Early Relational Health: Building Foundations for Child, Family, and Community Well-Being (2025)

Chapter: 4 Supporting Early Relational Health in Early Childhood Systems

4

Supporting Early Relational Health in Early Childhood Systems

Chapter Highlights

- Framing early relational health as a shared community responsibility encourages multisector strategies that promote, protect, and restore relational well-being across the lifespan.

- An early relational health approach that attends to the needs of every child and family requires an asset-based frame that recognizes and nurtures the strengths families possess, including those rooted in family, community, and cultural perspectives.

- Promoting early relational health begins with both understanding a child’s strengths and relational needs and understanding and supporting the caregiving capacity of the adults, families, and communities in relationship with them.

- Systems, programs, and initiatives that promote early relational health need to create the conditions and contexts that facilitate connections at multiple levels: interpersonal, familial, community, and societal.

- Research and practice are strengthened by listening to family and caregiving voices, experiences, and perspectives and building on them for understanding early relational health.

As described in the previous chapters, early relational health develops over time in moments of connection; manifests in person-, family-, and community-specific ways; and is influenced by complex, evolving relationships across many ecological levels. This includes, but is not limited to, relationships involving family members; early childcare educators; other significant adult relationships in the community; the parent’s workplace and the economy; digital media; and the norms and values embedded in cultural practices and local, state, and national policies. Understanding the development of early relational health and its multiple levels of influence offers insights into potential levers for supporting early relational health. Early relational health promotion efforts can (a) support the time and resources parents and caregivers need for building moments of connection in daily living and building healthy relationships across ecological levels (individual, familial, community, and societal); (b) invest in family-driven, culturally attuned, and community-based programs to ensure that solutions are appropriate for and accessible to all families and communities; and (c) strengthen tiered, system-level supports across sectors, including universal promotion efforts.

This chapter describes a public health framework for supporting early relational health. The framework includes universal promotion across settings (e.g., health care, childcare and early education, family support services, formal and informal community contexts). Next, it reviews the available evidence from family engagement and place-based initiatives and offers several practices that can guide efforts to advance early relational health across early childhood systems. In doing so, it emphasizes the critical role of family leadership in co-designing the development and implementation of family support models and systems. Finally, gathered from the committee’s review and expert testimony, the chapter describes examples of existing approaches and programs aligned with a public health framework that support early relational health across ecological levels, tiers, and sectors.

PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH

A public health approach to early relational health recognizes that supporting healthy relationships is not the sole responsibility of caregivers, clinicians, or early childhood educators; rather, it is a systems-level imperative with profound developmental and economic consequences. As Garner and Yogman (2021) argue, early relational health can be viewed as a public good and a vital component of population health. Framing early relational health as a shared responsibility allows for multisector strategies for promoting, protecting, and restoring relational well-being across the lifespan, starting in early childhood. Put another way, early relational health is promoted when the many systems that interface with children and

their families are all aligned in providing a wide range of trusted, accessible, and family-led resources that support parents and caregivers as they meet not only the physical but also the social-emotional needs of their children.

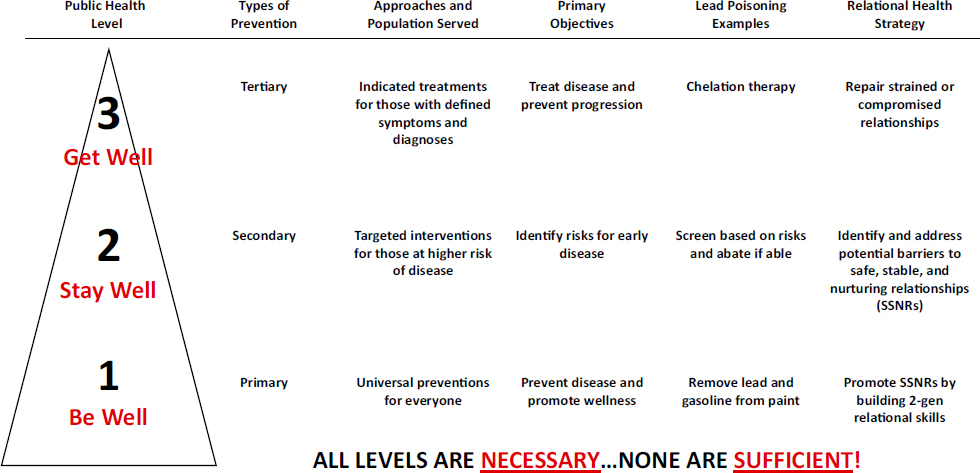

A public health approach is grounded in universal primary preventions, going beyond the biomedical approach to disease, which is grounded in screens for risk factors (secondary preventions) and utilizing evidence-based treatments (tertiary preventions). The traditional biomedical model of disease is primarily focused on “what is wrong with you” (Garner, 2016). In contrast, according to the American Public Health Association (APHA, 2019), “public health promotes and protects the health of people and the communities where they live, learn, work, and play,” and involves both changing behaviors and “assuring the conditions in which people can be healthy” (p. 1).

For example, the public health approach to preventing lead poisoning is grounded in universal primary prevention approaches such as abating lead from paint and gas. Because those universal primary preventions are not perfect, a public health approach also utilizes screening for lead poisoning based on a patient’s risk factors (e.g., age, zip code, year the home was built, potential occupational exposures). For those who are symptomatic or known to have high lead levels, chelation therapy is an available evidence-based treatment. The more effective the universal primary preventions and targeted secondary preventions are, the less often the indicated tertiary preventions will be needed. Vertical integration of primary, secondary, and tertiary preventions is necessary because all three levels are needed but none is sufficient on its own to address the multifactorial public health issue of lead poisoning.

Primary prevention promotes early relational health and mitigates risks before they occur. Examples include public awareness campaigns, policies that increase time for connection (e.g., paid family leave, living wage), and community design that fosters connection (e.g., accessible parks, family spaces).

Secondary prevention targets emerging signs of or risk factors for relational stress and includes strategies such as home visiting programs that identify early concerns and offer support.

Tertiary prevention addresses chronic or entrenched relational disruption. This includes interventions such as dyadic mental health services (e.g., Child–Parent Psychotherapy [CPP], Parent–Child Interaction Therapy), caregiver support groups, infant-toddler court programs, and trauma-informed systems for families affected by adversity.1

___________________

1 Trauma-informed principles and practices support reflection in place of reaction, curiosity in lieu of numbing, self-care instead of self-sacrifice, and collective impact rather than siloed structures (see, e.g., Bloom, 2012).

Assessing the existing efforts to promote early relational health through a vertically integrated public health lens reveals that current efforts are upside down (see Figure 4-1). Instead of devoting most attention to primary prevention of problems in early relational health—that is, promotion of early relational health—many current efforts lie in the few available, time-intensive, costly, dyadic-based treatments to repair relational health (tertiary prevention; Bjorseth & Wichstrom, 2016; Dozier & Bernard, 2017; Lieberman et al., 2006). There is also a burgeoning effort to screen for known risks to relational health, such as adverse childhood experiences or the social drivers of poor health (Austin et al., 2024; Erickson et al., 2024; Estrada-Darley et al., 2024; Luckett et al., 2025). The universal primary preventions that promote early relational health, such as time and resources to support shared activities such as play, reading aloud and storytelling, walks outdoors, and other positive childhood experiences, receive little attention or investments from practitioners or policymakers (Bethell, Gombojav, & Whitaker, 2019; Bethell, Jones, et al., 2019; Sege, 2024; Yogman et al., 2018; Zuckerman & Khandekar, 2010). A public health approach to early relational health would also require integration vertically, horizontally, and longitudinally across service sectors (Halfon et al., 2007).

Informed by understanding the biological and psychological mechanisms (described in previous chapters) that foster childhood experiences,

NOTE: This figure shows the classic public health pyramid, with examples from each level for lead poisoning prevention and relational health promotion. The emphasis of current efforts inverts the pyramid, with broader efforts at level 3 and increasingly narrow emphasis on level 2 and then level 1 (primary prevention of problems).

SOURCE: Adapted from Garner & Saul, 2025.

both positive and negative, the committee emphasizes the need for proactive primary prevention efforts to support positive outcomes for all children. Actively promoting positive development through strategic universal investments is the base of the classic public health pyramid. However, universal primary preventions are not at odds with targeted interventions or treatments. Applying a public health lens integrates these efforts into a comprehensive and coherent approach that not only prevents problems but also promotes positive development (see, e.g., Garner & Saul, 2025).

Public health strategies for advancing early relational health need to clarify roles and responsibilities across systems, including which entities lead universal promotion efforts and which support families with emerging needs, as well as how intensive supports are accessed and sustained. Framing early relational health from a public health approach positions early relational health as both a societal resource and a systems-level responsibility. Taking this approach emphasizes that relationship-centered development is not just the work of individual caregivers or pediatricians—it becomes part of the social fabric and policy architecture that shapes community life.

The Health Outcomes from Positive Experiences (HOPE) framework, developed by Robert Sege and his colleagues, complements the socioecological model outlined in Chapter 3 and the public health framework, emphasizing the protective role of positive childhood experiences in fostering early relational health (HOPE, n.d.; Sege & Harper Browne, 2017). The HOPE framework is informed by three core principles: First, child health is shaped by both positive and negative influences across the entire ecosystem; thus, the interplay of factors such as family supports, community networks, environmental exposures, and the social determinants of health needs to be identified and addressed. Second, the well-being of children and their caregivers is interdependent; as such, the promotion of positive experiences needs to simultaneously support child development, caregiver health, and the quality of the parent–child relationship. Third, child health is conceptualized as multidimensional, encompassing physical, cognitive, emotional, and social domains. By recognizing how multiple contexts interact to shape child development, the HOPE framework promotes policies and practices that strengthen protective factors and address system-level barriers (Sege & Harper Browne, 2017).

According to the HOPE framework, protective childhood experiences can be organized into four interrelated domains that reflect and operationalize its core principles (Sege & Harper Browne, 2017). One domain centers safe, stable, protective, and equitable environments, recognizing that healthy development depends on consistent housing, nutritious food, adequate sleep, opportunities for learning and play, and access to high-quality medical and dental care. A second domain emphasizes constructive social engagement and connectedness, including participation in social and cultural institutions, joyful activities, personal achievement, cultural

identity, and a sense of belonging. The third domain focuses on nurturing and supportive relationships, such as secure attachments, responsive caregiving, and trusting relationships with peers and adults. Finally, the domain of social and emotional competencies encompasses learning skills such as emotional regulation, executive function, self-awareness, social cognition, and adaptive coping. Table 4-1 provides an overview of the three HOPE guiding principles, with the four domains of positive childhood experiences.

TABLE 4-1 Positive Childhood Experience Domains Aligned with HOPE Framework Principles

| HOPE Guiding Principle | Domain of Positive Childhood Experiences | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive and negative influences on child health operate across the social ecology. | Safe, stable, protective, and equitable environments | Consistent and safe environments that support children’s physical and developmental needs within broader social and environmental contexts. | Safe housing, nutritious food, adequate sleep, access to medical and dental care, opportunities for play and learning. |

| Constructive social engagement and connectedness | Opportunities for participation in supportive social and cultural settings that foster belonging and identity. | Involvement in social institutions, joyful activities, experiences of success, cultural awareness, feeling valued. | |

| 2. Child and caregiver well-being are interconnected. | Nurturing and supportive relationships | Emotionally secure and responsive relationships that promote mutual well-being and strong parent–child connections. | Secure attachments, warm caregiving, mentally and physically healthy caregivers, trusting peer and adult relationships. |

| 3. Child health is multidimensional, encompassing physical, emotional, cognitive, and social domains. | Social and emotional competencies | Development of skills essential to self-regulation, resilience, and social functioning across developmental domains. | Emotional and behavioral regulation, executive function, social awareness, adaptive responses to stress. |

NOTE: HOPE = Health Outcomes from Positive Experiences.

SOURCE: Adapted from Sege & Harper Browne, 2017.

KEY PRACTICES THAT ADVANCE EARLY RELATIONAL HEALTH IN EARLY CHILDHOOD SYSTEMS

Early relationships prosper through positive and responsive everyday interactions, such as during caregiving; the shared routines of mealtime, carpooling and bus rides, bathing, bedtime, and reading aloud and storytelling; and freeform conversations. Over time, experiences like these envelop and nurture relationships and grow strong roots of connectedness (Li & Ramirez, 2023).

Early relational health is further supported through connections to other people in children’s communities by rituals and traditions that create spaces for additional social experiences grounded in cultural wisdom and values. When these foundational anchors of connection are not honored by service delivery systems, families and children often experience feelings of distrust, disrespect, disconnection, and threat, as the services may feel misaligned with their lived experiences and may contribute to high rates of families not engaging or leaving programs (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2015). Lacking such respect, maintaining a sense of connection and emotional attunement thus becomes ever more challenging to sustain engagement and participation (Bruner, 2021; Charlot-Swilley et al., 2024; Dumitriu et al., 2023).

The committee—drawing from the research literature on family engagement and place-based initiatives, perspectives from scholars and practitioners, and its expert knowledge—identified five key principles for embedding early relational health in early childhood systems:

- Co-design local solutions and services with family participation in a way that is community driven and culturally specific. Families and communities have many strengths that can help build and sustain early relational health. Their capacities and resources are as wide ranging and varied as the families and communities themselves. Their adaptive approaches to building relationships against all odds can take on many forms, reflecting the principle of “universality without uniformity” (Li & Zaentz, 2025; Mesman et al., 2018). Co-designing supports with families, rather than delivering services to them, promotes greater alignment with community priorities, honors cultural values, and strengthens trust, which leads to more equitable and sustainable results for children and families. Partnerships with families and communities in system-building are key.

- Prioritize relationship-building and relational practices within program design for family support programs and systems and implementation and improvement science. Family support programs and

- systems can prioritize relationship-building and relational practices as an integral component of program designs. Implementation and evaluation studies can focus on integrity of implementation rather than assessing implementation fidelity exclusively; this way, program designs can focus on doing what matters most while accommodating local needs and circumstances (Li & Zaentz, 2025; Waters & Anderson, 2025).

- Provide sustainable reflective supervision and practices, including reflective video feedback, to practitioners at all levels and in all sectors of the early childhood system. Implementing reflective supervision and practices across the service-sector ecosystem can enable relationship-centered care for practitioners, providers, and families (Heller & Gilkerson, 2009). Similarly, reflective video feedback for families within family support programs is a promising approach for advancing early relational health (e.g., PlayReadVIP, Infant Mental Health-Home Visiting).

- Adopt a relational abundance and positive family assets mindset using relationally focused, healing-centered practices for communities. Relational abundance means that all communities and neighborhoods have people and organizations who can offer relational supports. An asset-based mindset recognizes and nurtures families’ strengths, including those rooted in cultural and generational wisdom (Waters & Anderson, 2025). Combined with the “funds of knowledge” construct, it is understood that families bring rich historical, cultural, social, and cognitive knowledge and skills that children and families carry from their homes and communities (González et al., 2006; Vélez-Ibáñez & Greenberg, 1992). The lived experiences of families and the practitioners who care for them, as well as their cultural traditions and community-based wisdom, offer insight into what children and families need to grow, be healthy, and flourish.

- Strengthen and sustain family leadership infrastructures in communities. Sustained transformation requires support for family leadership pipelines, community-rooted organizations, and the infrastructure needed for long-term collaboration and power-sharing and supporting family and community self-determination (Gehl et al., 2020).

Early childhood systems can support families’ and communities’ efforts to build early relational health. Developing systems that promote early relational health and support community flourishing requires shifting from transactional service delivery to transformative relational partnerships (Ginwright, 2022). The process demands deep listening to families

and developing trust between sectors while grounding care in cultural wisdom and personal experiences. In addition, children and families who face system-level challenges or those who care for children with disabilities succeed best when their surrounding communities establish connection-based support systems that respect dignity and share power. The sections that follow describe these key practices for embedding early relational health within early childhood systems in detail.

1. Co-Design Local Solutions and Services with Family Participation in a Way That Is Community Driven and Culturally Specific

Geographically grounded, cross-sector collaborations can integrate family leadership into childhood systems effectively, to the benefit of children and families. Although difficult to replicate, scale, and spread, several place-based initiatives show the effectiveness of co-designing supports with families rather than delivering services to them (e.g., Harlem Children’s Zone, Magnolia Community Initiative, and the Family Resource Centers movement; Croft & Whitehurst, 2010; Gehl et al., 2020). This approach promotes greater alignment with community priorities, honors cultural values, and strengthens trust locally, which can lead to greater family participation, engagement, and more equitable and sustainable results for children and families (Benz et al., 2024; Early Childhood Learning and Innovation Network for Communities, 2019; National Association for the Education of Young Children, n.d.; Urban Institute, n.d.). Box 4-1 includes illustrative perspectives from parents and caregivers who shared with the committee their insights on efforts to advance early relational health.

This broader ecological framing calls practitioners and systems to approach relational development with cultural context in mind and with cultural humility (Tervalon & Murry-Garcia, 1998). Cultural humility invites practitioners to slow down and listen with compassionate curiosity and openness while creating space for colearning and discovery with families and communities. The Mi’kmaq principle of Etuaptmumk, or Two-Eyed Seeing (Marshall, 2004), promotes an integrative or relational worldview and embraces interdependence, complexity, and multiple ways of knowing (see also Rosado-May, 2016, on intercultural learning). Etuaptmumk refers to learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing, and learning to use both these eyes together for the benefit of all. Etuaptmumk is the gift of multiple perspectives treasured by many Aboriginal peoples (Marshall, 2004; Wieman & Malhotra, 2023).

Co-designing solutions and services with families and communities honors the expertise that communities hold about their children’s needs

BOX 4-1

Parent/Caregiver Perspectives

Parents who serve as leaders in the Nurture Connection Family Network Collaborative shared their perspectives on the most important things that can be done to support families as they build and strengthen positive, nurturing relationships (Nurture Connection, n.d.). These parent leaders emphasized the importance of building trust between families and systems within their communities, such as the health care system and various community services. In addition, they pointed to the impact that external stressors can have on parents, and on their children as a result:

“These are the three most important things we can do to support parents and caregivers at the community level so they can better connect with their babies and toddlers:

- Advocate for the services families need.

- Develop and deliver those programs based on families’ needs while respecting and acknowledging their strengths as the most competent caregivers to ensure their children’s well-being.

- Partner with community resources that can meet the families where they are at such as healthcare centers, daycares, libraries, churches, laundromats, etc. These partners are very important in facilitating the information that supports the emotional connection between them and providing the opportunity for the families to practice what they’ve learned.”

“When a family knows they have medical insurance for both the mother and baby for the first year of life, it allows them to feel more peaceful. Not having insurance after the baby is born could impact your family finances and potentially your child’s access to medical care, adding additional stress for the family. Relationships shouldn’t depend on having insurance, but the impact can affect their well-being.”

“The best way for a doctor to promote ERH [early relational health] is by living it and demonstrating the importance of building emotional connection in the way you listen and talk to the families you serve. Do you want to encourage parents and caregivers to find everyday moments to emotionally connect with their babies? Role model it for the families. Never underestimate the power of your actions when you are a trusted partner with the families you serve.”

while positioning practitioners, whether they are community members or external partners, as collaborative facilitators who support the activation of existing community and cultural strengths and resources. Supporting a child’s relational health through a culturally informed early relational health lens means adopting a relational abundance mindset and engaging others such as aunties, grandparents, neighbors and friends, community elders, and religious and cultural networks as essential partners. This collaborative model has been demonstrated in home visiting programs (Hiratsuka et al., 2018), Head Start (Barnes-Najor et al., 2019; Sarche et al., 2020), or early care and education more broadly (Gilliard & Moore, 2007).

2. Prioritize Relationship-Building and Relational Practices Within Program Design for Family Support Programs and Systems and Implementation and Improvement Science

Prioritizing relationship-building and relational practices as the integral component that holds together the rest of the programming (parenting curricula, developmental assessments, goal-planning, family participation) is needed to advance early relational health. Such an implementation philosophy for program service and delivery would emphasize being nimble and flexible so that programs can be tailored to meet the needs of families and communities without losing core components of the model or program (Li & Zaentz, 2025; Waters & Anderson, 2025). For example, Wesner et al. (2025), in the context of Indigenous families, suggested that programs pursue such integrity by (a) relationship-building and broadening parent-centric services by including other family members such as grandparents, (b) intentionally supporting and creating a sense of community among participants, (c) adding an intergenerational lens to services, and (d) emphasizing to children and families their connections to their lands and place (p. 128).

This requires carefully considering the specificities of distinct contexts rather than erroneously assuming generalizability and universality across contexts and communities (Berwick, 2008). Complex, multicomponent, social, and system-level interventions can be sensitive to influences such as leadership, changing environments, and organizational history. Yet, program designers, implementers, and researchers have often focused on ensuring fidelity of program implementation. Efforts to ensure fidelity typically involve applying tools and procedures in the process of program implementation to ensure that implementers replicate programs exactly as they were designed and intended. In addition, they may test the average effects of an overall activity on a range of outcomes across all participants (Bornstein et al., 2022; Shonkoff, 2017).

This issue is especially important for complex social and system

interventions. Pawson and Tilley (1997) suggested evaluation models that determine whether programs work (have successful outcomes) by understanding whether they introduce the appropriate ideas and opportunities (mechanisms) to groups in the appropriate social and cultural conditions (contexts). Such models prioritize knowing why a social program works rather than solely whether it works. According to Berwick (2008), evaluators and implementors can use lessons from improvement science to gain and share information on both the ways in which specific social programs produce social changes and the local conditions that could be relevant to the outcomes of interest.

Home visiting provides an example. Programs qualifying for funding are based on meeting defined criteria for “evidence of effectiveness”; yet, as states adopt tiered service models and consider universal approaches, it becomes increasingly clear that evidence for effectiveness and fidelity alone cannot ensure success when implemented at scale. Further consideration is needed of what it means for home visiting to be “evidence based” and how models can be implemented with both rigor and responsiveness in diverse community contexts.

As highlighted below, the evidence for home visiting programs has often been defined through research designs emphasizing internal validity (e.g., randomized controlled trials as the gold standard; Hariton & Locascio, 2018) and strict fidelity of implementation (adherence to protocols, curricula, and dosage; Fixsen et al., 2005), with less attention paid to external or ecological validity (Solomon et al., 2009). While these standards support consistency, they can limit adaptations needed to address family needs, cultural contexts, or workforce realities when implemented across diverse community settings (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). A complementary approach is implementation with integrity (not just fidelity to the original plan), which focuses on preserving core mechanisms of change (e.g., building relational trust, promoting sensitive caregiving) and active program ingredients while allowing flexibility in delivery. Achieving an appropriate balance between fidelity and integrity is important for successful implementation and may be central to addressing continual recruitment and retention challenges. Despite the recognized need for this balance, a persistent discord exists between these orientations (Chambers, 2023; Chambers & Norton, 2016; Fixsen, 2025). Further research is needed to clarify how best to achieve this balance.

These tensions highlight a core challenge for the field, such as in federally directed funding toward programs that are validated through rigorous research (e.g., the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program [MIECHV]) and the realities of practice. The Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation underscored the challenge of scaling evidence-based models, documenting persistent enrollment difficulties, with close to 60% of families receiving at least 50% of intended visits expected

by their model (Duggan et al., 2018). Such findings demonstrate some of the practical limits of scaled implementation. Moving forward, home visiting research and policy can strive for a balance between maintaining program effectiveness and supporting implementation with integrity to local values, needs, and circumstances. This involves identifying the active ingredients that anchor interventions in evidence, while also facilitating culturally responsive and contextually appropriate adaptations. Research agendas will need to expand beyond internal validity to give greater attention to external validity, sustainability, and opportunity and access for all—for example, employing mixed-methods and community-partnered approaches to better understand how, for whom, and under what conditions interventions work. This is necessary not only for improving the evaluation of programs but also for designing effective programs.

3. Provide Sustainable Reflective Supervision and Practices, Including Reflective Video Feedback, to Practitioners at All Levels and in All Sectors of the Early Childhood System

Reflective practice and supervision can support the work of the early childhood workforce2—clinicians (including pediatricians), early care and education providers, and community health workers (including doulas, home visitors, and community navigators)—and its well-being. It can also become a key process for developing the capacities of the early childhood workforce to engage with families sensitively, without bias and with a supportive and healing relational stance (Balint, 1955; Frosch et al., 2018; Silver et al., 2025; Tobin et al., 2024). Training for reflective practice and supervision emphasizes a reflective stance for growing in self-knowledge, compassion, and relational skills (Huffhines et al., 2023; Silver et al., 2025).

Reflective practice in early childhood systems refers to the ongoing, intentional process by which professionals, organizations, and systems pause to critically examine their own actions, assumptions, and interactions in order to strengthen relationships, improve practice, and advance equity and effectiveness for children, families, and communities. Rooted in infant mental health and early childhood disciplines, reflective supervision offers structured, relationship-based support for professionals who work with families. It attends to the emotional and relational experience of the provider. In doing so, it promotes emotional regulation, which is an integral element of empathy (see Chapter 2), and allows providers to “witness the harm without being harmed.” The Facilitating Attuned Interactions

___________________

2 The relational health workforce includes an array of people whose primary responsibility is to foster relational health through building relationships of trust and coaching and modeling empathetic and nurturing relationships with children and families (Bruner, 2021).

training model, a promising best practice in pediatrics, targets parent–provider relationship-building (Taff et al., 2022). Simple Interactions is a similar model in early childcare and education settings that seeks to integrate a relationship-focused approach to coaching, monitoring, and evaluation activities.3 Incorporating reflective practice into team meetings, clinical supervision, and organizational culture can support sustainability and integrity to early relational health principles (Johnson et al., 2024; Schultz et al., 2018; Sparrow, 2016; Tomlin et al., 2016; Weatherston et al., 2009).

Research suggests that reflective supervision reduces burnout, enhances empathy, and strengthens relational attunement among frontline staff (Branch, 2010; Gilkerson, 2004). When implemented consistently, it creates parallel processes that mirror the kind of relationships providers can build with families—safe, curious, nonjudgmental, and growth promoting. Reflective supervision is especially critical in high-stress environments such as child welfare, substance use treatment, and perinatal mental health, where professionals are exposed to secondary trauma and complex relational dynamics.

Video feedback is well documented as a sustainable reflective practice strategy for supporting early relational health (Mendelsohn et al., 2018; Piccolo et al., 2024; Roby, Shaw, et al., 2021; Shaw et al., 2021). For example, the video feedback program used within the medical home, PlayReadVIP, has demonstrated significant improvements of social-emotional development, early learning, and early relational health. Other video feedback interventions (sometimes called Video Interaction Guidance, VIPP [Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting], or FIND [Filming Interactions to Nurture Development]) have been used in home visiting and other early childhood contexts. The evidence shows impacts on both maternal well-being and early relational health. As for maternal well-being, video-based self-reflection helps caregivers see their own strengths and moments of sensitivity with their child. This is associated with reduced maternal depression and stress, and improved sense of competence. And, by highlighting moments of sensitivity, attunement, and responsiveness, these interventions consistently impact early relational health by improving caregiver–child interactions, attachment security, and relational quality (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003; Fisher et al., 2016; Juffer et al., 2008; Kennedy et al., 2011).

___________________

3 See https://www.simpleinteractions.org/early-childhood.html.

4. Adopt Relational Abundance and Positive Family Assets Mindsets Using Relationally Focused, Healing-Centered Practices for Communities

Early childhood system-building that supports early relational health requires careful attention to the mindsets that influence leaders and their decision-making. A relational abundance mindset is a way of seeing and engaging with the world that emphasizes the richness, strength, and generative potential found in human relationships. Instead of focusing on scarcity (what families or communities lack), it highlights the assets, wisdom, and capacities that people bring to one another through connection. Within this frame cultural humility and fluency are essential for interpreting family interactions and require shifting from a deficit lens to an asset-based mindset that values and nurtures the strengths that all families possess (Waters & Anderson, 2025). What is more, the generational wisdom within communities and current principles within trauma-informed care (e.g., Two-Eyed Seeing, described earlier in this chapter) attest to the power of trusted relationships, welcomed narratives, and reflective practices; when combined, these create the context for healing and growth.

As described in previous chapters, early relational health manifests itself in culturally, community-, family-, and person-specific ways. Such variations inform understanding and meaning-making of parenting and supportive practices; they are deeply rooted within cultural values. Scholars have documented how, historically, many methods for assessing parent–child relationships have centered on Western norms and prioritized the outsider’s gaze over family voices (Walls et al., 2019; Wesner et al., 2024; Whitesell et al., 2018). Culture also influences how resilience is conceived, what managing stress and functioning well means, and how resilience is displayed; the nature and types of social connections sought; what and how knowledge is acquired and learning is supported; the expression of social and emotional competence; and the type of concrete support and care that is sought and provided. Within each of these domains, the observable practices of parenting, parent–child interactions, and early relational health take on various patterns of meaning, depending upon cultural context.

Without recognizing and understanding such variation and without an assets-based mindset, researchers, practitioners, and systems actors may default to deficit-based thinking and overlook the abundance and importance of children’s close relations with their range of family and neighbor adults and children across generations. For example, in research on infants’ and toddlers’ language learning, some studies limited their data collection to mother–child interactions, leading to interpretations of word gaps among certain populations (Fernald & Marchman, 2006; Hart & Risley, 1992; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015). However, when the broader language environment is considered—including speech among all who are present—the word gap disappears

or even reverses, with young children in working-class families hearing more speech than children in middle-class families (Sperry et al., 2019).

Practitioners must remain mindful of their own implicit biases and avoid imposing narrow interpretations on diverse parenting practices (Sul, 2019, 2021; Wesner et al., 2024). Families may distrust systems that have pathologized their ways of being. Frameworks such as Two-Eyed Seeing promote the integration of multiple worldviews by encouraging researchers and practitioners to see through one eye with the strengths of cultural knowledge and ways of knowing and through the other with the strengths of Western approaches, using both perspectives together in a balanced and respectful way for the benefit of all (Charlot-Swilley et al., 2024; Marshall, 2004; Rosado-May et al., 2020; Waters & Anderson, 2025). Through an assets-based mindset, practitioners value families as experts in their own relationships. Together, they can co-create meaning within each unique cultural context (Waters & Anderson, 2025).

5. Strengthen and Sustain Family Leadership Infrastructures in Communities

A growing body of evidence from family engagement efforts and place-based community initiatives highlights the important role of authentic family leadership in advancing early relational health. A growing consensus recognizes the need to move beyond family partnership, consultation, or engagement toward true family leadership with co-design, governance, and shared power (NASEM, 2024a). While family partnership implies collaboration, it often reflects a dynamic where professionals “invite” families to participate in a system already shaped without their voices. On the other hand, family leadership positions families not merely as participants but as essential drivers, decision-makers, visionaries, and co-creators whose lived experience and cultural wisdom are foundational to building systems that truly serve communities.

Principles of Family Leadership

In the context of early relational health, family leadership represents more than participation or engagement. It embodies the recognition that families and communities are the primary drivers of their own children’s relational health and the most knowledgeable experts about what their communities need to thrive. This pivot requires intentional investment in mentorship, eldership, and guidance to create a relational infrastructure that supports families as they step into leadership roles (Knowles et al., 2023).

The literature on community health workers4 reinforces that true leadership requires families to have actual decision-making power, not just advisory roles. Community health workers “share life experience with the people they serve and have firsthand knowledge of the causes and impacts of health inequity” (Knowles et al., 2023, p. 363), paralleling how families possess intimate knowledge of their child(ren)’s relational needs and community contexts that professionals cannot replicate through training alone. Knowles et al. (2023) warn that community health worker roles “may be in danger of becoming coopted” when health care systems focus on “their ability to convince patients to accept medical advice, reduce costly hospitalizations, or complete administrative tasks at a lower cost,” rather than honoring their unique expertise (p. 368). Similarly, family leadership can be diminished when systems view families primarily as implementers of professional agendas rather than as visionaries and decision-makers.

A 2024 National Academies report called on health care systems to provide education and training opportunities as well as compensation to family leaders; create pathways with local community programs to involve high school and college students from marginalized communities in early mentorship and job programs; and provide and encourage training and volunteer opportunities for health care system employees to partner with families and communities to co-design, build, implement, and evaluate programs (NASEM, 2024a, p. 399; see Recommendation 4-1). Additionally, it recognized the importance of compensating family leaders for their time and expertise and called on federal research agencies, state governments, and foundations to eliminate barriers that make it challenging for child-serving systems to financially compensate families for their participation in leadership efforts.

Systems can create workforce pathways for families to build knowledge, advocacy skills, and fluency in systems-change language without stripping away their authentic voices. This means creating space for families to drive vision, co-design solutions, and lead implementation of early relational health initiatives. See Box 4-2 for core family leadership principles based on the committee’s literature review.

Building on this foundation of authentic family leadership, the development of a robust early relational health workforce recognizes that

___________________

4 According to APHA (n.d.) a community health worker is “a frontline public health worker who is a trusted member of and/or has an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables the worker to serve as a liaison/link/intermediary between health/social services and the community to facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery. A community health worker also builds individual and community capacity by increasing health knowledge and self-sufficiency through a range of activities such as outreach, community education, informal counseling, social support and advocacy.”

BOX 4-2

Principles for Advancing Early Relational Health Through Family Leadership

These principles for family leadership can integrate efforts to dismantle existing barriers but also build meaningful, culturally congruent supports for families and community well-being.

- Families are primary experts about their children and their families. Families are recognized as proximal experts who understand their children and their own needs best. Their knowledge, rooted in daily lived experiences and the wisdom of cultural traditions, is essential to promoting early relational health (Fu et al., 2024; Lansford, 2022).

- Trust-building advances through relational engagement with families. Families and providers build shared trust through open communication and empathic and compassionate interactions. Relational trust is a key driver of effective practice for all families, especially when built over time and grounded in mutual respect (Bryk & Schneider, 2002).

- Shared power is practiced and sustained with families. Families actively participate in planning and decision-making processes across new and existing programs and are co-creators in policy advocacy work that focuses on efforts for their benefit. Just as all intervention experts benefit from coaching, training, and guidance, so too can family leaders.

- Cultural responsiveness and community rootedness reveal multiple ways of understanding and observing early relational health. Family leadership in early relational health recognizes that healthy relationships are expressed differently across cultural contexts and creates space for multiple ways of knowing.

- Family strength and asset-based orientation permeates the ecosystem. The approach centers family strengths, cultural protective factors, and long-standing community wisdom rather than deficits or risk factors (García Coll et al., 1996; McKnight & Kretzmann, 1993; South et al., 2024). This shift affirms families as resourceful, fostering dignity and trust while shaping interventions that build on what is already working within communities.

families contribute their expertise through diverse pathways such as peer support and grassroots advocacy; some choose to transition into professional roles. While professionalization represents one valuable option, it needs to expand rather than replace community-led approaches where families drive change through their cultural wisdom and lived experience. For families who seek professional pathways, systems can create opportunities that

respect community connections and affirm cultural knowledge, bridging lived experience with professional development that offers sustainable wages and honors their expertise. The goal is not to assimilate family leadership into institutional frameworks but to ensure that families have genuine choices about how to contribute their knowledge to early relational health systems, whether through community organizing, peer networks, or professional roles that they help to define.

Family members who have navigated early childhood, mental health, or public systems bring a unique and essential perspective to this work. Training, mentorship, and leadership development need to be shaped alongside the communities they intend to serve rather than imposed by external institutions. Too often, support structures are designed from dominant institutional perspectives that fail to reflect the lived realities and cultural contexts of the families involved. When development opportunities are created without community authorship, they risk replicating power imbalances and devaluing the knowledge already held by families and communities.

Workforce Training Infrastructure

Across the early childhood ecosystem, public systems and philanthropic intermediaries have launched training and mentorship programs aimed at integrating families into system-building. These efforts often seek to build capacity by pairing lived experience with professional development. While these approaches can be impactful, they raise critical questions when training is externally defined, selected, and delivered without deep partnership or cultural alignment. In these cases, the process can feel extractive to families, reinforcing traditional power hierarchies despite inclusion efforts. The power dynamic embedded in many training models can be subtle but consequential when professionals or system leaders determine what skills families need, how leadership is defined, and what readiness looks like. This reflects a mental model where families are positioned as recipients of expertise rather than holders of it. Such approaches risk unintentionally replicating the very inequities they aim to dismantle.

Authentic integration of lived experience into early relational health systems requires that families and community-based organizations co-define both the content and purpose of training and support that is needed. In community-rooted models, leadership emerges from the affirmation of shared cultural wisdom and relational experience, not from compliance with external criteria. Leadership that leads to equity is grounded in community wisdom (Carey Sims, 2021). These models are not only culturally congruent but also more sustainable because they build on existing networks of trust, care, and collective knowledge. Trust is essential for creating healthy,

reciprocal relationships and safe environments; engaging in transparent interactions; successfully negotiating power differentials; and supporting equity (Lansing et al., 2023).

Research demonstrates that leadership programs can affirm, center, and strengthen the collective skills, knowledge, and aspirations of communities to advance early relational health for all families (Carey Sims, 2021). However, community-driven, collective leadership is challenging to measure or understand using surveys or quantitative research methodologies. The knowledge in which such leadership is rooted is borne out of generations of living, encoded in ceremonies and shared meals, analyzed in spaces such as barbershops, and disseminated through webs of relationships (Carey Sims, 2021).

Culturally Responsive and Equitable Evaluation

To meaningfully assess and honor this kind of knowledge, methodologies such as Culturally Responsive and Equitable Evaluation (CREE) offer critical alternatives. CREE approaches foreground values, voices, and definitions of success held by communities themselves. Rather than imposing external measures, CREE seeks to co-create meaning and impact through processes that are relational, reflective, and rooted in cultural context (Adedoyin et al., 2024). This presents a critical opportunity for transformation, one in which early relational health systems can pivot toward approaches that elevate family leadership and community wisdom as essential to improving care.

Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Family Leadership Certificate Program

When family leaders combine their lived experiences with specialized training in infant and early childhood mental health, it creates a transformative foundation for a more responsive early relational health ecosystem that meets the needs of all families. One promising example of this shift is the Georgetown Thrive Center Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Family Leadership Certificate Program,5 which offers a comprehensive approach to supporting family leaders. The program honors the expertise that families bring and builds on their strengths by supporting the development of additional tools and strategies for navigating and transforming systems. Co-created with family and community leaders, the program centers lived expertise and emphasizes collaborative curriculum development rooted in community realities. This 9-month training program, which does not require a higher education degree for entry, teaches core competencies for community health workers, with knowledge specialization in infant, early childhood, and family mental health.

___________________

5 See https://scs.georgetown.edu/programs/519/certificate-in-infant-early-childhood-mental-health-family-leadership/.

Recognizing the vital role families play in the mental health ecosystem, the term community mental health workers was coined to reflect the unique role that blends lived experience with training in mental health support. When placed in early childhood settings, family leaders often serve as vital bridges between teachers, the certificate program, and families, helping to support culturally responsive communication and strengthen trust-building. This revitalizing approach reimagines the role of families as paraprofessionals and change agents within the early childhood ecosystem.

In addition to academic instruction, the program provides wraparound support services to families enrolled, acknowledging the importance of addressing real-life challenges while participants are building on their existing leadership and workforce capacity skills. This includes access to concrete resources, individualized academic support, and opportunities for reflection. This transforms not only systems but also conditions of families’ everyday lives. As one family leader stated in a public session of the committee,

When my money got better […] opportunities for economic mobility, my mental health got better. [It was] a moment to breathe. The relational health of my young family got better. [I had] space to focus on my children and family’s strengths. And now that my bills no longer came in pastel-colored envelopes, I felt a confidence that I had finally reached a place that I had grown tremendously.

This testimony captures what becomes possible when systems recognize and invest in the leadership and lived experience of families, not just as beneficiaries of services but as essential voices and drivers of community transformation.

PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES FOR ADVANCING EARLY RELATIONAL HEALTH

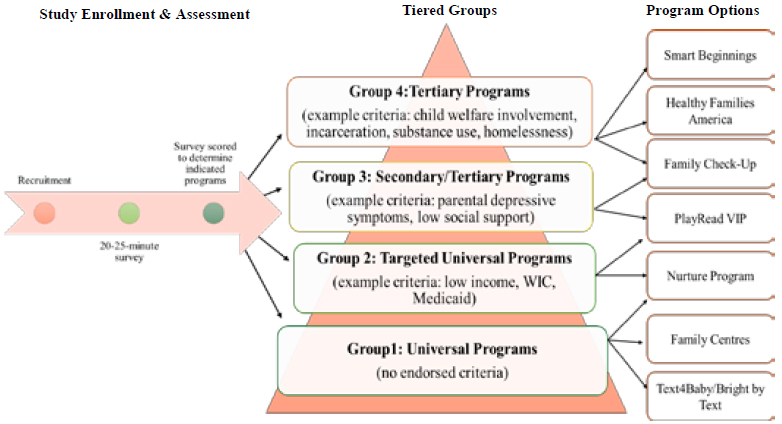

The practices and principles described in this chapter can inform systems change, programs, and initiatives that aim to promote early relational health within a tiered and integrated public health approach. Such efforts include societal, universal supports to promote healthy relationships (e.g., public awareness campaigns); preventive and targeted interventions (e.g., a continuum of a relational health workforce and home visiting services); and indicated treatments that repair strained relationships (e.g., Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up, CPP, Let’s Connect, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy; Level 3 in Figure 4-1).

Gathered from the committee’s review and expert testimony, the

following sections share examples of existing approaches and programs aligned with a tiered public health framework that support early relational health across ecological levels of influence (individual and family, community, and system). The public health framework emphasizes that population-level approaches to early relational health need to go beyond identifying individual risks and instead focus on designing communities and systems that make strong relationships easier to form and maintain.

The programs described in this section have features common to those designed to enhance early relational health by strengthening the foundational relationships that support child development. Despite differences in scope and implementation, they share several overlapping components, including building trusted relationships and fostering social connectedness (which encompasses cultural context), supporting children’s social-emotional competence, addressing social determinants of health and family risk factors (through assessment and referrals), and providing parents with knowledge and skills to nurture their children’s development. Taken together, these initiatives illustrate a continuum of strategies that collectively promote child and family well-being across multiple levels of influence.

Individual- and Family-Level Efforts

The sections below describe examples of models and programs that can support early relational health at the individual and family levels, across child-serving sectors. These models and programs represent the continuum of the tiered public health framework, ranging from universal promotion efforts to preventive and targeted interventions and indicated treatments.

Pediatric Primary Care

Pediatric primary care has near-universal reach to young children and their caregivers. Over 90% of U.S. children receive at least one well-child visit in the first year of life (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022). This makes pediatric settings an opportune platform for early relational health promotion. Relationship-centered models—such as HealthySteps, DULCE (Developmental Understanding and Legal Collaboration for Everyone), Reach Out and Read, and PlayReadVIP (Mendelsohn et al., 2018)—embed developmental and relational support directly into primary care visits. These models can improve caregiver–child engagement, increase referrals to community resources, and reduce family stress (Guyer et al., 2003; Zuckerman et al., 2013). The sections below describe some pediatric primary care models shared with the committee that can be used to support early relational health.

HealthySteps

HealthySteps is an interdisciplinary program embedded

within pediatric primary care that promotes positive parenting, health, and development among children from birth through age 3 years (sometimes extending to age 5 years; Guyer et al., 2003). A HealthySteps specialist works with families as part of the primary care team, attending well-child visits and providing guidance on early relational health that is in alignment with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Bright Futures Guidelines (Roby, Shaw, et al., 2021; Valado et al., 2019). The HealthySteps (n.d.) service model is organized into three tiers of service, with eight core components to ensure that all families receive supports that are aligned with their needs (Valado et al., 2019).6 Extensive evidence of positive effects includes fewer mental health symptoms (although higher stress), increases in sensitive caregiving and reductions in harsh parenting practices, and fewer child behavior problems (Piotrowski et al., 2009; Valado et al., 2019). HealthySteps parents were also more likely to attend well-child and vaccination visits and reported greater satisfaction with the quality of their overall care (Valado et al., 2019).

Safe Environment for Every Kid

The Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) program leverages routine well-child visits to identify family stressors systematically (via completion of a short parent questionnaire, which covers items related to social drivers of health and family functioning), provide immediate support through parental handouts, and connect households to community resources through referrals (Dubowitz, 2014). It has demonstrated efficacy in reducing risk factors for child maltreatment and enhancing early relational health by supporting both parents and providers in addressing social determinants within the primary care setting. A randomized controlled trial involving over 500 families in a low-income pediatric clinic demonstrated that SEEK reduced child maltreatment indicators, including fewer reports to child protective services, delayed immunizations, and incidents of harsh discipline (Dubowitz et al., 2009). As noted in the SEEK evaluation studies, as well as in the recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force report on primary care interventions to prevent child maltreatment, child protective services findings should be interpreted with caution

___________________

6 Tier 1 is universal services with the first three core components: (a) child developmental, social-emotional, and behavioral screening; (b) screening for family needs (e.g., parental depression, other risk factors, and social determinants of health); and (c) a family support line (e.g., phone, text, email, app, online portal). Tier 2 is short-term supports or specific time-limited concerns. It includes all tier 1 serves plus core components 4–7: (d) child development and behavior consults (1–3 visits), (e) care coordination and systems navigation, (f) positive parenting guidance and information (varied topics and formats), and (g) early learning resources (strategies and activities across developmental ages). Tier 3 includes comprehensive services (for families most at risk). It includes all tier 1 and 2 services plus core component 8: ongoing, preventive team-based well-child visits (start as early as possible, specialist integrated into visits; HealthySteps, n.d.).

given the inherent challenges of measuring child maltreatment through substantiated reports and related outcomes (Dubowitz et al., 2012; Viswanathan et al., 2024).

DULCE

Developmental Understanding and Legal Collaboration for Everyone is a universal, evidence-based pediatric care approach that addresses social determinants of health and supports early relational health for infants from birth to age 6 months (Sege et al., 2014). The model embeds a family specialist within routine well-child visits to build trusting relationships; assess family needs; and connect families to community resources such as housing, food, legal aid, and mental health services (Arbour et al., 2022). The family specialist works closely with an interdisciplinary team, including an early childhood system representative, legal partner, and pediatric and behavioral health clinicians. This cross-sector team holds regular case reviews to ensure coordinated support. Including a legal partner helps families resolve common legal challenges that can threaten family stability. Evidence shows that DULCE increases routine health care visits, reduces emergency room visits (Sege et al., 2015), increases parental sense of agency and resilience, and decreases levels of self-reported stress (Monahan et al., 2024).

Reach Out and Read

Reach Out and Read, another model implemented in the health care system, provides children’s books, anticipatory guidance, and modeling at pediatric well-child visits for families with children from birth to age 5 years. Evaluations of the program have found increased shared reading and child vocabulary (Garbe et al., 2023; High et al., 2000; Mendelsohn et al., 2001; Needlman et al., 1991, 2005). Reach out and Read has been implemented in more than 6,500 health care sites, reaching more than 4.5 million children each year.

Additional Models

3-2-1 IMPACT (Integrated Model for Parents and Children Together) offers one example of an integrated pediatric primary care model. It is an initiative of New York City Health + Hospitals, which layers Reach Out and Read, PlayReadVIP, and HealthySteps in pediatric primary care. It links prenatal and mental health services and includes substantial delivery by community health workers (McCord et al., 2024).

Two additional recent innovations illustrate how pediatric care can serve not only as a clinical platform for early relational health but also as a bridge to community-based systems of support (Shaw et al., 2024). Mendelsohn et al. (2025), building on insights from the public health framework, told the committee that these models offer a “layering of services with varying strategies and intensity that are delivered across multiple sectors.” Smart Beginnings (Roby, Miller, et al., 2021; Shaw et al., 2021) and the Pittsburgh Study (Krug et al., 2025) offer complementary models. Smart Beginnings embeds tiered early relational health interventions directly into pediatric well-child visits (see Box 4-3), while the Pittsburgh Study extends

BOX 4-3

Smart Beginnings

Smart Beginnings is an integrated, tiered prevention model embedded in pediatric primary care. It combines PlayReadVIP (Mendelsohn et al., 2018), a universal clinic-based coaching program to strengthen positive, responsive parenting, with the Family Check-Up (Shaw et al., 2006), a targeted family-centered, home-based intervention that utilizes an ecologically focused assessment to motivate parents to address challenges with child-rearing behaviors and includes follow-up sessions on parenting (Everyday Parenting) and factors that compromise parenting quality for families facing additional risk factors. In Smart Beginnings, PlayReadVIP is a primary prevention program offered to low-income families beginning early with multiple visits (13–15 recommended sessions from birth to child age 5 years). More intensive services are offered (home-based secondary/tertiary prevention) through the Family Check-Up. This integration of two approaches provides opportunities for identifying, engaging, and intervening with families (Shaw et al., 2021). Evidence demonstrated improved parental support of infant cognitive stimulation (Miller, Roby, et al., 2023; Roby, Miller, et al., 2021), which in turn was associated with increased child language and literacy skills at age 2 years (Miller et al., 2024). Smart Beginnings also has demonstrated effects on greater service referrals to early intervention or early childhood special education programs (Hunter et al., 2025).

City’s First Readers in New York City uses this model and is focused on shared reading among families, childcare providers, and early childhood educators as a positive practice aligned with early relational health. The initiative links programs across 17 platforms and settings, including at the community level through Literacy in Community, the city’s public library systems, the health care system, childcare providers, home visiting, and early child education, among others. Canfield et al. (2020) showed increased impacts on shared reading resulting from participation in both Reach Out and Read and library programs (Canfield et al., 2020).

a similar framework across community settings to reach families at a population level (see Box 4-4).

Home Visiting

Grounded in developmental, attachment, and ecological frameworks, home visiting programs are evidence-based preventive models that aim to strengthen early relational health by enhancing parenting capacity and

BOX 4-4

The Pittsburgh Study’s Early Childhood Collaborative

The Pittsburgh Study (TPS) is a community-partnered, population-level initiative that applies a tiered public health model to promote early relational health among families of children under age 5 years. TPS is strongly aligned with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations for multitiered population-based approaches to early relational health. An important component of TPS’s Early Childhood Collaborative is strong partnerships with health care and community agencies serving families of young children and a community collaborative of residents within communities to advise on recruitment and study methods. Families are recruited through several early childcare settings, including birthing hospitals (screened after delivery), pediatric care system, and WIC locations.a Consenting parents completed a survey assessing family strengths, adversity, and risk of toxic stress—specifically sociodemographic risks, child health risk and well-being, supportive/proactive parenting and parental well-being, social support, and involvement with the child welfare or justice systems. These assessments are scored in real time using standardized cut-offs and assign parents to one of four groups characterized by type of parenting support programs offered (see Figure 4-2-1), ranging from universal text message programs to intensive home visiting, all of which are offered or delivered within trusted settings such as pediatric clinics, WIC offices, libraries, and early learning centers. Early results indicate strong feasibility and high engagement (Krug et al., 2025).

Together Growing Strong uses this model in Sunset Park, New York, utilizing community and stakeholder participation to link health care, education, and community-level systems in providing multiple levels of service related to early relational health and family well-being (Krug et al., 2025).

SOURCE: Krug et al., 2025.

______________

a WIC stands for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

supporting sensitive, responsive caregiving (Britto et al., 2017). Programs vary in terms of their theory-of-change models, goals, content, timing, and population served (Sweet & Appelbaum, 2004), as well as who delivers them (paraprofessional or professional) and how they are delivered (e.g., flexibly determined or tailored, manualized or not manualized; Filene et al., 2013). Many of the most widely adopted models are complex, addressing diverse outcomes through repeated visits over extended durations, typically 2 years or longer (Duggan et al., 2018). Most programs aim to enhance family health, promote positive parenting and child development, and prevent child maltreatment (Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2024). In partnership with families, home visitors usually assess strengths, needs, concerns, and interests through education support during home visits and connecting families with appropriate services as needed. Despite the heterogeneity across programs, previous reviews (Alves et al., 2024; Avellar & Supplee, 2013; Sama-Miller et al., 2024) and meta-analyses (Kendrick et al., 2000; Nievar et al., 2010; Supplee & Duggan, 2019; Sweet & Appelbaum, 2004) have demonstrated effectiveness of home visiting programs for numerous family and child outcomes.

Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) regularly conducts systematic reviews of the existing literature to assess which home visiting models have sufficient evidence to meet at least one of the two U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ([HHS] Office of the Surgeon General (2024) criteria for being considered “an evidence-based early childhood home visiting service delivery model” (p. 1). The two HHS criteria are (a) at least one high- or moderate-quality impact study of the model finds favorable, statistically significant impacts in two or more of the eight outcome domains, and/or (b) at least two high- or moderate-quality impact studies of the model using nonoverlapping analytic study samples find one or more favorable, statistically significant impact in the same domain (HHS Office of the Surgeon General, 2024). The eight domains include maternal health; child health; positive parenting practices; child development and school readiness; reductions in child maltreatment; family economic self-sufficiency; linkages and referrals to community resources and supports; and reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime. In the most recent HomVEE review (released November 2024), of the 72 home visiting models assessed, 27 met HHS criteria and 25 met both HHS criteria and requirements for MIECHV implementation (see Table 4-2).

One of the eligibility requirements to receive MIECHV funding is that a model must meet the HHS criteria for evidence of effectiveness as determined by HomVEE (National Home Visiting Coalition, n.d.). Established in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act to implement evidence-based home visiting for pregnant women and children up to age 5

TABLE 4-2 Models Meeting HHS and MIECHV Criteria for Funding

| Model | Review Last Updated |

|---|---|

| Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up (ABC) Infant | 2020 |

| Child First | 2024 |

| Early Head Start Home-Based Option (EHS-HBO) | 2024 |

| Early Intervention Program for Adolescent Mothers | 2011 |

| Early Start (New Zealand) | 2023 |

| Family Check-Up® For Children | 2021 |

| Family Connects | 2023 |

| Family Spirit® | 2022 |

| Health Access Nurturing Development Services (HANDS) Program | 2024 |

| Healthy Beginnings | 2024 |

| Healthy Families America® (HFA) | 2024 |

| HealthySteps (National Evaluation 1996 Protocol)a | 2011 |

| Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters® (HIPPY) | 2023 |

| Intervention Nurses Start Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories | 2022 |

| Maternal Early Childhood Sustained Home Visiting Program | 2023 |

| Maternal Infant Health Outreach Worker® (MIHOW) | 2022 |

| Maternal Infant Health Program (MIHP) | 2024 |

| Nurse-Family Partnership® (NFP) | 2024 |

| Parents as Teachers® (PAT) | 2019 |

| Play and Learning Strategies (PALS) Infant | 2019 |

| Preparing for Life—Home Visiting | 2023 |

| Promoting First Relationships®—Home Visiting Intervention Model | 2021 |

| SafeCare® Augmented | 2018 |

| Video-Feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting—Sensitive Discipline (VIPP-SD) | 2023 |

| Video-Feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting (VIPP) | 2023 |

a These results focus on HealthySteps as implemented in the 1996 evaluation. HHS has determined that home visiting is not the primary service delivery strategy, and the model does not meet current requirements for MIECHV program implementation.

NOTE: HHS = U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; MIECHV = Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting.

SOURCE: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation (OPRE), 2024.

BOX 4-5

Nurse Home Visiting Programs

Nurse Family Partnership

The Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) is an intensive, strengths-based, trauma- and violence-informed community health program designed to improve outcomes for first-time mothers and their children living in poverty. NFP aims to enhance maternal and child well-being through regular home visits conducted by specially trained registered nurses. Services begin early in pregnancy, no later than the 28th week of gestation, and continue until the child’s second birthday, with visit frequency tailored to the family’s level of need and the child’s developmental stage.

The program targets three key domains: improving pregnancy outcomes by supporting maternal health during pregnancy; promoting sensitive, competent caregiving to support child health and development; and enhancing parental life trajectories by helping participants pursue education, employment, and future family planning. NFP nurses aim to form trusted, enduring relationships with the families they serve, offering guidance on topics ranging from infant care and health to long-term stability and goal-setting (California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse, 2025; National Home Visiting Resource Center, 2025).

Family Connects

Family Connects is a universal, community-based nurse home visiting program designed to improve population-level outcomes in infancy and early childhood by offering timely, integrated support to all families following the birth of a child. Grounded in a whole-person, whole-family approach to health, the model seeks to engage families at a moment of life-changing transition by assessing newborn and maternal well-being, identifying needs and strengths, and connecting families to community-based services tailored to their preferences and circumstances.

Family Connects nurses are trained to conduct comprehensive assessments of the mother and infant; address immediate concerns, including medical issues requiring urgent care; and collaboratively identify actionable next steps. Nurses consider the needs of the entire family system, including mental health and medical support for other caregivers, and they follow up to ensure families are successfully connected to appropriate services. Each family in an affiliated community is offered a home visit free of charge, typically lasting up to 2 hours and occurring within the first 3 weeks postpartum. While most families receive one visit, up to three visits may be provided as needed. The model aims to reach at least 60% of families with newborns in each participating community (National Home Visiting Resource Center, 2025).

years living in at-risk communities, the MIECHV was reauthorized in 2022 for an additional 5 years. In fiscal year 2024, the MIECHV program served all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and five U.S. territories, serving over 150,000 parents and children and providing approximately 990,000 home visits (Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2024). To illustrate the range of prevention strategies supported through MIECHV, Box 4-5 highlights two nurse home visiting programs that meet HomVEE evidence standards. The Nurse-Family Partnership® (NFP) is a preventive intervention serving first-time parents with low incomes (Olds, 2006; Olds & Yost, 2020), while Family Connects adopts a universal approach (Dodge et al., 2014; Goodman et al., 2021).