Guidance for Measuring Sexual Harassment Prevalence Using Campus Climate Surveys: Issue Paper (2021)

Chapter: Guidance for Measuring Sexual Harassment Prevalence Using Campus Climate Surveys

![]() GUIDANCE DOCUMENT

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT

Guidance for Measuring Sexual Harassment Prevalence Using Campus Climate Surveys

Edited by Nicole M. Merhill, Kelley A. Bonner, and Arielle L. Baker

Authored by members of the Evaluation Working Group of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education1

About Products of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education

This Guidance Document is a product of the National Academies’ Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education, which presents information and identifies guidance based on existing research literature. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations or the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education. They do not represent formal consensus positions of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Copyright by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Learn more: http://www.nationalacademies.org/sexualharassmentcollaborative

___________________

1 See Author Information section for the names of Evaluation Working Group members.

Introduction

Measuring the prevalence of sexual harassment on a campus can be achieved by collecting population-based data in the form of a large-scale survey. The ability for such a survey to do so accurately, however, depends on many factors, such as whether the questions it contains have been tested to determine whether participants understand and interpret them as intended. The good news is that expert researchers have worked for decades to identify these factors so that organizations can use rigorous, evidence-based approaches to measure how and where sexual harassment is occurring. This progress is helpful because individual reports of sexual harassment to an organization through formal reporting channels, such as notifications to the Title IX Office, are not reliable indicators of the prevalence of the problem. In fact, it is rare for those who experience sexual harassment to file a report with their institution (NASEM, 2018)—studies show that approximately 2 to 7 percent of individuals do so (Rosenthal et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 1997; Wasti and Cortina, 2002)—so such numbers will be exceedingly low. The collection of accurate, reliable prevalence numbers positions institutions well toward developing informed plans for action, which will in turn lead to more effective strategies for preventing and addressing sexual harassment.

Questions about sexual harassment prevalence are often situated within a broader survey that asks questions about social concerns such as gender issues, respect, or culture—commonly called a “climate survey.” Climate surveys are an important way for organizations to understand and learn from the community’s experiences, as well as a way to demonstrate accountability and commitment to addressing the issue of sexual harassment. Conducting a campus climate survey better equips the organization to take targeted, effective action toward fostering a safer, more inclusive campus climate.

The purpose of this guide is to provide information specifically on conducting climate assessments to measure sexual harassment prevalence. Using peer-reviewed research and in consultation with experts2 from the fields of psychology, survey methodology, and sexual harassment research, each section of this guide describes key considerations for each step in the campus climate assessment process and identifies where there are gaps in the research knowledge. For example, efforts to assess sexual harassment prevalence in higher education have predominantly focused on the experiences of student populations, and only recently have options emerged to assess climate among faculty and staff; the information laid out in this guide reflects that disproportionality. Although qualitative assessments can be useful in understanding the ways in which harassment is experienced, they are unable to provide prevalence numbers and are therefore outside the scope of this document.

Each campus has a distinct set of needs, opportunities, and constraints, including around the use of language (see Box 1). Institutions are encouraged to think about how the guidance below might be adapted or refined to best meet its needs given its structure, community characteristics, and available resources, all while retaining its rigorous evidence base. This guide is by no means a comprehensive source of all information needed to conduct a climate assessment, nor a source for information on conducting surveys in general; rather, it is a compilation of key considerations to use when assessing the prevalence of sexual harassment in your organization through climate surveys.

Assembling Your Team: Who Should Be Involved?

One of the very first steps in undertaking a climate survey is to assemble a group of individuals to lead and advise the project. Research shows that

___________________

2 Experts consulted for this guidance document include Dr. Lilia Cortina, Dr. Jennifer Freyd, Dr. Kathryn Holland, and Dr. Vicki Magley.

BOX 1

Definition of Key Terms

In compiling this guidance, the Evaluation Working Group recognized the importance of defining terms that may be used variably across contexts.

Sexual harassment is a form of discrimination that includes gender harassment (verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey hostility to, objectification of, exclusion of, or second-class status about members of one gender), unwanted sexual attention (verbally or physically unwelcome sexual advances, which can include assault), and sexual coercion (when favorable professional or educational treatment is conditioned on sexual activity) (NASEM, 2018). Importantly, pervasive sexual harassment that creates a hostile work environment can constitute illegal discrimination (MacKinnon, 1979; USEEOC, 1980).

Target is a term used in research to describe an individual who experiences sexual harassment either directly or ambiently (Glomb et al., 1997; Parker, 2008). The term “target” is often used by researchers, but those who experience sexual harassment may prefer other terminology, such as “survivor,” “whistleblower,” or “truth teller.” In general, this document uses the phrase “those who have experienced harassment.”

People of color is an evolving term that emerged in the 1960s and now includes a broader group of individuals such as Black, Latinx, Asian, Mexican, Japanese, Chinese, and other groups that share a common societal place of either feeling or actually being marginalized (Pérez, 2020). Although this document uses the broad term “people of color” in order to stay consistent with the methodology of the literature that is being summarized, the Evaluation Working Group recognizes that systemic racism continues to oppress and impact the lives of Black and Indigenous people in ways that other people of color may not necessarily experience (Grady, 2020).

Man and Woman refer to any person who identifies as such, including but not limited to cisgender, transgender, and nonbinary individuals. The Evaluation Working Group recognizes that gender expands beyond this binary construct and acknowledges individuals who identify as nonbinary and/or with other genders where possible; however, this document does contain some binary language to be consistent with the methodologies of the literature that is being summarized.

partnerships of stakeholders from a broad cross section of the community assembling across multiple groups (like having a research team to provide input on the project and an advisory board to oversee the project) or as a single team is crucial in collaboratively promoting campus-wide change (Allen, 2005). As with all survey research, institutional review boards and survey research methods experts should be consulted, and involving an Office of Institutional Research will benefit the project (Farley, 1978; McMahon et al., 2016).

At higher education institutions, a cross section of the community might involve practitioners such as Title IX coordinators and ombudspersons; faculty and postdoctoral fellows; graduate, professional, and undergraduate students; and staff members whose offices may take action based on the results

of the survey, such as diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) staff, and human resources staff (see Figure 1). Importantly, involving those who belong to or identify with specific demographic groups being measured, as well as those with lived experience with the issue of sexual harassment, may prove valuable in framing questions and language in a way that builds trust with those groups and avoids harm. Although each member of the team has a unique and critical voice in the project, perhaps the most essential types of members to include are individuals with technical expertise in the area of sexual harassment research (NASEM, 2018) and structural inequality research. A team member with expertise in sexual harassment research can help ensure that the data gathered are reliable and valid (i.e., collected using scientifically rigorous methods). In addition to knowledge about responsible practices associated with protecting survey participants’ privacy, these experts will bring a greater understanding of how to best measure sexual harassment, what sexual harassment data mean, and how these data can be interpreted. Scholarly expertise in structural inequality will help to ensure the design, methodology, analyses, interpretation, and dissemination are attentive to the ways in which sexual harassment manifests for those historically underrepresented within higher education. Local faculty or research personnel may be well suited for these roles; however, institutions lacking expertise might consider partnering with regional or national institutions to acquire aid in their data collection and analysis (Driver-Linn and Svensen, 2017).

Additionally, institutional leadership plays an important role in any effort to assess sexual harassment prevalence (Banyard, 2014). Not only can those in leadership positions contribute institutional knowledge of campus sexual misconduct and learn more about climate issues that impact those in the community, but their involvement lends legitimacy to the project and may encourage the participation of other individuals, especially if that individual is viewed as a legitimate authority within that particular community (Cialdini, 1984; Dillman et al., 2014; Groves et al., 1992; Lichty et al., 2008). For example, for medical students at an academic medical center, a request for participation from the physician chief executive officer may be taken more seriously than from an administrator; for nurses, however, it might be a high-level nurse manager or well-regarded nurse researcher. Involving leaders in the survey process can equip them with the knowledge and context needed to champion anti-harassment efforts that are taken following the assessment. In any involvement or sponsorship, institutional leaders should publicly make it known that the goal of reducing and preventing sexual harassment is one of their highest priorities (NASEM, 2018).

Finally, consider the importance of rewarding, recognizing, and resourcing climate assessment efforts. Equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts by institutions are often hindered by a lack of sufficient resources and by the expectation that individuals who are most affected by these issues, particularly women and men of color, will assume a leadership role in promoting positive change without appropriate compensation, authority, or promise of reward or recognition (NASEM, 2020). It may be appropriate to provide incentives (financial, related to workload, or otherwise) to allow committee members to participate fully in your team.

Initial Considerations for Your Team

Once the members of your team have been identified, one of the first tasks your group may want to undertake is to examine and compile a list of relevant institutional information related to sexual harassment. Sometimes called a resource audit, this research method examines publicly available information and available resources within an organization and compiles them into a comprehensive listing (Stith et al., 2006). In this case, such an audit might include information about confidential and nonconfidential means of reporting harassment, support and advocacy services, mandatory reporting and/or responsible employee policies, anti-retaliation plans, etc., which campus offices with compliance responsibilities may already have on file. Documenting this infrastructure will be helpful as your team proceeds with the work; the information collected may be used to customize and/or referenced in survey questions, highlight resources for those who may want to seek support related to sexual harassment, or leveraged to create an action plan based on the data from the survey (Lichty et al., 2008; McMahon et al., 2016).

Surveys can be used to measure the climate and sexual harassment prevalence within the whole institution, specific schools or facilities, and/or specific subpopulations. In line with this, another early consideration for your team is to determine the scope of the population you would like to survey, including whether that population is large enough to assess. Privacy is a significant concern for those in underrepresented or smaller populations, in which case stratified or systematic random sampling can be used to oversample certain groups. This will, in theory, produce results that are generalizable to the entire study population (Clancy et al., 2017; Meyer and Wilson, 2009; Sable et al., 2006). If you have a small institution or unit in which it would not be possible to protect participant identities, other methods should be used to understand the climate.

Importantly, qualitative assessments (which are not explored in great detail here) are unable to provide prevalence numbers but may provide valuable insights into the ways in which harassment is experienced (see “Approaches for Collecting Additional Information” section).

In light of these complexities and others outlined below, your group may want to spend some time developing a “roadmap” to the project. One way to do this is to create a timeline for the project, which will lay bare points of pressure and flexibility within the project; help set expectations among your team and the campus community; and enable targeted, tailored action based on the results of the climate survey. It may also be a useful opportunity to discuss the communication strategy for your climate survey, including ways to incorporate community input, how to communicate the institution’s commitment to this issue, and the rationale behind why and how the survey is being administered. Communication considerations are especially important because informing the community and providing opportunities to influence decision-making can help build buy-in and trust for the process (Colquitt et al., 2013; Lind et al., 1990).

Your “roadmap” might also benefit from establishing a policy around how and to whom the data from the survey will be made available. In light of the sensitive and personal nature of sexual harassment, your group should prepare for requests from various community members who may be interested in using the dataset for their purposes; this might also necessitate establishing a minimum threshold of aggregate responses that you are willing to share. Having a policy in place up front will be useful toward informing participants about how their data will be used, and will mitigate concerns that the institution is hiding the survey results.

Diving into the Work: Which Survey to Use?

Your team has been identified and you have collected all of the information needed to begin the project. The next major milestone is to determine if you would like to use an existing survey or whether you’d like to create your own. Although there are many campus climate surveys available for institutions to use, in order to obtain accurate estimates of the problem, it is especially important to choose a survey that contains questions that have been tested by researchers to ensure they measure the intended experience.

To Collect Accurate Data, Use a Reliable and Validated Instrument

Over the past decade, sexual harassment researchers have developed and refined questions (often called “measures”) to ensure that they reliably measure the intended experience. A collection of these measures that are designed to measure a specific phenomenon make up a “survey instrument.” For assessing sexual harassment prevalence, many survey instruments exist, and it can be challenging for nonexperts to distinguish which ones are well validated—that is, which have been tested to determine how participants interpret the items and response options, and whether the items were understood and interpreted correctly.

The Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ) is widely considered to be the best instrument for assessing sexual harassment experiences in educational settings and is supported by extensive psychometric evidence (i.e., scientific confirmation that participants understand and interpret questions as intended) (Fitzgerald et al., 1995; NASEM, 2018). One aspect of the SEQ that sets it apart from other instruments is that it contains standardized questions about specific sexual harassment behaviors rather than asking about “sexual harassment” generally

(Cortina and Berdahl, 2008). Asking participants behavior-based questions is important because those who experience sexual harassment are unlikely to label their experiences as such. Furthermore, those who have experienced harassment may selectively decline to participate. Both of these outcomes will lead to inaccurate measurements (Holland and Cortina, 2013; Ilies et al., 2003; Krosnick et al., 2015).

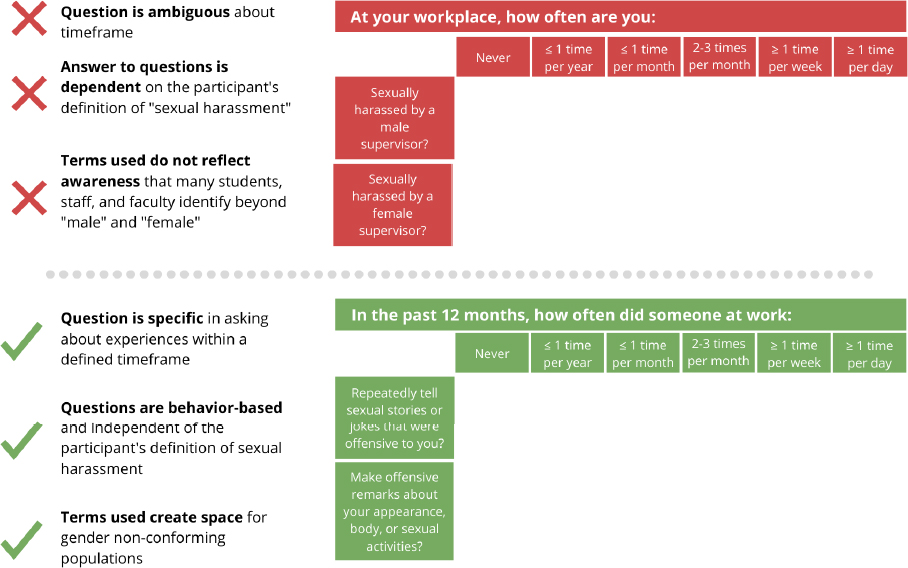

This means that it is important to avoid using terms such as “sexual harassment,” “sexual assault,” and “sexual misconduct” in survey titles and invitations, and in questions and answers designed to assess prevalence (see Figure 2). Rather, questions about sexual harassment should be situated within a broader survey that asks questions about social concerns such as gender issues, respect, or culture.

The only occasion in which these terms may be used within the survey is to collect information unrelated to prevalence—for example, if your institution would like to determine how many people might label their experience as sexual harassment (as a way to assess awareness of what constitutes sexual harassment) or to understand how aware your community is of available resources or support for sexual harassment. In these cases, it is important to consult with the members of your team with scholarly expertise in survey methodology and sexual harassment.

Another way that the SEQ is distinct from other instruments is that it uses questions that ask about gender harassing behaviors (both sexual and nonsexual), not just sexual coercion and unwanted sexual attention. Collecting data around gender harassment is important because it is the most

SOURCES: Fitzgerald et al., 1995; Stark et al., 2002.

prevalent form of sexual harassment (Box 1); when sufficiently severe or pervasive, gender harassment does the same professional and psychological damage as an isolated instance of sexual coercion (Langhout et al., 2005; Leskinen et al., 2011; Sojo et al., 2016). When studies do not collect data about those who have experienced gender harassment, particularly gender harassment in the form of “sexist hostility” (Stark et al., 2002), it results in lower prevalence rates, underestimating the true prevalence of sexual harassment.

To Collect Accurate Data, Use Research-Based Survey Practices

Building upon the strong foundation of the SEQ, sexual harassment and evaluation researchers suggest a few additional considerations in order to capture the most accurate prevalence data:

- Measure experiences over the most recent 1- to 2-year time period and only since the population being surveyed has been enrolled or employed at the institution (see Figure 2). Surveys that are designed to capture a longer time period may result in skewed prevalence rates that misrepresent the current climate. Incidence rates may be higher because including more time means that more people are likely to have experienced such behavior. Further influencing results is the effect of memory deterioration, leaving behind only sexual harassment experiences that imprint a lasting memory, which can exclude everyday sexist comments or harassment occurring ambiently within the environment (NASEM, 2018).

- Include demographic questions about sexual orientation, disability status, race, ethnicity, and religion, and reflect an inclusive awareness that many students, staff, and faculty in higher education identify with gender categories other than “woman” or “man” (see Figure 2). Research shows that people of color, sexual and gender diverse individuals, and those with disabilities experience harassment at higher rates than their white, cisgender, and heterosexual counterparts (Basile et al., 2016; Cortina, 2004; Cortina et al., 1998; Konik and Cortina, 2008; Lombardi et al., 2002; Schilt, 2010; Schilt and Connell, 2007; Settles et al., 2008). It is important to collect information around their unique experiences so that strategies tailored toward supporting these individuals can be developed (see below for more information about protecting vulnerable populations).

- Separate measures of mental/physical/professional/educational outcomes from questions that ask the participant to recall their experiences of sexual harassment. This can be accomplished by putting outcome questions (e.g., date of graduation, current employment status, etc.) at the beginning of the survey, or ideally by separating them across several pages of other items, which helps to address the impact of experience recollection on participants’ ability to complete other questions. It will also help limit common method bias: changes or variations in a participant’s responses over the course of the survey (Holland et al., 2014, 2016; Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Revising and/or Adding Questions to an Existing Survey

If your team is not looking to build a survey from scratch, you can draw from the many campus climate surveys available for institutions to use. In doing so, you’ll want to choose a survey that adheres to the best practices outlined previously (see also Box 2). One such survey that is accessible and freely available for use is the Administrator Researcher Campus Climate Collaborative (ARC3) survey (NASEM, 2018). The ARC3 survey uses instruments based on the SEQ to ask behavior-based questions measuring sexual harassment, including all of its subtypes, which helps ensure that the data institutions collect are reliable and valid (Swartout et al., 2019). Importantly, the ARC3 survey was developed by expert researchers in the area of sexual harassment and gender-based violence, in collaboration

BOX 2

Choosing a Survey: An Opportunity for Institutional Courage

At this stage, a practical consideration for many institutions is whether to use a survey that has been widely adopted, or to use a more rigorous survey that may be used at fewer organizations. Provided comparisons are done carefully, surveys that are widely adopted provide an opportunity to examine data across years and across institutions, but may not be up to date with the best practices identified by research. Surveys that use the latest, most rigorous methods, on the other hand, may not be as widely adopted and may reveal sexual harassment prevalence rates higher than their peers. This represents an inflection point at which the survey team and institutional leaders have the opportunity to be powerful levers for change, prioritizing safety over reputation by engaging in the best social science methods available and providing their community with an accurate diagnosis of the issue. According to institutional courage researcher Dr. Jennifer Freyd, “Each college and university has a choice: nervously guard its reputation at the profound expense of student wellbeing or courageously invest in student safety, health and education. College campuses need to know what they are fighting. Enabling the methodical collection of data—and encouraging their transparent distribution and study—will signal to campus communities across the country that institutional betrayal can be replaced by institutional courage” (Freyd, 2014).

with Title IX professionals, campus law enforcement, advocates, and counselors. Organizations can request additional information about the survey, as well as additional guidance about administering such surveys, from the ARC3 website (ARC3, 2015).

Many higher education institutions have used either or both the ARC3 survey and the SEQ to create customized surveys of their own. Although the ARC3 was initially created to measure the prevalence of harassment among undergraduate and graduate students (Swartout et al., 2019), it is actively being expanded to other ecosystems in higher education, including faculty and staff (Flack et al., 2019) and medical environments (Vargas et al., 2020). Whenever the SEQ or any other previously validated instruments are used, it is important to record and report any alterations to item wording, order, scale, or other aspects. This is because alterations may impact the reliability of the survey and the validity of the results; they may also make your data less readily comparable with those of other organizations using similar instruments.

No one organization is the same, so it may be necessary to add, remove, or adjust questions drawn from the chosen survey instrument to better suit the specific environment in which your survey is to be administered. Minor changes such as removing words that do not apply or adapting pronoun fields can help tailor it to the survey’s target population. In these cases, retaining the items’ original wording would influence validity more than the small edits. Your team can document edits to a survey instrument by noting the original form of the scale or item and how it was updated, as well as why the change was made (McMahon et al., 2016); for example, see the Department of Defense SEQ (Stark et al., 2002) and the National Institutes of Health SEQ (ICF Next, 2020).

Before Initiating the Survey: Administration Considerations

Once your team has chosen or created a survey that is consistent with the best practices outlined above, you may be eager to begin sharing it with your community. However, before jumping in, there are a

few final considerations that are especially important to consider for sexual harassment prevalence surveys.

Choosing Whether to Make Your Survey Anonymous or Confidential

When surveying a population about sexual harassment experiences, it is important to protect the identity of the survey participant. To encourage open self-reports, it is important that survey responses are confidential, if not anonymous (Box 3) (NASEM, 2018). Those who have experienced sexual harassment may be reluctant to respond to a survey on the topic or to acknowledge their experiences because sexual harassment can be stigmatizing, humiliating, and traumatizing; those who have experienced harassment may also fear retaliation (Bumiller, 1987, 1992; Greco et al., 2015).

Unfortunately, no consensus exists around whether sexual harassment prevalence surveys should be confidential or anonymous. In consulting with sexual harassment researchers, Dr. Lilia Cortina felt that confidential surveys can accomplish an organization’s goals, especially when participants are reassured that they will never be identifiable to members of their institution and that no one at their institution will ever have access to their raw data (including quotes from answers to open-ended questions). In this case, Dr. Cortina noted, it is helpful if the survey team is not part of the unit under study, or even a part of the institution, and that this is clearly communicated to the participants. Dr. Magley, however, expressed a preference for anonymous surveys, stating that in her experience, providing such reassurances does not make participants feel comfortable enough to voluntarily provide identifying information. A “middle ground” approach suggested by a third expert, Dr. Jennifer Freyd, would be for the data collection team to destroy all identifying information at the end of the assessment, essentially making the confidential survey anonymous. In this case, the institution would need to consider whether the identifying information might be needed longitudinally.

Although there is not yet consensus regarding whether surveys should be confidential or anonymous, if your team decides to ask for identifying information, data aggregation methods ought to be used to protect and reassure participants (Swartout et al., 2020). Basic information (such as class year or range of years employed at the institution) is usually common enough that it will not reveal the identity of individual subjects (McMahon et al., 2014), but it is important to remember that asking participants to provide it may raise doubts that their responses will be kept fully private. One way to

BOX 3

Anonymous Versus Confidential: What Is the Difference?

In practice, the distinction between “anonymous” and “confidential” in the context of climate surveys varies widely. Generally, “confidential” surveys may ask participants for identifying information (email addresses, identification numbers, names, etc.) so that their responses can be matched to them. “Anonymous” surveys do not collect identifying information and have no way of matching participants to their responses. Greater standardization of terminology around these definitions would be beneficial to the higher education community.

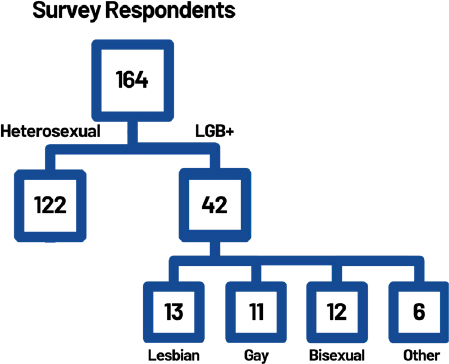

NOTE: LGB+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other.

overcome this concern is to explain to participants up front that the results will only be shown in the aggregate so that an individual participant is not identifiable. If the raw climate data will be shared or accessible to a wide range of people (inside or outside of the organization), demographic data can be collapsed to further protect the identity of participants in smaller institutions, for example, heterosexual compared to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other, rather than a more detailed breakdown of sexual identities (see Figure 3).

Ethical and Safety Guidelines

Related to the privacy concerns expressed above, it is important for any organization looking to implement a survey to consider all ethical and safety guidelines for research on human subjects. The nature of issues related to traumatic experiences, such as sexual harassment, means that ethics, safety, and confidentiality are even more important than for other areas of research (WHO, 2001). It is therefore important to provide participants with information about where to go for support at the onset of the survey (McMahon et al., 2016) and including such resources throughout all “pages” of the survey makes them readily accessible to those who might need them as they answer the survey’s questions. To help the offices that provide such support prepare for those who might seek it, your team may want to alert staff to the timeline of the survey’s administration.

Ethical considerations also underline the importance of conducting a survey that adheres to best practices outlined in research. Inaccurate data resulting from an unethically administered survey could be used to question the importance and legitimacy of the topic (WHO, 2001). In the case of sexual harassment prevalence surveys, research shows that asking individuals about prior trauma (such as a sexually harassing experience) in a responsible, trauma-informed way presents a minimal risk of psychological distress (Gómez et al., 2015; Jaffe et al., 2015). In fact, some researchers argue that it is unethical not to ask about abuse (Becker-Blease and Freyd, 2007; Edwards et al., 2007). Dr. Cortina advises that “participation in climate surveys is often a positive experience for targets, and many welcome the opportunity to share experiences in a confidential setting.” Following the scientific methods described in this document, as well as safety guidelines and

BOX 4

Institutional Example: Learning How to Increase Participation Rate Using Student Focus Groups

In addition to the primary steering committee that led the institution’s 2019 climate survey efforts, Harvard University formed two working groups to provide specific recommendations on how to most effectively engage the community with the survey. The two working groups (comprised of combinations of Title IX staff, public affairs and communications staff, students, institutional research staff, and survey experts) carried out student focus groups and targeted outreach to solicit feedback on draft/proposed questions, promotional materials, and methods for outreach and engagement with the community. Harvard found that engaging students from both graduate and undergraduate populations was crucial to the success of the climate survey. While the institution was able to draw from experience based on its first iteration of the survey, it learned that methods of engagement differed significantly between 2015 and 2019. For example, while email was an effective tool for communication in 2015, it was found that students were more inclined to view a Facebook video or post by their peers than to read an email received from an administrator. The institution also learned from students that the timing of emails greatly influenced participation rates. For example, students were less likely to complete the survey if links were sent at midday than if they were emailed early in the morning. Modifying the timing of emails and the method of promotion increased student participation in the survey. Without student engagement and participation of student influencers in the working groups, the participation rate would have been much lower.

standards, will help your team collect data on sexual harassment prevalence in the most accurate, ethical way possible.

Frequency and Timing of Surveys

One major challenge that your team will encounter in the administration phase is determining what time of year and how often the survey should be scheduled in order to optimize both the response rate and quality of the data gathered. Unfortunately, research is limited in this space and there is not yet sufficient evidence for the best time or interval for climate surveys to be administered. Some suggest that the best time to schedule a survey for students is in the spring (a time at which most participants have been on campus for several months) and/or when student life is most “normal” (i.e., not during exam weeks or over school breaks). When surveying beyond student populations, an institution might consider a time when there are few or no other campus-wide surveys open (Flack Jr et al., 2008; McMahon et al., 2016).

As to how frequently a survey should be given, some states legislate that climate surveys must be conducted every 2 to 3 years (Cuomo, 2015; Quijano, 2019). A group of Association of American Universities institutions, on the other hand, contend that less frequent surveys, for example, every 4 to 5 years, “provides institutions the necessary time, flexibility, and resources to conduct other important data collection efforts” (Driver-Linn and Svensen, 2017). As evidence is not yet sufficient to support a specific time of year or interval, it is clear that additional research is needed in this area. Whatever time of year your team decides to implement the survey, any effort to limit participants’ willingness to engage with your assessment—often called survey fatigue—will boost the quality and amount of data acquired (see Box 4).

Finally, researchers recommend that efforts to conduct campus climate surveys move forward despite current circumstances brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, they posit that shifts in higher education (such as distance learning and telework) heighten the importance of measuring and addressing sexual harassment. In doing so, they suggest the following adaptations:

- Create a communication strategy that is compassionate, acknowledges ongoing challenges, and emphasizes the institution’s commitment to safety and equity,

- Adjust the amount of time that participants are given to respond, providing them with additional flexibility,

- Include questions that ask about sexual harassment experienced in virtual spaces,

- Clarify the window of time during which participants are being asked to recall their experiences (such as before, during, and/or after a switch to remote work/learning), and

- Consider including additional instruments that ask about the impact of COVID-19 on participants’ wellbeing (NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, 2020) (see “Approaches for Collecting Additional Information” section below).

For additional information, including suggested language for survey invitations, see guidance from Holland et al. (2020).

Approaches for Collecting Additional Information

Your team may want to use additional measures and qualitative assessments to get a clearer picture of the overall systems, climates, and cultures that have enabled sexual harassment to thrive. In addition to survey questions about participants’ experiences with sexual harassment, including additional “correlate” questions can provide insight into the historical, structural, and the feelings of your community around the institution’s engagement with this issue (Box 5). Data from correlate survey instruments may also provide the opportunity to monitor whether specific initiatives are having a measurable impact. Collecting such information may help identify campus-level factors that can be targeted to strengthen response and prevention efforts (Moylan et al., 2021).

In addition to or instead of correlate survey instruments, qualitative assessments such as interviews, case studies, focus groups, exit interviews, and sociolegal methods (Moylan et al., 2021; NASEM, 2018) can be used to better understand the ways that sexual harassment is experienced within your organization. Importantly, and as previously noted, qualitative assessments are not a substitute for climate surveys and will not be able to provide prevalence numbers. Though climate surveys can be used to measure the climate of the whole institution and within specific schools or facilities, data acquired through qualitative approaches can complement and build on the knowledge gained from a large-scale climate survey (Driver-Linn and Svensen, 2017; Patton, 2015).

Additionally, in small organizations or units in which it would not be possible to ensure anonymity for climate survey participants, qualitative research methods can be used to understand how sexual harassment is being experienced. Qualitative approaches may prove useful in providing key background information and highlighting both the experiences and perceptions of those who have experienced sexual harassment (Moylan et al., 2021; Swartout et al., 2020). Although not the primary focus of this guidance document, it is very important that if your team chooses to engage in qualitative assessments, subject matter and qualitative experts are consulted.

BOX 5

Using Correlate Survey Instruments to Understand Community Perception

When an individual perceives that their organization tolerates sexual harassment, they are more reluctant to report (Hulin et al., 1996; Offermann and Malamut, 2002) and have worse outcomes (Settles et al., 2006; Sojo et al., 2016). To identify concrete opportunities to change this perception, the institution might want to collect data around the community’s perceptions of and experiences with the institution’s response to sexual harassment when it occurs. To do so, one or both of the following correlate instruments could be used:

- The Institutional Betrayal Questionnaire, a module in the ARC3 survey that measures wrongdoings perpetrated by an institution upon individuals dependent on that institution (termed institutional betrayal (Rosenthal et al., 2016; Smith and Freyd, 2014).

- The Organizational Tolerance of Sexual Harassment Inventory, which “measures the extent to which survey participants perceive that sexually harassing behavior will be associated with negative consequences in their organization” (Hulin et al., 1996).

Analyzing the Data Collected

Once your team has administered your climate survey and collected the data, you must embark on the task of analyzing the information that you have collected and executing your plan for making the best use of it. Examine the data both within and across groups, such as race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, and other relevant demographics, which will reveal patterns in the sexual harassment experiences of specific subpopulations in your community. Separate the prevalence rate across gender identities, as cisgender women, transgender people, and nonbinary people experience higher rates of sexual harassment than cisgender men; a combined prevalence rate will mask these critical distinctions (Kabat-Farr and Cortina, 2014; Magley et al., 1999; Reason and Rankin, 2006; Richey et al., 2019). If possible, examine the data by identity of the perpetrator (peer or individual with power; same race vs. different race, etc.); this is because the impact is very different and because those with more power are creating a kind of institutional and/or cultural betrayal (Bent-Goodley, 2001; Bryant-Davis et al., 2009; Gómez, 2015, 2019a, 2019b; Rosenthal et al., 2016). Finally, your team should consider other meaningful distinctions relevant to the organization, such as graduate or undergraduate; full-time or part-time; taking/teaching classes on campus or taking classes online (or a mix of both); domestic students, international students, and/or students studying abroad; first generation status; etc. Analyzing your data in this way may prove useful in determining correlates, antecedents, outcomes, and factors that attenuate or amplify outcomes of sexual harassment. Identifying these patterns, while still protecting the privacy of the participant, can be helpful in interpreting the results and determining the best way to take action.

Prioritizing Transparency when Interpreting and Sharing Results

Once the data have been analyzed and the results of the survey are presented, your team may feel discouraged by the high prevalence rates that the data have revealed. Best available analysis to date

suggests that organizations can expect at least 50 percent of women faculty and staff to have experienced sexual harassment (Ilies et al., 2003), and 20 to 50 percent of women students to have encountered or experienced sexual harassing conduct in academia (NASEM, 2018; Rosenthal et al., 2016). These rates of sexual harassment are likely even higher among sexual and gender minorities and women of color (Clancy et al., 2017).

At this stage, it is important that your team does not compare its data to that of other organizations that use different surveys. Making direct comparisons of data across organizations is difficult because many surveys do not use a standardized method for measuring or defining sexual harassment, resulting in unreliable prevalence numbers (Moylan et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2017). To put your organization’s prevalence numbers in context, examine survey results at organizations using the same survey methods for measuring prevalence (Box 2), being attentive to subtle differences in methodology.

Choosing to be transparent with and accountable to your community by sharing the results of a prevalence assessment is an important step toward preventing and addressing sexual harassment (NASEM, 2018) but ought to be executed with care (see Boxes 6 and 7). An increasingly common and low-risk way of being transparent with climate assessment results is by providing summaries of the results to the public, or at the very least to those in the organization; for example, see executive reports and summaries shared by the University of Texas System3 and Tulane University.4 Such an action helps demonstrate to the campus community that the institution takes the issue seriously, creates greater transparency about data, policies, and processes, and increases accountability for working to reduce sexual harassment (Freyd, 2018).

BOX 6

Institutional Example: Setting Expectations around Climate Survey Results

After administering a campus climate survey, Carnegie Mellon University presented the results at town hall events open to faculty, staff, and undergraduate and graduate students. During these events, the institution found that different groups displayed a wide range of knowledge about sexual misconduct and a wide spectrum of expectations surrounding the purpose of the climate survey data sharing. Some expressed support for the value of the information sharing. Others hoped that the survey data could be used to frame a starting point for community conversations about sexual misconduct on campus. Still others expected the results to be presented along with fully formed action plans from the university. All of these expectations are reasonable, but they can create dissonance within the forums, leading to confusion and concern for the participants. Thus, when planning presentations about climate survey results, institutions may want to clearly state the objective of the event and consider hosting multiple events with different goals so that all constituencies have an opportunity to engage in the manner most important to them.

___________________

3 See https://www.utsystem.edu/sites/default/files/sites/clase/files/2017-10/academic-aggregate-R11-V4.pdf

4 See https://allin.tulane.edu/sites/allin.tulane.edu/files/WaveofChangeExecutiveReportActionPlan.pdf

BOX 7

How Can an Organization Increase Community Trust in the Climate Survey Process?

When sharing the results of a climate survey, organizational leadership may have a real (or at minimum, a perceived) conflict of interest, including pressure to minimize “bad news.” To help build community trust in the climate survey process, and therefore the results that the survey reveal, institutional betrayal researcher Dr. Jennifer Freyd recommends having someone other than an administrator within the organization be in charge of data analysis and reporting the findings to the community. “Having surveys conducted by researchers whose implicit and explicit incentive is seen as doing ‘good science’ to uncover the facts, and to do replicable work,” shares Dr. Freyd, “may increase the community’s trust in the confidentiality of the survey and the results of the survey.”

Another way that organizations can be courageous is through the way its leaders communicate the results.5 Because the results will likely require the organization to acknowledge that sexual harassment exists within the community and that it needs to be addressed, this is a valuable opportunity for leaders to bear witness, take responsibility for mistakes, and apologize when appropriate. To acknowledge the harm that has taken place and to demonstrate the desire to make changes, the institution could create ways for individuals to share and discuss what happened to them (Box 6) (Freyd, 2018). Finally, when experiences with sexual harassment surface, regardless of when they occurred, conveying that those who speak up about sexual harassment are helpful to the institution can help remediate the harm.

Although this can be done through incentives like awards and salary boosts (Freyd and Birrell, 2013), public acknowledgment and appreciation—such as a press release articulating how the truth teller helped the institution in addressing the problem, or involving the truth teller in a consulting capacity to inform the institution’s plans to address sexual harassment—can make a significant and meaningful difference (Box 8) (Kingkade, 2016).

Taking Action

Once the results of the survey have been communicated to your community, the final task for your climate assessment team is to use the results to inform appropriate interventions. Analyzing contextual factors and collecting relevant information prior to launching an intervention enables an institution to identify and better meet the needs of the community, thus helping to predict expectations, barriers, and readiness around that intervention (King et al., 2010; Roberson et al., 2003). For example, if your climate survey revealed high rates of sexual harassment but low rates of formal reporting, then your team should consider interventions to improve reporting mechanisms (e.g., raising awareness of sexual harassment, increasing trust and reducing risk of institutional betrayal, educating about reporting mechanisms, assessing the efficacy of reporting mechanisms, etc.). If the survey results indicate a need for training to fill knowledge gaps that the community might have about sexual harassment, your team could consider ways in which existing training could be tailored to describe aggregate results from the climate survey itself, including incidence of harassment and correlates of such experiences (e.g., decreased engagement). If your climate survey implicates hiring and promotion

___________________

5 For more information, see Use Science as Tool on Campus Sexual Assault at https://dynamic.uoregon.edu/jjf/articles/freyd2014sciencecampus.pdf

BOX 8

Institutional Example: Apologies and Restorative Justice in Action

Twenty-five years after leaving a Ph.D. program because of sexual harassment by her dissertation advisor, Lisa Schubert contacted the University of Washington to learn more about how the institution had made progress toward protecting students from harassment. The apologies from the university and conversations that ensued led to a new form of collaborative, restorative justice that created a pathway for Schubert to complete her doctorate. The university also invited Schubert to participate in efforts to do away with nondisclosure agreements and address harassment in employment practices. For more information, see www.chronicle.com/article/a-degree-of-justice.

practices, you might consider possible interventions that address that area. For example, are adequate resources available to educate selection/search committees on hiring biases? Do high-level promotions include consideration of vetting personnel records for instances of unprofessional conduct? Do performance evaluations take into account reports of sexual harassment involving the employee? Are adequate resources available to train supervisors on handling conflict? Although there is much left to learn about whether specific prevention efforts are effective in achieving their goals (Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016; NASEM, 2018), taking targeted, tailored action based on the results of the climate survey will demonstrate to the community that the information they have shared will be put to good use, communicating in turn a desire to learn and improve the organization’s climate.

Conclusion

Climate surveys are a valuable tool for organizations needing data on the prevalence of sexual harassment, the ways in which it manifests within their specific communities, and the factors that allow it to persist. Following the guidance outlined in this document and committing the resources necessary will help organizations use scientifically informed tools, involve a diverse set of stakeholders and subject matter experts, analyze results with care, and share the results transparently and courageously. Equipped with the research and specific considerations outlined in this guide, your climate survey team will be well positioned to take a scientific approach to evaluating sexual harassment prevalence. By measuring how and where sexual harassment is occurring, your organization can then develop well-informed action plans that will lead to more effective strategies for preventing and addressing sexual harassment, and, most importantly, a safer and healthier environment for your community.

References

1. Administrator Researcher Campus Climate Collaborative 2015. ARC3 campus climate survey. https://campusclimate.gsu.edu/arc3-campus-climate-survey/ (accessed 25 February 2021).

2. Allen, N. E. 2005. A multi-level analysis of community coordinating councils. American Journal of Community Psychology 35(1-2):49-63.

3. Banyard, V. L. 2014. Improving college campus-based prevention of violence against women: A strategic plan for research built on multipronged practices and policies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 15(4):339-351.

4. Basile, K. C., M. J. Breiding, and S. G. Smith. 2016. Disability and risk of recent sexual violence in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 106(5):928-933.

5. Becker-Blease, K. A., and J. J. Freyd. 2007. The ethics of asking about abuse and the harm of “don’t ask, don’t tell.” American Psychologist, 62(4), 330–332.

6. Bent-Goodley, T. B. 2001. Eradicating domestic violence in the African American community: A literature review and action agenda. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2(4):316-330.

7. Bryant-Davis, T., H. Chung, and S. Tillman. 2009. From the margins to the center: Ethnic minority women and the mental health effects of sexual assault. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 10(4):330-357.

8. Bumiller, K. 1987. Victims in the shadow of the law: A critique of the model of legal protection. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 12(3):421-439.

9. Bumiller, K. 1992. The civil rights society: The social construction of victims: JHU Press.

10. Cialdini, R. 1984. Influence: The psychology of persuasion. William Morrow and Company, Inc.

11. Clancy, K. B., K. M. Lee, E. M. Rodgers, and C. Richey. 2017. Double jeopardy in astronomy and planetary science: Women of color face greater risks of gendered and racial harassment. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 122(7):1610-1623.

12. Colquitt, J. A., B. A. Scott, J. B. Rodell, D. M. Long, C. P. Zapata, D. E. Conlon, and M. J. Wesson. 2013. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology 98(2):199.

13. Cortina, L. M. 2004. Hispanic perspectives on sexual harassment and social support. Personal and Social Psychology Bulletin 30(5):570-584.

14. Cortina, L. M., and J. L. Berdahl. 2008. Sexual harassment in organizations: A decade of research in review. Handbook of Organizational Behavior 1:469-497.

15. Cortina, L. M., S. Swan, L. F. Fitzgerald, and C. Waldo. 1998. Sexual harassment and assault: Chilling the climate for women in academia. Psychology of Women Quarterly 22(3):419-441.

16. Cuomo, A. 2015. Complying with Education Law Article 129-B, edited by New York State Education Department and New York State Office of Campus Safety.

17. Dillman, D. A., J. D. Smyth, and L. M. Christian. 2014. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method: John Wiley & Sons.

18. Driver-Linn, E., and L. Svensen. 2017. Moving Toward a “Data Ecosystem” to Assess Campus Responses to Sexual Assault and Misconduct. Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/key-issues/moving-toward-data-ecosystem-assess-campus-responses-sexual-assault-and-misconduct (accessed 22 September 2021).

19. Edwards, V. J., S. R. Dube, V. J. Felitti, and R. F. Anda. 2007. It’s ok to ask about past abuse. American Psychologist 62(4), 327–328.

20. Farley, L. 1978. Sexual shakedown: The sexual harassment of women on the job: New York: McGraw-Hill.

21. Feldblum, C. R., and V. A. Lipnic. 2016. Select task force on the study of harassment in the workplace. Washington: US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

22. Fitzgerald, L. F., M. J. Gelfand, and F. Drasgow. 1995. Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 17(4):425-445.

23. Flack Jr, W. F., M. L. Caron, S. J. Leinen, K. G. Breitenbach, A. M. Barber, E. N. Brown, C. T. Gilbert, T. F. Harchak, M. M. Hendricks, and C. E. Rector. 2008. “The red zone” temporal risk for unwanted sex among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23(9):1177-1196.

24. Flack, W. F., K. Swartout, and K. J. Holland. 2019. Assessing faculty and staff experiences and perceptions of sexual misconduct. Paper presented at Faculty and Staff Sexual Misconduct Conference, Madison, WI.

25. Freyd, J. 2014. Official campus statistics for sexual violence mislead. http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/7/college-campus-sexualassaultsafetydatawhitehousegender.html#commentsDiv (accessed 25 February 2021).

26. Freyd, J. 2018. When sexual assault victims speak out, their institutions often betray them. https://theconversation.com/when-sexual-assault-victims-speak-out-their-institutions-often-betray-them-87050 (accessed 25 February 2021).

27. Freyd, J., and P. Birrell. 2013. Blind to betrayal: Why we fool ourselves we aren’t being fooled: John Wiley & Sons.

28. Glomb, T. M., W. L. Richman, C. L. Hulin, F. Drasgow, K. T. Schneider, and L. F. Fitzgerald. 1997. Ambient sexual harassment: An integrated model of antecedents and consequences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 71(3):309-328.

29. Gómez, J. 2015. Rape, black men, and the degraded black woman: Feminist psychologists’ role in addressing within-group sexual violence. The Feminist Psychologist: Newsletter for the Society of the Psychology of Women (American Psychological Association Division 35) 42(2):12-13.

30. Gómez, J. M. 2019a. Isn’t it all about victimization?(intra)cultural pressure and cutural betrayal trauma in ethnic minority college women. Violence against women 25(10):1211-1225.

31. Gómez, J. M. 2019b. What’s in a betrayal? Trauma, dissociation, and hallucinations among high-functioning ethnic minority emerging adults. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 28(10):1181-1198.

32. Gómez, J. M., M. Rosenthal, C. Smith, and J. J. Freyd. 2015. Participant reactions to questions about gender-based sexual violence: Implications for campus climate surveys. Ejournal of Public Affairs: Special Issue on Higher Education’s Role on Preventing and Responding to Gender-Based Violence 4:39-71.

33. Grady, C. 2020. Why the term “BIPOC” is so complicated, explained by linguists.

34. Greco, L. M., E. H. O’Boyle, and S. L. Walter. 2015. Absence of malice: A meta-analysis of nonresponse bias in counterproductive work behavior research. Journal of Applied Psychology 100(1):75.

35. Groves, R. M., R. B. Cialdini, and M. P. Couper. 1992. Understanding the decision to participate in a survey. Public Opinion Quarterly 56(4):475-495.

36. Holland, K. J., and L. M. Cortina. 2013. When sexism and feminism collide: The sexual harassment of feminist working women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 37(2):192-208.

37. Holland, K. J., V. C. Rabelo, and L. M. Cortina. 2014. Sexual assault training in the military: Evaluating efforts to end the “invisible war”. American Journal of Community Psychology 54(3-4):289-303.

38. Holland, K. J., V. C. Rabelo, A. M. Gustafson, R. C. Seabrook, and L. M. Cortina. 2016. Sexual harassment against men: Examining the roles of feminist activism, sexuality, and organizational context. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 17(1):17.

39. Holland, K. J., L. M. Cortina, V. J. Magley, A. L. Baker, and F. F. Benya. 2020. Don’t let COVID-19 disrupt campus climate surveys of sexual harassment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(40): 24606-24608.

40. Hulin, C. L., L. F. Fitzgerald, and F. Drasgow. 1996. Organizational influences on sexual harassment: Sage Publications, Inc.

41. ICF Next. 2020. NIH workplace climate and harassment survey: Survey development and methods report. https://diversity.nih.gov/sites/coswd/files/images/docs/NIH_Workplace_Climate_and_Harassment_Survey_Development_and_Methods_508.pdf (accessed 25 February 2021).

42. Ilies, R., N. Hauserman, S. Schwochau, and J. Stibal. 2003. Reported incidence rates of work-related sexual harassment in the United States: Using meta-analysis to explain reported rate disparities. Personnel Psychology 56(3):607-631.

43. Jaffe, A. E., D. DiLillo, L. Hoffman, M. Haikalis, and R. E. Dykstra. 2015. Does it hurt to ask? A meta-analysis of participant reactions to trauma research. Clinical Psychology Review 40:40-56.

44. Kabat-Farr, D., and L. M. Cortina. 2014. Sex-based harassment in employment: New insights

into gender and context. Law and Human Behavior 38(1):58.

45. King, E. B., L. M. Gulick, and D. R. Avery. 2010. The divide between diversity training and diversity education: Integrating best practices. Journal of Management Education 34(6):891-906.

46. Kingkade, T. 2016. What it looks like when a university truly fixes how it handles sexual assault. HuffPost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/oregon-state-university-sexual-assault_n_56f-426c3e4b02c402f66c3b9.

47. Konik, J., and L. M. Cortina. 2008. Policing gender at work: Intersections of harassment based on sex and sexuality. Social Justice Research 21(3):313-337.

48. Krosnick, J. A., S. Presser, K. H. Fealing, S. Ruggles, and D. L. Vannette. 2015. The future of survey research: Challenges and opportunities. The National Science Foundation Advisory Committee for the Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences Subcommittee on Advancing SBE Survey Research:1-15.

49. Langhout, R. D., M. E. Bergman, L. M. Cortina, L. F. Fitzgerald, F. Drasgow, and J. H. Williams. 2005. Sexual harassment severity: Assessing situational and personal determinants and outcomes 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 35(5):975-1007.

50. Leskinen, E. A., L. M. Cortina, and D. B. Kabat. 2011. Gender harassment: Broadening our understanding of sex-based harassment at work. Law and Human Behavior 35(1):25-39.

51. Lichty, L. F., R. Campbell, and J. Schuiteman. 2008. Developing a university-wide institutional response to sexual assault and relationship violence. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 36(1-2):5-22.

52. Lind, E. A., R. Kanfer, and P. C. Earley. 1990. Voice, control, and procedural justice: Instrumental and noninstrumental concerns in fairness judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59(5):952.

53. Lombardi, E. L., R. A. Wilchins, D. Priesing, and D. Malouf. 2002. Gender violence: Transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. Journal of Homosexuality 42(1):89-101.

54. MacKinnon, C. A. 1979. Sexual harassment of working women: A case of sex discrimination: Yale University Press.

55. Magley, V. J., C. R. Waldo, F. Drasgow, and L. F. Fitzgerald. 1999. The impact of sexual harassment on military personnel: Is it the same for men and women? Military Psychology 11(3):283-302.

56. McMahon, S., K. Stepleton, and J. Cusano. 2014. Understanding and responding to campus sexual assault: A guide to climate assessment for colleges and universities. Center on Violence Against Women and Children: Rutgers School of Social Work.

57. McMahon, S., K. Stepleton, and J. Cusano. 2016. Understanding and responding to campus sexual assault: A guide to climate assessment for colleges and universities. Center on Violence Against Women and Children: Rutgers School of Social Work.

58. Meyer, I. H., and P. A. Wilson. 2009. Sampling lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology 56(1):23.

59. Moylan, C. A., C. Hatfield, and J. Randall. 2018. Campus sexual assault climate surveys: A brief exploration of publicly available reports. Journal of American College Health 66(6):445-449.

60. Moylan, C. A., M. Javorka, M. K. Maas, E. Meier, and H. L. McCauley. 2021. Campus sexual assault climate: Toward an expanded definition and improved assessment. Psychology of Violence 11(3): 296-306.

61. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2018. Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

62. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Promising Practices for Addressing the Underrepresentation of Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Opening Doors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

63. NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. 2020. COVID-19 OBSSR research tools. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/dr2/COVID-19_BSSR_Research_Tools.pdf (accessed 8 August 2020).

64. Offermann, L. R., and A. B. Malamut. 2002. When leaders harass: The impact of target perceptions of organizational leadership and

climate on harassment reporting and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology 87(5):885.

65. Parker, K. H. B. 2008. Ambient harassment under Title VII: Reconsidering the workplace environment. Northwestern University Law Review 102:945.

66. Patton, M. Q. 2015. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications.

67. Pérez, E. 2020. “People of Color” Are Protesting. Here’s What You Need to Know about This New Identity. Washington Post, July 2, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/07/02/people-color-are-protesting-heres-what-you-need-know-about-this-new-identity/.

68. Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, J.-Y. Lee, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88(5):879.

69. Quijano, A. 2019. Established campus sexual assault commission, edited by State of New Jersey.

70. Reason, R. D., and S. R. Rankin. 2006. College students’ experiences and perceptions of harassment on campus: An exploration of gender differences. College Student Affairs Journal 26(1):7-29.

71. Richey, C. R., K. Lee, E. Rodgers, and K. B. Clancy. 2019. Gender and sexual minorities in astronomy and planetary science face increased risks of harassment and assault. Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 51(4).

72. Roberson, L., C. T. Kulik, and M. B. Pepper. 2003. Using needs assessment to resolve controversies in diversity training design. Group & Organization Management 28(1):148-174.

73. Rosenthal, M. N., A. M. Smidt, and J. J. Freyd. 2016. Still second class: Sexual harassment of graduate students. Psychology of Women Quarterly 40(3):364-377.

74. Sable, M. R., F. Danis, D. L. Mauzy, and S. K. Gallagher. 2006. Barriers to reporting sexual assault for women and men: Perspectives of college students. Journal of American College Health 55(3):157-162.

75. Schilt, K. 2010. Just one of the guys?: Transgender men and the persistence of gender inequality: University of Chicago Press.

76. Schilt, K., and C. Connell. 2007. Do workplace gender transitions make gender trouble? Gender, Work & Organization 14(6):596-618.

77. Schneider, K. T., S. Swan, and L. F. Fitzgerald. 1997. Job-related and psychological effects of sexual harassment in the workplace: Empirical evidence from two organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology 82(3):401.

78. Settles, I. H., L. M. Cortina, J. Malley, and A. J. Stewart. 2006. The climate for women in academic science: The good, the bad, and the changeable. Psychology of Women Quarterly 30(1):47-58.

79. Settles, I. H., J. S. Pratt-Hyatt, and N. T. Buchanan. 2008. Through the lens of race: Black and white women’s perceptions of womanhood. Psychology of Women Quarterly 32(4):454-468.

80. Smith, C. P., and J. J. Freyd. 2014. Institutional betrayal. American Psychologist 69(6):575.

81. Sojo, V. E., R. E. Wood, and A. E. Genat. 2016. Harmful workplace experiences and women’s occupational well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly 40(1):10-40.

82. Stark, S., O. S. Chernyshenko, A. R. Lancaster, F. Drasgow, and L. F. Fitzgerald. 2002. Toward standardized measurement of sexual harassment: Shortening the SEQ-DOD using item response theory. Military Psychology 14(1):49-72.

83. Stith, S., I. Pruitt, J. Dees, M. Fronce, N. Green, A. Som, and D. Linkh. 2006. Implementing community-based prevention programming: A review of the literature. Journal of Primary Prevention 27(6):599-617.

84. Swartout, K. M., W. F. Flack Jr, S. L. Cook, L. N. Olson, P. H. Smith, and J. W. White. 2019. Measuring campus sexual misconduct and its context: The Administrator Researcher Campus Climate Consortium (ARC3) survey. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 11(5):495.

85. Swartout, K. M., L. Wood, and N. Busch-Armendariz. 2020. Responding to campus climate data: Developing an action plan to reduce campus sexual misconduct. Health Education & Behavior 47(1 Supple):70S-74S.

86. USEEOC. 1980. Guidelines on discrimination because of sex. In C.F.R. Title 29 Subtitle B, Chapter XIV Part 1604, edited by USEEO C.

87. Vargas, E. A., S. T. Brassel, L. M. Cortina, I. H. Settles, T. R. Johnson, and R. Jagsi. 2020. #medtoo: A large-scale examination of the incidence and impact of sexual harassment of physicians and other faculty at an academic medical center. Journal of Women’s Health 29(1):13-20.

88. Wasti, S. A., and L. M. Cortina. 2002. Coping in context: Sociocultural determinants of responses to sexual harassment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83(2):394.

89. WHO. 2001. Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. World Health Organization.

90. Wood, L., C. Sulley, M. Kammer-Kerwick, D. Follingstad, and N. Busch-Armendariz. 2017. Climate surveys: An inventory of understanding sexual assault and other crimes of interpersonal violence at institutions of higher education. Violence Against Women 23(10):1249-1267.

DOI

https://doi.org/10.17226/26346

Suggested Citation

Merhill, N. M., K. A. Bonner, and A. L. Baker (Eds.). 2021. Guidance for Measuring Sexual Harassment Prevalence Using Campus Climate Surveys. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.7226/26346.

Author Information

The authors of this guidance document are institutional representatives to the Evaluation Working Group of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education. In creating this document, this Evaluation Working Group was co-led by Nicole Merhill, Director of the Office for Gender Equity and University Title IX Coordinator at Harvard University, and Chicora Martin, the Vice President of Student Life and Dean of Students at Mills College. Elizabeth Rosemeyer is the Title IX Coordinator and Director of the Office of Title IX Initiatives at Carnegie Mellon University. Cynthia Herrington is an Associate Professor of Surgery at the University of Southern California (USC) and Program Director of the Congenital Cardiac Surgery Fellowship at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Brittany Grice is the District Director and Title IX Coordinator of the Los Angeles Community College District (LACCD). Kristofferson Culmer is a PhD candidate at the University of Missouri and the Former Director of External Affairs at the National Association of Graduate-Professional Students. Kelley Bonner is the Director of the Workplace Violence Prevention and Response Office at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Lauren Schoenthaler is Senior University Counsel in the Office of General Counsel at Stanford University. Helen Malone is the Vice Provost for Academic Policy and Faculty Resources at The Ohio State University. Mariam Lam is the Vice Chancellor and Chief Diversity Officer at the University of California, Riverside. In the Office for the Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), Helen Kaiser is the Associate Director and Deputy Title IX Officer. At the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), Ariana Alvarez is the Title IX Officer and Director. Maria Sevilla is the Deputy Title IX Coordinator at the University of Miami. At USC, Catherine Spear is Vice President for Equity, Equal Opportunity, and Title IX and Title IX Coordinator.

Acknowledgments

This Guidance Document was reviewed in draft form by individuals chosen for their diverse perspectives and technical expertise. The purpose of this independent review is to provide candid and critical comments that will assist the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in making each publication as sound as possible and to ensure

that it meets the institutional standards for quality, objectivity, evidence, and responsiveness to the charge. The review comments and draft manuscript remain confidential to protect the integrity of the deliberative process.

We thank the following individuals for their review of this Guidance Document:

Jason Charland, University of Maine; Michele Decker, Johns Hopkins University; Jennifer M. Gómez, Wayne State University; Erick Jones, University of Texas at Arlington; Carrie Moylan, Michigan State University; Meredith Smith, Tulane University; Lily Svensen, Yale University; and Kevin Swartout, Georgia State University.

Although the reviewers listed above provided many constructive comments and suggestions, they were not asked to endorse the Guidance Document nor did they see the final draft before its release. The review of this Guidance Document was overseen by Marilyn Baker, the National Academies, and Carol B. Muller, Stanford University (retired). They were responsible for making certain that an independent examination of this Guidance Document was carried out in accordance with the standards of the National Academies and that all review comments were carefully considered. Responsibility for the final content rests entirely with the authors.

The authors would also like to acknowledge the following former Evaluation Working Group representatives who contributed to this document: Victoria Friedman (District Compliance Officer and Deputy Title IX Coordinator in the Office for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion at LACCD; representative from December 2020 to February 2021), Kathy Lasher (Former Associate Vice President for Institutional Equity at The Ohio State University; representative from June 2019 to November 2020), Beth Grampetro (Director of Wellness at the Olin College of Engineering), Michael Diaz (Director and Title IX Officer in the Office for the Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination at UCSD; representative from January 2020 to May 2020), Carol Genetti (Former Dean of Graduate Division and Professor of Linguistics at UCSB; representative from June 2019 to July 2020), Nancy Lowitt (Former Associate Dean of Faculty Affairs and Professional Development and Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine; representative from June 2019 to March 2020), Kimberly Lumpkins (Associate Professor of Surgery at the University of Maryland School of Medicine; representative from March 2020 to February 2021), Shafiqa Ahmadi (Professor of Clinical Education and the Co-Director for the Rossier School of Education’s Center for Education, Identity and Social Justice at USC; representative from June 2019 to December 2020), and Kate Upatham (Director of Nondiscrimination Initiatives and Title IX Coordinator at Wellesley College; representative from January 2020 to December 2020). The authors would like to acknowledge Lilia Cortina, Jennifer Freyd, Kathryn Holland, and Vicki Magley, members of the Action Collaborative’s Advisory Group, for their valuable contributions to this paper. The authors would also like to thank Arielle Baker, Program Officer; Frazier Benya, Senior Program Officer; and Imani Braxton-Allen, Senior Program Assistant at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for the valuable support they provided for this paper.

About the Action Collaborative

The Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education brings together academic and research institutions and key stakeholders to work toward targeted, collective action on addressing and preventing sexual harassment across all disciplines and among all people in higher education. The Members actively collaborate to identify, research, develop, and implement efforts that move beyond basic legal compliance to evidence-based

policies and practices for addressing and preventing all forms of sexual harassment and promoting a campus climate of civility and respect. The Action Collaborative includes four Working Groups (Prevention, Response, Remediation, and Evaluation) that compile and gather information, and publish resources for the higher education community. The Evaluation Working Group focuses on measuring climate and gauging progress on campuses.

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures

None disclosed.

Correspondence

Questions or comments should be directed to Arielle Baker at abaker@nas.edu.