Equitable and Resilient Infrastructure Investments (2022)

Chapter: APPLIED RESEARCH PRIORITIES

and environmental disparities that may limit community resilience. Full videos of the individual panelists’ contributions are available on the web page for the event.1

APPLIED RESEARCH PRIORITIES

Based on input from the workshop and committee members’ knowledge and experiences with natural hazard mitigation and resilience, the committee chose three applied research topics as priorities in motivating local action to address climate impacts and build resilience: (1) partnerships for equitable infrastructure development, (2) systemic change toward resilient and equitable infrastructure, and (3) innovations in finance and financial analysis. The following sections discuss each of these applied research priorities in detail. At the end of each section, the committee includes specific applied research topics and research questions that it considered important for advancing these priorities.

1. PARTNERSHIPS FOR EQUITABLE INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT

Targeted equitable public infrastructure investments can generate enormous community benefits in terms of reducing disparities in the quality of and access to services before and after hazard events. Improved equity can increase community resilience and further mitigate the uneven distribution of damage and losses stemming from extreme events. However, ensuring that investments for social, economic, and cultural community functions benefit all community members requires that equity be a focal planning goal and that all community stakeholders be included when identifying needs and prioritizing these investments. The committee identified two areas of research that would improve equitable community involvement: (1) effective partnerships for knowledge transfer and promoting action research and (2) building trust to enable productive and equitable community participation.

Partnerships for Knowledge Transfer and Promoting Action Research

Applied research has historically taken two approaches to community participation and inclusion: research on communities and research for communities. However, capitalizing on the fact that community members hold detailed and often insightful knowledge of local values, needs, constraints, and opportunities that would inform applied researchers requires a more inclusive research strategy—one that enables community stakeholders to drive and direct scientific inquiry. Action research, which seeks both to understand and to alter the problems generated by current social systems, is an approach for generating research about a social system while simultaneously attempting to change that system (Troppe, 1994). Although not a new concept, community-based participatory action research centered on equitable infrastructure would create a unique opportunity to include the community in the knowledge production process (see Box 4). Action research should be collaborative with and inclusive of the

___________________

1 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-17-2022/hazard-mitigation-and-resilience-applied-researchtopics-workshop-1-equitable-and-resilient-infrastructure-investments.

community being studied, and it should strive to achieve social justice through participatory action and social change (Miles, 2018).

Ideally, action research aspires to engage the public at all levels. In practice, however, the process of engagement requires time and interest that community members may not want to devote to that process because they may feel that their input will not be valued or that they do not have adequate time or resources for the requested commitments. Identifying the factors that inhibit community participation can enhance understanding of key barriers to broadening public participation in discourse and decision-making.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in the workshop, as well as on discussions with the Resilient America Roundtable and among the committee members, the committee identified the following applied research questions regarding partnerships for knowledge transfer and promoting action research for equitable infrastructure services and access:

- How can applied research on resilient and equitable infrastructure services and access be advanced using participatory action research concepts and principles where the process begins and ends with local communities?

- What are compensation models that value local expertise and how can they be modified to enable greater community participation by those affected by inequitable infrastructure services and access so as not to create additional undue burden on marginalized community members?

- How can community-to-community knowledge transfer of resilience and equity assessment and planning processes for infrastructure services be facilitated?

- What institutional processes would better enable community members to participate in action research?

- What mechanisms would ensure that community input and public participation in action research is actively reflected in equitable and resilient infrastructure planning and development rather than just “heard” and how can we verify/validate the success of such processes and mechanisms?”

In addition, the committee noted the following 3 factors that would enable partnerships for knowledge transfer and promoting action research:

- Provide sustained funding directed to the community to support long-term relationships, ongoing community engagement, and capacity building.

- Require research to be undertaken with or by the community rather than for or on the community.

- Develop institutional processes that enable community members to participate.

Building Trust to Enable Productive and Equitable Community Participation

Individuals and communities develop trust over time through observation of consistent behaviors such as clear and unbiased communications, inclusion of and interactions with stakeholders, and ownership of outcomes. In times of stress, the absence of trust can lead to inefficiencies or lack of timely actions that may lead to unintended community impacts. Once trust is lost, it is extremely difficult and time-consuming to restore. Ongoing legacies of inequitable treatment degrade trust and opportunities to identify infrastructure investments that improve resilience and equity of infrastructure services. Unwelcome change can also affect trust levels. Change in communities can be related to improvements before, during, or after disruptive events, where the pace of change and acceptance of its necessity often vary by the degree that individuals or groups are affected.

Research has linked trust within communities to stronger volunteerism, healthier residents, and economic prosperity (Putnam et al., 2004), and it is an essential ingredient in any successful community-based participatory research partnership (Christopher et al., 2008). The workshop informing this report identified four areas where trust is essential to engaging communities effectively: trust in government programs and decisions, trust in institutions, trust in information and data, and trust built with community members.

Transparency is important for building trust. Community plans and efforts should be clear and well understood by all stakeholders, devoid of hidden or alternative agendas, and honest about the role and influence citizens will have in either the decision-making or implementation of solutions (see Box 5). Part of being transparent is sharing information widely between all stakeholders as a means of ensuring that everyone is working from a common understanding of the issue and each other’s perspectives.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions pertaining to trust as it related to equitable and resilient infrastructure development:

- What role does trust play in the development and provision of resilient and equitable infrastructure?

- What role does trust play in the recovery of functions and services of resilient and equitable infrastructure?

- What strategies and tactics can be deployed at the institutional level to regain and grow trust where it has been frayed, especially during times of change resulting from stressors and acute disruptive events?

In addition, the committee noted the following 3 factors that would enable trust:

- Understand the current status of infrastructure services and performance as a baseline or background information for state of trust between stakeholders.

- Cross-reference and coordinate plans and goals for related topics between multiple stakeholders, such as community plans and infrastructure owners and operators.

- Consider the roles and interests of infrastructure ownership, such as public versus private institutions and organizations, and renter versus owner.

BOX 5

Trust and Community Resilience Planning for Affordable Housing

In California, Enterprise Community Partners launched a community-powered resilience initiative offering community organizations and local governments resources and actions to implement for equitable resilience planning and recovery. Community-led resilience is about investing in communities based on their issues, listening to their solutions, and redirecting resources. Nationally, Enterprise includes materials, training, and manuals in their resilience academies and assessment tools to help affordable housing owners engage with a property’s residents. That engagement is crucial to build trust and a relationship, avoid unintended consequences, and build a community’s motivation to steward their own resilience and recovery efforts. Enterprise Community Partners focuses on meaningful trust building and engagement with residents when completing retrofit and rehabilitation of existing properties. Without resident engagement, building owners will not necessarily make the best decisions about which buildings to prioritize and how to incorporate the unique needs of the residents as they improve properties for resilience.

2. SYSTEMIC CHANGE TOWARD RESILIENT AND EQUITABLE INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT

Inequity can be hard-wired into mature and stable institutions, such as federal and state agencies, city officials, public planners, and the entities that develop infrastructure. Too often, however, institutions do not recognize they have a problem, and even when they do, they may have difficulty bridging the gap between awareness of inequity and substantive change, which in turn can contribute to failed outcomes in building resilient and equitable infrastructure. While resistance to change can be a strength during times of stability or minor turbulence, it can lead to a crisis of confidence in the institution as increasingly unbearable outcomes continue to afflict populations these systems should serve.

Assumptions, norms, processes, and procedures that evolve over long, stable periods may no longer serve when political, social, or ecological baseline conditions shift. Under pressure to change, mature institutions often resist wholesale change, though they may establish limited-scope programs or implement pilot projects to evaluate and demonstrate new ways of thinking or new approaches to solving problems. These pilot projects, while an important first step, are insufficient to stimulate the systemic change required to address the complex challenges of social injustice and inequitable provision of infrastructure introduced by climate change.

During the process of reaching consensus, the committee identified six areas of research that would inform institutional efforts to put equity at the center of their infrastructure investments: systemic change, resilience hubs, community resilience planning, integrated multi-benefit solutions, interdependence of built and natural environments, and minimum code requirements.

Systemic Change

Inequity in infrastructure investments can become visible when access to infrastructure services and post-disaster recovery timelines disproportionately impact some communities more than others. Good intentions to change, even when desired, can be difficult to accommodate in mature and stable organizations, utilities, corporations, and governments. More established organizations can resist change even as baseline conditions shift. Complex natural and human systems do change, however, when profound shocks (e.g., acute disruptive or damaging events such as hurricanes, earthquakes, or floods) and stressors (e.g., chronic conditions such as drought or sea level rise) can force these systems to adapt and or transform (Westley et al., 2013; Gunderson and Hollings, 2002; Hollings, 1986;). Times of stress and shock create opportunities for organizations to undergo systemic change, and pilot projects that model new patterns and relationships can often find broader applicability following a disruption (Westley et al., 2013).

It is during these times of disruption that once-stable systems are most open to innovation and opportunities for change (Dorado, 2005; Snowden and Boone, 2007; Westley et al., 2013). Change agents outside of the system and institutional entrepreneurs within the system can forge new collaborations and new alliances that may redeploy resources to novel endeavors (Snowden and Boone, 2007). These new combinations and alliances can seek to guide their institutions toward new stable states with adapted norms, processes, procedures, and outcomes (Plowman et al., 2007; Westley et al., 2013).

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions regarding systemic change and equitable infrastructure investments:

- What models of system change are most useful for institutions to achieve equitable infrastructure investments? For example, what can applied researchers in equitable and resilient infrastructure investment learn and apply from the CommuniVax Coalition’s process and plan? (see Box 4)

- How can equity-focused change agents and institutional entrepreneurs—individuals with an interest in particular institutional arrangements and who leverage resources to create new institutions or to transform existing ones (Maguire et al., 2004, p. 657)—be identified and supported?

- How can successful pilot projects be rapidly scaled to reliably deliver equitable outcomes?

- How can infrastructure providers and investors stimulate their institutions into meaningful and lasting change to address inequitable outcomes? How can these institutions make equity an explicit goal and hold themselves accountable for achieving or advancing equity.

In addition, the committee noted factors that would enable systemic change in infrastructure investments including:

- Provide access to relevant data, such as results from previous pilot projects, with the requirement for pilots to be documented and reviewed prior to systematic investments.

- Develop ways to apply adoption of equity-focused innovations.

- Conduct pilot validation prior to system implementation.

Resilience Hubs

Community resilience hubs provide holistic support to communities during disaster and recovery periods, as well as throughout the year. Resilience hubs should be community-serving facilities that are designed in collaboration with communities and augmented to support residents and coordinate communication, distribute resources, and increase the community’s adaptive capacity while enhancing quality of life (Baja, 2019). They provide the opportunity to work at the intersection of community resilience, emergency management, climate mitigation, and social equity while also helping communities to become more self-determining, socially connected, and successful before, during, and after disruptions. Strong relationships and communication built throughout everyday operations can both strengthen community capacity to face disasters and ensure that resilience hubs are trusted resources in times of emergency.

Resilience hubs have the potential to support historically underinvested and vulnerable communities (such as those facing increasing climate risks) during and after disaster events as well as throughout the year, but siloed funding—such as funding dedicated for emergency operations only—and limited data access and transparency limit the effective design, deployment, and operation of community resilience hubs. To be effective, resilience hub designs must reflect local needs, priorities, and the unique characteristics of their surrounding communities and account for historic inequities and vulnerabilities. A top-down, one-size-fits-all approach does not work, but funding and research often fails to support the design of centers reflecting community-based priorities and needs and fails to provide the kinds of holistic services required to serve the community. Needed services include resilient services and programs to increase human adaptive capacity and enhance the development of strong relationships and trust with the community; resilient communications both during a disaster event and with the community throughout the year; resilient landscape and buildings inclusive of green design and reflective of the natural environment; resilient power systems such as solar energy plus energy storage capacity; and resilient operations and maintenance supported by consistent and reliable funding. These holistic approaches can contribute to strengthening relationships and trust required for effective year-round, disaster, and recovery modes.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions on the topic of resilience hubs:

- What are the policy and regulatory barriers in different states and jurisdictions that limit resilience hub deployment, and how may these be overcome? Examples may include the following:

- Utility-level requirements, such as prohibitions to linking together multiple buildings with different electric meters

- Grid interconnection standards limiting optimal system design or posing challenges to islanding systems

- Poorly designed incentives for solar + storage, such as those based on narrowly-defined benefit-cost calculations and omitting the value of resilience

-

What are effective financing strategies to support resilience hub facilities and operations during emergency events, recovery, and all year? Specific examples include the following:

- How can siloed funding streams be combined? How should financing and funding streams be better targeted to historically marginalized populations and communities?

- How should financing and funding streams be better targeted to historically marginalized populations and communities, and how have historic equity goals been successful or fallen short? How should these communities be identified?

- How can multi-year and other long-term investments support ongoing operations, maintenance, services, and other hub activities?

- How can benefit-cost frameworks be modified to reflect the broad scope of potential resilience hub services to the community, and analyze factors that are historically omitted, such as continuity of operations, or strengthening of human adaptive capacity?

- What strategies and platforms can enable knowledge transfer between communities and between practitioners? Focus areas may include, for example:

- Historically underinvested areas

- Rural areas and tribal communities

- Places with limited clean energy

- How do we create replicable community engagement strategies for resilience hub design and shift decision-making to those most affected by disasters?

Many of the applied research questions addressed in other subsections of this report—including, for example, trust and benefit-cost analyses—could be framed to address resilience hubs, and the findings from resilience hubs research can be used to help inform broader analyses in these topic areas.

In addition to the research questions identified, the committee noted several factors that would enable establishing resilience hubs:

- Provide sustained financing for communities to engage with researchers in a continuous way (see section on Partnerships for Equitable Infrastructure Investment).

- Consider communities to be full partners in research, with government agencies or other funders helping facilitate these relationships.

- Create options for co-ownership or community ownership of research projects.

- Provide local data on community demographics, climate, carbon life-cycle analysis, energy, and other dimensions and partner with communities to effectively use these data to make effective risk-informed decisions on resilience hub design and operation.

- Provide funding focused on systemic change, not just pilot projects.

- Prioritize resources for historically underinvested communities to help achieve a basic standard of infrastructure access.

- Ensure relevant organizations, including community-based partners, are engaged to continuously help inform state, regional, and local funding and decision-making strategy on resilience.

- Incorporate traditional ecological science and local expertise and knowledge about population concerns, needs, and priorities.

Community Resilience Planning

Communities can prosper only if they have operational and hazard-resilient buildings and infrastructure systems. Damaged buildings and infrastructure systems interrupt social services, produce soaring economic losses, and require resource reallocation to repair and rebuild the systems. When damage is extensive, the recovery process can be a significant drain on the community and may draw on its resources for years (NIST, 2016). Negative outcomes can compound as communities reallocate resources for maintenance and improvements to repairs and reconstruction, stunting the recovery process, which, if it takes too long, can lead to permanent economic decline and population relocation, as in the case of New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina.

Activities such as prevention, protection, mitigation, response, and recovery are key components of resilience, where resilience is an umbrella concept for these actions and the desired outcome of maintaining and improving restoration of functions and services. While response and recovery activities occur post-event, communities should plan these activities prior to hazard events, including pre-positioning assets to be used once the disaster strikes (Rose, 2017) (see Box 6). Communities may need to adjust pre-event plans for response and recovery, as unique or unexpected events may occur, and it is much easier to adjust existing plans than to create them during the turmoil following a disaster. As climate-sensitive hazards continue affecting lives and livelihoods, neglecting to plan in advance will result in planned failures, with many of these failures occurring in historically disadvantaged and socially vulnerable areas.

BOX 6

Indicators and Metrics to Help with Planning

Indicators and metrics can help identify vulnerabilities and track community resilience over time. For example, a 2016 study reviewed 27 resilience assessment tools, indexes, and scorecards and identified four parameters that researchers have used to distinguish between them—focus (on assets baseline conditions), spatial orientation (local to global), methodology (top down or bottom up), and domain area (characteristics to capacities). The most common elements in all the assessment approaches can be split into “attributes and assets (economic, social, environmental, infrastructure) and capacities (social capital, community functions, connectivity, planning)” (Cutter, 2016).

Researchers have also developed frameworks to connect concepts of resilience to measurable indicators and measures to operationalize the concept of resilience. These frameworks have emerged both as a methodology to study community resilience and as a decision support tool for disaster and adaptation planning. However, reviews by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Community Resilience Program and others (Loerzel and Dillard, 2021; Walpole et al., 2021; Cutter, 2016) have shown that there is a lack of consensus in terms of the theoretical approaches taken, indicators and measures used, data requirements, and spatial scales among the frameworks. To better understand these disparities, NIST constructed an inventory of resilience frameworks (Loerzel and Dillard, 2021; Walpole et al., 2021).

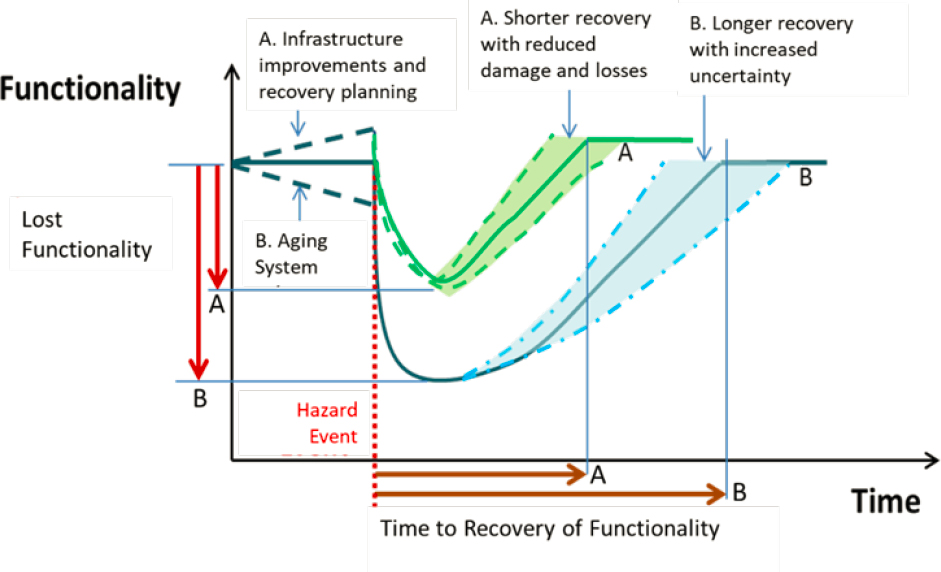

Figure 1 depicts resilience in terms of infrastructure disruption losses over time in relation to the “loss triangle,” the area between system function or output in the absence of disaster compared with the system function or output when a disaster occurs (the entire gray area between the horizontal) “without-disaster” line and the “with-disaster” curve. In the absence of any risk-reduction efforts prior to a disaster, the system will drop to the lowest vertical point in the loss triangle. Robustness is the ability of the system to withstand the shock and avoid total failure. Pre-disaster actions (ex ante), commonly referred to as mitigation, reduce the initial shock in terms of both property damage and business interruption and reduces time to recovery. Actions taken once the disaster strikes (ex post) cannot reduce property damage, but they can reduce business interruption. Such actions are sometimes referred to in the literature according to a narrower definition of resilience, based on the Latin root of the term, meaning to “bounce back.” However, it is important to note that most analysts view resilience as a process, whereby post-disaster resilience capacity can be built up ahead of time by such actions as purchasing backup electricity generators, stockpiling critical materials, or practicing emergency drills, though these resilience “tactics” are not actually implemented until the disaster strikes (Rose, 2017).

SOURCE: NRC, 2011.

Figure 2 provides further insight into important aspects of infrastructure resilience. Case A illustrates how pre-event activities, such as mitigation and recovery planning, can lead to a shorter recovery time for infrastructure system functionality and recovery when there is increased capacity to resist or avoid damage. When infrastructure systems age through inadequate maintenance and continued degradation, as shown for Case B, the damage, loss of functionality, and time to recovery of system functions can be much greater. Additionally, as depicted by the shaded area between the dashed lines, there is likely to be a relative increase in uncertainty for the recovery of functionality, due to greater damage and disruptions.

Therefore, for infrastructure services and operations, the most effective approach is to take mitigation and planning actions before a hazard event to minimize the need for emergency response and recovery. For example, retrofitting facilities, improving land use and zoning regulations, adopting and enforcing building codes, and installing flood barriers can improve infrastructure performance and reduce damage and losses. Additionally, as indicated by Case A in Figure 2, immediate and targeted response actions following a hazard event can substantially reduce the recovery time and accelerate recovery (Xie et al., 2018; Zobel, 2014).

Improved infrastructure performance also leads to reduced business interruption and social impacts. An important consideration regarding mitigation for existing infrastructure is the cost of the improvements relative to the increase in performance they produce. For some facilities, the decision may be to move critical functions to another location to reduce vulnerability despite hazard threats, or to plan on rebuilding elsewhere after a hazard event. Major studies of the benefits of mitigation have found that the benefits exceed the costs by at least a 4-to-1 ratio (MMC, 2005, 2019; Rose et al., 2007).

SOURCE: McAllister, 2013; NIST, 2016.

The community population, businesses, and organizations also need similar resilience activities. Pre-event planning and mitigation activities are essential to accelerating post-event response and recovery. The quality, extent, and timeliness of response activities can greatly increase the recovery of functionality across a community (FEMA, 2011; NIST, 2016). However, policy makers often give precedence to infrastructure because many infrastructure services, especially electricity and water, are considered community lifelines that are needed for survival (FEMA, 2019). Other infrastructure such as transportation and communication are key to emergency response and the recovery process.

As the nation moves forward, it needs better methods to track and measure the impact of infrastructure performance and investments (Preston et al., 2022). Resilient performance of infrastructure should also support equitable access to community services, such as safe housing, transportation, utilities, health care, and education. In addition, mitigation and recovery processes related to hazard threats need to consider underrepresented groups and underserved communities.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions pertaining to community resilience planning:

- What are the negative compounding outcomes that stunt the recovery process and require resource reallocation by communities? When do they lead to permanent economic decline and population relocation?

- What federal standards are needed to ensure accountability?

- What measures and indicators are needed to help communities track progress toward improving resilience and equity and prioritize infrastructure plans and investments?

- How have pre- and post-event resilience strategies, such as mitigation, redundancy, and relocation, as well as government policies, improved outcomes for individuals, communities, and regions? And which individuals and communities are left out of these benefits?

- Does improved resilience at one scale (e.g., neighborhood, community, region) adversely affect resilience at another scale?

- What has been the performance record of mitigation and other resilience activities in terms of individual and cross-community benefits? How do expected and actual benefits compare?

- What planning and funding strategies are needed for local, state, and federal stakeholders to ensure that affordable housing is not disproportionately located in neighborhoods or communities at higher risk of damage and loss of services?

- How can renters and tenants be included in the decision process for prioritizing resilience and equity improvements to existing housing and supporting infrastructure/services as well as in post-disaster housing? How do we prevent further housing instability and homelessness following a disaster?

- How can we understand and build resilient infrastructure as integral systems that meet the needs of communities in a comprehensive manner and with decisions based on equitable access?

- What are the effects of transportation and its disruption on neighborhoods and micro-movements of population as revealed by micro-data on individual households, businesses, and institutions? How can transportation systems address mobility as well as safety, accessibility, walkability, drainage, resource conservation, and health benefits in an equitable way?

- As transportation systems become more automated and integrated, what are the effects on housing, employment, commuting, and metropolitan transport choke points regarding the interface (nodes, areas, links, and connectivity) between long-distance (long-haul) freight transport and local (within metro areas) distribution?

- Has the COVID-19 pandemic created a tipping point or will access in urban areas be increasingly dominated by mass transit as it was in the years leading up to the pandemic in some parts of the country, such as the East Coast? Can transportation

- risks be balanced with less expensive post-disaster coping mechanisms such as telework and shifting business locations?

- How can we rethink redundancy as a major strategy for coping with risks to infrastructure performance in spite of improvements in efficiency?

- How can we understand and build resilient transportation infrastructure as integral systems that meet the needs of communities in a comprehensive manner and with decisions based on not only mobility but also safety, accessibility, walkability, drainage, resource conservation, and health benefit?

In addition, the committee noted several factors that would enable community resilience:

- Provide communities with examples of successful community resilience planning and recovery, especially those that encourage public participation and inclusiveness, including accessibility; resilience planning should be co-created with communities.

- Provide communities with quantitative community resilience planning tools that support informed decision-making.

- Incorporate emergency response and functional recovery in infrastructure planning investments to become resilient and to effectively address the current and future challenges resulting from climate change, aging infrastructure, land use, and so forth.

- Develop a better understanding of resilience and equity gaps and related problems using data that are consistently available for analysis and metrics to track progress (or lack thereof).

- Consider mitigation and preparation strategies that are focused on the most vulnerable communities.

- Plan for the higher cost of recovery in vulnerable areas of communities that are expected to have greater levels of damage and losses due to past planning and funding actions as well as due to lack of planning and funding investments.

- Improve preparedness and emergency response logistics to minimize the loss of community functions after a disruptive event. Improve recovery times to reduce adverse impacts on various components of communities (households, businesses, institutions).

Integrated Multi-Benefit Solutions

Silos of expertise, training, and project delivery lead to highly competent solutions that may discount impact and opportunities adjacent to and outside of that silo. This leads to single-problem, single-fix approaches that do not capture broader community benefits that could maximize the value of infrastructure investments to local communities. Achieving smart integrated solutions needs to be done at the pre-design phase of infrastructure development before narrow-focus solutions are designed and funded. Infrastructure providers can find this challenging when they have single-purpose funding streams. Yet when equity and maximizing community value is the intent, then new norms need to be enabled to break down silos. Additionally, having a convener or moderator, who knows and understands the community, during and before the pre-design phase may increase the benefits of the infrastructure development and investments and achieve multi-benefit solutions.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions pertaining to integrated multi-benefit solutions:

- How can communities use broad-based and inclusive planning to maximize economic, environmental, and social value by working together at the pre-design phase to make infrastructure investments address historic disinvestment in BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities?

- What systems-based models can be integrated into infrastructure investments to better understand local values, map assets, and identify alternatives?

- How do we broaden project-funding streams to ensure that they can provide multiple community benefits?

- How do we redesign funding structures to include the resilience component?

- What are the barriers to integrated funding and regulatory solutions?

Some of these concepts will be discussed further in the upcoming section on benefit-cost analyses.

In addition to the above research questions, the committee noted factors that would enable the development of integrated multi-benefit solutions including:

- Condition federal funding to encourage and prioritize broad-based and inclusive approaches to community investments that help communities find fair, equitable, and inclusive solutions for large infrastructure projects.

- Require the design phase of infrastructure solutions to be measured against equitable outcomes and include community stakeholders prior to disaster or in the mitigation phase of resilience.

- Include community stakeholders in the post-disaster recovery phase.

Interdependence of the Built and Natural Environments

The built and natural environments are connected to the health of communities. Focusing on good practices for communities that disastrous events devastate disproportionately could lead to better long-term community benefits. Examples of these benefits include health-related outcomes from physical activities, social engagement, mental health, perceptions of crime, and road traffic collisions. Research has associated these benefits with built environment planning activities such as enhanced walkability, compact neighborhood design, enhanced connectivity, and a safe and efficient infrastructure (Bird et al., 2018).

Exposure to natural environments and even vegetation in cities can enhance physical and emotional health. One study, for example, found that a 20-minute natural experience caused physiological biomarkers of stress to fall by more than 20 percent (Hunter et al., 2019). Other research has shown that tree cover for elders in care facilities was associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Browning et al., 2019). Several studies, however, found significant race-based inequity in urban forest cover (Lin et al., 2021; Locke et al., 2021; Watkins and Gerrish, 2018; Watkins et al., 2017).

Natural watersheds provide potable water and provide soils and habitats that support food and fiber for human uses. Functioning natural systems provide protection for the built

environment. For example, coastal salt marshes function as natural buffer zones and provide protection for coastal communities by attenuating storm surge and wave action. Mountain forests with healthy soils can protect against downstream floods through water storage, erosion control, and increased surface area evaporation (Markart et al., 2021).

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions pertaining to the interdependence of the built and natural environments as they relate to equitable and resilient infrastructure investments:

- How can we investigate, understand, and apply function and design relationships between neighborhood housing and access to natural areas and open space?

- What performance measures could we apply broadly to quantify and accelerate adoption of urban greening programs that link energy conservation, urban heat islands, and equity?

- How can we measure interrelationships between the built and natural environments to foster investment that brings about optimal and equitable conditions for underserved communities?

- How can we integrate the concept of disaster mitigation (pre-disaster) versus post-disaster (resilience) with equity community voices to support investment decisions in the built environments?

- What are successful case studies where urban areas have enhanced and restored natural environments that provide food, fibers, and water and serve as a barrier to mitigate natural hazard risk?

In addition, the committee noted two factors that would enable better connections between the built and natural environments:

- Integrate community stakeholders that represent voices from the community who will push for designs and planning that will support equitable outcomes.

- Understand the spillover effects on investments in communities with planned dividends to the community and to the environment. Investments can have unintended consequences and, if planned accordingly, could benefit and support equitable communities.

Minimum Code Requirements

Communities consist of buildings and infrastructure that can range from new construction based on modern codes to construction that is more than 100 years old. In addition, some hazards, such as floods and earthquakes, vary over the geography of communities. This range in construction quality, standards, and exposure to hazards leads to uneven performance and damage levels across communities, and community resilience and equity planning can address this uneven performance.

National building codes and standards have been developed to ensure minimum requirements for life safety and public welfare. The minimum requirements allow flexibility for designers and communities to tailor additional requirements for local purposes and issues. At the same time, minimum standards set by best practices may not reflect a community’s expectation

for resilience. In addition, to be effective, states and communities need to adopt the national codes and standards. However, approximately 60 percent of local jurisdictions have not adopted building codes (FEMA, 2022). Failure to adopt and implement current codes and standards exposes communities to disproportionate impacts, as substantial damage may occur for hazard events that would normally cause minor, if any, damage with proper design and construction.

For existing construction, retrofits and renovations are more challenging to address. The International Existing Building Code addresses requirements for modifications to existing buildings. Depending on the condition of an existing facility, it may or may not be possible to meet current code requirements for new buildings. Mitigation measures that can significantly reduce vulnerabilities to damage need to be evaluated for effectiveness relative to their costs. For example, housing retrofits and renovations can raise costs that disproportionately impact low-income communities, Indigenous people, and communities of color, particularly for tenants.

Model codes and associated standards are prescriptive in nature, where compliance with specified requirements infer a minimum level of acceptable performance. When code requirements do not meet the needs of a project, building officials can approve alternative methods. Alternative methods, such as performance-based design, can use specified performance objectives to explicitly address project requirements. A key aspect of resilient infrastructure, though, is compliance with national regulations, codes, standards, and best practices (McAllister et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). Given the lack of code adoption and the effects of aging and lack of maintenance across the nation (ASCE, 2021), simply meeting or exceeding minimum requirements would improve infrastructure performance. A 2019 study (NIBS, 2019) examined five sets of mitigation strategies and found that society could obtain a benefit-cost ratio of 11 to 1 by adopting the 2018 International Residential Code and International Building Code, the model building codes developed by the International Code Council (also known as the I-Codes), versus codes represented by 1990-era design.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions pertaining to minimum building codes as they related to equitable and resilient infrastructure investment:

- What do states and communities need to understand the value of adopting and administering code and standards as a foundational aspect of short- and long-term economic benefits and resilient infrastructure with reduced damage and losses?

- What incentives exist to encourage communities to specify requirements beyond code -minimum performance?

- How do codes and standards for new construction and upgrades to existing facilities affect community equity and resilience?

- What are the disparate effects of updating existing buildings on landlords and tenants regarding safety, health, and affordable housing?

- What are the impacts on community equity and resilience of failing to adopt codes and standards on resilience?

- What is the role of performance standards versus prescriptive code requirements for achieving resilient and equitable outcomes?

- What data and analyses are needed to address functional recovery in infrastructure design practice?

In addition, the committee noted the following 3 factors that would enable better use of building codes to enhance community resilience:

- Provide access to local infrastructure data, such as codes and history, flood maps, appraisals, records, and drawings.

- Develop codes and standards that support resilient performance and equitable services for new and existing infrastructure.

- Build stakeholder understanding of local resilience goals/needs relative to those achieved by meeting minimum code requirements.

3. INNOVATIONS IN ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

Traditionally, public funds finance infrastructure investments, but public deficits, the inability of the public sector to deliver efficient investment spending, and a lack of political will have in many communities led to governments reducing the level of public funds they allocate to infrastructure. Discussions at the workshop made it clear that research needs to develop new analytical tools that can demonstrate the benefits of public investment in resilient and equitable infrastructure development and that would lead to developing new mechanisms for financing resilient and equitable infrastructure.

Innovative Financing for Equitable Infrastructure Development

As a key driver for sustainable growth, infrastructure constitutes a vital pillar of fiscal stimulus to provide economic recovery, particularly in a post-COVID-19 period. It will also serve as a crucial component of the transition to a low-carbon economy (Gaspar et al., 2020). As such, there is an opportunity to increase the magnitude of investment in infrastructure. However, efforts to expand infrastructure investments must complement, in equal measure, considerations to improve the quality of these investments, including by ensuring that infrastructure is equitable and does not inadvertently exacerbate inequality.

Promoting quality infrastructure2—infrastructure that is well planned, efficiently implemented, resilient, equitable, and sustainable—is an essential enabler for achieving sustainable growth, and more globally, achieving the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals and national greenhouse gas mitigation contributions under the Paris Agreement. The focus on quality has taken on greater resonance during the COVID-19 crisis, highlighting the need to “build back better” by maximizing the quality of infrastructure assets at the earliest stages of the project life cycle to improve resilience to, and reduce the costs of, future shocks, including climate change (Rozenberg and Fay, 2019).

Economic stimulus will serve as a critical lever to ensure infrastructure investments are of a high quality, sustainable, and equitable. Increased climate-resilient infrastructure

___________________

2 Quality infrastructure is a concept embodied by the G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment to raise awareness of the quality dimensions of infrastructure in emerging markets, but it is equally relevant in the United States.

development can also reduce the risk of physical stranded assets, diminish disruptions in services, and create opportunities to meet infrastructure service needs for all communities, particularly the most vulnerable, in a more efficient way. As global markets recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, there will be an increased need to spend public funds intelligently3 and quickly, which can work at cross-purposes, and incentivize private investments.

Public funding can play an important and sometimes driving role in ensuring infrastructure is both climate resilient and equitable. Thus, public financing is a particularly attractive source of capital whose value simply exceeds the investment dollars from the public balance sheet. Innovation in not only how these funds are invested but also how these funds drive equitable and climate-resilient outcomes will be critical.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions pertaining to innovative financing for equitable infrastructure development.

- What is the range of public finance for climate-resilient infrastructure that includes mechanisms, incentives, or other measures, including equity requirements, to ensure that projects it supports are equitable?

- Where they exist, how do these measures ensure that such projects are equitably developed? Which stakeholders were engaged, and what was the process to ensure that the end users defined equity?

- What are the range of public finance options for community equity and resilience that also focus on climate-resilient infrastructure?

- How are these public financing programs supporting climate objectives in addition to equity and community resilience, if defined more broadly than climate resilience?

- Where they exist, how are measures that ensure climate resilience developed?

- What assessments were done to understand climate vulnerability, and were these assessments considerate of equity aspects?

- What are the specific financial mechanisms for equitable infrastructure development, such as grants, loans (concessional or commercial), guarantees (concessional or commercial), and equity/financial equity of public financing programs?

- What are the terms and conditions of such financing? Are these terms and conditions equitable in a way that does not disproportionately disadvantage vulnerable and historically underinvested communities?

- Do the terms and conditions allow for greater access to financing or less access to finance?

- How effective are these mechanisms in the context of equitable outcomes?

- What is the relative cost to accessing these funds for equitable and climate-resilient outcomes, as measured in time spent to apply for funding, the volume of financial support provided, and the ability of communities to leverage funding?

- How innovative are these financial mechanisms, as measured by (1) the uniqueness of the terms and conditions, (2) the connections to nonfinancial impacts and co-benefits (e.g., measures of improved equity or improved “resilience”), and (3) their complexity.

___________________

3 Inefficiencies in public infrastructure investment processes have shown to waste an average of 30 percent of public resources (Schwartz et al., 2020).

- What is the role of wrap-around funding—a collaborative, team-based funding approach to service and support planning—and financing in mitigation, recovery, and other aspects of risk reduction?

In addition, the committee noted the following 3 factors that would enable innovative financing for equitable infrastructure development:

- Map federal, state, and local public funding sources for both climate-resilient infrastructure and equity goals, including the processes that these sources undertook to ensure equity issues are well developed.

- Provide localized data and information about vulnerability beyond climate vulnerability.

- Ensure broad representation in research and in interpreting and assessing the research outcomes before developing recommendations about whether and how innovative financing sources can better enable climate-resilient, equitable outcomes.

Benefit-Cost Analysis

Benefit-cost analysis is a decision-making tool that policy makers use primarily for evaluating certain public-sector investments, such as infrastructure construction when ordinary markets do not exist, or where markets cannot achieve efficient outcomes, or, increasingly, where desired outcomes extend beyond economic efficiency (Boardman et al., 2018).4 Policy makers also use benefit-cost analysis to evaluate investment infrastructure protection against disasters (mitigation), coping with ramifications of infrastructure damage and loss (resilience), and decisions regarding reconstruction alternatives (including “building back better”). Increasingly, decision makers are evaluating infrastructure investment as a major strategy to cope with climate change impacts, as in the construction of barriers or elevating structures to protect against sea level rise. In fact, benefit-cost analysis studies have found that mitigation against disasters yields a benefit-cost ratio of at least 4 to 1 for historical cases (MMC, 2005, 2019; Rose et al., 2007) and as much as 11 to 1 for advanced building codes (MMC, 2019). Moreover, a survey-based study that examined resilience responses by businesses to input supply disruptions in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey found an average 4.5-to-1 benefit-cost ratio in reducing potential lost revenue (Dormady et al., 2022). As applied to infrastructure funding, benefit-cost analysis can on occasion lead to inequitable outcomes, which can include discounting future generations and inappropriately valuing or omitting non-monetizable community values, such as public health, community ownership, or resilience when that is not the primary objective (see Box 7). Benefit-cost analysis also omits equity considerations, such as failing to account for historic disinvestment in low-income communities, Indigenous communities, and communities of color. The tendency to assess the cumulative benefits and costs of projects, rather than the distribution of these benefits and costs, frequently limits these

___________________

4 This is in contrast to private companies making capital investments or decisions on investments in financial instruments, where considerations such as profits or rates of return represent the “benefits.” In benefit-cost analysis, benefits are interpreted broadly to include all benefits to society, even beyond those that accrue to the individual investor. This is also the case for the cost side of the ledger. Nongovernmental organizations and philanthropic organizations typically use broader concepts of benefits and costs as well.

analyses. In addition, benefit-cost analysis is often used for siloed analyses, and outcomes that depend on how the user selects inclusion and exclusion criteria. For example, the multi-benefit solutions discussed in an earlier section of this report would require a more inclusive benefit-cost framework than is frequently used for investment decisions.

Based on the presentations, examples, and research opportunities discussed in this workshop, the committee identified the following applied research questions pertaining to benefit-cost analysis as applied to resilient and equitable infrastructure development:

- How can we include distributional considerations in benefit-cost analysis to analyze equity, social justice, and other broad societal goals?

- How can we adapt benefit-cost analysis to account for difficult-to-monetize outcomes, such as resilience, public health, and equity?

- Are there alternative decision analysis approaches to benefit-cost analysis to evaluate resilient infrastructure investments?

- What adjustment to benefit-cost analysis would better incorporate benefits to future generations?

In addition, the committee noted factors that could improve benefit-cost analysis as applied to resilient and equitable infrastructure development including:

- Further explore equity considerations during recovery from disasters.

- Enhance public participation of all stakeholders in risk-reduction decisions.

- Improve decision support tools, such as FEMA’s benefit-cost analysis toolkit, to include equity considerations.

BOX 7

Approaches to Measuring Intangibles in Benefit-Cost Analysis

One approach that broadens the scope of benefit-cost analysis is the “triple-dividend” of disaster risk reduction (Surminski and Tanner, 2016). This approach emphasizes that the direct intended benefits of hazard mitigation may never be realized if no disaster occurs, a condition that often biases decision makers against mitigation. To address that shortcoming, this approach adds two additional categories to ordinary direct benefits. One is the reduction in uncertainty that comes from investment in mitigation, which promotes an improved business environment and further investment more generally. The other refers to joint product effects, which can be extensive if properly devised. For example, green stormwater infrastructure serves mobility, safety, drainage, and water conservation needs.

Incorporating emergency response and disaster recovery in transportation planning investment is critical for all communities to become resilient and effectively address the current and future challenges resulting from climate change, other disasters, and aging infrastructure in general. Broader joint products in relation to equity and social justice fit into the triple-dividend framework as well.

Another issue with benefit-cost analysis is that it values the benefits of resilient infrastructure investments for future generations much less than current ones because it accounts for the time value of money. For example, a $1 million investment today, even at a low discount rate of 3 percent, is only worth $52,000 in present value terms according to the traditional methodology. There are several alternative approaches to the inappropriate alternative of using a zero-discount rate, such as channeling some of the current benefits of a project in its early years