Early Relational Health: Building Foundations for Child, Family, and Community Well-Being (2025)

Chapter: 3 Influences on Early Relational Health

3

Influences on Early Relational Health

Chapter Highlights

- Early relational health emerges from various factors spanning multiple domains of influence.

- Individuals, familial and extrafamilial relationships, community organizations and systems, public policy, and social and environmental characteristics influence early relational health.

- Early relational health offers a pathway toward scalable preventive solutions at the individual, community, and society levels.

Early relational health emerges from numerous factors spanning multiple domains of influence. For centuries, scholars have suggested that a full understanding of human life requires understanding how individual lives occur in specific times and places (Barker & Wright, 1949; Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Dewey, 1930; Lewin, 2004; Vygotsky et al., 1978). This chapter provides an overview of many domains, including (a) individual, (b) relational, (c) resource (including social drivers of health), (d) community, and (e) macro factors. Understanding these factors can inform interventions to enhance early relational health and ultimately advance children’s flourishing and long-term outcomes. (See also Chapters 4 and 5.)

Along with delving into them separately, it is important to consider how the factors fit together holistically in the lives of children, families,

and communities. These influences do not exist independently of each other, but rather may be viewed as constellations, recognizing the inherent interrelations among features of an individual’s life (Rogoff et al., 2014). Thus, any single characteristic does not determine early relational health, and the different aspects are interrelated. The framework of how multiple factors influence early relational health as described in this chapter is informed by several perspectives:

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC; 2022) social-ecological model, which includes individual, relational, community, and societal factors.

- Closely aligned with the CDC framework is Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007), which includes micro-, meso-, exo-, and macro-system influences on child development (see O’Dean et al., 2025, for an application of this framework to early relational health).

- The ecobiodevelopmental model (Garner et al., 2012; Shonkoff et al., 2012), which explains how the dynamic interplay between a child’s genetic predisposition and their social and physical environments has enduring effects on health and well-being over time.

- The Life Course Health Development framework (Halfon & Hochstein, 2002), which conceptualizes health as an emergent, dynamic, and developmental process that unfolds over time, with early adversities becoming biologically embedded and exerting lasting effects on adult health. Notably, this framework underscores the importance of examining timing, developmental trajectories, and life transitions to identify critical periods for intervention that may alter long-term patterns of health and well-being (Halfon et al., 2022).

- The Indigenist Ecological Systems Model (Fish et al., 2022), which adds multidirectional arrows to the prototypical socioecological diagram and emphasis on the importance of the chronosystem (time) to convey the reciprocal relations among the layers in the circles, based in Indigenous knowledge systems.

- Wesner et al. (2025) presented a conceptual model of Indigenous early relational well-being that seeks to reflect the multitude of relationships and practices that are the “seeds of connectedness” in early childhood.

As the most proximal factor during early development, caregiving and home environments—typically provided by parents, extended family members, and childcare providers—play a central role in supporting early relational health (Britto et al., 2017; World Health Organization et al., 2018).

However, the capacity to foster early relational health is not determined by parenting and proximal factors alone. It is also shaped by the social ecology surrounding the family. Social drivers of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, and include factors such as access to nutritious food, stable housing, quality childcare, transportation, social support, and cultural values and practices. These drivers also encompass factors such as racism, economic inequality, gender norms, ableism, sexual stigma, immigration status, and neighborhood infrastructure (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2006). Collectively, these broader factors can either support or impede early relational health.

A social-ecological perspective broadens the lens beyond the individual or dyadic level to consider the interconnections between individuals, families, communities, institutions, and systems (Willis et al., 2024). To expand the scope of the research on adverse childhood experiences (see Chapter 2), Ellis and Dietz (2017) described the relationship between adversity within a family and adversity experienced within a community as a “pair of ACEs”—adverse childhood experiences and adverse community environments. They asserted that adverse community environments and social inequities—such as persistent poverty, violence, and racism—can also negatively impact child development (Ellis & Dietz, 2017). Such perspectives allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how the social and structural context interacts with everyday caregiving. Within this framework, a holistic approach is essential, one that considers cultural norms, community resources, institutional practices, and public policies, and how these interact to shape health and developmental outcomes. As Charlot-Swilley et al. (2024) noted, holistic perspectives “consider all dimensions of human experience and context” to support health, wellness, and flourishing across diverse populations (p. 561).

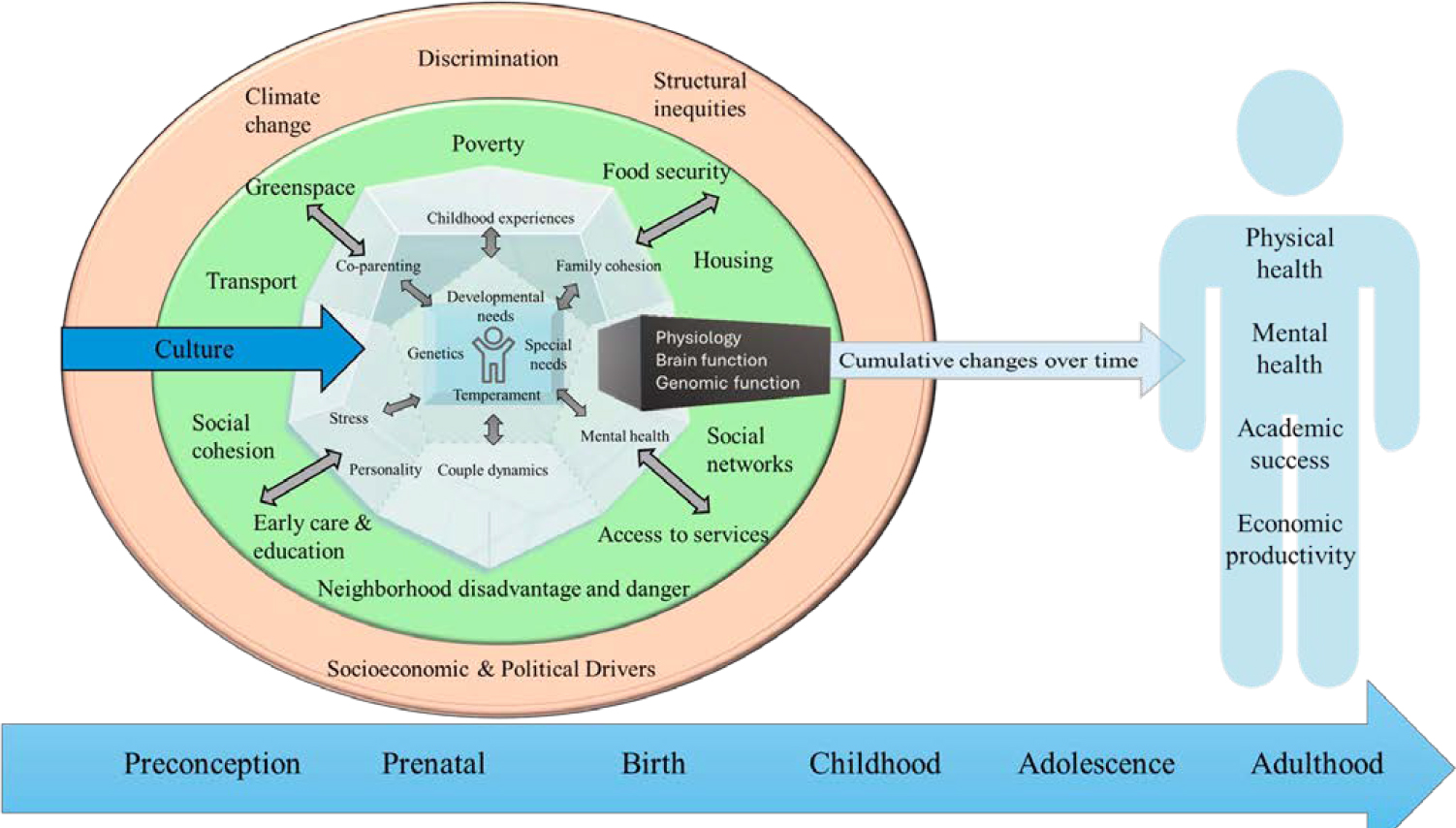

An adapted version of the conceptual model and environmental context from Vibrant and Healthy Kids (see Figure 3-1; NASEM, 2019c) aligns with the early relational health framework, illustrating how parental well-being and relational capacity are shaped by concentric layers of influence, ranging from individual and family factors (e.g., social connections, family cohesion) to broader determinants such as healthy living conditions, early care and education, and health systems. Structural inequities, socioeconomic conditions, and political drivers sit at the outermost layer, emphasizing the distal yet powerful forces shaping parent–child relationships.

Taken together, the abovementioned frameworks highlight that early relational health emerges from the interplay of biology, caregiving, and broader social ecologies. The CDC’s model and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory situate families within nested systems, while the Indigenist Ecological Systems Model emphasizes reciprocity, cultural knowledge, and the importance of time. The ecobiodevelopmental and Life Course Health

SOURCE: Committee generated. Adapted from NASEM, 2019c.

Development frameworks highlight how early experiences become biologically embedded and shape long-term trajectories. Collectively, they align with the model outlined in Figure 3-1 by showing how proximal caregiving is continuously shaped by community resources, cultural contexts, and structural conditions, reinforcing the need for holistic approaches to support early relational health.

These multiple perspectives have contributed to the committee’s view of the complex and interrelated aspects of the ecologies of early relational health. Rogoff’s (2014) idea of the ecological constellations of children’s lives further illuminates the complex interrelations among the multiple aspects of children’s ecologies. Rogoff (1995, 2003) proposed looking at the multifaceted ecological context by means of lenses focused on different aspects of the whole constellation. This lens metaphor represents the mutually constituting and dynamic nature of multiple aspects of the ecological constellation, without separating them into layers or levels. Each lens focuses on one aspect of the whole process but keeps other aspects in the background in less detail, not separate from the aspect that is in focus (Rogoff, 1995, 2003; see Figure 3-2).

Although the lenses in Figure 3-2 focus on three aspects of the constellation—individual, relational, and community/institutional aspects—additional lenses can provide focus on additional perspectives (e.g., focusing

NOTE: Rogoff (1995, 2003) proposed that the focus of different viewers (or disciplines) through different lenses could focus on individual processes, interpersonal processes, community/institutional processes, or other processes of children’s lives. The focus of a specific lens provides details on that aspect of the overall, mutually constituting process and at the same time provides less-detailed recognition of other aspects in the background.

SOURCE: Adapted from Rogoff, 2003.

on neuronal, hormonal, epigenetic, societal, legal, and economic facets; Rogoff, 2024). Multiple lenses thus improve understanding of the multidimensional complexity of aspects that together dynamically compose human development (Rogoff, 2024). The committee embraced this lens approach when considering an ecological perspective and the complexity of early relational health.

The sections that follow delve into the multiple influences on early relational health, considering the many aspects that contribute interdependently and dynamically to the process. It is important to recognize at the outset, however, that most of the studies described do not fully capture this complexity because of their focus on single variables and use of correlational study designs. In addition, most of the literature to date has primarily focused on attachment1 and parent characteristics, reflecting findings primarily from studies of middle-class European-heritage families. Additional research is needed on the variations that are reflected in the cultural values and practices of other communities, such as cultural differences in what forms of attachment are valued, what counts as sensitivity, and adults’ ethnotheories about their children’s development (Keller, 2007; Morelli et al., 2018; Super & Harkness, 1986). It will also be important to broaden the lens to include not only parents but other relatives (e.g., grandparents, older siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles [Weisner, 2014; Whiting, 1963]) and nonfamily caregivers (e.g., early care and education providers).

INDIVIDUAL FACTORS

Characteristics of the individuals within the relationship (i.e., the parent/caregiver and the child) influence early relational health. A parent’s history affects their parenting style and early relational health, and a parent’s attachment style predicts their child’s attachment style (see Verhage et al., 2016, for meta-analysis), consistent with the idea of intergenerational transmission of attachment. Conversely, in systematic reviews, parents’ adverse childhood experiences have shown to be associated with lower-quality parent–child interactions (Leite Ongilio et al., 2023; Weistra et al., 2025). Parents’ personality characteristics, including warmth, behavioral control, and autonomy support, are also associated with parenting behaviors that contribute to early relational health, with lower levels of neuroticism and higher levels of openness, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness predicting more positive parenting behaviors (see Prinzie et al., 2009, for meta-analysis). It is also important to acknowledge the millions of

___________________

1 Chapter 1 described differences between infant attachment and early relational health. Although there are differences, the overlap between these concepts means that many of the research findings on attachment help to further understanding of early relational health.

parents who have a disability or special health care need (Rivera Drew, 2009). Most research in this area has focused on parents with intellectual disabilities (as opposed to developmental, sensory, and physical disabilities; Schuengel et al., 2017). One review by Llewellyn and Hindmarsh (2015) highlighted “the need to address parental social skills, relationships and networks to reduce social isolation and increase social support” (p. 124) when working with parents with intellectual disabilities. There are very few studies of early relational health among parents who have disabilities.

Parents’ current functioning is another critical factor that impacts early relational health. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General (2024) recently called for greater attention to parents’ mental health and highlighted the need to reduce their stress and promote their well-being. A parent’s mental well-being and health difficulties affect early relational health in oppositive directions, with well-documented linkages between several aspects of parents’ mental health and indicators of early relational health. For example, parents who have better emotion regulation skills demonstrate more positive parenting behaviors and fewer negative parenting behaviors (see Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2022, for meta-analysis). Conversely, a large body of research examines linkages between maternal depression, parenting, parent–child relationships, and children’s functioning (see Goodman, 2020, for review), with meta-analytic work showing significant associations between higher maternal depressive symptoms and insecure infant attachment (Barnes & Theule, 2019). There is also meta-analytic evidence that paternal depression is associated with less positive and more negative parenting behaviors (Cheung & Theule, 2019). Additionally, there are linkages between parents’ post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, parenting, the parent–child relationship, and children’s functioning (for reviews, see Chasson et al., 2025; Meijer et al., 2023; van Ee et al., 2016), and between maternal substance use and less secure attachments in young children (see Hyysalo et al., 2022, for meta-analysis). Maternal depression, anxiety, and stress during the first year postpartum are also all associated with postpartum mother–infant bonding problems (see O’Dea et al., 2023, for meta-analysis).

Parents’ caregiving behaviors are both an important component of and contributor to early relational health. Sensitive, responsive caregiving predicts early relational health, with meta-analyses showing that maternal and paternal sensitivity are associated with infant and child attachment security (De Wolff & van Ijzendoorn, 1997; Madigan et al., 2024). Similarly, parents’ mentalization—the degree to which parents consider their infant’s internal states—is associated with infant attachment security, such that higher levels of parent mentalization are associated with more secure infant attachments (see Zeegers et al., 2017, for meta-analysis). These patterns may extend as early as the prenatal period; one meta-analysis showed

that parents’ thoughts and feelings about their child during pregnancy predicted observed parent–infant interaction quality (Foley & Hughes, 2018). Conversely, a parent’s increased technology use in their child’s presence has been associated with less secure attachments among young children age birth to 4.9 years (see Toledo-Vargas et al., 2025, for meta-analysis).

There has been much less research on how characteristics of other caregivers are associated with early relational health. This is a significant gap given that many young children spend at least some time each week with a nonparental caregiver (i.e., in relative care, nonrelative care, or center-based care), with data from the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (2021) indicating that 42% of children under age 1 year have at least one weekly nonparental care arrangement, 55% of children ages 1–2 years have at least one weekly nonparental care arrangement, and 74% of children ages 3–5 years have at least one weekly nonparental arrangement. The work that does exist reveals some similarities to the patterns described above. For example, Hamre and Pianta (2004) found that early childcare providers’ depressive symptoms were associated with less sensitive caregiving, more withdrawn caregiving, and more intrusive/negative caregiving. Similarly, Buettner et al. (2016) showed that early childcare teachers’ psychological load (depression, stress, and emotional exhaustion) was associated with more punitive and minimizing reactions to children’s negative emotions, whereas their healthy coping strategies (reappraisal, active coping, planning, use of instrumental support) were associated with more expressive encouragement and positive reactions to children’s negative emotions. In other work, early childcare workers’ emotion regulation abilities, responsiveness, and comfort with socioemotional teaching were all positively associated with caregiver–child relational closeness (Garner et al., 2019). Further consideration of how other characteristics of nonparental caregivers are associated with early relational health is an important task for future research.

Finally, young children’s negative emotionality has been shown in meta-analyses to be negatively associated with the number of secure attachment relationships they develop (Dagan et al., 2024). There is also some evidence that infant temperament is related to infants’ relationships with their parents (Kochanska et al., 2004) and parent–child interactions (Wilson & Durbin, 2012).

Other child characteristics are important to consider as well. For example, for children with developmental disabilities or special health care needs, their families may face unique challenges such as finding needed information and services, managing increased health care costs and other financial barriers, and feeling included in schools and communities (Resch et al., 2010); these challenges can increase parenting stress and affect early relational health (see discussions by Alexander et al., 2024; Frosch et al.,

2021). Furthermore, parent–child interactions may be altered for children with developmental delays. Baker et al. (2003) find the presence of developmental risk stresses the parent–child relationship and exploring ongoing interactions may offer a specific view of goodness of fit processes (see also Floyd et al., 2004). Likewise, premature birth may pose challenges for children’s social-emotional development (e.g., Cheong et al., 2017; Ritchie, 2015) and for the parent–child relationship (e.g., Forcada-Guex et al., 2011; Ionio et al., 2017; Korja et al., 2012; Singer et al., 2003).

In considering these and other characteristics, it is important to remember that the ecobiodevelopmental model (Garner et al., 2012; Shonkoff et al., 2012), described in the previous chapter and above, explains how the dynamic interplay between a child’s genetic predisposition and their social and physical environments has enduring effects on health and well-being over time. Accordingly, individual characteristics interact with characteristics of the broader environment to predict functioning. For example, theories of differential susceptibility (Belsky & Pluess, 2009) and biological sensitivity to context (Boyce & Ellis, 2005) suggest that highly reactive children may show particularly positive outcomes in the context of supportive environments or particularly negative outcomes in the context of challenging environments. Thus, the committee again emphasizes that individual characteristics are only one part of a complex constellation of influences on early relational health and other developmental outcomes, none of which should be considered deterministic. We also caution that many of these associations are likely to be bidirectional, such that individual characteristics shape and are shaped by early relational health, further underscoring its dynamic nature over time.

RELATIONAL FACTORS

Relational factors, another lens through which to see and understand human development, are also critical influences on early relational health. Family systems theory argues that families consist of a set of subsystems, each influencing and influenced by the others (P. Minuchin, 1985; S. Minuchin, 1974). As one such subsystem, the parent–child relationship—including that early in development—is thus likely to be affected by other subsystems within the family. Indeed, there is evidence of associations between early relational health and both the couple relationship and the coparenting relationship. Regarding links between the couple relationship and early relational health, there is long-standing meta-analytic evidence that couple relationship quality is positively associated with parent–child relationship quality throughout development (Erel & Burman, 1995), reflecting a pattern of “spillover,” in which the qualities of one relationship (the parents’ romantic relationship) spill over to affect another relationship

(the parent–child relationship). Conversely, interparental conflict is negatively associated with early relational health. One meta-analysis found that interparental conflict (i.e., overt and covert conflict between partners) was negatively associated with children’s attachment security in early childhood (age 5 years and under; Tan et al., 2018). Intimate partner violence has also been shown to be associated with less secure child attachment, with these associations particularly strong in infancy (see Noonan & Pilkington, 2020, for meta-analysis). Other meta-analytic work shows that maternal exposure to intimate partner violence was negatively associated with their young child’s (ages 1–5 years) attachment security measured at least 6 months following exposure to violence (McIntosh et al., 2019). These patterns are consistent with emotional security theory (Davies & Cummings, 1994; Davies & Woitach, 2008), which argues that family conflict undermines children’s sense of security and safety.

The quality of the coparenting relationship also predicts early relational health. Coparenting refers to the “ways that parents and/or parental figures relate to each other in the role of parent” (Feinberg, 2003, p. 96). It is related to but distinct from couple relationship quality (see Ronaghan et al., 2024) and can be used to characterize relational dynamics between parents who are romantically involved as well as those who are not romantically involved. Qualities of the coparenting relationship have been shown to be associated with the parent–child relationship. Meta-analyses show that several dimensions of coparenting quality are associated with children’s attachment to their parents (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010), such that higher levels of cooperation, lower levels of conflict, and lower levels of triangulation2 are associated with more positive attachment with parents. Regarding links to early relational health specifically, several studies have shown significant concurrent and/or longitudinal associations between higher coparenting quality and more secure child attachments during infancy and toddlerhood (Brown et al., 2010; Caldera & Lindsey, 2006; C. Y. Kim et al., 2021; Pudasainee-Kapri & Razza, 2015), and with more positive parent–child relationship quality during toddlerhood (Holland & McElwain, 2013).

Other relationships may affect early relational health as well. Within the family, the presence (or absence) of siblings has been shown to affect attachment security during early childhood (Teti et al., 1996), and grandparents are also likely to have an important influence on early relational health (see discussions by Drew et al., 1998; Frosch et al., 2021). More broadly, relationships outside the family are also likely to contribute to early relational health (see Belsky & Fearon, 2008, for discussion). For example, more social support has been associated with more frequent mother–child interactions during infancy and toddlerhood (Green et al.,

___________________

2 Triangulation is a process in which a child is drawn into conflict between two parents.

2007), and parents’ use of social support has been associated with more secure attachment among preschoolers (Coyl et al., 2010). More research is needed to understand the multiple individuals who matter in young children’s relationships and what sort of relationships are valued across a range of communities.

RESOURCE FACTORS

Resource factors and the social drivers of health can be grouped into five key domains: economic stability, education access and quality, health access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). The importance of these domains on parenting (NASEM, 2016) and child health (NASEM, 2019a,c, 2024a) is well established. There is significant evidence that social drivers of health can disrupt early relational health. For example, conditions such as poverty, unemployment, housing instability, and food insecurity place chronic stress on families, contributing to emotional distress in caregivers, including heightened levels of anxiety and depression (Gard et al., 2020; Hunter & Flores, 2021; Judd et al., 2023; McLoyd, 1990; Newland et al., 2013). These stressors are also associated with increased conflict within the home (Justice et al., 2025; Kavanaugh et al., 2018), which can compromise parents’ capacity to provide sensitive, responsive, and nurturing care—all fundamental processes to early relational health. Over time, these stressors can weaken the quality of early relationships and interfere with children’s development. By examining how societal circumstances influence parenting, we can better understand how broader social and economic conditions become embedded in everyday interactions, with lasting impacts on child health development (Rose et al., 2024). This socioecological perspective, aligned with the ecobiodevelopmental model, recognizes how communities, policies, and systems influence caregiver well-being and relational capacity across the life course. These multilevel influences shape the biological and social-behavioral pathways that support early relationships, which in turn lay the foundation for lifelong health and development.

Economic Security

Children remain the poorest age group in America, with poverty disproportionately impacting Black, Indigenous, and other children of color; those in single-mother households; and those living in rural areas and the South, reflecting the ongoing and long-standing system-level drivers of unequal access to opportunity and resources (NASEM, 2019b, 2024b). Even brief periods of poverty can have lasting negative effects on

children’s development and long-term outcomes, including worse physical outcomes (Schickedanz et al., 2015) and detriments to school readiness and educational achievement (Blair & Raver, 2015; Duncan et al., 2010). The landmark National Academies report A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty confirmed that income poverty itself directly undermines children’s health, development, and future success, particularly when it occurs early in life or persists throughout childhood (NASEM, 2019b; see also Duncan, 2021). Nearly 14% of children in the United States live in poverty (Jenco, 2024), with the highest rates among children under age 5 years, where one in six (or 3 million children) are poor. Almost half of all children in poverty live in severe or extreme poverty, a number that rose from 4.5 million to 5.5 million following the COVID-19 pandemic (Children’s Defense Fund, n.d.).

While poverty is a direct predictor of child health, it can also function indirectly through its effects on family relationships (Magnuson & Duncan, 2019). The Family Stress Model (Conger et al., 1992) proposes high financial strain negatively impacts parental mental health and interparental conflict and behavior, which, in turn, negatively impact child well-being. Several potential mechanisms linking family income to child outcomes have been proposed: parental stress (McLoyd & Wilson, 1994; Mistry et al., 2002, 2004); parental self-esteem (Brody & Flor, 1998); parental mental health, in particular, depression (Brody et al., 1994; Fitzsimons et al., 2017; McLoyd, 1990; Wilson et al., 2025); authoritarian or harsh parenting practices (McLeod & Shanahan, 1993; Mistry et al., 2002, 2004); and positive parenting (Gershoff et al., 2007).

When families face economic constraints due to system-level factors, relational health (e.g., in parent–child relationships) can also buffer or exacerbate the effects of low socioeconomic status, thus acting as a protective factor. For example, parental warmth and support can moderate the negative effects of financial hardship on child mental health (Kirby et al., 2022), providing a buffering response to children’s physiological stress reactivity profiles (Brown et al., 2020), brain volume (Brody et al., 2017), and neural connectivity (Brody et al., 2019).

At the extreme end of the early relational health continuum is child abuse and neglect, which reflects a serious breakdown in the nurturing relationships essential for healthy development. Poverty can increase the risk of child maltreatment by placing significant stress on caregivers and limiting the resources needed to support safe, responsive caregiving. Families living in poverty are disproportionately involved with the child welfare system, with studies showing that many families investigated for neglect have incomes below the federal poverty level and often face structural barriers such as unstable housing, food insecurity, and limited access to services (Kim et al., 2024; Okechukwu & Abraham, 2022; Skinner et al., 2025). Family poverty, income volatility, and parental stress and depression

are associated with increased risk of child maltreatment (Berger & Waldfogel, 2011; Berger et al., 2015; Monahan, 2020; Paxson & Waldfogel, 2002; Sedlak et al., 2010; Slack et al., 2003). When caregivers are under financial strain, they may be unable to adequately meet children’s basic material, safety, and medical needs, which increases risk of neglect (Yang, 2015). Chronic economic strain also increases risk of child maltreatment by increasing parental stress and depression, which can contribute to harsh parenting behaviors (Berger, 2007; Berger & Waldfogel, 2011; Schneider & Schenck-Fontaine, 2022).

Food Security

Food insecurity is defined as limited or uncertain access to nutritionally adequate and safe foods (Rabbit et al., 2024). A recent U.S. Department of Agriculture report indicated that in 2023, food insecurity continued to affect approximately 13.5% of U.S. households (Rabbit et al., 2024). Among households with children, 8.9% experienced food insecurity at some point during the year, with 1.0% experiencing very low food security—a severe form of food insecurity, indicating disrupted eating due to lack of resources. Roughly 58% of food-insecure households accessed one or more major federal nutrition programs (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; or the National School Lunch Program) in the month before the survey (Rabbit et al., 2024).

Food insecurity is both a nutritional risk and a stressor for parents and children dealing with food shortages. During pregnancy, food insecurity is associated with increased risk of maternal stress and mood disorders (Bell et al., 2024); however, these effects were attenuated in women who received food assistance (Chehab et al., 2025). Overall, children living in food-insecure households have worse mental health outcomes (Cain et al., 2022; Drennen et al., 2019) and more problems with linguistic development, school performance, and social interactions (Alaimo et al., 2001; de Oliveira et al., 2020).

The Family Stress Model has been extended beyond economic hardship, with an adapted model suggesting that food insecurity adversely affects child outcomes through compromised parenting associated with increased parental stress and mental health problems (Ashiabi & O’Neal, 2008). Emerging evidence supports the notion that food insecurity impacts parental function and parenting. As noted above, food insecurity is associated with increased parental stress and mood disorders (Belans et al., 2024; Bell et al., 2024; Cain et al., 2022; Liebe et al., 2024). One recent study, following women during the perinatal period, found that women with very low food security reported significantly higher levels of stress and lower levels

of mother–infant bonding during the first year postpartum, compared with participants with higher food security (Shreffler et al., 2024). Other studies have shown that caregiver stress and mental health, as well as disrupted parenting practices (e.g., lower warmth and responsiveness), partially mediate the association between food insecurity and cognitive development in toddlers (Bronte-Tinkew et al., 2007) and behavioral problems in school-aged children (Slack & Yoo, 2005). Particularly relevant to early relational health, a large longitudinal cohort study (Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort; N = 6,400) with parents of children under age 5 years found that both early and concurrent food insecurity were associated with an increased likelihood of using harsh discipline and a decreased probability of having rules about foods and less frequent meal routines (e.g., eating together as a family and at regular times), suggesting difficulties in supporting young children’s daily routines and in creating a stable and nurturing environment around meals and general caregiving (Nguyen et al., 2020).

Housing Security

The home represents more than a physical dwelling; it is a dynamic and multifaceted context that plays a foundational role in parenting and the socialization of children (Dunn, 2020). As the primary setting in which caregiving takes place, the home encompasses relational, emotional, and material dimensions that shape children’s early experiences and development. From a psychological perspective, it is closely related to the concept of identity as it is an expression of the self and of one’s values and culture; the home is also an indicator of status (Bartlett, 1997). In addition, a home is typically regarded as a sanctuary—a place where one can have a sense of security and control and take refuge from the world (Easthope, 2004). It serves as the earliest context for relational learning, where children begin to learn about relationships, norms, routines, and expectations through daily interactions with caregivers and the environment.

Housing insecurity encompasses multiple dimensions of housing-related challenges, including problems with affordability, safety, housing quality, and residential stability, as well as the risk of eviction or homelessness (Hanson, 2025; Swope & Hernández, 2019). It is a fundamental social determinant of health, with parents and children especially vulnerable to its instability and associated health consequences (Hanson, 2025; Hatem et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2008; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.; Ramphal et al., 2023; Ziol-Guest & McKenna, 2014). In 2021, 39% of U.S. households with children had one or more of three indicators of housing instability (physically inadequate housing, crowded housing, or housing cost burden greater than 30% of household income; Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family

Statistics, 2023). Six in ten people experiencing homelessness are under age 18 years, and more than 58,000 families, including over 100,000 children, experience homelessness on any given night (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, n.d.). These figures are likely an underestimate of the prevalence of homelessness, given that the numbers represent only those accessing homelessness services. In addition, housing stability in the United States is increasingly threatened by rising rates of eviction, foreclosure, gentrification, and climate-related disasters (Swope & Hernández, 2019), many of which lie outside the control of individual households. These challenges are unfolding within a deepening and multifaceted housing crisis, marked by historically high housing costs. Notably, patterns of housing insecurity and eviction reveal significant disparities, disproportionately affecting racially/ethnically minoritized groups, economically marginalized (especially single-parent) households, and families with children (Gan & McCarthy, 2025; Graetz et al., 2023; NASEM, 2016).

Housing instability has a significant impact on children and families (Allen & Vottero, 2020; DiTosto et al., 2021). It has been linked to reduced parental self-efficacy and a more negative view of oneself as a parent (Bradley et al., 2018); higher levels of mental health problems, including depression and anxiety (Ludlow et al., 2025; Sandel et al., 2018); parenting stress (Lebrun-Harris et al., 2024); increased risk of intimate partner violence (Pavao et al., 2007); and harsher parenting behaviors (Marçal, 2021; Marçal et al., 2023), including a heightened risk of child maltreatment (Chandler et al., 2022). Recent evidence shows that neighborhood-level threats of eviction can also adversely affect maternal and infant health, including increasing the risk of preterm birth among Black women (Sealy-Jefferson et al., 2025). These challenges may negatively affect health outcomes in children across development (Bess et al., 2023; Cutts et al., 2011; Hanson, 2025; Hock et al., 2023; Keen et al., 2024; Sandel et al., 2018).

Frequent moves or forced displacement can also disrupt children’s continuity of care and their attachment relationships with early education and childcare providers, neighbors, and other trusted adults in their community (DeCandia et al., 2022; Ziol-Guest & McKenna, 2014). Because many infants and toddlers spend significant time with caregivers outside the home, disruptions to these other place-bound relationships can undermine children’s socioemotional development, health, and learning (Cutts et al., 2011; Reece, 2021). Housing instability can also interrupt access to food security programs and continuity of pediatric care, further compounding stressors for parents and children (Carroll et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2021). These disruptions make it more challenging for families to maintain consistent, supportive relationships that are important to early relational health.

Whiting (1980) and Bartlett (1997) emphasize that caregiving is not solely a matter of proximal interactions between parent/caregiver and child

but also an expression of how parents/caregivers respond to and structure the child’s environment. This includes the physical organization of household space, the establishment of routines, and the provision of opportunities for play and learning. A key dimension of the physical environment that can affect these aspects of caregiving is household crowding, which has implications for both parenting and child development. High levels of residential density have been linked to increased caregiver stress, reduced opportunities for privacy or quiet, and fewer structured routines, all of which can affect parenting behaviors and family dynamics (Evans, 2006; Kent et al., 2024). For children, crowded conditions can limit opportunities for play, learning, and rest, and are associated with elevated behavioral and emotional difficulties (Reynolds-Salmon et al., 2024; Solari & Mare, 2012). These effects often intersect with socioeconomic disadvantage, compounding their impact.

A social-cultural lens further highlights that the structure and experience of homes and communities are shaped by cultural practices, social norms, and broader structural conditions (Rogoff, 2003; Super & Harkness, 2002; Weisner, 2002; Whiting, 1963). The organization of space, household roles, and the interpretation of children’s needs reflect deeply embedded cultural models of parenting and development. For instance, multigenerational living or shared sleeping arrangements, which may be interpreted in middle-class contexts as crowding, may be normative and valued in other cultural contexts, offering emotional support and intergenerational caregiving (Morelli et al., 1992). This perspective invites a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes a stable or supportive home, emphasizing that early relational health is influenced not only by housing security but also by the culturally embedded ways families and communities organize and experience home and community life.

One of the most important cultural differences in early childhood is whether young children are included in the range of family and community activities or spend their time segregated in situations created for children. In many Mexican American and Indigenous communities of the Americas, children are broadly and collaboratively included in family and community events (Alcalá et al., 2018; Morelli et al., 2003; Rogoff, 2003; Rogoff & Mejía-Arauz, 2022). This inclusion gives children the opportunity to learn about skills and cultural values by observing and taking part in them and to develop keen attention to surrounding events (Chavajay & Rogoff, 1999; Correa-Chávez & Rogoff, 2009). Rogoff and her colleagues refer to this way of organizing children’s lives as “learning by observing and pitching in” (LOPI) to family and community endeavors (see, e.g., Rogoff, 2014; Rogoff & Mejía-Arauz, 2022). In communities where LOPI is common, mothers have reported that a primary childrearing goal is for young

children to learn to be community minded; children often pitch in to family work and other activities together with other family members (Coppens & Rogoff, 2021; Rogoff & Coppens, 2024). In LOPI, the relations between adults and children are collaborative, and they commonly show mutuality and synchrony (Dayton et al., 2022; Rogoff & Mejía-Arauz, 2022). Community organization that includes or excludes children in the mature activities of the family and community plays a powerful role in children’s early relations with the people in their lives.

COMMUNITY FACTORS

Communities can serve as powerful positive influences on parenting, child development, and early relational health (Belsky & Jaffee, 2015; Garbarino et al., 2006; Garner & Yogman, 2021; Komro et al., 2011). Social networks, cultural traditions, faith-based organizations, and informal systems of support often provide families with essential resources that buffer stress and foster resilience (Bornstein et al., 2022; Byrnes & Miller, 2012; Charlot-Swilley et al., 2024; Holt-Lundstad, 2022; Jarrett et al., 2010; Kana’Iaupuni et al., 2005). Strong community ties can support caregiver well-being; promote positive parenting practices; and offer children consistent models of trust, belonging, and collective identity (Kirmayer et al., 2009; Masten et al., 2023; Ungar, 2011).

Neighborhoods can contribute to conditions that influence parenting practices and children’s developmental trajectories (Burt et al., 2024; Garbarino et al., 2006; McDonell & Sianko, 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Neighborhood assets such as safe public spaces, opportunities for community engagement, access to green space, reliable transportation, and quality local services create supportive environments that foster children’s learning, play, and relational security (Biglan, 2015; Komro et al., 2016; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sakhvidi et al., 2023; Shuey & Leventhal, 2019). At the same time, when neighborhoods lack these resources, such as when families face unsafe environments, limited opportunities for community engagement, reduced access to green space, transportation barriers, or inadequate local services, parents and caregivers can encounter additional challenges in supporting children’s health and well-being (Garbarino et al., 2006; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sellström & Bremberg, 2006; Shuey & Leventhal, 2019; Thorpe et al., 2024). These conditions do not deterministically define family outcomes; rather, they make parenting more difficult and require families to draw more heavily on their resilience and coping strategies (Doty et al., 2017; Easterbrooks et al., 2024; Yoshikawa et al., 2012). Recognizing both the strengths and constraints of communities allows for a more balanced understanding of how context shapes early

relational health, thereby highlighting resilience while also underscoring the importance of improving neighborhood conditions (Ellis & Dietz, 2017).

Neighborhood Factors

An integrative review by Cuellar et al. (2015) examined the association between three overarching neighborhood constructs and parenting: neighborhood disadvantage (socioeconomic deprivation of the area [e.g., limited institutional and economic resources]), neighborhood danger (overall community safety [e.g., crime statistics, fear of crime, exposure to community violence]), and neighborhood disengagement (social and emotional support and social control).

Neighborhood disadvantage, housing instability, and exposure to violence further disrupt family routines and elevate caregiver distress, increasing the risk of less responsive or harsher parenting (Coulton et al., 2007; Gracia et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2019). Neighborhood disadvantage was associated with decreased warmth, higher control (Burt et al., 2023; Gayles et al., 2009; Klebanov et al., 1994), and greater endorsement of threats and yelling as disciplinary practices (Caughy & Franzini, 2005); however, in one review, findings were mixed, with some studies finding no association between neighborhood disadvantage and parenting and other studies observing less supportive parenting in resource-limited contexts (Cuellar et al., 2015). Neighborhood disadvantage can also have a direct impact on child outcomes by increasing children’s exposure to stress and limiting safe opportunities for play and social interactions (Sharkey & Faber, 2014).

Neighborhood danger was also associated with negative parenting practices (Ceballo & McLyod, 2002; Choi et al., 2018; Cuartas, 2018; Cuellar et al., 2015) or fewer positive parenting behaviors (Gonzales et al., 2011; Pinderhughes et al., 2001), with parents engaging in lower levels of warmth and greater behavioral control in the context of higher levels of danger; however, other studies found null associations (Dorsey & Forehand, 2003; Gayles et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2003) or an attenuation of the independent effects of neighborhood danger if socioeconomic disadvantage was added to the model (Burt et al., 2023). A recent meta-analysis (147 distinct studies) found small but significant associations between community violence and positive parenting (r = −.059), harsh/neglectful parenting (r = .133), parent–child relationship quality (r = −.106), and behavior control (r = −.047; Thorpe et al., 2024).

Finally, although less studied, perhaps because of conceptual ambiguity and challenges in measurement, neighborhood disengagement has been associated with parenting styles that are less positive (Cuellar et al., 2015; Dorsey & Forehand, 2003; Vieno et al., 2010); notably, these findings were consistent across family income levels and ethnicity.

These neighborhood exposures are linked to poorer physical health outcomes, including higher rates of asthma, obesity, and sleep problems in young children (Christian et al., 2015; Curtis et al., 2013; Kohen et al., 2008; Sellström & Bremberg, 2006). Importantly, these effects are not only mediated through parents’ stress and caregiving practices (as highlighted above) but also directly experienced by children, who navigate peer networks, schools, and play spaces within their communities. Exposure to unsafe or socially disorganized neighborhoods is associated with more internalizing problems (Beyer et al., 2024; Caughy et al., 2008) and externalizing behaviors (Chang et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2019; Li et al., 2017) in childhood.

Neighborhood social processes, including collective efficacy, can buffer these risks and foster resilience, ensuring that children develop within relationally supportive contexts, even in under-resourced areas (see more below). Additionally, the built environment and the availability of transportation services can support or hinder early relational health.

Neighborhood social cohesion and collective efficacy (trust and closeness among neighbors) also reduce parental stress, are protective factors against child maltreatment (Abdullah et al., 2020; Hong et al., 2023; Maguire-Jack & Wang, 2016; Pei et al., 2022), and likely promote early relational health. Collective efficacy goes beyond general notions of social capital by emphasizing relational processes such as intergenerational closure (connections across generations that support child-rearing), mutual exchange (reciprocal assistance among families), and informal social control and support (Cook, 2014; Sampson, 2001; Sampson et al., 1999). These dynamics provide scaffolding for positive parenting and child safety and well-being, and they create environments in which children can thrive despite socioeconomic challenges (Abdullah et al., 2020; Molnar et al., 2016; Odgers et al., 2009; Sampson, 2001).

Collective efficacy was first linked to protective effects on child development and community safety in a study of Chicago neighborhoods by Sampson et al. (1999), where higher levels of collective efficacy were associated with lower rates of violence and improved child outcomes, even in resource-constrained settings (see also Sampson et al., 1997). Applied to early relational health, these findings suggest that communities characterized by strong networks of trust and reciprocal support not only buffer children from risks but may also actively promote sensitive, responsive caregiving relationships (Davis et al., 2017; Garbarino et al., 2006; Hargreaves et al., 2017; Shuey & Leventhal, 2019).

Transportation Services and the Built Environment

The availability of safe outdoor spaces and child-friendly infrastructure and access to services and supports such as childcare, health care, and early

education promote child development and positive parenting (Buthman et al., 2025; Garbarino et al., 2006; Villanueva et al., 2016) and protect children in high parental stress contexts from risk of child maltreatment (Maguire-Jack & Showalter, 2016).

Access to essential services is linked to the availability of reliable and affordable transportation. Transport poverty is a “hidden crisis” affecting approximately 25% of U.S. adults, with those living in poverty most likely to experience transportation insecurity (53%; Murphy et al., 2022). It is an important yet relatively understudied social determinant of health, as it enables access to school, work, and important daily activities (MacLeod et al., 2022) and has implications for child well-being (Waygood et al., 2017). Access to reliable, affordable transit may enhance early relational health by connecting caregivers and children to essential services (Atherton et al., 2021; Riley et al., 2021; Rozynek, 2024), thereby indirectly reducing stress and supporting sensitive parenting. In contrast, transportation barriers contribute to caregiver isolation, diminished well-being, restricted access to necessary services and early care and education (Currie & Delbosc, 2011; Garg et al., 2022; Maxwell & Thomas, 2023; Paige & Wagner, 2024), and more limited employment opportunities.

For young children, transportation and the built environment directly shape continuity of medical care, nutrition, and learning opportunities (Abdollahi et al., 2023; Waygood et al., 2017). Families without reliable transportation are more likely to miss pediatric appointments, leading to increased likelihood of gaps in preventive care such as immunizations and developmental screenings (Park et al., 2025; Syed et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2006). Transportation barriers are also linked to increased food insecurity, which affects children’s physical health and growth (Semborski et al., 2025). Beyond these health impacts, long commutes can limit time for family interaction (Bai et al., 2021; Denstadli et al., 2017; St. George & Fletcher, 2012) and may also reduce children’s opportunities for participation in extracurricular or early learning programs (Hopson et al., 2024; Meier et al., 2018; Paige & Wagner, 2024).

As a component of the built and natural environment, green space plays an important role in supporting healthy development and family functioning. In urban contexts, green space is a key neighborhood feature that includes publicly accessible areas with vegetation, such as parks, playgrounds, and community gardens, that offer children and families opportunities for physical activity, social interaction, and mental restoration, all of which support healthy development and family well-being (McCormick, 2017).

Research in the United States, including urban cohort studies, demonstrates that residential green space is linked to improved child physical activity and mental health (Fyfe-Johnson et al., 2021). Access to green space has significant direct effects on children’s physical, mental, and social-emotional health and cognition (Liao et al., 2019; Odgers et al., 2012; Sakhvidi et al.,

2023). Regular exposure to parks, gardens, and natural environments is associated with increased physical activity, lower risk of obesity, improved sleep quality, and enhanced immune functioning in children (Andersen et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2019, 2021; Manandhar et al., 2019; Markevych et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2025). Green space also promotes stress reduction and supports emotion regulation (Ríos-Rodríguez et al., 2024), with studies showing that children who spend more time in nature exhibit fewer internalizing problems (Towe-Goodman et al., 2024) and externalizing behaviors, in particular hyperactivity and inattention problems (Vanaken & Danckaerts, 2018). Importantly, access to green space provides settings for exploration, imaginative play, and social interaction, all of which foster peer relationships and strengthen caregiver–child bonds through shared outdoor activities (Chawla, 2015).

MACRO-LEVEL FACTORS

Macro-level social determinants of health operate through pathways similar to those described by the Family Stress Model (Masarik & Conger, 2017), in which structural and contextual disadvantages can increase caregiver stress and psychological distress, which in turn may disrupt parenting practices and compromise the nurturing relationships that are foundational for early relational health. The sections below describe macro-level factors such as climate and extreme weather events, technology and digital environments, and racism and other discrimination.

Climate and Extreme Weather Events

The environment and climate can influence children’s early relational health through dangers such as the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as wildfires, floods, hurricanes, and heatwaves, but also more gradual and subtle shifts, including rising sea levels, prolonged droughts, altered growing seasons, and declining livability (see, e.g., Perera, 2022). These act as a threat multiplier through numerous intersecting pathways to disrupt ecosystems and human systems, contributing to economic strain, greater disease burden, increased mortality, forced migration, and biodiversity loss (Abbass et al., 2022).

A growing body of evidence shows that climate change and resulting extreme weather events are already affecting the development of children and adolescents adversely (Cuartas et al., 2024; Helldén et al., 2021; UNICEF, 2021; Vergunst & Berry, 2022). Environmental disruptions present significant challenges to parents’ capacity to safeguard and nurture their children (Sanson et al., 2018). Cuartas and Vergunst (2025) outlined several ways that extreme weather events can undermine access to basic needs by damaging or destroying infrastructure; disrupting access to essential services, food, and

clean water; and potentially leading to school closures and family separation or forced displacement. Losing a home to floods, wildfires, or tornados not only results in the loss of material resources but also compromises the foundations needed to provide safe, stable, and nurturing care. These highly stressful circumstances can impair caregivers’ mental health (Cianconi et al., 2020), increase the risk of inadequate supervision, reduce responsiveness and sensitivity, and heighten the likelihood of child maltreatment and intimate partner violence (Cuartas, Bhatia, et al., 2025; Cuartas, Ramírez-Varela, et al., 2025; Sanson et al., 2018; van Daalen et al., 2022). Such events place considerable strain on parents’ capacity to respond and adapt, undermining their ability to implement the essential skills for fostering early relational health when their safety, well-being, and resources are severely constrained.

Technology and Digital Environments

While digital technology can offer benefits, excessive or poorly managed screen use can disrupt the development of early relational health. Research indicates that parental technoference—interruptions in caregiver–child interactions due to digital devices—is associated with reduced responsiveness, fewer verbal exchanges, and diminished emotional attunement (McDaniel & Radesky, 2018a,b). Even brief attentional shifts caused by smartphones can interrupt the interactions that are critical for language, emotional regulation, and social development (Harvard Center on the Developing Child, n.d.).

For children, high screen exposure in infancy and early childhood is linked to delayed language acquisition, reduced social skills, and increased behavioral difficulties (Madigan et al., 2019). Passive media use often replaces interactive play and shared exploration, which are central to early relational health (Radesky & Christakis, 2016). Parents’ increased technology use in their child’s presence has been associated with less secure attachments among young children ages birth to 4.9 years (see Toledo-Vargas et al., 2025, for meta-analysis).

Importantly, technology usage does not need to be eliminated; it can be managed to preserve relational quality. Family media plans, tech-free routines (e.g., during meals, bedtime), and intentional co-viewing can help ensure screens support rather than supplant caregiver–child connection (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2016). Preserving early relational health in the digital age requires balancing the benefits of technology with the irreplaceable role of in-person, emotionally responsive caregiving and shared early learning experiences.

Cultural Connectedness

Having a sense of pride, belonging, mattering, appreciation for, and engagement with one’s group irrespective of the perceptions of others—that

is, a sense of cultural connectedness—can be a significant protective factor for early relational health. Numerous studies have shown that having a strong sense of cultural connectedness helps to mitigate the negative impacts of racism-related stress; provides children with a sense of rootedness by enhancing their sense of self, self-esteem, and self-worth; and strengthens relationships within families and social networks within communities (e.g., Birman & Simon, 2014; Edwards & Romero, 2008; Henson et al., 2017; Iwamoto & Liu, 2010; Lucero, 2014; Mossakowski, 2003; Neblett, 2023; Sellers et al., 2006; Tribal Information Exchange of the Capacity Building Center for Tribes, 2023).

Research shows that immigrant families often draw on cultural traditions, kinship networks, and intergenerational caregiving that can support resilience and early relational health (Cabrera et al., 2022; Ceballos & Palloni, 2010; Leyendecker et al., 2018; Motti-Stefanidi, 2018). For example, Mexican immigrant families have been shown to demonstrate strong cultural practices that support maternal and infant health, even amid socioeconomic disadvantage (Ceballos & Palloni, 2010). For children, these cultural and relational resources are associated with positive socioemotional development, stronger identity formation, and reduced behavioral risks despite socioeconomic challenges (Leyendecker et al., 2018; Motti-Stefanidi, 2018). At the same time, immigrant families may encounter unique challenges, including language barriers, social isolation, precarious work conditions, and potential risks of family separation, all of which can elevate stress and limit access to supportive services, thereby affecting parent–child interactions (Eltanamly et al., 2023; Khalil et al., 2025; Stewart et al., 2015).

Conversely, racism and other discrimination can negatively impact early relational health. The recently proposed Minority Family Stress Model (Li & Zhou, 2025) describes how families with minority status experience both distal stressors (e.g., prejudice, discrimination, institutional barriers) and proximal stressors (e.g., expected social rejection, concealment of identity) that affect family functioning, relational outcomes, and individual mental and physical health. For example, scholars describe how interpersonal and system-level racism and discrimination can heighten parenting stress and reduce caregiver responsiveness, which can contribute to chronic stress in children (Center on the Developing Child, 2020; Condon et al., 2022; Zong et al., 2023).

Exposure to racial bias in caregiving and educational contexts can also have measurable effects on children’s health and relational outcomes. Evidence shows that children who directly experience or even indirectly observe racism are at increased risk for stress-related physiological responses, poorer socioemotional functioning, and diminished relational security (Heard-Garris et al., 2018; Priest et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2019). Early care and education settings are especially important, as they provide daily opportunities for children to observe adult–adult and adult–child

interactions. In these contexts, Meltzoff and Gilliam (2024) show that the modeling of behaviors becomes a powerful pathway through which social group biases may be embedded in children’s relational experiences (see also Zhang et al., 2024).

Studies have found multiple physical, emotional, and behavioral effects from experiencing, witnessing, or being fearful of racism, including early in childhood (Berry et al., 2021). For example, mothers’ experiences of discrimination during pregnancy predicted greater inhibition/separation problems and more negative emotionality in their infants at ages 6 months and 1 year (Rosenthal et al., 2018). Similarly, greater cumulative family discrimination and acculturation stress from pregnancy to 24 months postpartum predicted more mother intrusiveness and less mother sensitivity during an observational free play task at 36 months postpartum (Zeiders et al., 2016). Other effects of racism include nighttime sleep disturbances (Yip et al., 2020); heightened stress, which creates elevated blood pressure and a weakened immune system; diminished hope, motivation, self-confidence, and resilience; stereotype threat; negative racial identity (Lewsley, 2020); and suicidal ideations (Madubata et al., 2022). According to the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2020),

Years of scientific study have shown us that, when children’s stress response systems remain activated at high levels for long periods, it can have a significant wear-and-tear effect on their developing brains and other biological systems. This can have lifelong effects on learning, behavior, and both physical and mental health. A growing body of evidence from both the biological and social sciences connects this concept of chronic wear and tear to racism. This research suggests that constant coping with systemic racism and everyday discrimination is a potent activator of the stress response. [. . .] Multiple studies have documented how the stresses of everyday discrimination on parents or other caregivers, such as being associated with negative stereotypes, can have harmful effects on caregiving behaviors and adult mental health. And when caregivers’ mental health is affected, the challenges of coping with it can cause an excessive stress response in their children. (p. 1)

Families may face other challenges as well. Gendered expectations often place a disproportionate caregiving burden on mothers, increasing their risk for stress and depression, which can undermine sensitive and attuned caregiving (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2020). Families with disabilities contend with ableism, which can lead to experiencing exclusion, stigma, and discrimination, alongside a lack of support from extended family, community, and/or professionals; these experiences create additional stressors for families (Li et al., 2024; Neely-Barnes et al., 2010). Goldberg and Smith (2011) reported that families headed by a sexual minority parent (or parents) can be

affected by stigma, which can affect parents’ mental health and relationship functioning (see Song et al., 2024, for meta-analysis), with potential downstream effects on their young child and caregiving relationships (see also Farrell et al., 2017). These broad social structures and inequalities become embedded in the everyday relational experiences of caregivers and young children, shaping early relational health in profound and enduring ways.

Notwithstanding the multiple negative impacts of racism and other discrimination on child development, positive child outcomes are nonetheless possible—and common—due to the nurturing and protective experiences many Black, Native American, Latine, and Asian American children receive in their relational contexts, particularly in their families and cultural communities, as noted above.

CONCLUSION

Early relational health is shaped by a constellation of interconnected individual, relational, and systemic factors that operate across time and context. At the individual level, both parent/caregiver and child characteristics shape early relational health. Parents’ attachment histories, mental health (e.g., depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance use), and emotion-regulation skills are linked to the quality of caregiving and child attachment. The behaviors of parents/caregivers, including sensitivity, responsiveness, and mentalization, are strongly predictive of secure attachments, even during the prenatal period. Children’s temperaments and health conditions also interact with caregiver attributes and environmental stressors to influence early relational health.

Relationally, dynamics within family systems—such as couple and coparenting relationships—demonstrate significant associations with early relational health. Conflict, intimate partner violence, and poor coparenting undermine secure attachments, while cooperation and social support bolster positive relational health. Siblings, grandparents, and broader social networks further contribute to children’s social-emotional development and early relational health. Attention to cultural variation in the dynamics of family systems is an important task for future research.

Resource and community-level influences—including economic security, food and housing stability, neighborhood conditions, and access to green space and transportation—can also shape early relational health. Macro-level social drivers of health and structural and contextual disadvantages can increase caregiver stress and psychological distress, which in turn may disrupt parenting practices and compromise the nurturing relationships that are foundational for early relational health. Cultural connectedness, strong community ties, and resilience within families can buffer negative effects.

A key finding of this chapter is that early relational health is shaped by many sources of influence, including the individuals, familial and community relationships, community organization and systems, public policy, and social and environmental characteristics. These influences do not operate in isolation; rather, they are interactive and reciprocal, continually shaping one another in dynamic ways. Their synergistic interplay means that the combined impact is greater than the sum of individual factors, making early relational health the product of complex, evolving relationships across multiple levels of influence. The next chapter builds on the understanding of these influences to inform interventions that can enhance early relational health and, ultimately, improve children’s long-term outcomes.