Preparing for Future Pandemics: Using lessons from the current crisis to improve future responses

Feature Story

By Sara Frueh

Last update October 14, 2020

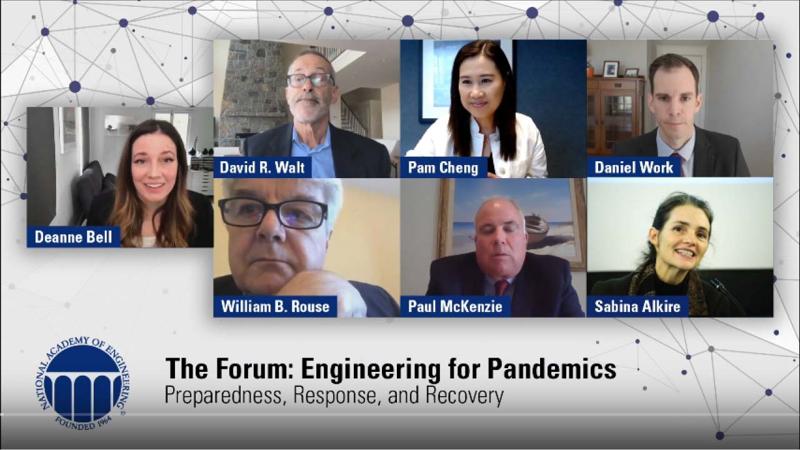

As many nations around the world have struggled with high rates of infections and deaths from COVID-19, Taiwan has kept the number of deaths from the disease to less than 10 — by drawing upon its previous experience with SARS, said chemical engineer Pam Cheng, speaking at last week’s annual meeting of the National Academy of Engineering.

Similarly, the rest of the world can use its experience with SARS-CoV-2 to lessen the toll of future disease outbreaks. “[An] element that can be very effective in prevention is the notion of lessons learned — growing a memory,” said Cheng. “We must learn from this, we must grow [our] memory, and we’ve got to be prepared.”

Cheng, who is executive vice president for global operations and information technology at AstraZeneca, was one of multiple speakers at NAE’s annual meeting who reflected on what can be learned from the pandemic.

The topic was the focus of a presentation by David Walt, an NAE member and professor of bioinspired engineering at Harvard Medical School. He explained how the pandemic revealed weaknesses in the global supply chain, which became less global during the pandemic. “When countries need materials and supplies for their own use, domestic needs take precedence,” he said.

For example, the U.S. had challenges acquiring simple items such as nasal swabs because of its reliance on Asian suppliers, and faced shortages in disinfecting and alcohol wipes because of its reliance on global chemical suppliers. “Such critical supplies should be stocked well in advance of the need, or domestic supplies need to be available,” said Walt.

Our experience with COVID-19 testing has also yielded lessons, such as the need for federal coordination, he said. “Leaving testing to states is not the right approach. States were vying for tests, and those willing to pay more got them.” Testing supplies are finite, and they should be deployed where they are needed rather than based on who can pay, he said, to ensure that disadvantaged communities have access to them.

Researchers embraced the expertise of clinicians to help identify problems they were facing in the clinic, and they partnered with engineers to help find scalable solutions.

Walt noted a positive take-away from the pandemic: the benefits of deep collaborations among clinicians, engineers, and research scientists, which enabled a rapid response. “Barriers in academic medicine and in industry were completely broken,” he said. “For example, researchers embraced the expertise of clinicians to help identify problems they were facing in the clinic, and they partnered with engineers to help find scalable solutions.”

Other types of collaboration — across multiple industries, and between industry and government agencies — have emerged and played important roles in the pandemic response, observed Paul Mackenzie, chief operating officer of CSL Limited, during a later panel discussion. “That’s something we probably need to improve for future pandemics that will come.” He also explained the critical role advanced manufacturing methods have played in the COVID-19 response — for example, by enabling the rapid scale-up of therapeutics and vaccines — and stressed the importance of investing in these approaches before pandemics happen.

Responses to pandemics can also lead to benefits that extend more broadly, said Sabina Alkire, director of the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. For example, the Ebola epidemic prompted work on wider aspects of poverty, because addressing the epidemic required working on health systems, delivering nutritional supplies to schools, and mobilizing communities. These efforts have had a lasting, positive impact, said Alkire. Sierra Leone actually reduced poverty during the Ebola epidemic. “It’s not preventing pandemics, but it’s also using them to look at broader issues.”

Watch sessions from the 56th NAE Annual Meeting, Oct. 4-7, 2020

More like this

Events

Right Now & Next Up

Stay in the loop with can’t-miss sessions, live events, and activities happening over the next two days.

TRB Annual Meeting | January 11 - 15, 2026

January 11 - 15, 2026 | The TRB Annual Meeting brings together thousands of transportation professionals worldwide for sessions across all modes and sectors.