A Population Health Workforce to Meet 21st Century Challenges and Opportunities: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Context-Setting Perspectives on Workforce History and Law

Lauren Smith, chief health equity and strategy officer at the CDC Foundation noted the timeliness of the upcoming conversation on workforce, and asked how the field might emerge from the pandemic as something new and increasingly successful.

Smith highlighted multiple intertwined crises in the public health workforce: burnout and fatigue from 2 years of confronting a pandemic that has overtaken other public health priorities; weariness, frustration, and lack of trust and support, to hostility that has caused many practitioners to leave their jobs; and a potential mismatch between the experience and skills of the workforce and the responsibilities that are needed to overcome new and persistent challenges. Examples include the “insidious and seemingly expanding mis- and dis-information” about topic areas such as vaccinations, pandemic, and meaningfully engaging with the public despite high levels of distrust in public health science officials.

In focusing on the past, present, and future of the public health workforce, Smith said, the panel would outline actionable steps and strive for a session that confronts the current situation with “clarity, sense of purpose, and steely resolve rather than ‘doom and gloom.’”

Smith introduced five panelists: Merlin Chowkwanyun, Donald H. Gemson Assistant Professor of Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; Shauneequa Owusu, chief strategy officer at ChangeLab Solutions and Becky Johnson, managing director at ChangeLab; Kyle Bernstein, chief of the Population Health Workforce Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); and Joshua Sharfstein, vice dean for public health practice and community engagement at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

HISTORY AND DEFINING BOUNDARIES OF PUBLIC HEALTH

Merlin Chowkwanyun gave his presentation on the history of public health and current issues surrounding population health. He began by referring to the traditional conception of the term “public health” and its relationship to society. He divided his presentation into what he referred to as “episodes” to guide the audience through his presentation. Episode 1 was an illustration of early public health’s guiding assumptions. For example, in the Early Victorian Era (1839–1850s), persons of lower socioeconomic status were sent to live in “poorhouses,” where the impoverished were forced to work to receive minimal sustenance, such as food and shelter. Chowkwanyun described poorhouses as institutions where living conditions were unsanitary and overcrowded, and many got sick and died in elevated numbers. Physicians and social reformers were tasked with discovering what the root causes of these deaths were. Chowkwanyun highlighted one physician in particular, William Farr, who worked to document the reasons behind nearly 150,000 deaths in poorhouses. For one sub-set of deaths, Farr ascribed starvation as a cause. Chowkwanyun also highlighted the works of Edwin Chadwick, a policymaker well known for work on city infrastructure, sewage, clean water, and other sanitary innovation, who later served as commissioner of the General Board of Public Health in 1848. Chowkwanyun asked “What should public health encompass?” and “How social is public health allowed to be?” To answer these questions, Chowkwanyun highlighted the General Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, an inquiry led by Chadwick and published in 1842. This report is often considered to be a founding document of the “sanitarian” school of public health. Chowkwanyun remarked that “sanitarianism,” at its most basic, is the removal of “filth and waste.” According to Chowkwanyun, the report is important because although it prompted the development of sanitary infrastructure, it played a role in “sidelining social structure.” Chadwick’s beliefs provided a circumscribed vision of public health—poverty, starvation, and other social conditions were largely off the table. Sanitary infrastructure, garbage pickup, and “getting rid of filth” were what public health should be about.

Chowkwanyun’s Episode 2 focused on the works of Robert Koch, who was a prominent figure in public health, and who is commonly said to have catalyzed “germ theory” and the “bacteriological revolution.” Chowkwanyun explained that in the Victorian era, the language of pathogens and transmissible germs that we take for granted in modern day was quite theoretical. For example, people had ways of avoiding illness by “stay[ing] away from stuff that smells bad” or “get[ting] away from the filth and the dirt.” Koch famously argued that there was an association between having pathogens in one’s body and disease. Chowkwanyun

emphasized how Koch’s work led to a view of public health in which the goal was to find viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens. This has evolved to the effort to identify genes and developing therapeutics, medicines, antivirals, antibiotics, and vaccines in modern times. But Chowkwanyun then posed the question “How reductionist or holistic should public health be?” He added that a more reductionist view focused on transmissible pathogens is not automatically the least desirable one. For example, the COVID-19 vaccine that was administered to the general population has now allowed people to resume pre-pandemic activities. Yet, at the same time, “Public health too often constricts itself to a finite list of functions.” He then added: “We have to go beyond, which raises question ‘Who is in the population workforce?’”

LAW AND POLICY SOLUTIONS FOR THE POPULATION HEALTH WORKFORCE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Becky Johnson echoed Chowkwanyun’s remarks and stated that ChangeLab takes a “holistic approach to the workforce” adding that her organization has worked to strengthen the capacity of the public health workforce for more than 25 years to “build healthier communities for all through equitable laws and policies”; ChangeLab defines the population health workforce broadly to include many professions that often do not have health in their title, she said. These partners include all government agencies and policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels, including all 3,000 health departments, and entities such as community-based organizations, health care systems, and academic institutions. Johnson then explained that her presentation would focus on context, workforce capacity needs, workforce structural needs, and centering the community around these themes.

Regarding context, Johnson said that the general public health workforce should support all professions across individual career pathways and communities by contributing to law and policy change to advance health equity. Johnson emphasized that public health is at an inflection point where its practitioners are trying to navigate how best to serve communities in the face of such challenges as rollbacks in public health authority and mistrust. Johnson proposed that supporting the population health workforce include developing strategies for navigating these ongoing challenges.

Regarding capacity, Johnson emphasized that regardless of where they are situated, practitioners must have a basic understanding of law and policy because law is critical to public health practice. For example, unjust laws and policies past and present contribute to growing health inequities and multi-generational harm, and understanding and acknowl-

edging the role of law and policy on health is essential to redressing structural discrimination and achieving health equity, Johnson said. She gave the example of an asthma researcher who knows that Black populations have higher rates of asthma and attributes this to genetic differences, reinforcing “abhorrent, long refuted, and disproven theories about biological race” instead of focusing on the legacy of structural racism in housing.1 She emphasized the need to support practitioners regardless of their education pathways in public health. ChangeLab examined 190 accredited schools and programs of public health across the United States and found that only 13 schools or programs have at least one course that addresses public health law topics that are required for graduation. Of these programs, only 3 M.P.H. programs and schools require a public health law course to graduate. She added that it is not enough for schools to train future practitioners about the law—degree programs should build their skills in areas such as community engagement and advocacy. Furthermore, Johnson cited research showing that of the 68 accredited schools of public health in the United States, not one requires an advocacy course to graduate with an M.P.H. (Carter et al., 2022). Johnson said that workers need support after they enter the field. She described the resource library for practitioners, available from ChangeLab, and encouraged the audience to explore further.2

Johnson then spoke about structural needs. She stated that furthering health equity—a strong interest for the field—will require a focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion in the public health workforce. However, applying an equity mindset, especially racial equity, is a novel concept for many working in public health, perhaps in part because, according to the 2019 National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) profile,3 90 percent of local health department executives are White. Recognizing the need to address power and privilege in public health, some health departments are taking action. For example, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene launched “Race Justice,” which is a multi-faceted effort to advance racial equity and social justice across all programs, policies, and practices.

Johnson concluded her presentation by describing seven areas that ChangeLab has identified for supporting the population health workforce:

- Develop government budgets that provide flexible, sufficient, long-term, consistent funding and investment in public health.

___________________

1 See, for example, Mersha et al. (2021).

2 https://www.changelabsolutions.org/good-governance/phla/resources-students and https://www.changelabsolutions.org/product/tools-change (both accessed July 27, 2023).

3 https://www.naccho.org/profile-report-dashboard/leadership (accessed July 27, 2023).

- Ensure equitable pay across workforce; prior to pandemic, some of the largest contributors to staff turnover were low wages and salaries.

- Develop policies supporting workforce health and mental health and well-being. Johnson cited a CDC statistic that 1 in 5 public health workers reported that their employer did not allow them to take time off.4 Johnson emphasized the need for policies that provide protection to these employees and offer them time and space to “recharge.”

- Provide protection against harassment: 12 percent of the public health workforce has been threatened on the job.

- Institute hiring policies that support a representative workforce, specifically those that make it easier to hire people who have been involved in the criminal legal system.

- Institute policies that support hiring professionals with specific policy and law expertise such as attorneys, policy experts, and people with skills in community engagement and grassroots advocacy; and

- Judiciously use licensing and credentialing regulations—to ensure both the health and safety of the public and the accessibility of critically needed public health services. For example, a 2019 study found that one-half of U.S. children with a treatable mental health disorder had never received treatment from a mental health professional.5 Johnson opined that state laws and policies greatly affect children’s mental health care access. Certain states may foster the growth of behavioral health workforce, while others may act against it. It is important to understand the context of these pathways and how credentialing may play a role.

Shauneequa Owusu began her remarks by asserting that a key component of public health practice and advancing health equity is creating community engagement, adding that equity principles guiding such engagement can insure they benefit community and respect its agency as opposed to being extractive.6 Furthermore, key partners are often community-based

___________________

4 https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/08/05/the-pandemic-has-devastated-the-mental-health-of-public-health-workers (accessed July 28, 2023).

5 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2724377?guestAccessKey=f689aa19-31f1-481d-878a-6bf83844536a (accessed July 28, 2023).

6 The speaker did not define the term, but it is widely used in the field to describe behavior that captures resources—effort, time, data, ideas—without proper recognition or compensation.

organizations (CBOs), which play a critical role in the public health system, she said, and are “indispensable” as part of wider public infrastructure. Owusu argued that CBOs are often underfunded yet they provide vital services and support. First, CBOs are a significant segment of the population health workforce. Second, they serve as an important link between government and community. Third, they use partnerships to extend their reach and impact. Finally, these organizations connect residents with engagement opportunities. Owusu added that CBOs play a critical role in connecting community members with emergency services when they are needed. During the COVID-19 pandemic, CBOs demonstrated a unique role by identifying gaps in local and state response and creatively meeting community needs. They also distributed funds, materials, and resources to families to help avoid evictions, afford necessities, and minimize negative health outcomes. Further, CBO relationships with communities make them trusted entities, enabling communities to better understand the pandemic and public health regulations. Owusu provided insight on how CBOs have been operating in California and how they have made a difference in meeting community needs. First, they implemented a person-centered strategy to address peoples’ immediate needs, which was emphasized as an “equity-forward” principle. CBOs put people in the forefront by using community-defined practices and person-centered strategies while providing culturally and linguistically competent services. CBOs tend to employ community members, and they have high rates of success working with community residents, building trust, and assisting community members navigate services. One CBO she spoke about deployed community health workers to meet the needs of their communities. She also discussed how CBOs in California responded to the trauma and fatigue experienced by low-income residents navigating complex and unresponsive government programs and systems through a trauma-informed approach to delivering services. This approach acknowledges individuals’ humanity and relieves the burden of applications and unnecessary travel. For example, CBOs partnered with service providers to deliver food and hygiene packages, while disseminating public health and other educational materials. Another key principle, Owusu stated, was “meeting people where they are.” She stated that during the pandemic many people could not access public transportation or chose to forego it because of safety concerns. As a result, some people were immediately cut off from basic resources, appointments, and social connections. California CBOs have kept community members engaged and informed through social media platforms and other tools during a time of crisis, when it was crucial to have a trusted source to provide accurate information to those in need (see Figure 2-1).

SOURCE: Owusu presentation, February 28, 2022.

BOLSTERING A NATIONAL POPULATION HEALTH WORKFORCE

The third panelist, Kyle Bernstein began his presentation by differentiating between population health and public health. First, population health, he described, is “an approach [that] focuses on interrelated conditions and factors that influence the health of populations over the life course, identifies systemic variations in their patterns of occurrence, and applies the resulting knowledge to develop and implement policies and actions to improve the health and well-being of those populations” (Kindig and Stoddart, 2003). It is concerned with the aggregate or population as opposed to individual. Finally, the goal is “to improve the health of groups and reduce health inequities between populations,” said Bernstein.

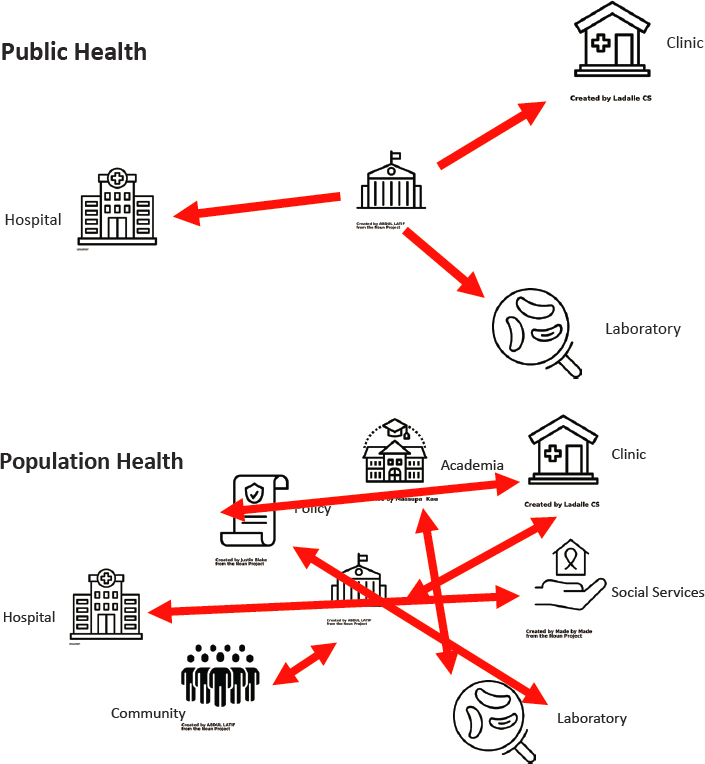

Regarding public health, Bernstein described it as what “we as a society do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy” (IOM, 1998). Bernstein also added public health has a greater focus on [the role of] government and does not prioritize the role of the health care system or other partners (Diez Roux, 2016). Bernstein offered a heuristic to illustrate how a public health system works in the United

States. The role of government (e.g., state, local, federal agencies) are central to this framework, while clinics, laboratories, and hospitals are satellite settings.

In the case of population health, Bernstein said, the depiction (Figure 2-2) includes such partners as social services, community members (individuals and CBOs), policymakers, and academic research partners. Moving beyond the public health graphic, which focuses on how government influences the other actors, Bernstein then discussed how each of the actors play an interconnected role across all domains, reflecting that health is a multifactorial issue, and supporting the idea that population health should be seen through the lens of health equity. Speaking of the importance of building a national public health workforce, Bernstein offered a Chinese proverb: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.” To illustrate, Bernstein showed a schematic illustrating how a population health workforce pipeline could be implemented. Primarily, he suggested, awareness and interest in population health should be generated during a general high school education, adding that one of the “bright spots” of the COVID-19 pandemic is that population health is now at the forefront of thought in younger populations. Next, awareness should be cultivated through coursework, internships, grants, and fellowships during undergraduate education. Additionally, graduate and professional schools should offer formal training programs (e.g., master of public health and other graduate-level training), grants, and fellowships. Finally, graduates who enter the population health workforce should be rewarded with promotions and career ladders, fair compensation, and incentives such as student loan repayment designed to attract and retain a skilled population health workforce.

Bernstein then spoke about gaps that exist in population health. He presented a study that examined the Public Health WINS 2017 Survey (de Beaumont Foundation et al., 2019), which surveyed public health departments and the workforce. He noted that although the data presented were from several years ago, they still highlight relevant areas where the population health workforce lacks capacity. For example, public health informatics and information technology specialists constitute a shrinking proportion of the workforce. He emphasized that in a large public health department, these areas of expertise represent only 0.5 percent and 1.3 percent of staff, respectively (de Beaumont, 2019). Bernstein emphasized that these positions are critical, with the COVID-19 pandemic pointing to the need to integrate, absorb, distill, analyze, and disseminate data.

SOURCE: Bernstein presentation, February 28, 2022.

Data collected on the changes in public health workforce between 20147 and 2017 indicated a decline in public health worker satisfaction across multiple job categories. The data also showed substantial declines in satisfaction with their organization, pay, and job security. Furthermore, data from the PH WINS 2014 and 2017 surveys highlighted a need to train new talent into the pipeline while retaining current talent. The data showed decreases in areas such as professional self-worth, training assessment, the

___________________

7 https://debeaumont.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Report.pdf (accessed July 28, 2023).

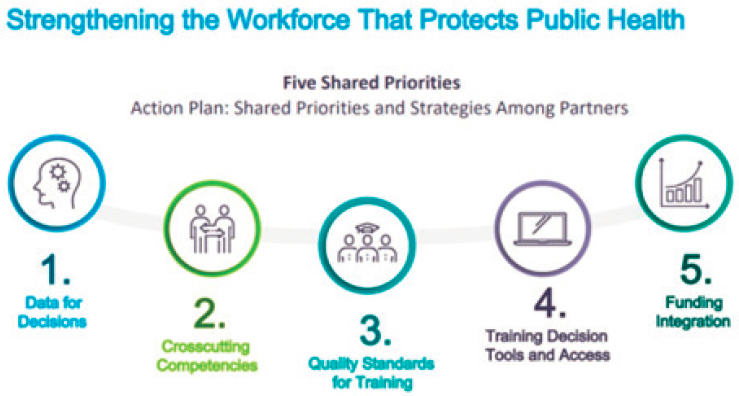

value of expertise, professional relevance, and sufficient technology training. Considering these findings, CDC has identified five priorities to help strengthen the workforce that protects public health (see Figure 2-3).

- Data for decisions: “data about workforce gaps and training needs to help inform population health workforce development.”

- Crosscutting competencies: to “complement public health workers’ discipline-specific skills.”

- Quality standards for training: using accepted education standards to guide our investments towards high-quality products and training programs.”

- Training decision tools and access: “define [workers’] training needs and locate high quality training that address these needs.”

- Funding integration: “integrate workforce development into funding requirements to build workforce capacity and improve program outcomes.”

Bernstein summarized a report that listed several strategic skills that are important to ensuring an effective governmental public health workforce including systems thinking, change management, persuasive communication, data analytics, problem solving, diversity and inclusion, resource management, and policy engagement (de Beaumont, 2017b). Bernstein commented that the skills listed are “not necessarily the domain-specific skills that we think about in terms of public health training, but

SOURCE: Bernstein presentation, February 28, 2022; https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/documents/action-plan-snapshot-508.pdf (accessed July 28, 2023).

more of those cross-cutting skills… which are critical regardless of the discipline you are studying at the undergraduate and graduate level, and are increasingly important, not just for government public health workforce, but for all of us working in population health.”

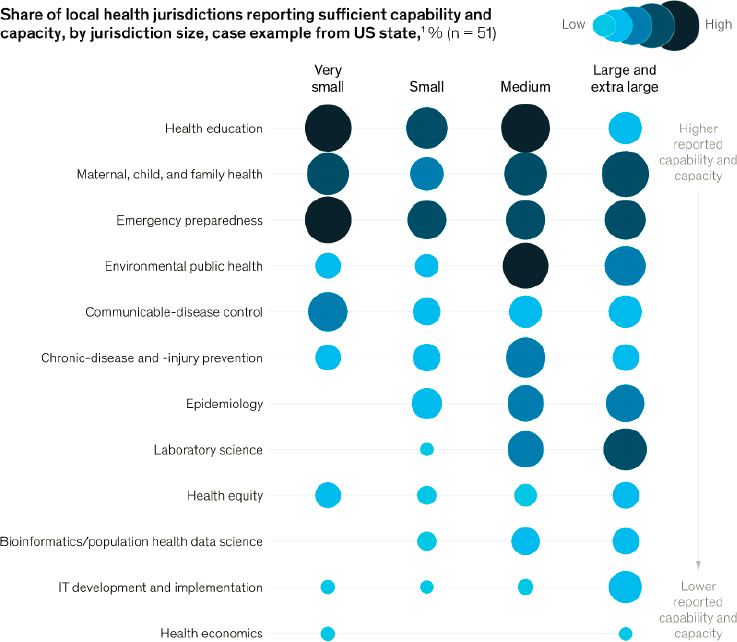

Bernstein concluded with several points from a McKinsey & Company report titled Building the U.S. Public Health Workforce of the Future (Kumar et al., 2022). The report “assessed capacity and capability amongst various health departments with respect to areas of expertise,” Bernstein said. The workforce domains highlighted in the McKinsey report included health education; maternal, child, and family health; emergency preparedness; environmental public health; communicable-disease control; chronic disease and injury prevention; epidemiology; laboratory science; health equity; bioinformatics/population health data science; information technology development and implementation; and health economics. Bernstein shared a figure (Figure 2-4) that illustrated capability and capacity in the various workforce domains in health departments of varying sizes. For example, Bernstein noted, in the domain of health education, there is a “fair amount of capacity” versus “stark deficiencies” for capacity building in domains of epidemiology, laboratory science, health equity, bioinformatics/population health data science, information technology development and implementation, and health economics. In epidemiology, there is limited capacity at smaller health departments, while at the medium- and larger-sized health departments the opportunity for capacity is “not ideal,” said Bernstein. Furthermore, laboratory sciences is another domain that lacks support at smaller health departments, while there is a robust level of support at the larger health department level. Finally, in the domains of health equity, bioinformatics/population health data science, information technology development and implementation, and health economics there is “very low capacity regardless of health department size,” Bernstein explained.

Bernstein described several fellowships offered by the CDC Foundation that are specifically aimed at addressing some of these capacity gaps. For example, the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) is a 2-year experiential fellowship program that is designed to train the next generation of epidemiologists. Further, CDC has established the Laboratory Leadership Service, which trains laboratorians to work in the public health setting, while the Public Health Informatics Fellowship Program is a 2-year experiential fellowship program that aims to train public health practitioners, computer scientists, and data scientists to work in population health. Finally, the Steven M. Teutsch Prevention Effectiveness Fellowship helps to develop economists, mathematical modelers, and health service researchers at the intersection of population and public health. Bernstein

SOURCES: Bernstein presentation, February 28, 2022; Kumar et al., 2022. Exhibit from “Building the US public-health workforce of the future,” February 2022, McKinsey & Company, www.mckinsey.com. Copyright © 2023 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

reiterated that these programs approach health as the endpoint of multiple factors and focus on furthering health equity.

At the close of his presentation, Bernstein shared the link for CDC fellowships8 and provided a summary of key points. First, population health “has suffered from decades of infrastructure decline and disinvestment.” Second, acting now and in the immediate future has the potential to increase the “abundance of resources and broader appreciation for the value of population health.” Third, to bolster the public and population health workforce pipeline, study is needed to determine what approaches work best at each stage.

___________________

8 www.cdc.gov/fellowships (accessed July 28, 2023).

POLICY AND OTHER OPPORTUNITIES FOR STAKEHOLDERS

Moderator Smith underscored the distinction that Bernstein had made between population health and public health, and he remarked on the importance of the “strategic skills necessary” to advance population and public health, citing gaps between worker experience and their expected responsibilities. Smith then introduced the final panelist, Joshua Sharfstein, who spoke about the future of policy as well as about other areas that could be addressed and acted upon based on prior panelist presentations.

Sharfstein began by describing the historical tension that has existed within the field of public health between the “more narrow and more expansive view of the job of public health” and how a comprehensive definition of public health plays a critical role in addressing key issues for the public health workforce. Referring to the previous speakers’ remarks, he said they showed why the definition of public health should not be limited to discrete sanitary measures but rather extend to fundamental health inequity for the population at risk.

Sharfstein then offered a distinction between what he referenced as the “active” public health workforce and the “latent” public health workforce. He defined the active public health workforce as those who would, if they were stopped in the street and asked what their jobs were, answer that they were “working to improve the health of their community…or their county or state.’” By contrast, Sharfstein defined the latent public health workforce as people who are doing work relevant to improving the health of a target community but whose participation in the health workforce may be “hidden.” Based on this framework, Sharfstein divided the public health workforce into four parts: governmental public health organizations, the medical and health care system, CBOs, and policy makers. Governmental public health organizations are all part of the active workforce, he said, and most people “should know that they are working for the health of the population.” A major issue facing this workforce is funding, as tens of thousands of people are leaving government public health agencies.

Another key issue within governmental public health, Sharfstein described, is its composition, adding that the concept of how community health plays a role in formal governmental public health workforce has recently been broadening. For example, Sharfstein said that “hundreds of community health workers were brought into the COVID response” in areas such as Chicago and Baltimore, and the response to the idea of having a permanent “community health-public health workforce that can address many different challenges in health…in communities” has been enthusiastic. He also said that the public sector of the public health work-

force needs “protection” from harassment and mistreatment, echoing an earlier point by Owusu and Johnson.

The second component of public health workforce, the medical or health care system, has both active and latent public health workers, Sharfstein said. For example, many public health professionals are responsible for population health or community health within a health system or community health center and are aware that responsibility is part of their jobs. In contrast, other professionals may be unaware that the work to which they contribute is related to public health, or believe they contribute to public health, but their work is not directly related (i.e., they are members of the latent workforce). He attributed the differing understanding of roles to how definitions of population health can vary depending on the role of the health care worker. For example, Sharfstein said, “Many people in the health care world define population health on an attributed population basis…like just the people covered by a certain insurance company or just the people who show up in a particular clinic rather than a population in a geographic sense.” Sharfstein said that a key challenge of this part of the public health workforce is “to orient the health care system to the health of their communities through fundamental financial incentives around health care. I think it’s very hard for people really to be oriented to the health of their community unless that is their mission and focus as a health care organization.” Sharfstein said that it is imperative that these professionals can view population health data and have a comprehensive understanding of tools available, including community mobilization strategies relevant to population health, as opposed to one-on-one medical attention to improve health.

CBOs, the third component, are an essential element of the public health workforce, Sharfstein said, and an important goal should be to build strong networks between governmental public health organizations and CBOs. These networks, highlighted during COVID-19, worked to bring people from the latent public health workforce to the active public health workforce. Sharfstein explained how a public health worker “may think their focus is on transportation or their focus is on housing reform. But bringing them into a public health coalition, working with them, that is a really important step.” It is important to provide support for those working in the latent workforce, such as through training opportunities and the provision of public health tools to their organization.

Sharfstein described an activity his own organization has implemented to support the latent workforce: The Bloomberg American Health Initiative9 (Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, 2020). This program provides 60 full scholarships to professionals working on key health

___________________

9 https://americanhealth.jhu.edu/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

issues in the United States each year. These scholarships are awarded to professionals working in sectors such as education, housing and urban development, food security, and community safety. This program, he said, seeks to move public health “in the direction of organizations on the frontlines and at the same time strengthen those organizations.”

Among the fourth segment of the public health workforce, that is, policymakers, Sharfstein said that not all people who are clearly doing public health-related work, recognize that this is what they are doing. To address this issue, Sharfstein recommended providing tools to policymakers, such as impact assessments and policy briefs, to move their work from latent to active and “inspire them to align their work” with public health.

In closing, Sharfstein said that funding, health workforce composition, and protections for public health workers are topics of critical importance in Congress.

After thanking Sharfstein, Smith spoke briefly about the CBOs supported by the CDC Foundation to help respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. These groups do not have health care titles, she said, but they nevertheless play a role in public health. “They might be working on advocacy for migrant farm workers or agriculture workers. They might be working to address or end homelessness in a particular area. They make be engaging through civic engagement and mobilization for voting.” Sharfstein responded that this notion of engaging with these groups is “exciting and mutually beneficial” and added that activities such as the Bloomberg American Health Initiative that are not traditional public health partners can prompt collaboration.

DISCUSSION

Recalling the comments by Owusu and Johnson about revitalized graduate public health curriculums to meet 21st century workforce needs, especially in the areas of policy and law, Smith referred to the “unprecedented” increase in public health funding at the state and local levels to address previously mentioned workforce challenges. What, she asked, should public health organizations at the state and local levels do to ensure that these new funds are used optimally?

Bernstein acknowledged that it is a challenge to optimize the uses of funding, especially when “we generally don’t get a lot of resources in public health.” The challenge is further complicated by various restrictions on the funding such as timelines and talent recruitment in state and local programs. He pointed to potential areas for opportunity. One involves strategic evaluations of competencies that could be conducted across disease programs at state and local health departments. “There is more flexibility in sharing some of those resources across categorical pro-

grams than I think state and local health departments are leveraging,” he said. He also spoke about the importance of thinking creatively in terms of recruitment of population health workforce talent. “There are really incredibly skilled people that aren’t in places that we traditionally look, like our CBOs, and not necessarily the CBOs that are health-centered” he said, emphasizing that workers who are employed by CBOs have desired skills that could benefit public health and have the potential to develop into the next generation of public health leaders.

Sharfstein agreed with Bernstein’s comments and said there is a “challenge for public health departments to spend money” if there is inadequate capacity and guidance for doing so efficiently and effectively. He cited the mayor of Chicago, who underscored the importance of building not “temporary scaffolding” but permanent capacity during pandemic response. Sharfstein also emphasized the role of national leadership. Referring to a then-recent CDC funding notice for state and local health departments, he said, “It’s going to be very important for there to be some real guidance because we need a basic structure in this country instead of a collection of different kinds of approaches.” Besides having common standards across health departments, he continued, it will be vital to take a thoughtful approach and not rush things when deciding on agency efforts.

Johnson shared the link to a recent CDC Foundation public health law and finance summit as a resource relevant to the discussion.10 Chowkwanyun, referring to the ChangeLab’s presentations, said that it is also his experience that public health students have less training in public health law and the policy process (e.g., the introduction of a bill to appropriation). He said that people in leadership roles in state and local agencies tend to have that information but people at the mid- and lower levels are not keeping track of things that are occurring in the legislature. But perhaps they should, especially if they have an idea that could be very compatible with a new emergency or one-time appropriation.

Smith turned to the first audience question, asking panelists how nurses and other professionals could bolster public health given the lower pay in some public health roles. Sharfstein acknowledged that it is important that “people are paid well and fairly” but said, “I don’t think it’s realistic in the short term we’re going to see [public health] salaries that really compete with serious clinical salaries.” Sharfstein further commented that despite salary disparities between public health professions and clinical care, people are still drawn to public health because there

___________________

10 https://www.cdcfoundation.org/pr/2022/public-health-law-governance-finance-summit (accessed July 28, 2023).

are “enormous rewards.” Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected those rewards, particularly via the harassment and mistreatment that public health professionals have experienced. Thus, he said, supporting the public health workforce must go beyond just improving the salaries. Sharfstein said that public health nursing has an incredible history that goes “well beyond giving shots or being the school nurse.” Public health nurses are responsible for developing public health programs, working on social causes of health, and bridging the gap between social issues and clinical care. He endorsed the notion of reinvigorating public health nursing through incentives such as loan repayment, as cited by previous panelists.

Bernstein responded to Sharfstein’s comment about salary disparities and market pressures. Concerning the disparities that exist between public health professionals and clinical professionals, Bernstein pointed to the disparities that exist between the public sector and private industry and suggested that those disparities impact public health. Laboratorians, informaticians and data scientists are well-trained professionals in highly technical fields and are therefore able to seek opportunities outside of public health, he said. To effectively recruit and retain the public health workforce, he stressed, “we have to be realistic about how we can compete… Loan repayment incentive could play a critical role… but we have to be really strategic and, I think, really pragmatic.”

Smith then posed another question from the audience: “Given stark racial inequities in many health outcomes how should health departments invest in preparing their workforces to be anti-racist workforces?”

In response, Owusu pointed to New York City’s Race to Justice initiative that is embedded in the health department.11 “It’s not just about laws and policies and procedures to advance health equity within New York City, but also a critical component of that is training their workforce internally,” she said. The New York City Health Department has successfully implemented this curriculum, which is divided into several modules and operationalized based on department structure, in an agency with more than 6,000 employees. The success of Race to Justice is particularly notable, she said, because there are “practicalities and challenges that can come with training a workforce and staff” such as training curriculum composition, utilization, and implementation, while addressing critical needs in the community.

Johnson spoke about the differences among health departments at the state and local levels. For instance, Johnson stated, “in some places we’ve heard, they’re not allowed to say the words ‘equity’ or ‘racial equity.’”

___________________

11 https://www.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/race-to-justice.page (accessed July 28, 2023).

How can people working in these environments make a difference? She suggested choosing different words, using data to start conversation, building partnerships with external partners, pulling in partners who can make the case for why change is needed, and finding ways to conduct work even when the environment is hostile. These are all essential components to being able to “move the needle” wherever and whenever feasible.

Smith mentioned the CORE Initiative conducted by the CDC Foundation, an effort to “drive and promote health equity within the CDC itself.” The E in CORE stands for “Enhancing Capacity for Workforce Engagement” on health equity.

Bernstein reiterated that CDC has taken a “forward facing and proactive approach issued around diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in all of its work,” emphasizing that these efforts are no longer stand-alone, but rather are integrated “within everything that we do.” Bernstein said that all employees who conduct interviews or assess applications for the CDC fellowships must complete unconscious bias training to counter bias in fellowship applicant selection. The goal of the training, he said, is to “increase the workforce from a Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) perspective.” Furthermore, he added that DEIA-related case studies are woven into public health contexts across all fellowship programs. He also shared that there has been a change in perspective at CDC, with the agency recognizing that consideration of DEIA is critically important to public health. Bernstein finalized his remarks by emphasizing the importance of interpersonal work in achieving these goals.

Smith then asked the panelists, “Can you share any examples of law or policy modernization pertaining to the workforce that could benefit other states or locales?” Sharfstein spoke about opportunities for community health workers to be directly reimbursed through Medicaid. Earlier, as part of a 2019 roundtable workshop, Sharfstein had described how the Maryland health care system used funds from budgets to hire community health workers to improve population health in different parts of the state—using the payment system to support a shift. Sharfstein said it is important to pass legislation that explicitly protects public health workers from harassment.

The next question concerned the public view of the public health workforce regarding trust and recognition. Smith asked the panelists for suggestions about actions that the public health workforce could take to reinforce trust and the recognition of expertise and experience. “This is not going to be something that changes over night,” Johnson said, because the breakdown of trust has been “centuries in the making.” She said that CBOs have an important role to play because they have dedicated time to meet with community members in community settings, such as churches,

schools, and community festivals to rebuild a sense of trust. She also suggested that CBOs could partner with various sectors to combat misinformation on social media. Owusu agreed with Johnson’s remarks and added, “The workforce must reflect the community in which it serves.”

In the panel’s closing remarks Chowkwanyun emphasized that the COVID-19 pandemic has posed a confusing situation for society, and he suggested that a “restoration of faith” in public health infrastructure could help meet the current challenges we are still facing because of the pandemic. Chowkwanyun added that early in the pandemic there was discussion about building something better, and the field should avoid growing cynical and tap into that sense of potential of expanding public health infrastructure. Sharfstein stated that the public health workforce had been largely invisible prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. He highlighted that the public health workforce is now more visible due to internal reflections conducted by organizations, academia, and government agencies. Sharfstein also emphasized that partnerships are needed to cultivate public health visibility and value. He concluded, “It is a different world we are in, post-pandemic, and history informs that world, but we’re not bound to necessarily have the same experiences we had before.”

Bernstein remarked that there is potential for change and advancement of knowledge. He said, “Where there are challenges, there’s opportunities. I am really excited about the number of resources that are coming with respect to bolstering the [public health] workforce and opportunities to really think about how we can leverage those resources the most effectively to have the longest long-term impact.” Johnson specified that creating change is a long process. She analogized that public health “is a marathon not a race” and encouraged the audience to visit her organization’s website, ChangeLabsolutions.org, for additional resources and technical assistance.