Review of Four CARA Programs and Preparing for Future Evaluations (2023)

Chapter: Appendix B: Contracted NORC Report

This page intentionally left blank.

Table of Contents

Methodological Approach and Data Collection

Selection and Recruitment of Interview Participants

Grant Program Impacts and Sustainability

Recommendations for Future Policy and Programming

Follow-Up Interview Email for PI/co-PI as Respondent

Follow-Up Interview Email for Other Program Team Member

Executive Summary

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) are conducting a consensus study to understand the progress made on Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-funded Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) grant programs to reduce opioid-related harm and promote recovery from substance use disorders. Thus far, NASEM research has resulted in two reports. For the third and final report, NASEM seeks to understand the factors that impede or facilitate the implementation and the evaluation of four specific SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs to support NASEM toward making conclusions about the effectiveness of achieving program goals and recommendations to Congress for the future of the federal government’s response to the opioid crisis.

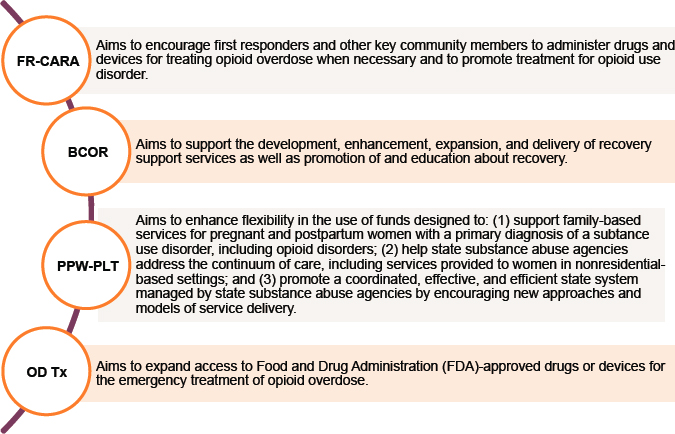

The four programs are: Building Communities of Recovery (BCOR), First Responder Training (FR-CARA), Improving Access to Overdose Treatment (OD Tx), and Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women Pilot (PPW-PLT). The FR-CARA and OD Tx programs represent grantees that receive resources and support from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) at SAMHSA, while BCOR and PPW-PLT grantees are supported by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT).

In January 2022, NASEM contracted with NORC to organize and conduct virtual, in-depth interviews with staff at organizations that had received CARA grant funding in fiscal year (FY) 2017 or FY2018 to implement and/or evaluate these four programs. The interviews gathered information about the following:

- The goals of implementing grantees, and how they fit within the stated goals of the SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs;

- The process of implementing each organization’s SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program, and factors contributing to successes and challenges;

- How each grantee organization evaluated its SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program, with a specific focus on the types of data collected that are related to process and outcome metrics;

- The intended and unintended impacts of the grantee organization’s SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program on the population served, organizations involved, and the broader community; and assess any efforts related to program sustainability; and

- Grantee recommendations for future programs and evaluations.

Key Findings

- Most grantees across the CSAP And CSAT programs were engaged in related activities before receiving SAMHSA funding, noting that the CARA grant allowed them to expand pilot programs or work underway. As a result, they expanded target populations or geographic service areas and increased the number of people eligible for services. At the same time, grantees elaborated on the broader impact their CARA grant program could have on individual attitudes and public perception on overdose and recovery by highlighting the need within their community.

-

Grantees identified successes while implementing their CARA grant programs, including:

- Establishing new partnerships and/or strengthening existing partnerships.

- Reducing stigma toward opioid misuse, overdose, prevention, and recovery in their communities through education and trainings.

- Increasing capacity to serve more clients in the case of PPW-PLT and FR-CARA grantees, by expanding the use of grant funds beyond what they had originally proposed.

- Creating data dashboards or repositories to facilitate data sharing among CSAP grantees and interested parties, such as community members, partnering organizations, and local government agencies.

- Transitioning care successfully from in-person to virtual during the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to cost savings and expansion of people who could attend trainings and receive services.

-

Grantees encountered several challenges while implementing their CARA grant programs, including:

- Several CSAT grantees and one CSAP grantee attributed delayed program start-up due to SAMHSA funding delays.

- Struggles with forming partnerships with emergency departments (EDs) and/or Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) due to limited availability of staff and physicians at these sites.

- Inability to collect follow-up data from both clients and individuals who attended trainings and/or events facilitated by grantees.

- Dealing with stigma toward opioid misuse, overdose, prevention, and recovery among those responsible for administering overdose prevention medications as well as people at risk of experiencing an overdose.

-

- Several CSAP grantees noted staff capacity constraints, as well as limited access to data, including treatment outcomes, and data elements beyond those available in electronic health record (EHR) systems.

- Many CSAT grantees identified a lack of resources for clients, including non-clinical support services, such as housing, transportation, internet access, cell phone data, and medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder.

- Coping with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as making a transition from in-person to virtual care.

- Most grantees contracted with an external entity to evaluate their program. Grantee evaluation efforts focused mostly on SAMHSA requirements, specifically the web-based reporting tools Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) tool and Division of State Programs-Management Reporting Tool (DSP-MRT). Several grantees, mostly from CSAT programs, reported disliking the tools due to concerns over an emphasis on quantity over quality and a mismatch with the required intentions or activities of the grant.

- To advance program sustainability, some grantees reported applying for additional federal, state and/or local funding to maintain internal supports (e.g., staff) and processes (e.g., trainings). Identifying additional funds to cover the cost of overdose prevention medications, however, was seen as a bigger hurdle for CSAP grantees.

-

Grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs had several recommendations for future policy and programming including:

- Improving SAMHSA’s interaction with grantees, for example, through consistent contact and communication with SAMHSA project officers.

- Increasing SAMHSA efforts to foster cross-grantee collaboration so that grantees can learn from one another and exchange ideas for overcoming challenges.

- More flexibility within SAMHSA-funded grant requirements to adapt to the changing environment, especially considering the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the unique needs of different states, jurisdictions, and/or municipalities.

- SAMHSA grants no longer stipulating a funds match as noted by BCOR grantees.

-

Grantees suggested several areas to focus future federal government funding, including:

- Outreach services.

- Harm reduction services.

- Nonclinical recovery support services, including, housing, transportation, social services, basic needs, medications, and coverage/support for client’s family and caregivers.

- Providing funding for longer implementation timeframes.

Introduction

Background to the Study

In 2016, lawmakers passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA; P.L. 114-198), which included several grant programs to help reduce opioid-related harm and promote recovery from substance use disorders.1 As part of this law, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) were commissioned to convene an expert Committee to issue a series of three reports over five years evaluating the success of four specific grant programs funded and administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2 Grantees comprised 86 different organizations or partnerships in the Building Communities of Recovery (BCOR), First Responder Training (FR-CARA), and Improving Access to Overdose Treatment (OD Tx) programs; and six states in the Treatment for Pregnant and Postpartum Women Pilot (PPW-PLT). The FR-CARA and OD Tx programs represent grantees that receive resources and support from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) at SAMHSA, while BCOR and PPW-PLT grantees are supported by the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT). The first two reports were completed and published in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

In the first report, Measuring Success in Substance Use Grant Programs: Outcomes and Metrics for Improvement,3 the Committee offered recommendations to SAMHSA about existing program monitoring and reporting tools used by grantees, including the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) tool, Division of State Programs-Management Reporting Tool (DSP-MRT), and tools unique to individual grantees. The Committee also recommended new metrics and outcomes for consideration while recognizing grantee limitations (e.g., staff and resources). For example, the Committee recommended that SAMHSA support prevention grantees (FR-CARA and OD Tx) in collecting and reporting data on the number of overdose survivors who initiate and are engaged in evidence-based opioid use disorder treatment. In relation to the treatment and recovery grantees (BCOR and PPW-PLT), the Committee suggested that SAMHSA implement and/or develop additional data-collection tools that assess alcohol and drug use and recovery in a more realistic and comprehensive manner.

For the second report, Progress of Four Programs from the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act,4 the Committee gathered data (work plans, evaluation plans, and progress reports) from SAMHSA about each of the grant programs in an effort to assess progress toward achieving program objectives. The Committee focused on grantee planning and implementation steps (e.g., hiring, training staff, relationship-building) and program outcomes (e.g., client-based substance use outcomes, naloxone distribution and use, public education, trainings). In addition, the Committee evaluated materials to determine whether grantees made progress toward the required and allowable activities identified by SAMHSA for each grant program. The Committee concluded that, while there had been some progress in planning and implementing the CSAP and CSAT grant programs, the identifiable impacts on substance use disorders and on advancing systems change in substance use prevention, treatment,

and recovery could not be determined. In addition, the report discussed several of the limitations encountered by the Committee in reaching these conclusions and proposed approaches and data sources that might be helpful in the preparation of the third report. These ideas included, among others, interviews with key program staff to generate supplemental data on lessons learned and program effectiveness.

Research Objectives

To support the work of the Committee for the third and final report, NASEM contracted with NORC at the University of Chicago (NORC) in January 2022 to organize, conduct, and analyze virtual, in-depth interviews with individuals from grantee organizations that had participated in the implementation and/or the evaluation of one of the four SAMHSA-funded CARA programs awarded in FY2017 or FY2018. Insights from these interviews will inform NASEM and the Committee’s conclusions about grantee progress in achieving program goals and the Committee’s recommendations to Congress for the future of the federal government’s response to the opioid crisis.

Specifically, the interviews gathered information to address the following research objectives:

- The goals of implementing grantees, and how they fit within the stated goals of the SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs;

- The process of implementing each grantee organization’s SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program, and factors contributing to successes and challenges;

- How each grantee organization evaluated its SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program, with a specific focus on the types of data collected related to process and outcome metrics;

- The intended and unintended impacts of the grantee organization’s SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program on the population served, organizations involved, and the broader community, and assess any efforts related to program sustainability; and

- Grantee recommendations for future programs and evaluations.

Report Purpose and Structure

This report presents findings from an analysis of interviews with program administrators at grantee organizations implementing and/or evaluating SAMHSA-funded CARA programs. Organized by the five previously cited research objectives, the analysis aims to understand factors that impeded or facilitated grantees’ implementation and evaluation of their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs.

The report is organized as follows, with the next section discussing the study methodology, including details on respondent outreach, the sampling and recruitment of interview participants, data collection and analysis, and study limitations. We then describe the key findings from the interviews, organized by the five research objectives. The last section concludes with a high-level summary of the study’s

methodology and key findings. Multiple appendices are included and provide additional details about the recruitment process and interview protocol.

Methodological Approach and Data Collection

As previously noted, the study’s goal is to supplement information previously reported to SAMHSA on the progress of CARA grant programs. To accomplish this goal, NORC was tasked with conducting individual, semi-structured interviews with program administrators at grantee organizations that had participated in the implementation and/or the evaluation of one of the four SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs (i.e., FR-CARA, BCOR, PPW-PLT, and OD Tx; see Exhibit 1 for a brief description of each program) awarded in FY2017 or FY2018. The study received approval from the NASEM and NORC institutional review board.

Selection and Recruitment of Interview Participants

Selection of Interview Participants. NORC selected 45 grantee organizations across the four CARA programs: FR-CA, BCOR, PPW-PLT and OD Tx. As shown in Exhibit 2, the PPW-PLT and OD Tx programs are small, with each comprising a total of six grantees awarded in FY2017 or FY2018. To maximize representation of the smaller programs, the full universe of 12 PPW-PLT and OD Tx grantees was selected for the study.

NORC purposively sampled the larger FR-CARA and BCOR programs to select a sample of 33 grantees, maximizing diversity across region of location/operation (Midwest, Northeast, South, West, or Territory), urbanicity (rural, urban, or both), grant award year (2017 or 2018), and organization type (city, county, state, tribal, territory or university). NORC received from NASEM a list of grantee

___________________

1 For a more detailed description of the required and allowable activities of the CARA grant programs, please see:

FR-CARA Funding Opportunity Announcement SP-17-005.

BCOR Funding Opportunity Announcement TI-17-015.

PPW-PLT Funding Opportunity Announcement TI-17-016.

OD Tx Funding Opportunity Announcement SP-17-006.

organizations funded by SAMHSA under the CARA programs, along with descriptive information about each organization that informed the sampling strata for the FR-CARA and BCOR programs. Of these 33 grantees, 19 were from the FR-CARA program and 14 from the BCOR program. FR-CARA and BCOR grantees were distributed in the sample as follows:

- 24 percent were located in mostly rural areas, 40 percent were located in urban areas, and for 36 percent their service areas spanned both urban and rural locations;

- Most grantees (30%) were located in the South, while the Midwest and Northeast comprised equal proportions of grantees (27%), and the rest were categorized as West or a territory;

- Just over half the sample received funding in 2018 (52%) while the remainder received funding in 2017; and

- 74 percent of the FR-CARA grantees sampled identified as a city, county, or state governmental entity, with the remainder of FR-CARA grantees identifying as either a tribal, territory, or university organization. BCOR grantees included recovery community organizations.

Exhibit 2: Population of SAMHSA-funded CARA Grantees, by Program

| CARA Program | Universe of Grantees | Selected for Interview Recruitment |

|---|---|---|

| FR-CARA | 48 | 19 |

| BCOR | 26 | 14 |

| PPW-PLT | 6 | 6 |

| OD Tx | 6 | 6 |

| TOTAL | 86 | 45 |

Recruitment of Selected Interviewees. Recruitment of selected participants occurred between April 13–May 27, 2022. NASEM project staff provided NORC with contact information for all principal investigators (PIs) and/or co-principal investigators (co-PIs) at grantee organizations. Using this information, NORC project staff conducted an initial email outreach to PIs and/or co-PIs at each of the 45 selected grantee organizations, providing information about the study purpose, interview discussion topics, and interview duration and requesting participation in the interview. In that same recruitment email, NORC project staff also requested the PI/co-PI to identify the person(s) (no more than three) at the grantee organization who they deemed would be most suitable to participate in the interview (i.e., involved in both the implementation and evaluation, able to speak to a broad set of discussion topics, including: (1) program goals and activities, (2) implementation success and challenges, (3) program evaluation and sustainability and, (4) future funding recommendations). NORC included Information about participant confidentiality to reassure interviewees that neither they nor their organization/agency would be made known to SAMHSA, the National Academies, or any staff outside of the NORC study team. Appendix A contains a copy of the initial outreach email. As part of the initial outreach, NORC project staff also attached a frequently asked questions (FAQs) document for review prior to consenting to participate in the study. Appendix B contains a copy of the FAQs. Reminder emails (up to three) were sent to nonrespondents.

The appropriate individuals (PIs and/or co-PIs, or others identified) from grantee organizations who consented to the interview received a follow-up email from NORC project staff for scheduling the discussion at a convenient date and time. In this follow-up email, NORC project staff also asked participants whether they preferred to have a telephone or a video interview. The follow-up email also contained information about participant rights, participant confidentiality, data storage and security, and planned data destruction. Appendix A contains a copy of the follow-up email.

As shown in Exhibit 3, of the 45 grantee organizations that were invited to participate, interviews were conducted with individuals from 22 organizations. The final number of interviews was based on the number of grantees that agreed to participate within the five-week recruitment window that included the initial outreach, reminders, and scheduling follow up.

In general, the final interviewee pool was representative of the universe of grantees with respect to urbanicity, grant award year, and organization type. The one difference identified was that most FR-CARA and BCOR grantees included in the final interviewee pool (33%) were located in the West, in contrast to the sample of grantees that were mostly concentrated in the South.

Exhibit 3: Final Interviewee Pool, by Program

| CARA Program | Completed Interviews |

|---|---|

| FR-CARA | 9 |

| BCOR | 6 |

| OD Tx | 4 |

| PPW-PLT | 3 |

| TOTAL | 22 |

Data Collection

Instrument Development. The NORC team collaborated with the Committee and NASEM on the development of a semi-structured interview guide that would meet the objectives of this study. Exhibit 4 presents the sections and main topics covered in the interview guide. A full copy of the interview guide is available in Appendix C.

Exhibit 4: Interview Guide Layout

| Section | Description of Topics |

|---|---|

| Participant Background |

|

| Grant Program Goals |

|

| Grant Implementation Process |

|

|

|

| Grant Evaluation Process |

|

| Grant Program Impacts and Sustainability |

|

| Recommendations for Future Policy and Programming |

|

Interview Process. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the NORC team virtually using the Zoom platform from April 25–June 9, 2022. Each interview lasted up to an hour and was audio-recorded with the respondent’s consent. A few interviews were group interviews, but no more than three individuals at a grantee organization were allowed to jointly participate in an interview. Interviewees did not receive any compensation for their participation.

Each discussion was facilitated by two NORC project staff, with one serving as the interviewer and the other as the notetaker. Interviewers and notetakers used the written protocol, developed in collaboration with the Committee and NASEM, that included clear and concise instructions as well as suggested probes to help guide conversations with participants.

Before starting the interview, each interviewer orally reviewed consent protocols with each participant to ensure they understood the purpose, risks, and benefits of their participation. The notetaker documented in the interview notes whether oral consent was granted. Participants were also told that, following the interview, they could receive an electronic copy of the consent form if they would like one, and the notetaker documented in the interview notes whether the participant chose to receive a followup email with the consent form. The consent to record was also documented in the interview notes. Video recordings were destroyed immediately following the completion of the interviews, however, any notes, audio recordings, and transcripts used by the NORC study team to develop the final report will be destroyed following the conclusion of the Committee’s work on June 30, 2023.

Data Analysis

Each interview was automatically transcribed by the Zoom platform and reviewed for accuracy by NORC project staff. Analysis of early interview transcripts was done using a modified grounded theory approach,5 where emerging themes were used to build explanatory models of relationships between items. When possible, the team implemented “in vivo” coding, which used respondent’s own words and phrases as themes, such as grantees use of CARA grant funds to “enhance partnerships” with

community organizations. This enabled the team to generate probes iteratively from interview to interview and to incorporate respondent feedback on topics.

Throughout the data collection period, the NORC team met often to discuss emerging findings and kept a running list of themes, which was expanded as new topics emerged until saturation occurred. After all the interviews concluded, the team performed deductive coding and analysis on the entirety of interview findings, using the preliminary themes that had been identified previously as well as any new themes that emerged. A flat coding structure was used to assign equal relevance to all themes. Each team member in charge of the analysis was assigned a subset of interviews to review to ensure the comprehensiveness of themes and perform coding verification. After coding and analysis were complete, overlapping thematic topics were consolidated and organized by the five topic areas shown in Exhibit 4.

Limitations of the Research

This study provides a snapshot of the experiences of grantees implementing and evaluating their SAMHSA-funded CARA grants. Study limitations include:

- Although the sample of 22 grantees enabled us to capture rich, qualitative data with some diversity along program, urbanicity, region/operation, grant award year, and organization type, the generalizability of findings is limited—a constraint with all qualitative research.

- Self-reported interview data can suffer from issues such as recall error. Additionally, grantees were told during the outreach process that they did not need to prepare anything before the discussion, however, if they felt that they might want to refresh their memory about a few program details, they were welcome to do so. That said, there was no requirement for grantees to bring copies of their original proposals, work plans, evaluation plans, progress reports, or final report to the interview or review them prior. Whenever possible, interviewers made attempts to “validate” interviewee perceptions via probes.

- Subgroup analyses that stratified findings by program, urbanicity, region/operation, grant award year, organization type, interview type (individual vs. small group), and interviewees’ roles within their organization were not always feasible, given the risk posed to the confidentiality of participants. Therefore, experiences of grantees in subgroups may vary.

- A total of 23 grantees did not respond to our request for an interview. Therefore, findings may suffer from some degree of nonresponse bias. That is, the experiences of those who did not respond may be different than those who were interviewed and whose responses were included in this study. However, nonresponse was not found to be systematically associated with grantee characteristics.

Findings

Participant Background

On average, two individuals were present for each interview, with a total of 38 individuals participating across the 22 interviews conducted. While most interview participants served in grant leadership roles, such as project director (PD) and PI/co-PI, in some cases evaluators and program managers also participated, enabling inclusion of varying perspectives. Within their respective organizations, interview participants were likely to hold senior management titles, such as executive director or chief executive officer. Some participants had administrative titles, such as prevention specialist, lead evaluator, or grants managers, and were involved in program implementation or evaluation and monitoring. Interviewees had varying tenures at their respective organizations, ranging from two to 33 years.

The majority of interviewees maintained their role on the grant throughout the entirety of the grant period. Individuals whose roles changed reported transitioning from a role with more active day-to-day involvement in the project to one that required more project oversight and management, i.e., from training facilitator to PD or from evaluator to PD. About half of the participants had either developed or written the CARA grant proposal. Regardless of title, tenure, or involvement in the proposal, all interview participants were knowledgeable about their grant program and able to speak to the broad set of discussion topics identified in the initial outreach email (see Appendix A) and included in the interview guide (see Appendix C). No interview went beyond 1.25 hours.

Grant Program Goals

In general, grantees’ descriptions of their CARA program goals were consistent with the required grant activities. Exhibit 5 shows the goals associated with each of the four programs. As shown, most programs had identified goals geared toward the establishing partnerships or connections with community-based services or networks. Other common goals included conducting trainings with program implementers, key community members, or providers and pharmacists related to carrying, administering, or prescribing overdose prevention medication. The two CSAP programs (FR-CARA and OD Tx) had a goal to establish processes or create protocols for referring overdose survivors to treatment. The two CSAT programs (PPW-PLT and BCOR) had goals to increase availability or support the development, expansion, or enhancement of recovery support services.

Some grantees were able to identify the original targets they had set for each goal, for example, the total number of individuals trained, or the total number of overdose prevention medications distributed. Other grantees noted they were unable to remember the original targets identified in their proposals and/or outcomes documented in their final reports. As noted previously in the study limitations, grantees were not asked to have copies of their original proposals or final reports available for these interviews or to prepare in advance of the interviews.

Exhibit 5: SAMHSA-funded CARA Grant Program Goals

| CARA Grant Program | Associated Goals |

|---|---|

| PPW-PLT |

|

| BCOR |

|

| FR-CARA |

|

| OD Tx |

|

Establishment of Partnerships. Grantees were asked about the types of partnerships they established to achieve program goals. Often, they described strengthening and building partnerships that would change attitudes toward persons in recovery as well as increase access to services. This included establishing partnerships with health departments, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), and medical centers. Most grantees across the CSAP and CSAT programs described having either formal partnerships with local entities (e.g., law enforcement agencies or fire departments) or informal collaborative relationships with community organizations (e.g., local shelters; see quote from ID 1104). For further discussion on the impact the SAMHSA-funded CARA grants had on grantees’ ability to create new partnerships and sustain existing ones, see the Grant Implementation Process section.

“I would say it really helped us increase our partnerships with law enforcement, public safety, first responders, treatment providers, and community coalitions. While we had a rapport previously … we’re frequently coming together with our advisory council, they’re giving us suggestions and so I feel like we are better situated now because of our close work ties that we’ve had through the grant . . . so I would also add better partnerships.” – ID 1104 (CSAP)

Related Activities in Place Before Receipt of CARA Funding. Only one CSAT grantee’s organization reported not being actively engaged in activities related to those proposed in the CARA grant prior to award. Most grantees reported being engaged in related activities before receiving SAMHSA funding, such as the following:

- Grantees across the CSAP and CSAT programs noted that the CARA grant enabled them to expand on pilot programs or other work underway, including expanding target populations or geographic service areas and consequently increasing the number of eligible clients.

- Several CSAP grantees noted that the CARA grant allowed them to expand training to new populations, including first responders, law enforcement agencies, and health system employees.

- One CSAP grantee noted that the grant expanded both training capacity and availability of overdose prevention medication (see quote from ID 1007).

“Also, we’ve been able to do a lot more work in terms of expanding and increasing the amount of naloxone overdose education and distribution . . . The grant funding has been fantastic for that . . . So, before we would get a lot of requests to do trainings, which we did as best we could, go to a program and we train their staff on how to use naloxone and respond. But it was sort of like a one and done, and a lot of them actually kept coming back to us months later, and say ‘we have new staff can you do this again?’ And now we’re able to offer this training, but then also help them become their own program and have capacity to distribute naloxone. So, then it’s not just a one and done.” – ID 1007 (CSAP)

When asked about the impact they were hoping the SAMHSA funding would have on these related activities, grantees reiterated their primary objectives of expansion of and/or increased access to services already being provided, enabling them to reach more people. At the same time, grantees elaborated on the broader impact their CARA grant program could have on individual attitudes and public perception on overdose and recovery by highlighting the need within their community. For example, two CSAT organizations described wanting to use the grant to demonstrate the need for more community-based services or alternative forms of treatment and services that did not include incarceration.

Grant Implementation Process

Implementation Successes. Grantees were asked to identify key successes achieved while implementing their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program and the factors that may have contributed to those outcomes. One of the most noted successes was the establishment of new partnerships and/or strengthening existing partnerships.

- Several grantees across the CSAP and CSAT programs noted that because their organizations were already well established in the community and/or they were part of a strong network, they were able to get their program up and running quickly, collect and share information and data efficiently, and ultimately serve more clients.

- For grantees less established in their communities, they perceived that their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program conferred more credibility when trying to create new partnerships with key stakeholders and larger well-known organizations (see quote from ID 1033).

- BCOR and FR-CARA program grantees identified partnerships as a success more often than the remaining two programs, which is consistent with their grant program goals.

“People don’t really want to partner, ‘oh, that’s just the recovery house,’ or ‘the meetings at that place are just for recovery individuals.’ The stigma is still there. That was a big barrier, just trying to get my foot in the door with larger companies . . .for me to just step in, and boom, I get a grant from SAMHSA, they’re like, ‘where did she come from.’ It takes work, we are continuously working at it. Many years ago we did the parade, well, now we’re invited to the parade all over. . . going to events, showing up at board meetings. We may not be wanted but guess what, we show up. We are at every single event, whether it’s a community event, if it’s a recovery event, if it’s a high school . . . there’s always a brick wall, and I’d either climb over it, or we bust through it . . . just keep pushing.” – ID 1033 (CSAT)

The second most commonly reported success was the impact organizations had on reducing stigma in their communities. Grantees often attributed reduced stigma to both an increase in overdoses and the grant requirements—specifically educating individuals through trainings and events, including parades, conference presentations, annual staff retreats, and other recovery-focused activities. For example, one CSAP grantee described the shift in perspective among first responders as they learned who was experiencing overdoses (see quote from ID 1017). Relative to the other two programs, BCOR and FR-CARA program grantees more often identified the reduction of stigma as a success, perhaps because it was an explicit program goal.

“You know 5-10 years ago people weren’t really talking about [overdose] the way they’re talking about it now . . . it was taboo, back alley, you know a lot of judgment and a lot of stigma. Unfortunately, there is still a lot of stigma but . . . what was happening is a lot of our [first responders] are natives, they grew up here, these are their neighborhoods they’re servicing and they would be responding to overdoses at homes of people they knew and suddenly it wasn’t a distant disease anymore, it was ‘oh, I played basketball with him growing up,’ or ‘my kid plays soccer with her kid,’ and all these connections were being made. And now that . . . it’s real to them they care more. So they start calling [us] and they’d be like, ‘hey, can you help us get a bed for this person, it’s a family friend,’ or ‘it’s a friend of a friend,’ or ‘this kid just graduated,’ like these personal connections are coming out and now they want to be carrying narcan because . . . everyone has been affected by [overdose] in some way, shape, or form and so that buy in and that want to help the community really helps, like they are invested in helping this community.”– ID 1017 (CSAP)

CSAP programs often cited as a success meeting and/or exceeding CARA grant program requirements and initial targets grantees had set for themselves. In contrast, this was not mentioned by CSAT grantees. Several grantees highlighted their ability to train large numbers of first responders, especially law enforcement officials and other key community members. A few grantees highlighted their ability to successfully collect follow-up data on individuals trained, individuals who received overdose prevention medication, and/or individuals who experienced an overdose.

Some PPW-PLT and FR-CARA program grantees noted successfully extending the use of their funds beyond what they had originally proposed with approval from their SAMHSA program/project officer (PO). They noted that this increased capacity to serve more clients. Some examples of these efforts include:

- One FR-CARA grantee requested to expand the use of funds to include first responders at different agencies within the same geographical location.

- Another FR-CARA grantee received approval to expand the use of funds to serve clients struggling with substances beyond opioids.

- A few grantees requested and received approval to expand the use of funds to support mobile response efforts, particularly in rural areas.

Implementation Challenges. Several CSAT grantees and one CSAP grantee identified delayed funding from SAMHSA as adversely impacting their program start-up. Additionally, while the establishment of partnerships was identified as a success, several grantees across the CSAP and CSAT programs also identified this as an area where they experienced challenges leading to slow program start-up. This was particularly relevant among grantees trying to partner with emergency departments (EDs) or FQHCs. Grantees noted that staff and physicians at these locations have limited availability and often would not engage in trainings unless there was a tangible benefit to them, for instance, through continuing medical education credits (CMEs; see quote from ID 1011). In some instances, potential partnering organizations were simply unaware of the impact of opioid overdose in their communities and ultimately how to prevent and/or treat it. This delayed the establishment of partnerships with grantees, and in turn, the implementation of the grant program.

“Clinical staff at hospitals, their time is so limited and the trainings . . . they had to have something they were getting from it, like CMEs, otherwise they weren’t available to kind of block off that amount of time. But I think we all can understand that EDs are busy places, and so it was just difficult sometimes just getting in the door in a way to that would allow us to even have that conversation. I think those are the challenges that existed before COVID and then, of course, when COVID happened, the focus of what hospitals were trying to do shifted. While their broad intention of saving lives includes overdose, it actually became a literal challenge getting into the hospitals. . . but I think that’s really the challenge that has existed throughout this program is hospital emergency department collaboration and detailing.” – ID 1011 (CSAP)

With the exception of a few FR-CARA grantees that successfully collected follow-up data from clients, most grantees across the CSAP and CSAT programs identified the follow-up requirement of the SAMHSA-funded CARA grants as a major challenge. Some grantees acknowledged underestimating how difficult it would be to reach individuals who had experienced an overdose, even with information such as the location/address where the overdose occurred and phone number. In some instances, this difficulty was only heightened due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions on in-person contact. Although grantees had implemented creative ways to collect follow-up data on individuals who either received overdose prevention medication or used it (e.g., via post-cards, QR codes, brightly colored stickers with links to websites, text messages), it often did not suffice from a required reporting standpoint. Lastly, a few grantees noted it was difficult to collect 30-day follow-up survey data from individuals who had attended a training and/or event.

While several grantees were successful at reducing stigma within their communities, it remained a challenge for other grantees across the CSAP and CSAT programs. Grantees identified stigma among individuals administering overdose prevention medications (e.g., first

responders, key community members) and individuals at risk of experiencing an overdose. Individuals responsible for administering overdose prevention medication would refuse medications after trainings or be reluctant to partner with grantees due to stigma. Grantees noted that for those at risk of experiencing an overdose, they were less likely to receive overdose preHeavention medication kits if being asked to complete documentation of any kind—for example, asked for a name or demographics. Grantee solutions or strategies that were reported included:

- To comply with CARA grant required activities, one CSAP grantee created an online form, accessible at the click of a button, for clients to complete once they received an overdose prevention medication kit. After completing the form, the medication would automatically be added to the client’s list of current medications accessible to clinical and medical staff. Even though this approach was adopted to ensure the client safety, the grantee noted that clients were still less likely to take overdose prevention medication kits for fear they would have a permanent mark on their record identifying them as someone at risk of overdose.

- Another CSAT grantee noted that many individuals and organizations within their community believed 12-step approaches were the only path to recovery, which requires individuals to remain abstinent from substances of any kind, including medications used to treat substance use disorders. Therefore, the first six months of their grant was focused on educating community members about the many pathways to recovery, including harm reduction.

A few CSAP grantees noted the creation of a data dashboard or repository to facilitate data sharing as a success of their CARA grant. However, several CSAP grantees also noted limited staff time and access to data as a challenge. For some, this was due to underestimating the amount of support they would need to implement their SAMSHA-funded CARA grant program. Additionally, treatment organizations external to CARA grant programs were not always willing to share data due to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy concerns, while other partnering organizations found it difficult to share data elements beyond those available in their EHR system.

Many CSAT grantees identified a lack of nonclinical resources and support services for their clients (to address non-medical social needs) as a challenge, such as housing and transportation not only for individuals who had experienced an overdose but also their families, including spouses, children (over 12 months of age), and caregivers. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, barriers to communication beyond in-person became apparent, including internet access and the cost of cell phone data. This was especially challenging for grantees trying to expand access to support services in rural areas to facilitate recovery. Grantees also noted that there is a clear need for more support and resources to secure medications for clients to treat opioid use disorder, especially in states where Medicaid was not expanded. While some of these grantees tried reaching out to their SAMHSA PO to overcome these challenges (for example, to receive approval for expanding the use of funds), they were not successful due to reasons such as no PO was assigned or no response was received from the PO (for further discussion on grantees’ experiences with SAMHSA, including their PO, see the Recommendations for Future Policy and Program section).

Grantees reported implementing a number of successful approaches to overcome the challenges identified. As noted previously, several grantees successfully worked with their POs to expand the use of CARA grant funds. However, others reported that hiring the right staff, including those with lived experience and recovery champions within the community, was critical to achieving their goals. Hiring professional staff that were able to provide consistent communication with both internal staff and external partners was also identified as a key solution strategy. For a few other grantees, it was just about “digging in,” moving forward, and getting the work done (see quote from ID 1021).

“We just dug in and got it done. I mean really, that’s all you can do is just dig in and get it done.”– ID 1021 (CSAP)

Perceptions of the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. A few grantees noted that the COVID-19 pandemic had no impact on their program or service delivery, due to specific organizational-level characteristics (for example, the organization usually operated 24/7, responded to emergency situations, and functions mostly online). Others, however, identified impacts on both their community and organization. Within the community, several grantees noted seeing increased rates of overdoses, while within their organizations, grantees noted COVID had “put a wrench in any forward movement” (ID 1027, CSAP) and dramatically slowed internal operations due to staff fatigue and burnout (see quote from ID 1016).

“You know my first responders, my recovery coaches, everyone was feeling the burden and the fear because everything got so much more complex. . . The amount of overdoses, the amount of burnout and fatigue and secondary trauma spiked. The capicity vs. demand was completely off. . . . I can say we responded as best we could, as much as we could, and people seem to think we did a pretty good job.”–ID 1016 (CSAP)

A few grantees highlighted the initial struggle that came with the COVID-19 pandemic, including the need for “social distancing” requiring a transition from in-person to virtual care (see quote from ID 1031). Virtual care seemed inconsistent with the needs of individuals in recovery, as one grantee described, “addiction happens in isolation, recovery happens in community” (ID 1037, CSAT). However, grantees acknowledged that they started to see the benefits of this transition, specifically via decreased costs or savings associated with in-person trainings because of meeting spaces, travel expenses, and travel time and expansion in the number of individuals who could attend virtual trainings and receive services.

Grant Evaluation Process

Grantee evaluation efforts focused mostly on SAMHSA requirements, specifically the web-based reporting tools—GRPA and DSP-MRT. While most grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs identified other types of information that they collected outside of required reporting (e.g., client demographics,

“COVID-19 was a major challenge. We had a drop in face-to-face contact, and then, you know, some of the terminology that we use, I mean it was for good intentions but it kind of, you know, social distancing. . . when we want people to socially connect we are telling them to social distance. It didn’t align with recovery. . . social distancing is physical distancing but the way we are talking about that is like, ‘I don’t want to see you,’ things like that. COVID-19 was a really, really, I mean, it is still a really big problem.” – ID 1031 (CAST)

satisfaction surveys, county data on ED visits, client assessments, fatal and nonfatal overdoses), they noted that they often did not have the time, staff, or resources to analyze data beyond what SAMHSA required. This limited their ability to quantify impacts on subpopulations, their organizations, or the community. One CSAT grantee described overcoming the challenge of collecting GPRA data using incentives with clients and staff training to achieve targets (see quote from ID 1039).

Contracting with an external evaluator to assess program success was more prevalent among CSAT than CSAP grantees. Specifically, all but one CSAT grantee contracted with an external evaluator, while only five CSAP grantees did so. Most grantees that contracted with an external evaluator described having a good experience, but a few noted that the evaluators were expensive, and they would have preferred to use that money elsewhere. Only a few grantees reported a negative experience working with their evaluator, ultimately leading to termination of the evaluator’s contracts and in at least one instance losing data.

S1: “So that’s probably no surprise to you, but yeah GPRA’s our challenge, just because of the kind of questionnaire they are, on the way that they’re asked to be delivered, and followed-up on with this population can be difficult… We had to incentivize [follow-up surveys] for a while and that was really helpful, so we had written some funds to provide like small gift cards. Before the completion of follow-up surveys and that was, I think, pretty effective. We also, did a really good job, [staff] did an amazing job, of training our team on how to really go after those and be accountable to our GPRA numbers because it was a deliverable from the grant.”

S2: “I think engaging people and then like building that rapport and then just being really accepting when we just couldn’t access somebody whether they were back in treatment or in some type of facility.” – ID 1039 (CSAT)

Experiences with Web-Based Reporting. Grantees were asked whether they felt the SAMHSA required web-based reporting tools (GPRA and DSP-MRT) adequately captured the success, achievements, and activities of their CARA grant program. One CSAT grantee had a very positive reaction to the web-reporting tools and felt the information collected told “a good story about what was going on with each [client]” (ID 1031, CSAT). A few other grantees felt the web-based reporting tools were “ok,” “nice,” or “pretty user-friendly,” and “did a decent job capturing information.” However, several grantees, mostly from CSAT programs, shared their frustrations and dislikes with the required reporting tools, including the following:

- Grantees did not feel like these web-based reporting tools captured the full story of their program, especially in the first year or two of the grants (see quote from ID 1034).

- Additionally, grantees felt these tools focused on quantity over quality, were concerned mostly with where the money flowed, and created a lot of administrative burden.

“I just think that tool in general, I get the purpose, I understand why, but no, it is not adequate in capturing what’s really going on with these programs. . . I don’t think that it’s a low barrier tool and it’s just too long. It is supposed to be conducted right at the beginning, when you don’t have trust, there’s not alot of time to build trust and familiarity, you’re asking really personal questions right out of the gate. Then there’s the followup piece that again was starting up, you know, the likelihood of finding someone after six months is low. So yeah, I thought, all those were pretty big barriers.” – ID 1034 (CSAT)

- One CSAP grantee noted that although their CARA grant did not have a followup requirement, they had worked on other SAMHSA grants that did and felt it was non-conducive to facilitating services and leading grantees to cherry pick clients that are more likely to follow up rather than serving those that need the greatest level of care (see quote from ID 1010).

- A few grantees noted that there was a mismatch between the web-based reporting tools and the required intentions or activities of the grant (see quote from ID 1037).

“When GPRA has individual level follow up at intervals it’s super non-conducive to facilitating services. It’s super cumbersome, super burdensome, and makes it, because [SAMHSA] wants a 80 percent follow-up rate, and that makes it so that you’re not really going to serve the people that need the help. It’s going to make it so you cherry pick the people that you think are going to have follow up with you at certain intervals. The whole GPRA system as whole needs to be reworked in order to facilitate equitable access to services.” – ID 1010 (CSAP)

“What we are required to put into the SPARS system is a survey that’s administered at the end of an event and 30-days post and it actually does not line up very well with the required intentions of the grant. So that’s always interesting because your administering a measure which does not feel valid when it comes back to the objectives. Like, it’s not the thing that would tell you those items were achieved, and because these were retrofitted from the ATTC grants, the training and technical assistnace grants, they were geared towards professional development so a lot of the folks participating in [various events] where answering a series of questions that were somewhat non-applicable and kind of confusing, and our [SAMHSA] PO acknowledged that this doesn’t necessarily line up.” – ID 1037 (CSAT)

A few grantees suggested how SAMHSA could improve the web-based reporting tools, specifically, by requesting data or providing fields for data that most jurisdictions collect or have access to (e.g., syndrome and surveillance data, and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) data including non-fatal overdoses), not limiting the number of characters for specific responses, and “allow for different ways to tell the story,” beyond numbers, for example, via the inclusion of bar graphs (ID 1008, CSAP). Reducing administrative burden was identified by several grantees as important for their programs to have a greater impact, particularly as it relates to web-reporting requirements through both electronic research administration commons and SAMHSA’s Performance Accountability and Reporting System (SPARS). By reducing administrative burden, grantees noted that they would have more time to spend on implementing the grant and providing direct services to clients.

Grant Program Impacts and Sustainability

Grantees were asked to discuss the perceived impacts of their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs and their plans for program sustainability. In general, all grantees believed they were able to achieve at least some of their program goals.

Perceived Impacts of Grant Program. A few grantees were enthusiastic that they had “knocked it out of the park” (ID 1039, CSAT), while others were more reserved in their responses, identifying specific goals they successfully achieved (e.g., distributing naloxone and conducting trainings) and other

requirements they struggled with (e.g., collecting follow-up data). Some examples of key impacts that were identified included:

- Many grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs noted that meeting and/or exceeding the requirements of the SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program and the original targets grantees had set for themselves (see Grant Implementation Process section for more on this).

- Two CSAT grantees shared that while their organization struggled to meet their original targets, leaving them feeling “like a failure,” (ID 1034, CSAT) but added that the work they were able to achieve was of high quality (see quote from ID 1003).

- Another CSAT grantee shared that they later learned that they could revise their target numbers accounting for some of the challenges and barriers they faced, which helped to improve the program team’s morale.

- Several CSAP grantees noted that “this [grant] has saved hundreds if not thousands of lives” (ID 1026, CSAP) and substantiated this claim by providing a brief story of a specific individual (see quote from ID 1008) or highlighting the number of successfully administered overdose reversal drugs or the number of nonfatal overdoses that had occurred in their community.

“Yeah, numbers are low, but our quality was awesome, and I couldn’t quite get the right people [at SAMHSA] to listen to that. . . This was amazing to me because our treatment population is primarily Caucasian, we had the best retention rate out of Black women and Black fathers and . . . I kept trying to say that all the time. . . and nobody was listening.” – ID 1003 (CSAT)

“I could tell a story about a young man that had been experiencing overdose after overdose. By going out and reaching him through the connection with [first responders], he’s doing well. You know he still has his setbacks, it’s all part of recovery, but he is doing really well and it was part of us getting in there with the Narcan. We went to a drug-using house, knocked on the door, handed them the Narcan and our business cards and said call us, and he called us.”– ID 1008 (CSAP)

Efforts Related to Program Sustainability. All grantees noted that they wanted to continue, in some capacity, the activities they had implemented under their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program. However, plans for how to sustain the work done under the CARA grants varied. Some grantees noted that they had not yet used the SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program or corresponding financial or impact assessments to leverage additional supports. Others reported that they were actively applying for or had already received additional federal, state, and/or local funding, including new SAMHSA CARA grant funds. For example,

- One CSAT grantee reported leveraging their existing SAMSHA-funded CARA grant to obtain additional SAMHSA funding that they believe they otherwise would not have received.

- Several other grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs noted that they were able to leverage the data collected under their CARA grant to obtain additional funding. For example, they shared that through their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant, they were able to demonstrate a

- community need as well as their organization’s impact, which then enabled them to secure other funding, including additional SAMHSA CARA grant funds (see quote from ID 1017).

“So we are budgeted to have [specific overdose support] three days a week, we really can’t afford to be doing more than that, just within our budget criteria and [City Hall] were like we will pick up the extra two days of the week…so it has encouraged them to like be more focused on it. Two years ago, [City Hall] would have been like no, we’re not giving you more money and now they’re like invested into helping.” – ID 1017 (CSAP)

Several grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs noted they felt confident they would be able to acquire the funding necessary to maintain the internal supports (e.g., staff) and processes (e.g., trainings) that were established under their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program, however, identifying additional funds to cover the cost of overdose prevention medications was seen as a bigger hurdle for CSAP grantees. Some grantees are considering changes to their organization and workflow to be more sustainable in the absence of CARA grant funds. For example, one grantee is considering shifting more of their outreach and tracking to an automated system to reduce the number of staff needed. Another CSAP grantee is exploring alternatives to Narcan that may be more financially sustainable (See quote from ID 1008).

“I’m more concerned about funding for the Narcan as it gets very expensive. We have also recently looked at a different brand. It actually gives a higher dosage of the medication where Narcan is four milligrams and the alternative is an eight milligram for the same price. So we’ve been exploring that as an alternative, because then maybe you don’t have to give somebody two doses, you can give somebody one dose and it’s the same cost.” – ID 1008 (CSAP)

Recommendations for Future Policy and Programming

Grantees were asked to provide suggestions for what SAMHSA might have done differently to maximize the impact of CARA grant funding. In addition, they were asked to provide recommendations to increase the impact of future funding provided by the federal government to address opioid misuse, overdose, and other substance misuse.

Grant Management-Related Recommendations. Grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs wanted SAMHSA to be more intentional in interactions with them while also being more present, including consistent communication between grantees and SAMHSA POs. Almost half of grantees interviewed had either a strained or nonexistent relationship with their SAMHSA PO due to a lack of communication and/or having a new PO assigned up to three times during their grant.

Several grantees mentioned wanting SAMHSA to facilitate more collaboration among grantees, so that grantees can learn from one another and exchange ideas for overcoming challenges. They suggested that SAMHSA could factor in grantee collaboration into future funding opportunities and make a conscious effort to initiate and foster collaborative processes over the entirety of the grant.

Funding-Related Recommendations. Grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs noted that they would like to see more flexibility within SAMHSA-funded grant requirements to adapt to the changing environment, especially considering the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the unique

needs of different states, jurisdictions, and/or municipalities. Some specific recommendations made in this regard included:

- Grantees suggested that funding be expanded to include other substances, including more potent and/or synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, and substances beyond opioids, including methamphetamines and alcohol. They noted that the state of the opioid epidemic had shifted since the SAMHSA-funded CARA grant solicitation was released, from higher rates of heroin and prescription opioid use in 2016 and 2017 to higher rates of fentanyl and combination drug use (methamphetamines and opioids) in 2021 and 2022. Additionally, grantees serving rural populations noted that methamphetamine and alcohol continue to be a problem, with even higher rates of misuse and disorder than opioids (see quote from ID 1003).

- Grantees responded that they would also like to see funding requirements expand to include mental health services in addition to substance use (and for covering medications for prevention and treatment of both), since these conditions often co-occur.

- Grantees also mentioned wanting to use funds beyond specific counties or entities (e.g., first responders) to include other organizations like local health departments and schools. As noted in the Grant Implementation Process section previously, some grantees successfully expanded the use of CARA grant funds to include additional services like mobile prevention or expanded to other geographic locations like surrounding counties.

“Well, honestly, I think we are addressing the opioid epidemic pretty well. We still have a meth epidemic in our rural areas, where I feel like we are losing funds in that capacity. We have robust created a whole medication supportive recovery system, we’ve expanded services, and all that. And not that the opioid crisis has gone away, but we never took care of the first one.” – ID 1003 (CSAT)

A few BCOR grantees mentioned that they would like the requirement for matching funds dropped. Although matching funds were not required by all SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs, among those that did have this requirement (BCOR grant programs), a few grantees stressed the difficulty in securing nonfederal funds in addition to all the other grant requirements and in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. One grantee felt this requirement has exacerbated the stigma already present among recovery organizations (see quote from ID 1037).

Grantees across CSAP and CSAT programs suggested several areas of focus for future federal funding, including:

- Outreach services.

- Harm reduction services.

- Nonclinical recovery support services, specifically:

- Housing.

- Transportation.

S1: “I beleive it is an inherent bias toward recovery organizations.”

S2: “I know this is new, funding recovery and recovery community organizations, and I think that there is still so much stigma even at the federal level that this money is there, this is how I describe it, we’ve been invited to the dance, but we still have to stand against the wall. We’re going to let you come in and make you feel included but we’re just not sure what you’re going to do with the money.” – ID 1037 (CSAT)

-

- Social services.

- Basic needs, especially for recovery community organizations (e.g., clothing, food, building maintenance).

- Medications (e.g., low-threshold buprenorphine or injectable buprenorphine).

- Care coverage and supports for the client’s family and caregivers.

Finally, grantees noted they would like to see funding for longer implementation periods. As one CSAT grantee noted “recovery is a lifetime, I know you can’t fund them a lifetime, but you know more than three years would be beneficial” (ID 1036, CSAT). They also noted the importance of receiving reimbursement for the two largest operating expenses, staff and supplies, including overdose prevention medication. Grantees also noted that funders should support more intentional integration between behavioral health and physical health care to encourage participation by EDs and other health care providers.

Conclusion

NORC conducted qualitative research to understand the factors that impeded and/or facilitated grantees’ implementation and evaluation of their SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs. The goal of this work was to support NASEM and the Committee’s efforts in making recommendations to Congress about the future of the federal government’s response to the opioid crisis. For this study, NORC conducted semi-structured interviews with 22 grantee organizations that participated in the implementation and/or evaluation of one of the four SAMHSA-funded CARA grant programs awarded in FY2017 or FY2018.

This study is an important step toward understanding barriers and facilitators to implementing and evaluating grant programs funded by SAMHSA to address opioid misuse, overdose, and other substance misuse. However, as indicated previously in the Limitations section, this study was unable to capture the full range of barriers and facilitators grantees faced, since it focuses only on the experiences of specific individuals from a subset of grantees. Future research should strive to incorporate the full spectrum of grantees and individuals involved in carrying out the goals of government-funded programs to ensure the inclusion of perspectives at varying levels of the implementation and evaluation process. Additionally, future research should consider conducting in-depth interviews at various stages across the implementation cycle to minimize recall error and capture early program challenges and successes following start-up as well as when the program reaches a “steady state.”

Despite these limitations, this study identified a range of factors that either impeded or facilitated grantees’ implementation and/or evaluation of their CARA grant program. For example, establishing new partnerships and/or strengthening existing partnerships was one of the most noted successes as well as challenges. Who grantees chose to partner with and the quality of those partnerships predicted how quickly grantees were able to get their programs up and running, how efficiently they were able to collect and share information, and ultimately how many clients they were able to serve. However, it was

challenging for less-established programs to put partnerships in place that could support timely, effective implementation.

In addition, stigma—a long-term barrier to substance use disorder treatment and recovery—played a significant role in both the successes and challenges identified by grantees. While several grantees were successful at reducing stigma in their communities through education and trainings, it remained a challenge for others. In one instance, stigma interfered with a grantee’s effort to overcome the challenge of collecting follow-up data from individuals who received and/or used overdose prevention medication. However, it is important to note that in several instances securing SAMHSA funding gave grantees the credibility, clout, and confidence to persist in the face of entrenched stigma. The CARA grant program requirements supported grantees in making considerable inroads in their communities to change attitudes and perceptions about individuals experiencing overdose and/or in recovery.

Importantly, respondents reported a mismatch between grant requirements and the realities experienced by this population and the organizations serving them. Grantees identified several limitations regarding how funds could be used, what data must be collected, and how it is reported. Additionally, as one grantee noted “recovery is a lifetime,” therefore, funding needs to be more conducive to this reality and the many pathways to recovery, including harm reduction.

Finally, respondents had mixed reactions to the support—or lack thereof—from SAMHSA, more specifically their assigned POs. For grantees with prior experience implementing and/or evaluating SAMHSA-funded grants, having regular communication and check-ins with their PO was not always needed. However, for grantees with little to no experience implementing and/or evaluating SAMHSA-funded grants, access to their PO was critical to ensuring accurate interpretation and execution of the grant requirements. Additionally, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ever-evolving landscape of opioid misuse and other substance use, grantees required additional support and guidance to expand the use of their funds in unique and creative ways to ensure those at greatest risk of experiencing overdose were being served. Unfortunately, though, that support and guidance was not always available, leading to outcomes that may not have looked impressive on paper but were pivotal to the lives of those receiving services. Despite the challenges grantees faced, their determination for making a difference and commitment to their clients was evident in their reported outcomes, including number of trainings conducted, number of overdose prevention medications distributed, and number of clients referred to treatment.

References

1. Text - S.524 - 114th Congress (2015-2016): Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016. (2016, July 22). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524/text.

2. Text - H.R.1625 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018. (2018, March 23). https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1625/text

3. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2020). Measuring Success in Substance Use Grant Programs: Outcomes and Metrics for Improvement. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25745.

4. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021). Progress of Four Programs from the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26060.

5. Bernard, H. Russell, Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. (London; Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2000), pp. 443-444.

Appendix A: Outreach Emails

Initial Outreach Email

Subject Line: Request to Participate in a Study Related to SAMHSA-funded CARA Grant Programs

Hello [PI/Co-PI Name],

We hope this email finds you well.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the ‘National Academies’) is conducting a consensus study to understand the progress made on Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-funded Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) grant programs to reduce opioid-related harm and promote recovery from substance use disorders. So far, their research activities have resulted in two reports. For this third and final report, the National Academies has contracted with NORC at the University of Chicago (NORC) to gather qualitative information toward supporting the National Academies’ conclusions and recommendations to SAMHSA about the effectiveness of CARA programs and the future of the federal government’s response to the opioid crisis.

NORC plans to conduct virtual interviews with individuals from approximately 45 grantees under the CARA program. We are reaching out to you today because we are hoping that your organization/agency, as one such CARA program grantee, would be willing to participate in this NORC study. You should have recently received an email from Kathleen Stratton at the National Academies letting you know that we would be contacting you. Please note that the NORC study does not seek to duplicate the information that your organization/agency may have previously provided to SAMHSA. Rather, we are interested in hearing about your organization/agency’s insights and experiences with implementing and evaluating your CARA grant program, that can supplement any prior reporting to SAMHSA on the progress of your CARA grant program. Your participation will help to ensure that the National Academies’ recommendations to Congress are responsive to the experiences of CARA grantees.

Participation in this study will comprise a 45–60-minute virtual discussion that will occur between April and May with an interviewer from NORC. If your organization/agency is willing to participate in this study, then we are also hoping that as the PI of your CARA grant program, you will be able to help identify the most appropriate individual for the discussion (that is, whether it should be you or someone else). For the discussion, we are specifically looking for someone who has been involved in both the implementation and evaluation of your SAMHSA-funded CARA grant program, and therefore would be able to speak to a broad set of discussion topics including the following. You do not need to prepare anything prior to the discussion.

- Program goals and activities,

- Successes and challenges related to program implementation,

- Progress on program evaluation (with a specific focus on data collection), and

- Program sustainability and recommendations to the federal government for future funding of similar programs.

[IF FR-CARA/BCOR USE THIS SENTENCE] We want to reassure you that your organization/agency’s participation in the study will not be made known to SAMHSA or the National Academies, and no staff outside of the NORC Study Team will know your identity or be involved in the discussion itself.

[IF OD Tx/PPW-PLT USE THIS SENTENCE] We want to reassure you that no staff outside of the NORC Study

Team will know your identity or be involved in the discussion itself.

All interview responses will be kept confidential and stored separately from contact information, and all such data will be stored on a highly secure and encrypted server at NORC. NORC will not share contact information or interview responses with anyone outside our Study Team. Furthermore, all our reported findings to the National Academies will only represent aggregate opinions across interviewees so that none of the findings will be attributed to individuals, and re-identification of individual respondents would not be possible by either the National Academies or SAMHSA. Finally, neither the National Academies nor SAMHSA will have access to audio or video interview recordings. Video recordings (if applicable) will be destroyed immediately, and audio interview recordings and transcripts will be destroyed by June 30, 2023. Neither NORC nor any other entity will be able to re-use data collected under this project for another research study.

Additional information on this study is provided in the attached Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) document.

Please reply to this email by <insert date> to let us know if your organization/agency would be willing to participate in this NORC study. Please also let us know whether you would be the most appropriate interviewee and if not, kindly provide the names and email addresses of alternative participants. The NORC study team can accommodate up to three participants on an interview. Once identified, the NORC study team will contact the appropriate interview participant (whether you or someone else) within a few days of receiving your response to this email to schedule the virtual interview.

Thank you for helping support this important work. We look forward to hearing from you!

Best,

The NORC Study Team

Follow-Up Interview Email for PI/co-PI as Respondent

Subject Line: Invitation to Participate in a Confidential Discussion for a Study Related to SAMHSA-funded CARA Grant Programs

Hello [PI/Co-PI Name],

Thank you very much for your willingness to participate in a confidential virtual discussion with an interviewer from NORC at the University of Chicago (NORC), about the process of implementing and evaluating your Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)-funded Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) grant program. As was noted in our initial outreach, the findings of our NORC study will help to support the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the ‘National Academies’) conclusions and recommendations to SAMHSA about the effectiveness of CARA programs and the future of the federal government’s response to the opioid crisis.

[IF FR-CARA/BCOR USE THIS SENTENCE] We want to reassure you that your organization/agency’s participation in the study will not be made known to SAMHSA or the National Academies, and no staff outside of the NORC Study Team will know your identity or be involved in the discussion itself.

[IF OD Tx/PPW-PLT USE THIS SENTENCE] We want to reassure you that no staff outside of the NORC Study Team will know your identity or be involved in the discussion itself.

All interview responses will be kept confidential and stored separately from contact information, and all such