The Use of Systematic Review in EPA's Toxic Substances Control Act Risk Evaluations (2021)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Exposures to industrial chemicals in food, water, air, and consumer products can cause harm to human health and the environment. The 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA; Pub L No. 94-469) provided the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (OPPT) with the authority to regulate chemicals in commerce. Subsequently, some public health and environmental groups concluded that TSCA was not sufficiently effective, particularly with regard to the regulation of existing chemicals (Bergeson 2016). In 2016 with bipartisan support, President Barack Obama signed the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act (“Lautenberg Act”) (Pub L No. 114-182), overhauling TSCA after 40 years. The Lautenberg Act provides the agency with increased authority to regulate chemicals existing before the 1976 TSCA was amended. For example, the Lautenberg Act requires evaluation of existing chemicals. Additionally, the agency must adhere to clear and enforceable deadlines. Chemicals are assessed against a risk-based safety standard. The risk evaluations consider both human health and ecological risks and must consider risks to susceptible and highly exposed populations; unreasonable risks identified in the risk evaluation must be eliminated; and the agency is provided expanded authority to more quickly require development of chemical information when needed.

The new authority afforded to the agency also put tremendous time pressure on OPPT to assemble teams, promulgate rules, and draft the guidance documents and related operating procedures that prescribe how OPPT responds to its mandate. The Lautenberg Act also required strict statutory deadlines of 9 to 12 months for chemical prioritization, the process to determine which chemicals should undergo risk evaluations. The first 10 high-priority chemicals then underwent risk evaluations, which were to be completed within 3 years of initiation (Susanna Blair, presentation to the committee, February 28, 2020).

The Lautenberg Act required the agency to promulgate several rules to implement the new requirements and responsibilities under the law. These rules provide the agency a framework to carry out its authority under the Lautenberg Act, including the Procedures for Chemical Risk Evaluation Under the Amended Toxic Substances Control Act, referred to as the “Risk Evaluation Rule” (40 CFR Part 702, 82 FR 33726). The statute requires that the agency must establish by rule a process for risk evaluation and that the risk evaluation will contain a scope or problem formulation, a hazard assessment, exposure assessment, a risk characterization, and the determination of unreasonable risk. The draft risk evaluations also must use the best available science (see Table 1-1); integrate and assess reasonably available information

| Term | Definition in Rule |

|---|---|

| Best available science | Science that is reliable and unbiased. |

| Weight of the scientific evidence | Means a systematic review method, applied in a manner suited to the nature of the evidence or decision, that uses a pre-established protocol to comprehensively, objectively, transparently, and consistently identify and evaluate each stream of evidence, including strengths, limitations, and relevance of each study and to integrate evidence as necessary and appropriate based on strengths, limitations, and relevance. |

| Systematic review | No codified definition within the rule. |

on hazards and exposures for the conditions of use, including information on specific risks of injury to health or the environment and information on potentially exposed or susceptible subpopulations; describe the ecological receptors that EPA plans to evaluate, whether aggregate or sentinel exposures were considered, and the basis; account for the likely duration, intensity, frequency, and number of exposures under the conditions of use; describe the weight of the scientific evidence for the identified hazard and exposure; be developed without consideration of cost or other non-risk factors; be published in the Federal Register; and have at least a 30-day public comment period.

Within the Risk Evaluation Rule, the agency chose only to define terms used within the statute, including “best available science” and “weight of the scientific evidence” (see Table 1-1). The term “systematic review” appears within the definition of weight of the scientific evidence, but the term is not codified within the Risk Evaluation Rule. Page 33734 of the preamble to the Risk Evaluation Rule states that the agency asked commenters about the application of systematic review to the hazard identification.

Commenters both supported and opposed the use of systematic review; thus, the agency chose to leave a reference to systematic review in the preamble of the Lautenberg Act but not codify a definition. Furthermore, the preamble states that it will not limit the use of a systematic review approach solely to the hazard assessment but will use it throughout the risk evaluation process.

As defined by the 2011 Institute of Medicine report Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews, systematic review is “a scientific investigation that focuses on a specific question and uses explicit, prespecified scientific methods to identify, select, assess, and summarize the findings of similar but separate studies. The goal of systematic review methods is to ensure that the review is complete, unbiased, reproducible, and transparent” (IOM 2011, p. 1). Systematic review has become the foundation for assessing evidence to be used for decision making in a variety of health contexts, including medical care and public health. Well-conducted systematic reviews methodically identify, select, assess, and synthesize the relevant body of research, and clarify what is known and not known about the potential benefits and harms of the exposure being researched (Higgins et al. 2019). Key elements of systematic review include the following:

- Clearly stating objectives (defining the question);

- Developing a protocol, which a priori describes the specific criteria and approaches that will be used throughout the review process;

- Applying the search strategy to identify relevant evidence;

- Selecting the relevant studies (papers) using predefined criteria;

- Evaluating the internal validity (i.e., Are the study results at risk of bias?) and the quality of the studies using predefined criteria;

- Analyzing and synthesizing the data using the predefined methodology; and

- Interpreting and evaluating the synthesized results to draw a conclusion and specify level of confidence in that conclusion (Stephens et al. 2016).

In recent years, systematic review has been increasingly applied for gathering evidence within the risk assessment process to increase transparency, objectivity, and reproducibility. EPA has been adopting systematic review within the Office of Research and Development’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Program since the 2011 National Research Council review of the draft IRIS formaldehyde assessment (NRC 2011). That report suggested that systematic review would remedy problems identified in the processes used to develop the draft assessment. Systematic review approaches are now being used and developed by the European Food Safety Authority, the Office of Health Assessment and Translation of the National Toxicology Program, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and the Navigation Guide (Morgan et al. 2018; OHAT 2019; Schaefer and Meyers 2017; Woodruff and Sutton 2014). Additionally, the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization have collabo-

rated to develop a risk-of-bias tool for assessing data on prevalence of exposure. The newly developed methods are based on review of existing methods, influenced by consultation with experts, tested for validity and reliability, and published in the peer-reviewed literature (Pega et al. 2020). Methods have also been proposed for applying systematic review methods to risk evaluations for ecological receptors in a framework integrated with human health risk evaluations (Suter et al. 2020).

Many stakeholders called for the adoption of systematic review within TSCA risk evaluations, which is why EPA asked for public comment on systematic review when developing the Risk Evaluation Rule. In 2018, OPPT developed the document Application of Systematic Review in TSCA Risk Evaluations to guide the agency’s selection and review of studies (EPA 2018a). OPPT did not draw directly from the methods being developed in the IRIS Program in this document, or from other methods in development, and instead put together a new approach for evaluating evidence.

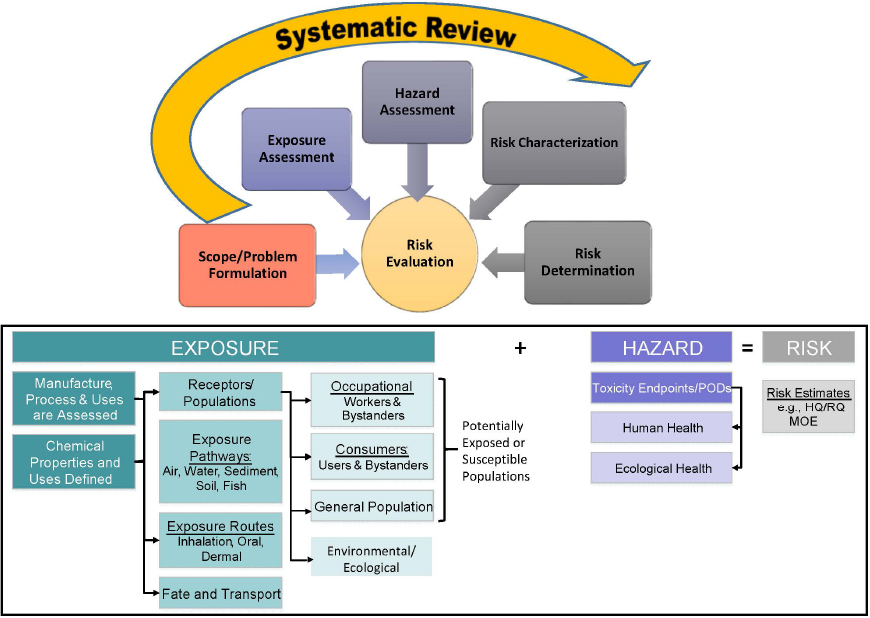

In these other existing frameworks, systematic review is typically applied to reviewing research for hazard identification (Whaley et al. 2016). OPPT has used systematic review to evaluate all lines of research that are integral to chemical risk assessment, such as exposure assessment and chemical and physical properties of the agent of concern (see Figure 1-1). The need to apply systematic review to types of studies to which it has not previously been applied has been offered by OPPT as the reason for developing its own approach (Francesca Branch, presentation to the committee, July 23, 2020).

THE COMMITTEE, ITS TASK, AND ITS APPROACH

EPA requested that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convene a committee to review the use of systematic review in TSCA risk evaluations. The committee included expertise in toxicology, epidemiology, risk assessment, exposure science, statistics, modeling, evidence integration, and systematic review; see Appendix A for biographical information on the committee. The verbatim statement of the committee’s task is provided in Box 1-1. To address its task, the committee

held a half-day public meeting during which OPPT presented an overview of systematic review under TSCA. OPPT also participated in three virtual public committee meetings, during which OPPT staff described tools used in searching and screening the literature, updates to their data evaluation and scoring procedures, and approaches to evidence integration supporting the exposure and hazard assessments. The presentations and posters described advancements that the agency has made since the publication of Application of Systematic Review in TSCA Risk Evaluations in 2018 (EPA 2018a). Stakeholders were allowed to provide written input to the committee throughout the review. In addition, opportunities for oral testimony were provided during two meetings.

During the first public meeting, OPPT clarified to the committee that it wanted the committee not only to consider the approach described in Application of Systematic Review in TSCA Risk Evaluations (herein the 2018 guidance document) and enhancements to the systematic review process reflected in documentation of the first 10 chemical risk evaluations but also how OPPT is planning to improve the use of systematic review in TSCA risk evaluations. These were broadly described at the committee’s three virtual meetings, which occurred in June, July, and August 2020. The committee took the following approach to the Statement of Task given the agency’s needs:

- The committee read and critiqued the 2018 guidance document.

- To consider the enhancements made to the systematic review approach in the first 10 risk evaluations, the committee reviewed the Draft Risk Evaluation for Trichloroethylene (TCE) and the Risk Evaluation for 1-Bromopropane (n-Propyl Bromide) (1-BP) (EPA 2020a,c). These evaluations were chosen because at the first meeting, EPA suggested that the 1-BP risk evaluation was a “typical risk evaluation,” and later OPPT suggested that the TCE risk evaluation was the “best example of integration.” The committee also critiqued the systematic review of the toxicology and epidemiology studies within the TCE risk evaluation using the “assessment of multiple systematic reviews” (AMSTAR-2) measurement tool (Shea et al. 2017). During its review of the TCE and 1-BP evaluations (including public comments, reviews from EPA’s Science Advisory Committee on Chemicals, and EPA’s response to the comments or reviews), the committee found significant overlap between the procedural steps taken in the two systematic review processes. Given that the TCE risk evaluation occurred later in time than the 1-BP assessment, and because it included a more detailed outline of the integration process, the committee chose to focus more heavily on the TCE risk evaluation in this report. Specific examples for 1-BP are used if there was a significant deviation from the process used in TCE.

- To consider enhancements to the TSCA systematic review process beyond the first 10 risk evaluations, the committee considered oral and poster presentations provided by OPPT at the committee’s public virtual meetings.

- The committee posed questions to OPPT following the first committee meeting to clarify aspects of the use of systematic review in the risk evaluations.

The committee then considered all of this information to determine whether the TSCA systematic review process is comprehensive, workable, objective, and transparent—the core evaluation measures of the Statement of Task. The committee also provides its recommendations with regard to steps that could be taken to improve the evaluation process as described in the 2018 guidance document and further elaborated in the evaluations.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into three chapters and three appendixes. Chapter 2 presents a critique of the TSCA approach to systematic review. It begins with a short overview of how systematic review has been adopted within chemical risk assessments and provides some general observations concerning the OPPT approach. For each systematic review step, the committee provides a brief overview of the state of the practice, describes how the step is applied in TSCA risk evaluations, critiques the approach used in TSCA risk evaluations, and then provides recommendations for improvement for each step. Chapter 3 addresses crosscutting and more general issues related to the use of systematic review in TSCA risk evaluations. Appendix A provides biographical information on the committee. Appendix B provides the meeting agendas and Appendix C provides a list of the documents reviewed by the committee.