Newborn Screening in the United States: A Vision for Sustaining and Advancing Excellence (2025)

Chapter: Summary

Summary1

Newborn screening (NBS) is a public health service available to approximately 3.6 million infants born in the United States each year. Over 98 percent of those infants receive screening. State and territorial-run NBS programs identify babies at risk of serious but treatable conditions and connect them to a provider for confirmatory testing, treatment, and follow-up care with the goal of providing the best chance at a healthy life. Newborn screening encompasses dried blood spot, hearing loss, and congenital heart defect testing; however, the focus of this report is dried blood spot screening in the United States. The public health impacts of dried blood spot newborn screening are felt across society but perhaps most profoundly by the over 7,000 infants identified annually for timely intervention, along with their families and caregivers. Public health newborn screening is implemented through 56 state- and territorial-run programs and buttressed by the contributions of multiple federal agencies, laboratory and clinical professional communities, health care providers, patient advocacy groups, researchers from academia and industry, and others.

Public health newborn screening faces both longstanding and emerging challenges. Processes for adding conditions to the federal Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) and state and territorial NBS panels have come under scrutiny for their limited capacity to keep pace

___________________

1 This summary does not include reference citations. References for the information herein are provided in the full report.

with therapeutic developments, and for the burden these processes place on patient advocacy communities and others. NBS programs and professionals need to maintain high-quality services in a resource-constrained environment as screening panels expand. The potential use of genomic sequencing in newborn screening raises scientific and technical questions, as well as social, ethical, legal, and policy questions, including privacy concerns over genomic data. Legal challenges over retaining and reusing residual dried blood spots have led to the destruction of millions of specimens. Ultimately, public health NBS programs must balance their mandate to screen all newborns with the individual needs and rights of each child and their family.

Public health newborn screening also contends with multiple dimensions of variability. Although differences across NBS programs are inevitable and may even be beneficial, variability can be detrimental when driven by insufficient resources or when it negatively affects health outcomes. Insufficient representation of genetic ancestries in databases results in higher rates of false positives and negatives on DNA-based screening assays for infants of non-European descent. Infants from underserved communities experience longer wait times to confirmatory diagnosis and treatment. Issues facing the NBS system intersect with longstanding disparities in the health care system, such as uneven distribution of specialists and differences in insurance coverage or access to new therapies. Although not within the purview of public health newborn screening to address, this landscape impacts the effectiveness of this service in fulfilling its mission.

IMPETUS FOR THE STUDY

Newborn screening as a public heath endeavor is asked to address a complex array of needs, competing priorities, and viewpoints. In response to a congressional request, the Office on Women’s Health of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to convene an ad hoc committee to examine the current landscape of newborn screening implementation and research in the United States, recommend options to strengthen public health newborn screening, and establish a vision for the future.2

The committee prioritized its efforts toward developing a longer-term vision for newborn screening and a road map to achieve it, recognizing ongoing efforts by federal agencies, state and territorial programs, and

___________________

2 Reflecting the complexity of its task, the committee included members with expertise in newborn screening, state and federal public health, lived and parental experience, bioethics and law, existing and emerging screening technologies, health systems, health economics, and clinical care disciplines.

others to address immediate problems within the existing NBS framework. Central to the committee’s approach was input from individuals personally and professionally affected by newborn screening. With additional support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the committee commissioned civic engagement consultants, together with National Academies staff, to hear from multiple sectors of lived and professional experience in newborn screening. The report was also informed by presentations from speakers, published literature, and other sources of evidence.

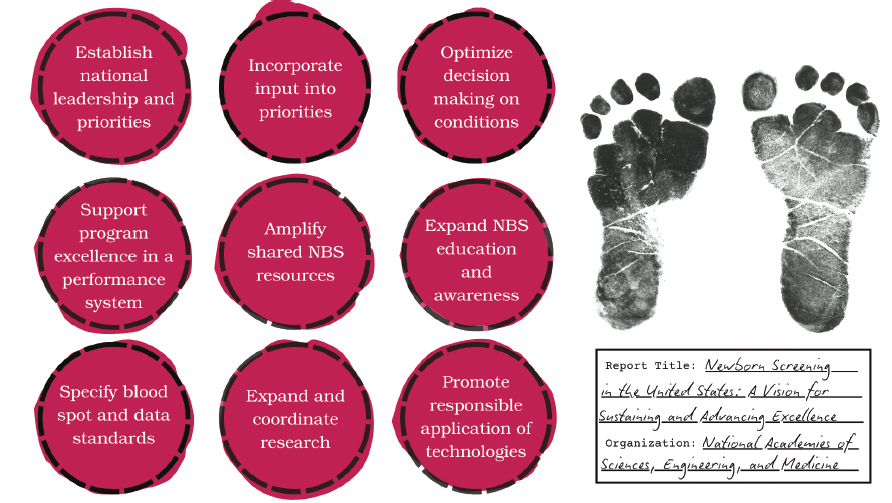

A ROAD MAP FOR EXCELLENCE IN NEWBORN SCREENING3

A central tenet of this report is that a systematic and coordinated approach for public health newborn screening is needed—one that aligns multiple critical partners around shared goals, builds on and enhances connections among the array of efforts and programs already in place, clarifies essential functions and responsibilities, and supports public health NBS excellence now and into the future. The following recommendations reflect priorities to achieve these aims and identify core actors to champion each one within a holistic vision (see Box S-1). Collectively, the recommendations outline a path to navigate the choices facing dried blood spot newborn screening in the United States while preserving and enhancing what is already considered a valuable and effective public health achievement.

The mission of public health newborn screening is to reduce morbidity and mortality for identified infants, and NBS programs are responsible for detecting and connecting those infants with clinical care. Aligning with this mission entails a focus on conditions that are serious, urgent, and have a therapeutic intervention rigorously shown to reduce morbidity and/or mortality in affected infants when delivered in the presymptomatic or early symptomatic period. Public health newborn screening has faced pressures to expand its scope to include conditions that are, for example, later onset or have no available treatment, and to consider benefits beyond reducing morbidity and mortality in the affected infant. However, the parameters guiding routine, universal newborn screening as a public health program are necessarily narrow because of its population-level nature.

Public health newborn screening cannot and should not be the sole or even the primary solution to broader needs in rare disease identification, diagnosis, treatment, and research or to longstanding challenges around access and capacity in the clinical care system. Complementary investments at the nexus of public health, clinical care, and research remain essential.

___________________

3 The report focuses on critical functions and actions to strengthen public health newborn screening for the future; descriptions of the roles and structures of federal and nonfederal activities relevant to newborn screening are current as of March 24, 2025.

BOX S-1

Summary of Recommendations: A Road Map Forward

Public health newborn screening requires a systems approach to align multiple parties around shared goals and opportunities. Decision making for public health newborn screening must be aligned with the purpose of universal screening to reduce morbidity and mortality for infants with serious but treatable diseases through connection to diagnosis and care. It must be evidence based as it encompasses technological and therapeutic advances, adds or removes conditions based on clear and consistent criteria, and promulgates national standards and guidance. All 56 state- and territorial-run programs must be equipped to provide excellent, high-quality services to all babies. The following near-term actions and foundational changes can prepare newborn screening for the future.

This report’s recommendations reinforce longstanding calls to address areas such as public awareness of newborn screening, program capacity, continuous quality improvement, evidence generation, and the diagnostic and care impacts experienced by patients with rare diseases, their families, and communities. Efforts supporting NBS excellence already exist among state and territorial NBS programs and state public health services; federal partners such as the Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Food and Drug Administration, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; and the HHS Advisory Committee for Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC). NBS excellence is also being

advanced through efforts among disease and community organizations, researchers, and technology developers to enhance the evidence base on which public health newborn screening relies, through professional organizations to collect and analyze data and develop and provide educational resources, and through the activities of many additional organizations and individuals. However, these efforts are subject to variable and often temporary funding, and participation is largely voluntary and ad hoc. Federal programs often require NBS program staff to identify challenges, locate prospective resources, draw on personal networks and contacts, and prepare competitive grant applications, leading to variable participation.

Achieving the report’s recommendations will require cooperative action to build on these foundations and extend them to establish a framework in which crucial partners are aligned around a set of shared priorities, supported through sufficient resources and time, and bolstered by infrastructure to support excellence consistently throughout public health newborn screening.

Establish National Vision, Coordination, and Leadership

The lack of a coordinated national approach to public health newborn screening with appropriate resources, accountability, and strategy hampers progress toward an excellent system nationwide. Those involved in newborn screening are committed to its success and work diligently within their spheres, but goals and efforts can misalign. Each of the 56 NBS programs needs to understand whether they are providing high-quality services for all babies born in their jurisdiction while lacking authority over many of their critical NBS partners and contending with varied resources and capacities. The next era of public health newborn screening needs to embrace opportunities for greater national coordination, priority setting, and guidance while leveraging and respecting the autonomy and local expertise of state- and territorial-run programs as well as the unique roles of federal agencies.

Federal leadership, accountability, resources, and coordination are needed to mobilize partners in the NBS ecosystem to implement the actions identified by the set of recommendations in this report, create intentionality within a landscape that is highly fragmented, and ultimately bring resources, authority, and capacity to the national patchwork quilt of public health newborn screening.

Recommendation 1: Establish national leadership and set priorities. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should provide unified leadership, accountability, and

coordination across government agencies, newborn screening (NBS) programs, and the broader NBS community.

- With input from partners (see Recommendation 2), HHS should establish a 10-year strategic plan based on this report’s recommendations and begin to implement them.

- HHS should designate a mechanism with appropriate authority, accountability, and resources to facilitate realization of this plan.

Newborn screening is experienced by infants and their families and carried out and supported by a large network that spans public health, clinical care, research, government, advocacy, and private companies. Achieving the report’s recommendations will also require representation from the full complement of personally and professionally affected groups to provide essential input and galvanize action. Newborn screening touches a complex nexus of federal, state, tribal, and private rights and responsibilities. Additional conversations are needed with tribal nations and leaders to understand these intersecting rights and authorities, to involve tribal communities in the national vision for newborn screening, and to ensure that priorities and solutions meet the needs of Indigenous communities.

Recommendation 2: Incorporate multistakeholder and rightsholder input into newborn screening priorities.4 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should establish a multistakeholder/rightsholder advisory body to provide input to the national leadership identified in Recommendation 1. This advisory body should identify high-level, cross-agency, cross-state, and cross-system challenges; elevate potential solutions to those challenges; inform the development of a strategic plan; and monitor and advise on progress in its implementation. The advisory body should engage wide-ranging expertise and experiences to inform the strategic plan and enable all partners to understand their role in driving it forward.

Currently, the discretionary HHS ACHDNC provides recommendations to the HHS secretary on newborn and childhood screening. The scope of ACHDNC’s mandate is theoretically broad, and has encompassed discussions around timeliness, long-term follow up, and

___________________

4 The term rightsholder is incorporated to recognize use of this term among Native American and Indigenous communities and to reflect their distinct legal and political contexts.

laboratory standards, among other issues. However, its attention and actions are primarily directed toward reviewing conditions for inclusion on the RUSP. This emphasis is responsive to the importance of evidence-based decision making but limits ACHDNC’s capacity to focus on overarching strategy, and its current membership does not comprise the full breadth of expertise and experiences that would be necessary for this more strategic advisory mission. As currently designed, ACHDNC and other existing avenues (e.g., state advisory boards, professional society working groups, symposia) are not suitable for this role, which requires broader expertise and connection to national leadership to provide authority, accountability, and resources to enact the vision informed by this advisory body.

The multistakeholder/rightsholder advisory body called for in Recommendation 2 could be established in different ways, including as a formal federal advisory committee realizing the full scope of ACHDNC’s mandate or through other federal or nongovernmental convening mechanisms. A wide range of expertise and perspectives will be needed, including

- state and territorial NBS program directors, laboratory experts, and follow-up experts;

- prenatal and birth care providers;

- health care professionals such as genetic counselors, pediatricians, and disease specialists;

- members reflecting family and rare disease community organizations and perspectives;

- representatives from the multiple federal agencies supporting public health newborn screening;

- philanthropic organizations active in this area; and

- the private sector.

Federal guidance on which conditions to include in state NBS panels—the RUSP—was established in 2010. Although not a mandate, the RUSP remains an important source of evidence-based guidance, and striving for RUSP alignment promotes consistency across NBS programs. However, the current process for incorporating new conditions onto the RUSP is long, taking an average of 3 to 4 years (not including additional time at the state NBS level); it is burdensome for advocacy organizations that often shoulder the weight of attracting the attention and funding that drive evidence generation to support consideration for the RUSP; and it is frustrating for all.

Recommendation 3: Optimize decision making on conditions included in newborn screening. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and state and territorial newborn

screening (NBS) programs should optimize the process of considering conditions in public health newborn screening:

- HHS leadership should designate a focused committee or mechanism to provide advice on the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), composed of appropriate experts and distinct from the strategic advisory body in Recommendation 2. In addition to advising on nominated conditions, this committee should (1) proactively assess which conditions could meet criteria for inclusion on the RUSP; (2) identify specific gaps in evidence necessary for RUSP decision making for conditions identified in this assessment and highlight what strategic research is needed (see Recommendation 8); and (3) periodically reassess evidence and consider whether RUSP removal is warranted for any condition based on knowledge gained from its implementation in public health newborn screening.

- HHS leadership should expand the scientific and technical capacity for reviewing evidence for conditions under consideration for addition to the RUSP, including exploring the applicability of rapid review mechanisms.

- State and territorial NBS programs should have a mechanism to consider implementation of RUSP conditions within a designated time line.

There are no simple answers for streamlining the RUSP evaluation process, and actions in Recommendation 3 represent a starting point. This recommendation could be achieved by focusing and enhancing the ACHDNC’s current mission. In the face of genomic sequencing technologies and ongoing therapeutic advances for rare diseases, groundwork needs to be laid for a future when an increased number of conditions that meet the inclusion criteria for newborn screening could be incorporated into the screening process. Exploring the implications of adopting or adapting alternative evidence-review processes may be a promising opportunity. Periodically reexamining the process for adding conditions to the RUSP would provide opportunities to revise it in light of an enhanced NBS system and future developments in platform screening technologies.

The scope of evidence evaluation for optimized RUSP decision making would need to include relevant scientific, clinical, and technical aspects of the condition; the disease’s effects and treatments; and implementation in public health screening. Issues related to NBS program operational feasibility are better addressed through supports to state-level

programs. As conditions are added to the RUSP, every state or territory needs a mechanism to consider these conditions in a timely manner, even if screening is not ultimately implemented. Successful implementation of high-quality screening across programs—and addressing operational barriers to including conditions on state and territorial NBS panels—will require more robust systems of support (see Recommendations 4 and 5).

Promote High Performance Among All NBS Programs

Variability is innate to any federated system, and state-run newborn screening is no different. States have the authority and knowledge to implement NBS programs to serve their constituents and comply with local requirements. Variability among programs can be beneficial as states are best situated to tailor their approach to the unique needs of their own population and jurisdiction, pilot different approaches and develop best practices, and act as resources among program peers. Other variability is detrimental, however, when it arises from insufficient resources or support and negatively affects health outcomes. All programs must achieve and maintain excellence in the core functions necessary to deliver on the promise of universal newborn screening.

Conclusion 4-1: While respecting the autonomy of each state and territorial NBS public health program to meet the needs of its population, all programs need to be accountable for achieving certain essential functions:

- Provide every infant born in the state or territory with the opportunity to receive screening for a set of serious, urgent, and treatable conditions.

- Provide NBS educational materials to all state/territorial prenatal and birth providers.

- Strive for high-quality, timely screening designed to perform accurately for all members of the population.

- Ensure high-quality and timely case management for every infant screened. This includes directly communicating out-of-range results for infants to their providers, and ultimately to the family/caregiver, as well as confirming those infants are connected to further evaluation or care by documenting diagnoses. This also includes reporting in-range results such that every infant’s results are communicated to their provider, and ultimately to the family/caregiver.

- Establish and maintain systems for quality assurance, program excellence, and performance improvement.

Strengthening the network of NBS programs so all 56 have what they need to achieve high performance requires more systematic data

collection and analysis and more strategic alignment of financial and nonfinancial supports and incentives for program participation and quality improvement.

Recommendation 4: Support newborn screening (NBS) program excellence in performance system. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leadership (Recommendation 1) and state/territorial NBS program directors should partner to establish a universal performance improvement system. Data collected should enable each program to assess its laboratory and followup performance, benchmark with peers, and iteratively improve its processes. To accomplish this the following need to occur:

- HHS should incentivize participation from all programs.

- HHS should collaborate with state and territorial NBS program directors to identify a common set of performance metrics all states will collect to monitor and improve laboratory and follow-up performance.

- State- and territorial-run NBS programs should agree to participate and commit to using collected data to close gaps and pursue excellence.

- HHS should provide responsive financial investment and technical assistance based on performance assessment.

A universal NBS performance system could build on existing efforts and entities that rely on voluntary submission from NBS programs, such as the Association of Public Health Laboratories’ (APHL’s) Newborn Screening Technical assistance and Evaluation Program (NewSTEPs) data repository and resource center, supported by a grant from HRSA. These efforts have limited or partial participation, and the data collected are not analyzed or used to inform responsive or strategic improvement and support. This recommendation calls for a more effective approach that will require incentives for broad program participation, alignment on a common set of metrics, and responsive funding and technical assistance based on identified performance improvement opportunities beyond existing ad hoc or grant-based federal resources.

NBS programs vary in their resources, expertise, and capacities for advanced technical analysis of newborn blood spots, development and implementation of new screening assays, establishing connections with specialized genetic counseling and clinical care resources for screened conditions, and other factors. Every NBS program does not need to directly house all such capacities, expertise, and resources, but it is essential for each program to have access to these resources when needed. Establishing cross-network infrastructure would aid programs and ensure that

resources, especially scarce ones, are used efficiently to strengthen all programs and benefit all infants born across the United States.

Recommendation 5: Amplify newborn screening (NBS) program excellence through shared resources. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leadership (Recommendation 1) should foster NBS programs’ ability to efficiently access and use specialized resources and expertise. To achieve this, HHS should survey NBS program directors to identify each program’s capacities, strengths, and sources of specialized expertise in both laboratory and follow-up performance; assess this resulting landscape; and establish infrastructure for more systematic and efficient use of shared resources among programs.

By analyzing the landscape of program capacities and developing a centralized repository of information, the unique strengths, specialized resources, and expertise of different NBS programs can be efficiently used throughout the system to facilitate connections between programs.

Fulfilling Recommendations 4 and 5 would require establishing an implementing mechanism with overall guidance and accountability provided by HHS leadership established in Recommendation 1. Additional strategies to implement this recommendation could include establishing or designating formal or informal centers for expertise providing technical assistance or direct services to partner programs in specific areas. This could include, for example, laboratory testing and implementation, expert clinical management guidance, clinical care handoff, or long-term follow-up. Partnership and resource-sharing agreements may need to be established to enable broad participation in a networked system. HHS would need to provide guidance and support, working in collaboration with NBS program directors.

Strengthen the Trustworthiness of NBS Programs

Limited public awareness about what newborn screening is and why it is undertaken, coupled with recent lawsuits over the storage and use of residual newborn dried blood spots, threaten to undermine trust in newborn screening. Transparency and engagement are needed so programs can continue to earn the trust of the public and provide newborn screening as an essential public health service. To build trust, longstanding calls for more systematic information for parents and caregivers about newborn screening during the perinatal period must be met.

Recommendation 6: Expand public and professional newborn screening (NBS) education and awareness. Engagement with

pregnant individuals, parents, and caregivers should occur at multiple points during the perinatal period. This education should start in the prenatal period and cover the purpose of newborn screening, when and how it will happen, what to expect after blood spot collection, parental options, and communication of the infant’s results.

- All professional associations involved in perinatal and infant care should issue recommendations for communicating about newborn screening with pregnant patients, parents, and/or caregivers and support accurate communication through professional education.

- The multistakeholder/rightsholder advisory body described in Recommendation 2 should work with relevant professional societies, patient/family organizations, and experts in effective public communication to design goals and communication approaches that can be adapted to local contexts, drawing on existing materials and research.

After NBS tests are completed, residual, or leftover, dried blood spots may remain. These residual dried blood spots are essential for program quality control and assurance efforts. Dried blood spots can also be useful for research. Few consistent policies at the federal, state, tribal,5 or laboratory level exist for retention and use of dried blood spots and derived data, and parental disclosure or consent policies also vary. The fact that some states have allowed law enforcement access to NBS dried blood spots for criminal or civil liability also raises legal and public trust concerns. This is a controversial area, subject to recent and ongoing litigation. Developing clear and transparent federal and state protections for dried blood spot and derived data retention, sharing, and use is necessary to act in trustworthy ways and avoid federal constitutional challenge.

Recommendation 7: Specify standards for the retention, sharing, and use of newborn dried blood spots and derived data.

-

State legislatures should set law and policy for the retention, sharing, and use of newborn dried blood spots and any derived data. These policies and laws should do the following:

- Protect the retention of newborn screening (NBS) dried blood spots for at least a limited period for primary

___________________

5 Additional clarifications may be needed to understand legal authorities over newborn dried blood spots collected in tribal health care settings, jurisdiction of tribal data sovereignty, and applicable state laws governing NBS programs.

-

- public health screening goals including, but not limited to, retesting samples, quality assessment, and quality improvement.

- Set transparent practices for the retention, sharing, and use of dried blood spots for purposes other than those described above, including research.

- Allow parents the option to request the destruction of their child’s specimen after the limited time period of retention for primary public health screening goals, and allow the dried blood spot contributor the option to request the destruction of their own specimen when they reach the age of 18.

- Prohibit the sharing or use of NBS dried blood spots and derived data to conduct criminal, civil, or administrative investigations and/or impose criminal, civil, or administrative liability on the NBS contributor or blood relatives.

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leadership (Recommendation 1) should provide national guidance or recommendations on these standards.

- HHS leadership and state legislatures should establish additional guidance if NBS programs begin implementing genomic sequencing methods that increase the generation and identifiability of sensitive data.

Preparing Newborn Screening for the Future

Evidence is needed to guide decision making about NBS policies and practice. However, research providing such evidence is often funded and completed too late to inform programmatic and policy decision making, not responsive to the most pressing needs of the system, or comprised of multiple small studies limiting the ability to draw clear conclusions and hindering the impact of NBS research investments. Indexing newborn screening in the NIH Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization system would also improve assessment of the federal government’s investment in NBS research, particularly for investigator-initiated funding.

A national plan with associated research infrastructure would help ensure that research informing newborn screening is more strategic, coordinated, nimble, and has allocated sufficient resources to provide the evidence needed for newborn screening to adapt to a rapidly changing landscape.

Recommendation 8: Expand and coordinate research to inform newborn screening (NBS) policy and practice. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should establish an NBS research network with centers that address system-level

research priorities in a coordinated and nimble manner. This network of research centers should operate in partnership with state/territorial NBS public health programs as appropriate to carry out research in the following areas:

- Defining diseases to guide screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

- Developing laboratory tests and applying emerging technologies.

- Understanding ethical, legal, and social issues.

- Investigating public health practice, feasibility, and impact.

Involving patient advocacy groups in an NBS research network would facilitate bidirectional communication to inform responsive research. Centers in the network would work together to generate evidence to address high-priority issues, improve the process of conducting NBS research, and inform analyses around delivery, quality, cost, and outcomes. Investing more systematically and strategically in NBS research would also help advance rare disease research by informing the development of treatments and other related priorities. This recommendation is not meant to replace all federally funded investigator-initiated NBS research, which remains important in promoting creativity and elevating questions identified by investigators throughout the community. In addition, the network resources need to be accessible to outside investigators.

The application of new technologies to newborn screening has garnered significant attention and investment. The use of emerging technologies by NBS programs must be considered through the lens of achieving, rather than changing, the goals of universal, public health newborn screening. Therefore, decisions on the inclusion and role of emerging technologies require the same level of scrutiny, analysis, and alignment with public health values and principles as any other decision affecting the practice of public health newborn screening.

One of the technologies currently attracting the greatest interest, research attention, and momentum is DNA sequencing, which is already used in limited ways in some NBS programs. New approaches for genomic sequencing could facilitate screening for all genetic conditions that meet the inclusion criteria for newborn screening using a single platform as a first step.6 Such approaches could generate a tremendous amount of data—much of which would not be relevant to newborn screening as

___________________

6 DNA sequencing across the entire genome is often referred to as whole genome sequencing (WGS). This term can be misinterpreted as it suggests that the genome is fully sequenced, analyzed, and reported in its entirety. WGS may generate data across the genome, but not all the sequencing data are typically analyzed and interpreted into reportable results. This report uses the term genomic sequencing to avoid this confusion.

a public health initiative. The use of genomic sequencing for panels of conditions that align with the goals of public health newborn screening has promise, but technical, ethical, psychosocial, and implementation questions would need to be addressed before this technology could be implemented as a primary NBS approach outside of consented study contexts. Key questions can guide the investments and activities of funders and investigators across government, academia, nonprofit organizations, and industry.

Recommendation 9: Promote the responsible application of technologies to newborn screening (NBS). Funders and investigators of feasibility studies should address the following key scientific, technical, ethical, and implementation questions before considering genomic sequencing for public health newborn screening:

- What sequence should be generated, what sequence/variants should be analyzed and interpreted, and what results should be returned?

- What strategies are necessary to ensure the accuracy of variant interpretation across ancestral populations?

- What are public attitudes concerning the application of genomic sequencing into public health newborn screening as a first-tier screening tool?

- What data should be stored after screening, if any, and how will the privacy of genomic data be protected given its risk of reidentification?

- Is genomic sequencing as a first-tier screening methodology cost-effective?

- What funding, resource sharing, and/or distributed system of clinical expertise would be necessary and effective to support employing population-based genomic sequencing as a first-tier tool across NBS programs?

FINAL THOUGHTS

The future of public health newborn screening needs to remain rooted in its fundamental purpose to screen all infants for conditions that are serious, urgent, and treatable, and connect those at risk with diagnosis and care. Delivering on this promise across all states and for all infants will require greater national coordination to align the many partners that support newborn screening and drive forward the recommendations proposed in this report. Table S-1 provides a high-level summary of opportunities for actors throughout the NBS ecosystem to help translate these recommendations into practice.

TABLE S-1 An Action Agenda for the NBS Ecosystem

| Actor | Select Action |

|---|---|

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) |

|

| Federal agency partners |

|

| NBS programs |

|

| State legislatures |

|

| Patient and family organizations |

|

| Actor | Select Action |

|---|---|

| Health providers and care settings |

|

| Professional associations and societies |

|

| Researchers in areas relevant to newborn screening |

|

NOTE: NBS = newborn screening; RUSP = Recommended Uniform Screening Panel.

This page intentionally left blank.