The Secret Life of Numbers: 50 Easy Pieces on How Mathematicians Work and Think (2006)

Chapter: 4 Daniel Bernoulli and His Difficult Family

4

Daniel Bernoulli and His Difficult Family

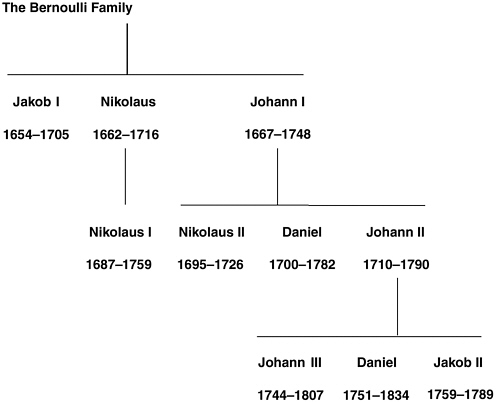

More than two centuries have passed since the death of one of the most distinguished mathematicians in history: Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782). The name Bernoulli calls for precision since the family from the Swiss town of Basle produced no fewer than eight outstanding mathematicians within three generations. Because the same given names kept being used by the family over and over again, a numbering system was adopted to tell fathers, brothers, sons, and cousins apart. It starts with Jakob I and his brother Johann I (the third brother, Nikolaus, being an artist, wasn’t given a number). Then there are, in the next generation, Nikolaus I and Johann’s three sons—Nikolaus II, Daniel, and Johann II. Finally, the two sons of Johann II, called Johann III and Jakob II, followed in the footsteps of their brilliant ancestors. (Johann’s third son, Daniel, didn’t get any further than being deputy professor at the University of Basle. Hence he wasn’t given a number, which is why his famous uncle and namesake didn’t need one either.)

Together with Isaac Newton, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Leonhard Euler, and Joseph-Louis Lagrange, the Bernoulli family dominated mathematics and physics in the 17th and 18th centuries. The family members were interested in differential calculus, geometry, mechanics, ballistics, thermodynamics, hydrodynamics, optics, elasticity, magnetism, astronomy, and probability theory. For more than 30 years, the Swiss National Fund has been supporting work on an edition of the complete works of Jakob I, Johann I, and Daniel. The complete edition will comprise 24 volumes. Another 15 volumes, including a selection of their 8,000 letters, is to follow.

Unfortunately, the gentlemen from Basle were as con-

ceited and arrogant as they were brilliant and engaged constantly in rivalry, jealousy, and public rows. Actually, everything had started so idyllically. Jakob I, who had acquired his knowledge in the natural sciences as an autodidact and went on to teach experimental physics at the University of Basle, secretly introduced his younger brother to the mysteries of mathematics. This was very much against the will of their parents, who wanted the younger brother to embark on a career in commerce after the elder son had already refused to embark on the clerical career they had planned for him.

But the harmony between the two highly gifted brothers soon turned into a bitter argument. The conflict began when Jakob I, annoyed by Johann’s bragging, claimed in public that the works of his former student were but copies of his own results. Next Jakob I—who by then held the chair of mathematics at the University of Basle—plotted successfully against his brother’s appointment to his department. So Johann I had to teach at the University of Groningen before finally being offered a chair in Basle for … Ancient Greek. But fate decided otherwise, and just when Johann set off for his native town, the news reached him that Jakob had died. Thus the not-too-grief-stricken brother was given the chair of mathematics in Basle after all. Jakob’s most important opus, his Ars Conjectandi (The Art of Conjecture), which appeared after his death, formed the basis of probability theory.

But don’t believe that Johann I learned anything from this sad story. In educating his own sons he committed exactly the same mistakes as his father had done before him. Claiming that mathematics couldn’t provide a living, Johann tried to bully the most gifted of his three sons, Daniel, into a career in commerce. When this attempt proved unsuccessful, he allowed him to study medicine—all this in order to prevent his son from becoming a competitor. But the sons followed the example of their elders, and Daniel, while studying medicine, took lessons in mathematics from his older brother, Nikolaus II. In 1720 he traveled to Venice to work as a physician. However, his heart belonged to physics and mathematics, and

during his stay he acquired such a great reputation in these fields that Peter the Great offered him a chair at the Academy of Science in St. Petersburg.

In 1725 Daniel traveled to the capital of the Russian empire, together with his brother Nikolaus II, who had also been offered a professorship for mathematics at the academy. Their joint sojourn didn’t last long. Hardly eight months after their arrival Nikolaus II fell ill with a fever and died. Daniel, who possessed more of a sense of family than his father, was very distressed and wanted to return to Basle. But Johann I didn’t want to have his son back home. Instead, he sent one of his pupils to St. Petersburg to keep Daniel company. This was an extremely lucky coincidence, since the pupil was none other than Leonhard Euler, the only contemporary who could compete with the Bernoullis when it came to mathematical talent. A close friendship developed between the two Swiss

mathematicians in exile. The six years they spent together in St. Petersburg were the most productive time of Daniel’s life.

After he returned to Basle, the quarrels within the family started anew. When Daniel won the prize of the Parisian Academy of Science jointly with his father for a paper on astronomy, Johann I didn’t exactly act like a proud father. On the contrary, he kicked his son out of the house. Daniel was to win the great prize of the academy nine times altogether. But worse was yet to come: In 1738 Daniel published his magnum opus, Hydrodynamica. Johann I read the book, hurriedly wrote one of his own with the title Hydraulica, dated it back to 1732, and claimed to be the inventor of fluid dynamics. The plagiarism was soon uncovered, and Johann was ridiculed by his colleagues. But his son never recovered from the blow.