Communities, Climate Change, and Health Equity: Lessons Learned in Addressing Inequities in Heat-Related Climate Change Impacts: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2023)

Chapter: Communities, Climate Change, and Health Equity: Lessons Learned in Addressing Inequities in Heat-Related Climate Change Impacts: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

|

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief |

Communities, Climate Change, and Health Equity: Lessons Learned in Addressing Inequities in Heat-Related Climate Change Impacts

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

INTRODUCTION

Extreme heat is a pervasive and critical hazard of climate change. While heat poses a significant threat to large swaths of the human population, it is not affecting all people or all communities equally. To explore what it takes to prevent and mitigate inequitable health impacts from extreme heat, the National Academies’ Environmental Health Matters Initiative (EHMI) organized a workshop on June 20-21, 2023, titled Communities, Climate Change, and Health Equity: Lessons Learned in Addressing Inequities in Heat-Related Climate Change Impacts.

The workshop was the third in a series of EHMI events exploring the state of knowledge about climate-related health disparities. This hybrid event convened people with lived experience in communities affected by extreme heat; experts in environmental health, economic, and racial justice; climate scientists; energy specialists; and people involved in sustainable planning and disaster relief. Through presentations, shared stories, and interactive discussions, participants explored real-world challenges related to extreme heat, along with actions being pursued to prevent, adapt to, or mitigate the health consequences.

CONTEXT

On the first day, speakers provided context on the current state of knowledge about disparities in heat-related health impacts of climate change and their underlying drivers. They highlighted gaps of implementation in creating solutions for all, with several speakers specifically noting challenges of environmental racism, as well as the approaches being explored to address these gaps from the lenses of research, policy, and grassroots action.

Heat Action Planning to Address Urban Inequities

Vivek Shandas (Portland State University) addressed the context for strategies being employed to enhance resilience in the face of extreme heat. Earth is at a moment of massive, transformational change, he said, “unlike anything human civilizations have seen, on a scale as we have never known.” Heat is central to many climate hazards. In addition to an increasing number of extreme heat days, warming is driving changes such as sea level rise and the growing frequency of drought and wildfire. At the same time, the acceleration and concentration of human activity in dense urban areas has contributed to unprecedented prosperity but has also amplified the toll of climate-related tragedies.

“Heat is not something that everyone experiences equally,” Shandas stressed. Inequities create situations where vulnerable populations are more exposed to the danger of extreme heat and less able to protect themselves. To address this urgent and growing concern, he said that research on both extreme heat and urban inequity must be woven into policy from the local to the international levels to “help safeguard those communities who are hit first and worst.”

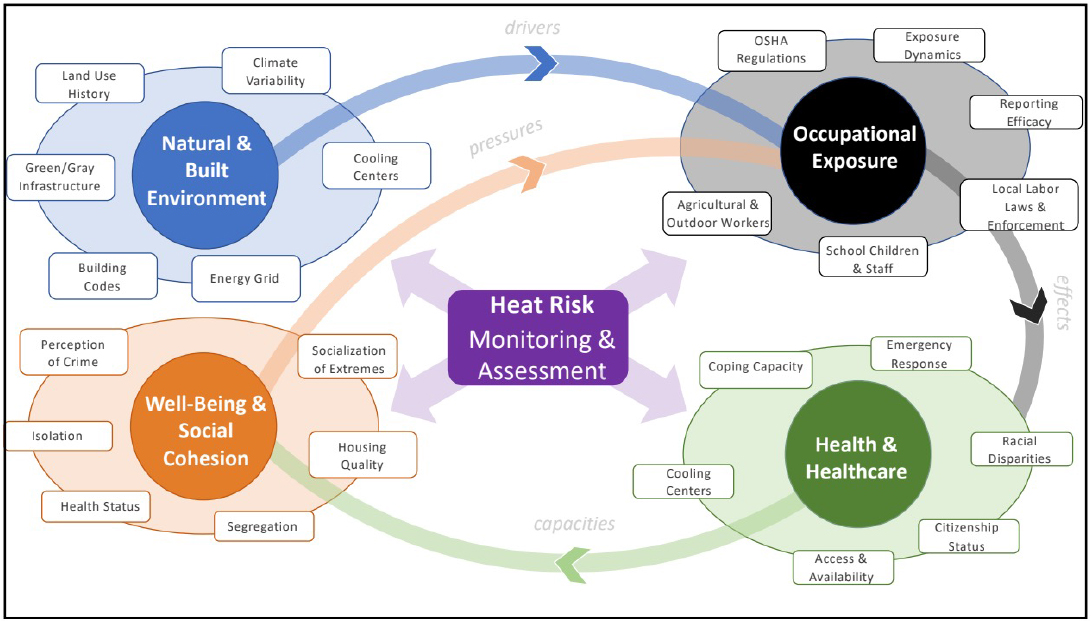

Unfortunately, Shandas said, most well-funded heat mitigation strategies are reactive rather than proactive, and many have not been adequately evaluated or assessed. To inform the design and implementation of more effective resilience mechanisms, he emphasized the need to attend to the interconnected, intersectional aspects of the natural and built environment, people’s well-being and social cohesion, occupational heat exposures, and health and healthcare (Figure 1). Incorporating multifaceted data points such as exposure probabilities, building codes, housing availability, citizenship status, health care access, and occupational safety regulations can provide crucial context on the hazards that policies could address. In particular, Shandas said it is important to elucidate the underlying drivers of community connection and resilience, without which people are more isolated and less able to respond to extreme heat. “When communities are better connected and more socially cohesive, they are better able to respond to acute pressures,” Shandas noted.

Shandas also shared that understanding the context of heat risk can inform locally relevant heat exposure mitigation strategies. For example, researchers and community-based organizations in Los Angeles mapped local green spaces to identify high-risk neighborhoods and direct resources accordingly.1 In another example, researchers considered several configurations of buildings, green space, and code modifications to identify a multi-family housing design that would produce the lowest ambient temperatures.2 Detailed data

__________________

1 “Los Angeles Urban Forest Equity Assessment Report.” Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.cityplants.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/LAUF-Equity-Assement-Report-February-2021.pdf.

2 Makido, Y., Hellman, D., & Shandas, V. (2019). Nature-Based designs to mitigate urban heat: The efficacy of green infrastructure treatments in Portland, Oregon. Atmosphere, 10(5), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10050282.

SOURCE: Adapted from Batchelder Hal, Bograd Steven J., Di Lorenzo Emanuele, Horii Toyomitsu, Kang Sukyung, Katugin Oleg N., King Jackie R., Lobanov Vyacheslav B., Makino Mitsutaku, Na Guangshui, Perry R. Ian, Qiao Fangli, Rykaczewski Ryan R., Saito Hiroaki, Therriault Thomas W., Yoo Sinjae, 2019. Developing a Social–Ecological–Environmental System Framework to Address Climate Change Impacts in the North Pacific. Frontiers in Marine Science 6.

on temperatures across a city, combined with studies of the built environment and how different cooling strategies play out at the granular level at which people live—for example, on different floors of a housing complex—can spur actions that help to reduce inequities.

Heat Exposure and Environmental Justice

Rupa Basu (California Environmental Protection Agency) discussed disparities in heat-related health impacts and opportunities to address them. Heat exposure is the leading climate-related cause of death, she noted, and heat-related deaths are on the rise worldwide.3,4 Broadly speaking, the countries responsible for the bulk of the world’s carbon emissions are spared the worst of climate change’s impacts, Basu shared, but populations that are especially vulnerable to heat exposure exist in every country.5,6 This includes older adults, young children, pregnant people, athletes, outdoors workers, people on certain medications, and anyone living with limited resources.

Recognizing the influence of environmental justice and environmental racism as a growing concern may also be an important step toward equitable access to health care and safe housing, as historical redlining practices and other structural inequities have forced marginalized groups to live near areas that tend to become heat islands, such as power plants and highway interchanges. This is exacerbated by poverty and minority status, which can create barriers to healthcare access, which in turn lead to poorer health outcomes.

Although heat is widely understood to pose a serious public health threat, tallies of heat-related illnesses and deaths are often unreliable. Basu pointed to several reasons for this discrepancy: there is no official definition of a heat wave; heat advisories are used inconsistently; individuals and groups respond differently to extreme heat; and some health outcomes, including cardiovascular problems, respiratory diseases, adverse birth outcomes, and mental health crises, are exacerbated by extreme heat but seldom connected to heat exposure in official records.

Many people vulnerable to extreme heat are unaware of their risk. However, heat deaths may be preventable through individual actions and policy changes at the local, state, and federal levels. Basu suggested that public health campaigns are needed to increase awareness in communities and among decision-makers by sharing findings from epidemiological studies at conferences and in journals with governments and non-profit agencies, in publications directed at healthcare workers, and with the general public. Finally, she said there is an urgent need to identify and invest in sustainable, community-level interventions that do not increase fossil-fuel dependency to address the cumulative impacts of multiple crises and chronic problems on high-risk populations. “We’ve already done enough of identifying vulnerable populations,” Basu said. “We know who they are, we know where they live, and it’s time to […] take action.”

Integrating Heat Research and Practice

Phoenix, Arizona has seen some of the most prolonged and severe heat waves of any large U.S. city. David Hondula (Arizona State University and the City of Phoenix) highlighted how the city’s response offers context on what cities can do to mitigate heat risks and the role of research in informing these efforts.

Hondula noted that people are becoming increasingly aware that extreme heat—a multifaceted problem at the intersection of urban climate dynamics and environmental, social, and technological justice—is a significant public health risk. In Phoenix, this awareness has spread beyond the public health and research spheres to reach the general public and the city’s decision-makers, thanks in part to influential media campaigns drawing attention to people who have died from heat-related causes, better documentation of the increasing rates of heat-related deaths, and

__________________

3 “Heatwave Deaths: 760 Lives Claimed by Hot Weather as High Temperatures Continue.” n.d. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/weather/10187140/Heatwave-deaths-760-lives-claimed-by-hot-weather-as-high-temperatures-continue.html.

4 “India Heat Wave Kills More Than 2,300 as Monsoon Is Delayed | Time.” n.d. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://time.com/3904590/india-heatwave-monsoon-delayed-weather-climate-change/.

5 United Nations. (n.d.). On the Frontline of Climate Crisis, Worlds Most Vulnerable Nations Suffer Disproportionately. UN. https://www.un.org/ohrlls/news/frontline-climate-crisis-worlds-most-vulnerable-nations-suffer-disproportionately.

6 IPCC. (2023). Summary for policymakers. In Cambridge University Press eBooks (pp. 3–34). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.001.

grassroots capacity-building coalitions to address heat hazards.7,8,9 One outcome is the establishment of a new municipal office focused on heat response and mitigation.

As also highlighted by Basu, heat is a critical environmental justice issue. Neighborhoods with less shade and vegetation see higher rates of heat-related illness, and the challenges of living in a more heat-stressed environment can have long-term effects on individuals and communities.10 Although large-scale disparities in urban environments may seem intractable, research points to actions that cities can take to reduce ambient temperatures and design cooler cities.11 “Actions that cities can take can produce cities of the future that are cooler than the ones we have today, even as global warming continues,” Hondula said. “That’s been a very powerful message for our local elected officials here—that cities can really make a difference in shaping the environment for their residents.”

Hondula described several considerations for guiding action. First, he emphasized the importance of identifying clear, community-defined goals and using reliable health data for precise risk measurements. In addition, he said that researchers should work collaboratively with city officials to design, implement, and evaluate heat mitigation strategies, such as tree plantings, shading structures for playgrounds, cool pavement treatments, and public cooling and hydration centers, that are tailored to the nuances of specific on-the-ground conditions and community needs.12 Finally, he said it is useful to take a portfolio management approach to determine how to optimally direct resources, who should implement each action, and who will benefit most.

A critical knowledge gap, Hondula said, is in capturing the number of heat-associated deaths and illnesses, as well as estimations of what the collective impact of interventions would be. While heat can be a minor inconvenience or a manageable problem for some, it can be a catastrophe for others. Considering this, Hondula stressed the need to measure the threats posed by extreme heat and then align local investments to the risks different groups face.13,14

Community-driven Action on Heat and Health Equity

Sonal Jessel (WE ACT for Environmental Justice) and Vernon Walker (Tufts University and Communities Responding to Extreme Weather [CREW]) discussed grassroots efforts to address inequities in the impacts of extreme heat at the community level.

WE ACT began in 1988 as a protest against a proposed sewage treatment facility in West Harlem, a neighborhood long subjected to both structural and environmental racism. Today, WE ACT continues to fight for environmental justice, embodying the idea that everyone deserves to live, work, and play in a healthy environment.

Like most big cities, much of New York becomes a heat island in the summer, and the city is seeing heat waves increasing in severity, frequency, and duration.15 Certain groups, however, are even more vulnerable to extreme heat. Jessel said these groups often live in older, crowded, poorly maintained apartment buildings; their neighborhoods have fewer trees, less green space, and more pollution; and they are more likely to have

__________________

7 “The Human Cost of Heat | AZ Central.” n.d. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://static.azcentral.com/human-cost-heat/.

8 Putnam, Hana, David M. Hondula, Aleš Urban, Vjollca Berisha, Paul Iñiguez, and Matthew Roach. 2018. “It’s Not the Heat, It’s the Vulnerability: Attribution of the 2016 Spike in Heat-Associated Deaths in Maricopa County, Arizona.” Environmental Research Letters 13 (9): 094022. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aadb44.

9 “Phoenix Urban Heat Leadership Academy.” n.d. Accessed July 26, 2023. http://phxrevitalization.org/ccs/thenaturesconservancy/leadershipacademy/index.htm.

10 Jenerette, G. Darrel, Sharon L. Harlan, Alexander Buyantuev, William L. Stefanov, Juan Declet-Barreto, Benjamin L. Ruddell, Soe Win Myint, Shai Kaplan, and Xiaoxiao Li. 2016. “Micro-Scale Urban Surface Temperatures Are Related to Land-Cover Features and Residential Heat Related Health Impacts in Phoenix, AZ USA.” Landscape Ecology 31 (4): 745–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0284-3.

11 Georgescu, Matei, Philip E. Morefield, Britta G. Bierwagen, and Christopher P. Weaver. 2014. “Urban Adaptation Can Roll Back Warming of Emerging Megapolitan Regions.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (8): 2909–14.

12 Schneider, Florian A., Johny Cordova Ortiz, Jennifer K. Vanos, David J. Sailor, and Ariane Middel. 2023. “Evidence-Based Guidance on Reflective Pavement for Urban Heat Mitigation in Arizona.” Nature Communications 14 (1): 1467. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36972-5.

13 Keith, Ladd, Sara Meerow, David M. Hondula, V. Kelly Turner, and James C. Arnott. 2021. “Deploy Heat Officers, Policies and Metrics.” Nature 598 (7879): 29–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02677-2.

14 Guardaro, M., D. M. Hondula, J. Ortiz, and C. L. Redman. 2022. “Adaptive Capacity to Extreme Urban Heat: The Dynamics of Differing Narratives.” Climate Risk Management 35 (January): 100415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2022.100415.

15 Krause, Kea. 2019. “How NYC Is Protecting People from the Deadliest Disaster.” Grist. August 13, 2019. https://grist.org/Array/how-nyc-is-protecting-people-from-the-deadliest-natural-disaster-heat/.

difficulty paying for food or rent. They are also more likely to experience poverty, food and energy insecurity, chronic health problems, and historical and structural racism, which amplifies heat risks and other health risks. “If you’re having an issue with extreme heat,” Jessel noted, “you’re probably having an issue with a bunch of other things, too.”

Addressing the risks of extreme heat can save lives. WE ACT identifies local-scale factors and policies that lead to extreme heat risks and proposes changes to protect and invest in the most vulnerable populations. Among other measures, the organization works to undo environmental racism on the policy level and advocates for city-wide emissions reductions, enhanced tree canopy, shaded playgrounds, green space expansions and maintenance, practical and accessible cooling centers, access to and funding for improved indoor cooling solutions, and alerts to raise awareness of heat risks.16 Jessel reiterated the need for sustainable interventions that do not increase the reliance on fossil fuels or favor short-term gains over long-term solutions.

Walker noted that heat is the leading weather killer across the country, yet is often underestimated and underappreciated.17 “Extreme heat is deadly, dangerous, and disastrous,” he said. As temperatures rise, it is becoming unhealthy to be outside for most summer days, even in northern areas of the United States. As Jessel described in New York, in New England it is common for communities living in or near heat islands to have a history of environmental injustice. Underserved communities have a lot of needs; however, and for many, climate issues may be seen as less urgent than racial and economic justice issues. Against this backdrop, CREW—a grassroots organization dedicated to building equitable, inclusive neighborhood climate resilience through education, service, and planning—attempts to tie all the threads together to elucidate the relationships between public health, climate change, and social justice.

To help neighborhoods prepare for and respond to extreme heat, CREW established climate resilience hubs across the United States in partnership with community-anchoring institutions like libraries, churches, and community centers. These hubs hold public workshops on minimizing risks from heat waves and other natural disasters, and distribute tangible resources, such as air conditioners and mobile cooling kits. To address the cumulative health risks from heat exposure, CREW partners with hospitals, nature centers, food services, and fitness organizations to teach workers to recognize and treat extreme heat exposure. At a policy level, CREW also advocates for legislation to promote heat resilience and improve access to heat mitigation measures.

SHARING STORIES

Over the course of the workshop, five speakers shared stories highlighting ways organizations have navigated external expectations, policies, resource limitations, and available tools in tackling community needs around extreme heat. These on-the-ground localized experiences shed light on opportunities to form scalable and impactful partnerships to co-create solutions to extreme heat.

Enhancing Clinical Preparedness

Cecilia Sorensen (Columbia University) described lessons from the 2021 heat wave in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, a heat event that took a devastating toll on affected communities but catalyzed a “never again” moment for the region’s local governments, healthcare facilities, and other institutions. As a result, many places in the region now have heat action coordination plans to help them avoid repeating some of the shortcomings that contributed to the event’s impacts and disparities. Community-level strategies to prevent heat-related deaths can include public awareness campaigns to inform people about heat vulnerabilities and adaptations, along with better coordination among healthcare workers, social workers, case managers, meteorologists, and pharmacists. Examples of key actions for hospitals, as shared by Sorensen, include conducting heat hazard vulnerability assessments; providing appropriate training and communication mechanisms for clinicians and emergency responders; and stockpiling supplies

__________________

16 “WE ACT for Environmental Justice 2023 Policy Agenda.” n.d. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.weact.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2023-Policy-Agenda.pdf.

17 US Department of Commerce, NOAA. n.d. “Weather Related Fatality and Injury Statistics.” NOAA’s National Weather Service. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.weather.gov/hazstat/.

for handling heat-related illness, including ice, cold fluids, fans, core temperature monitors, and cold-water immersion equipment.18

While such steps should be locally relevant, Sorensen said, places need not wait to suffer the impacts of a severe heat wave before taking action. “No place in the U.S. should be taken off guard by the risks of climate change,” she stated. She also added that, as a source of trusted information for many individuals, healthcare professionals could do a better job of routinely incorporating heat safety education into their practice by providing clear information and advice for dealing with extreme heat.

Addressing Workplace Heat Hazards

Jora Trang (Worksafe, Inc.) shared the stories of two legal developments in California that have helped improve workplace safety in the face of extreme heat. California’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA) instituted the nation’s first outdoor heat employment standard after a young farm worker died from heat exposure. That standard has been a successful instrument for protecting outdoor workers but does not apply to those who work indoors. This represents an important gap, especially since indoor environments, such as warehouses and metal shipping containers, can become hotter than the ambient outdoor air, Trang noted. After a worker collapsed due to heat in one such environment, Cal/OSHA won the right to create an indoor heat standard. In both cases, Worksafe, Inc. was instrumental in bringing worker advocates, employers, legal experts, and policymakers together to galvanize attention to the issue of workplace heat exposure and spur action.

Some employers have resisted regulations on the premise that they can effectively manage risks independently without mandates, but Trang said that experience shows that laws are necessary to ensure basic worker protection. Multiple cases have been documented in which workers were denied breaks, could not physically get to water coolers, or could get to water but lacked cups, for example. “If I don’t mandate you to provide cups and water and a place to cool down, you won’t,” she stated. She also noted that appealing to more shared, less politically charged values, such as quality of life and job quality, can also help to build public support for efforts to encourage employers to improve worker safety.

Community-based Data Collection

Zelalem Adefris (Catalyst Miami) highlighted examples of community-based heat action in Miami, Florida. Community Leadership on the Environment, Advocacy, and Resilience is a program that empowers community members to advocate for and respond to climate threats faced by residents in Miami-Dade County. Although Miami has seen a marked increase in the number of high-heat days, the Miami Health Department has not historically collected data on health impacts from extreme heat, leading to a dearth of knowledge and awareness of the health risks. To fill the gap, Catalyst Miami organized a community-based effort to collect data on the temperatures being experienced on the ground.

The results revealed that the official temperatures, typically taken at airports with sensors placed 10-20 feet off the ground, failed to capture the heat island effect people experience in different parts of the city.19 Increased attention to extreme heat threats has led to the appointment of Miami’s first heat officer, a lowering of the threshold for issuing heat warnings, and the initiation of a community-driven heat action plan to provide material relief during heat events.

Participatory Science for Resilience

Dana Habeeb (Indiana University) described Beat the Heat, a program being implemented in two Indiana towns that helps communities develop targeted heat response plans. One unique aspect of the program is the inclusion of a heat officer who convened a task force made up of communities and government decision-

__________________

18 Patel, Lisa, Kathryn C. Conlon, Cecilia Sorensen, Samia McEachin, Kari Nadeau, Khyati Kakkad, and Kenneth W. Kizer. 2022. “Climate Change and Extreme Heat Events: How Health Systems Should Prepare.” NEJM Catalyst 3 (7): CAT.21.0454. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.21.0454.

19 Clement, A. C., Troxler, T. G., Keefe, O. R., Arcodia, M., Cruz, M., Hernandez, A., Moanga, D., Adefris, Z., Brown, N. J., & Jacobson, S. (2023). Hyperlocal observations reveal persistent extreme urban heat in southeast Florida. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. https://doi.org/10.1175/jamc-d-22-0165.1

makers to provide support and guidance for program coordinators.

To assess community needs and priorities, researchers conducted surveys and focus groups to gauge understanding of extreme heat risk and adaptive capacities among residents and local government personnel. This process revealed several common barriers to heat adaptation, including the cost of running and maintaining home cooling systems; mobility challenges for older people on hot days; limited awareness of heat-related health risks among younger people; and barriers to cross-organizational collaboration in government.

Community members also took part in a participatory science project that uses bike- and car-mounted sensors to capture hyper-local data, and researchers created a sensitivity score based on a combination of social and demographic factors.

Data generated through these approaches are being incorporated into community education and engagement efforts, leveraged to identify the areas and groups most vulnerable to heat, and apply for grants to support interventions such as planting trees. Having completed the community assessment stage, program organizers now focus on developing heat management strategies and heat wave response protocols for both communities.

Planting Trees for Equity

Raed Mansour (Chicago Department of Public Health) described Our Roots: Chicago, a $46 million, 5-year program to improve Chicago’s urban canopy cover by planting around 75,000 trees. To identify priority areas for tree plantings, researchers combine social, economic, environmental, and public health data and engage communities to understand their priorities and address the injustices that have led to low-canopy communities.

The Community Tree Equity Working Group is a primary mechanism for community involvement. By meeting monthly, this group of more than 135 members helps ensure that community organizations, researchers, and government officials come together regularly. Although the group agrees on its mission, Mansour noted that members do disagree about specifics. This makes it important for participants to focus on learning from each other and listening to each other. In addition, the project uses a ‘train the trainer’ model to create tree ambassadors who engage with neighbors to inform them about tree plantings and shape the character of their own neighborhood.

OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTING HEAT SOLUTIONS

A number of well-known solutions can help prevent heat-related illness and death, yet each heat wave brings a heavy human toll. In a series of panel discussions and breakout groups, the workshop’s first day brought to the forefront several challenges related to extreme heat and implementing heat mitigation solutions. To identify examples of opportunities to overcome those challenges, the second day of the workshop was designed to facilitate collaborative solution-oriented discussions.

Seven panelists representing government, academia, industry, and community perspectives—Rupa Basu, Nikki Cooley (Northern Arizona University), Jane Gilbert (Miami-Dade County), Garry Harris (Center for Sustainable Communities), Hunter Jones (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), Jessica Tredinnick (3M), and Vivek Shandas—discussed their responses to the key challenges and barriers discussed in the breakout sessions on the first day, as summarized in the different sections below. This process allowed panelists and moderators to explore innovative, integrated solutions that align with the needs of different sectors. To further enrich the discussion, audience members also submitted solutions for consideration via an online tool.

Over the course of this collaborative discussion, participants examined key barriers in the context of natural and built environments, workplaces, healthcare, well-being, and social cohesion. The solutions shared covered many interconnected aspects of extreme heat preparedness, response, and resilience. Areas of particular emphasis included opportunities to develop holistic cross-sectoral solutions; strategies to fund and implement improvements in the built environment; suggestions for improving the collection, translation, and distribution of heat-related data; and the role of

meaningful community engagement in guiding solutions, including through leveraging local knowledge and expertise. The views shared in the next sections are by individual or several participants of the workshop but do not constitute a consensus.

Natural and Built Environments

Several participants shared that cooling centers and evacuation facilities are a critical aspect of the built environment that can save lives during periods of extreme heat. They noted the importance of adequate funding to create cooling centers with enough backup power to handle power outages; however, some noted that it has proven difficult to get funding for this from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Cooling centers based in buildings used as libraries and movie theaters work well in urban areas because of accessibility, but many participants noted that this solution does not work well for rural communities. One potential solution is to move cooling centers out of government control and allow communities to control and maintain them.

Focusing on the people who use cooling centers, rather than the buildings themselves, might also enhance efforts to address issues that drive people to cooling centers in the first place. Several participants noted that it is important not only to provide cooling centers and shelters but also to make them safe and accessible, especially for overnight shelters, such as by providing transportation. Finally, some participants suggested that creative approaches could be used to explore how “old” infrastructure or strategies might be applied to new situations. For example, well-insulated vacant office buildings could be converted into cooling centers, or, as Nikki Cooley explained, new facilities could be built using indigenous approaches to cooling, such as utilizing local materials and taking advantage of tree cover for shading.

Many heat-related deaths occur inside and at home, highlighting the importance of preventing and addressing dangerous levels of indoor heat.20 Barriers to cooling solutions at the individual level include homes with poor insulation, old or outdated infrastructure, non-optimal building codes that do not include a minimum cooling standard, and lack of access to funds to make energy-efficient upgrades, several participants said. In addition to buildings that lack air conditioning altogether, homes with only a single window air-conditioning unit are vulnerable because that unit could easily break.

Several panelists noted that many cities do not measure heat resilience and therefore have an incomplete view of the gaps that lead to heat vulnerability. Some participants suggested that creating a place where people can report extreme indoor heat could help, as could programs promoting healthy homes, weatherization, and insulation improvements. For home upgrades, a few participants suggested that providing up-front funds to support steps to upgrade homes could likely be more impactful among low-income communities than providing reimbursements, a model that requires people to cover up-front costs themselves. Since the barriers can be amplified for renters, who often rely on their landlords to implement necessary upgrades, several participants stressed that solutions that involve public-private partnerships could attend to the needs of renters in addition to homeowners.

Several participants pointed to the benefits of more discussions around housing and heat risk across multiple levels of government, from local departments all the way up to federal housing programs. There are proven practices and existing guidance that could be tapped into, but some suggested that mandates—such as a maximum temperature threshold for housing—may be needed to translate guidance into meaningful action, such as through provisions for green or white roofs, energy efficiency requirements, and in-home temperature and humidity sensors.

As several participants noted, the design of buildings, public spaces, and infrastructure, such as bus stops, can have a major impact on heat experienced on the ground in communities. To better leverage greenspace and landscaping solutions, some participants stressed the importance of working with nature, instead of against it. For example, smart surfaces, cool roofs, porous pavement, and tiny urban forests can be used

__________________

20 Snow, A. (2023, May 1). Deadly heat waves threaten older people as summer nears. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/climate-aging-heat-deaths-f95f3567fe9fa97c03c59bdfe839e202.

to manage sun and rain more efficiently in urban areas. In addition, several participants suggested departments of transportation, zoning committees, and community groups could work together to identify public infrastructure that poses heat concerns and develop solutions.

Many participants also pointed out that eliminating fossil fuels is a core part of risk reduction. Microgrids that incorporate solar, wind, or geothermal technologies to generate and store power can enhance resilience both to supply everyday power and to keep cooling centers, libraries, and community centers running during extreme heat events. Given the constraints in the current regulatory environment, some participants noted that it would be key to engage local representatives on rule changes to support such approaches.

Environmental barriers to planning and implementing heat resilience measures are often tied in with pervasive social inequities. Some participants noted that ageism, ableism, poverty, rural inequities, political polarization, uneven attention to demographic and geographic diversity, and historical and present racist practices can create and exacerbate barriers. In addition, particular groups, including people who are unhoused and those who are incarcerated, are frequently underserved in heat planning.

Several participants stressed that many environmental barriers can be overcome through dedicated funding, an emphasis on accessibility, and public awareness campaigns to convey the dangers of extreme heat and encourage both the public and policymakers to take risks seriously. Addressing barriers also likely benefits from close multidisciplinary collaboration; authentic community engagement and strong public communication; clearly defined goals and appropriate metrics; effective data collection; long-term planning; nature-based solutions; and novel, unique, or adaptable strategies to address risks with a climate justice lens.

Workers and Economic Productivity

Some participants shared that providing access to shade, water, breaks, and other cooling measures can reduce heat-related hazards and even increase productivity in the workplace. However, they said the implementation of such measures is undermined by information gaps among employers, health and safety professionals, and workers regarding the perils of heat and ways to address them. For example, many employers do not appreciate that they will ultimately save money by protecting their workers from heat, many industrial hygienists have not been adequately trained on heat hazards, and many workers are not aware of the workplace rights they have. Mental health is another important consideration. Studies have shown that suicides and homicides increase when temperatures increase, but high-risk populations, such as outdoor workers, are often overlooked.21,22

Even when workers and employers understand the health harms of heat, they may not have the tools to address them, some panelists shared. Small business owners may not have the staff, technological expertise, economic resources, or incentives to develop a robust heat emergency plan. The agricultural sector raises some particular complications. One is that employers often offer housing, blurring the line between home and occupational heat exposure. In addition, many farming jobs are seasonal and time-sensitive, which often creates pressure to work continuously for long hours despite dangerous conditions.

Some participants also noted that workers are often blocked or discouraged from organizing to demand protection. In addition to facing economic and social disadvantages, many workers are afraid to call attention to their situations, however dangerous, because of the risk of retaliation. These fears come from the institutional, structural, and economic forces that put workers—especially low-wage workers and workers of color—in harm’s way, many participants noted. Factors contributing to these disadvantages can include ageism, ableism, pregnancy discrimination, language barriers, economic and racial inequalities, and immigration

__________________

21 Burke, M., González, F., Baylis, P., Heft-Neal, S., Baysan, C., Basu, S., & Hsiang, S. (2018). Higher temperatures increase suicide rates in the United States and Mexico. Nature Climate Change, 8(8), 723–729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0222-x.

22 Johnson, A. (2023, July 6). Here’s Why Warm Weather Causes More Violent Crimes—From Mass Shootings To Aggravated Assault. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ariannajohnson/2023/07/06/heres-why-warm-weather-causes-more-violent-crimes-from-mass-shootings-to-aggravated-assault/?

policies. In addition, healthcare costs and competing priorities can pose barriers to better worker protection.

Regulatory frameworks, guidelines, and best practices can be crucial tools to address workplace heat exposure, many participants said. California’s laws in this area provide one example that others could follow, but federal-level regulation that specifies and requires specific programmatic elements may be useful. Developing OSHA heat safety rules, along with increased funding for inspections and enforcement, could help to improve on-the-ground conditions for workers, “who should be seen as relatives, not just workers,” as shared by Cooley.

Finally, several participants emphasized the role of effective communication in advancing heat resilience solutions in workplaces. It is important for heat-related information campaigns to be provided in workers’ native language(s) and in various forms, such as posters, social media, and radio shows. It also helps to get employees involved in such campaigns. Implementing precautions in the form of everyday practices rather than focusing only on education is also important. For example, this could involve noting where workers spend time and taking actions in those locations, such as adding canopy shades and coolers, along with instituting regular breaks. In terms of educating leadership, a few participants emphasized the value of helping leaders understand and see themselves what it is like to be a worker so that they can more fully appreciate their needs.

Health and Healthcare Systems

An example of one key issue in health and healthcare is the existence of silos in terms of where knowledge is, who is included in conversations, and who has access to healthcare, several participants shared. Health is multifaceted because it encompasses mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional health and is also tightly connected to the health of the environment in which people live. There are often silos and barriers that hinder communication among clinicians, emergency responders, specialists in occupational and environmental medicine, epidemiologists, health departments, community organizations, traditional healers, and others, who all have different (and valuable) perspectives on an extreme heat crisis. Some participants pointed to opportunities to recognize and learn from other knowledge systems, including legitimizing indigenous knowledge, that incorporate holistic views, relationships, and collaboration to address health.

Currently, responses to heat emergencies by health systems are reactive, and often the solutions are outside of the health system. A few participants expressed the goal to be more proactive, for example, by developing heat emergency plans and bolstering equipment to handle power outages and large influxes of heat-related illnesses; incorporating spatially granular, timely data on heat and health; and talking to patients about hot days planning. However, practitioners are not always connected to community organizations that could help with these efforts. In addition, many healthcare interventions lag behind the accelerated pace of environmental issues. It is clear that climate change impacts are happening now, and it is important to plan for future heat emergencies with appropriate planning and infrastructure.

Some participants emphasized the benefits of more education and training for doctors and nurses so that these practitioners can recognize who is at risk and understand how heat can affect people on certain medications or with chronic conditions. In addition, clinicians may be well positioned to play a bigger role in sharing resources that can help address the root causes of patients’ heat exposure and help keep them out of the clinic or hospital, for example, by providing information on utility assistance programs or helping workers understand their rights around taking breaks. Partnerships between schools of public health and schools of medicine could help with this, several participants noted.

Finally, many participants underscored the importance of greater knowledge sharing and enhanced public health messaging around heat advisories, especially for vulnerable populations. Many participants said it is important to help both healthcare practitioners and the public appreciate heat-related illness and extreme heat

events as true emergencies in the same vein as other events such as hurricanes and floods.

Well-being and Social Cohesion

Throughout the panel discussion, several participants pointed that people who are most vulnerable to the impacts of extreme heat are often those with the least power and resources in society.23 Discrimination in various aspects of life can lead to an increased risk of extreme heat exposure, but there may be little political will to address this among policy- and decision-makers. Some participants suggested that better and more consistent reporting of heat-related health impacts could help draw attention to the human toll and the urgent need for interventions, especially for often marginalized groups such as immigrants, older people, people with disabilities, and rural populations.

While there may be actions that individuals can take to reduce their risks in the face of dangerous heat, many participants stressed that solutions at the community, environmental, and policy levels may be beneficial to achieve broader impacts. Similarly, some participants noted that heat is not a single, isolated issue but one that is connected with, and compounded by, other climate hazards and challenges, pointing to the importance of a systems approach. For example, focusing on technology alone (like installing air conditioners) may not sustainably address the problem if people are not able to afford the electricity needed to use them. Access to information is also vital, and many participants emphasized the importance of culturally relevant communication from trusted and credible sources about heat risks that can effectively reach the most vulnerable populations.

There is often a perception that managing heat risk comes down to individual responsibility. However, staying cool often requires being able to afford air conditioning, having a car, or being able to travel, all of which may be out of reach for people with low resources. The focus could shift away from individuals by using messaging that encourages people to check on others, such as neighbors, or make sure those within their care are drinking enough water.

Education and Community Collaboration

There is a great deal of guidance on how to plan and design interventions to mitigate heat, but some participants pointed out that it can be difficult to translate this into action in a way that truly helps vulnerable people and communities. When working with rural, Indigenous, and historically marginalized communities, it is important to hear their perspectives. This does not mean just circulating surveys and handing out flyers, but getting to know the community, several participants said. One communication strategy that was repeatedly raised during workshop discussions is the importance of stories, which many participants said are most impactful when communicated in a language and manner that people intuitively understand and can relate to their own lives.

Empowering communities to build capacity and create their own solutions is a key example of future work. An example shared by a panelist is the train-the-trainer models, which can be a good way to engage community members and leaders in sharing and circulating information and resources, to amplify the number of people reached. Another way to engage communities is to offer technical and planning support, and provide funding for an online clearinghouse for local efforts, to scale successful but isolated programs. This could create an information flow between communities and various governance levels. For example, creating places for communities to share their success stories could inspire other communities to implement similar solutions. This could also include reporting apps or tools that might be housed by a government body but could be co-developed with community members, who understand what is important to share.

Participatory science was discussed as another potential solution that could help address silos. This could include social science surveys, conversations with community members, and involving them in data collection, among other approaches.

__________________

23 EPA. (2023, August 3). Heat Islands and Equity. US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/heatislands/heat-islands-and-equity.

In terms of education and training, some participants noted that programming that promotes social cohesion or reduces other types of risks can often simultaneously help reduce risk from heat. Shandas said that there is ample evidence in the literature on natural hazards that shows that better connected communities are better able to respond to acute pressures from heat or other events. However, one primary barrier to implementing programming on mitigating heat risks is the lack of effective training on how to best accomplish this. For example, a few participants suggested that healthcare workers would likely benefit from better training on how to identify and report heat-related health impacts, and for teachers or caregivers on how to balance the need for exercise with the need to stay cool. More work can also be conducted to communicate in a culturally inclusive way or develop programming that adequately incorporates non-institutional or local knowledge and expertise, many participants noted. A potential communication solution is to have conversations based on trust, and use the insights gained to create education campaigns about heat and facilitate community-building or “placemaking” more broadly.

REFLECTIONS

The two-day workshop surfaced many pervasive barriers in addressing inequities in the health impacts of extreme heat, but also highlighted many forward-looking solutions, stories of success, and the importance of keeping momentum to go deeper in our collective thinking. Overall, several participants emphasized the importance of building trust and taking an inclusive approach, engaging with and empowering communities, and proactively developing and implementing heat mitigation solutions across multiple sectors beyond emergency response.

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was prepared by Anne Johnson, Audrey Thévenon, and Sabina Vadnais as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The statements made are those of the rapporteurs or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

WORKSHOP PLANNING COMMITTEE MEMBERS Anna C. Gunz (Co-Chair), Children’s Hospital, London Health Sciences Center and Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry; Sabrina McCormick (Co-Chair), Aclara Advanced Materials; Mikhail V. Chester, Arizona State University; Juanita M. Constible, Natural Resources Defense Council; Alison Frazzini, Los Angeles County; Daniel E. Horton, Northwestern University; Carlos E. Martín, Brookings Institution and Harvard University; Nambi J. Ndugga, Kaiser Family Foundation; Cecilia Sorensen, Columbia University.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Juanita M. Constible, Natural Resources Defense Council, Jeremy Hoffman, Groundwork USA, and Jane Gilbert, Miami-Dade County. Lauren Everett, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS This workshop was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2023. Communities, Climate Change, and Health Equity: Lessons Learned in Addressing Inequities in Heat-Related Climate Change Impacts: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press: https://doi.org/10.17226/27204

|

Division on Earth and Life Studies Copyright 2023 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|