A Population Health Workforce to Meet 21st Century Challenges and Opportunities: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 3 Exploring Solutions to Workforce Challenges

Valerie Yeager, an associate professor at Indiana University Fairbanks School of Public Health, opened session two by outlining her research interests on public health workforce recruitment and retention. Over the past two decades, she said, schools and programs of public health across the United States have trained “exponentially” more students in public health, yet these formally trained workers have fallen short in governmental settings. “There are shortages of specific skillsets across the workforce,” she said, repeating a theme from the previous panel. She also reported that the number of employees in state and local governmental public health declined by 16 percent since 2008 and 2019 (Leider et al., 2023), which, she said, “sets the stage for understanding the Staffing Up Project’s recent estimate that an additional 80,000 full-time employees are needed to meet the foundational public health services.” Yeager emphasized how recruitment and retention of employees who have appropriate public health training and also reflect the population being served “is an important, ongoing issue.”

Yeager described the objective of the second panel as examining innovative approaches that could meet public health workforce and community needs. She then introduced eight panelists: Theresa Chapple-McGruder, director of Oak Park Department of Health, Illinois; Dave Chokshi, 43rd Commissioner of New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Kimberly Fowler, vice president of the Technical Assistance and Research Center, National Council of Urban Indian Health; Kusuma Madamala, public health systems and services researcher, Oregon Health Authority; Sara Beaudrault, a policy analyst at the Oregon Health Authority; Michael Baker, health officer of Jefferson County, Oregon; Nicole Alexander-Scott, former director, Rhode Island Department of Health; and Renée Branch Canady, chief executive officer, Michigan Public Health Institute.

LEADERSHIP DISPARITIES IN GOVERNMENTAL PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCIES

Chapple-McGruder began with a brief overview of her presentation on leadership disparities in governmental public health agencies. Explaining that she has spent her entire career at state and local public health agencies or organizations that support governmental public health, Chapple-McGruder highlighted that she noticed disparities in governmental public health leadership. As a doctorate-trained epidemiologist, she said, she wanted to further research disparities in leadership to identify whether or not they were isolated events or common throughout governmental public health.

Noting that it took five decades for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to employ its first African American director, David Satcher, and another decade for the agency to employ its first female director, Julie L. Gerberding, Chapple-McGruder remarked that CDC has yet to employ an individual from any other ethnic group as director. Despite improvements in diversifying the leadership at CDC, Chapple-McGruder stressed, “there is a long way we still have to go before top leadership of the nation’s number-one public health department or leading public health agency becomes more reflective of the country which it leads.” She then discussed governmental public health workforce diversity at the state and local levels, beginning with data showing that the state and local public health workforce is predominantly female. According to the de Beaumont Foundation et al. (2017a and 2019), 72 percent of the state governmental public health workforce was comprised of female employees in 2014, a figure that increased to 78 percent in 2017. This pattern is not limited to governmental public health, she said. “We see this in academia, we see this in the nonprofit space, that public health is an overwhelmingly female-dominated career.” She also reported that in 2017 only 27 percent of state and local health department employees were supervisors, while only 30 percent of state governmental public health employees were supervisors.

Chapple-McGruder also commented on gender differences in leadership in state public health agencies. Chapple-McGruder found that among state public health agencies, 67.1 percent of leadership roles were women in 2014. However, this figure is not indicative across all leadership roles at the state governmental public health level. In fact, Chapple-McGruder’s research found that while 69.4 percent of supervisor roles and 68.8 percent of manager roles were female employees in 2014, only 54.7 percent of executive leadership roles were female employees that same year. Chapple-McGruder said she initially hypothesized that these differences might be a result of educational attainment and/or prior professional or management experience. However, after controlling for these factors,

she found women were still about 45 percent less likely than men to enter executive leadership positions at state governmental public health agencies. These results prompted Chapple-McGruder to investigate pay equity, especially among those in leadership positions, and she found that women were 36 percent less likely to work in high-earning bracket categories at state public health agencies, regardless of leadership level. Given this research, Chapple-McGruder said it is important that there be equal representation at all levels of the governmental public health workforce. “What is it that we are willing to do amongst our workforce,” she asked, “to ensure that women are given opportunities to rise to the highest levels, making sure our voices are ‘at the table,’ that we are part of those who are having the final decision…when it comes down to the health of the community?”

Chapple-McGruder then reiterated Yeager’s comments that although the number of trained public health professionals has risen, the percentage of people who have been trained in public health has decreased. For example, only 14 percent of the public health workforce possessed a degree in public health in 2017 (de Beaumont, 2019). This is a 3 percent decrease from 2014, when 17 percent of the public health workforce possessed a degree in public health. “While I am not one to say that I think that all state and local health departments may be staffed with 100 percent of people with M.P.H.s or public health degrees,” Chapple-McGruder said, “I do think that there are specific things that are taught in public health programs that local and state health departments may not have good representation of because we don’t have a good number of people in our organizations that have public health degrees.” For example, she said, health equity and prevention are two important framing elements in the work of public health that are inadequately reflected in many public health agencies. Furthermore, results from a 2014 survey of public health workers (Sellers et al., 2015) indicated that epidemiologists do not possess the necessary skillset to perform one-third of their daily work requirements. These examples indicate a need to provide adequate training for governmental public health agency workers to meet the needs of the communities in which they serve, she said. In conclusion, Chapple-McGruder said that well-established workforce pipelines and partnerships could play a role in addressing the workforce gaps and challenges.

NEW YORK CITY PUBLIC HEALTH CORPS: LESSONS FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC RESPONSE

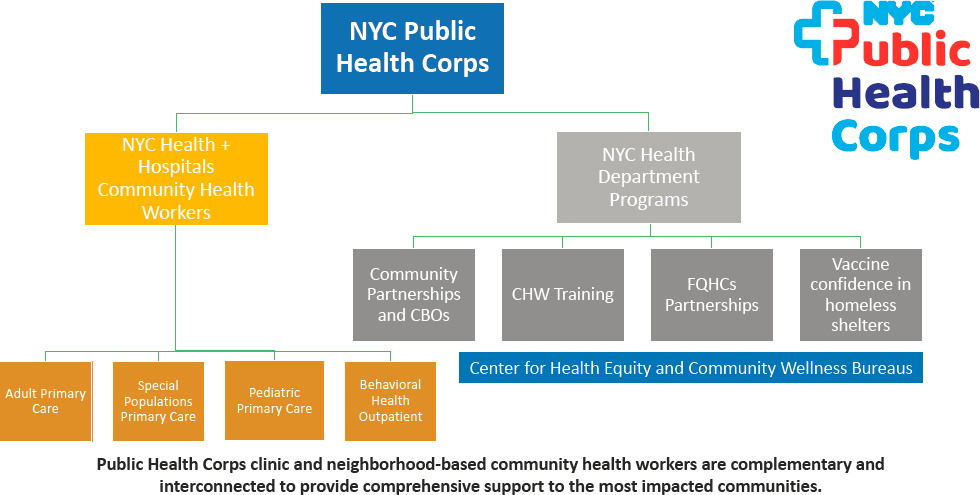

Dave Chokshi, commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene began his presentation by describing the New York City Public Health Corps (Figure 3-1).

NOTE: CBOs = community based organizations; CHW = community health worker; FQHC = federally qualified health center.

SOURCE: Chokshi presentation, February 28, 2022.

Chokshi said that as society continues to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to discuss the investment needed to place the public health workforce in a strategic position to respond appropriately to future public health emergencies. Chokshi described the “hyperlocal approach,” which centered around New York City’s most affected communities (Chokshi, 2021). This approach was grounded in available data, which indicated that the communities affected the most by the COVID-19 pandemic were the same communities that historically have experienced the most disinvestment and poor health outcomes. Chokshi said that the hyperlocal response required building upon already existing assets in these communities, providing further investment, and listening with humility to people “on the ground” to understand what kind of supports were needed—particularly material resources. For example, in the Tremont section of the Bronx where COVID-19 rates were approximately twice as high as in other parts of the city the population is 67 percent Latino, 25 percent Black, and 1 percent White, and 30 percent of residents live below the poverty line and 22 percent do not have health insurance coverage.

Chokshi also described an “assets-based approach” of tapping into a network of existing CHWs, faith leaders, care providers, and nonprofit organizations (including ones that are community-based)—especially those who have earned the trust of community residents whom they were serving. Chokshi said that community-based organizations were crucial when deciding where to place an accessible testing center where community residents could receive services. Additionally, staff who were themselves Tremont neighborhood residents helped with outreach by explaining testing and directing residents to the site. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene also engaged with other partners, which provided a network for residents with resources if they tested positive for COVID-19, including local food pantries, food delivery, mental health services, and health insurance, which Chokshi described as “vitally important.” He emphasized that the efforts in the Tremont neighborhood “were focused on the needs of that community.” Community residents helped to promote services in ways that were beyond what the official channels that New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was able to access and “lent credibility to the effort.” In vaccine canvassing, for example, Chokshi noted, it helped that public health workers had “boots on the ground and [were] present in a way that allows people to build trust over time.”

Switching to the topic of building public health infrastructure for the future, which he described as “fundamental as roads and bridges,” Chokshi proposed short-term, medium-term and long-term goals. Short-term goals included reducing gaps in vaccination rates by race/ethnicity/

geography and age; helping public hospital patients address barriers to health and well-being, improving primary care engagement, and reducing avoidable acute care use. A medium-term goal was expanding investment in public health infrastructure in the most affected neighborhoods. The long-term goal, he added, is a just recovery from COVID-19 and achieving health equity goals.

Chokshi also spoke about key public health corps activities such as health education and promotion, health and social service navigation and referral, and community needs assessment and collective action for policy change. He described the Public Health Corps as a “nation leading investment in the public health workforce…with and for communities that have been disproportionately impacted,” through 250 CHWs hired thus far. These are health care system-embedded CHWs who work in outpatient clinics in pediatrics and behavioral health with a focus on special populations, for example, people experiencing homelessness or people recently returned from incarceration.

Chokshi highlighted the importance of this integrated public health system in terms of meeting patients’ needs. He said,

There are so many patients we do not see, who never make it into the health care system in the first place until they are in extremis, or until crisis. That’s where the public health department’s role in fundamentally important: to help with navigation; to help with connecting with both health services and social services; to uncover undiagnosed illness… and to ensure we marry our primary and secondary prevention approaches with the tertiary prevention that the health care system is responsible for.

He also described preliminary outcomes on COVID-19 vaccination uptake from the Task Force on Racial Inclusion and Equity (TRIE) initiative.1 The $235 million program engaged community and faith-based organizations and the NYC Health + Hospitals public safety net system and hired approximately 500 CHWs to administer vaccines. Within the first 2 months more than 15,000 vaccinations were directly administered, and since the program launched, more than half a million New York City residents have been connected to vaccines via appointment or accompaniment. Furthermore, data from the TRIE program showed that greater than 70 percent of adults from TRIE neighborhoods achieved full vaccination status, which significantly closed gaps in vaccination rate compared with non-TRIE neighborhoods.

Next, Chokshi reiterated the importance of investment in the future of public health. “We have a once in a generation opportunity, I believe, to

___________________

1 https://www.nyc.gov/site/trie/about/about.page (accessed July 28, 2023).

re-imagine what public health can look like in the United States,” he said. “This must be led by the people who are most affected and who know the communities that they serve.” In his closing remarks, Chokshi said that the demonstrated need for investment in public health should be scaled appropriately to ensure a sustainable community health workforce not only for future public health emergencies but also for other critical issues such as chronic disease, behavioral health, and health equity.

Yeager asked Chokshi two questions: First, “How do you sustain these employees as members of the population health workforce?” and second, “How do we reflect them in our enumeration efforts which have historically been taken under the wings of state health agencies, Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ Profile Survey or National Association of County and City Health Officials’ Local Health Department Survey?” Yeager said that there is not a good mechanism or metric to track population health workforce, as opposed to the official governmental public health workforce.

In response to the first question, Chokshi said it is vital to establish a sustainable public health workforce and take advantage of opportunity for investment to ensure future adequate response to health crises. For example, New York City supported public health workforce expansion through grant and federal funding to accomplish the previously mentioned early outcomes from the TRIE neighborhood initiative. Furthermore, increasing sustainable city investment may prove beneficial in easing fiscal reliance on government partners for adequate public health response. In response to Yeager’s second question, Chokshi said the current challenge of public health will evolve to include the community health workforce as a key element.

COMMUNITY HEALTH REPRESENTATIVES IN INDIAN COUNTRY

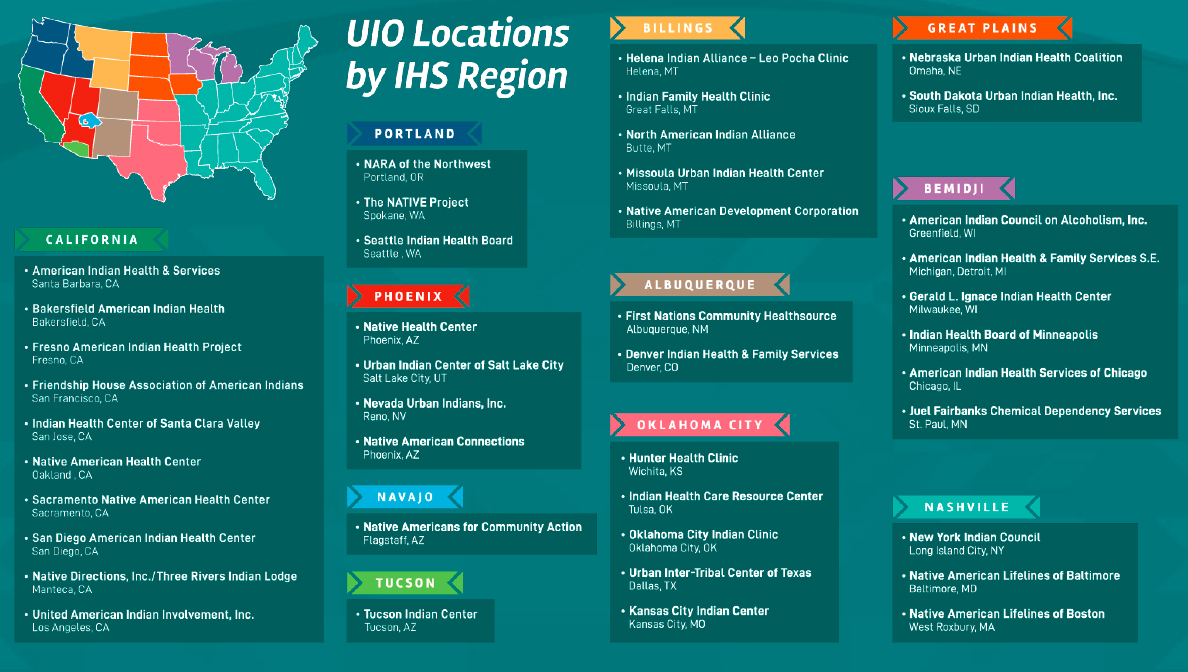

The next panelist, Kimberly Fowler, started her presentation with an overview of the National Council of Urban Indian Health (NCUIH), which she described as the national nonprofit that is dedicated to “the support and development of quality, accessible, and culturally competent health and public health services for American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN) living in urban areas.” Fowler said that greater than 70 percent of the total AIAN population in the United States live in urban areas. Public health and health care for this population is delivered through 41 Title V Urban Indian Organizations, which are federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) under the Indian Health Service (IHS). Fowler described how the IHS operates to provide context for workshop participants. First, she said in addition to FQHCs, IHS also works with

tribally run facilities that have compacts and contracts to provide health care to communities on tribal lands.

There are 41 Urban Indian Organizations (UIOs) in 22 states and 38 cities across the United States, organized into the 12 regions designated by the Indian Health Service (Figure 3-2). The services provided by UIOs include primary health care, traditional medicine, social and community services, and behavioral health services. Primary health care includes such services as general medical care, diabetes care and prevention, vision and hearing screenings, immunization administration, and women’s health care, among others. Behavioral health services include a wide array of inpatient and outpatient care such as mental health counseling, psychiatry, substance abuse counseling, education, and prevention services. Social and community services include initiatives dedicated to addressing the social determinants of health such as education and housing programs; youth camps; elderly services domestic violence services and classes; and employment support and placement. Fowler emphasized that some of these services can provide vouchers (e.g., housing) to support Native individuals and their families. Finally, the traditional medicine services, which support cultural activities and ceremonies for a holistic approach to health, include sweat lodge ceremonies; men’s, women’s and elders’ talking circles; traditional medicine from traditional healers; prayer ceremonies; and relationship gatherings. These interdisciplinary service types span a variety of UIOs from referral and outreach facilities to full ambulatory facilities that offer specialty care and residential treatment centers.

Fowler said that the coordination of care among UIOs is largely supported by the nonclinical public health workforce, such as community health representatives (CHRs), and that this workforce is essential for completing the continuum of care for primary care patients within indigenous communities. Fowler added that CHWs working at UIOs can support primary care patients through a variety of mechanisms. For example, they can serve as community health and public health educators and staff delivering interventions for HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections; or they may also support UIO programs such as Special Diabetes Programs for Indians (SDPI); Women, Infants, and Children programs; maternal, infant and child health programs; early education programs; and general wellness programs (e.g., fitness and nutrition education). Additionally, CHRs have coordinated school health and adolescent health programs and in-home health care programs for elderly and disabled populations. Fowler reiterated that CHRs and CHWs are essential pillars to achieving population health. She said, “They help to facilitate access to quality and culturally competent services and really provide that link between health and social services through this programming.”

SOURCE: Fowler presentation, February 28, 2022.

The next part of Fowler’s presentation centered on the IHS CHR Program. Fowler described the program as a “national program that was established in 1968 that provides training and management of over 1,600 frontline public health workers across Indian country and across 250 tribes.” An estimated 150 CHRs are involved in providing these services in urban areas. CHRs are trusted members of the community and provide that close understanding of language and its traditions, Fowler said. As previously discussed, the CHR program provides health care, health promotion, and disease prevention services for eligible individuals through a variety of state, local, and private funding mechanisms. IHS also provides CHR skills management training including the teaching of basic CHW worker skills sets or the maintenance of certification. Furthermore, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, IHS has implemented TeleECHO programs, which are community-level response trainings provided through the University of New Mexico and Indian Country ECHO CHR program series. ECHO trainings emphasize the social determinants of health and the public health scope of practices that a CHR can offer.

Fowler then spoke about some successful CHR outcomes achieved despite UIOs having limited or no funding. These outcomes included tribal cultural competence to increase health access and coverage; reduction in hospital admissions; reduction in mortality rate; and improved maternal and child health outcomes such as increased child wellness visits and vaccination registration in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Next, Fowler discussed the many challenges, solutions, and opportunities related to UIOs. First, operational and financial barriers exacerbated by COVID-19 posed perhaps the most significant challenge. Fowler advocated for additional funding to relieve these strains to better serve the AIAN communities. She emphasized that adequate funding could provide high-quality, culturally competent services to these communities. Fowler highlighted that NCUIH has succeeded in securing $63.7 million in funding allocated to urban Indian health through COVID-19 omnibus spending bills during fiscal year 2021.

A second barrier Fowler listed was the fact that patients are still adjusting to returning for preventive or chronic care as the pandemic wanes. “Local IHS hospitals have attempted to deter patients from heading to emergency rooms,” she said, and through CHRs they have been able to do so by providing in-home care, or at least having teleconferences that can occur to keep track of patients’ maintenance for chronic disease.

Third, Fowler emphasized that staff recruitment and retention is a persistent issue within all systems of care. “Urban Indian Organizations

have had to compete with for-profit health agencies that offer higher salaries, remote opportunities and sign-on bonuses,” she said. To respond to these competing agencies, many UIOs have implemented flexible work schedules, offered continuing education benefits, and negotiated salaries to sustain staff. UIOs have also offered various incentives, such as hazard pay. In addition, NCUIH has offered mental health workshops including applicable cultural traditions to build safe spaces for health care workers who have experienced compassion fatigue, burnout, and other mental health obstacles from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Numerous opportunities exist to help develop the delivery of effective and high-quality care to indigenous communities, Fowler said. For example, the “National Health Coach Pilot Project” was recently launched by IHS to “deliver health coach training to community and health professionals in Indian Country.” That project offered a 6-month training for two cohorts from April to October 2022. The goal is to explore the feasibility of establishing a health and wellness coach and behavior change approach at the clinical and community levels. Additionally, Fowler described the CDC-funded Project Firstline, which is NCUIH’s Infection Prevention and Control Project to support “standardization of policies, procedures, and protocols across the health care system.” Fowler concluded her remarks with a call for increased need of funding to support UIOs, establish new pathways to expand the CHR workforce, and improve physical environments that have been affected by COVID-19, and she acknowledged the CHRs who provide culturally competent in-home care and support, which is paramount to the success of the health and wellness of AIAN communities.

CENTRAL OREGON TRI-COUNTY PARTNERSHIP: OVERVIEW, CASE STUDY, AND REFLECTIONS

Yeager introduced three panelists from Oregon: Kusuma Madamala, Sara Beaudrault, and Michael Baker.

Beaudrault began by describing a cross-jurisdictional staffing partnership across three counties in Oregon. In 2015, she said, the Oregon legislature enacted a law that provided a new framework for governmental public health, similar to national foundational public health services model, which she described as “public health modernization.” The 2017 legislature allocated an initial $5 million investment to innovate Oregon’s public health system. These funds were awarded through competitive grant processes to eight local public health authorities.

Beaudrault said that the primary purpose of this funding was to establish regional partnerships for communicable disease control. To achieve this goal, partnerships developed regional systems for communicable

disease control; emphasized elimination of related health disparities; and built sustainable infrastructure for new models of public health service delivery. Regional service delivery has continued with additional funding in 2019 and 2021. “These regional partnerships are not about regionalizing or consolidating public health departments” Beaudrault said. Instead, they are about finding ways to support a public health workforce that can support communities in every single corner of our state.”

The Central Oregon Tri-County Partnership, which was the focus of the three presentations, was of the regional public health partnerships that were awarded funding in 2017, which includes Jefferson County, Crook County, Deschutes County, and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Beaudrault said that this area shares one hospital health system, one federally qualified health center, and one Medicaid coordinated care provider. Deschutes County is the largest of the counties in-terms of population size and therefore has access to a more robust public health workforce than the other two counties in the region.

Beaudrault said that central Oregon is known to be a leader among local public health authorities and applauded the fellow panel member Baker. The local health agencies in central Oregon have worked together to meet the needs of their shared community, Beaudrault said. Even prior to the 2017 funding announcement this partnership between local health authorities had already identified 10 areas of interest across their counties and the positions needed to support this work. After the funding became available, these local health agencies created the Central Oregon Outbreak Prevention, Surveillance and Response Team, which identified populations most at-risk for communicable disease such as older adults living in long-term care facilities and children in childcare with high vaccine exemption rates. Other goals were to improve outbreak coordination, surveillance practices, and risk communication with health care and other partners. Beaudrault said that the Central Oregon Outbreak Prevention, Surveillance and Response Team employed a regional infection prevention specialist and a regional epidemiologist to achieve these goals. As a result, the Central Oregon Team was selected in 2019 as a success story case study before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kusuma Madamala offered an overview of a case study of Central Oregon Modernization that was conducted between January 2020 and June 2021. The goal of this case study, she said was to “understand some of the areas that central Oregon was working on to see if it could be replicable in other parts of the state.” During her presentation, Madamala reviewed the methods of the study, which included key informant interviews and document and data review. Her presentation primarily focused on the learning outcomes of the case study and how COVID-19 affected the study. Madamala highlighted the Tri-County Partnership goal, which

was to “Enhance central Oregon’s public health capacity, expertise and coordination to prevent, respond to, analyze, and communicate communicable disease outbreaks, health inequities, and emerging disease threats.” Madamala also mentioned the pre-COVID review from January 2020 to February 2020, which assessed how public health presence can be improved through a variety of actions, such as improving responsiveness by the local public health agency for reportable disease, expanding reach to target populations, improving the quality of services or programs, and enhancing the quality of data systems.

Madamala provided examples of the responsiveness by local public health agencies. The data showed that local public health agency response for reportable disease via interview attempt increased in central Oregon from 2016 and 2019. In 2016, the proportion of cases with first case disease reporting interview attempt in 4 days was roughly 65 percent in Deschutes County, 40 percent in Crook County, and roughly 22 percent in Jefferson County. In 2019, first case interview attempts increased to 94 percent in Deschutes County, 59 percent in Crook County, and roughly 77 percent in Jefferson County. There was also an improvement in two of three case investigations completed in an Oregon Health Authority-designated required timeframe in Central Oregon from 2016 to 2019. For Deschutes County, the number of case investigations completed within the designated timeframe increased from roughly 97 percent in 2016 to roughly 99 percent in 2019. For Crook County, the number of case investigations completed within the designated timeframe decreased from 80 percent in 2016 to roughly 63 percent in 2019. In Jefferson County the number of case investigations completed within the designated timeframe increased from roughly 22 percent to roughly 76 percent.

Next, Madamala identified key areas in which the reach to target populations was successfully expanded. These areas included expanding locations for infection prevention and control training such as long-term care facilities, fire and police departments, shelters, and detention facilities. There was also a targeted outreach approach with the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, which included infection prevention, vaccination outreach events for influenza, development and fostering of relationships with tribal communities, and preparedness drills conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Madamala then described how the Tri-County Partnership improved quality of services or programs. It drafted weekly tri-county influenza surveillance reports during flu season, developed a tri-county flu website, drafted quarterly tri-county communicable disease reports, provided local data to use for training content, drafted “after outbreak action” reports, and developed other web-based information specific to childcare and long-term care facilities.

Speaking about the Tri-County Partnership pre-COVID-19 review, Madamala illustrated how the partnership worked to achieve quality enhancement to data review systems. It established a memorandum of understanding for sharing data from the Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-Based Epidemics (ESSENCE) program; participated in regional training on surveillance data systems that used the Oregon electronic disease surveillance system (known as Orpheus); conducted weekly tri-county (which included the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs) surveillance data check-ins; and implemented data completeness and quality reviews. This prior work affected early COVID-19 response between March 2020 and June 2020 in several ways, Madamala said. Tri-county positions helped build relationships throughout Central Oregon before COVID-19; well-trained staff and preexisting relationships helped direct the response; and the staff needs of community members, such as providing personal protective equipment to long-term care facilities employees.

Madamala also explained the importance of a joint county information center that the Tri-County Workforce launched in early March 2020, which released consistent information about COVID-19 and worked to communicate this information effectively to communities across county lines. Despite each of the three counties having distinct communications and epidemiology reports, these efforts remained consistent in reporting information at the same level of detail and being coordinated with leadership in each county. The joint information center also worked to produce accelerated rapid reports in response to public interest in COVID-19.

Madamala spoke of the challenges encountered by the Central Oregon Tri-County workforce. For example, different counties had different needs in response to the spread of COVID-19. Additionally, these counties experienced difficulties maintaining adequate workforce capacity, even in a region that was well set up for case investigation. This loss of workforce talent from retirement, changing jobs, or leave of absence also contributed to loss of institutional knowledge. Madamala spoke with Tri-County leadership to understand what is required for various health-related positions to be sustainable. She found, that for the Tri-County Regional Epidemiologist position to be sustainable, there must be increased mentorship, administrative and data support, a structured peer community to share and exchange knowledge, competitive compensation, increased workforce capacity on topics beyond communicable disease, and an increase in leadership from state health departments in supporting regional epidemiologists.

In his presentation, Baker described Jefferson County as a rural area with a small health department of only 14 full-time employees, with most services being tied to direct fee for service. This meant, “very little

flexibility with funding and very little staffing capacity to upscale when we need to.” The Tri-County Partnership program allowed the Jefferson County Health Department to increase workforce capacity by hiring appropriate staff, such as an epidemiologist or individuals with advanced nursing skills. Baker reiterated that central Oregon is a very tight-knit community that crosses county boundaries. The Tri-County Partnership made it possible for all three local health departments to work together to build capacity. Jefferson County achieved this goal by accessing nonprofit community-based organizations and other support mechanisms from more urban communities in Deschutes and Crook County that were previously unaware of the unmet need of services that these organizations could provide.

Because of the partnership, Baker said, Jefferson County was able to expand services and service delivery for highly vulnerable populations, which it had previously been unable to achieve. In addition to increasing workforce capacity, Jefferson County was also able to expand its delivery of services to include congregate settings such as the Jefferson County detention center, adult foster care homes, and other settings it previously could not reach prior to the Tri-County Partnership. Baker remarked that the COVID-19 pandemic also highlighted increased vulnerability of these populations and the importance of being able to deliver services to those in need. Furthermore, the Tri-County Partnership allowed the Jefferson County Health Department to hire an “environmental hazards preparedness coordinator.” The coordinator is responsible for examining how extreme weather conditions (e.g., fires, flood, smoke, and severe winter weather) disproportionally impact vulnerable populations in the Tri-County community. Baker said that climate change is still a topic being debated among the Tri-County community, but he added that the Tri-County Partnership has been effective in this debate. “The ability to partner with our neighboring counties to be the lead [in the climate change debate] takes a lot of the stress,” he said, but it also makes it possible to reap “the benefit of that partnership in place and the benefit of having that work done.” The partnership has also helped bypass political considerations that are associated with environmental hazard-related positions, such as the environmental hazards preparedness coordinator. Finally, Baker concluded his remarks by expressing excitement about the potential of future work to be achieved and his gratitude for the partnerships available to the Jefferson County Health Department.

Yeager commented that solving public health workforce recruitment issues “isn’t as simple as posting jobs.” She emphasized that workforce solutions that facilitate meeting needs across communities could be a meaningful solution for other states and localities.

ADDRESSING PUBLIC HEALTH WORKFORCE CHALLENGES: A STATE AGENCY PERSPECTIVE

The next panelist was Nicole Alexander-Scott, an adult and pediatric infectious disease physician public health leader, who previously served as the Director of the Rhode Island Department of Public Health, and as President of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, the national organization for state health directors. Alexander-Scott began her presentation by saying there is a need for a strengthened public health workforce and proposed that solutions to workforce recruitment and retention should be “trauma informed.”

Anyone who joins the public health workforce is “running towards the fire,” Alexander-Scott explained, so there needs to be a support system in-place that recognizes what responsibilities members of the workforce are willing to assume.

This became particularly apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the stresses placed on that workforce led to various traumas. Workers exposed to traumas must be given adequate time to process those traumas and heal, and beside the benefits to existing workers, trauma-informed strategies can be used to attract additional members of the public health workforce.

Alexander-Scott said that approaches to solving public health workforce issues can be categorized in three different areas: First, the current public health workforce requires more than just the governmental public health workforce given the needs (e.g., for workforce capacity building and community engagement) discussed in earlier presentation, and a recognition that all sectors can work to advance public health. Second, the current health care workforce is the sector people are most familiar with and intertwines with the public health workforce to reflect the population health workforce that has been referenced in previous presentations. Third, it is crucial to focus on creating a diverse and competent pipeline. She noted different timelines for engaging a more diverse and competent workforce, starting with education of younger students or of individuals interested in pivoting from one workforce to the public health workforce.

Alexander-Scott shared an experience from Rhode Island: CHWs serve as a prominent workforce that is overlooked or not understood. Some of the efforts Rhode Island has undertaken to “professionalize” CHWs include a certification process that recognizes differences in individual educational attainment or language proficiency. Alexander-Scott said that these individuals “bring a wealth of knowledge and life experience to the public health workforce that is valuable and necessary.” These individuals may serve as health navigators, housing authority professionals, or somebody who is working to create nutritious options

for a community. There should be an approach, Alexander-Scott said, that accounts for the diverse backgrounds of people who join the public health workforce pipeline. The Rhode Island Department of Health partnered with an accreditation board to develop a process for CHWs that recognized the barriers to accessing opportunities such as educational attainment or literacy and language proficiency. This accrediting body partnership looked for creative and simplified ways to allow individuals to apply for community health-oriented jobs while emphasizing experience and the opportunity for gaining additional qualifications. Also, it is important to build a process for supporting individuals from diverse backgrounds into a paid workforce pipeline, which can include gaining CHW accredited certification. Leadership at the Rhode Island Department of Health partners with leading faculty at Rhode Island College to support an accessible accreditation process and joined together to create the Rhode Island Community Health Worker Association. The association serves as a “home base infrastructure for all those interested in this field whether you’re certified or not to become a member and participate in this association for community health workers.” The association also provides the opportunities for continuing education and employment counseling and to advocate for proper compensation and funding for CHWs. The association serves as an entity that promotes the community health workforce as a valued profession and how it contributes to the greater public and population health workforce, deserving quality wages build into the workforce system.

Alexander-Scott noted that having such an association with unified focus creates pathways for bringing people from diverse backgrounds with various lived experiences that are critical into the valued profession of CHWs. This allows for being intentional about continuing education opportunities that may serve as an avenue for more specialized community health work such as behavioral health or HIV care, and for additional licensures (e.g., registered nurse, certified nursing assistant, social worker, or case manager). Strengthening pipeline possibility across the entire workforce spectrum will ultimately benefit population health, and help sustain the positive outcomes needed, with disparities eliminated. Alexander-Scott spoke about two ways to help advance health equity through workforce investments. At the community to clinical interface, people may be most familiar with CHWs, who add tremendous value, for example by conducting home visits to ensure that individuals prescribed asthma medication secure and benefit from it, by addressing environmental exposures, by accessing other life essentials like safe housing, and by supporting access to pharmacy or other ways to avert emergency department utilization. Second, there are nonclinical opportunities for CHWs to connect with the community. The Health Equity Zones Initiative in

Rhode Island mirrors other similar community-led, place-based models throughout the country that offer opportunities for CHWs to make a difference. By investing resources that support what this workforce does for their respective community, CHWs can help advance health equity and are valued professionals to improve the health of communities and importantly address upstream health inequities.

Alexander Scott closed her remarks by saying that the public health workforce must be intentional about how to grow a diverse and competent public health workforce pipeline. Yeager reiterated the importance of making the connections from recruitment to career ladders to thinking about collaborative opportunities across the population health workforce and different entities including clinical and community settings, various agency levels, and governmental public health.

CREATIVE WORKFORCE SOLUTIONS

The next panelist, Renée Branch Canady, described the Michigan Public Health Institute (MPHI) as a “clear and tangible demonstration of governmental innovation” where a state health department partnered with the state legislature to establish a partnership among academic public health, governmental public health, community public health, and health care.

To highlight staffing models that public health institutes can provide, Canady shared employee metrics from MPHI. In March 2020, MPHI employed 402 “affiliate staff” members, who were then deployed to the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). These staff members supported a collaborative partnership with state health department managers to establish a governmental public health workforce. Canady also described how MPHI responded to the need for capacity growth through “surge hiring,” during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. From April 2020 to December 2020, MPHI hired 328 affiliate staff. Among these hired, MPHI achieved 29.57 percent representation of people of color. Branch-Canady applauded this outcome given that residents of color only account for about 14 percent of the population for the state of Michigan. “It is a staggeringly good outcome…communities being able to see themselves in the public health workforce,” she said. These affiliate staff included a broad array of roles including physicians, epidemiologists, nurses, and project managers.

As of December 2021, MPHI hired 629 affiliate roles, 24 percent of whom converted to State of Michigan civil service employees as positions became available. She emphasized this type of model is “innovation by design,” meaning that intentionality is a key component to

recruiting and retaining a successful workforce, especially in the field of public health.

According to Canady there are two other critical factors for building capacity for the MDHHS partners. Canady described the first factor, consultation and partnership, as “hiring a new employee to partner directly and be a part of that staff is the solution. Other times, the solution is pulling in subject matter experts from MPHI who [are not regular members] of the Department’s staff and workforce.” This definition highlighted the differences between consultation and partnership and the importance of choosing the best strategy to achieve a goal. The second factor is contract management and accountability. For example, Canady provided an anecdote on how the MDHHS reached out to MPHI to help execute $20 million in funding for community technical assistance in September 2021 that needed to be expended by the end of the year. After successful implementation of that contract, MPHI received an additional request from the MDHHS to help execute $25 million in funding for distribution of personal protective equipment into the community, also by the end of December 2021. This example demonstrated that effective contract management and accountability is critical for meeting the needs of a community and plays a central role in public health, especially on accelerated timelines.

Canady then spotlighted the role of public health institutes and the crucial role these entities play in “advancing public health structures, systems and outcomes.” Among the National Network of Public Health Institutes, some institutes, such as MPHI, serve as what Canady refers to as “high-capacity institutes.” She explained that these institutes have a proven track record of large-scale abilities to build local capacity in state service areas: implementing public health initiatives of national significance; recruiting and retaining a robust staff of public health subject matter experts; supporting governmental partners; and demonstrating strong financial and business acumen. While the High-Capacity Institutes can achieve all these goals, most other institutes of varying size within the National Network of Public Health Institutes also effectively achieve one or several of the goals. Canady elaborated on how institutes achieve these goals is often aligned with organizational structure. For example, some institutes are affiliated with a university and others may remain in the nonprofit sector.

Canady finished her remarks with what she referred to as “learning lessons” as opposed to “lessons learned” to elicit how ongoing learning is key to addressing gaps in public health workforce capacity. The first lesson she mentioned was “Building Capacity for the Capacity Builders,” which encompasses scaling health equity work and doing so equitably. Canady said, “We have found that a commitment to an inward facing

lens and an externally facing lens have been critically important. Not just ‘what’ do we do as public health, but ‘how’ are we doing?” She continued, asking,

How are we scaling equity work about justice and deconstructing historical consequences of racism, classism, gender discrimination? How are we looking at the onslaught of demands on our profession and scaling that in a way that is equitable, honors our capacity, honors the people that we are serving?

The second lesson Canady proposed was “Walking the Talk.” She emphasized the need for authenticity when it comes to practicing health equity and promoting health equity in action. “If we are tiptoeing around the historical legacy of racism, gender discrimination, classism…we’re not really doing equity,” said Canady.

The third lesson Canady mentioned was “The Tyranny of Turnover” that included the concepts of the Great Resignation and the hidden resignation. The latter refers to the visible exodus from the public health workforce that society observed because of pandemic provoked stress and burnout. However, the hidden resignation describes individuals who have remained in the workforce but have “shut down” because of the same traumas. Canady acknowledged the importance of supporting the remaining workforce to best reduce continuous turnover. The fourth lesson Canady highlighted was “Flipping dominant and bureaucratic narratives.” This lesson encompassed the concepts of “Addressing internal oppression” and “Moving from the view as ‘sluggish/wasteful/inflexible to accountable/disciplined/structured’” as part of lived experiences working in governmental public health. The fifth lesson Canady explained was “Tasks and Tools.” This lesson included the concept of “resisting the natural institutional inclination to conformity.” She elaborated that solutions to shared problems are often distinct across jurisdictions. The sixth lesson highlighted was “Fidelity to Model,” which Canady proposed “when equality becomes the enemy of equity.” She said that issues around equity do not have a “one-size-fits-all” approach and that solutions may vary across state agencies and other public health partnerships. The final lesson Canady exemplified was “Politics vs. political will.” She elaborated that the public health workforce has “seen a hyper-politization of our profession,” which has posed challenges for the public health workforce. However, Canady stressed that attention to political will of and for public health professionals can provide the opportunity for solutions to political polarization and challenges.

Canady ended her presentation with a quote from the Roman philosopher Seneca: “It’s not because things are difficult that we dare not venture. It’s because we dare not venture that they are difficult,”

which implied innovation requires executing creative solutions to meet the 21st century needs of the public health workforce. Yeager noted that the panel highlighted innovations that have been witnessed or implemented during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and underscored the importance of exploring how to apply these innovations in other settings to address the ongoing challenges in public health and population health workforce recruitment and retention.