Exploring the State of the Science of Stem Cell Transplantation and Posttransplant Disability: Proceedings of a Workshop (2022)

Chapter: 4 Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Survivorship

4

Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Survivorship

Margaret Bevans, the director at the Office of Research Nursing at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), introduced the third session of the workshop, which was designed to examine aspects of physical, cognitive, psychological, and psychosocial function after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in both adults and in children, as well as the interventions that can affect patient functioning and quality of life. This session features presentations by patients, caregivers, and clinicians; each of these brings a unique perspective reflecting the range of outcomes and experiences following a transplant.

PATIENT AND CAREGIVER EXPERIENCES

Suzanne McCarroll is a longtime survivor of both an autologous and an allogeneic transplant. McCarroll joked that while it has been a long road, managing insurance claims and medications was more difficult than the transplant itself. McCarroll left her job as a TV reporter because of a number of transplant-related factors, including being immune compromised, having “prednisone puffy cheeks,” and difficulty speaking owing to graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) symptoms in her mouth. She told workshop participants about a doctor in the hospital who had difficulty believing that she had ever been on television and thought perhaps the medication had made her confused. His perception of her was “accurate” at the time, but funny to hear, said McCarroll. While this was a job she dearly loved, McCarroll said she believes she has done well in terms of enjoying her life and making the best of things. She credited her family and

friends, and said it was critical to keep a sense of humor about the “crazy predicaments you get into and questions you’re asked and things you have to do.” Without a sense of humor, she said, “I don’t know how you would survive.”

Margaret Jurocko was the primary caregiver for her son, Jackson Taylor, who received a transplant as a senior in high school. Jurocko said that her journey as a caregiver started long before the transplant, as both of her children were born with a rare genetic condition called XMEN that put them at risk of contracting bacterial and viral infections and lymphoma. Jackson, who is now 22, was diagnosed with lymphoma during his first week of senior year, and received a bone marrow transplant 4 months later. Although Jurocko was fortunate to have a large support team of family and friends, being a caregiver following her son’s transplant was difficult both physically and emotionally. Jurocko said it is important for her to share her experience and advocate for the needs of caregivers because caregivers “rarely take the opportunity to talk about our needs, or our anxieties, because we’re always so focused on the physical needs and mental well-being of our patients.”

Medical teams could do a better job of preparing caregivers for common effects of transplant, said Jurocko. It is very difficult to absorb and remember the “wealth of information” about the transplantation process, particularly when the recipient is a loved one. For example, she said, Jackson experienced 45 days of side effects from an infection called BK virus. This virus increases the frequency and pain of urination, and can cause blood in the urine. As a caregiver, Jurocko said she “felt helpless.” She tried assisting him in walking to the bathroom, helping nurses collect samples, and managing his pain. The nature of the condition created a “bit of an uncomfortable situation between mother and son,” but they persevered and got through the challenge.

On top of dealing with health challenges, Jurocko had day-to-day responsibilities such as prescription medication scheduling, doctor appointments, and keeping the house clean to avoid infection, along with the usual responsibilities of managing a home and family. In addition, Jackson wanted to graduate with his senior class so Jurocko had to coordinate tutoring, communicate with teachers, and facilitate school participation. These responsibilities were “very significant for the well-being of Jackson,” she said. While Jackson did graduate, he was not able to attend college with his peers until a year later, which was a “real emotional loss” for him. Jackson was in isolation at home for many months after his transplant; Jurocko said that today the concepts of isolation and distancing and mask wearing are common, but in 2017, “we didn’t have the rest of the world participating alongside of us.”

The year after the transplant was like a roller coaster, said Jurocko. She said it is important for caregivers to stay “as positive as possible” for their patient while simultaneously dealing with their own issues and needs. The potential financial effect of caregiving is very significant, said Jurocko; to

reduce the risk of exposing Jackson to infections, she put her career on hold for 2 years because her job involved going into clients’ homes. She encouraged families to make financial plans prior to transplant when possible. The emotional impact was heavy as well; Jurocko said that after 2 years of caregiving, she was less optimistic, less self-assured, and less confident when she returned to the workplace. She attended pre- and posttransplant therapy with a psychiatrist who gave her practical tools to understand and cope with the magnitude of managing her son’s transplant. In addition, she said being friends with another caregiver she met while Jackson was undergoing his transplant “really brightens our days and gives both of our families hope.” Jurocko now serves as a Peer Connect volunteer with Be the Match (https://bethematch.org), which allows her to offer support to other caregivers who are experiencing similar challenges. Jurocko said that the journey that the family has been on and continues to be on has made them stronger and much closer. Jackson is thriving, she said, and that getting to this point has required intense focus and real sacrifice, but “the outcome has definitely been worth it.”

ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTION

Physical and Functional Outcomes

Karen Syrjala, professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, said that there are myriad long-term effects of HSCT including physical, psychosocial, and functional effects. Syrjala presented data from a scoping review that examined long-term functional outcomes for transplant patients (Bevans et al., 2017). Long-term physical function was impaired in around 35 percent of transplant survivors, and the rate of physical inactivity was even higher, at around 85 percent. Between 40 and 50 percent of survivors experienced sleep disruptions, emotional distress, fatigue, and/or cognitive dysfunction, and around 40 percent had not returned to work. However, despite these effects, another study found that 85 percent of survivors had experienced positive changes related to their transplant, including resilience and personal growth (Bishop et al., 2011). A large majority (76 percent) of caregivers also reported positive changes as a result of going through the transplant process.

For most HSCT survivors, returning to a pretransplant state of physical, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning takes years, said Syrjala. Recovery to pretransplant physical function takes around a year, but at 10 years, transplant patients still have lower levels of functioning than nontransplant controls (Syrjala et al., 2005). Cognitive function recovery can take 2 to 5 years (Syrjala et al., 2011); Syrjala et al. noted that it can be difficult to measure real-world cognitive function and that survivors often report difficulty focusing and multitasking, tasks which are not well-measured in standard neurological

testing. Emotional recovery takes at least 2 years, and at 10 years survivors still have poorer mental health and greater use of psychiatric medications than nontransplant controls (Syrjala et al., 2004, 2005). Full return to work takes up to 3 years (Kirchhoff, 2010; Bhatt, 2021). For many functional outcomes, said Syrjala, a person’s social support and social network can have a large effect (Amonoo et al., 2021; Nørskov et al., 2021); for example, a person may be more likely to be able to return to work if he or she has someone to help with daily living roles such as transportation and household care. Syrjala also emphasized that these numbers are averages, but recovery is a very individual process. People begin at different points and have different goals and needs, so their pace and extent of recovery can vary based on their goals and demands for functioning.

Assessing physical and functional outcomes can be challenging, said Syrjala. There are four main sources of information: patient-reported outcomes, physical performance functional tests, lab-based exams, and medical records. When looking at medical records, she said, it is important to consider who is inputting the information and what their focus is. For example, an oncologist who is focused on treatment and recurrence is unlikely to prioritize evaluation of a patient’s physical ability to return to work. While these records can provide valuable information, she said, it is necessary to look beyond medical records when assessing patient function. Online assessments are an invaluable tool for capturing patient-reported outcomes; Internet access is widely available and used, and online tools can be completed by greater than 90 percent of transplant survivors (Wood et al., 2013; Shaw et al., 2017). A number of validated assessment tools are available for measuring different types of function, said Syrjala, including:

- PROMIS measures global physical function, mental function, health-related quality of life, depression, and anxiety (Fries and Cella, 2005; Shaw et al., 2018).1

- SF-12 (Ware et al., 1996) measures global physical function and mental function.

- PRO CTCAE (Basch et al., 2014) measures health-related quality of life.

- PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001) measures depression.

- GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) measures anxiety.

- PCL-5 (Weathers et al., 2013), PCL-C (Weathers et al., 1991), and PC-PTSD-5 (Prins et al., 2015) measure post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

___________________

1 PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, and the PROMIS logo are marks owned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Measures like these are important, said Syrjala, but additional issues need to be captured and addressed in the cancer and transplant population. Survivors of HSCT often deal with issues such as an awareness of uncertainty, fearof recurrence, demands of living with physical limitations, financial burden, and concerns about family. Tools have been developed to evaluate these measures of distress, including the Distress Thermometer (Riba et al., 2019), the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983), and CTXD (Cancer and Treatment Distress) (Syrjala et al., 2016, 2017). CTXD was developed in the field of HSCT, and it has subscales that assess distress in six areas: uncertainty, burden of health problems, family strain, changes in appearance and identity, managing medical system, and finances. This tool, said Syrjala, can be used to identify people who are experiencing depression, anxiety, and trauma, as well as people who may not meet the clinical criteria for these disorders but are experiencing distress to an extent that negatively affects their life.

Physical performance tests that are widely used include the 6-minute walk, a one rep max strength test, hand dynamometer, or treadmill stress test of aerobic capacity. Assessments of physical activity level can be performed using patient reports, or with real-time measures such as accelerometers, pedometers, or other wearables and sensors. An important measure of physical function is frailty, which is assessed using five criteria: low muscle mass, low energy expenditure, slow walking speed, weakness, and exhaustion. Frailty is ideally assessed by physical performance testing, said Syrjala, but it can also rely on patient self-reports. Studies indicate that between 7 and 8 percent of young people are considered frail even years after HSCT (Arora et al., 2016; Eissa et al., 2017), and research has demonstrated that frail HSCT and other cancer survivors experience more chronic conditions and increased mortality risk (Fried et al., 2001; Ness et al., 2013, 2020; Arora et al., 2016, 2021).

Cognitive screening is most commonly performed using the MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) (Nasreddine et al., 2005). Syrjala said that the MoCA is not always sensitive enough to capture the cognitive dysfunction of transplant patients, but it is useful as a screening tool. It is recommended that full neuropsychological testing be conducted at least a year after transplant, because the majority of people will still be recovering and not stable prior to 1 year (Syrjala et al., 2011), said Syrjala. Sleep dysfunction can be assessed through patient self-report, using wearables, or in a sleep lab.

Lab-based tests to assess HSCT-related outcomes can include blood tests, portable testing devices such as blood pressure monitors, and scans to test for bone density and body composition. Syrjala said that aggregation of these types of lab-based tests is best for indicating risk for mortality, physical disability, or cardiovascular events. For example, metabolic syndrome—which is diagnosed using a combination of measures of blood pressure; lab tests for glucose, triglycerides, and cholesterol; and anthropometry for central adiposity

or body composition scans—is a condition that is elevated in transplant survivors and can predict cardiovascular events and survival (Greenfield, 2021). Another useful combined measure is sarcopenic obesity, which is indicated by low muscle mass with high fat mass. After HSCT, many survivors do not meet the criteria for obesity using body mass index but are obese based on high fat mass measured with DXA (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) or CT (computerized tomography) scans; sarcopenic obesity is present in 42 percent or more of HSCT survivors and predicts frailty and survival (DeFilipp et al., 2018; Armenian et al., 2019).

There are three commonly used measures for work performance: the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI) (Reilly et al., 1993), the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) (Lerner et al., 2001), and the WHO Health and Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) (Kessler et al., 2003). However, Syrjala said that no studies have used these three measures to assess transplant patients and that she looks forward to seeing them used in the future to get a pulse on the extent to which issues such as absenteeism, presenteeism, and other elements of work dysfunction are affecting HSCT survivors’ lives.

When it comes to assessing survivors for disability and return to work, said Syrjala, it is important to keep in mind that many of these measures are highly interrelated. “The worse someone feels physically, the worse they’re likely to feel mentally,” she said. Poor functional outcomes, whether measured by patient report, tests, scans, or exams, are closely tied to comorbidities, disability, and mortality. Further, mental, physical, and functional outcomes clearly affect work performance and disability, but they are not yet routinely measured to permit targeting interventions to survivors’ needs. The research shows that flexibility and accommodation in the work environment can improve work success by removing barriers to function, said Syrjala.

Survivorship: Physical and Mental Interventions

Areej El-Jawahri, director of the Blood and Marrow Transplant Survivorship Program at the Massachusetts General Hospital, said that HSCT survivorship focuses on addressing all of the domains that have been affected by a transplant, including physical late effects, psychosocial late effects, chronic conditions, cardiac comorbidities, pulmonary comorbidities, cognitive effects, potential for cancer recurrence, and health promotion. Survivorship care requires four types of action: prevention, surveillance, intervention, and coordination. Prevention includes avoiding recurrence of underlying cancers and development of new cancers, as well as preventing late effects. Surveillance is necessary in order to become aware of new problems, such as recurrent cancer, psychosocial late effects, or physical late effects. Interventions can work to

prevent or mitigate new issues, and to improve the overall lived experience of our patients and their families, she said. One piece that is often missing, said El-Jawahri, is coordination of care; survivors have complex and unique needs across multiple specialties.

Given these complex realities, the ideal model for HSCT survivorship care is a long-term, multidisciplinary or transdisciplinary survivorship clinic, where patients can meet with a wide variety of specialists to address their particular needs including:

- dermatology,

- ophthalmology,

- oral health,

- cardiology,

- pulmonary,

- endocrine,

- sexual health and fertility,

- physical therapy and rehabilitation,

- occupational therapy,

- psychology,

- infectious disease,

- neurology, and

- gastroenterology.

About 50 percent of transplant programs have long-term follow-up programs; however, many HSCT transplant centers do not have programs or do not have all of the necessary specialties or services available. Part of the challenge, said El-Jawahri, is “pure logistics.” For small and medium clinics, it is not logistically or financially feasible to arrange a clinic with all the necessary specialists in one room. Another challenge, said El-Jawahri, is a lack of expertise; HSCT survivors require specialists who have a specific understanding of the complications related to transplant, particularly chronic GVHD. The final barrier to high-quality survivorship care is a “sense of ownership over addressing the survivorship care needs of transplant recipients.” El-Jawahri said that transplant clinicians can struggle to involve primary care providers in the care of patients. She said that transplant clinicians have a desire to be the primary caretaker for their patients, but this can result in isolation from primary care providers who “also have a lot of expertise to offer.”

To help survivors function and thrive after HSCT, said El-Jawahri, many interventions have been tested. El-Jawahri first shared the details of interventions designed to promote physical functioning. Exercise interventions typically begin before or during transplantation, last between 1 and 6 months, and often include both aerobic exercise and muscle strengthening.

The interventions vary in intensity, and some are supervised while others are partially supervised. Despite this heterogeneity in the design of interventions, said El-Jawahri, numerous trials have shown the benefit of exercise interventions on outcomes including cardiorespiratory fitness, quality of life, and fatigue. Studies show moderate positive effects on cardiorespiratory fitness and lower extremity strength, small to moderate positive effects on quality of life and fatigue, and inconsistent evidence on the benefit of exercise for emotional well-being (Persoon et al., 2013; Mohananey et al., 2021; Prins et al., 2021).

The evidence indicates that the most effect interventions are the ones that are more intense and involve more supervision, she said. El-Jawahri emphasized the need for physical exercise interventions in patients with chronic GVHD, as these patients can suffer from reduced functional capacity, muscular and functional limitations, inflammatory disease, and sarcopenic obesity (Fiuza-Luces et al., 2016). She also noted that as most interventions end within 6 months, there is a need for more research on the long-term outcomes for HSCT survivors.

Interventions designed to promote mental functioning fall into two categories: those that address the mind–body connection and stress management, and those that use cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The first category of interventions uses techniques such as relaxation, guided imagery, breathing exercises, and progressive muscle relaxation, said El-Jawahri, and are generally conducted during HSCT with a short follow-up time. These interventions have shown small effects on anxiety, depression, and fatigue, but suffer from poor adherence when self-directed (Bevans et al., 2017). CBT interventions have shown greater benefits, she said, including lower distress and improved emotional functioning (Baliousis et al., 2016). There is evidence that benefits endure up to a year after a transplant, and more intensive interventions yielded larger and more significant benefits. The CBT interventions are limited, however, as they included largely White patient populations and did not target high-risk patients.

Another interesting study, said El-Jawahri, was a CBT intervention focused on studying PTSD in HSCT survivors (DuHamel et al., 2010). Patients who were 1–3 years posttransplant and who had significant PTSD-related distress were randomized to receive either a telephone-based CBT intervention or usual care. The CBT intervention improved PTSD symptoms and led to a reasonable reduction in global distress and depression symptoms, said El-Jawahri. Interventions to improve mental functioning are critical, said El-Jawahri. Transplant patients are at risk of mental issues such as depression and anxiety, but furthermore, mental health status is strongly associated with transplant outcomes including survival, risk of GVHD, health care use, and length of hospitalization.

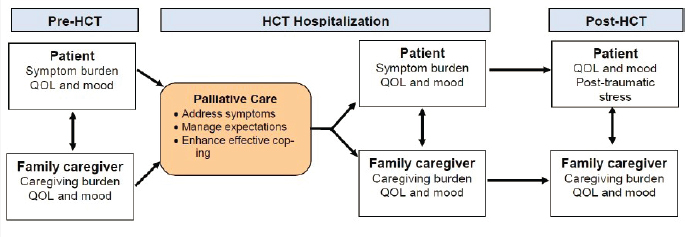

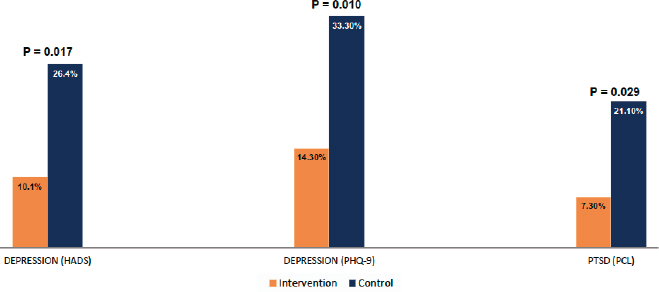

Palliative care is an approach that has been studied in the acute transplant hospital stay setting, said El-Jawahri, and has promise in improving both short- and long-term outcomes. Palliative care is often thought of as end-of-life care, but in this setting, it is simply care by a team of experts who can help patients live as well as possible. El-Jawahri presented a conceptual model of how palliative care can be integrated into the HSCT process (Figure 4-1). This model was assessed in a study that enrolled 160 patients with hematologic malignancies within 72 hours of admission for HSCT (El-Jawahri et al., 2016). Patients were randomized to either receive standard transplant care or inpatient integrated palliative and transplant care in the form of at least two visits weekly during HSCT hospitalization. Data were collected in the second week after transplant, and again at 3 and 6 months. The initial data revealed medium to large effect sizes of the intervention, with improvement in quality of life, symptom burden, depression, and anxiety. At 6 months, these patients showed sustained improvement, with a reduction in clinically significant depression and PTSD symptoms (El-Jawahri et al., 2017) (Figure 4-2). El-Jawahri said that this demonstrates that interventions conducted during the acute hospital stay can lead to benefits up to 6 months posttransplant.

Looking forward, El-Jawahri said that several research gaps need to be addressed. Physical medicine and rehabilitation interventions need to be developed and tested for HSCT survivors. Physical exercise interventions need to be tailored and refined in order to improve recovery for survivors, and there is a particular need to focus on patients with chronic GVHD. Researchers and practitioners need to consider how to scale and enhance accessibility of these interventions in order to reach more transplant survivors.

NOTE: HCT = hematopoietic cell transplantation; QOL = quality of life.

SOURCES: As presented by Areej El-Jawahri, November 15, 2021; El-Jawahri et al., 2016.

NOTE: HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PHQ-9 = depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire; PCL = PTSD Checklist; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

SOURCES: As presented by Areej El-Jawahri, November 15, 2021; El-Jawahri et al., 2017.

Pediatric Outcomes

Staci D. Arnold, associate professor of pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine and director of the Comprehensive Bone Marrow Failure Clinic at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said that HSCT has a curative intent, but disability is not always prevented or halted by a transplant. There are issues and comorbidities related to both the underlying disease as well as the transplant itself, and these effects can be felt in a wide variety of domains, from employment to mental health to physical function. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are a common way to collect data on transplant survivors, both for research purposes and to intervene when appropriate. However, said Arnold, PROs are challenging in the pediatric population for several reasons (Bele et al., 2020). First, children are often unable to articulate all of their needs, and this may delay early intervention services. Second, age-related variations in vocabulary and comprehension of health concepts can make it difficult to design appropriate PRO tools. Finally, frequent hospitalizations and medical visits, along with school absenteeism, can adversely affect psychosocial development and the ability of children to communicate about their needs and experiences.

These challenges, said Arnold, result in a system of “dual responses” in which patients and caregivers provide some first- or second-hand information, but critical information is still missing. For example, caregivers often provide ample information about how their child is doing, but are not as transparent or forthcoming about their own well-being. Despite these challenges, said

Arnold, there are a number of existing measures to look at PROs and quality of life in children, including PROMIS, PedsQL (Varni et al., 1999), the Beck Youth Inventory (Beck et al., 2001), and EQ-5D-5L (Derrett et al., 2021).

While these types of tools for collecting PROs are essential, Arnold said that it is critical to also engage patients and families in order to determine what aspects of recovery and function are important to them. Burns et al. (2018) engaged patients and caregivers in a process to develop a patient-centered outcomes research agenda. This process, said Arnold, gave patients and caregivers a voice in their care, allowed patients to understand the transplant journey, built a sense of community, and gave patients an opportunity to delineate their experiences for other patients in the future. One participating patient said, “We thought we’d go through the transplant process and get back to our life; it’s been everything but that.” This statement, said Arnold, addresses the importance of the need to better understand the quality of life, issues with disability, and other outcomes associated with transplantation. The patient-centered outcomes research agenda focused on six topics:

- Patient, caregiver, and family education and support

- Sexual health and relationships

- Physical health and fatigue

- Emotional, cognitive, and social health

- Models of survivorship care delivery

- Financial burden

Financial burden is one of the areas that can have the largest effect, said Arnold, for both patients and caregivers. A child’s education serves as the foundation of his or her future financial potential; any effect that a transplant has on memory, social function, or social isolation can affect the child’s education and future. Patients may have difficulty obtaining employment in the future because of issues with their educational history, or because they need to find an employer with health benefits that are sufficient for their needs. Pediatric patients may experience a loss of insurance coverage during transition periods, and some patients may be ineligible for certain benefits based on their diagnosis or lack thereof. For example, a patient may be technically “cured” of sickle cell disease after HSCT, but may carry long-term sequelae of that disease. Finally, pediatric patients may deal with financial burdens related to reproduction, such as fertility preservation and reproductive assistance. This may be particularly costly for children who may not use the services for many years.

Unfortunately, few PRO measures have been validated for use in this patient population to capture financial information, said Arnold. Arnold and her colleagues set out to design a validated measure that captures traditional financial measures such as income, as well as HSCT-specific measures such

as costs of medication and trade-offs between different needs (Arnold et al., 2020). The researchers found that participants could convey the financial effect of HSCT within the scope of the survey, and also that they were unaware of many available financial resources.

Arnold told workshop participants about studies that looked at social determinants of health in the transplant population. One study looked at two cohorts of pediatric patients receiving an allogeneic transplant over a 10-year period of time (Bona et al., 2021). Among those with malignant disease, neighborhood poverty conferred an increased risk of transplant-related mortality. In addition, Medicaid insurance was associated with inferior overall survival and increased transplant-related mortality when compared with private insurance. Another study of both adult and pediatric sickle cell patients found similar results: patients with Medicaid insurance had lower event-free survival rates and higher graft failure rates compared to patients with private insurance (Mupfudze et al., 2021). These results, said Arnold, suggest that economics play a substantial role in the patient’s experience and their transplant outcomes. Further, disparities in economics and insurance can lead to health disparities after HSCT.

To find ways to mitigate these disparities, Arnold said it is essential that we better understand the intersection between finances and HSCT outcomes. There is a need for better tools to capture this information. These tools and the evidence they produce will enable better resource allocation and policy making, said Arnold.

DISCUSSION

Bevans guided a discussion following the presentations, asking panelists questions from the workshop participants.

Q1: Following a hematopoietic stem cell transplant, if a patient committed to the interventions that are most critical for recovery, what would be the time commitment each week or month? What would be the time commitment immediately after the transplant, and what would it be a year posttransplant?

Certain evidence about interventions is clear, said El-Jawahri: higher intensity interventions lead to better outcomes, and supervision matters. For example, giving patients the opportunity to work directly with a physical therapist is better than giving them a video or a self-administered exercise program. Unfortunately, because of insurance coverage and accessibility, most patients are only able to receive a couple sessions of physical therapy a week for a couple of months, said El-Jawahri. For patients who are frail and deconditioned, “that is just not sufficient.” The use of telehealth may improve access

to physical therapy, as well as permit patients to receive physical therapy in the comfort of their home. A year post-transplant, the amount of time needed for interventions depends greatly on the individual patient, their needs, their complications, and their goals. Having a comprehensive program that is tailored to the needs of patients is critical, and as before, intensity and supervision matter. Arnold added that the time commitment depends in part on the specific type of treatment, but that the first year posttransplant is the most time intensive. As the patient recovers, the time commitment lessens; however, it can vary considerably depending on the complications and complexity of the patient.

Q2: What is the role of services such as physical rehabilitation during recovery from HSCT?

McCarroll said that after her transplant, she was not offered home care visits, rehabilitation, or physical therapy, but instead took informal walks and exercised with friends. Because of the side effects of the transplant, she fell and broke several bones. After these injuries, she was offered in-home occupational and physical therapy and it made a “world of difference.” McCarroll said she wished that all transplant patients could receive these services following a transplant. Jurocko said that her son, Jackson, participated in physical therapy for the first 100 days posttransplant. He improved greatly and enjoyed the physical activity and the independence that physical therapy gave him.

Q3: What is useful for patients to help them navigate the “financial jungle of reimbursement”?

McCarroll previously worked as a researcher and reporter for a news station; she said that she was “pretty good at researching and navigating until [she] hit the health care system.” Despite having good health insurance, she spent hours on the phone trying to “get through to a real person.” The system is a “web of confusion” and she said that she very seldom hung up the phone having her issues resolved. McCarroll said that given her experience, she didn’t feel very effective and did not have tips to share, unfortunately. El-Jawahri agreed with McCarroll that it is a difficult process to navigate and to determine who to talk to and what resources are available. She noted that there is a growing body of literature on patient navigation and financial distress, relating to both transplantation and to cancer and complex care in general. There is growing evidence, she said, that patient navigators who are empowered with the right information can play an important role in helping patients and families navigate the complexity of the health care system. Arnold added that one critical way to help patients is to begin the process of navigation and assessing financial hardship as early as possible. She noted that

providing advice, navigation, and access to resources before the transplant can dramatically improve the patient experience.

Q4: How do patient-reported outcomes inform the clinical care that HSCT patients are receiving?

Over time, we have come to appreciate the value of the patient voice, said Syrjala. Without understanding the patient’s problems and priorities, we cannot provide the best care and our interventions have a much lower chance of being successful. For example, she said, if a patient has financial challenges and has to choose between paying for medication and paying for food for their family, “whatever we prescribe is not going to be as effective” for that patient. It is critical that providers understand the context of the patient they are treating, not simply the medical biology.

Q5: Are there topics where patients and caregivers struggle to get an accurate picture of what HSCT entails? What hesitations might patients have in deciding whether to get a transplant?

Prior to her son’s transplant, said Jurocko, there was little discussion or information about how the transplant could affect identity and appearance. Her son’s hair loss has been extremely difficult for him, and even after 5 years, it has not grown back to where it was. The issues with his appearance have been a “significant mental dilemma,” and he will likely get a hair transplant soon. In contrast, said McCarroll, her doctor told her “every single worst case scenario” before her transplant. McCarroll said that she considered not going through with the transplant, in part because she was worried about dying and leaving behind her three children. However, a nurse that she had gotten to know well told her “I know you’ll be able to get through it,” and something about the nurse’s belief gave her the confidence to try the transplant. While she appreciated her doctor’s candor about the worst-case scenarios, she said she wished he would have also shared some stories of success.