Making Medicines Affordable: A National Imperative (2018)

Chapter: Appendix A: A Dissenting View - Michael Rosenblatt and Henri Termeer

A

A Dissenting View

Michael Rosenblatt and Henri Termeer1

We are grateful for the contributions of our colleagues on this committee. We had hoped that the committee, after so much analysis and deliberation, would arrive at a consensus. Instead, we find the need for us to prepare this dissenting view. Our hope is that our view offers an alternative and effective set of recommendations that are sufficient to achieve the objectives of the committee. We believe that the committee’s recommendations, if actually implemented, will lead to unintended consequences that will damage the health of people in the United States and damage the health of an industry whose innovations are essential to addressing unmet medical needs in the future. Our dissenting perspective

___________________

1 Henri Termeer passed away during the advanced stages of this report’s development. This dissent, therefore, reflects the draft at the time of Termeer’s death. Only editorial changes, without any change to the core arguments, were made by Michael Rosenblatt. The main text of this report underwent further revisions in response to review, but Rosenblatt made the decision not to further revise this dissenting viewpoint in order to retain the original spirit and authentic co-authorship of this piece. Termeer and Rosenblatt emphasized that they wrote this piece not with the intent of solely presenting an “industry perspective.” Rather, their intention was to provide a balanced view derived from insights and experiences in more than one sector, and to reflect their shared commitment to always place patients first.

Portions of this dissent are drawn from two publications by the authors:

Rosenblatt, M. 2014. The real cost of high-priced drugs. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/11/the-real-cost-of-high-priced-drugs (accessed November 13, 2017).

Rosenblatt, M., and H. Termeer. 2017. Reframing the conversation on drug pricing. NEJM Catalyst. https://catalyst.nejm.org/reframing-conversation-drug-pricing (accessed November 13, 2017).

provides: (1) background on why the biopharmaceutical industry is important to the health of Americans and our economy, (2) proposed principles to guide the generation of an effective set of recommendations, (3) specific recommendations that replace some present in the current draft, and (4) comments on the potential impact of implementing the recommendations.

THE SOCIETAL IMPACT OF BIOPHARMACEUTICALS

The introduction of the first antibiotics—sulfanilamide, streptomycin, and penicillin—launched the modern era in biopharmaceutical therapies. These early “miracle drugs” began saving lives from the instant of their availability. For penicillin, which was discovered in the United Kingdom, production at a scale of billions of units was achieved by a consortium of 20 pharmaceutical companies as part of the effort of the Allies to achieve victory in World War II.

Since then, a range of different medicines and vaccines has transformed health and society. Diseases with public health dimensions, such as hypertension, lipid disorders, diabetes, and osteoporosis, now have foundational (although imperfect) treatments. In recent years, previously neglected rare diseases that afflict only small numbers of people (but which have large impacts on individuals and their families) have been benefitting from innovative therapies.

AIDS was a major epidemic in the 1990s, filling one-quarter of the beds in some hospitals. The AIDS diagnosis was considered worse than a diagnosis of cancer because AIDS was universally fatal. The human loss was catastrophic. The financial burden was crushing: unabated, AIDS was projected to bankrupt the health system. But within a decade of researchers identifying the virus that caused the disease, new medicines had been developed that stopped the epidemic in its tracks. Today, AIDS has essentially been transformed into a chronic disease with a near-normal life expectancy. It is hard to picture our society if the AIDS epidemic were still continuing today.

It is important to note that the key AIDS therapies originated from the U.S. biopharmaceutical industry. The only reason that a rapid and effective response could be made was the existence of an innovation infrastructure in the United States, which meant that AIDS research did not need to start from scratch. Universities and industry were well positioned to translate scientific insights into new therapies from the moment they were made. A critically important lesson that emerged is that we must not damage this innovation infrastructure; without it, finding a treatment or cure for Alzheimer’s and other diseases is hopeless.

Among the most dramatic advances in recent decades have been the development of drugs that cure some childhood and adult cancers, the development of drugs that cure hepatitis C, and the development of vaccines

that prevent hepatitis B. The recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine publications A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C (2017) and Eliminating the Public Health Problem of Hepatitis B and C in the United States (2016) put forward a plan to eliminate these two diseases by 2030. The reason that this plan is realistic is the ability of this country’s innovation infrastructure to come up with a steady stream of inventions, and this in turn is made by possible by the existence of various incentives.

The impact of vaccines on health has been enormous: Deaths from viruses have been prevented for millions of children globally. The polio epidemic was ended, and vaccines that prevent cancer have been created (cervical cancer via immunization against human papilloma virus strains). In the United States, it is virtually impossible to find a single individual whose personal health or that of a loved one has not benefitted from a medicine or vaccine.

This is the richest period in history for the sciences that are fundamental to medicine. We are well positioned—thanks to our universities, hospitals, and industry (and the interactions among them)—to generate insights and discoveries. Furthermore, we are experienced in translating these insights and discoveries into innovations that truly benefit health. But the scientific enterprise is fragmented and highly vulnerable to a decline in investment in any of the interacting sectors.

In truth, biopharmaceutical research and development is just beginning to take advantage of the explosion of knowledge in science. Unfortunately for patients living today with diseases for which there is no treatment, the era of modern medicine has yet to begin.

WHERE DO OUR MEDICINES COME FROM?

The pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries use insights from research conducted by researchers in universities, government, and other private enterprises to develop new medicines. Inventing a new drug is the longest, most expensive, most regulated, and most risky undertaking of any product-development process in any industry. Nine out of 10 drug candidates that enter clinical trials fail, and only 2 out of 10 recover the cost of capital. Nevertheless, industry in the United States continues to reinvest approximately 10 to 20 percent of its revenues in research and development. This amount outpaces the National Institutes of Health (NIH) research budget by nearly two to one. Even for those familiar with other research-based industries, it is difficult to appreciate just how challenging it is to create a new drug and how real the odds are of failure.

Many point to the reliance of industry on NIH and other government-sponsored basic research. The process of inventing drugs starts with fun-

damental insights, usually obtained in universities and research institutes. Industry relies on these insights, but these discoveries are a long way from actually inventing a drug. Industry supports government-sponsored research through the payment of taxes and the licensing fees it pays for patents (generated through government-funded research) held by universities. It is also worth noting that public funding of basic research likely would not be at its current levels but for the promise that such research will lead to new therapies for the U.S. population.

The biopharmaceutical industry is critically important to improving and maintaining public health and is essential for a future with less disease. The United States is the “medicine chest” for the world. Two-thirds of new drugs in the past decade and more than 80 percent of the drugs in the world’s biopharmaceutical pipeline today emerge from the United States. The biopharmaceutical industry is one of the few sectors of the national economy that has a favorable balance of trade.

Drug discovery and development is not like going to the moon. It is not an engineering problem that can be solved by assembling a team of capable engineers and providing sufficient resources. Rather, creating a drug is a problem completely subject to human biology with all its intrinsic complexity, variability, and unpredictability. Drugs work by introducing an agent that perturbs in a favorable direction a physiological process that has taken a wrong turn. Confounding such interventions are the interlocking systems of human biology. The challenge is to favorably perturb the selected pathway without distorting others. If drug invention were simply an engineering problem, then by now we would have a vaccine for AIDS (35 years after the beginning of the outbreak) and a cure for Alzheimer’s disease.

New medicines and vaccines are generated and enter clinical practice by a process that is far from perfect but which is not fundamentally broken. Despite its complexity and unpredictability, the current system generates a flow of medicines to address unmet medical needs—the U.S. biomedical enterprise understands the process and it works.

ROLE OF INNOVATION

“Innovation” is an overused term. There is no doubt that innovation is needed in every component of health care: hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes, among others. Most innovations are aimed at improving efficiency while enhancing the quality of medical care. Drugs and vaccines, however, are fundamentally different: they are inventions that we can touch and feel. Society faces an imminent tsunami of health care costs from Alzheimer’s and other mental diseases. Among the baby boomer generation, one in nine people will develop Alzheimer’s. There are currently 47 million people living with dementia worldwide, a number projected to double every 20

years. Today’s $200 billion annual U.S. expenditure on Alzheimer’s will balloon to $1 trillion by 2050, siphoning resources from education, social welfare, defense, roads, and other vital areas. Does anyone seriously believe that the impending crisis can be averted by building more efficient hospitals, better health care delivery systems and nursing homes, and higher-quality home care?

The Alzheimer’s example illustrates that it is the cost of disease that is expensive. Health care costs are escalating because we are unable to treat or cure so many diseases. Society has only one possible solution: new drugs that change the course of Alzheimer’s by arresting, delaying, or preventing the disease. But the record of failure, despite billions of dollars invested, illustrates the need for continued incentives to assume high risk and drive invention: in more than 400 clinical trials of more than 35 agents intended to treat Alzheimer’s in the past decade, the failure rate was more than 99 percent. Only 7 percent of the clinical trials have been government-funded; industry has spent $100 billion on Alzheimer’s research and development.

During the several-month period in which the committee deliberated, two promising Alzheimer’s drugs (from Eli Lilly and Merck & Co., Inc.) experienced major setbacks in clinical trials—setbacks that came after one to two decades of research investment. Given the track record, it is reasonable to ask: who would gamble their own time and money on inventing the next agent without adequate incentives? Yet, Alzheimer’s research and development programs continue to receive industry investment. Despite the high-profile setbacks, there has been learning. And with each iteration, the chances of success increase. The extraordinary costs of failure across therapeutic areas must be included when computing the investment needed to generate a successful drug. Even more expensive for society is the cost of doing nothing, and doing nothing would be a moral failing.

Clearly, an effective prevention, treatment, or even cure for Alzheimer’s disease would be of great value to patients, their families, and society. But what if we tried to place a price tag on such an agent today? Given the extraordinary cumulative investment already made and now continuing and the risk involved, capping a price today would inhibit future investment. Such an approach also fails to recognize that while the initial price of an Alzheimer’s drug might be high, the price will come down dramatically with time (initially from competition and later from generics, as discussed next)—no legislation is needed. It is incentives that are needed to stimulate continued investment. Alzheimer’s disease is but one example. We are not at the end of drug discovery; we are just at the beginning. We need new medicines for cancer, cardiovascular diseases, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, and more rare and neglected diseases.

THE ROLE OF PATENTS

This report describes patents as “legal monopolies.”2 The implication is that patent law permits something that otherwise is illegal. And the sense of the report is that the patent mechanism has somehow been co-opted inappropriately by the biopharmaceutical industry. Patents and the protection of intellectual property are the foundation of the modern U.S. economy. Edison obtained patents for electricity and light bulbs—there is a reason that so many utilities have “Edison” in their name. Similarly, we would not have telephones and telephone companies called “Bell” but for patents. The list continues to today and includes computers, iPhones, etc. Patents indeed provide for exclusivity or a “monopoly” for a single biopharmaceutical product, but not for a whole class of therapeutic agents. A reason that drug prices generally fall over time is that patents are narrow enough that other, often closely similar products, can enter the same arena and compete. The competing products are themselves patented. In the U.S. economy, it is straightforward: without patents, there would be no investment; without investment, there will not be any innovation. It is important to remember that patents do not obligate the patent holder to maintain exclusivity. The patents for AIDS drugs were placed in a “patent bank” to enable companies to access them for production for patients in the developing world.

WHAT IS THE PRICE OF A DRUG?

In the United States, even with the recent introduction of expensive cancer and hepatitis C drugs, prescription drugs account for 10 to 15 percent of the total cost of health care, a figure that has been constant over the past 50 years. The prices of drugs in different therapeutic categories rise and fall over time. Yesterday, AIDS drugs were receiving attention; today it is cancer. Tomorrow, it will be a different disease. But the average across categories remains remarkably stable. To provide one example for comparison purposes, the worldwide revenues from one of the new immune oncology drugs, pembrolizumab (Keytruda)—whose list price is approximately $150,000 for a full course of treatment—were $1.4 billion in 2016. In comparison, the revenues of just one cancer hospital in the United States, Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York, was $3.6 billion.

Most of the current discussion on drug prices focuses selectively on the list price of a drug on the day of its introduction into the market. The

___________________

2 As noted in the previous footnote of this appendix, some mismatches remain between the current content of the main report and this response. This is because the main report underwent several rounds of revisions after the dissent was completed. Rather than having one author continue to respond to new revisions, the integrity of the co-authorship of the dissenting statement was maintained. This section on patents is an example of these mismatches.

discussion narrowly revolves around immediate cost to the system. In order to make informed analysis and recommendations, however, we need to expand the boundaries of the pricing discussion in several dimensions: long term versus short term, value versus cost (not list price), and global versus only the United States.

A discussion on pricing needs to begin with the question: What is the price of a medicine? There is no simple answer. Prices for the same drug vary within different sectors of health care in the United States, across regions of the globe, and over time. The launch price falls dramatically with patent expiration. But usually there is also competition along the way that produces large intermediate declines in price. The current debate on drug pricing does not take these built-in substantial falls in price into account; instead it focuses exclusively on a drug’s price on day 1. For most new drugs, the patent expires approximately 10 to 12 years after market introduction. At that time, the price generally falls to pennies on the dollar.

Atorvastatin (Lipitor), a leading statin for treating elevated cholesterol, was introduced at more than $5 per tablet. When it became generic, the price fell by 95 percent to 31 cents per tablet. Many prescriptions for a statin in the United States are for generic atorvastatin, a situation likely to continue for the foreseeable future. Alendronate (Fosamax) for osteoporosis was $2.60 daily, but is now 28 cents. These low prices will persist in perpetuity. So what is the accurate cost of these medicines to society—the price on day 1, or the price over decades?

This report states that the value of medicines cannot be calculated at this time because we lack the tools. It is true that “all in” value or savings cannot be readily or accurately determined fully. But there are approximations that are worthy of attention and provide guidance. The U.S. Congressional Budget Office demonstrated that a 1 percent increase in spending on prescriptions yields a 0.2 percent decrease in expense across the much larger base of medical services. This translates to roughly a two-fold return for every dollar spent on drugs, validating the notion that medicines save lives and money.

Informed by these views, it is time to look at medicines not in isolation as a single piece of the health care puzzle, but rather as part of an interlocking system with the patient at its center.

THE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF THE BIOPHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY

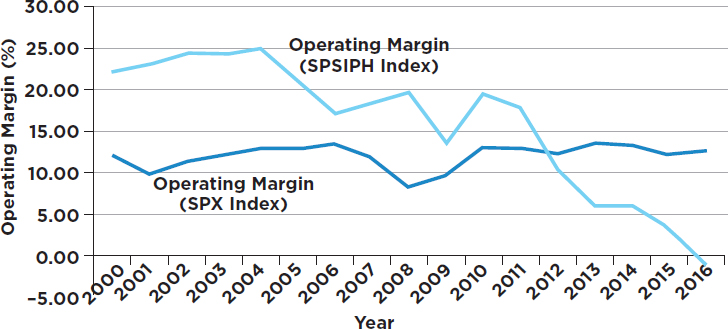

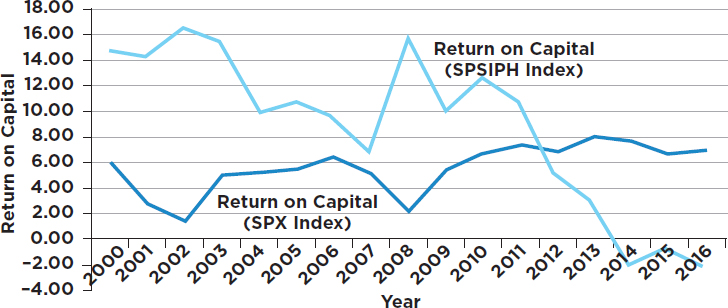

During our deliberations, the committee sought information on the financial performance of the biopharmaceutical industry. Graphs depicting performance over the most recent 16-year period (with comparison to a cross-section of all U.S. industry) were obtained and included in an earlier

draft of the report.3 The data, shown below, reveal that the biopharmaceutical industry, on average, performed better than the average of aggregated U.S. industries from 2000 to 2011. But for the past 5 to 6 years, the operating margins and return on capital for the biopharmaceutical industry were considerably worse than the broad industrial average (see Figures A-1 and A-2). This important information, with implications about the potential impact of acutely changing the research-driven biopharmaceutical business model, was not included in the subsequent draft to which this dissenting view responds.

Some will point out that there are companies in the biopharmaceutical sector that perform well above average. That is true. But there are also companies that perform well below average; that’s the reason average performance is calculated.

PRINCIPLES AND FINDINGS

This committee was tasked with “ensuring patient access to affordable medicines.” Each word in this task is essential. In our view, carrying out recommendations that move money around the complex web of health care or that create revenues or savings for one component without reducing costs to patients would be a futile exercise. The high cost of drugs experienced by patients is not simply and solely the result of biopharmaceutical industry pricing. Pharmacy benefit management (PBM) companies and other intermediaries in the supply chain contribute to patient “out-of-pocket” costs and limit access, as does the unique and idiosyncratic structure of health insurance (both government and private). Unless the interlocking dynamics of this complex system are probed by modeling or pilot programs, the recommendations contained in this report will likely create unintended consequences with long-term impacts on public health.

We note that the report uses the terms “consumer” and “patient” interchangeably. In our view, there is an important difference. Consumers have discretion. In a market, they can choose to buy one product or another or forgo altogether making a purchase. Patients are not in so fortunate a position; patients are financially exposed and vulnerable in a way that is quite

___________________

3 The committee compared the aggregate 16-year trend of selected market parameters (price earnings ratio, gross margin, operating margin, return on capital, basic earnings per share, and the earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization [EBITDA]) from 2000 to 2016 for the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 index and the S&P Pharmaceuticals Select Industry Index. The S&P 500 is widely regarded as the most meaningful single gauge of large-cap U.S. equities and includes 500 leading companies that capture approximately 80 percent of market capitalization. The S&P Pharmaceuticals Select Industry Index comprises stocks in the S&P Total Market Index that are classified in the standard pharmaceuticals sub-industry of the global industry classification. This former index contains 38 companies.

different than a typical consumer. They have a disease that almost always requires that they purchase or copay for a medicine. And the doctor, not the patient, via a prescription determines which product the patient must use (unless a generic version is available). So we, instead, focus our contribution on “patients” and their experience obtaining medicines through insurance and intermediaries.

Making policy recommendations based on the introductory price of drugs fails to recognize the changes in price that occur for virtually all drugs over time. Looking exclusively at the price of a drug on day 1 is viewing reality through a distorted lens. Usually within 12 to 18 months after market entry, competition is introduced and prices fall considerably. (For example, the cost of hepatitis C drugs fell 40 to 60 percent when the first competitor entered the market.) After 10 to 12 years, when a patent expires, the price falls by 95 percent (or more) as generics enter the market. No other component of health care falls so dramatically, not hospital or physician fees. With patent expiry and the switch to generic, society inherits a kind of “annuity”: a valuable drug that remains very low-priced for the remainder of its useful life.

We also note that not every patient with a disease needs to be started on a new medicine as soon as it is available. It should be possible to plan the introduction of a medicine into clinical use. Planning to eliminate hepatitis B and C—as called for by the National Academies reports noted earlier—by 2030 is ambitious, but feasible. Planning for elimination by 2020 is not, for both logistical and market reasons. And allowing some time for competition to enter will naturally address some of the financial challenges.

OUR OBSERVATIONS AND SUGGESTED GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR RECOMMENDATIONS

- We should remember that every component of the U.S. health care system is more expensive—often by a factor of three to five—than health care systems elsewhere in the developed world. Even dramatic reductions in the cost of medicines will not alone fix the high cost of health care in the United States. A magic wand that made all prescription drugs free of charge would still leave the United States with the most expensive health care system in the world by a wide margin.

- Out-of-pocket expenses for health care for people in the United States, even those with insurance, are too large, often ruinously so. The notion that forcing patients to have “skin in the game” for prescription drugs will lead to better outcomes and less health expenditure is controversial at best and has been proven incorrect for some common chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes). Any policy

-

recommendation in this area should connect the dots between the proposed intervention and financial relief to patients.

- Given the current structure of insurance, with its premiums, deductibles, and copays, even dramatic reductions in drug prices will translate into little financial relief for patients.

- Research and development is crucially important. It is essential that policy recommendations not sacrifice the future translation of medical advances into new therapies. As a matter of principle, recommendations should either stimulate investments in research and development or be neutral. Given the long-term investment required to invent a drug or vaccine, policies also need to provide stability. Inhibiting investments in research and development would be a mistake with long-term consequences.

- Recommendations should be modeled before they are made, and pilot programs should be run before full implementation. We cannot afford to make casual recommendations about an ecosystem and industry of critical importance to society.

- PBMs, 340B hospitals and clinics, and other intermediaries operate with large margins often based on perverse incentives. Little of the savings extracted from manufacturers’ discounts and rebates to PBMs are passed on to patients. And those patients least able to afford medicines, namely the uninsured, pay the highest (list) prices.

- Insurance in the United States is a misnomer; we operate a “cost-sharing” system in which patients directly carry much of the financial burden. Compared with the health insurance provided in virtually every other country in the developed world, our insurance coverage falls short, especially for prescription drugs, and it seems likely that in the future even more expense will be shifted to patients via deductibles and copays.

- Branded drugs have a limited time on the market as unique products. Competition drives down the cost of drugs, as does the expiration of patent protection. The research and development–driven biopharmaceutical industry is fundamentally different from the generic drug industry. By analogy, those who design new cars are fundamentally different from those who manufacture “after market” replacement parts. The generic industry fulfills 90 percent of drug prescriptions in the United States. Accordingly, it should receive its own set of specific recommendations. The same is true for biosimilars.

- There has been bad behavior in both the research and development–driven and generic industry. There have been many yearly and semi-yearly double-digit price increases for branded drugs. Neither

- The impact of recommendations needs to be assessed not only individually but also in aggregate. Recommendations that might appear individually to have moderate effects can collectively overshoot the mark. Taken together, the biopharmaceutical sector is not unusually profitable (as can be seen in Figures A-1 and A-2).

price abuse of old drugs with unique market positions nor price abuse of generic drugs should not be tolerated.

SOURCE: Data retrieved from Bloomberg Terminal .NetFrameworkV4 (March 2017).

SOURCE: Data retrieved from Bloomberg Terminal .NetFrameworkV4 (March 2017).

-

Removing too much margin will affect its ability to invest. A collection of recommendations that reduce research and development investment by the pharmaceutical, biotech, and venture capital industries should not be made.

- Ascribing motives and making presumptions and generalizations about the values of an entire industry should not be part of any serious policy recommendations. Veiled threats of future actions, which likely would never be used by the U.S. government, are not helpful in the context of an already intense debate. Advocacy for cooperation and collaboration is likely to be more productive when making recommendations that will require sacrifice across many components of the health care sector.

RECOMMENDED ACTIONS IN THIS REPORT AND OUR ASSESSMENT

- Transparency is needed at a level that is sufficient—but no more than sufficient—to influence the market forces on key components of the supply chain. The committee has a recommendation calling for publicizing the details provided about relevant financial transactions that go beyond the basic information that is needed and that should be made available. The big three PBMs control approximately 80 percent of prescriptions in the United States and enjoy large margins in their business. They now receive approximately 40 percent of the revenues of the total payment for drugs. Their research and development investment and risk over time do not compare with that of the biopharmaceutical industry, yet they enjoy almost half the revenue from the sale of prescription drugs. Furthermore, they have perverse incentives: the higher the price of the drug, the more profit they make.

The report fails to realize the large opportunity to reduce drug costs that would result from changes in the U.S. system of PBMs. There is no reason to pay for distribution of a drug based on a percentage of its price. Imagine if one paid FedEx, UPS, or the U.S. Postal Service for delivery of an item based on the value of the package rather than a flat fee. Consider the savings to society if Amazon started a prescription drug delivery business (which might happen). The lack of transparency of PBMs and the nature of their business model permeates almost all aspects of the cost of drugs in the United States. For example, when Mylan raised the price of an EpiPen (generic epinephrine) to $600 per device, there was deserved public outrage. But how many people understood that $300 of the $600 went to PBMs like Express Scripts?

Assessment: Potentially, this represents the largest opportunity among the committee’s recommended actions. Transparency would help bring the margins of PBMs and 340B hospital and clinic plans toward a range that is more commensurate with the value they deliver. It might also lower prices from the biopharmaceutical companies. And transparency likely will reduce bad behavior and abuse in the market. Participants in the markets will perform better. If properly structured, this would pass savings on to patients. Importantly, it would not inhibit investments in research and development.

- Medicare should have the right to negotiate purchase prices of medicines. In reality, prices are already negotiated for a large portion of Medicare Part D through the private insurance companies that provide coverage under Part D to patients.

Assessment: This recommended change alone will create a great change in the dynamics of the market compared with the current situation. Combined with transparency, this recommended action will go a long way toward reducing drug costs; in fact, these two recommended actions alone may prove sufficient to achieve the objectives regarding the cost of medicines. Other government buyers, such as the Veterans Health Administration and Medicaid, should continue to be able to negotiate. This new environment would mirror the private market, which has multiple buyers, each of which negotiates independently. However, allowing all government health plans to negotiate as a single block would establish a near monopoly that would translate into functional price controls. This, in turn, would be likely to have a devastating effect on long-term, high-risk investment.

- The generic drug industry needs both promotion and further regulation. It has worked exceedingly well at bringing less expensive, but quality-controlled drugs to the United States. However, some monopoly situations have occurred and have been abused. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration should be strengthened to enable more rapid entry (and reduce the backlog) of safe generics into the U.S. market—a good thing for generic companies. The same is true for biosimilars. Generic companies enjoy special legal protection. Given these circumstances, it is reasonable to require generic companies to provide notice (e.g., 1 to 2 years) before terminating the availability of a drug.

Assessment: A stable supply of generic drugs will be available. Monopoly situations and abuse will be diminished. And the incentive for research and development–driven companies to replace products lost to patent expiration will persist or even be intensified.

- Sickness strikes rich and poor alike. The U.S. insurance system provides only partial coverage and places an inordinate financial burden on the poorest in society. Public and private insurance plans need to be revised and coverage improved. The ongoing shift of drug costs to patients’ out-of-pocket expenses must stop. “Doughnut holes” and “tiered pricing” are totally disconnected from good medical practice—they are pure economic constructs and are not oriented to improving health (for many people, they do the opposite). Some of the recommended actions in the report are modeled on the National Health Service of the United Kingdom. People in the United States envy the lower drug prices there. But people of the United Kingdom are often the last or one among the last in Europe to have access to a new drug. For the U.K. subpopulation with cancer, life expectancy is 2 to 4 years shorter than in the United States. Importantly, in national health systems like those in the United Kingdom and other European countries, medicines are provided to patients with no out-of-pocket expense. Access to medicines is severely restricted by the financial burden borne by patients. Patient access would improve dramatically if the financial obligation for patients were truly limited.

Assessment: This is a large opportunity to increase access, improve health, and simultaneously drive innovation. Patient access to affordable medicines will increase. Currently, out-of-pocket cost is a major factor in nonadherence to prescriptions. Non-adherence has been documented to result in poorer health outcomes. With more patients covered, adherence and health will go up. And with increased insurance coverage, industry will have greater incentives to discover drugs for unmet medical needs.

- Efforts should be made to level the playing field for drug pricing in the developed world. Currently, the United States bears a disproportionate burden for the cost of drugs and the support of innovation, while Europe and other regions do not pay a fair share.

Assessment: Drug prices in the United States might stabilize; European prices would increase. And the biopharmaceutical industry in the United States would be better able to provide drugs at or below cost to the poorer regions of the world.

- The Orphan Drug Act should be revised, but not exactly in the complicated way recommended by the committee in this report. The act has been very successful in spurring the invention of drugs for rare diseases, but has also created some unintended conse-

quences. The major problems can be readily addressed just by lowering the current requirement to a number lower than 200,000 afflicted patients. An analysis needs to be performed to select the correct number based on medical knowledge and epidemiology, not just economics. This is especially important as we enter the era of precision medicine where new subpopulations of people within a disease category will be identified.

Assessment: Orphan drug designation confers special privilege in the marketplace in terms of exclusivity and opportunity for high prices. Now that the legislation has been in place for more than 30 years, it appears that the limit of 200,000 patients may be too generous and may dilute the intended impact. A lower number would be more in line with the original intent, stimulating initiatives to find drugs for those with rare diseases while enabling market forces to influence price on more new drugs than in the past.

- Each action recommended in this report needs to be modeled for benefits, trade-offs, and potential unintended consequences. Furthermore, for many recommended actions, pilot programs should be tested after modeling and prior to implementation. Along the same lines, modeling of the impact of the aggregated recommendations needs to be performed.

Assessment:

- Recommendations that provide financial relief to patients will receive top priority.

- The additive or potential synergistic impact of the set of recommendations taken together will be understood.

- Innovation is fragile and too important to diminish or curtail. Modeling and piloting will lessen the chances of unforeseen outcomes.

RECOMMENDED ACTIONS WE CANNOT ENDORSE

We list actions recommended in this report that we cannot support and provide our rationale for opposing them. We doubt that these actions would prove necessary if the actions we recommend in our dissent are implemented.

Each one of the following recommended actions listed below shares common features. If implemented, they would:

- Increase uncertainty about recovering already high-risk research and development investment.

- Substantially decrease the operating margin of the research and development–driven biopharmaceutical industry.

- Decrease or cease venture capital investment in creating new biotechnology companies.

- Decrease the ability to finance existing biotechnology companies.

- Decrease investments in research and development, leading to fewer new therapies and poorer health, as well as an overall long-term increase in health care costs.

The following are the recommended actions that we cannot endorse:

- Permitting government programs to negotiate individually will create a more conventional and dynamic market, but allowing the government to act as a single buyer across all programs would produce a near monopoly and functional price controls.

- Allowing the government to exclude a drug from its formulary based on cost alone raises serious moral and ethical issues. Imagine that a new drug is created that effectively treats a condition for which there never has been an effective treatment. Under these circumstances, it is hard to imagine the federal government or insurers telling patients or parents of affected children that the drug will not be made available.

Exclusion will also discourage investment in research and development. Companies currently assume risk in the research and development portfolio based on being able to (imperfectly) predict the returns on investment. The conditions conducive to investment have always been precarious, but the possibility of a zero return for a drug demonstrated to be safe and effective adds an entirely new dimension of unpredictability and risk. Undoubtedly some medically important research programs would not receive investment as a result.

- Allowing the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to permit importation. The FDA already permits importation of generics and biosimilars. It is the addition of “therapeutically equivalent” products that is new. Is the intention to import drugs made abroad that would be in violation of patents if brought into the United States? If so, we oppose this for the reasons stated at the beginning of this section. If that is not the intention, then importing generic and biosimilar products should be sufficient, and no new recommendation is required other than to encourage speed in the FDA importation approval process without sacrificing the evaluation of safety and efficacy.

-

Perhaps the intention is to allow enforced therapeutic substitution based on high costs. But substitution of one drug for another creates serious problems. It is not as easy as simply changing the oil in your car or substituting one bottle of pills for another. Imagine that a patient is adequately and stably controlled on a medication for high cholesterol or diabetes. Changing the patient to another medicine will involve communication about the new medicine. In many cases, the doctor will want to see the patient after the switch to make sure that the patient is not experiencing side-effects from the new medicine. In almost all cases, blood tests will be needed to determine if the patient’s condition is under control on the new drug. If good control is not obtained, the dose will need to be adjusted, or the patient will need to be switched to yet another medicine. All these maneuvers will cost the health system money. Furthermore, there is evidence that approximately 10 percent of patients who are asked to switch wind up discontinuing the medication; they are then untreated for a condition that requires treatment. This contributes to poorer outcomes and increased costs long term.

- Special arrangements to import branded drugs is a recommended action by the committee. Drug importation raises safety and practical issues. Four prior commissioners of the FDA have advised strongly against importation. Drug safety cannot be ensured, nor can the stability of the supply. How could a foreign country consistently provide supplies of medicines to the population of the United States that is many times larger than its own? Importation channels also facilitate the entry of counterfeit medicines—both a medical and economic problem in many other countries. Finally, importing drugs based on price translates into importing the pricing mechanism of other countries. Functionally, it translates into importing price controls into the United States.

- The committee also reminds both the government and the industry that the government holds “march in” rights in certain situations. Such action would be an extraordinary precedent with implications for many industries, not just the biopharmaceutical industry. Marching in, if implemented, would chill for many years, perhaps for decades, the inclination to invest in research and development and to create new biotechnology companies. (Certain South American countries provide vivid examples.) Meanwhile, the outlier behavior that might trigger such action most probably would have soon self-corrected as a result of market pressure and public pressure based on past history.

- The recommended actions to substantially reduce or curtail direct-to-consumer advertising need to be better understood before making a recommendation. How much does direct-to-consumer advertising contribute to the cost of drugs? Would legislation in this arena be worthwhile in relation to the savings generated? Does direct-to-consumer advertising inhibit patient access or enhance it? The “juice may not be worth the squeeze.” And can anything be done without violating the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution? Even in the presence of direct-to-consumer advertising, it is physicians, not patients, who ultimately decide whether or not to write a prescription. We would want to know much more before endorsing a recommendation in this arena.

OUR CONCLUSIONS

The recommended actions provided in this report could have important societal impacts on health and the cost of health care—impacts that we hope will be positive. We endorse or modify those recommended actions that promise to promote health while generating economic benefit, especially for patients, all the while stimulating research and development investment for the future. However, in our view, several of the report’s recommended actions would produce a decline in research and development investments, ultimately leading to increases in health care costs.

Patients are often the “silent partners” without representation in discussions or negotiations concerning pricing. Patients are the most vulnerable financially, especially considering the structure of insurance coverage and its ability to obligate patients to pay despite having no voice. So, in any recommendations we need to keep patients in the spotlight and connect the dots so that any savings that are generated lead to financial relief for patients and improve access to needed medicines and vaccines.

The report’s collected recommendations have such potential impact that they should be modeled and piloted before full-scale implementation. Directives for modeling and piloting should have accompanied many of the report’s recommendations. Also, an assessment needs to be made of the dynamics and the impact of the collection of recommendations in aggregate. Furthermore, an understanding needs to be obtained of the trade-offs of current versus future benefits.

Whatever is ultimately concluded and recommended, abuse—as seen in the cases of Valeant, Turing, and Mylan—is unacceptable. In each of these examples, the companies chose bad strategies. But the inappropriate behavior was exposed rapidly, and the consequences were severe. So the system worked. Exposure was more rapid and more effective than legislation would likely have been. The examples of these bad business practices

serve as deterrents to other companies considering similar approaches. And when the system does not self-correct, measures should be taken to stop abuse.

Instead of accepting the full set of recommended actions offered by this committee, we have offered in this piece a different set that excludes several of its recommended actions. Our recommended actions include several of the same elements, modified in order to achieve sufficient impact without the same degree of accompanying damage. We wrote this dissent in the hope that it will be favored as a more attractive alternative to achieving the goal of ensuring patient access to affordable medicines.

This page intentionally left blank.