Is monkeypox spreading through the air like COVID-19?

Based on Science

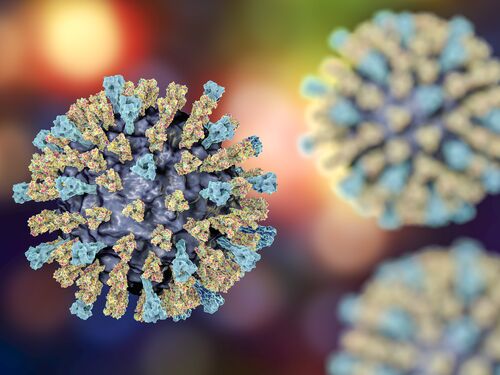

Monkeypox is not spread through the air. Unlike the virus that causes COVID-19, monkeypox, renamed mpox, is primarily spread through close contact, either from an animal to a person or from person to person.

Last update October 25, 2022

What is mpox?

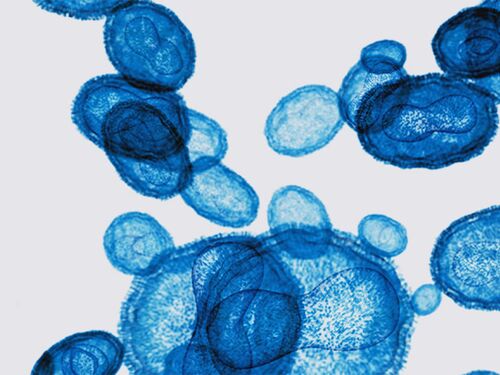

Mpox is caused by an orthopoxvirus, not a coronavirus like SARS-CoV-2. It is related to variola, the virus that causes smallpox. Common mpox symptoms include fever, swollen lymph nodes, and headaches, although these symptoms may not always occur. Usually, a rash also develops. In the 2022 outbreak, the rash most commonly occurred in the oral, anal, or genital area.

Symptoms usually develop within 3 weeks of exposure to the virus. It takes 2–4 weeks to recover from the illness.

Mpox is spread most commonly through close contact.

Mpox is what is known as a zoonotic disease, which means it infects some animals as well as humans. Prior to the 2022 outbreak, most cases involved a person coming into contact with an infected animal, either in the west and central African countries in which the disease is endemic (meaning the disease was consistently present in the region prior to the 2022 outbreak) or through animals imported from that region. In 2003, the United States experienced a mpox outbreak connected to the importation of rodents from Ghana into Texas.

Mpox spreads from person to person through direct contact, including contact with the rash, scabs, or body fluids from someone infected with mpox. People with mpox can have virus in their saliva and breathe out virus. But unlike the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, the mpox virus does not spread easily long distances through the air. Transmission through respiratory secretions appears to occur through kissing and in other situations with prolonged face-to-face contact.

Mpox does not spread as easily as SARS-CoV-2.

Because mpox does not spread readily through the air and is endemic in only one part of the world, most people are at low risk of catching the disease. The 2022 outbreak spread primarily through intimate contact. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends that people who have had close contact with someone with mpox get vaccinated with a vaccine originally licensed for smallpox and now available for prevention of both smallpox and mpox. It also recommends vaccination for:

Gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men, people who are transgender, and people who are nonbinary or gender-diverse and who, in the last 6 months, have had sex with multiple partners, had sex at a commercial sex venue, or had sex at an event where mpox transmission is occurring.

Gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men, people who are transgender, and people who are nonbinary or gender-diverse who have had a new diagnosis of one or more sexually transmitted diseases.

People who work in settings where there is a risk of being exposed to mpox, such as in a laboratory with orthopoxviruses or as part of a health care response team.

While most of the world’s population may be at low risk, the disease has been a public health concern for decades in countries where it is endemic. Vaccination campaigns to prevent smallpox ceased in the late 1970s, and smallpox was declared eradicated from the world in 1980. Since that time, cases of mpox have increased in west and central Africa. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where most cases prior to the 2022 outbreak were reported, the average incidence of disease increased 20 times from 1981–1986 to 2006–2007. Most cases in both periods of time were children under the age of 15, and nearly all cases occurred in people who had not been vaccinated against smallpox. In August 2024, the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency of international concern after more than 15,000 cases and 500 deaths were reported in the DRC so far that year. In the summer of 2024, mpox cases were reported in many neighboring countries, including four that had not previously reported cases. Making vaccines and drug therapies for mpox available in west and central Africa―and greater support for health infrastructure and public health resources (including disease surveillance and response capabilities) in this region, particularly in rural areas―would reduce suffering in places where the disease is endemic. It would also lower the risk of mpox outbreaks and of the virus becoming endemic in more parts of the world.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

More like this

Discover

Events

Right Now & Next Up

Stay in the loop with can’t-miss sessions, live events, and activities happening over the next two days.

NAS Building Guided Tours Available!

Participate in a one-hour guided tour of the historic National Academy of Sciences building, highlighting its distinctive architecture, renowned artwork, and the intersection of art, science, and culture.