The Future of Low Dose Radiation Research in the United States: Proceedings of a Symposium (2019)

Chapter: 6 Symposium Participants' Considerations for a Future Low Dose Radiation Research Program

6

Symposium Participants’ Considerations for a Future Low Dose Radiation Research Program

Dr. Gray observed broad support within the radiation research and radiation protection community for a low dose radiation research program. At the symposium, this support came equally from those who are concerned about the risks at low doses of radiation and those who argue that the risks are currently overestimated and therefore lead to tighter-than-necessary regulations. Still, however, efforts to re-establish a low dose radiation research program have not yet been successful.

Dr. Gray encouraged symposium participants to share their opinions on elements that could facilitate establishing and maintaining a successful low dose radiation program. This chapter provides an integrated summary of the participants’ thoughts on these issues as well as opinions on possible next steps.

6.1 POSSIBLE ELEMENTS OF A LOW DOSE RADIATION RESEARCH PROGRAM

The rapporteur distilled eight elements that could facilitate establishing and maintaining a successful low dose radiation research program: (1) a leadership team, (2) an appropriate model for organizing the research, (3) strategic planning, (4) goal-oriented research, (5) multidisciplinary research, (6) independent review, (7) infrastructure, and (8) sustainable funding.

The views of the symposium participants on these elements are discussed in the following sections.

6.1.1 Leadership Team

Different organizations and individuals with special interests and often opposing views on the risks of low dose radiation have not yet cooperated to gather interest and support for the low dose radiation research program. Instead, they often focus on the points of disagreement, which typically evolve around the appropriateness of the linear no-threshold model in radiation protection. Consequently an effort to build a joint and well-rounded argument about the need for additional research on low dose radiation has been unsuccessful. This became obvious at the symposium when participants disagreed in a number of instances about the framing of the societal implications of low dose radiation research uncertainties.

Dr. Barker, who led several large biology initiatives (see Section 5.2), identified the need for a leader (or a leading team) to take the role of synthesizing the facts and ideas around the low dose radiation research issues and composing them in a way that they represent the different interests and viewpoints. This way, according to Dr. Baker, a leader could facilitate buy-in and commitment of all parties to join the effort, and guide those with opposing views toward a common goal. The leader also becomes the knowledgeable and trusted communicator of arguments for a low dose radiation research program to Congress and potential sponsors. Dr. Barker and Mr. Greenbaum reflected on their experiences and said that Congress generally shows support to large research programs that have the ability to provide game-changing new information to inform policy decisions.

Dr. Waltar expressed his disappointment that during the panel discussion of government representatives (see Section 3.1) there did not appear to be an obvious leader for the program. Dr. Hertel added that, during the annual visit of the Health Physics Society with several government agency representatives, he also was unable to identify a federal agency that is willing to lead this effort.

6.1.2 Appropriate Model for Organizing the Research

A future low dose radiation research program in the United States has almost exclusively been thought to follow the same model as the previous Department of Energy (DOE)-managed program that was terminated in 2016. However, a number of different models were described at the symposium:

- A single-agency government program. This is the model previously used by DOE’s low dose radiation research program and the model that Congress has continued to support in recent legislation.

- A multi-agency government program. This is the model used for The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) initiative described in Section 5.2.1.

- A multi-agency government program coordinated by the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Two programs that use this model were discussed at the symposium:

- Under the American Innovation and Competitiveness Act of 2017, OSTP’s National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) coordinates federal efforts related to radiation biology and formulates scientific goals for the future of low dose radiation research in the United States.

- Under the National Quantum Initiative Act of 2018, OSTP/ NSTC chartered a subcommittee on quantum information science, tasked with coordinating research and development in quantum information science and related technologies within the government.

- A government-managed program overseen by an independent scientific organization. An example of organized research that uses this model was the Airborne Particulate Matter Research Program presented in Section 5.1.1. The National Academies oversaw the program and provided the strategic plan for its execution.

- A government–private sector partnership. Examples of that model include the Health Effects Institute (HEI) described in Section 5.1.2, the I-SPY 2 trial described in Section 5.2.2, and OSTP’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies initiative launched in 2014 to improve understanding of the human brain.

- An internationally coordinated research program. This approach is discussed in Section 2.5 and was supported by a number of participants, including Drs. Lazo, Brooks, Cool, and Klokov. Dr. Lazo shared his observation that the United States has not traditionally sought coordination with other countries to answer important research questions. Instead, the approach of the United States is “local” and the federal government tends to rely on its own resources and skills.

- A hybrid model that incorporates elements of the models above. Mr. Greenbaum proposed that perhaps subsets of the low dose radiation research work might be organized under two or more of the models outlined above. Symposium participants seemed to favor a hybrid model because they indicated a role for the federal government, stakeholder societies and interest groups, and international collaborations to tackle low dose radiation research questions (see Figure 6.1).

- Incorporating low dose research within a larger established program. A symposium participant asked whether it would be possible to incorporate low dose radiation research within a larger established program such as one that focuses on cancer research. Most symposium participants did not show support for this model because of the concern that the effort would be diluted and would be focused on a single endpoint, cancer.

Symposium participants did not discuss the strengths and limitations of the different models for organizing low dose radiation research.

6.1.3 Strategic Planning

Dr. Barker, Dr. Brooks, Mr. Greenbaum, and Dr. Kreuzer were among the symposium participants who highlighted the importance of setting direction and priorities of a program by designing a multi-year strategic plan. The strategic plan is also vital for coordination among different organizations who conduct the research because everyone subscribes to a common formalized roadmap and uses available time and resources to achieve the

program’s goals. This plan, in order to be effective, would include timetables, milestones, and cost estimates, and it would be adjustable based on new circumstances to improve both the relevance and timeliness of the program’s research activities.

Mr. Greenbaum highlighted the value of involving a trusted and reputable independent organization in the strategic planning for the program and in monitoring its implementation and research progress using best scientific practices. In addition, this independent oversight alleviates the reality or perception of conflicts that would otherwise appear if those with policy agendas make decisions about the allocation of program resources and also review the effectiveness of the program.

6.1.4 Goal-Oriented Research

Several symposium participants, including Dr. Ansari, Dr. Cool, and Mr. Greenbaum, noted that, like any other scientific topic, the opportunities for research in low dose radiation are numerous. However, because funding is likely to be limited, focusing research on issues of highest priority and relevance to radiation-related policy decisions would be most efficient. Mr. Greenbaum said that the relevance of a program is determined by the specificity to which its research addresses the questions of interest and the timing of the release of the scientific findings. He identified the relevance of HEI’s work on air pollution policy as an important element of the institute’s success and added that relevance is one of the parameters by which research projects are judged by the HEI review committees.

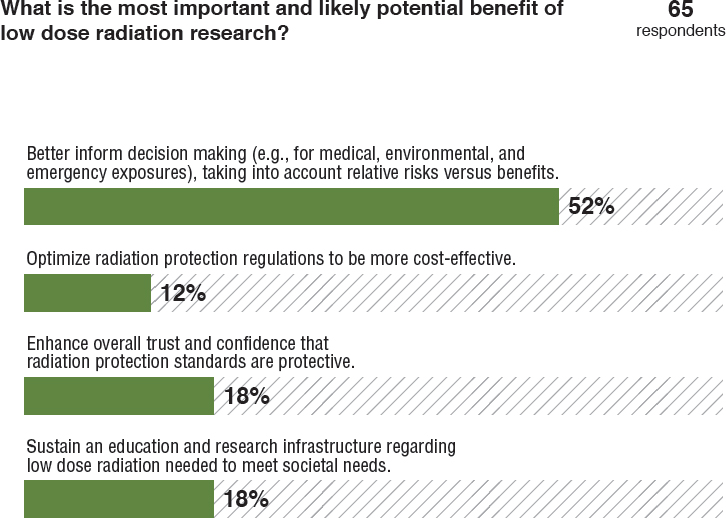

Symposium participants were polled on what they consider the most important and likely potential benefit of low dose radiation research (see Figure 6.2). The majority thought “to better inform decision making” as the most important contribution of such a program.

Dr. Ansari suggested that to identify the issues of highest priority for the low dose radiation research program, a process similar to the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Data Quality Objectives (DQOs) (EPA, 2006) could be used. A DQO process starts with stating the problem and identifies the information required to support a decision.

6.1.5 Multidisciplinary Research

A number of symposium participants recognized that bringing together scientists from a variety of disciplines to work on a common scientific question can lead to creative and high-impact research. Dr. Kreuzer said that at the Multidisciplinary European Low Dose Initiative (MELODI), all projects need to demonstrate that they are following a multidisciplinary approach to tackle a question. In her view the biggest advantage of this approach is

that the different disciplines can supplement each other, making research findings more robust. Also, the quality of research and its relevance to policy decisions will likely be improved if that research is the result of active deliberation among experts of different scientific backgrounds.

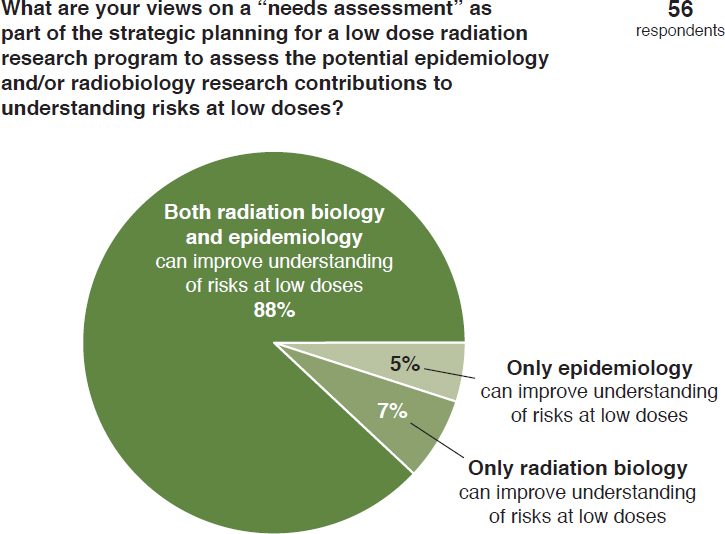

It was evident from the symposium discussions that the approach of fragmenting radiation biology and epidemiology research is not effective and both disciplines would probably be needed to address critical gaps in low dose radiation risks (see Figure 6.3 for the results of the Slido poll). Ms. Cindy Folkers (Beyond Nuclear) also argued in favor of radioecology to be part of the low dose radiation research program and Dr. Cool thought that incorporating knowledge from chemical toxicity can help address mechanistic questions related to low dose radiation effects.

Dr. Paul Locke challenged the symposium participants further and asked whether there is a need to integrate social science and specifically risk communication research in a future low dose radiation research program in the United States. A number of participants responded to the question directly and others provided comments relevant to this topic at some point during the symposium. Participants recognized that there are different goals of risk communication research. For example,

- Help the radiation community frame a consistent public message concerning low dose radiation risks. Dr. Brenner said that incorporating risk communication in the program is challenging when scientists do not know what the message is about risks at low doses. Ms. Jessica Weider (EPA) was in favor of risk communication research being incorporated into the program. She suggested the goal could be to help the radiation community reach consensus on what the public message about risks at low doses of radiation needs to be based on existing scientific knowledge. She added that this message would need to be adjusted as new knowledge about low dose radiation risks becomes available through the low dose research program or other sources but also by learning how non-radiation experts communicate risks from other hazards.

Dr. Ansari also saw value in risk communication research to help the radiation community better frame public messaging in different radiological scenarios. Effective public messaging can help scientists and government representatives build trust with members

- Understand the concerns of the general public and prioritize responding to these concerns. A symposium participant said that the low dose research program could help improve risk communication through audience research aiming to identify the stakeholders’ concerns and support technical scientific projects that directly address those concerns. For example, a common concern is whether the radiation protection system sufficiently protects those with higher sensitivity to the adverse effects of low dose radiation. To respond to this concern, research projects could aim to identify radiation susceptibility genes.

Federal agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and EPA have considerable experience with audience research. CDC, for example, often supports roundtable meetings to determine what the general public’s views are on topics that relate to radiation emergencies, to identify gaps in the agency’s ability to address those concerns, and subsequently to identify steps that can be taken to help close those gaps (CDC, 2018). CDC also uses audience research to test the efficiency of its communication tools.

- Train scientists to appropriately report radiation risks. Drs. Berrington de González, Preston, and Gray did not take a position on whether risk communication could be part of a future low dose radiation research program but recognized that researchers need to choose the most meaningful ways to present their findings to avoid hampering the readers’ understanding of the impact of these findings. For example, to report absolute risk estimates and not just relative risks in scientific papers. Dr. Preston also commented on the proper use and interpretation of the p-value when conveying the statistical significance of scientific findings (Wasserstein and Lazar, 2016).

Dr. Anderson said that the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health uses risk communication experts to train scientists on how to communicate new findings to workers and to prepare pamphlets or other products they use to communicate the study results.

of the public and give them the confidence that the radiation protection system is based on the best available science.

Dr. Brooks said that when DOE’s low dose radiation research program started, it supported projects on risk communication. However, these projects were discontinued soon after. He disagreed with that decision and

identified the absence of risk communication research in the previous DOE low dose radiation research program as a limitation and a point of failure of that program. As noted in Section 2.2, Dr. Kreuzer noted that MELODI made a decision to have a dedicated program for risk communication, separate from the program that supports epidemiology, biology, and other technical projects.

6.1.6 Independent Review

Independent review of research projects has become an essential component of scientific programs because it is generally thought that those who manage the projects may not be their most objective judges. It can improve both the technical quality of projects and increase confidence in the decision-making process.

Independent reviewers are typically experts in the field who are not constrained by the program’s organizational politics and therefore can be more open and frank when judging research projects. Symposium participants discussed that independent review can happen at different stages: to decide what projects are funded by the program, to monitor progress of the projects and improve them or identify projects that lack technical merit and need to be discontinued, and to evaluate whether findings from the project are described accurately.

6.1.7 Infrastructure

Experience from MELODI, TCGA, and other programs showed that significant investments could help build the infrastructure for carrying out large research programs, especially if they involve multiple organizations. Dr. Barker suggested that a pilot study might be needed to test that infrastructure and make necessary adjustments. Three categories of infrastructure were discussed at the symposium as crucial for building and maintaining a low dose radiation research program:

- Professional infrastructure. The decline in the number of radiation professionals is a well-recognized problem in radiation research and radiation protection (NCRP, 2013). Symposium participants noted that there are few professionals in the pipeline to fill current and future needs in radiation research, radiation regulatory policies, medical applications of radiation, nuclear waste management, and other areas. Some participants expressed concerns that, following the retirement of the small group of established radiation professionals, there will be a major gap between needs and capabilities unless action is taken. Dr. Brenner, Dr. Al-Nabulsi, and

- Facility infrastructure. Dr. Dauer cautioned about the shrinking radiation facility infrastructure in the United States and elsewhere. The number of federal research facilities, academic laboratories, and training programs in radiation are also declining sharply and rebuilding will be needed to support the needs of a low dose radiation research program, he added.

- IT infrastructure. A number of symposium participants recognized that IT infrastructure is a key enabler of scientific advances by facilitating data sharing and by securing data management. However, a number of organizations still try to resolve the many ethical, legal, manpower, and other issues related to establishing and maintaining such infrastructures. Also, within the United States, it was unclear how existing and developing systems such as DOE’s Comprehensive Epidemiologic Data Resource and the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) epiSphere, both set to store radiation epidemiology data, will be coordinated, if at all. Dr. Richardson was not optimistic that a common IT infrastructure to support coordinated research in the United States could be established. He cited different inter-agency policies for data and biosample sharing as the biggest impediment.

others identified a future low dose radiation research program as a means to revive interest in radiation education and training and to maintain the professional infrastructure for radiation protection.

6.1.8 Sustainable Funding

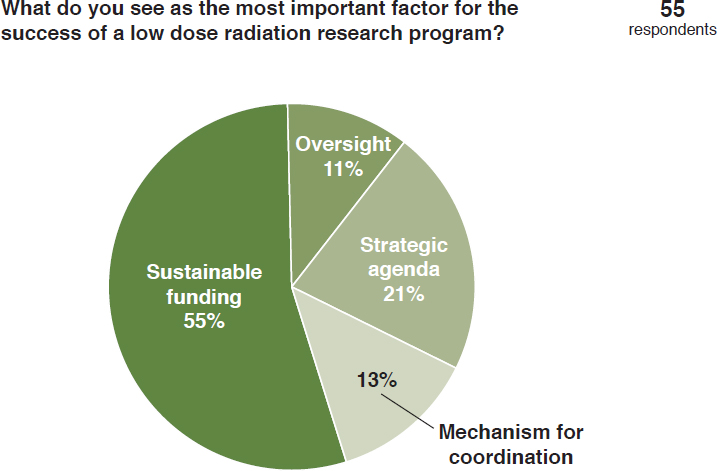

Symposium participants who responded to the Slido poll on important elements for the success of a low dose radiation research program thought that sustainable funding is the most important one (see Figure 6.4). A number of symposium participants commented on the need for long-term financial commitment to establish and maintain a low dose radiation program and expressed concern that the typical 1-year appropriations cycle within the federal government may not allow longer-term research projects to be successful despite their technical merit. Others recognized that the level of program funding is an indicator of the sponsors’ commitment to advance the research in the field.

There was no discussion at the symposium on the appropriate level of funding for a low dose radiation research program in the United States. However, some experts discussed the funding levels of their research programs. For example:

- DOE’s Low Dose Radiation Research Program reached a high of $28 million and progressively dropped to about $13 million as

- In Europe, funding for radiation protection and medical low dose radiation exposure is about €6 million annually.

- Funding for low dose radiation research at the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories is $7 million per year.

- In 1997, Congress appropriated $50 million for EPA to establish a research program on particulate matter (PM2.5). Funding for PM research continues today within EPA’s Air, Climate, and Energy Research Program and was about $95 million in fiscal year 2019.

- HEI receives about $10 million per year in funding from EPA and the worldwide motor vehicle industry.

- The total cost for the TCGA project that lasted for 13 years and was funded by NCI and the National Human Genome Research Institute was about $375 million.

priorities of the department shifted and the program was finally terminated in 2016.

Symposium participants also raised the question of how sustainable funding can be achieved. It appeared that the ability to show to the sponsoring agencies that the program’s goals continue to be met and that the program has mechanisms in place (e.g., strategic plan, oversight, and independent reviews) to regularly assess its performance could help

with achieving sustainable funding. Dr. Barker commented that typically the government contributes significant funding to research programs but noted that having multiple and diverse funding sources, as is the case for government–private sector partnership programs, might help with securing funding in the long term.

6.2 SOME POSSIBLE NEXT STEPS SUGGESTED AT THE SYMPOSIUM

In closing, Dr. Gray gave symposium participants a task: to send via Slido their opinion on how to move forward with setting up a low dose radiation research program. During the symposium, 10 participants responded to the task. Their verbatim responses are listed below:

- Need to get funding agencies on board.

- Identify a strong and motivated leader.

- We need to unify on the issue that must be addressed by low dose research. We do ourselves a dis-service to be seen as arguing with each other.

- Decide to proceed.

- International coordination is an important aspect of moving forward.

- Find a good leadership team.

- How does the low dose research community identify one or more “champions” to make the case of need for the research?

- Have NCI greatly increase funds for radiation research.

- DOE has a responsibility for worker protection as do other agencies. They should ante up for a focused research effort.

- Bring the community together again in a similar forum to discuss next steps.