Spread, Scale, and Sustainability in Population Health: Workshop Summary (2015)

Chapter: Appendix C: Background Questions and Panelist Responses

Appendix C

Background Questions and Panelist Responses

Panelists were asked to provide the roundtable with written responses to the following questions prior to the workshop. The responses provided by the panelists for each case example follow.

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

- Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

- How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

- How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up effort?

- How do you measure this?

- What proportion of your target population have you reached?

- How do you measure this?

- What is your ultimate goal?

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

- How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

- Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your ideas, practices, programs, policies.

-

- What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

- What steps did you go through in order to spread a program?

- What investment strategies did you use to spread a program?

- Did you need to make organizational changes to bring something to scale?

- Were resources already in place to support the scaling strategy, or did you need to find special resources to implement the scaling?

- If you needed to find additional resources, how did you do it?

- What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

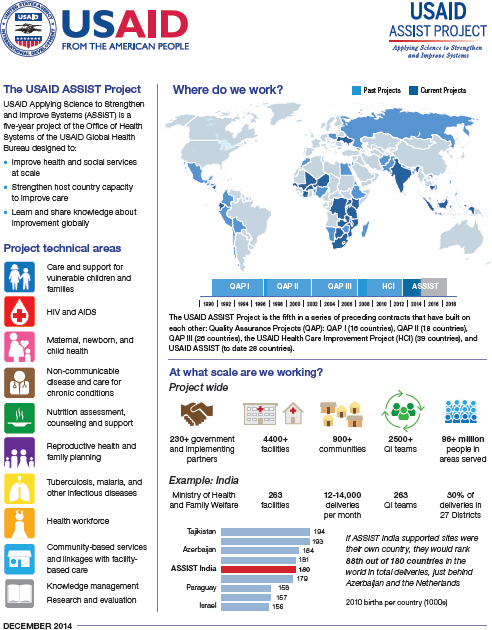

Rashad Massoud, Director, U.S. Agency for

International Development (USAID) Applying

Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems

The USAID Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems (ASSIST) Project is funded by the American people through USAID’s Bureau for Global Health, Office of Health Systems. The project is managed by University Research Co., LLC (URC) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number AID-OAA-A-12-00101. URC’s global partners for USAID ASSIST include: EnCompass LLC; FHI 360; Harvard University School of Public Health; HEALTHQUAL International; Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Initiatives Inc.; Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs; WI-HER LLC; and the World Health Organization Service Delivery and Safety Department. For more information on the work of the USAID ASSIST Project, please visit www.usaidassist.org.

What are we improving at what scale?

USAID Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems University Research Co., LLC, 7200 Wisconsin Ave., Bethesda, MD 20814-4811 USA TEL 301-654-8338 • FAX 301-941-8427 • www.usaidassist.org • assist-info@urc-chs.com

Steve Kelder, Co-Director, Coordinated Approach to Child Health (CATCH)

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

Diffusion of strategies for youth health promotion. This includes preschool, elementary school, and middle school–aged children and adolescents. Specifically, strategies for healthy eating and physical activity that are supported and managed through the CATCH Global Foundation.

CATCH is composed of five main elements: (1) developmentally appropriate classroom instruction for children in grades pre-K–8; (2) physical education activities and continuing education; (3) continuing education for child nutrition services; (4) training, outreach, and involvement of parents; (5) site-based training for program management. See http://catchinfo.org.

Over time we discovered that afterschool programs, YMCA, parks, and recreation programs were interested in the elements of the CATCH school-based program, so we adapted the program and tailored materials and training for those organizations. -

Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

In Texas, 50 percent of public elementary and middle schools report using all or part of the CATCH program (approximately 1.6 million children). We have trained schools, preschools, YMCAs, Jewish community centers, and Boys and Girls Clubs in all 50 states and several other countries. - How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

This is a problem we intend to solve within the coming year. We did not start out to train every school and YMCA in the United States in CATCH; our main target was Texas schools. As our Texas initiative grew, requests for training came from other states, and we did our best to keep up with demand. We did not keep track as we should have. With that said, we conservatively estimate having trained more than 10,000 schools, preschools, and YMCAs. - How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up effort?

This also is a difficult question. Schools are easier to enumerate, because there is a known population of students with small variation within any given school year. However, even adopting schools have varying levels of implementation that is very difficult to track on a large scale.

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

-

- How do you measure this?

In Texas, we have a better estimate of school size from our training logs: We estimate annually reaching approximately 1.6 million students. In other states, the numbers are not well identified, and I should not hazard a guess. What I can say is we have trained schools in all 50 states; in urban, suburban, and rural environments.

-

What proportion of your target population have you reached?

In Texas, approximately 50 percent. Nationally, the number is smaller and I should not guess. A crude guess is 10 percent.- How do you measure this? The Texas Education Agency annually conducts a survey of school district wellness councils and CATCH is consistently reported to be used in approximately 50 percent of schools.

- How do you measure this?

-

What is your ultimate goal?

I’ve been working on CATCH since 1992, as a professor interested in development and evaluation of child health promotion programs. As a professor, the dissemination of CATCH is one of many professional obligations and has not been my full-time job, and funding is inconsistent year to year. To solve some of the problems described above, in 2014 several CATCH investigators started the CATCH Global Foundation, a 501(c)(3) public charity. The mission is to improve children’s health worldwide by developing, disseminating, and sustaining the CATCH platform in collaboration with researchers at University of Texas (UT) Health. The foundation links underserved schools and communities to the resources necessary to create and sustain healthy change for future generations.

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

Our first timeline is to establish the CATCH Global Foundation—we plan on completing initial fundraising and staffing in 2015. As the foundation grows, we anticipate reaching a greater number of underserved schools and families. At this point, I cannot predict how far and fast we will grow, but we have had high-level conversations with many national and international organizations. I’m very optimistic. - How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

CATCH has been a labor of love for me since graduate school in the late 1980s. Throughout my career, I have continued to research and build CATCH starting from an incredible foundation developed by the best child and adolescent researchers in the country. Cheryl Perry, Guy Parcel, Jim Sallis, Johanna Dwyer, Thom McKenzie, and

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

-

-

John Elder, to name a few. My colleague Deanna Hoelscher and I have been at this for a long time.

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

There are three main barriers: (1) reductions in overall school funding nationwide, (2) health objectives are a lower priority relative to educational objectives, and (3) a low profit margin on the delivery of quality training and materials.

-

-

Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your ideas, practices, programs, policies.

In the late 1990s, after the main CATCH randomized controlled trials, we received funding from the Texas Department of Health to disseminate CATCH in Texas. The university also licensed Flaghouse, Inc., to produce, market, and distribute CATCH. Prior to Flaghouse joining our team, we kept CATCH materials in a storage locker in Austin—not the most efficient operation! Our main approach is twofold: (1) We respond to training and implantation requests, and (2) we seek funding from public sources and private philanthropy. Flaghouse markets and warehouses the CATCH program materials and UT faculty maintains quality control over training. The CATCH Global Foundation is now licensed to conduct CATCH trainings and will soon take over maintenance of training and program quality control.-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

We adhere to the diffusion of innovation theory. - What steps did you go through in order to spread a program?

The typical diffusion cycle: increase awareness of the program, locate program champions and innovators, tailor program to local conditions (with reason), train users to implement program, provide technical support, encourage institutionalization of program. - What investment strategies did you use to spread a program?

Most schools and districts have very small health education and physical education budgets, especially in underprivileged schools. We strive to offset school monetary costs with public and private funding. We also have gained UT institutional commitment for allowing faculty to work on CATCH as a professional service. A percentage of faculty salary for program development, evaluation, and dissemination is borne by UT.

- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

- Did you need to make organizational changes to bring something to scale?

Numerous. From production and storage of materials (Flaghouse, Inc.) to the development of the CATCH Global Foundation. -

Were resources already in place to support the scaling strategy or did you need to find special resources to implement the scaling?

UT has been very supportive but could not supply all the resources needed to scale and reach full potential. We needed outside funding and a commercial partner.- If you needed to find additional resources, how did you do it?

Mostly by writing grants and attracting philanthropy dollars.

- If you needed to find additional resources, how did you do it?

Darshak Sanghavi, Director, Population and Preventive Health Models Group at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI)

Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation: Background

CMMI was established by section 1115A of the Social Security Act (as added by section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act). Congress created the innovation center for the purpose of testing “innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce program expenditures … while preserving or enhancing the quality of care” for those individuals who receive Medicare, Medicaid, or Children’s Health Insurance Program benefits.

Congress provided the Secretary of Health and Human Services with the authority to expand the scope and duration of a model being tested through rule making, including the option of testing on a nationwide basis. In order for the secretary to exercise this authority, a model must demonstrate either reduced spending without reducing the quality of care or improved quality of care without increasing spending, and it must not deny or limit the coverage or provision of any benefits. These determinations are made based on evaluations performed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the certification of CMS’s chief actuary with respect to spending.

Established in 2010 and composed of roughly 300 staff members, the center is funded by a $10 billion appropriation over 10 years. Broadly, the center is currently testing models related to accountable care organizations (ACOs) (the Pioneer ACO model), comprehensive primary care, bundled payments for care improvement, state-based innovation models focused on Medicaid, numerous health care innovation awards, and broad based system transformation (e.g., the Partnership for Patients).

Spread and Scale of the Innovation

Annual federal spending by Medicare and Medicaid is approximately $772 billion, and the programs consume 22 percent of the federal budget, covering about 54 million Americans with Medicare and 70 million people via Medicaid. As a result, federal policy in these programs has the potential to drive significant impact through their scale. As of 2013, more than 50,000 providers were engaged by CMMI models, which served more than 1 million Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Typical models can range from 3 to 5 years in duration, though there are several examples of Medicare demonstration projects that have continued for extended periods of time.

The spread and scale of models is typically supported by evaluation, learn/diffusion strategies, and public accountability for results of pilot programs, which are released publicly.

TABLE C-1 Current Model Authorized by the Affordable Care Act (taken from Report to Congress at end of 2012)

| Initiative Name | Description | Statutory Authority | ||

| Accelerated Learning Development Sessions | A series of collaborative learning sessions with stakeholders across the country to inform the design of the accountable care organization initiatives | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Advance Payment ACO Model | Prepayment of expected shared savings to support ACO infrastructure and care coordination | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Bundled Payment for Care Improvement | Evaluate four different models of bundled payments for a defined episode of care to incentivize care redesign Model 1: Retrospective Acute Care Hospital Inpatient Stay Model 2: Retrospective Acute Care Hospital Inpatient Stay & Post-Acute Care Model 3: Retrospective Post-Acute Care Model 4: Prospective Acute Care Hospital Inpatient Stay | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative | Public–private partnership to enhance primary care services, including 24-hour access, creation of care management plans, and care coordination | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Federally Qualified Health Center Advanced Primary Care Practice—Demonstration Financial Alignment Initiative Health Care Innovation Awards | Care coordination payments to FQHCs in support of team-led care, improved access, and enhanced primary care services Opportunity for states to implement new integrated care and payment systems to better coordinate care for Medicare/Medicaid enrollees A broad appeal for innovations with a focus on developing the health care workforce for new care models | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Initiative Name | Description | Statutory Authority | ||

| Initiative to Reduce Preventable Hospitalization Among Nursing Facility Residents | Initiative to improve quality of care and reduce avoidable hospitalizations among long-stay nursing facility residents by partnering with independent organizations with nursing facilities to test enhanced on-site services and supports to reduce inpatient hospitalizations | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Innovation Advisors | This initiative is not a payment and service delivery model for purposes of section 1115A, but rather is an initiative that is part of the infrastructure of the Innovation Center to engage individuals to test and support models of payment and care delivery to improve quality and reduce cost through continuous improvement processes | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Million Hearts | This initiative is not a payment and service delivery model for purposes of section 1115A, but rather is an initiative that is part of the infrastructure of the Innovation Center. Million Hearts is a national initiative to prevent 1 million heart attacks and strokes over 5 years; brings together communities, health systems, nonprofit organizations, federal agencies, and private-sector partners from across the country to fight heart disease and stroke. | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Partnership for Patients | Hospital engagement networks (and other interventions) in reducing HACs/readmissions by 20 and 40 percent, respectively. (Community-Based Care Transition is covered in another row.) | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Pioneer ACO Model | Experienced provider organizations taking on financial risk for improving quality and lowering costs for all of their Medicare patients | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Initiative Name | Description | Statutory Authority | ||

| State Demonstrations to Integrate Care for Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees | Support states in designing integrated care programs for Medicare/Medicaid enrollees | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| State Innovation Models | Provides financial, technical, and other support to states that are either prepared to test, or are committed to designing and testing new payment and service delivery models that have the potential to reduce health care costs in Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

| Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns | Strategy I: Testing the effectiveness of shared learning and diffusion activities to reduce the rate of early elective deliveries among pregnant women Strategy II: Testing and evaluating a new model of enhanced prenatal care to reduce preterm births (less than 37 weeks) in women covered by Medicaid | Section 1115A of the Social Security Act (section 3021 of the Affordable Care Act) | ||

NOTES: This table summarizes the current model tests authorized by Section 1115A of the Social Security Act. ACO = accountable care organization; CHIP = Children’s Health Insurance Program; FQHC = federally qualified health center; HAC = hospital-acquired condition.

Linda Kaufman, National Movement Manager, Community Solutions’ 100,000 Homes Campaign and Zero: 2016

Community Solutions is working on a real-time, data-driven approach to ending homelessness, and it is especially focused on those individuals who are in the most acute need and have been homeless the longest. We view homelessness in America as a public health emergency, as the mortality rate for street homelessness is on par with some forms of cancer, cutting a person’s lifespan by an average of 25 years.

By using learnings from the collective impact and lean start-up models, Community Solutions has quickly spread the work of ending chronic homelessness across the United States by scaling up best practices and embracing targeted, data-driven solutions.

We began with a prototype called Housing First, which provides people experiencing homelessness with housing as quickly as possible and without preconditions, and then provides services to these people as needed. Although developed more than 20 years ago, the Housing First model had not spread far beyond Pathways to Housing, Inc., the developer of the concept. This simple concept has revolutionized the work of ending homelessness.

We then piloted a method of organizing housing services within a community, using the Housing First model to prioritize people based on vulnerability and moving those with the greatest need into housing as quickly as possible. This pilot started in Times Square in New York City and quickly spread to five other vanguard communities across the country (Albuquerque, Charlotte, Denver, the District of Columbia, and Skid Row in Los Angeles). This pilot phase allowed us to develop the right tools and process to house chronically homeless individuals and was pushed forward by the success of these communities.

In July 2010 the national 100,000 Homes Campaign was launched with the help and support of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). Joe McCannon (also a speaker at this forum) was our consultant, guru, and facilitator of many meetings. By learning from IHI’s 100,000 Lives Campaign, we set our sights on an audacious goal—to permanently house 100,000 of our most vulnerable and chronically homeless neighbors and transform the way our communities respond to homelessness. The launch of the campaign allowed us to intentionally target the communities with more than 1,000 chronically (i.e., long-term) homeless individuals.

The spread of this work began in 2010, as we spread the idea to more than 180 communities that went on to house more than 105,000 chronically homeless individuals by July 2014. We made significant changes over the 4 years of the campaign, adopting new techniques and scaling up best practices, and we have seen significant returns on our investments. An independent researcher estimates that each year the system saves

$1.3 billion by moving these 100,000 people from the streets to permanent housing.

By the latter part of the campaign, the spread of these ideas and systematic changes began to reach the scale we had hoped to see. By employing a boot camp model (6 to 10 communities gathered in one place for large-scale change), we were able to go far beyond our previous single-community methodology. The boot camps were first used to introduce communities to prioritization and Housing First, and subsequently they were used to dramatically increase housing placements and system redesign.

Following the successful completion of the 100,000 Homes Campaign, Community Solutions launched a new initiative, Zero: 2016. This rigorous and challenging follow-on to the 100,000 Homes Campaign includes a cohort of 71 communities (including 4 states), which have committed to ending veteran homelessness by the end of 2015 and to ending chronic/long-term homelessness by the end of 2016.

We have moved from working with one community at a time to multiple communities simultaneously. We have moved from simply asking communities to know each person by name to using triage rather than chronology to determine their next housing placement. We have moved from “Set your own goal and see if you can meet that goal” to an objective goal—that 2.5 percent of a community’s chronically homeless population should be housed each month. And now communities have committed to doing the impossible: taking veteran homelessness to functional zero by December 31, 2015, and chronic homelessness to functional zero by December 31, 2016.

Disrupting the failed status quo of “managing” homelessness rather than ending homelessness requires systemic change. That is why we required that all communities applying to be part of Zero: 2016 obtain buy-in from key stakeholders and have a signed memorandum of action in place. Communities had to publicly commit to the goals of Zero: 2016 as well as to a number of community actions aimed at helping reach these goals.

The success of Zero: 2016 is based on the learnings from the prototype and pilot phase, but it is not confined to them. The success of this initiative is based on a constantly iterating process: Data from communities are used to plan and drive subsequent steps, and best practices are identified and adopted. For example, in the 100,000 Homes Campaign, communities were lauded and celebrated for meeting their goals and reporting their monthly housing placements; this had never before been viewed as a useful exercise. Now Zero: 2016 communities recognize that meeting goals and reporting not only are required to participate in the initiative, but also are necessary to reach zero within their communities.

Before the beginning of the 100,000 Homes Campaign and Opening Doors (the federal campaign to end homelessness), we had seen very little success in the reduction of homelessness. Since the federal campaign, supported by the 100,000 Homes campaign, we have seen a 33 percent reduction in the number of homeless veterans and a 20 percent reduction in chronic homelessness. This reduction has been a direct result of a national turn toward the use of evidence-based practices, a reliance on what the data show us, and the amazing federal–private collaborations that have been established along the way. By working with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, we have developed strategic partnerships that have supported our work and impelled us toward meeting the goals of ending veteran and chronic homelessness.

Ogonnaya Dotson-Newman, Director of Environmental Health, West Harlem Environmental Action, Inc. (WE ACT) for Environmental Justice

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

For this example, I will discuss the spread of ideas, programs, and policies directly related to the work of WE ACT for Environmental Justice. WE ACT, based in West Harlem, New York, has been the community health watchdog of Northern Manhattan for more than 25 years. WE ACT’s work bridging research, community organizing, and policy serves as a valuable model for community improvement and change. The two examples of this work that we will use are the spread of ideas and the spread of policies. As an environmental justice organization, WE ACT has worked alongside organizations that do environmental justice work at the national scale. This includes coalition development among organizations, organizing community residents in Northern Manhattan, leveraging relationships through community–academic partnerships, and even engaging local elected officials to create opportunities to improve community health and planning processes. Examples of this include, but are not limited to, the engagement of local residents in the climate march; the engagement of local business owners and residents around garbage, pests, and pesticide issues; negotiation and discussion with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority; and leveraging community organizations, residents, and businesses to close an environmentally hazardous facility. -

Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

- What is the size or scope of the spread/scale up?

WE ACT’s work in relation to size and scale up is at the local community level in most cases. Although the frame is localized, many of the implications of this work can be seen at the city, regional, or even national level, depending on our partners. For example, the implications of the lawsuit filed by WE ACT with the support of Earth Justice related to bittering agents in rodenticides has a national scale. By contrast, the work to sue and engage the Metropolitan Transportation Authority more than 10 years ago with regard to their issues related to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act has more localized implications for community residents in New York City. - How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

- What is the size or scope of the spread/scale up?

-

-

Many of the examples that were given have been created, adopted, and modified on a community-by-community basis by environmental justice organizations. For example, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences had a number of programs in the late 1990s and early 2000s that provided a framework for academic institutions working with community-based organizations. The funding and capacity-building initiatives lead to techniques to improve citizen science and a framework for using science as an organizing tool. Many of the ideas for this framework were tested locally with hundreds of organizations. The wins that you see in cities across the country and even the world are based on programs, policies, and practices developed individually and in collaboration. Some of these examples even build historically on work done and catalogued by movement historians.

- How many individuals have been reached by the scale up?

In some cases, hundreds of thousands of individuals have been reached. For example, much of the work around community–academic partnerships has allowed WE ACT to reach thousands of residents in Northern Manhattan alone. When you multiply this number by the environmental justice organizations across the country and world, the number grows exponentially. - What proportion of your target population have you reached?

By our estimation we have reached a small sliver of individuals through a variety of methods. Given that Northern Manhattan has more than 550,000 residents based on the last census and that WE ACT has a database of a little fewer than 10,000 residents that comes to about 1 percent of the population of Northern Manhattan.

-

-

What is your ultimate goal?

WE ACT’s goal is to improve community health in Northern Manhattan.- What is your timeline for achieving that goal?

There is no timeline for this goal. Because our work often takes a number of years to see measurable change—for example, the Harlem Piers Park took more than 15 years to come to fruition—we envision a healthy, just, and sustainable future for all New Yorkers, and that will take decades to achieve. - How long has it taken to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, and policies to get where you are now?

For the examples I used, there were a variety of timelines to get the policies and ideas scaled up. The Executive Order on Environmental Justice took more than 20 years and then took an additional

- What is your timeline for achieving that goal?

-

-

10 years for the right leaders to be in office at the federal level. The work related to the adoption of policies and practices by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority took more than 15 years. The coalition work and individual organizing around climate justice and climate change issues has taken more than 7 years just in terms of engagement of residents in Northern Manhattan, although the broader coalition and idea spread has been going on for even longer.

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

Coalition building, changing public opinion, and engaging people around issues of social justice are difficult. Power dynamics and social structures that affect institutional racism are all part of the barriers to spreading this work. Identifying key ways to creatively use funding to support community organizing is a continuing barrier. We work hard within our organization and with strategic partners to manage competing interests of the community we serve and to ensure that we are remaining authentic in how we accomplish our goals.

-

-

Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your ideas, practices, programs, policies.

WE ACT uses a variety of ways to disseminate information, and the details vary based on the campaign, initiative, or program. This can relate directly to social marketing, civil disobedience, social media, or just community organizing.-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

WE ACT uses a variety of models to do our work. We use direct organizing when it is needed, we use a community change model, and at times we also use theories that are based in popular education.- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale to spread?

No, WE ACT did not use a particular theory of action or framework of scale to spread. - What steps did you go through in order to spread a program?

WE ACT worked with partners in academic institutions and sometimes government agencies to spread a model. We also worked directly with community-based organizations and individuals through leadership development, mentorship, and internship opportunities, which are always helpful in informing the next generation of social movement leaders in models or ways to get the work done.

- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale to spread?

-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

- What investment strategies did you use to spread a program?

WE ACT continues to invest in local community leaders and individuals in order to have spokespeople and champions for our work. - Did you need to make organizational changes to bring something to scale?

No, we did not make organizational changes. - Were resources already in place to support the scaling strategy or did you need to find special resources to implement the scaling?

Some resources were in place, but much of the work was funded through special funds that were used to increase organizational capacity.

Dan Herman, Professor and Associate Dean, Silberman School of Social Work, Hunter College

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

Critical Time Intervention (CTI) is an individual-level, time-limited care coordination model that mobilizes support for vulnerable persons during periods of transition. It facilitates community integration and continuity of care by ensuring that individuals have enduring ties to their community and support systems during these critical periods. CTI has been applied with veterans, people with mental illness, people who have been homeless or in prison, and many other groups. The model was recently evaluated as meeting the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy’s rigorous “top-tier” standard for interventions: “shown in well-designed and implemented randomized controlled trials, preferably conducted in typical community settings, to produce sizable, sustained benefits to participants and/or society.” -

Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

We engage in active efforts to disseminate CTI directly to provider organizations (e.g., social services agencies, health and mental health providers, housing and homelessness service providers) and to government agencies that fund and oversee delivery of services to vulnerable populations.- How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

We estimate that personnel from more than 200 organizations have been trained, but we lack reliable information on adoption. - How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up effort?

Unknown. We estimate between 3,000 and 10,000 persons. We currently have no way to measure this. - What proportion of your target population have you reached?

Unknown. - How do you measure this?

We have no way to measure this right now. It is possible that in future work within specific service delivery systems (i.e., funding auspices, geographical entity) we may be able identify targets for spread and assess how far along we are toward attaining these targets.

- How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

-

What is your ultimate goal?

The goal right now is to continue broad dissemination in multiple systems. No numerical goal has been identified.

-

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

No timeline has been established. - How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

The original demonstration research project (funded by the National Institutes of Health) began in 1991 and ended in 1996, with results published in 1997. Further research and dissemination has been continuing since that time. -

What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

- A lack of a single funding mechanism that can support model implementation across service delivery sectors and in a variety of local communities.

- Difficulty in getting the word out to potential funders and adopters.

- A lack of funding support for dissemination, training, and implementation support activities.

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

-

Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your ideas, practices, programs, policies.

As researchers, we relied originally on publishing in academic journals and presenting at professional conferences. Over the past several years, we have developed partnerships with training organizations whose primary mission is to train social services and health care providers in evidence-based practices. Most recently, with support provided by the Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College, we have launched a Center for the Advancement of Critical Time Intervention (CACTI) in partnership with our organizational collaborators. The purpose of CACTI is to support the broad dissemination of CTI and to ensure quality and fidelity in its implementation. The center sponsors the CTI Global Network to promote collaboration among CTI practitioners, trainers, and researchers on promising adaptations and enhancements to the model.- What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies? Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

We have not employed a particular theory to promote spread. Our activities have been largely ad hoc up until this point. However, we have been informed by general principles of implementation science that are consistent with the work of Fixsen and others who have emphasized the need for careful consideration of drivers and barriers to effective implementation. We have also been influenced by the literature on diffusion of innovation.

- What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies? Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

- What steps did you go through in order to spread a program?

As noted above, we initially focused on diffusing information about the model via traditional professional literature channels. More recently we have supplemented this by partnering with for-profit and nonprofit organizations whose business models rely on selling training and implementation support for a variety of evidence-based practices, including CTI. Our launch of a center dedicated to promoting effective dissemination of the model is the next step in this process. - What investment strategies did you use to spread a program?

- Did you need to make organizational changes to bring something to scale?

As described above, we have launched a center dedicated to the dissemination of and support for the model. - Were resources already in place to support the scaling strategy or did you need to find special resources to implement the scaling?

Resources were not in place. We are currently attempting to identify resources to support continued dissemination. The options we are exploring include seeking public and private funding as well as obtaining revenue from trainers and providers via certification or accreditation approaches. We expect this to be a significant challenge.

Cheryl Healton, Dean, New York University, Global Institute of Public Health

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

Two principal forms of public education were undertaken by Legacy’s truth® campaign and BecomeAnEX in partnership with other foundation funders and the states. The truth® campaign is focused on the primary prevention of smoking, while BecomeAnEX is focused on motivating people to quit and giving them tools to do so. The truth® campaign aims to empower teens to make an informed choice about starting to smoke through understanding the behavior of the tobacco industry toward teens (e.g., the truth about its marketing practices). The EX campaign, no longer airing, was focused on raising national awareness among smokers about their own efficacy with respect to quitting, and it sought to motivate quit attempts via the BecomeAnEX website (still operating) and through other means. -

Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

National public education to prevent tobacco use is now undertaken by three main entities: truth®, which is back on the air at a fairly high paid media buy level; the U.S. Food and Drug Administration youth smoking prevention campaign; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tips from Former Smokers campaign, which, while mainly focused on smokers, reaches youth as well. The scale of these campaigns is considerable in that they reach virtually the entire television viewing public in their target groups at high frequency. For most media campaigns, social media plays a key and increasing role. Breaking through the “clutter” remains a challenge for all campaigns, especially those not focused on a product but rather on complex behavior change of some sort.- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

For truth® and EX, more than 75 percent of the entire national population target (teens and smokers) was reached. Both campaigns also have Web and other social media activity, which includes opportunities to share content with other teens and other smokers (for EX). - How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

These campaigns were national in scope, but a number of states have subsidized the EX campaign, and many have used EX ads locally. The campaigns have not been replicated outside the United States.

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

-

-

How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up effort?

For truth® about 75 percent of teens could describe at least one ad during 2000–2004, about 50 percent during 2004–2007, and less thereafter as the campaign relied more on social media and had less to spend on the national media buy. The new truth® campaign, Finish It, is currently being assessed with regard to reach and impact.- How do you measure this?

The truth® campaign’s reach and frequency was measured by multiple waves of national sampling to determine what percentage of teens viewed the campaign and, on average, how many exposures they had. The campaign was also assessed on receptivity, “talking to friends about,” and on impact on smoking rates. A similar approach was used for EX to estimate its reach, which was about 75 percent of smokers.

- How do you measure this?

- What proportion of your target population have you reached?

For truth®, the vast majority—75 percent—could describe specific ads; also 75 percent for EX, which had a shorter duration media buy—two 6-month intensive periods. Both campaigns had significant impact. truth® was responsible for at least 22 percent of the decline in smoking from 2000 to 2004, resulting in an estimated 450,000 youths not starting. EX was associated with a 24 percent greater likelihood of a quit attempt among those who recalled the campaign.

-

How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up effort?

-

What is your ultimate goal?

Reducing smoking initiation and helping people quit.

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

Ongoing national Healthy People goals would be nice to reach, but the adult goal is still out of reach despite the many related efforts ongoing, such as price increases, clear air laws, etc. - How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

It has taken decades for funded national tobacco-use-related public education to be undertaken. The period from 1968 to 1971 was the first time that any national public tobacco education aired on television. This campaign was achieved via donated air time required by the Fairness Doctrine. truth® was the next national campaign (2000 to present). The CDC Tips campaign was the first federally funded public education campaign. A number of states have run campaigns, most consistently California.

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

-

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

The Master Settlement Agreement allowed for state settlement funds to go to Legacy for only 10 years. The Foundation can fund truth® only by using reserve funds, which could be depleted if the campaign is funded at high levels for a sustained period. The tobacco industry sues to disrupt public education and works against tobacco control in a variety of ways. The tobacco industry seeks to obstruct blunt public education.

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

-

Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your ideas, practices, programs, policies.

Encouraging states to adopt; encouraging media networks to subsidize, as they do anti-drug messages; encouraging other public education efforts, and collaborating with them.

-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your (ideas, practices, programs, policies)?

The main theory underlying the truth® campaign is focused on youth “need states” associated with maturation. Young people seek to reject old ideas and adopt new ones for themselves. truth® used a “branded” approach—“Their brand is lies, our brand is truth”—in order to capitalize on the natural rebelliousness of teens, especially risk-taking teens open to smoking. Research has shown that “sensation-seeking” teens are more open to multiple risky behaviors including smoking; for this reason, the campaign was designed for this group.

EX relies mainly on the theory of reasoned action and efficacy theories of health behavior change.

- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

See Figure 5-1. - What steps did you go through in order to spread a program?

The program was spread using paid mass media and social media as well as “earned” media (free coverage). - What investment strategies did you use to spread a program?

We invested in legal fees to fight the tobacco industry effort to shut down the campaign. We invested in efforts to encourage others to co-fund campaigns and to develop others at the state, local, and national levels. - Did you need to make organizational changes to bring something to scale?

Yes—it can only happen with more money from government or private sources.

- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your (ideas, practices, programs, policies)?

-

Were resources already in place to support the scaling strategy, or did you need to find special resources to implement the scaling?

Yes, but not sufficient over time.- If you needed to find additional resources, how did you do it?

We raised funds from federal and state government to extend truth® to rural under-reached areas and to co-fund EX.

- If you needed to find additional resources, how did you do it?

Brian King, Senior Scientist, Office of Smoking and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

We know what works to effectively reduce tobacco use, and if we were to fully invest in and implement these proven strategies, we could significantly reduce the staggering toll that tobacco takes on our families and in our communities. Evidence-based, statewide tobacco control programs that are comprehensive, sustained, and accountable have been shown to reduce smoking rates as well as tobacco-related diseases and deaths. This comprehensive approach combines educational, clinical, regulatory, economic, and social strategies. Research has documented the effectiveness of laws and policies in a comprehensive tobacco control effort to protect the public from secondhand smoke exposure, promote cessation, and prevent initiation, including increasing the price of tobacco products, implementing and enforcing smoke-free laws, warning about the dangers of tobacco use with antismoking media campaigns, and increasing access to help quitting. Additionally, research has shown greater effectiveness with multicomponent interventional efforts that integrate the implementation of programmatic and policy initiatives to influence social norms, systems, and networks. -

Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

Proven population-based tobacco prevention and control interventions, including increasing the price of tobacco products, implementing and enforcing smoke-free laws, warning about the dangers of tobacco use with antismoking media campaigns, and increasing access to help quitting can be and are being implemented at the national, state, and local levels. - How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

To date, all 50 states have tobacco control programs; however, only two (Alaska and North Dakota) currently fund tobacco control programs at CDC-recommended levels. Moreover, the adoption of proven population-based tobacco control strategies varies by state. To date, 26 states have comprehensive smoke-free laws prohibiting smoking in indoor areas of worksites and public places, including restaurants and bars; all 50 states have cigarette excise taxes, but wide variability exists (from 17 cents per pack in Missouri to $4.35 per pack in New York); the implementation of antismoking media campaigns varies by state, with some states relying solely on fed-

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

-

-

eral campaigns (e.g., Tips from Former Smokers); all 50 states have a tobacco quitline, but the services rendered (e.g., free nicotine patches) vary across states.

- How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up effort? How do you measure this?

The reach of proven tobacco prevention and control interventions varies by state, with implementation being greater in states with lower tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure. At present, more than 150 million U.S. residents are covered by statewide and local laws prohibiting smoking in indoor areas of worksites and public places, including restaurants and bars. Moreover, people buying cigarettes in all states must pay cigarette excise taxes, with the exception of those buying cigarettes on Native American reservations; however, variability exists across states. Coverage is typically assessed using a combination of legislative tracking systems and self-reported data from public health surveillance systems along with population data from the U.S. Census Bureau. - What proportion of your target demographic have you reached? How do you measure this?

Population coverage of proven tobacco prevention and control interventions also varies by state. For example, approximately 50 percent of the U.S. population is covered by statewide and local laws prohibiting smoking in indoor areas of worksites and public places, including restaurants and bars. Coverage is typically assessed using a combination of legislative tracking systems and self-reported data from public health surveillance systems along with population data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

-

-

What is your ultimate goal?

Healthy People provides science-based, 10-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans. For three decades, Healthy People has established benchmarks and monitored progress for national objectives. The Healthy People goal for tobacco is to reduce illness, disability, and death related to tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure; there are 20 objectives to assess progress toward this goal (www.healthypeople.gov).- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

Healthy People 2020, which was launched in December 2010, continues the tradition of the program’s ambitious, yet achievable, 10-year agenda for improving the nation’s health. For all 20 tobacco-related objectives, specific targets have been established for expected achievement by the year 2020.

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

-

- How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

In January 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General released the first report on smoking and health—a landmark federal document linking smoking to lung cancer and heart disease in men. This scientifically rigorous report laid the foundation for tobacco prevention and control efforts in the United States. Since 1964, a considerable body of scientific evidence coupled with national and state tobacco control experiences has developed. We now know what works to effectively prevent and reduce tobacco use; however, these strategies are not fully implemented in many states and the tobacco landscape continues to evolve. Most recently, the 50th anniversary Surgeon General’s report outlined a retrospective of tobacco control over the past five decades, as well as a summary of proven strategies to curtail the tobacco epidemic. - What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

Many state programs have experienced and are facing substantial state government cuts to tobacco control funding, resulting in the near-elimination of tobacco control programs in those states. In 2014, despite combined revenue of more than $25 billion from settlement payments and tobacco excise taxes for all states, states will spend only $481.2 million (1.9 percent of that total) on comprehensive tobacco control programs, which is less than 15 percent of the CDC-recommended level of funding. Moreover, only Alaska and North Dakota currently fund tobacco control programs at CDC-recommended levels. To complicate matters, the tobacco industry spends more than $8 billion each year, or $23 million per day, to market cigarettes in the United States.

- How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

-

Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your ideas, practices, programs, policies.

-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your idea, practices, programs, policies?

Multiple models and theoretical frameworks exist for the purposes of health promotion and may be applied in the context of tobacco control interventions. Identifying a model or theoretical framework depends on the factors that are to be addressed and the setting in which the intervention or program will take place.- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

Some of the most commonly used theoretical frameworks in the context of tobacco control include, but are not limited to, the transtheoretical model, the theory of planned behavior, and

- Have you used a particular theory of action or framework of scale or spread?

-

What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your idea, practices, programs, policies?

-

the social-ecological model. The development of workplace tobacco control interventions may be informed by a single model or theoretical framework, or it may encompass more than one.

- What steps did you go through in order to spread a program?

The continuum of change associated with implementing tobacco prevention and control interventions typically starts with increasing people’s knowledge of the benefits of such interventions, changing their attitudes toward the acceptability of tobacco use and exposing non-smokers to secondhand smoke, and enhancing their favourability toward these interventions. Such changes can lead to increases in the adoption of, and compliance with, tobacco control interventions as people become more conscious of their public health benefits. Although statewide interventions provide greater population coverage than local restrictions, the strongest protections have traditionally originated at the local level. These laws and interventions have typically spread to multiple communities throughout a state and lay the groundwork for statewide laws and interventions. - What investment strategies did you use to spread a program?

CDC’s Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2014 is an evidence-based guide to help states plan and establish comprehensive tobacco control programs (www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices). This report describes an integrated budget structure for implementing interventions proven to be effective and the minimum and recommended state investment that would be required to reduce tobacco use in each state. In the report, the annual investment needed to implement the recommended components of a comprehensive program ranged from $7.41 to $10.53 per capita across the 50 states and Washington, DC. - Did you need to make organizational changes to bring something to scale?

We know what works to effectively reduce tobacco use, and if we were to fully invest in and implement these proven strategies, we could significantly reduce the staggering toll from tobacco use. States that have made larger investments in comprehensive tobacco control programs have seen larger declines in cigarettes sales than the United States as a whole, and the prevalence of smoking among adults and youth has declined faster as spending has increased. Additionally, the longer states invest in such programs, the greater and quicker

-

the impact. Therefore, organizational changes to fully implement and sustain comprehensive tobacco control programs at CDC-recommended levels are critical to make the organizational changes required to effectively achieve Healthy People 2020 goals.

- Were resources already in place to support the scaling strategy, or did you need to find special resources to implement the scaling?

CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health created the National Tobacco Control Program in 1999 to encourage coordinated, national efforts to reduce tobacco-related diseases and deaths. The program provides funding and technical support to state and territorial health departments, including all 50 states, Washington, DC, 8 U.S. territories, 6 national networks, and 8 tribal support centers. However, state resources are also required to fully fund and sustain comprehensive tobacco control programs; this funding varies by state. In fiscal year 2014, the states will collect $25 billion in revenue from the tobacco settlement and tobacco taxes, but will spend only 1.9 percent of it on programs to prevent kids from smoking and help smokers quit. This means the states are spending less than 2 cents of every dollar in tobacco revenue to fight tobacco use.

Jeannette Noltenius, member of the National Latino Alliance for Health Equity, the National Latino Tobacco Control Network, and the Phoenix Equity Group, but statement is my own.

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

As Latino networks and as part of the Phoenix Equity Group we promote reducing tobacco use, healthy eating, active living, and health equity. (1) Data collection, use, and dissemination by subgroups is essential to understanding how to reach/engage/mobilize the diverse members of our nation and future generations: one in four youth is Latino, two out of four are minorities, and in 2043 the nation will be majority/minority (http://nationalequityatlas.org). (2) Health equity is about social justice, inequities are growing, and structural racism and social determinants of health have to radically change to improve health in America. Place matters, housing segregation impacts health. (3) Comprehensive approaches should not only be about policies (private, public, local, state, federal: raising taxes, smoke-free air, cessation, restriction of ads, sales to minors, strong product regulation, etc.), but should also focus on local engagement, multi-ethnic leadership, capacity building, and targeted media campaigns. There is no silver bullet, policies do not affect populations equitably, they may have an immediate impact but leave many behind. (4) There is limited interest in and therefore limited funding for research projects that focus on specific priority populations. Population-level interventions do not necessarily work for priority populations, and there is limited evidence for what does work. (5) There are promising practices that reach these populations, but these need to be systematically evaluated and replicated (www.appealforhealth.org, www.latinotobaccocontrol.org, www.legacyforhealth.org). (6) Funding for leadership and capacity building is essential to achieve and defend gains at all levels. (7) Multi-ethnic and lesbian/gay/bisexual/transsexual (LGBT) efforts have to be supported to create political power. Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) funds, state funds raised from taxes, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and foundation funds have to be destined to reach the most vulnerable and the growing racial, ethnic composition of the nation, the poor, and those suffering from mental health issues and substance abuse. - Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

National means inclusive of U.S. territories, jurisdictions, and Indian nations and reaching all segregated, marginalized communities. Scale up means reaching all. It is not about one policy or one ad

for each group; it is about different actors, messages, and messengers. It means integrating leadership so as to represent the changing demographics and perspectives, equitably distributing resources, and changing the focus of population-based approaches to reach those left behind.

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

Unfortunately, funders think that funding one or several national racial/ethnic networks at $400,000 to $700,000 per year means they are “reaching” all minorities. This is a false premise because policies, programs, and efforts need to have depth and breadth and have everyone focusing on those left behind in pockets of poverty and segregation. Media is segmented, and industries target certain groups; funders need to do the same. - How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs and practices, etc.)?

Listservs, newsletters, and information reach 10,000 people, but active participants are around 500 for Latinos and maybe 4,000 overall. Networks are ineffective if groups do not have funds to act locally. In Minnesota with Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Minnesota and Department of Health funding, Latinos and others have adopted tobacco-free policies in more than 200 apartment buildings; in churches, day care centers, restaurants, businesses; in two colleges; as well as healthy eating and active living policies (healthy options, labels, bike racks, built environment, farmers markets, etc.). ClearWay Minnesota has funded the Leadership and Advocacy Institute to Advance Minnesota’s Parity for Priority Populations program and has obtained policy results. Minnesota has made achieving health equity a goal. But funding has been eliminated in Washington and Ohio, where leadership was being built and mobilized, and has dwindled in California, Colorado, Florida, Indiana, Maryland, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Texas, and most states, so many community-based organizations are no longer working on policies or programs. Smoke-free policies in New York and California did not affect businesses with fewer than five employees where many minorities work. The President signed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act that gave FDA authority over regulating tobacco. But mentholated cigarettes, which are used heavily by African Americans, Native Hawaiians, and youth (as a starter cigarette), were not included in the law, and after 5 years these are yet to be regulated or banned. Flavored cigarettes were eliminated, but the industry created flavored cigarillos and cigars (used by minority youth) that can be individually purchased and are cheaper. So the products favored

-

-

by minorities and vulnerable youth have not been regulated or taxed appropriately. E-cigarettes, hookah, and smokeless products are invading the market. More than 98 percent of MSA funds and most of the cigarette taxes have not been used for tobacco control. We failed to make an impact on politicians as to why progress is stalled, and industry tactics have adjusted by marketing multiple products.

- How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up efforts? How do you measure this?

We counted towns, cities with large minority populations that went smoke free, housing developments, schools, churches, etc., and the prevalence of youth and adult in Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and household surveys done by federal agencies. But these surveys do not gather data by subgroups or report on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Native Americans, or LGBTs. More data and research is needed for dissemination and use! - What proportion of your target population have you reached? How do you measure this?

We cannot measure the impact of policies in an in-depth manner. Prevalence is only one measure. We can measure how many media outlets and messages are sent and how many people call quitlines, but not necessarily whether clean indoor air policies are effective, enforced, accepted, and whether people quit all tobacco products, nor whether norms have changed systemically in communities of color, LGBT, reservations, territories, in homeless shelters, public housing, etc.

-

-

What is your ultimate goal?

- What is our timeline for achieving the goal?

A world where the disparate needs of diverse communities are measured, addressed, and resolved in an equitable manner. We will start with focusing on commercial tobacco use; equitable tobacco control prevention and control outcomes and promoting systems change that values equity at its core and inclusion of communities affected (Phoenix Equity Group). - How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

Several of our leaders started with the ASSIST program in 1991, with funding from the CDC Office of Tobacco and Health for national networks in 1994, and with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s network initiative in 1997. All funding has ebbed and waned.

- What is our timeline for achieving the goal?

-

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

Many national Latino and minority organizations and political leaders have received tobacco, fast food, alcohol, and soda industries funding or sponsorship and therefore are beholden to them. At the local, state, and federal levels, policy initiatives have been opposed by these groups and politicians. Public heath funders have not systematically helped these groups and individuals divest themselves of this funding. Mainstream organizations, governments, and foundations have not considered the importance of engaging racial/ethnic minority groups in their decision-making process, policy development, or actions. Tobacco control, active living, and healthy eating are not priorities in minority communities because they are dealing with jobs, housing, education, immigration, and law enforcement. Engagement in the political process is still in its infancy in some communities. Anti-immigrant sentiment, discrimination, and homophobia have dampened engagement in some states, and fear of deportation or reprisals is real, yet events have energized some groups.

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

-

Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your ideas, practices, programs, policies.

Minority leaders writing in minority news outlets or appearing on television create local echo effects that impel local politicians to act responsibly and support systemic policy changes.

- What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

Apply models of readiness by Asian Pacific Partners for Empowerment, Advocacy & Leadership, go to where communities live, work, play, pray, and build leadership.

- What theory/approaches do you use to get people to adopt your ideas, practices, programs, policies?

Sally Herndon, Director, North Carolina Tobacco Prevention and Control Branch (TPCB)

- Describe what you are spreading (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

The North Carolina TPCB works with partners to spread evidence-based practices in tobacco prevention and control. We promote all strategies recommended by the Guide for Community Preventive Services and CDC’s Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs—2014. This includes changing social norms through policy, particularly to raise the price of tobacco products, making all workplaces and public places smoke free, and adequately investing in tobacco prevention and control strategies, including state and community interventions, mass reach health communication, tobacco cessation interventions, surveillance and evaluation, and infrastructure, administration, and management. For today’s panel discussion, I will focus mostly on spreading smoke-free policies, as that is where North Carolina has made the most progress. -

Please explain what spread and scale means in the context of what you do.

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

North Carolina tobacco control partners are working to make all workplaces and public places smoke free. We do this incrementally without closing doors on future progress. - How many organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, communities, etc.) have adopted the strategies (programs, practices, etc.)?

Despite passage of the preemptive state law, TPCB worked with North Carolina Alliance for Health, the Justus–Warren Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention Task Force, and other networked partners to make incremental changes in social norms and policy, making the North Carolina General Assembly smoke free (2006), and then all state government buildings and vehicles 100 percent tobacco free, long-term care facilities smoke free (2007), all public schools 100 percent tobacco free (2008), all state prisons 100 percent tobacco free (2009), and all long-term care facilities smoke free (2007). North Carolina became the first southern state to pass a law to make all restaurants and bars smoke free (2010). This law also reinstated the authority of local governments to make government buildings, grounds, and public places smoke free, with public places defined as indoor spaces where the public is invited inside. North Carolina communities have risen to this opportunity, passing 816 county and municipal regulations since preemptive legislation was lifted in 2010. North Carolina has 38 smoke-free public housing properties and 274 smoke-free affordable housing

- What is the size or scope of the scale up/spread?

-

-

properties. More than half (35 of 58) of North Carolina community colleges are 100 percent tobacco free.

- How many individuals (e.g., clients, patients, students, etc.) have been reached by the scale up effort? How do you measure this?

Previously, we have counted policies, laws, and government regulations. We are working to add counts of the numbers of people protected from secondhand smoke in these venues. Southern states (the least likely to protect all people from tobacco smoke) will be meeting with CDC next week to determine some uniform measures for this. - What proportion of your target population have you reached? How do you measure this?

The North Carolina Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (2013) shows that 10 percent of adults are exposed each week to secondhand smoke in the workplace, and 15 percent of adults are exposed to secondhand smoke by someone smoking in their home. In addition, 11.7 percent of adults report being exposed to secondhand smoke in the home from smoke drifting from another apartment or from outdoors. The North Carolina Youth Tobacco Survey (2013) reports that 13.6 percent of high school students are exposed to secondhand smoke in the home, and 18.4 percent report exposure in vehicles.

-

-

What is your ultimate goal?

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

To eliminate exposure to secondhand smoke in North Carolina by 2020. - How long has it taken you to scale up the ideas, practices, programs, policies to get where you are now?

TPCB was first funded under the America Stop Smoking Intervention Study (ASSIST) project of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 1991. Prior to the intervention stage, which began in 1994, the North Carolina General Assembly passed “preemptive” legislation requiring that North Carolina set aside 20 percent of state government buildings for smoking, as practicable, and that local governments could not pass more restrictive regulations. Core funding moved from NCI to CDC in 1999. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded tobacco control initiatives (SmokeLess States) and a Youth Tobacco Use Prevention Grant for North Carolina, and the American Legacy Foundation funded a North Carolina Youth Empowerment Grant. These funds greatly benefited North Carolina’s work in tobacco use prevention and control. In 2002, the North Carolina General Assembly created the North Carolina

- What is your timeline for achieving the goal?

-

-

Health and Wellness Trust Fund with Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement funds to focus primarily on teen tobacco use prevention and cessation. The North Carolina Health and Wellness Trust Fund budgeted between $6.2 million and $18 million per year before they were abolished by the North Carolina General Assembly in 2011.

- What barriers have limited your success in reaching your goals?

Let me first emphasize the positive factors to produce spread and scope. Facilitators have included using engaged data, networked partners, and multi-level leaders to advance evidence-based policies. Engaged data include the sound science of the health and economic impact of secondhand smoke on populations, communities at risk, and maps and charts of where policies have been passed. Effective champions often include not only experts and officials, but also survivors and victims. The most common barrier today is that the political will is lacking to impose regulations on private sector businesses.

-

- Describe your approach to disseminating/spreading your (ideas, practices, programs, policies).

North Carolina tobacco control partners have strived to employ an interactive tobacco control infrastructure called the component model of infrastructure and its five interrelated core components: multilevel leadership, managed resources, engaged data, responsive plans and planning, and networked partnerships. North Carolina partners have approached the spread of smoke-free/tobacco-free policies by emphasizing the health and economic benefits of these regulations. The North Carolina partners have used the diffusion of innovation theory in taking an incremental and at times opportunistic approach to make progress toward the goal of eliminating exposure to secondhand smoke. A strategic planning resource called Nine Strategies Questions is used to take steps including identifying the goal, the decision makers, and how to reach them, and building support using the data on the health and economic impact along with key spokespersons from those communities to share the benefits with others like them. For example, we facilitated workshops for schools that went 100 percent tobacco free campus-wide to tell their success stories to other school districts. Soon, hospitals saw the need to do this as well. TPCB mapped the progress, and when the percentage of schools adopting a tobacco-free policy reached the tipping point, a well-respected senator who was also a family physician from eastern North Carolina introduced legislation to require the remaining school districts to adopt a

-

100 percent tobacco-free policy, and hospitals followed suit in a similar manner with help from North Carolina Prevention Partners and a Duke Endowment grant. All state-operated mental health, developmental disabilities, and substance abuse treatment facilities became 100 percent tobacco free campus-wide in 2014, and these facilities are actively integrating tobacco cessation into treatment, where just a few years ago cigarette use was tolerated, if not encouraged, as patients worked on alcohol and other drug abuse problems.