufficient level for more widespread use (by reducing cost and improving quality). There is a need for investment at an R&D level (universities and laboratories) that can be transferred to industry for production scaleup. For magnet development, it is essential that

material is available for R&D demonstrators. Sufficient cost decreases will need more than a scaleup in equipment, it will also need technological advances.

Key Recommendation 1: The National Science Foundation and Department of Energy are urged to double their support for the development of wire technologies within 2–3 years, including support to re-establish the U.S. high-temperature superconductor (HTS) wire industry and the establishment of U.S. test facilities appropriate for characterizing HTS conductors and cables at high field and stress. This should focus at both the fundamental level (universities and laboratories) and production level (industry).

Recommendation 6-1: U.S. industry needs to increase its capacity to produce wire within the next 3–5 years to support the expected demand from magnet production and fusion efforts.