Review of the Research Program of the U.S. DRIVE Partnership: Fifth Report (2017)

Chapter: 4 Overall Assessment

4

Overall Assessment

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. DRIVE Partnership has matured significantly since its creation. Since the National Research Council (NRC) Phase 4 report (2013), several improvements in Partnership operation have been made, some of them at least in part in reaction to prior NRC review recommendations. Noteworthy among these improvements are the addition of associate members to the technical teams, enhanced engagement by the Executive Steering Group (although still inadequate), and development of the cradle-to-grave (C2G) analysis capability.

In this final chapter in prior reviews, a detailed analysis has been made of the budget allocated to various initiatives and the budget trends over time. Since the Partnership has repeatedly stressed that in fact it has no budget and is simply one of many inputs to the Department of Energy (DOE) process of budgeting and managing its own projects, this level of detail seems to be less appropriate in this fifth review of the Partnership. Individual chapters have attempted to show the DOE funding allocated to various projects within the purview of the Partnership, but it must be stressed that these are DOE expenditures and not Partnership expenditures.

The task of forming an overall assessment is also complicated by the situation described in Chapter 2, whereby the Partnership and the DOE had difficulty defining for the committee just exactly what is included within the Partnership vis-à-vis the DOE portfolio of projects. Nevertheless, the committee has attempted in this Phase 5 report to review the appropriateness of, and progress on all of, the projects designated by the Partnership in which it is engaged, whether these precisely align with the DOE portfolio or not.

MAJOR ACHIEVEMENTS, PROGRESS, AND BARRIERS

Given that the Partnership exists primarily as a technical information exchange and serves as just one of the many inputs to DOE programs, where the budgets for all of this activity reside, it is difficult to ascertain exactly which achievements are directly attributable to the Partnership. The Partnership points to the DOE Annual Merit Review for details on all of its initiatives, where there is a wealth of valuable information.

Nevertheless, the individual chapters have documented achievements and barriers relating to their specific focus areas. Progress has clearly been made in such areas as advanced combustion, hydrogen fuel cell durability and cost, and electric drive systems (motor, power electronics, and battery) cost. At the same time, market introduction of improved hybrid electric vehicles and battery electric vehicles (BEVs) by automotive manufacturers represented in U.S. DRIVE and others, indicates that much of this technology is migrating out of the precompetitive realm and into the competitive marketplace. The hydrogen fuel cell vehicle (HFCV), currently being introduced in limited numbers by foreign original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), and expected by 2020 by one U.S. OEM (GM1), is expected to follow a path to commercialization with its own unique challenges, including, for example, infrastructure development. Since the Partnership is exclusively dedicated to precompetitive research and development, it is important that, informed by the C2G analysis, the portfolio be regularly reviewed to ensure that the focus remains on precompetitive challenges and relevant technology enablers. Some specific examples of areas where this critical review should take place are given in Chapter 3.

While some of the remaining challenges are purely technical, cost remains a formidable barrier for essentially all the technologies under development. The other notable barrier is the infrastructure challenge confronting hydrogen. Policy matters and deployment are by definition beyond the scope of the Partnership, but lack of infrastructure is arguably the biggest challenge to the widespread deployment of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, and continued emphasis by DOE on infrastructure enablers as well as an implementation plan is vital, whether within the Partnership or not.

ADEQUACY, BALANCE, AND FUNDING

Historically, in the transition from the predecessor Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles program into the FreedomCAR and Fuel Partnership, hydrogen-related activities represented roughly 70 percent of the relevant DOE budget, and non-hydrogen-related efforts consumed the remaining 30 percent. Coincident with the NRC (2010) Phase 3 report, a significant shift in this bal-

___________________

1 See, for example, R. Truett, “Fuel Cell Puzzle Comes Together,” Automotive News, October 11, 2016, http://www.autonews.com/article/20161011/BLOG06/310119999/fuel-cell-puzzle-comes-together.

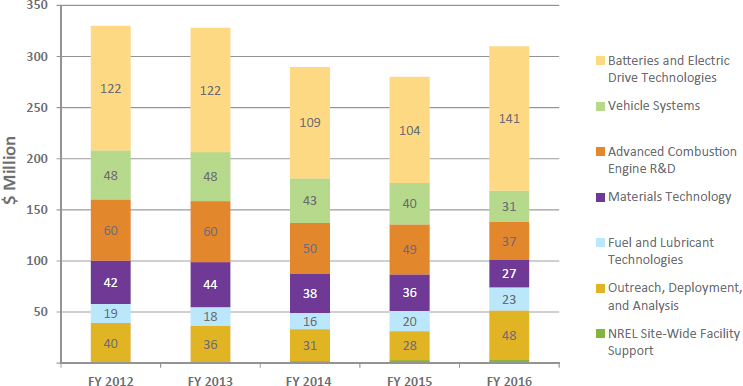

ance took place and the hydrogen-related share dropped to roughly 30 percent. Having dropped by around 50 percent, the DOE budget devoted to hydrogen and fuel cells-related activities, which include both stationary and automotive applications, has since remained stable at around $100 million per year, while the budget devoted to non-hydrogen-related vehicle technology has gradually increased. For fiscal year 2016, hydrogen and fuel cell-related work is $101 million per year and the Vehicle Technologies Office funding is $310 million per year.

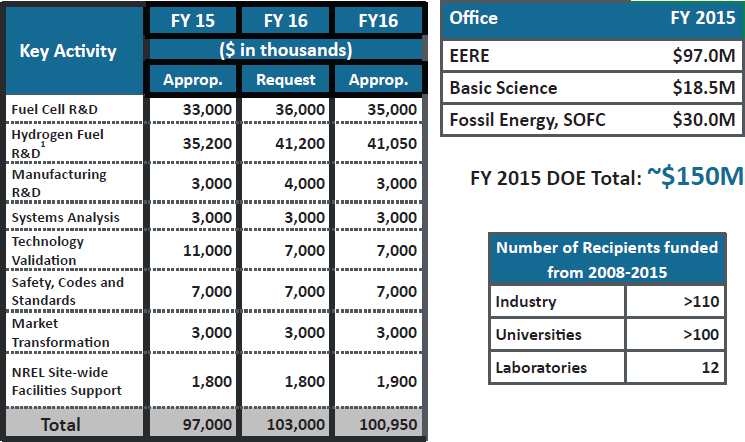

Much of the large shift in funding to vehicle technologies was in electric vehicles, especially batteries. Since fuel cell vehicles are inherently electric vehicles, much of the work on electric drivetrain and improved batteries is equally applicable to both plug-in electric vehicles (both BEVs and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles) and HFCVs, and while the $100 million devoted to purely hydrogen and fuel cell technologies is a much smaller share of the total DOE Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) budget, it is still felt by the committee to be appropriate as a share of the overall effort for projects supporting U.S. DRIVE targets and goals. Within that overall effort, priorities for funding may shift among technical areas as technical challenges change. Furthermore, as noted in Figure 4-1, there is hydrogen-related work in the DOE’s Office of Basic Energy Sciences and Office of Fossil Energy, offices outside EERE, as well as the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, which raised the overall total to approximately $150 million in FY 2015. (Similarly, there is work being done on batteries and electric drives within DOE but outside EERE.)

The respective DOE hydrogen/fuel cells and vehicle technologies budgets for fiscal year 2016 are shown in Figures 4-1 and 4-2, provided by DOE on February 3, 2016.

Finding 4-1. The share of Partnership-related DOE funding devoted to hydrogen/fuel cells has remained essentially stable at 25 to 30 percent since 2010 (having dropped from approximately 70 percent of total funding in earlier years) and is judged by the committee as appropriate, although within that overall effort, priorities for funding may shift among technical areas as technical challenges change.

CROSSCUTTING ISSUES

Since the Partnership is just one of many inputs to the DOE, and can offer only guidance and advice, the burden falls on the DOE leadership, assisted by the enhanced C2G analysis capability, to perform urgently needed in-depth portfolio analysis in two critical areas:

- Review and, as appropriate, terminate those projects on technologies that no longer offer any realistic chance of meeting the objectives, and move related DOE funding to higher potential candidates. Several examples are cited throughout this report.

SOURCE: Satyapal (2016).

SOURCE: Howell (2016).

- Drawing on advice from the technical teams, terminate activities that are crossing over into the competitive domain and shift the focus and funding to precompetitive technology enablers. While this analysis is urgent, it is anticipated that the resulting transition in activities will necessarily be gradual.

STRATEGIC ISSUES LOOKING FORWARD

Three trends, which could have strategic implications for the future, have emerged since the NRC Phase 4 review of the Partnership took place:

- The dramatic change in domestic energy production has rendered the Obama administration’s objective of reducing oil imports by 50 percent almost moot. While criteria pollutants will always be a concern and require substantial technical development to mitigate, it seems likely that in the future greenhouse gas (GHG) goals will present the greatest challenge. With GHG emissions as a primary focus, the pathways (e.g., combinations of vehicle technologies and fuels) to achieve the extremely aggressive goals are very limited and would suggest that Partnership-related projects be increasingly focused on those few pathways that offer a realistic chance of success in meeting those goals.

- With numerous electric vehicles (HFCVs and BEVs) expected to enter the marketplace in the next few years, the consumer will be presented with a number of zero-emission vehicle options to select from. This transition can be expected to take many years, and infrastructure challenges are among the greatest challenges in each case, but particularly with regard to hydrogen. Although deployment and infrastructure are beyond the scope of the Partnership, there remains a need for precompetitive work on technology enablers to reduce system cost, improve durability, and substantially lower the cost of delivered “green” hydrogen at scale and electricity.

- As discussed in Chapter 1 (see the section “Trends in Vehicle Automation and Smart Transportation”), the precise impact on the U.S. DRIVE Partnership is unclear at this point, but there is no doubt that the move toward connected and autonomous vehicles is dramatically accelerating. Somewhat related to this is the increasingly rapid proliferation of such personal mobility models as car-sharing and ride-sharing. While there does not appear to be an obvious connection between these trends and the current Partnership-related DOE portfolio, shared, autonomous, plug-in electric vehicles could contribute to the environmental and energy goals of U.S. DRIVE, and they deserve close scrutiny for their potential impact on the Partnership in the future.

Finding 4-2. Significant changes are occurring in the U.S. energy supply and demand situation, in the automotive sector as alternative propulsion system vehicles enter the marketplace, and in options for personal mobility, since the National Research Council Phase 4 review in 2012-2013.

Recommendation 4-1. The Executive Steering Group should identify appropriate changes in Partnership focus to reflect the impact of new personal mobility models, shrinking opportunities to achieve the aggressive greenhouse gas goals, the transition of many candidate technologies into the competitive domain, and the significant infrastructure challenges in providing hydrogen at fueling stations at a competitive cost—in particular, while retaining the focus on precompetitive technology enablers.

REFERENCES

Howell, D. 2016. “DOE/EERE Vehicle Technologies Office Overview.” Presentation to the Committee on the Review of the Research Program of the U.S. DRIVE Partnership, Phase 5, Washington, D.C., February 3.

NRC (National Research Council). 2010. Review of the Research Program of the FreedomCAR and Fuel Partnership, Third Report. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

NRC. 2013. Review of the Research Program of the U.S. DRIVE Partnership, Fourth Report. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Satyapal, S. 2016. “Program Update for the National Research Council Review.” Presentation to the Committee on the Review of the Research Program of the U.S. DRIVE Partnership, Phase 5, Washington, D.C., February 3.