Pathways to Urban Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities for the United States (2016)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

Cities have experienced an unprecedented rate of growth in the past decade. More than 50 percent of the world’s population lives in urban areas, with the U.S. percentage at 80 percent. Cities have captured more than 80 percent of the globe’s economic activity and offered social mobility and economic prosperity to millions by clustering creative, innovative, and educated individuals and organizations. Clustering populations, however, can compound both positive and negative conditions, with many modern urban areas experiencing growing inequality, debility, and environmental degradation.

The spread and continued growth of urban areas presents a number of concerns for a sustainable future, particularly if cities cannot adequately address the rise of poverty, hunger, resource consumption, and biodiversity loss in their borders. Cities already place a large stress on the planet’s resources by emitting more than 75 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, though on a per capita basis the emissions on cities tend to be lower (Dodman, 2009). In addition, a large proportion of the world’s population with unmet needs lives in urban areas. Thus, any discussion of sustainable development should center on cities and how to capitalize on their positive energy and innate diversity in forging new pathways toward urban sustainability.

Urban sustainability practitioners and scholars regularly develop and apply a variety of innovative methods. Assessing the spectrum of new practices that have been implemented in specific metropolitan regions provides insight into whether and how other urban areas might adapt and apply these methods. Applying such new methods and practices additionally calls for an understanding that cities exist within the larger contexts of the planet’s finite resources; thus, achieving urban sustainability requires recognizing interconnections among places and the associated impacts of actions.

As such, this study committee was tasked with examining various areas within metropolitan regions to understand how sustainability practices could contribute to the development, growth, and regeneration of major metropolitan regions in the United States. The committee was also tasked with the aim of providing a paradigm incorporating the social, economic, and environmental systems within the urban context that are critical in the transition to sustainable metropolitan regions which could then serve as a blueprint for other regions with similar sustainability challenges and opportunities. In addition to the development of a paradigm incorporating the critical systems needed for sustainable development in metropolitan regions, the committee’s task included a focus on

- How national, regional, and local actors are approaching sustainability;

- How stakeholders can better integrate science, technology, and research into catalyzing and supporting sustainability initiatives; and

- The commonalities, strengths, and gaps in knowledge among rating systems that assess the sustainability of metropolitan regions.

Finally, the committee’s task included the organization of a series of public data-gathering meetings to examine issues relating to urban sustainability, culminating in findings and recommendations that describe and assess

- The linkages among research and development, hard and soft infrastructure, and innovative technology for sustainability in metropolitan regions;

- The countervailing factors that inhibit or reduce regional sustainability and resilience;

- Future economic drivers, as well as the assets and barriers to sustainable development and redevelopment; and

- How federal, state, and local agency and private-sector efforts and partnerships can complement and/or leverage the efforts of key stakeholders.

Intended as a comparative illustration of the types of urban sustainability pathways and subsequent lessons learned existing in urban areas, this study examines specific examples that cut across geographies and scales and that feature a range of urban sustainability challenges and opportunities for collaborative learning across metropolitan regions. The study committee chose nine cities: Los Angeles, California; New York City, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Grand Rapids, Michigan; Flint, Michigan; Cedar Rapids, Iowa; Chattanooga, Tennessee; and Vancouver, Canada. These cities were selected to represent a variety of metropolitan regions, with consideration given to city size, proximity to coastal or other waterways, susceptibility to hazards, primary industry, water scarcity, energy intensity and reliability, vertical density, transportation system performance, and social equity issues. The committee chose two cities, Los Angeles and Chattanooga, as the sites for its public data-gathering meetings due to their diverse characteristics in terms of size, geography, and varied sustainability challenges, such as water and air quality.

THE CHALLENGE OF URBAN SUSTAINABILITY

This report first describes the concept and challenges of the pathways to becoming a “sustainable city.” Cities concentrate people, investment, and resources, which, despite the potential for positive consequences in the form of creativity, economic development, and social and community well-being, also can be associated with negative consequences for air and water quality, ecosystem viability, poverty rates, and high rates of wealth inequity. Sustainability of urban areas therefore encompasses a range of interconnected environmental, economic, and social issues. Additionally, sustainability of urban areas also requires the adoption of a geographic scope that incorporates those ecosystems and people existing outside of immediate urban areas, such as hinterlands and rural regions, which are affected by urban consumption and demands.

The committee defines urban sustainability as the process by which the measurable improvement of near- and long-term human well-being can be achieved through actions across environmental (resource consumption with environmental impact), economic (resource use efficiency and economic return), and social (social well-being and health) dimensions. Measuring the dimensions of urban sustainability has proven as challenging as defining the concept. This report provides a meta-review of a set of indicators and metrics that the committee selected from a large pool of publicly available data. The goal is to select a subset of urban sustainability indicators that help identify problems and pressures to provide useful information for policy intervention by urban communities. The selected indicators represent urban sustainability’s three dimensions of environment, economy, and society (see Figure 2-1), including air quality, water quality, ecological footprints, financial health, infrastructure, education, and community health. These indicators do not operate in isolation; rather, they operate synergistically. Additionally, a fourth dimension of metrics is put forward to consider institutional capacities and governance issues as an important area for future research.

A ROADMAP TO URBAN SUSTAINABILITY

With their convergence of people and resources, cities are not sustainable without the support of ecosystem services and products from nonurban areas, including those long distances away. Because each city is also linked into the global system of cities, actions taken in one place will likely have effects in other places. The sustainability of a city cannot be considered in isolation from the planet’s finite resources or from the city’s interconnections with other places. As such, pathways toward urban sustainability must adopt a multiscale approach that highlights resource dependencies and cities’ interlinkages. Within this context, this study presents four main principles, as heuristics, to promote urban sustainability:

-

Principle 1 – The planet has biophysical limits

Urban activities use resources and produce byproducts such as waste and GHG emissions which drive multiple types of global change, such as resource depletion, land-use change, habitat and biodiversity loss, and global climate change. What may appear to be sustainable locally, at the metropolitan scale, belies the total planetary-level environmental or social consequences of local actions. Thus, strategies aimed at urban sustainability must pay heed to biophysical limits at the planetary scale. One way to do this is to try to reduce the city’s metabolism, which is constituted by the material and energy that flows in and out of cities. A city cannot reduce its footprint by exporting carbon-intensive activities to other areas.

-

Principle 2 – Human and natural systems are tightly intertwined and come together in cities

Healthy people, healthy biophysical environments, and healthy human-environment interactions are synergistic relationships that underpin the sustainability of cities. Incorporating diverse community interests into sustainability planning and decision making is required in order to facilitate both healthy human and natural ecosystems. Cities, especially large ones, are connected to natural systems, not just locally but globally.

-

Principle 3 – Urban inequality undermines sustainability efforts

Reducing severe economic, political, class, and social inequalities is pivotal to achieving urban sustainability. Efforts to reduce these inequalities and make cities more inclusive help cities realize their full potential, making them appealing places to live, work, and improve prospects for economic development. Long-term policies and institutionalized activities can promote greater equity and contribute to the future of sustainable cities.

-

Principle 4 – Cities are highly interconnected

Cities are not islands. They are complex networks of interdependent subsystems that are affected by decisions and institutions across different spatial scales and in other localities. Cities require resources that come from other places and are affected by decisions and stakeholders in these places. Making cities livable, economically competitive, and sustainable demands new models of governance, institutions, and innovative partnerships that can address multiple dimensions of a city’s connections with other places, stakeholders, and decision making. A multiscale governance system that explicitly focuses on interconnected resource chains and places is essential to transition toward urban sustainability.

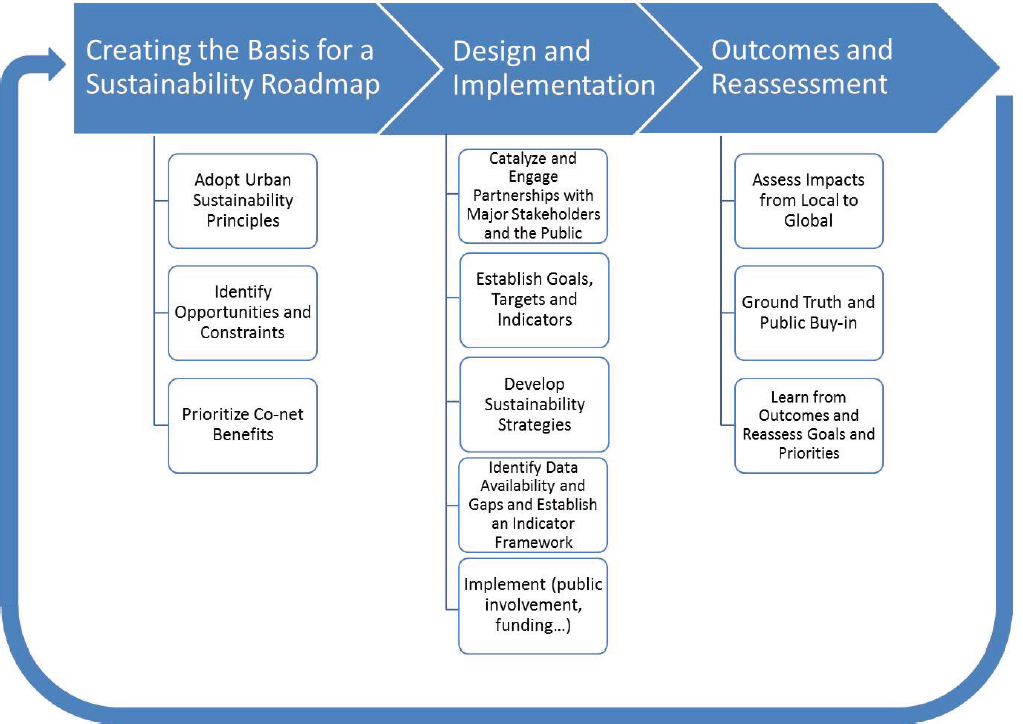

This study constructed a comprehensive strategy in the form of a roadmap that incorporates these principles while focusing on the interactions among urban and global systems; the roadmap can provide a blueprint for all stakeholders engaged in metropolitan areas to facilitate meaningful pathways to urban sustainability. The roadmap is organized in three phases: (1) creating the basis for a sustainability roadmap, (2) design and implementation, and (3) outcomes and reassessment (Figure S-1).

In the first phase, adopting urban sustainability principles, identifying opportunities and constraints, and prioritizing co-net benefits—activities that offer co-occurring, reasonably sized benefits while managing tradeoffs across the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of sustainability—form the basis for a sustainability roadmap. The second phase describes multiple and interchangeable steps for design and implementation of urban sustainability programs. These steps include engaging partnerships with major stakeholders and the public; establishing goals, targets, and indicators for traditional metropolitan concerns; developing strategies aimed at facilitating

greater urban sustainability; identifying data gaps to better analyze the dynamics and benchmarks of indicator frameworks; and implementation—focusing on the institutional scale(s) at which each issue can be addressed. The committee suggests that every indicator should be connected to both an implementation and impact statement to garner more support, to engage the public in the process, and to ensure the efficiency and impact of the indicator once realized. Outcomes and reassessment constitute the third phase of this roadmap, including assessing impacts from the local to the global scales, developing ground truthing and securing public buy-in, continuing the reassessment of priorities, and learning from outcomes.

Research needs on new frontiers in science and development that can further contribute to the pathways to urban sustainability include deeper understandings of urban metabolism, critical thresholds for indicators, different types of data, and decision-making processes linked across scales.

LESSONS FROM CITY PROFILES

In examining the various challenges and sustainability strategies in the nine profile cities, the study explored a wide range of issues and questions encompassing science, organization, communication, and governance. This set of cities illustrates challenges involving energy, natural resource management, climate adaptation, economic development, public health, social equity, community engagement, and land-use considerations. The individual context and situation of each city played a key role in the sustainability challenges and opportunity solutions each

faced. For example, New York and Los Angeles, the cities with the largest and most diverse populations, illustrated the longest history of implementing sustainability measures in addition to the largest reliance on imported resources and greatest challenges in reducing social inequities and eradicating poverty. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh provided examples of cities that actively pursued diversification of their economies with varied success and outcomes. Both implemented innovative collaborations with municipalities, nonprofits, and various public-private partnerships. Although Philadelphia and Pittsburgh capitalize on their economic assets, barriers in the form of policies at the state and national levels continue to hinder sustainable growth for these metropolitan regions. Chattanooga, Grand Rapids, Cedar Rapids, and Flint—all smaller in population size and density—have each pursued a different path to sustainability and met their intended goals with varying degrees of success. To provide a comparative snapshot of the nine cities assessed in the study, the spider charts (Figure 4-22) were created using the metrics data supplied in Tables 4-1, 4-3, 4-5, 4-7, 4-9, 4-11, 4-13, 4-15, and 4-17, with the convention being the larger the spider web, the more sustainable the city. These charts are not meant to provide a definitive determination as to whether a city qualifies as sustainable, but rather to provide an illustration as to how metropolitan areas varied as compared to the national average.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the review and synthesis of the information gathered during the course of this study, the committee has 10 recommendations for moving toward sustainable metropolitan regions. This set of recommendations targets the need for urban sustainability strategies to be multi-issue, multidimensional, integrative, and collaborative, acknowledging both the urgency and need to prioritize sustainability efforts, as well as the constraints of the global biophysical environment.

Global Constraints and Co-dependencies

First, an understanding of the extent to which local sustainability programs can contribute to global solutions is essential to putting local sustainability plans into a global context. This understanding begins with a comprehensive accounting of flows from source to city and vice versa.

- Recommendation 1: Actions in support of sustainability in one geographic area should not be taken at the expense of the sustainability of another. Cities should implement local sustainability plans and decision making that have a larger scope than the confines of the city or region.

Importance of Incorporating Cross-scale Processes

Sustainability planning efforts should address the multiple linkages among varying spatial scales relevant to particular sustainability processes.

- Recommendation 2: Urban leaders and planners should integrate sustainability policies and strategies across spatial and administrative scales, from block and neighborhood to city, region, state, and nation, to ensure the effectiveness of urban sustainability actions.

Cross-cutting Challenges, Solutions, and Co-benefits

Because the social, economic, and environmental dimensions of sustainability are interdependent and closely linked, pathways to urban sustainability must exploit synergies among the dimensions so as to yield co-benefits across the three dimensions.

- Recommendation 3: Urban leaders and planners should implement sustainability policies and programs that identify and establish processes for promoting synergies among environmental, economic, and social policies that produce co-benefits across more than one dimension of sustainability.

Shared Versus Unique Challenges

Each city combines uniqueness and generality in the sense that whereas no two cities are identical, many share some common traits and common problems, such as road congestion or high housing costs.

- Recommendation 4: Urban leaders and planners should look to cities with similar economic, environmental, social, and political contexts to understand and adapt local and regional sustainability strategies that have proven to provide measurable impact.

The Key Role of Science

Science plays a central role in illuminating pathways to urban sustainability. Sharing among cities requires building evidence of what actions have been taken in particular places and what were the associated outcomes. With this information, urban and regional planners can choose actions that have led to measurable progress toward sustainability goals in other places.

- Recommendation 5: Urban leaders and planners should gather scientific input to the maximum extent available in the form of metrics on social, health, environmental, and economic dimensions of sustainability; data related to policies, programs, and implementation processes; and measures of community involvement.

Partnerships for Sustainability

Partnerships and community engagement are essential to the success of sustainability efforts. In the cities examined, no sustainability initiative was undertaken without some form of collaboration or partnership, such as that between business leadership and local government or the extensive involvement of diverse groups of citizens.

- Recommendation 6: Cities should ensure broad stakeholder engagement in developing and implementing sustainability actions with all relevant constituencies, including nontraditional partners.

Durable and Dynamic Sustainability Planning

Moreover, the committee found that the durability of leadership and of sustainability planning is essential in facilitating the transition to greater sustainability. Enduring leadership structures will need to be written into cities’ operating budgets and sustainability plans and, where possible, voted into perpetuity by their citizens to ensure the ongoing success of sustainability efforts.

- Recommendation 7: Every city should develop a cohesive sustainability plan that acknowledges the unique characteristics of the city and its connections to global processes while supporting mechanisms for periodic updates to take account of significant changes in prevailing environmental, social, and economic conditions. Sustainability plans should strive to have measureable characteristics that enable tracking and assessment of progress, minimally along environmental, social, and economic lines.

Improving Opportunities, Outcomes, and Quality of Life for All

The committee also found that reducing inequality is an important yet often overlooked aspect of sustainability planning. Strategies aimed at reducing inequality are essential to improve quality of life not only for those with the fewest resources and opportunities, but also for the city’s entire population.

- Recommendation 8: Sustainability plans and actions should include policies to reduce inequality. It is critical that community members from across the economic, social, and institutional spectrum be included in identifying, designing, and implementing urban sustainability actions.

The Importance of Benchmarks and Thresholds

In addition, to measure progress toward sustainability, accurate data are essential to create sustainability metrics and indicators with benchmark targets and outcomes. Multiple rating systems exist for urban sustainability, but they are not common, cannot be shared, and differ in scale. Furthermore, many of these metrics and indicators have weak scientific underpinnings; additional research is needed to assess their relevance and applicability. Given these challenges, achieving a scientific consensus on effective metrics and indicators presents a grand challenge for future urban sustainability work.

- Recommendation 9: Cities should adopt comprehensive sustainability metrics that are firmly underpinned by research. These metrics should be connected to implementation, impact, and cost analyses to ensure efficiency, impact, and stakeholder engagement.

The Urgency in Sustainability

Finally, all three dimensions of sustainability hold serious challenges for urban, regional, and global sustainability, necessitating a call to action. Infrastructure replacement needs throughout the United States provide a window of opportunity for action by targeting designed strategies to address existing problems that have limited progress toward sustainability.

- Recommendation 10: Urban leaders and planners should be cognizant of the rapid pace of factors working against sustainability and should prioritize sustainability initiatives with an appropriate sense of urgency to yield significant progress toward urban sustainability.

As an increasing percentage of the world’s population and economic activities concentrate in urban areas, cities have become pivotal to discussions of sustainable development. While no single approach guarantees urban sustainability, it is valuable to assess the diversity of practices being implemented in urban and metropolitan regions to determine their transferability to other urban areas. Managing tradeoffs among the environmental, economic, and social dimensions of sustainability—while aiming to maximize total net benefits relative to costs—is an important part of the sustainability process. Because of the specificities of place and the particular problems being addressed, solutions are likely to be situation specific. Cross-place learning about how to manage such multidimensional problems will depend on developing and analyzing a data base that captures these specifics in many places and situations. Simultaneous action across multiple sectors and interconnected dimensions can facilitate cities’ transitions to sustainability. The sustainability principles and the roadmap described in this report can serve as a blueprint for academics, practitioners, policy makers, civil society, and other stakeholders seeking pathways to greater sustainability for metropolitan regions across the United States and globally.

This page intentionally left blank.