Educational Pathways for Black Students in Science, Engineering, and Medicine: Exploring Barriers and Possible Interventions: Proceedings of a Workshop (2022)

Chapter: 2 Background and What Is Missing in Key Milestones and Existing Pathway Programs

Planning committee co-chair Lynne Holden, M.D., introduced the first panel: Shirley Malcom, Ph.D., American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS); Louis Sullivan, M.D., Sullivan Alliance; Roderic Pettigrew, Ph.D., M.D., Texas A&M University; and Marc Nivet, Ed.D., M.B.A., University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. The presenters provided background for the rest of the workshop, including key milestones missed by many Black children, why missing these milestones deters progress along the pathway, and ideas to rectify the status quo.

A LOOK ACROSS THE LIFE CYCLE

Dr. Malcom said she saw her role as the workshop’s first presenter to introduce a life-cycle approach to identify missed milestones and broken pathways for young people. At each stage from birth to adulthood, she noted, young people are confronted with problems/barriers, opportunities, and variables. She defined “variables” as events that could result in a problem or an opportunity, depending on how it manifests itself (e.g., the relative quality of an early childhood setting). She explained that a life-cycle approach looks at an intertwined ecosystem of inequities in education, health, and environment, and she stated:

The time is critical. The world is changing, and I am concerned that Black men and women are not having the opportunity to shape what that future will look like. Unless we consider what happens in regard to education, we are not going to understand where the opportunities are or where are the barriers that must be removed.

Starting with a child’s earliest years, family concerns about food and housing insecurity, the exposome (collection of environmental factors), and poverty have a bearing on future trajectories. Black babies are dispro-

portionately born with higher levels of lead in their systems, which can have cognitive and behavioral effects, and their mothers often have less access to prenatal care.

Access to early care and education is a critical milestone. Participation in quality programs provides an opportunity; a variable, as Dr. Malcom defined it, is the availability of such programs. Children have greater or lesser opportunity to speak in family and early education settings, which affects their preparation to read when they reach kindergarten. Some children have the advantage of dual-language learning within their households, but no matter the situation, “The question of being ready to learn is absolutely a critical milestone,” she stressed.

In K–3, children move from “learning to read” to “reading to learn” by grade 4. Culturally responsive, equitable teaching strategies and classroom practices help students achieve this important milestone, she said. Throughout the school years, teacher diversity, teacher quality, school and student diversity, and school quality and resources are critical in whether students reach the grade 4 reading milestone or not. A current barrier for many Black students, with in-person schooling curtailed because of COVID-19, is adequacy of technology and access to high-speed internet.

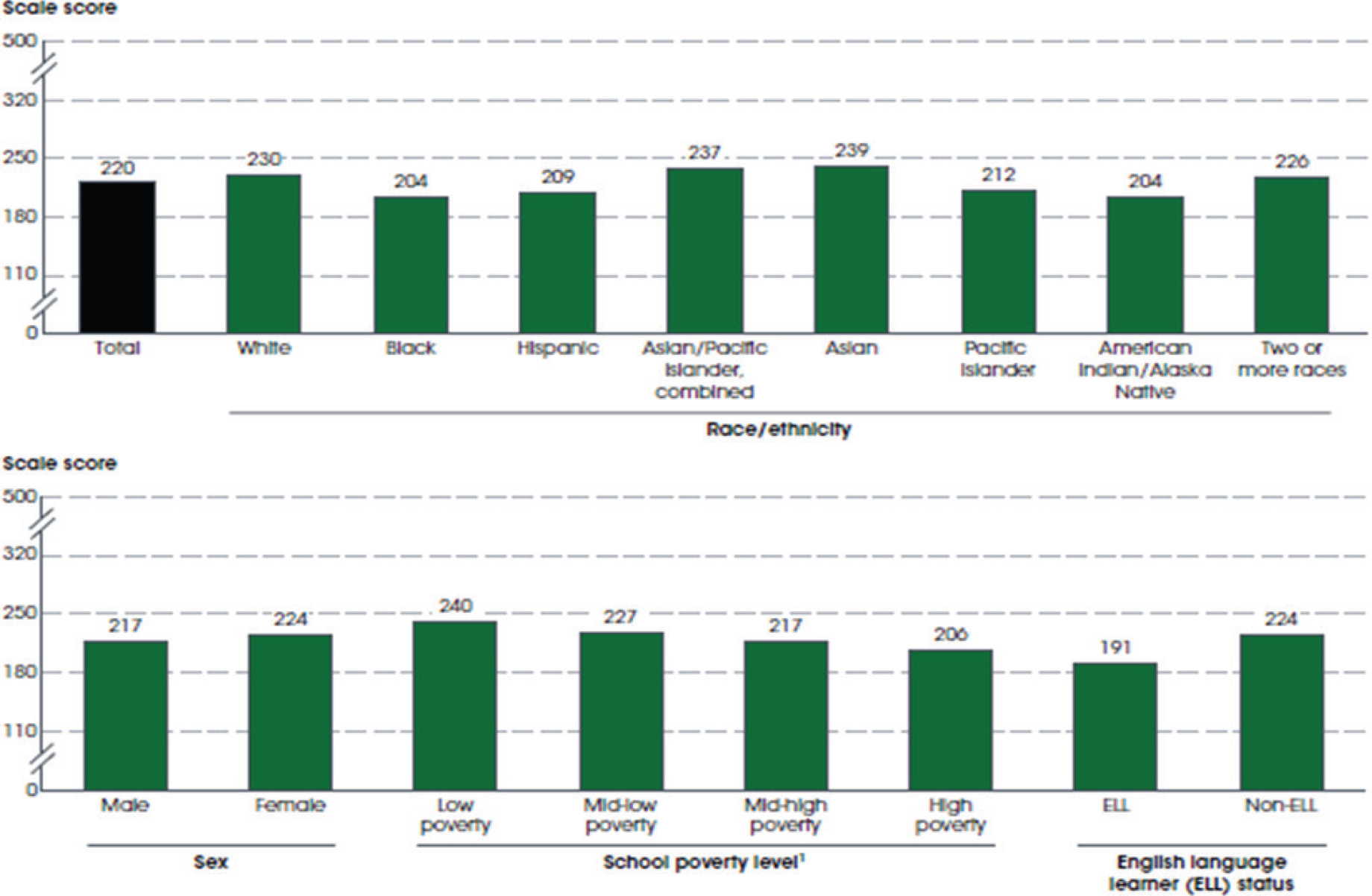

Looking at grade 4 reading and math scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress from 1992 to 2019, Dr. Malcom called attention to slight improvements by Black students, but a persistent gap between Black and other, particularly white and Asian, students. The gaps are not closing, she pointed out, and they are tied to school poverty levels (see Figure 2-1).

A critical milestone in preparedness for STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine) centers on whether a student has taken algebra by grade 8. Many Black students do not take advanced math in middle school. Even when algebra is offered to students in higher-poverty middle schools, a recent article called out that “separate algebra is unequal algebra” (Sparks, 2020). In other words, she explained, based on research by the American Educational Research Association, algebra in higher-poverty middle schools is often not taught in the same depth as at more affluent schools.

In high school, a barrier for many Black students is lack of access to Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate, and other rigorous courses in physics, calculus, and chemistry. Opportunities around this barrier include the College Readiness Program run by the National Math and Science Initiative (for which she is board chair) and many enrichment

SOURCE: Shirley Malcom, Workshop Presentation, September 2, 2020, from NAEP data.

programs, such as those offered by Mentoring in Medicine, Project SEED, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. However, they are not sufficient to reach the majority of students. A lack of diversity among STEMM teachers and differing teacher expectations of students based on their race also affect access to rigorous coursework. Important variables include access to places of science (such as labs and science centers) and internet access.

When it is time to consider higher education, it matters which institution a student chooses, Dr. Malcom said. Although Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) serve a very small percentage of the overall student population, they have an outsized role in Black students’ degree attainment: 20 percent of Black students who complete bachelor’s degrees and 27 percent of Black students with STEMM degrees earn their degrees at HBCUs.

Standardized test differentials have been a major barrier to access quality programs. She commented that COVID-19 has led a number of institutions to reduce their reliance on SAT and ACT scores, which may serve as a natural experiment about the impact of these tests as gatekeepers. Further, legal challenges to programs that consider race in admission to elite institutions are a barrier to the advancement of many qualified Black students. The availability of grants and loans and time to degree are variables that affect successful completion—the longer an education takes, the more it costs, and many students do not have the financial means to remain in or to return to college.

Across races and ethnicities, students express similar levels of interest in STEM subjects, according to data from the Higher Education Research Institute. However, and as discussed by other workshop presenters, more Black than white students move out of STEM majors. Recent research (Seymour and Hunter, 2019) has looked at why students are not staying in STEM. Challenges identified include weed-out courses, poor teaching, lack of faculty diversity, and the need for paid employment that takes away from study time. Many students of color with strong interest feel “driven out” of these fields, she commented. Opportunities such as culturally responsive pedagogy and student research opportunities have positive influences on retention and maintaining interest in graduate or medical education. Access to mentors and other support programs are also important.

The transition to graduate and medical education has some predictable barriers, Dr. Malcom said, including the predominance of MCATs (Medical College Admission Tests) and GRE (Graduate Record Examination) scores in admissions decisions. Once students are enrolled, lack of faculty diversity, hyper-competitiveness and lack of community, curriculum, noninclusive

research agendas, and real and perceived costs can prevent successful completion. Opportunities that yield positive effects include professional recognition to present and publish research, as well as networking.

Workforce and workplace concerns start with severe underrepresentation in the STEM workforce. According to National Science Foundation data from 2019, Black women are 6.5 percent of the U.S. population between ages 18 and 64, but only 2.5 percent of the science and engineering workforce. Black men are 5.9 percent of the overall population, ages 18–64, but only 3.1 percent of the science and engineering workforce.

Looking across life-cycle milestones, beginning at birth, Dr. Malcom concluded:1

The bottom line is there is cumulative disadvantage. Trauma exposure and epigenetics, stressors, lower rates of vaccinations, higher levels of expulsions and suspensions, the intersecting areas of bias and even climate change…. [A]ll these things are interconnected.

An example illustrates this interconnectedness. The siting of an industrial plant in or near a Black community affects air quality and asthma. Asthma affects school attendance and possible retention in a grade. Retention in grade reduces the likelihood of school completions. Given such interconnections, she said, the emphasis for action has to go beyond individuals’ characteristics to explain success or its lack. “We focus on the people who make it through personal grit or resilience, but we have to start looking at institutional accountability and the way that institutions provide roadmaps,” she said. “Interventions are important, but they need to be part of a systemic approach. Because systems are the problem, only systemic change can bring lasting solutions.”

Dr. Malcom briefly explained the program she directs at AAAS called SEA Change,2 which “provides the scaffolding to guide and support context-specific, voluntary change within institutions that will result in systemic transformation in STEMM.” Policies, programs, and practices must be changed, she stressed; otherwise, a specific intervention ends when the person who leads it leaves or when the funding stops.

___________________

1 The impact of these stressors may vary for Black communities across the United States.

2 More information available at https://seachange.aaas.org.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF BLACK REPRESENTATION IN U.S. MEDICAL SCHOOLS

Dr. Sullivan called for a more inclusive, effective, diverse health-care workforce, as well as a more supportive health-care system. The country’s inability to achieve these goals, he said, can be explained in part through an overview of the past half-century’s attempts to increase diversity in the medical workforce in the United States. “We have made some progress but far less than what we have hoped and what we had expected,” he stated. However, he added, the combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and increased awareness of civil liberties may have awakened the nation’s conscience in a way that opportunities to improve the system are there. Seizing the opportunity can result in a stronger workforce and the elimination of racial disparities.

In 1950, 80 medical schools in the country graduated some 8,000 physicians a year. Two percent were African American and most graduated from Howard University College of Medicine and Meharry Medical College, Dr. Sullivan explained. No other medical school in the South admitted Black students, except for the University of Arkansas beginning in 1948. In the 1950s and early 1960s, a projected shortage of physicians led to the establishment of 47 new schools and expanded class sizes in the existing schools. The civil rights movement led to integration in medical schools in the South. The last southern schools to admit Black students—Duke and Vanderbilt Universities—did so in 1966. The total number of students increased to more than 16,000, of whom 1,600 were African American. This was a significant increase but far from adequate to diversify the workforce, he said.

In 1968, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) formed its first committee on diversity among medical students, with Dr. Sullivan as a member. A series of studies and initiatives by AAMC and by individual schools followed. In 1978, Morehouse College opened a new medical school, and the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science opened in 1981. In sum, he said, the latter half of the 20th century saw great expectations for improved diversity, thanks to the role of the federal government to expand medical education and the civil rights movement.

However, in the early 1980s, the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee (GMENAC, 1981) issued a report that expressed concern that the expansions would result in a physician surplus. That report led Congress to limit or eliminate programs and support for medical school infrastructure, faculty development, and scholarships and loans. The pre-

vailing philosophy became that physicians and other health professionals are high earners who can pay back their education through future earnings. Reflecting on that change, Dr. Sullivan stated:

That, in my view, was a major error of national policy. It led to what we have today: that is, the large burden of student debt that exists among our nation’s medical students. That directly impacts what we are trying to do to increase diversity in the nation’s healthcare professions.

Today, Dr. Sullivan pointed out, the average income of families of students entering medical schools is much higher than the national average. (For further discussion of the impact of finances on medical school enrollment, see Chapter 5.) The huge debt that would be incurred deters many students from low-income backgrounds from pursuing a career in health-care professions. Many cannot burden themselves or others in their family with these costs.

Efforts to increase diversity have to include financial support to students, stated Dr. Sullivan. He and others of his generation, he noted, faced legally enforced segregation in the South and very few seats in medical schools in other parts of the country. (He was the only Black student in his class at Boston University School of Medicine in 1954, he noted.) “We were in an environment as the exception,” he recalled. “Rigid segregation and quotas were the problems. Now, schools are working to increase diversity in their classes, but the barrier of indebtedness is a major one that has to be considered.”

Dr. Sullivan urged a change in the environment toward recognition that investment in health is a positive investment. The health system is embroiled in politics, he commented, which works to the disadvantage of health. “Health should be seen as a social good, in the same way we look at education,” he said. “Everyone has a right to health, health care, and health information.” He added that economics, in addition to humanitarian concerns, supports this argument, noting, “A healthy population who can enter the workforce, be productive, earn wages, pay taxes, and support families will place less demand on social support systems.” As an example, a study in 2019 (Hendren and Sprung-Keyser, 2019) found that investments in maternal and child care resulted in healthier adults with a better work history and whose earnings amply repaid the amount invested in their health care. He urged working with economists to quantify the overall benefits of health care.

Diversity in the health system is important not only for fairness and equity but also for effectiveness of the system, he concluded. Provision of good health relies on well-trained and well-qualified individuals. It also requires good communication, trust between patient and provider, understanding the life of the patient, and respect. “That is the challenge for all of us trying to improve the health of the entire population,” he said. “[The Roundtable] has a major challenge and a major opportunity. Changes to be effective must have broad public support.”

SEVEN AREAS FOR POSSIBLE INTERVENTIONS

Dr. Pettigrew said he would add his perspective to the comprehensive presentations by Dr. Malcom and Dr. Sullivan with a focus on possible interventions. Based on an assessment of needs, he said he has distilled seven areas to overcome the problem of the nation not taking full advantage of the talent that resides in the Black and Brown communities.

First, he said, is the importance of role models. The challenge is moving beyond a single role model to multiple role models prevalent throughout the system, at every level of the learning experience, from K–12, through undergraduate and graduate education, through the career stage. It is a circular challenge, he acknowledged, in that Black and Brown individuals are needed to serve as role models, but they themselves need role models to reach the levels where they can provide this support. Role models should be visible; he noted in some institutions, people of color are not as celebrated as their majority counterparts. Institutions need to show clearly that people of color are “around the table, in the room” in decision-making capacities. Universities need to embrace this challenge to create a sense of belonging, he said.

Second, critical mass of minority students and faculty is important. Leadership may talk about the need for diversity but seem satisfied with one person from the Black or Brown community on a committee, on the faculty, or in other positions. He stated:

This conscious or subconscious tokenism does not get us where we need to be. We need to have substantial mass to create a supportive environment for students and faculty so they don’t have professional isolation…. Race becomes less apparent when the person is not “the” minority representative. This is an important point that needs to be driven home, especially at majority institutions.

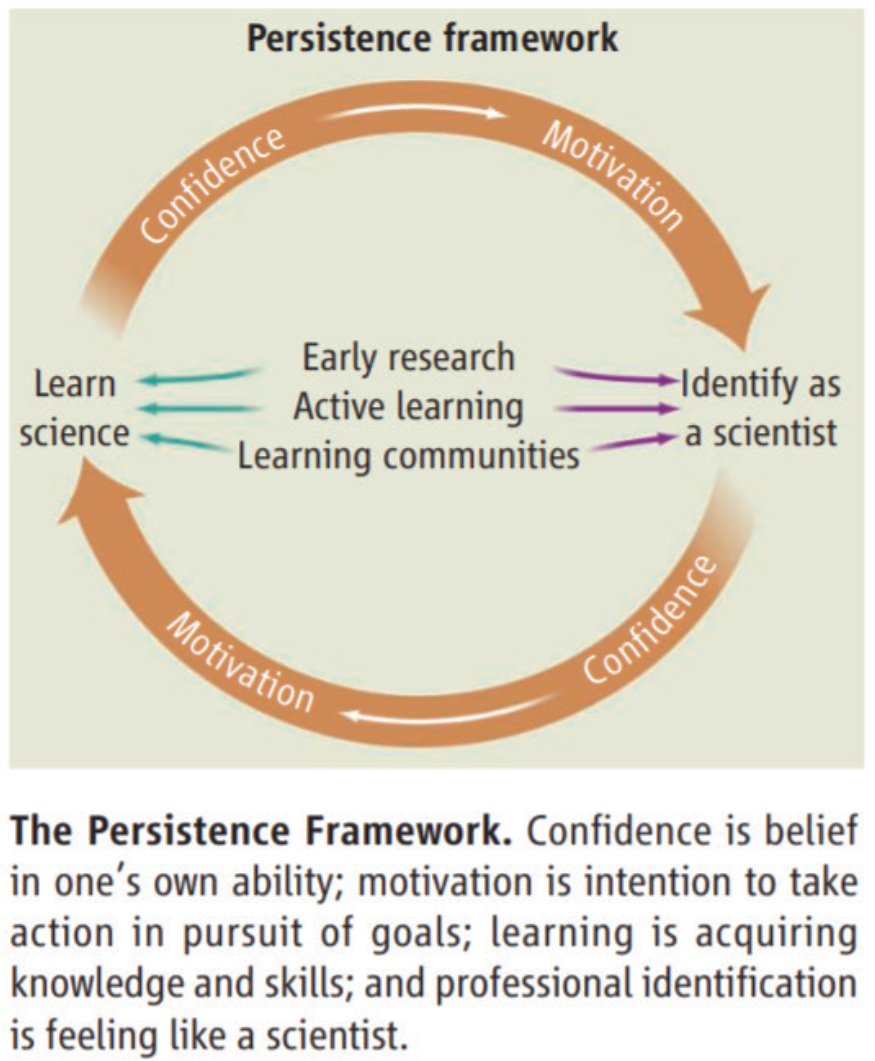

Third, Dr. Pettigrew focused on persistence, which he differentiated from retention. Persistence, he clarified, speaks to student agency and engagement. As Dr. Malcom pointed out (and discussed in Chapter 4), Black and Brown students declare an interest in STEM at about the same percentage (about one-third) as other students, but the number decreases to about one-fifth of bachelor’s degrees and about one-twelfth of Ph.D. degrees earned by minority students. Dr. Pettigrew noted that persistence can be achieved through high expectations, beginning at the earliest levels. Communicating a strong belief in young people’s abilities fosters high expectations, he said, noting it has high yield but must be done consciously. Group study and learning communities are also critical. A study at the University of California, Berkeley, confirmed the role of studying together in improving academic performance of African American students who were struggling with their grades (Treisman, 1985).3 Dr. Pettigrew’s program at Texas A&M uses a flipped classroom model that relies heavily on group study, and test performance has shown a narrow bell-shaped curve in grades. “Our thinking is that this narrowness is a consequence of students learning from and teaching each other,” he said. Bringing students into research experiences in which they can explore their own research idea will pay dividends, as will mentoring across the career spectrum, he added. As shown in a “persistence framework” (Graham et al., 2013), a feedback loop leading to increased confidence and identification as a scientist begins with active learning (see Figure 2-2).

A fourth area for intervention centers on understanding local challenges. He spoke from his own experience studying and working at several institutions, and observed each had its own culture. He underscored the need for rigorous analysis of institutional data to understand specific needs and which interventions have been successful. Data analysis can help guide and give feedback for continuous improvement. At each institution, he added, there needs to be buy-in from the leadership to have representation of minority people at all levels and fully involved in the institutional fabric, and not just serve as tokens.

Fifth, Dr. Pettigrew said, is to facilitate entry into the STEM pipeline at multiple life stages, rather than prescribe a given pathway. He noted life experiences may require this, as illustrated by Carl Allamby, M.D., a grandfather who became a physician at age 48. His nontraditional path

___________________

3 Recent work also supports these findings. See, for example, Thelamour et al., 2019 and Carter, 2007.

SOURCE: Roderic Pettigrew, Workshop Presentation, September 2, 2020, from Graham et al., 2013.

began when he took a biology class at night, taught by a physician who mentored and encouraged him to pursue his dream (Rubin, 2020). Many other promising students cannot follow the traditional route but would make excellent STEM professionals.

Sixth, as Dr. Sullivan discussed above, financial support is critical. Black and Brown students come from families with, on average, the highest debt and lowest income across populations. Many cannot take on debt to attend graduate or medical school.

As a seventh intervention, he strongly agreed with Dr. Malcom about the need for a system approach that involves students, faculty, research opportunities, and leadership. “We need to move away from point interventions to think about interventions that take place across the whole spectrum to recruit and make sure these students persist to a professional end,” Dr. Pettigrew concluded.

UNDERSTANDING TRENDS AND NEW OPPORTUNITIES

In strongly supporting the points made by the previous presenters, Dr. Nivet called attention to the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, or TIMSS, conducted every 5 years.4 In the last three reports, the United States has lagged far behind other countries among all students in 4th-grade math and 8th-grade math and science. “What I would submit to you is that if we are falling behind as a country, underrepresented minorities are falling further behind,” he stated. Overall, math and science are underappreciated in the United States, he said, with a disproportionate impact on minority students, particularly Black students.

There is a lot of discussion about the educational pipeline, he observed, and he has heard negative comments that pipeline programs do not work. He disagreed. “If you look at the data, pipeline programs have worked for decades and continue to work,” he stated. “To say we are not seeing results is not just an underappreciation but also a lack of understanding about what pipeline programs are doing.” Numbers would be lower without them, he contended:

The way to think about a pipeline—people forget there are pumps in a pipeline. You don’t put oil or water in a pipe and expect it to flow through. You have to have the pumps—interventions that pump fuel through this pipeline. We have to be data driven. Pipeline programs continue to be an exceptional component of getting to better outcomes.

Another critical component is investment, or, as is currently the case, underinvestment in pipeline and other interventions. Pipeline programs and other supports have seen a reduction in investment by the government and by many philanthropies. He shared a saying from his mother that “politicians hurt those the most who can hurt them the least.” The U.S. Congress, he pointed out, has about 13 percent African American representation for the first time in history, which parallels the general population. “There is no better moment in time to agitate effectively for resources in a macro, larger approach for effective achievement. We have to put our heads around a new set of policy changes and arguments,” he stated.

The country continues to underinvest and undervalue the role of HBCUs and their production of students going on to STEM careers, Dr.

___________________

4 For more information, see https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/about.html.

Nivet commented. Data show their combined contribution in sending students on to medical schools and other professions. Advocacy for more resources for HBCUs would provide a huge opportunity to redouble their efforts and see outcomes.

On a personal note, he shared how his own son is looking at university programs that are supportive, rather than those that “weed out” students in STEM majors. He expressed dismay about the numbers of smart minority students who enter STEM programs without knowing how to navigate the system effectively and are adversely affected as a result. He called for active support for such students through nonprofit organizations, community groups, and informal conversations with young people.

DISCUSSION

Dr. Holden began the discussion by referring to Dr. Pettigrew’s definition of persistence. Mentoring in Medicine, the organization she leads,5 has done studies that show that lack of confidence is the top reason students do not succeed. Interwoven through all the presentations, she commented, was the importance of continually advising students and allowing them to see people who look like them doing what they want to do. She asked Dr. Pettigrew about steps to build persistence. Confidence is critical in almost every endeavor, he agreed, and it begets success. The concept of persistence rather than retention resonates with him, he added, because of its focus on students and student agency, rather than on the institution. The outcome is the same, but the nuance between persistence and retention means engaging with students and involving them more.

Dr. Sullivan stressed the importance of expectations set at HBCUs. In his class of 59 students at Morehouse in 1954, one-third were pre-med and went on to medical school. The culture of the school at the time was to instill a sense of responsibility, service, and excellence. Having that confidence and willingness to take risks makes a difference for success. It is an intangible but results in a real difference in outcomes, he said, and the other presenters agreed.

It is also important to work as a society to push for the federal government to invest in young people, Dr. Sullivan continued. By abdicating this responsibility, only those who come from wealthy families have opportunities. Data from the AAMC show that, in 2014, the average family income

___________________

5 More information available at http://medicalmentor.org.

of students entering medical school was $120,000, yet the average Black family income was $35,000 (Sullivan, 2016). With that disparity, financial barriers represent a major issue. The support is needed so that having a high family income is not a prerequisite to pursue a career as a health professional. Without it, a lot of talent is going to waste and is not being developed, he said.

Charles Bridges, M.D., Sc.D., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, commented on the disproportionate contributions of HBCUs to STEM graduate and medical schools. He asked about expanding their number, given this success. Dr. Malcom agreed with the need to invest in HBCUs, but suggested investing in or shoring up those with strong STEM programs, rather than creating new institutions. She said many schools are in precarious shape, exacerbated by COVID-19. Dr. Nivet agreed many lesser-known schools have “punched above their weight” and would benefit from additional resources, but he expressed the need for an additional African American medical school to provide support and set high expectations, particularly for Black males. He suggested creating such a school at an HBCU that already has a strong science and research orientation.

To increase the number of Black students who pursue rigorous STEM courses to prepare for college, Dr. Malcom called for celebrating excellence in STEM fields, beginning in high school, as is done for sports. Students in AP courses may feel alienated if they are the only or one of a very few Black students, and may also feel alienated from their Black peers outside the classroom, she said. A participant asked how to move to a systems approach rather than multiple, fragmented programs. Dr. Malcom noted pipeline programs have been successful, but the challenges come with how to scale them. She noted the large amount of money that goes to research at colleges and universities. “Who is benefiting from this? Who are the research assistants?” she asked. “If we look at the data, they are not African American students.” She commented that very little is asked of colleges and universities who receive grant funding, but they “must be asked to do their jobs, which includes educating Black and Brown students, and be held accountable.” She suggested the Roundtable look at how to put more systems approaches in place along the pathways that young people follow.

REFERENCES

Carter, D. J., 2007. Why the Black kids sit together at the stairs: The role of identity-affirming counter-spaces in a predominantly White high school. The Journal of Negro Education 542–554.

GMENAC (Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee). 1981. Summary Report of the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee to the Secretary, Department of Health and Human Services. Vol 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (DHHS publication no. (HRA) 81-651).

Graham, M., J. Frederick, A. Byar, A.-B. Hunter, and J. Handelsman. 2013. Increasing persistence of students in STEM. Science 341(6153):1455–1456.

Hendren, N., and B. Sprung-Keyser. 2019. Unified welfare analysis of government policies. NBER Working Paper. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26144.

RWJF (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation). 2020. Health Equity Principles for State and Local Leaders in Responding to, Reopening, and Recovering from COVID-19. Issue Brief. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/05/health-equity-principles-forstate-and-local-leaders-in-responding-to-reopening-and-recovering-from-covid-19.html.

Rubin, R. 2020. From auto mechanic to emergency room resident: Inspiring young Blacks to become physicians. JAMA 24(8): 227–229.

Seymour, E., and A.-B. Hunter (eds.). 2019. Talking about Leaving Revisited: Persistence, Relocation, and Loss in Undergraduate STEM Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Sparks, S. 2020. In 8th grade, separate algebra is unequal algebra for Black students. Education Week (blog, June 11). https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/inside-schoolresearch/2020/06/black_students_algebra_content_separate_and_unequal.html.

Sullivan, L. 2016. Grasping at the moon: Enhancing access to careers in the health professions. Health Affairs 35(8). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0382.

Thelamour, B., C. George Mwangi, and I. Ezeofor. 2019. “We need to stick together for survival”: Black college students’ racial identity, same-ethnic friendships, and campus connectedness. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 12(3):266.

Treisman, P. M. 1985. A Study of the Mathematics Performance of Black Students at the University of California, Berkeley. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley.

This page intentionally left blank.