Advancing Progress in Cancer Prevention and Risk Reduction: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: Proceedings of a Workshop

Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

The National Cancer Policy Forum hosted a public workshop on June 27 and 28, 2022, to consider the current state of knowledge regarding risk factors for cancer and strategies for interventions across multiple levels to reduce cancer risk. This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the issues that were discussed at the workshop. Workshop presentations and discussions reviewed the current evidence base, examined best practices and innovative approaches for clinic- and population-based cancer prevention, and discussed strategies to promote effective communication about cancer prevention.

Speaker observations and suggestions to spur progress in cancer prevention efforts are included throughout the proceedings and highlighted below in Boxes 1 and 2. Appendix A includes the workshop Statement of Task, and Appendix B includes the workshop agenda. Speaker presentations and the workshop webcast have been archived online.2

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and this Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of the individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

2 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/06-27-2022/advancing-progress-in-cancer-prevention-and-risk-reduction-a-workshop (accessed May 1, 2023).

This workshop is the second in a series examining policy issues in cancer prevention and cancer screening. The first workshop, which took place in March 2020, focused on advancing the development and implementation of effective, high-quality cancer screening (NASEM, 2021b). Since that workshop, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic

illustrated the fragility of the U.S. public health infrastructure, said Garnet Anderson, senior vice president and director of the Public Health Sciences Division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. But simultaneously, she said, it demonstrated that there can be tremendous progress in addressing public health crises when the resources of research, health care, and public

health enterprises are focused on a clear goal. She called for a similar sense of urgency for cancer prevention.

To frame the concept of cancer prevention, Karen Basen-Engquist, professor of behavioral science and director of the Center for Energy Balance in Cancer Prevention and Survivorship at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, used a plant analogy. In this analogy, she compared a plant in the garden to a person. The soil represents the communities people live within: if the soil has the right nutrients and microbes, the plant can flourish; similarly, communities provide resources to promote the health and well-being of their community members. Plants also need water, which she equated with access to health care services. She likened the air surrounding plants to the informational environment—including public health communication—which she said is critical to cancer prevention efforts.

OVERVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE BASE ON RISK FACTORS FOR CANCER

Several speakers provided background on the various risk factors for cancer, both modifiable and nonmodifiable, including the effects of social determinants of health on cancer risk and health outcomes. Several speakers also discussed research advances in cancer prevention.

Examples of Risk Factors for Cancer

Nearly half of cancers—42 percent—are attributed to modifiable risk factors, said Alpa Patel, senior vice president of population science at the American Cancer Society (Islami et al., 2018). For example, tobacco use still accounts for 19 percent of all cancers and nearly 29 percent of all cancer deaths, although policy changes such as tobacco taxes and smoke-free laws have driven down rates of tobacco use.3 Other modifiable risk factors include factors such as obesity, alcohol consumption, and not receiving the vaccine for the human papillomavirus (HPV).4,5,6 For example, excess body fat is associated with 13 types of cancer and accounts for nearly 8 percent

___________________

3 See https://www.cancer.org/healthy/stay-away-from-tobacco/health-risks-of-tobacco/health-risks-of-smoking-tobacco.html (accessed October 3, 2022).

4 See https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/obesity/index.htm (accessed October 3, 2022).

5 See https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/alcohol/index.htm (accessed October 3, 2022).

6 See www.cancer.org/hpv (accessed October 3, 2022).

of cancer diagnoses.7 Patel said that it has been estimated that excess body fat will surpass tobacco as the leading modifiable risk factor for cancer by 2030 (Ligibel et al., 2014).

There are also nonmodifiable factors that contribute to increased cancer risk, said Mary Beth Terry, professor and chronic disease unit leader, Department of Epidemiology, at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and associate director of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center. She noted that there are hundreds of genes in which pathogenic variants contribute to the development of cancers. These genes are referred to as cancer-associated genes, or cancer genes.8 Terry said it is a false dichotomy to say that cancers either develop spontaneously or are attributable to genetic predisposition—all cancers arise because of a combination of environmental factors and genetic alterations, and genetic alterations can be inherited or acquired throughout life (Bogdanova et al., 2013; Mucci et al., 2016; Qing et al., 2020). She noted that many cancer-associated genes are involved in repairing damaged DNA. These genes are important to study because individuals are exposed daily to various carcinogens—agents that cause cancer, often through breaks or other modifications in DNA. The inability to repair DNA damage is one of the strongest risk factors for cancer (Wu et al., 2022). Terry noted, however, that inheriting mutations in DNA repair genes does not necessarily mean that a person will develop cancer; other environmental factors are also at play.

Both genomic and phenotypic assays could be deployed for population-based cancer risk reduction, said Terry. Polygenic risk scores can be used to stratify populations into different levels of cancer risk9 and thus have the potential to tailor cancer screening strategies (Liu et al., 2021). Assigning risk levels based on underlying genetic susceptibility can be helpful for identifying cancer risk for common environmental exposures (Gallagher et al., 2020). She emphasized that cancer risk-reduction efforts need to begin early in a person’s life, as it is estimated that roughly half of all mutations

___________________

7 See https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/obesity-fact-sheet (accessed April 23, 2023).

8 See https://www.cancerquest.org/cancer-biology/cancer-genes (accessed April 16, 2023).

9 A polygenic risk score is “an assessment of the risk of a specific condition based on the collective influence of many genetic variants. These can include variants associated with genes of known function and variants not known to be associated with genes relevant to the condition.” See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/genetics-dictionary/def/polygenic-risk-score (accessed April 16, 2023).

and epigenetic changes occur before an individual’s body fully matures (Rozhok and DeGregori, 2016).

Philip Castle, director of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Division of Cancer Prevention and senior investigator in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, voiced concerns about relying solely on polygenic risk scores for risk stratification because these models are typically developed and validated using datasets that are not representative of the population. Castle added that stratifying individuals into different levels of risk is not sufficient—these risk levels need to guide clinical decision making and risk mitigation interventions. Terry added that the field leans too heavily on scores for the lifetime risk of developing cancer, but it is often more clinically important to determine a 5-year risk and then evaluate the opportunities for prevention and early detection based on that score. Terry also said that using the word prevention can be misleading when used outside of the population health context: risk can be reduced throughout an individual person’s life, but not all cancers can be averted. Terry said,

If we don’t use the language of cancer prevention but rather use the language of cancer risk reduction—I have learned this from one of my closest community partners that I work with—that gives us opportunities then to say to people even after their diagnosis of cancer that they still can reduce their risk of second cancer or reduce their risk of chronic diseases. (Walker and Terry, 2021)

Addressing Disparities and the Social Determinants of Health

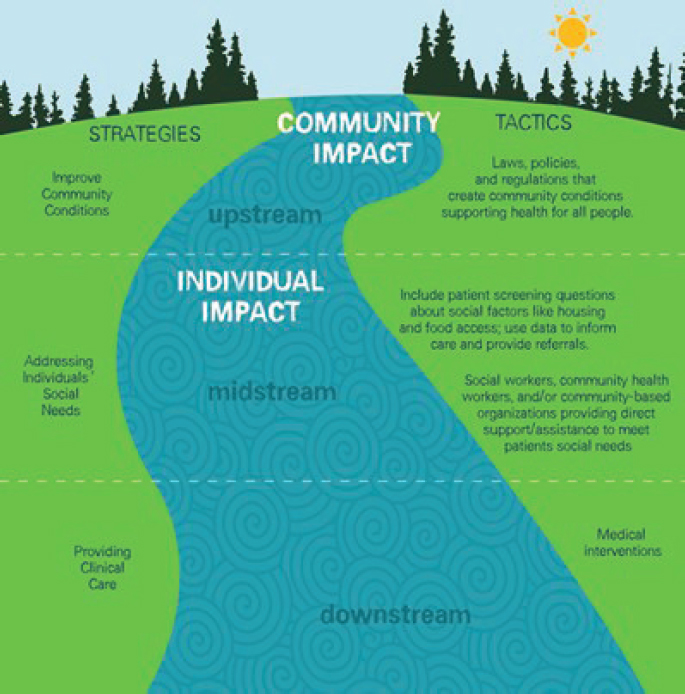

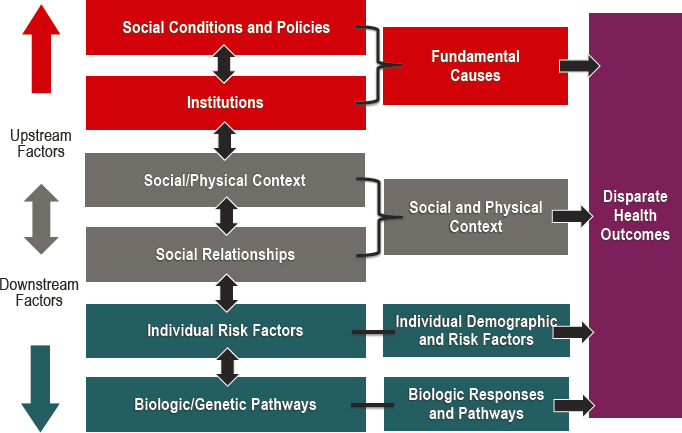

The effects of social determinants of health on cancer risk and patient outcomes were described by Chanita Hughes-Halbert, vice chair for research, professor, and associate director for cancer equity at the University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center. She said that cancer health equity research and interventions to address health disparities stemming from social determinants of health have continued to move upstream to place more emphasis on prevention at the community level (see Figure 1). She cited the Healthy People 2030 goal: “Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and well-being for all.” 10

___________________

10 The social determinants of health “are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.” See https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed April 16, 2023).

SOURCES: Hughes-Halbert presentation, June 27, 2022 (Castrucci and Auerbach, 2019).

Patel noted that there are numerous policy issues regarding the built environment in a community that can influence access to evidence-based interventions for cancer prevention. For example, she said that the ability to exercise outdoors safely is not afforded to everyone equally. Focusing on those policy levers could enable more equitable progress and health outcomes.

Moving forward, Hughes-Halbert said that transdisciplinary research approaches are needed to integrate biological, social, psychological, and clinical factors. For example, Hughes-Halbert presented the stress process model that describes the potential mechanisms of how exposure to stress can affect physical and mental health outcomes and helps explain health

disparities related to social characteristics, personal resources, and social resources (Turner, 2013). She advocated for the creation of multiregional consortia that bring together academic institutions and community-based organizations for translational research.11 Hughes-Halbert highlighted the importance of conducting research on allostatic load—a marker of how social and psychological stressors affect biological functioning—and added that there are many unknowns about how allostatic load influences disease processes (Hughes-Halbert et al., 2020). She said that the electronic health record (EHR) has been used to determine allostatic load, but more precise tools and methods are needed to accurately assess the biological effect of allostatic load, as well as the contributions of systemic factors such as structural racism.

Examples of Innovations in Cancer Etiology Research to Inform Prevention

Cancer is etiologically complex,12 said Timothy Rebbeck, professor of cancer prevention and director of the Zhu Family Center for Global Cancer Prevention at Harvard University, and associate director of equity and engagement at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. This complexity leads to heterogeneity in the causal pathways for cancer, as well as in disease phenotypes. For example, different etiological pathways may lead to the same disease phenotype. Alternatively, the same risk factor could result in multiple distinct disease phenotypes. Because of this complexity, Rebbeck said that there will not be a “one-size-fits-all” approach to prevention interventions, and that different timing and modes of prevention efforts will need to be considered across the spectrum of potential interventions (e.g., those targeted at the neighborhood level, health care and policy change, chemo-prevention, screening and early detection) (Lynch and Rebbeck, 2013).

He emphasized that equity does not mean that everyone should receive the same prevention intervention; instead, the intent should be on developing interventions that result in equity in outcomes for all people. Gwen

___________________

11 For more information about the Medical University of South Carolina’s Trans-disciplinary Collaborative Center in Precision Medicine and Minority Men’s Health, see https://hollingscancercenter.musc.edu/research/transdisciplinary-collaborative-center-precision-medicine-minority-mens-health (accessed October 3, 2022).

12 Etiology is the cause or origin of disease. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/etiology (accessed April 17, 2023).

Darien, executive vice president for patient advocacy and engagement at the National Patient Advocate Foundation, agreed with Rebbeck that a one-size-fits-all approach to cancer prevention interventions is not appropriate and that the goal is equal outcomes, not equal interventions.

Rebbeck also stressed the need for datasets that include representation from diverse populations. These robust datasets will help researchers to better understand etiologic complexity in order to develop interventions that can benefit all populations.

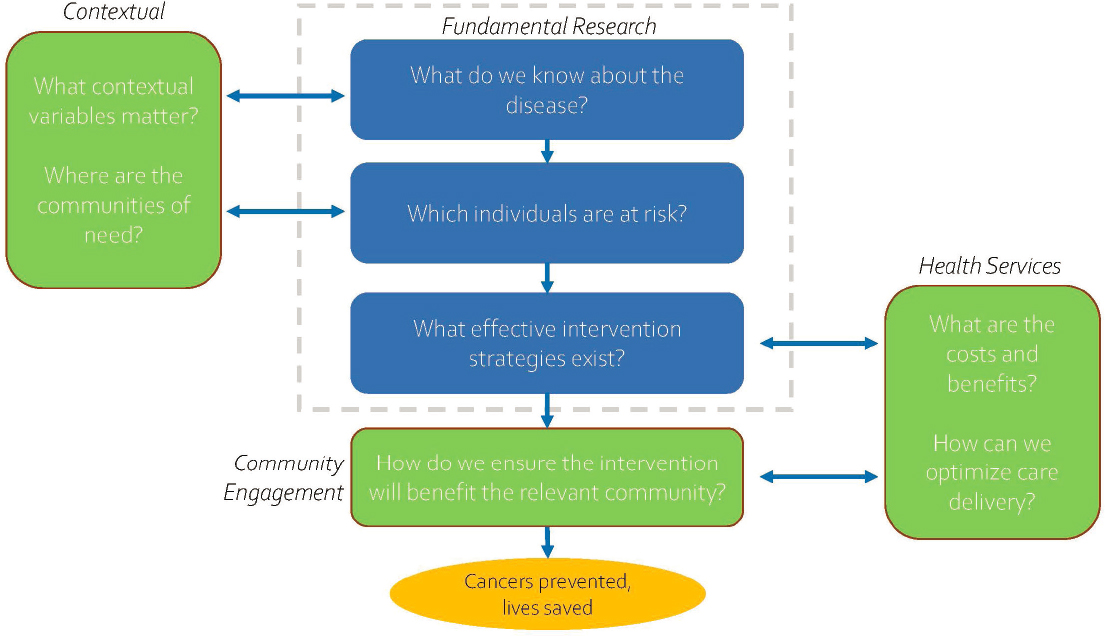

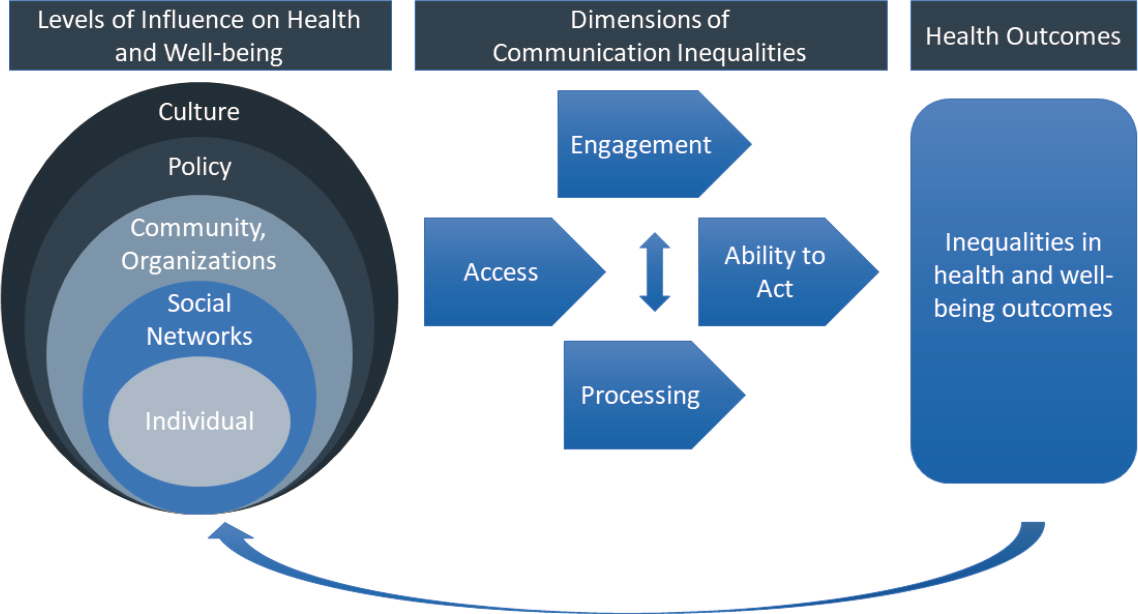

Rebbeck shared a multisector framework to guide potential interventions based on risk and context (see Figure 2). To improve progress in cancer prevention for all people, Rebbeck suggested the following three strategies:

- Developing universal interventions informed by diverse, representative datasets and a better understanding of health disparities.

- Prioritizing and funding the conduct of large, long-term studies.

- Promoting innovation by leveraging novel technologies and methods.

Rebbeck noted that the field of prevention continues to shift from broad population-based efforts toward stratified adaptive and dynamic approaches that are more tailored to specific individuals, embedded within communities, outside of clinical care settings.

Anderson added that there are population-level methods for communication about cancer risk, but she suggested these be paired with individually tailored risk-reduction strategies, based on patient-specific information on cancer risk.

POPULATION-BASED CANCER PREVENTION STRATEGIES

Many speakers discussed potential opportunities to facilitate population-based cancer prevention, including implementation of existing strategies, as well as innovative strategies in development.

Examples of Existing Population-Based Cancer Prevention Interventions

Several speakers reviewed the use of digital tools, evidence-based policy, building community capacity, and community outreach and engagement.

SOURCE: Rebbeck presentation, June 27, 2022; adapted from Rebbeck, 2014.

Digital Tools

Digital tools—used correctly—have the potential to efficiently deliver multiple cancer risk-reduction strategies, said Abby C. King, the David and Susan Heckerman Professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Population Health and Medicine at Stanford University. Technology enables real-time data capture; the delivery of personalized, contextually relevant public health messaging timed for maximal impact; learning over time to better tailor what strategies work best under what contexts; and population-level reach. King said that there is a growing evidence base on digitally delivered behavioral interventions—such as telehealth, mobile apps, and personal digital coaches—among diverse populations (King et al., 2007, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2020). Some of these interventions have been shown to be as effective as human-delivered programs. However, King said that despite the potential of digital tools, their use is still underdeveloped and implementation has been challenging. For instance, many digital interventions do not take advantage of the behavioral research evidence base, and many evidence-based interventions have not been implemented or broadly disseminated. Among interventions that are implemented, many don’t reach underresourced communities that could especially benefit, or these interventions are inadequately tailored to the specific needs of vulnerable communities (Hesse et al., 2021; King et al., 2013, 2016).

King suggested directly involving community members and community organizations, especially those from diverse communities and backgrounds, in the scientific process to demystify science, make science more accessible and inclusive, and promote health equity. For example, King described a community-engaged citizen science initiative, Our Voice, which enables community members to evaluate their environment and initiate environmental changes in their communities through a facilitated four-step process.13 An accessible mobile app enables community members to rate and comment on various features of their community environment, and then community members partner with researchers, community organizations, and decision makers to discuss and prioritize their data, share information, and identify and enact realistic solutions (King et al., 2019).

King described several opportunities to improve the creation and use of digital community-based tools:

___________________

13 For more information on Our Voice and citizen science, see https://med.stanford.edu/ourvoice.html (accessed October 4, 2022).

- Funders could shorten the submission-to-funding cycle to better fit fast-paced digital innovation and build additional funding support for dissemination and scale-up.

- National and community organizations could inform grantees and constituents about evidence-based interventions and encourage the development of partnerships with universities to facilitate uptake of evidence-based strategies.

- The private sector could seek partnerships with academic institutions to improve the quality and effectiveness of digital tools.

- Community members could look for opportunities to become involved in science to increase the variety of, and improve the implementation of, evidence-based solutions.

Using Evidence-Based Cancer Prevention

Policies that affect health—for better or worse—are developed and implemented every day, noted Karen M. Emmons, professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University. She said that public policies affect health by creating and regulating public goods, regulating natural resources, protecting people through mandates and requirements, providing direct support to individuals (e.g., food), and creating opportunities and incentives (e.g., education).

Emmons said evidence-based policies for cancer prevention can improve health outcomes, pointing to state and national tobacco policies that resulted in a significant reduction in smoking rates. For example, when Medicaid began covering comprehensive tobacco cessation treatment in Massachusetts, the tobacco use rates among individuals with Medicaid coverage decreased by 26 percent in the first 2 years of the program (Land et al., 2010b), and hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarctions decreased by 46 percent (Land et al., 2010a). Similarly, she said several national policies targeting tobacco use from 2009 to 2015 led to a more rapid decrease in smoking prevalence in the United States compared to previous years. These policies included tobacco cessation treatment as a free essential benefit under the Affordable Care Act, an increase in the federal excise tax to $1.01/pack, and new Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority to regulate tobacco products (Fiore, 2016).

Emmons underscored the importance of concerted policy efforts to decrease rates of tobacco use, such as decreasing nicotine levels in

cigarettes,14 providing comprehensive insurance coverage of tobacco cessation treatment, and ensuring tobacco-free indoor air. However, she noted that only 50 percent of U.S. states currently provide comprehensive Medicaid coverage of tobacco cessation treatment.15 Comparing the effect of different tobacco control policies among states and municipalities can also elucidate the effectiveness of various strategies, said Emmons.

In addition to tobacco control policies, she said alcohol sales control, the availability of healthy food, and paid sick leave for preventive care are also important aspects of cancer prevention efforts. She emphasized the need for comprehensive, holistic cancer risk-mitigation efforts rather than a piecemeal approach.

Building Community Capacity

Reducing cancer inequities among African American women by increasing routine breast and cervical cancer screening and follow-up care is the overall goal of the National Witness Project, said Detric (Dee) Johnson, project director and member of the board of directors for the organization. The National Witness Project was designed to address barriers to care, cancer stigma, and discrimination. Lay health advisors and community members are central to the program—these credible messengers provide resources, education, and help with patient navigation (Erwin et al., 1996).

Johnson said that over the past 30 years, the National Witness Project has been implemented in 40 sites across 22 states, involving more than 50 volunteers and reaching more than 15,000 women per year. The success and sustainability of the project has been due to its focus on building multilevel community capacity, including at the level of lay health advisors, social networks, and community organizations.

The key to building capacity is a tailored, engaged, and dynamic strategy, rather than a static one-size-fits-all tool kit, said Rachel Shelton, associate professor, codirector of the Community Engagement Core, and director of the Implementation Science Initiative at Columbia University

___________________

14 See FDA proposed rule https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=202204&RIN=0910-AI76 (accessed October 4, 2022).

15 See https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/factsheets/medicaid/Cessation.html (accessed October 4, 2022).

(Shelton et al., 2017). For example, the “train the trainer” model builds capacity onsite and is tailored to specific contexts.16

Shelton said that contextual factors are central to project sustainability. These factors include policy alignment, bidirectional partnerships with community and academic organizations, and external funding availability, especially funders that value and prioritize equity (Shelton et al., 2016, 2017). For example, Shelton said sites that had active partnerships were able to adjust their goals and funding during the COVID-19 pandemic to remain active. Institutional commitment is critical to building trustworthiness with community partners and requires long-term investment (Shelton et al., 2021). Holding institutions accountable to collect and return meaningful and actionable data to community organizations is also key, Shelton said.

Echoing King’s comments, Shelton said including diverse populations in the scientific process would lead to more trustworthy and relevant clinical practice guidelines. She also suggested maximizing the social, financial, and personal benefits that lay health advisors and cancer survivors gain to improve retention in the National Witness Project. For example, such benefits can be increased through ongoing training, which provides career development opportunities and social capital.

Community Outreach and Engagement

Robin C. Vanderpool, branch chief of health communication and informatics research at NCI, discussed the community outreach and engagement requirement in NCI P30 cancer center support grants (CCSGs).17 Vanderpool noted that NCI-supported Clinical and Comprehensive Cancer Centers are required to serve a specific catchment area, which is a self-defined, population-based geographic area (e.g., using census tracts, zip codes, county or state lines, or other geographic boundaries) that the center serves or intends to serve in the research it conducts, the communities it engages, and the outreach it performs. Vanderpool noted it must include the area from which the center draws the majority of its patients, but may extend beyond that, and it must include the local area surrounding the

___________________

16 See https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/professional_development/documents/17_279600_TrainersModel-FactSheet_v3_508Final.pdf (accessed January 31, 2023).

17 See https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-21-321.html and https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/research-emphasis/supplement/coe (accessed April 22, 2023).

cancer center. In a recent mapping of the catchment areas18 of 63 out of 71 designated NCI cancer centers, Vanderpool reported that they cover nearly 88 percent of the U.S. population and have the potential to make a difference locally and at a population level in reducing the cancer burden and mitigating disparities (DelNero et al., 2022).

Vanderpool said that the outreach and engagement component of CCSGs asks cancer centers to define the cancer burden in their catchment area (e.g., cancer incidence and mortality, rates of tobacco use, the prevalence of obesity, HPV vaccination rates, screening rates), as well as the sociodemographic, neighborhood, and environmental characteristics in which their constituents live. Based on this information, cancer centers are then expected to consider how their strategies for outreach and research can reduce the cancer burden, by nurturing bidirectional community-research partnerships and implementing cancer control strategies. Vanderpool said that the primary metric in evaluating the strength of a cancer center’s community outreach and engagement is the scope, quality, and effect of the center’s activities on the burden of cancer in its catchment area.

Vanderpool pointed to a number of publications describing cancer centers’ catchment areas, community outreach and engagement efforts, and how cancer centers are promoting health equity within their mission (Blake et al., 2019; Doykos et al., 2021; Hiatt et al., 2022; Tai and Hiatt, 2017).

Vanderpool said that by “harnessing the collective [actions] of all the cancer centers and their community outreach and engagement efforts, their research efforts, and all the work that is going on in those catchment areas with their community partners, we have the great potential to reduce cancer incidence, morbidity, and mortality at the local and population levels.”

There are important trade-offs to consider when cancer centers define catchment areas, said Julie Gralow, chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. There can be an incentive to more narrowly define a catchment area, to improve metrics for CCSG renewal evaluations (e.g., clinical trial accrual), but this also contributes to areas of the country that are not covered by a cancer center catchment area, particularly rural communities. “I think we need a better balance of what we are rewarded for and what we get credit for community outreach and engagement,” said Gralow. Lawrence Shulman, deputy director for clinical services of the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center, agreed, and added that his cancer center influences a much larger area that does not fall into the

___________________

18 See https://gis.cancer.gov/ncicatchment/app/ (accessed May 22, 2023).

NCI-defined catchment area. “I just wonder whether there would be some sort of incremental rating, where you get some credit for moving further away…really encourag[ing] us to grow out rather than us worrying about how we are going to get scored in our next CCSG renewal,” Shulman said.

Vanderpool responded that some cancer centers are defining emerging or secondary catchment areas. She noted that this is an area of active discussion, especially considering the tension among available resources, the size of community outreach and engagement programs, and the geographic and population size of the catchment areas.

Examples of Innovative Strategies for Population-Based Cancer Prevention

Several speakers suggested innovative strategies for population-based cancer prevention. These included partnerships between academic institutions and community organizations, workplace cancer risk reduction, at-home HPV testing, and the 2-1-1 helpline.19

Academic-Community Partnerships

The importance of creating partnerships between academic institutions and community organizations was discussed by Ruth Rechis, director of the Be Well Communities at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The Be Well Communities program is a place-based strategy that focuses on cancer prevention and control (Rechis et al., 2021), applying strategies such as those from the Health Impact in 5 Years initiative20 of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). One of the Be Well Communities Rechis described is implemented in partnership with Acres Homes,21 a historically African American community in Houston. The project involves 50 organizations that developed a community action plan to promote active living, healthy eating, and preventive care. Some of the interventions implemented included safe walking paths to schools, physical activity classes, gardens, and nutrition

___________________

19 See https://www.211.org/ (accessed January 31, 2023).

20 See https://www.cdc.gov/policy/opaph/hi5/index.html (accessed January 31, 2023).

21 For more information on Be Well Communities, see https://www.mdanderson.org/research/research-areas/prevention-personalized-risk-assessment/be-well-communities.html (accessed October 6, 2022).

educational programs, all while focusing on building trust within the community and actively incorporating community needs and feedback into the implementation process.

Cancer Prevention in the Workplace

Cancer risk-reduction strategies can be especially effective when delivered at the workplace, since a majority of adults under 65 spend most of their days working, said Peggy Hannon, director of the Health Promotion Research Center and professor in the Department of Health Systems and Population Health at the University of Washington. Almost half of all U.S. employees work for small businesses, which are less likely to offer funding for wellness. Hannon noted that this is an important health equity issue because employees of small businesses are especially at risk for disparities in health outcomes—they are more likely to be working at low-wage jobs and less likely to have health insurance (Harris et al., 2021).

Hannon clarified that health promotion information can be either spread within the workplace setting or the workplace itself can be a target of intervention to promote healthy habits. Interventions can also employ both of these strategies. Hannon described the Connect to Wellness program, which encourages small worksites to adopt and implement evidence-based interventions targeting cancer screening, healthy eating, stress reduction, vaccine education, tobacco use, and physical activity.22 The Connect to Wellness program and tool kits have been shown to significantly increase and sustain the adoption of evidence-based interventions by small businesses in several studies, including a randomized controlled trial (Hannon et al., 2019).

Hannon noted that the pandemic created new challenges for the program, including a loss of staff and funding for workplace interventions and a shift to remote work for a portion of the workforce. In addition, there was a need to prioritize stress-related interventions and incorporate COVID-19 vaccination into workplace settings. Hannon said that facilitating collaboration among local health departments and small businesses has been one tactic used by the Connect to Wellness program to overcome some of the challenges related to the pandemic.

___________________

22 For more information on the Connect to Wellness program, see https://depts.washington.edu/hprc/programs-tools/connect-to-wellness/ (accessed October 6, 2022).

HPV Self-Collection

Cervical cancer illustrates the pervasive inequities in cancer prevention and care, said Jane R. Montealegre, assistant director of community outreach and engagement at the Dan L. Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center and assistant professor of pediatrics and hematology/oncology at Baylor College of Medicine. Although there are effective interventions for prevention, early detection, and treatment for cervical cancer, the burden of cervical cancer is not equally distributed: 90 percent of cervical cancer diagnoses occur in low- and middle-income countries (Hull et al., 2020), and in the United States, individuals living in areas of low socioeconomic status have higher rates of cervical cancer diagnoses and lower rates of cervical cancer screening compared to individuals living in areas of high socioeconomic status (Deshmukh et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022).

Montealegre said that “after many decades of dramatic declines in cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, we have unfortunately over the past several decades reached the point of plateau, or stagnation.”

She added that cervical cancer screening rates have also declined, and she said that current interventions to increase clinician-delivered cervical cancer screening are inadequate to overcome the current barriers women face in accessing primary health care and cervical cancer screening (Suk et al., 2022). These include financial, cultural, and informational barriers, said Montealegre. Some women living in low-socioeconomic communities in the Los Angeles area have misconceptions that cervical cancer cannot be cured, which undermines prevention and early detection efforts, added Beth Karlan, professor and vice chair of Women’s Health Research in the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of cancer population genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. Karlan emphasized the need to partner with communities to increase health literacy and address the psychosocial factors that influence women’s willingness to participate in cancer prevention activities.

Montealegre said that in the short term, the incidence of cervical cancer would decline more rapidly in the United States by increasing screening than by increasing HPV vaccination (Burger et al., 2020). An innovative approach to cervical cancer screening is the self-collection of a sample for testing by women at home who are at high risk of HPV. She said that this method of high-risk HPV testing has high sensitivity and high negative

predictive value,23 and has been shown to increase the rates of cervical cancer screening among women who have not previously been screened for cervical cancer (Montealegre et al., 2015). She said that some countries are already partially or exclusively using self-sample HPV tests but noted that numerous barriers to self-testing remain, including the need for FDA approval of test kits. There is also a lack of U.S.-based clinical trials assessing the efficacy of self-tests. Montealegre cautioned that self-test kits need to be combined with appropriate health education and follow-up care. Gralow highlighted health insurance reimbursement as another challenge to wider uptake, because there is no billing code associated with self-tests, as there is for clinician-collected tests.

A randomized clinical trial found that mailing HPV kits, in addition to usual care (e.g., annual reminders and outreach from primary care), to patients in the United States who were underscreened for cervical cancer resulted in increased screening uptake compared to patients who only received usual care. No significant differences in precancer detection or treatment were identified (Winer et al., 2019). Montealegre is conducting a trial to assess the effect of HPV self-collection in the context of a U.S.-based safety net health care setting; this trial is combining self-testing with culturally competent patient navigators and educators (Montealegre et al., 2020).

Self-testing cancer screening needs to consider the whole continuum of the screening process, said Carol M. Mangione, chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and chief of the Division of General Medicine and Health Services Research at the University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine and the Fielding School of Public Health. For example, for people who may not have a usual source of care, how can they participate in shared decision making and get connected to follow-up care, if needed? Castle added that evaluating the efficacy of self-testing among wider populations is crucial and noted that research is also needed on the components of the test kits (e.g., liquid mediums and swabs).

___________________

23 The likelihood that a person who has a negative test result indeed does not have the disease. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/negative-predictive-value (accessed May 15, 2023).

2-1-1 Collaboration for Cancer Prevention Equity

Opportunities to use the 2-1-1 helpline for cancer prevention,24 especially among vulnerable populations, were discussed by Maria E. Fernández, professor of population health and implementation science, director of the Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research, and codirector of the Texas Institute for Implementation Science at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. The 2-1-1 helpline covers 96 percent of the U.S. population, connecting individuals to social and health services through calls, texts, and emails. The helpline also enables the collection of anecdotal, systematic, qualitative, and quantitative data, but Fernández said this resource is often underused in research. An NCI-funded research supplement in 2012 recommended that organizations collaborate with 2-1-1 in order to create systematized methods and measurements that allow for 2-1-1 data integration and use (Hall et al., 2012). For example, the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network collated data from several 2-1-1 sites across the United States to assess the need for cancer prevention interventions, as well as the willingness of people to answer questions regarding their risk-reduction needs (White et al., 2019). Fernández said it is feasible to embed patient navigation interventions within the 2-1-1 helpline (Kreuter et al., 2012). One study is using the 2-1-1 helpline to promote healthy eating habits for families (Kegler et al., 2016). Despite the promise of 2-1-1 for cancer prevention interventions, she noted that challenges, such as sustainability and the ability to scale up, need to be overcome. Fernández also emphasized the need for systematic planning, such as using implementation mapping for the training of 2-1-1 specialists and navigators.

Fernández suggested that the innovations stemming from the COVID-19 response can be applied to cancer prevention (Castle, 2021). For example, she said the use of geospatial modeling to identify small geographic areas with inequities and social network analyses can aid in understanding how and where best to implement interventions.

___________________

24 The 2-1-1 helpline is a nationally designated three-digit telephone exchange connecting callers to health and social services within their community. 2-1-1 helplines are operated by state and local systems, often in partnership with local public or private agencies. See https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/dial-211-essential-community-services (accessed October 7, 2022).

Funding and Long-Term Partnerships for Prevention

Many workshop participants highlighted the challenges of implementing population-based cancer prevention interventions, including maintaining funding and long-term partnerships. King stated that funding is a continuous challenge and suggested diversifying the funding partners to include community governments, foundations, and private-sector organizations to meet the financial needs of programs. Hannon suggested additional availability of nonsiloed funding mechanisms to support multilevel strategies for cancer risk reduction. Rechis agreed that flexible funding was especially important when tailoring interventions to community needs and priorities. Additionally, Rechis and Fernández said that funding opportunities that encourage collaboration with communities would foster community trust and provide access to evidence-based cancer prevention strategies.

Johnson also agreed that funding is a major challenge and said that academic institutions need to make an active effort to partner with community organizations. Shelton called for a change in funding structures, specifically the creation of formal funding mechanisms that value community engagement, such as the community outreach and engagement requirement for CCSGs that Vanderpool described. Emmons added that these grants are starting to be used in combination with other federal funding mechanisms, such as the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) federally qualified health centers.

Emmons emphasized that funding for research and the evaluation of policies is inadequate, especially for small-scale policies implemented at the municipal and organizational levels. She noted that these types of policies can be especially important to creating large-scale change, such as that of the Tobacco 21 campaign.25

Shelton noted that community engagement, co-creation, and continual learning need to be central to partnerships for cancer prevention. She recommended that community engagement and equity be embedded within cancer prevention research—especially in the early stages—to ensure that the resulting research findings take into account the characteristics of the communities that are most affected by cancer and structural inequities. Vanderpool agreed and added that building trust and trustworthiness takes significant time and effort to achieve.

___________________

25 See https://tobacco21.org/ (accessed January 31, 2023).

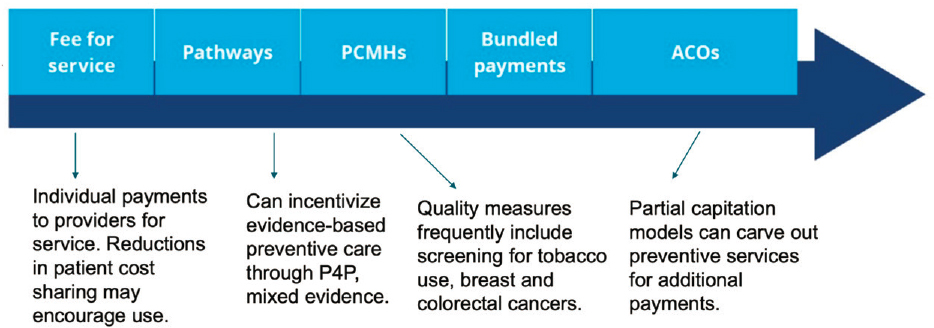

CLINIC-BASED CANCER PREVENTION STRATEGIES

Gralow noted that clinic-based cancer prevention strategies complement population-based interventions. Several speakers discussed existing strategies for clinic-based cancer prevention, as well as innovations in the field.

Role of the USPSTF in Clinic-Based Cancer Prevention

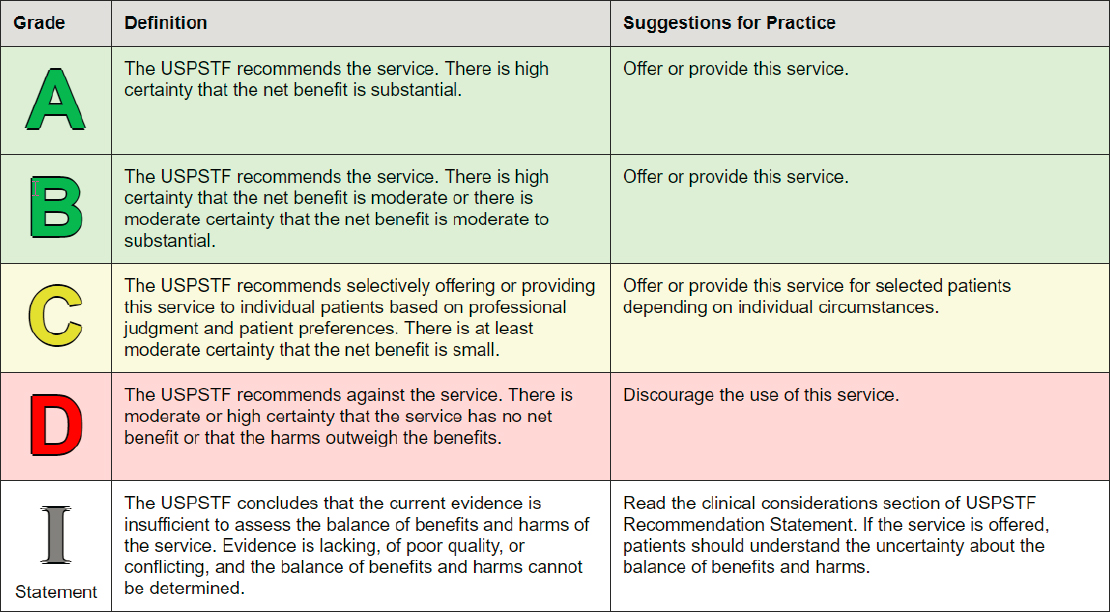

The USPSTF is an independent panel that makes evidence-based recommendations about clinical preventive services,26 including screening, counseling, and preventive medications, said Mangione. There are more than 80 USPSTF recommendations. To determine a recommendation grade, she explained, the USPSTF assesses the available evidence, including the certainty and magnitude of benefits and harms, but it does not conduct new research. The USPSTF provides grades for its recommendations, depending on the strength of the evidence base (see Figure 3).

Mangione said that one of the challenges the USPSTF faces is the existence of gaps in the evidence base, which can lead to USPSTF extrapolation of recommendations to populations who were not included in original intervention trials. In 2021, the USPSTF called attention to high-priority evidence gaps related to health equity in cardiovascular disease and cancer prevention.27 The report concluded the following:

- Future research may result in important new recommendations or help inform policy to improve access to and use of these preventive services, reduce disparities in health care, and increase health equity.

- Identifying evidence gaps and highlighting them as research priorities will inspire public and private researchers to collaborate and target their efforts to generate new knowledge, address important health issues, and improve health equity.

Mangione noted that the evidence-based threshold for the 2013 USPSTF recommendation for lung cancer screening was exacerbating health disparities. Aldrich and colleagues (2019) found striking screening eligibility differences based on race: while 37 percent of White individuals

___________________

26 See https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ (accessed April 23, 2023).

27 See https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/inline-files/2021-uspstf-annual-report-to-congress.pdf (accessed April 23, 2023).

SOURCES: Mangione presentation, June 27, 2022 (USPSTF, 2018).

who smoked and were diagnosed with lung cancer were never eligible for screening, 67 percent of Black individuals who smoked and were diagnosed with lung cancer were ineligible for screening based on the USPSTF recommendation. Mangione noted that screening for lung cancer in people with lighter smoking histories, and at an earlier age, may help partially ameliorate racial disparities in screening eligibility. Based upon more recent data from clinical trials and observational studies, the USPSTF updated its guidelines in 2021 to lower the eligibility age to 50 years and to lower smoking history to 20 pack-years (USPSTF, 2021).

Mangione highlighted important evidence gaps for various cancer screening recommendations (see Box 3). Overall, she said the evidence gaps are largely driven by lack of access to behavioral interventions, medications, screening tests, and treatment, with the highest-risk populations having the most limited access.

Examples of Existing Clinic-Based Cancer Prevention Interventions

Several speakers discussed HPV vaccination, tobacco cessation, physical activity and nutrition, and working at the intersections of community health and primary care.

HPV Vaccination

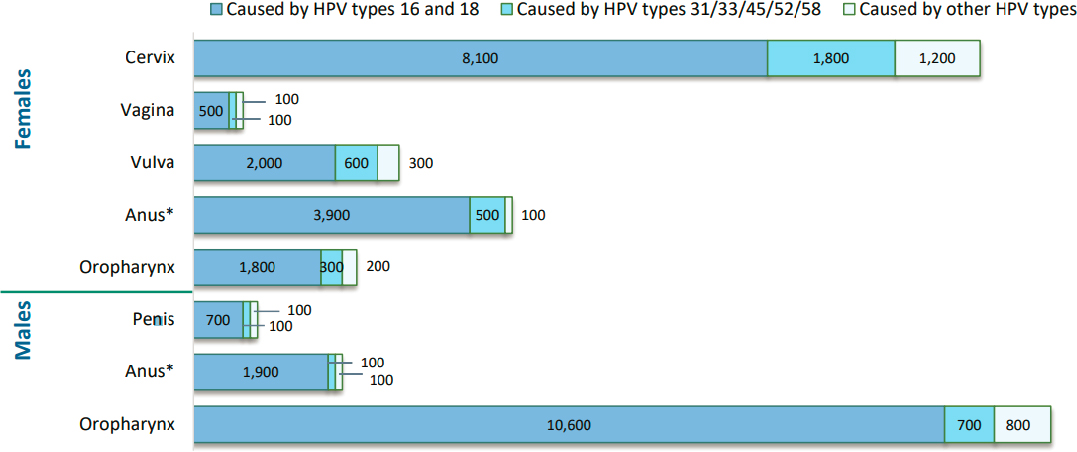

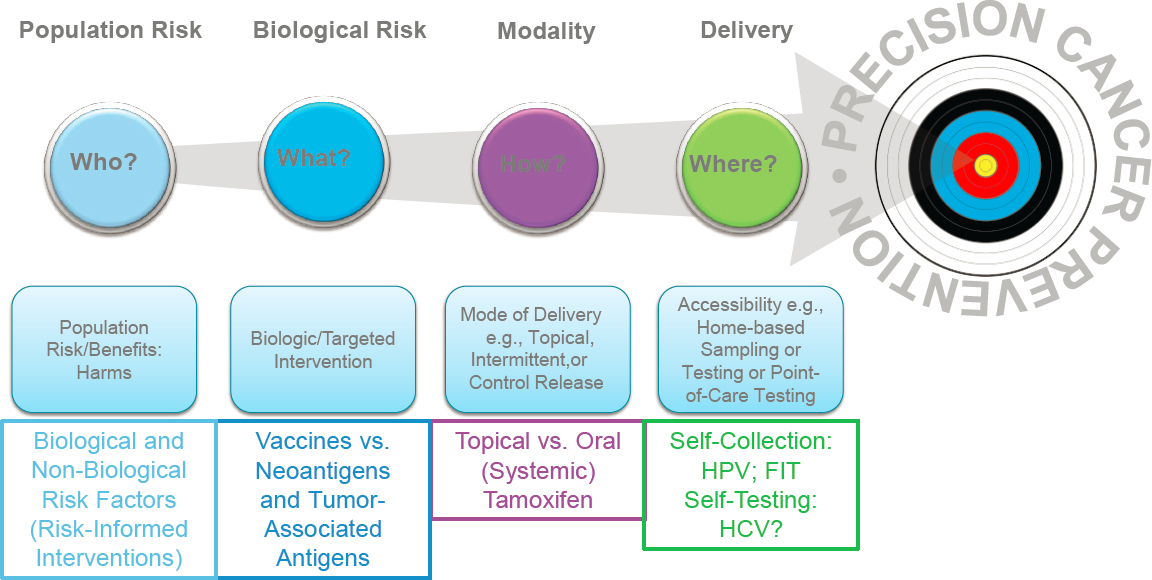

There are approximately 46,000 HPV-attributable cancer diagnoses per year in the United States, said Douglas Lowy, principal deputy director of NCI (see Figure 4).28

___________________

28 See https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no26-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2014-2018.htm#:~:text=Based%20on%20data%20from%202014,and%20about%2020%2C424%20among%20men (accessed April 23, 2023).

* Includes anal and rectal squamous cell carcinomas.

SOURCES: Lowy presentation, June 27, 2022, and https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no26-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2014-2018.htm (accessed April 23, 2023).

Lowy said there are currently three different vaccines approved in the United States to protect against several different strains of HPV, with Gardasil-9 being the vaccine currently available in the United States. Lowy said current recommendations for HPV vaccination include the following:29

- 9–14 year olds: routine vaccination, 2 doses.

- 15–26 year olds: routine catch-up vaccination, 3 doses.

- 27–45 year olds: participate in shared decision making for vaccination, 3 doses.

Lowy noted that there has been progress in increasing HPV vaccination among teens 13–17 years old, but that the target of 80 percent vaccination coverage has not been met (Rosenblum et al., 2021). After 10 years of approval, he noted that safety data have been reassuring, with no confirmed safety issues identified (Gee et al., 2016).

Lowy said a study in Denmark found an approximately 90 percent decrease in cervical cancer incidence from 2006 and 2019 among women who received the vaccine when they were 16 or younger (Kjaer et al., 2021). Overall, HPV vaccines induce high and durable efficacy against incident infection and disease caused by the various HPV types accounted for in the vaccines, said Lowy. But they are most effective when administered prior to sexual debut. To improve uptake of HPV vaccines, researchers are evaluating the efficacy of a single HPV vaccine dose (Barnabas et al., 2022; Kreimer et al., 2020; Porras et al., 2022).

Vanderpool asked Lowy about the stagnated uptake of the HPV vaccination, and what advice he had to improve vaccine coverage. Lowy replied that this is a complex, multifactorial problem, and voiced concern that the politicization of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccines may have a serious negative effect on the continued uptake of the HPV vaccine. Lowy added that the HPV vaccine is largely not required for school entry, which further threatens vaccine uptake. “Although vaccination is very important, if you had a choice of either increasing screening or increasing vaccination, I would try to increase screening because you will have a faster impact on reducing the incidence of cervical cancer. It will not have the impact on the other cancers, however,” Lowy said.

___________________

29 See https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html (accessed May 16, 2023).

Tobacco Cessation

There is a considerable gap between the evidence for tobacco cessation treatment and the translation of these services into practice, said Kristie Long Foley, professor and chair, Department of Implementation Science, and senior associate dean for research at Wake Forest School of Medicine. Even with the landmark publication30 in 1979 calling for patients to quit smoking, she said that a study in 2015 found that only 70 percent of patients who visited a health professional were advised to quit smoking (Khan et al., 2021). We have the evidence to help patients quit, she said, but we are not providing the help patients need through existing systems.

She said three of the five A’s of treating tobacco use and dependence—ask, advise, assess—are relatively easy to implement in the clinical setting. The other two A’s—assist and arrange—can be more challenging to implement and involve varying amounts of effort and time commitment.31 To optimize implementation, she suggested determining what is feasible, engaging staff and decision makers in strategic planning, and designing for sustainability (Powell et al., 2012).

Foley said that the goal is to increase the reach of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatment by using implementation science principles to adopt and integrate these practices in clinical and community settings. Increasing reach is critical and essential for equity, she added, and there are still significant geographical disparities in access to resources to support tobacco cessation. Foley said that the health care setting is the place with the greatest opportunity to assist patients with tobacco cessation, but only one in three patients who see a health professional receive medication or counseling support.32 Before moving forward with programs, she suggested clinics ask questions such as, “What is the willingness and capacity to help patients quit smoking at the point of care?” and “Does your health system have a centralized tobacco cessation resource?”

She shared examples of policies to help make the choice to quit smoking easier for patients, including combining clinic-level support with access to proactive quit lines; providing optimal insurance coverage to reduce

___________________

30 See https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/nn/feature/public (accessed May 16, 2023).

31 For more information on the five A’s, see https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/references/quickref/tobaqrg.pdf (accessed April 23, 2023).

32 See https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/sgr/2020-smoking-cessation/fact-sheets/healthcare-professionals-health-systems/index.html (accessed October 17, 2022).

out-of-pocket costs for people trying to quit; implementing public health messaging campaigns; and enforcing clean air laws and tobacco taxes to create environments conducive to cessation.

Foley emphasized that pre-implementation planning is essential for implementing clinic-based prevention strategies and needs to include a strategy for engaging patients and the health care team. She also suggested conducting ongoing evaluations to enable real-time learning and adaptation as implementation unfolds.

Physical Activity and Nutrition

The evidence base on physical activity and nutrition and cancer risk was reviewed by Anne McTiernan, professor of epidemiology at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and University of Washington Schools of Public Health and Medicine.33 The 2018 U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report found that, for several types of cancers, there was strong evidence that physical activity was associated with a reduced risk of cancer, varying between 12 and 20 percent relative risk reduction.34

McTiernan said the U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines call for adults to obtain 150–300 minutes of moderate physical activity per week (or 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity/week, or equivalent combination throughout the week); for adults 18–64, muscle strengthening activities are recommended at moderate or greater intensity (all muscle groups) on 2 or more days a week. Adults over age 65 should aim for the same as younger adults, or be as active as abilities and health conditions allow, and include balance training and combination activities (e.g., strength and aerobic training together).

While few studies have assessed the effect of increased physical activity on cancer risk for someone who was sedentary, randomized controlled trials have shown a reduction in cancer-related biomarkers for this population (Ballard-Barbash et al., 2012). Similarly, she said studies have examined cancer risk related to body fatness or weight loss, saying there is strong evidence that body fatness increases risk for certain cancers (e.g., postmenopausal breast, colon, endometrial, kidney, liver, and others) (World Cancer Research Fund International and AICR, 2021).

___________________

33 This topic was covered in more detail in prior National Cancer Policy Forum workshops (IOM, 2012; NASEM, 2018).

34 See https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf (accessed October 18, 2022).

Studies have also shown that weight loss and bariatric surgery are associated with reductions in cancer risk (Aminian et al., 2022; Brown and McTiernan, 2020; Yeh et al., 2020).

McTiernan said there is strong evidence that alcohol use increases risk for several cancers, but there is more limited evidence assessing whether alcohol reduction or cessation reduces cancer risk (Ahmad Kiadaliri et al., 2013; Heckley et al., 2011; Jarl and Gerdtham, 2012; Jarl et al., 2013).

To improve the implementation of physical activity and nutrition interventions in clinical settings, McTiernan said that patient access to primary care is crucial, as are adequate clinician time and institutional prioritization of these interventions. There is also a need to better integrate cancer risk-reduction interventions with recommendations for the prevention of other chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, said McTiernan.

She concluded with a proposed list of research questions to improve prevention interventions in clinical settings:

- Can clinic-based interventions (e.g., physical activity, nutrition, weight loss, and alcohol reduction) reduce cancer risk?

- What interventions are effective for specific groups (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, diverse incomes, rural dwellers, persons at elevated cancer risk, cancer survivors)?

- What is the feasibility of these interventions in different primary care settings?

- What is the efficacy of guidance in virtual visits, group clinics (in person or virtual), electronic health monitoring, and EHR-delivered information?

Intersections of Community Health, Primary Care, and Specialty Care

A 2013 Institute of Medicine report characterized the cancer care system as in crisis because of factors such as the fragmented health care system and the failure to use evidence-based practices in care (IOM, 2013), said Shawna Hudson, Henry Rutgers Chair, professor, and research division chief of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and member of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey. Hudson said a continuing challenge is the slow uptake of evidence-based practices in cancer control within primary care settings (Khan et al., 2021). She added that the delivery of evidence--

based cancer prevention interventions is further delayed by multilevel forces both upstream and downstream of the patient’s interaction with a clinician or health care organization (e.g., insufficient social safety nets, fragmented care delivery, lack of interconnected health information technology systems, lack of payer incentives, structural racism, and the built environment) (O’Malley et al., 2021).

Hudson also discussed the need for real-time feedback systems, such as the “plan-do-study-act cycle.” To automate some of this, Mangione suggested using the EHR and decision-support prompts like the University of California, Los Angeles’s Care Gaps, which highlight the cancer screenings a patient might need.

Hudson emphasized that high-quality, clinic-based cancer prevention will require high-quality primary care and highlighted the findings and recommendations from the National Academies report Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care (see Figure 5) (NASEM, 2021a). Hudson said that high-quality primary care will need to be accessible, integrated, equitable, and delivered by teams that are accountable for addressing health and wellness needs across different settings.

Looking more closely at the first three objectives, Hudson emphasized the need for primary care organizations to strongly engage in promoting population health in the communities in which they are providing care and to address community needs that affect health. She said this can be accomplished by doing the following:

- Integrating care delivery in nonclinical settings.

- Partnering with health departments, academic institutions, local governments, and others to create opportunities for screening.

- Having community members involved in care delivery, through mechanisms such as membership on boards and by developing a workforce pipeline that pulls directly from community so the care team reflects the people it serves.

- Thinking more broadly who can deliver cancer prevention services outside of the patient/clinician encounter, including integration of community health workers in primary care teams.

Hudson also discussed workforce challenges and opportunities in the delivery of clinic-based cancer prevention. She shared an example from her cancer center in which they are awarding grants to federally qualified community health centers so each facility can decide how best to hire for their

SOURCES: Hudson presentation, June 27, 2022 (NASEM, 2021a).

own needs, whether it be community health workers or patient navigators. Kasisomayajula Viswanath, the Lee Kum Kee Professor of Health Communication at Harvard University T. H. Chan School of Public Health and at the McGraw-Patterson Center for Population Sciences at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, noted that one strategy to improve access to care is to shift some tasks from scarce, highly credentialed professionals to individuals who may be less credentialed. Hudson responded that the United States has not sufficiently tested shifting tasks to professionals such as radiology technicians, dental hygienists, community health workers, and others, which could be a promising avenue for research on evidence-based strategies for delivery of cancer prevention interventions.

Finally, Hudson highlighted the need to address policies and practices that have contributed to structural racism, and to design learning health systems35 in a way that promotes health equity and dismantles the processes that sustain racial health disparities (Emmons and Colditz, 2017).

Examples of Innovative Clinic-Based Prevention Strategies

Many speakers discussed innovative clinic-based strategies for cancer prevention, including health system strategies, interventions for underserved populations, state health policies, genetic testing for individuals with an elevated risk for cancer, and patient advocacy.

Health System Strategies

Examples of primary prevention strategies at the health care organization level were shared by Lawrence Kushi, director of scientific policy in the Division of Research at Kaiser Permanente (KP) Northern California. Because KP is an integrated health care system, Kushi said that all services available for lifestyle changes, such as wellness coaching or classes, are free for KP members. Using the EHR, KP is also able to evaluate programs to see how and for whom they are beneficial. For example, when examining the telephone wellness coaching program on tobacco cessation, researchers

___________________

35 A learning health system occurs when “science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience.” See https://nam.edu/programs/value-science-driven-health-care/learning-health-system-series/ (accessed June 24, 2023).

found higher quit rates among program participants compared to those who did not participate in the program, and similar rates to those who participated in an in-person class (Boccio et al., 2017). Kushi said patients who participated in wellness coaching via telephone for weight loss had statistically and clinically meaningful reductions in body mass index (BMI) in the year following the start of the program (Schmittdiel et al., 2017). They also found that patients who were overweight were more likely to experience weight loss if they had exercise documented in their medical record as a vital sign (Coleman et al., 2012).

To improve nutrition guidance, Kushi suggested that health care systems should ensure that patients are more routinely asked about healthy eating during clinical visits—specifically about dietary composition, including processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. He emphasized that health care systems play an important role in facilitating strategies to promote cancer prevention, and these lessons can be applied even in other nonintegrated health systems.

Interventions for Underserved Populations

A teams-based framework for engaging communities and a model for assessing population health and health disparities was described by Electra Paskett, the Marion N. Rowley Chair in Cancer Research, director of the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, and associate director for population sciences and community outreach at the James Comprehensive Cancer Center at the Ohio State University (OSU) (see Figure 6). Paskett noted that disparities result from the interaction of many risk factors across multiple levels—from biological pathways to social conditions and policies.

She emphasized that community partners are vital in the cancer center’s work and said that OSU has developed relationships with more than 250 community partners, assisting many organizations in achieving nonprofit 501(c)(3) status.

Paskett said the OSU center has transdisciplinary teams with expertise ranging from molecular biology to behavioral science, using common terminology to be able to speak across disciplines and to work with communities to address the problems together. As one example of their work, she described the Take CARE (Clinical Avenues to Reach Health Equity) study working with ten health systems across four states to test the effectiveness of an integrated cervical cancer prevention program addressing

SOURCES: Paskett presentation, June 27, 2022 (Warnecke et al., 2008).

three behavior areas: tobacco use, HPV infection, and lack of cervical cancer screening.36,37

They have found that deploying implementation science principles, paired with communication, trust, and training, is a successful approach. She also emphasized that building this trust requires a stable presence with community groups and coalitions, and not “helicoptering” in and then leaving based on the grant’s needs. It is also important to listen to the community and adapt plans based on community needs and priorities, Paskett stated.

Paskett said that they have worked with health centers in their communities to help them more effectively use EHRs for cancer screening, but she noted that the lack of follow-up protocols for abnormal test results is a challenge. Paskett added that she is advocating for patient navigation to become a reimbursable service, but it has been challenging to adopt and cover the costs of patient navigation programs within the health care system.

___________________

36 See https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04411849 (accessed February 2, 2023).

37 For more information on cervical cancer prevention programs at OSU, see https://cancer.osu.edu/blog/ohio-state-experts-working-to-reduce-cervical-cancer-rates-in-appalachia (accessed October 21, 2022).

One opportunity is to create procedural codes for patient navigation interventions and have health insurers, such as state Medicaid programs, reimburse these services, said Christopher Cogle, chief medical officer at Florida Medicaid and professor at University of Florida. He noted that coverage of these services will affect Medicaid budgets, so this may require additional discussion about the extra costs needed to compensate patient navigators.

State Health Policies

Cogle described opportunities to influence cancer prevention with policy at the state level. He highlighted three key areas for cancer prevention policy: individual behaviors, systems and environments, and mental health. Cogle noted that almost all of the burden of cancer prevention is placed on individuals to make healthy lifestyle choices, despite the fact that policies and systems strongly influence cancer risk. He also underscored the roles of depression and anxiety in contributing to behaviors that increase the risk of cancer, such as tobacco and alcohol use.

Cogle offered 22 opportunities for cancer prevention, including policy, data, and financial opportunities (see Box 4). In terms of policy, he emphasized the need for stronger state-level cancer plans and the inclusion of cancer prevention in state health improvement plans. He also highlighted the need to address social determinants of health, saying that the cancer prevention efforts will not be successful until the basic needs of individuals are met. For financing, Cogle suggested the creation of procedural codes for cancer prevention interventions, so these can be more easily itemized and reimbursed by insurance.

Genetic Testing for Cancer Risk

Clinic-based approaches and regulatory solutions are available to expand access to genetic testing, which is an important strategy for targeting cancer prevention interventions to individuals at high risk of developing cancer, said Kenneth Offit, chief of clinical genetics service, vice chair of academic affairs in the Department of Medicine, and chair of inherited cancer genomics at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and professor at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Offit said that increasingly companies are directly targeting consumers to offer a range of testing services, including genetic testing for

predisposition to cancer. Offit said that a number of these tests have poor specificity, contributing to false positive results. These false positive test results may lead to unnecessary invasive procedures and may cause patient distress (NASEM, 2020). FDA has the authority to regulate direct-to-consumer tests, but Offit said that enforcement varies based on the test type. Proposed legislation—Verifying Accurate Leading-edge In Vitro Clinical Test Development Act, also known as the VALID Act38—would give FDA authority to regulate all laboratory-developed tests using a new risk-based framework, better aligning oversight authority between FDA and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which administers the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments.39

In addition to regulatory reforms, he suggested genetic testing strategies that can be implemented in clinical settings of care. First, he suggested offering genetic testing to those with a family history of carrying an altered gene that increases cancer risk, or to individuals who are part of a community known to have a high frequency of a cancer gene mutation. Offit said that implementation across community settings of care may be challenging, citing a study finding that 35 percent of participants wanted local clinicians to manage genetic testing and follow-up care, but 60 percent of clinicians said they did not feel comfortable with that or did not want to do so (Morgan et al., 2022).

The second strategy is cascade testing,40 in which an individual with a suspected mutation receives broad-based testing to identify the likely genetic alteration, and then testing for that specific variant is extended to at-risk family members, with the process repeating until all the genetic carriers are identified. Offit estimated that if cascade testing is offered to 15 percent of current patients with cancer, then all carriers of cancer mutations could be identified in less than a decade (Morgan et al., 2022). He referenced a recent study that found clinician phone outreach to at-risk family members increased the completion of cascade testing to nearly 60 percent (Frey et al., 2020) and said several other trials are examining this approach across the country. Using Web-based approaches, cross-country consortiums, and

___________________

38 See https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2369/text?s=1&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22valid+act%22%5D%7D (accessed May 8, 2023).

39 See https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/clia (accessed May 12, 2023).

40 See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/genetics-dictionary/def/cascade-screening (accessed May 8, 2023).

novel remote consultation models, Offit believes that cascade testing could be scaled to identify all individuals with high-risk cancer mutations across the country, giving people advance notice to consider opportunities to participate in risk mitigation interventions.

Karlan noted that inequities exist with this approach, resulting in fewer individuals from underserved populations and fewer men undergoing cascade testing. She said some health systems are trying to take some of the burden off family members to conduct outreach for cascade testing, but this can be challenging for health systems, especially if family members reside in other states.

Patient Advocacy in High-Risk Populations

Several barriers to the delivery of appropriate preventive care for people at high risk of developing cancer were highlighted by Sue Friedman, executive director of Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE), a breast cancer survivor and advocate for the hereditary cancer community, including the following:

- A confusing patchwork of guidelines, regulations, and insurance coverage policies are difficult to navigate and understand.

- Guideline-recommended screening and risk-reduction interventions often have high out-of-pocket costs for patients.

- Limited options exist for reducing risk that are acceptable and affordable to patients.

- Preventive care is often delivered piecemeal and requires individuals to coordinate their own care.

- There are gaps in the evidence base, including for individuals at high risk for developing cancer.

All of these factors are complicated by low health literacy, lack of awareness and understanding about genetics, and inconsistent terminology, said Friedman.

There are also gaps in clinical guidelines and insurance coverage policies, she said. For example, the USPSTF recommendation for genetic test-

ing is limited to BRCA1/BRCA241 tests for women, and excludes panel testing for other genes, men, and people who are currently receiving treatment. Mangione also noted that the scope of the USPSTF is focused on recommendations for persons with average risk without signs or symptoms of disease and does not include disease management recommendations for individuals with above-average or high-risk conditions.42

Furthermore, while the testing itself might be covered, Friedman noted that there is no assessment from the USPSTF of preventive options to manage care for a patient with a high-risk finding once identified, such as breast cancer screening with magnetic resonance imaging, colonoscopies, and risk-reducing surgeries. This contributes to coverage gaps for patients with Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurance, with many patients at high risk of cancer experiencing large out-of-pocket costs for care focused on risk reduction and early detection.

Friedman’s organization, FORCE, focuses on public policy to address gaps in insurance coverage, reduce barriers to care, improve regulation, and prioritize guideline development for people at high risk of developing cancer. The organization also works on improving health literacy by educating the public on genetics and preventive care related to cancer and by addressing the overuse of medical jargon and the increasing challenge of health-related misinformation.43

Friedman shared several priority areas to improve cancer prevention, risk mitigation, and early detection:

- Investing in dissemination and implementation of innovations at a comparable level to the funding for discovery-based research.

- Focusing on developing prevention interventions that are safe, acceptable, and accessible to individuals at high risk of developing cancer.

___________________

41 BRCA1/BRCA2 genes normally help to suppress cell growth, but people who inherit certain mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 genes have a higher risk of getting breast, ovarian, prostate, and other types of cancer. See https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/brca1 and https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/brca2 (accessed May 16, 2023).

42 See https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf/methods-and-processes/procedure-manual/procedure-manual-section-1 (accessed June 6, 2023).

43 “Misinformation is false or inaccurate information—getting the facts wrong.” See https://www.apa.org/topics/journalism-facts/misinformation-disinformation (accessed May 16, 2023).

- Providing equitable access to—and coverage for—risk-based, evidence-based preventive services for individuals at high risk of developing cancer.

- Developing a comprehensive, easy-to-use database of federal and state regulations related to health care services and insurance coverage.

- Designating best practices for care coordination for individuals at high risk of developing cancer.

- Improving health literacy among the population and within health care organizations.

COMMUNICATING CANCER RISK AND PREVENTION

Clear communication is essential for disseminating information about prevention and risk reduction, said Maria Thomson, associate professor of health behavior and policy, and director of community engagement in research at the Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center. Several speakers highlighted best practices to communicate about the evidence base for cancer prevention.

Communicating the Evidence Base Effectively

Thomson noted that the COVID-19 pandemic brought to the forefront the critical need for clear communication to the public about health threats and mitigation measures. She said the lessons learned are also applicable to communication efforts for cancer prevention and risk reduction. During the pandemic, messaging about infection control measures, such as masking, vaccination, and social distancing, had to shift rapidly in response to emerging data and evolving science. Communication was also negatively affected by misaligned policies at the community, state, and federal levels, as well as confusion and mistrust fanned by misinformation campaigns. Thomson noted that some of the same structural and historical factors contributing to the disproportionate COVID-19 burden among minority communities created inequities in accessing health information and services and reinforced mistrust in public health. Anderson noted that trust is essential, and asked how it can be fostered. Thomson said that communicators and leaders need to learn from and build trustworthiness within the communities with which they are collaborating.

Thomson focused on key areas for effective communication to advance cancer policy: environmental context, alignment, and technology (see

Figure 7). Regarding the environmental context, she said it is important to acknowledge structural factors that foster mistrust. It is also important to find ways to communicate that avoid polarization. For example, in contexts where strong scientific evidence exists in support of an idea, a process, or a treatment, there can remain vocal and substantial propagation of disinformation44 that attempts to undermine it. Thomson remarked that this can happen when there is a lot of information or conflicting information. Recognizing this challenge, she suggested focusing on positive, action-oriented strategies rather than addressing arguments that actively attempt to conflate the issue with identity and beliefs (Kahan, 2015).